Abstract

Cell surface-localized P1 adhesin (aka Antigen I/II or PAc) of the cariogenic bacterium Streptococcus mutans mediates sucrose-independent adhesion to tooth surfaces. Previous studies showed that P1’s C-terminal segment (C123, AgII) is also liberated as a separate polypepeptide, contributes to cellular adhesion, interacts specifically with intact P1 on the cell surface, and forms amyloid fibrils. Identifying how C123 specifically interacts with P1 at the atomic level is essential for understanding related virulence properties of S. mutans. However, with sizes of ~51 kDa and ~185 kDa, respectively, C123 and full-length P1 are too large to achieve high-resolution data for full structural analysis by NMR. Here, we report on biologically relevant interactions of the individual C3 domain with A3VP1, a polypeptide that represents the apical head of P1 as it is projected on the cell surface. Also evaluated are C3’s interaction with C12 and the adhesion-inhibiting monoclonal antibody (MAb) 6–8C. NMR titration experiments with 15N-enriched C3 demonstrate its specific binding to A3VP1. Based on resolved C3 assignments, two binding sites, proximal and distal, are identified. Complementary NMR titration of A3VP1 with a C3/C12 complex suggests that binding of A3VP1 occurs on the distal C3 binding site, while the proximal site is occupied by C12. The MAb 6–8C binding interface to C3 overlaps with that of A3VP1 at the distal site. Together these results identify a specific C3-A3VP1interaction that serves as a foundation for understanding the interaction of C123 with P1 on the bacterial surface and the related biological processes that stem from this interaction.

Keywords: Streptococcus mutans adhesin P1, C3 domain, A3VP1 domain, NMR, quaternary interaction

Graphical Abstract

Using nuclear magnetic resonance, we characterize the intermolecular binding interaction between two discrete domains of the cell-surface localized adhesin P1 of cariogenic Streptococcus mutans. The binding site for the adherence-inhibiting monoclonal antibody 6–8C was also identified demonstrating that it acts by disrupting the functional quaternary structure of this salivary agglutinin (gp340)-binding adhesin. These results provide a structural foundation for understanding biological processes underlying bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation.

1. Introduction

Streptococcus mutans is an acidogenic Gram-positive oral bacterium and major etiologic agent of human dental caries, the most common infectious disease worldwide [1] This organism is well adapted to forming biofilms for survival and persistence within dental plaque. Two mechanisms control S. mutans adhesion to tooth surfaces: sucrose-independent adhesion to components of the salivary pellicle and sucrose-dependent adhesion that further facilitates colonization and biofilm formation on the enamel surface [2–4]. The sucrose-independent adhesin P1 (also known as AgI/II, antigen B, PAc) is a known virulence factor of S. mutans and target of protective immunity [5]. P1 is visible by electron microscopy of thin sections of S. mutans as a fibrillar layer projecting from the cell wall peptidoglycan [6,7]. It interacts with the salivary agglutinin glycoprotein complex, composed predominantly of the scavenger receptor gp340/DMBT1, host cell matrix proteins and other bacteria to adhere the pathogen to tooth surfaces [8–15]. More recent work also highlights the role P1 plays in adhesive interactions and biofilm development, via specific quaternary structure assembly [16] and amyloid formation [17], further contributing to S. mutans virulence properties. Characterizing P1’s quaternary interactions at the molecular level is essential to a more complete understanding of S. mutans pathogenesis, and the rational development of novel therapeutic interventions.

