Enthusiastically, Richard Horton1 reports on the foundation of the Italian Institute of Planetary Health at a time when youth strikes, an emerging pandemic of a new coronavirus, and burning forests remind us of our planet being in jeopardy. We agree that something must change so that the undoubtable advances in science and medicine that were made since the time of Lucretius translate into a better life for all humans, no matter who they are, where they were born, and where they live and work.1 Yet, the lamented crisis of trust in science and medicine cannot be overcome by concepts of global health or planetary health unless their actors truly embrace the planetary concept and approaches. The most pressing challenges are global, and a transnational approach must be the process to reach solutions. If knowledge is to be trusted and translated into action, it must be a joint effort emerging from participatory knowledge generation, which is at the heart of transdisciplinarity.

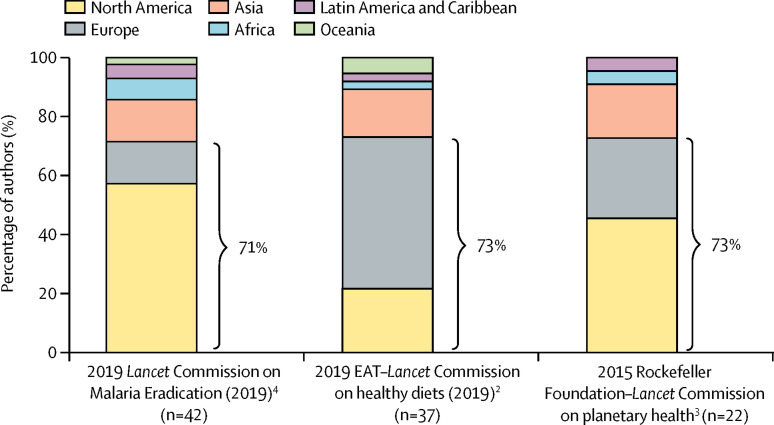

However, in today's reality, whose knowledge really counts and who drives the synthesising and prioritising of knowledge for change? Three recent Lancet global health Commissions are exemplary of a striking imbalance: more than 70% of Commission authors originated from institutions based in North America and Europe, home to less than 20% of the world's population (figure ).2, 3, 4 It is yet another betrayal in a globalised world if those who listen, those who are asked for their opinions, and those who make decisions and provide global guidance, do not adequately reflect the so-called information societies on our planet. The guide for transboundary research partnerships is one initiative aimed at bridging this divide between low-income and middle-income countries on the one hand, and high-income countries on the other, emphasising the importance of mutual trust, mutual learning, and shared ownership.5 At the moment, Africa (represented by only 7% of members of the Lancet Commission on Malaria Eradication4) consumes more of the knowledge produced in high-income countries than vice versa. Building research capacity in low-income and middle-income countries, and fostering transboundary research partnerships, are therefore important steps towards generation and application of more local knowledge.6 Another important move would be for highly respected scientific journals such as The Lancet to promote a more equitable representation of our globalised world in its Commissions and editorial boards because global challenges require global partnership and inclusive decision making. Surely, experts on planetary problems and solutions can be found beyond the prime academic institutions in high-income countries.

Figure.

Institutional affiliations of Lancet Commission authors

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Horton R. Offline: After 2000 years, an answer arrives. Lancet. 2020;395:174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393:447–492. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitmee S, Haines A, Beyrer C. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet. 2015;386:1973–2028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feachem RGA, Chen I, Akbari O. Malaria eradication within a generation: ambitious, achievable, and necessary. Lancet. 2019;394:1056–1112. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stöckli B, Wiesmann U, Lys J-A. 3rd edn. Swiss Commission for Research Partnerships with Developing Countries (KFPE); Bern, Switzerland: 2018. A guide for transboundary research partnerships: 11 principles. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saric J, Blaettler D, Bonfoh B. Leveraging research partnerships to achieve the 2030 agenda: experiences from north–south cooperation. GAIA Ecol Perspect Sci Soc. 2019;28:143–150. [Google Scholar]