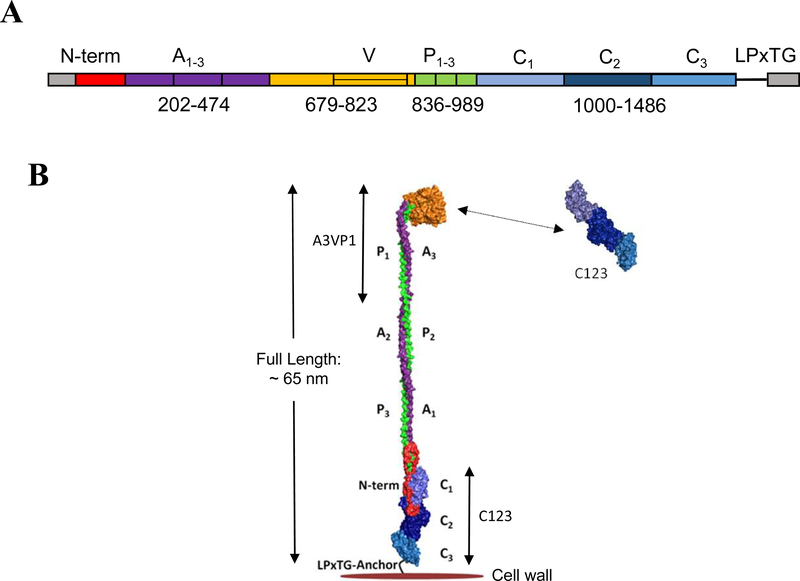

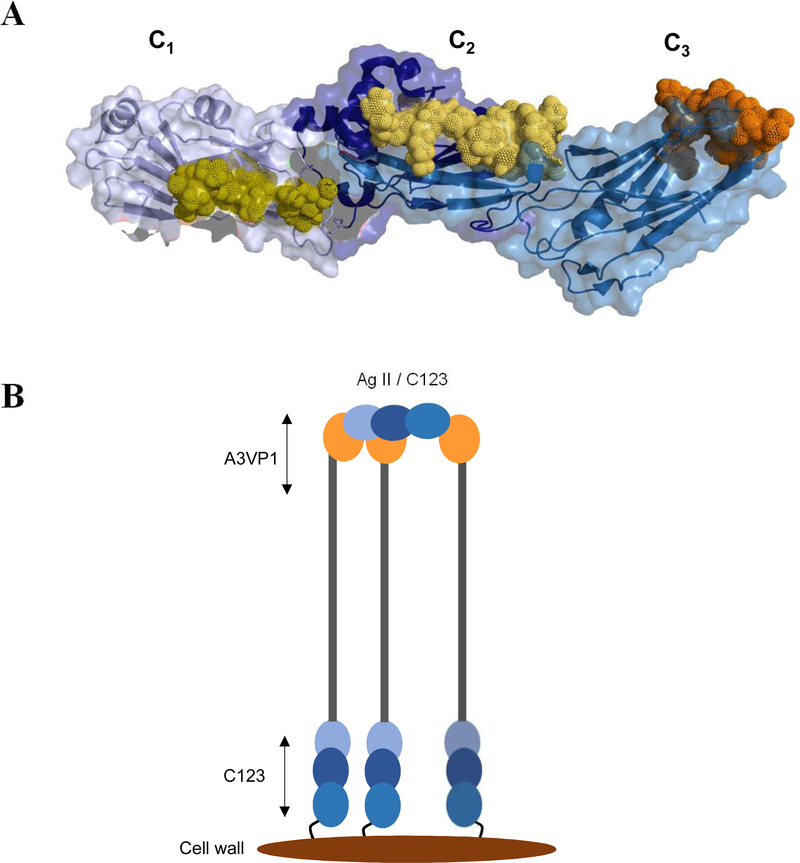

P1 is a large (185 kDa), modular secreted protein which is covalently anchored to the S. mutans cell wall peptidoglycan via the transpeptidase SrtA [5]. It was initially purified from bacterial culture supernatants by column chromatography and identified as a dual antigen (AgI/II), with the Ag II moiety representing the protease-resistant component [10]. P1 consists of a 38-residue secretion signal sequence, an N-terminal region, three alanine-rich repeats (A1–3), a central so-called variable (V) region where most sequence differences among strains are clustered [18], three proline-rich repeats (P1–3), a C-terminal region consisting of three domains (C1–3), and an LPxTG recognition motif for Sortase A, the transpeptidase that cleaves and covalently attaches its substrate proteins, including P1, to the cell wall peptidoglycan [19] (Fig. 1 panel A).

Fig. 1: Schematic representation of S. mutans P1 primary structure and a tertiary model based on existing structural data.

(A) Primary structure of P1 indicating the identified domains serving as the basis for the polypeptides used in this study. (B) Tertiary models of full-length P1 and AgII/C123 based upon x-ray crystal structures of recombinant P1 polypeptides and velocity ultracentrifugation experiments. Model created using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC.

Several X-ray crystal structures of P1 fragments have been resolved, the first being that of the β sheet-rich V-region [20]. Subsequently, the unusual fibrillar structure of the P1 adhesin was recognized when a recombinant polypeptide spanning the third A-region repeat through the first P-region repeat (A3VP1) was crystalized [21]. This crystal structure revealed a high-affinity intramolecular interaction in which the alpha-helix of the A3 repeat intertwined with the polyproline type II helix of the P1 repeat to form an extended hybrid helical stalk to project the globular β super sandwich of the V-region at the apex of the structure.

Next, the crystal structures of a C23 polypeptide [22] and the complete C123 segment were solved [23]. Stabilizing isopeptide bonds were identified within C1, C2, and C3, with each of these three individual domains adopting a DE-variant IgG fold [23]. Electron microscopy and velocity sedimentation experiments of full-length P1 demonstrated a molecular length of ~65nm and suggested a tertiary structure model in which the A3VP1 and C123 segments are physically separated by the extended A/P stalk with the C123 portion of the molecule lying in close proximity to the bacterial cell wall. Lastly, a P1 polypeptide corresponding to the N-terminus through the first A-region repeat (NA1) was co-crystalized with a polypeptide corresponding to the third P-region repeat through the C123 segment (P3C) [24]. Taken together, these combined structural studies enabled a complete tertiary model whereby the N-terminal region wraps around the base of P1’s elongated stalk and also interacts with the C1 and C2 domains to physically lock the structure of the full-length molecule (Fig. 1 panel B).

Despite the elucidation of the entire tertiary structure of P1, its contributions to the adherence and biofilm behavior of S. mutans are still not fully explained. Early Scatchard plot analyses indicated that AgI/II’s interaction with salivary components was complex and involved multiple binding sites, one of which corresponded to AgII [9]. It is now clear that Ag II and C123 are one and the same. Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) that map to different segments of the P1 protein, including to C123, inhibit the binding of S. mutans to immobilized salivary agglutinin (gp340) [12,25]. However, a puzzling finding was that MAbs that bind to C-terminal epitopes did not appear to bind well to S. mutans whole cells, presumably as a consequence of the orientation of P1 on the cell surface in which the C123 domains would be buried near the cell wall [26,27]. This seeming incongruity was clarified when it was discovered that C123 reversibly associates with covalently attached full-length P1 as part of the functional adhesive layer, and that binding of several different anti-P1 MAbs to unfixed cells can trigger C123 release [16]. As part of that study, surface plasmon resonance experiments identified a specific interaction between recombinant purified A3VP1 and C123 polypeptides. It is also now known that functional amyloid formation by S. mutans contributes to biofilm development [17]. P1 is one of the three S. mutans proteins identified thus far that forms amyloid fibrils, with C123 representing the amyloid forming moiety. A sortase-deficient mutant of S. mutans that cannot link substrate proteins, including P1, to the peptidoglycan is defective with respect to biofilm-associated amyloid formation [28]. This suggests that in a biofilm context, S. mutans amyloid fibrillization requires a cell surface-associated nucleation event, similar to other known bacterial amyloid systems [29,30].

Solid state NMR spectroscopy has demonstrated specific binding of heterologously expressed isotopically-labelled C123 to cell wall-anchored P1 [31], most likely via determinants contained within the A3VP1 apical segment. Here, we characterize at amino acid resolution the quaternary interaction of the C3 domain of C123 with the A3VP1 polypeptide to begin to define how the naturally occurring truncation product C123 interacts with full-length P1 on the bacterial cell surface. We also mapped the binding site of MAb 6–8C, an effective inhibitor of S. mutans adhesion, on the C3 domain of P1 thus providing important insight into its molecular mechanism of action. This information is key to understanding the sequence of events for the early stages of bacterial adhesion and subsequent biofilm development, including the formation of functional amyloid. The C3 domain was selected for NMR characterization as this structurally stable, 175-residue construct is more tractable for NMR assignment and characterization than the 519-residue natively-found C123 domain.

2. Results

2.1. Assignment of C3 domain NMR backbone resonances

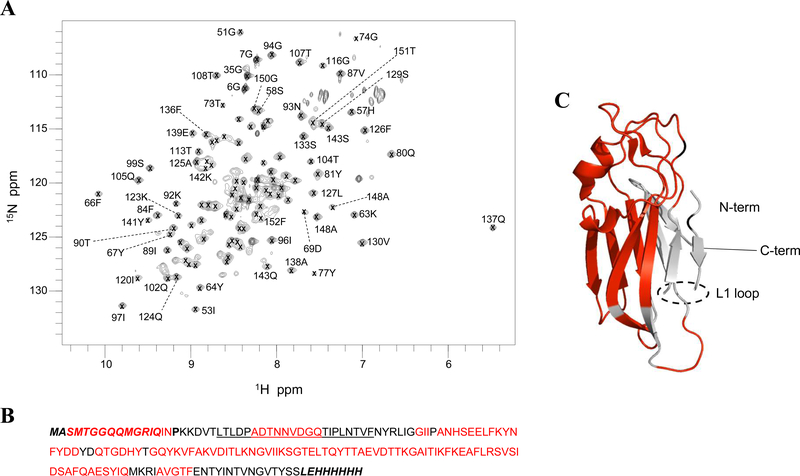

1H-15N HSQC spectra for U-[15N]-C3 indicate that the purified C3 polypeptide is well-folded (Fig. 2). There are 168 resolved NH resonances for the expected 171 amides. Using triple resonance backbone assignment experiments performed on U-[15N, 13C]-C3 samples combined with NOESY-HSQC experiments at pH 5.0, 117 of these resonances, or 68% of the C3 backbone amide protons, were assigned (Fig. 2). These resonances include partial assignment of the L1 loop near the amino terminus of the C3 domain which is unresolved in the X-ray structure for C123 [23].

Fig. 2: NMR assignments of amide resonances in the C3 domain.

(A) 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum at pH 5 and 25 °C. Residue specific assignments for each resonance are marked; 117 of the 175 residues are sequence-specifically assigned with assignments deposited in the BMRB, accession code 27935. (B) The C3 construct used for this work with assigned amino acids indicated in red. A leader sequence at the N-terminus and a C-terminal His-tag which are not native to the C3 sequence in P1 are indicated by italics. The L1 loop, which is unresolved in the C123 X-ray structure, is underlined. (C) Mapping of amide-assigned amino acids (red) onto the C3 domain from the X-ray structure of C123 (PDB 4TSH). Unassigned amino acids are represented in black. Model created using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. All NMR assignment experiments were performed on two independent sample preparations.

2.2. Structure and dynamics of the C3 domain

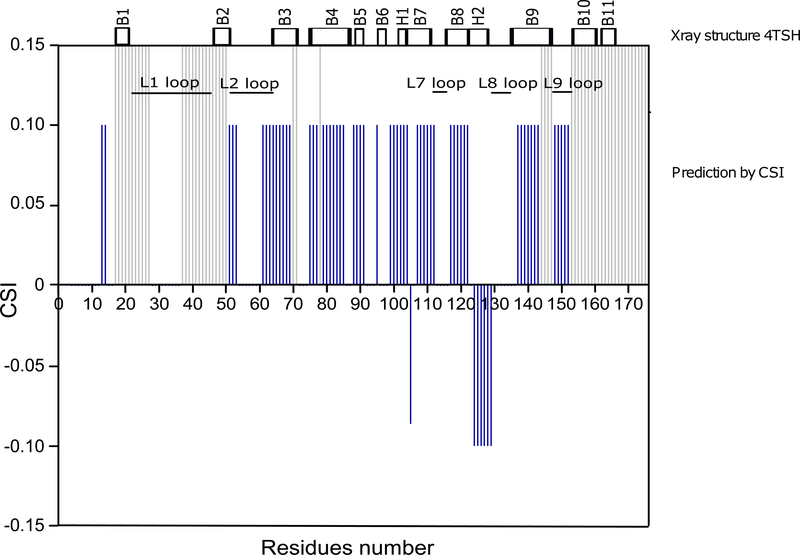

To confirm that the isolated C3 domain retains a structure similar to that within intact C123, we predicted secondary structure elements from 1H, 15N, 13C NMR chemical shifts using the CSI 3.0 web based secondary structure prediction program (http://csi3.wishartlab.com/cgi-bin/index.php) and compared this prediction to the secondary structures observed in the published C123 X-ray crystal structure [23]. As illustrated in Fig. 3, predicted and observed secondary structures are in very good agreement.

Fig. 3: Comparison of secondary structure predictions for C3 using CSI with those observed in the crystal structure for C123[23].

Top. Secondary structure extracted from the published C123 X-ray structure (PDB: 4TSH). Bottom. Chemical Shift Index as a function of C3 residue number. CSI-predicted β-strands, α-helices and loops are represented by values of +1, −1 and 0, respectively. Unassigned C3 residues are represented by light grey bars. All NMR assignment experiments were performed on two independent sample preparations.

To characterize the dynamics of the C3 construct at pH 5 and 6, we measured spin relaxation because it reports on the overall rotational diffusion and local structural fluctuations within the protein. The average R2, R1 and nOe rates measured for the N-terminus, the L1 loop and the rigid beta sheet region of C3 as a function of pH are summarized in Table 1. At these pH values, 15N longitudinal (R1) and transverse relaxation (R2) rates indicate that the C3 construct is mainly rigid with two small regions showing significant dynamics: the N-terminus and the L1 loop. The nOe averages indicate that the N-terminus is highly flexible and unstructured and that the L1 loop exhibits some local dynamics. The dynamics of the L1 loop are in agreement with the absence of electron density for this region in the C123 X-ray structure [23]. The sixteen amino acids at the N-terminus (indicated in Fig. 2, panel B) are part of the construct design for producing recombinant C3 and were not anticipated to be well structured. The remainder of the protein is highly structured and does not exhibit significant dynamics.

Table 1:

Average R2, R1 and nOe relaxation values for the unstructured N-terminus, the flexible L1 loop and the other, rigid, regions of the C3 domain at pH 5 and 6. Details of data analysis can be found in materials and methods.

| R1 (s−1) | R2 (s−1) | nOe | ||||

| pH 5 | pH 6 | pH 5 | pH 6 | pH 5 | pH 6 | |

| N-terminus | 1.12 ± 0.04 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 6.6± 0.6 | −0.18 ± 0.02 | −0.24 ± 0.02 |

| L1 loop | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 1.28 ± 0.02 | 11.9 ± 0.5 | 10.7 ± 1.1 | 0.42 ± 0.10 | 0.30 ± 0.06 |

| Rigid regions | 1.01 ± 0.04 | 1.10 ± 0.09 | 16.4 ± 0.7 | 14.4 ± 1.0 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.78 ± 0.11 |

2.3. The C3 domain interacts specifically with the A3VP1 polypeptide reflecting P1 quaternary assembly

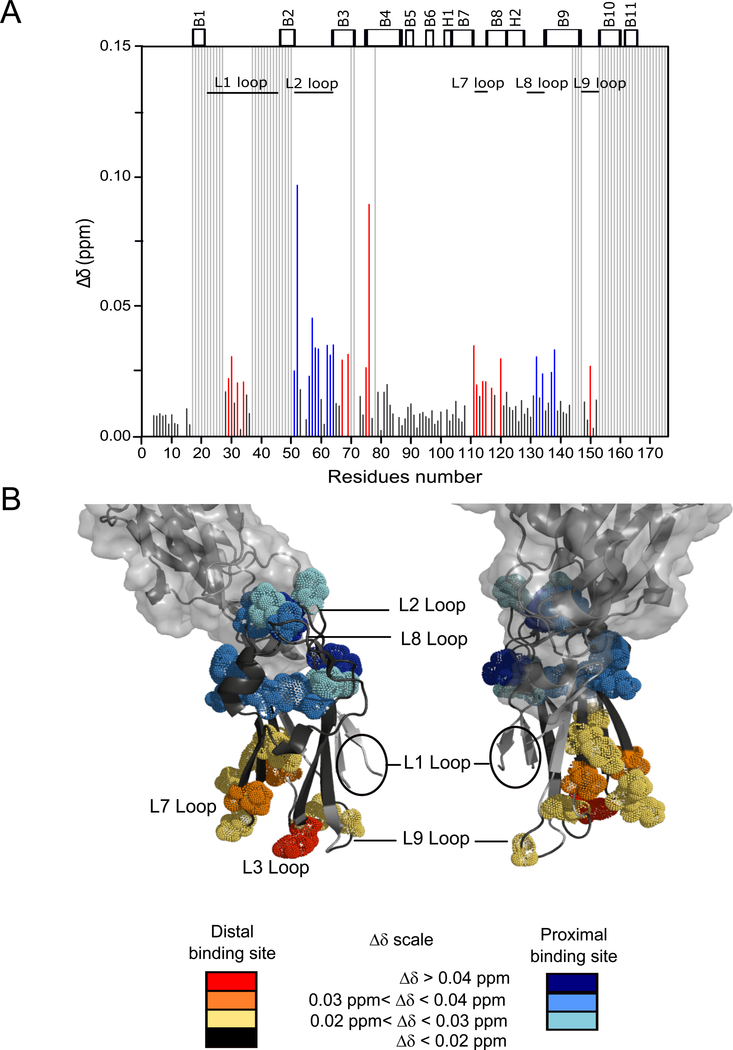

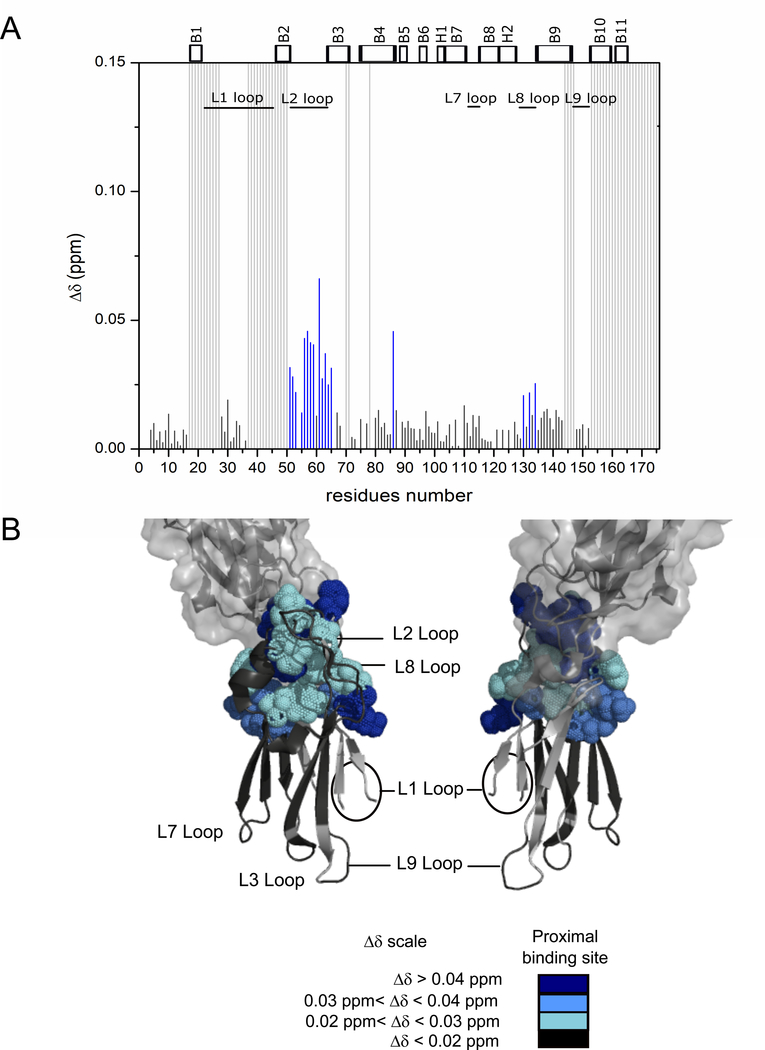

To validate and characterize specific intermolecular interactions between the A3VP1 polypeptide and C3 domain of P1, we recorded chemical shift perturbation experiments using U-[15N]-C3. The successive addition of A3VP1 induced significant chemical shifts changes for particular regions of C3, confirming the specific binding of A3VP1 to C3 (Fig. 4). The C3 domain residues most affected by A3VP1 binding were localized to the L1, L2, L3, L4, L7, L8, and L9 loops. We also observed significant shifts for some residues within the β-sheets directly flanking these loops. Since the β-sheet regions are not solvent accessible, these shifts are likely due to small structural changes stemming from A3VP1 binding to the adjacent loop regions. Mapping of C3 residues affected by A3VP1 binding suggests two A3VP1 binding sites within the C3 structure (Fig. 4). The first binding site, referred to as the proximal binding site, is coincident with C3’s interface with the C2 domain within the intact C123 polypeptide. This binding site is comprised of C3 loops L2, L4, and L8; however, it is unlikely that this binding interface would be accessible to A3VP1 within the context of intact C123. The second binding site, referred to as the distal binding site, is comprised of C3 loops L1, L3, L7, and L9 and would be exposed in intact C123.

Fig. 4: A3VP1 interacts specifically with the isolated C3 domain at two binding sites: proximal and distal.

(A) Chemical shift perturbations, Δδ, for specific C3 amide resonances upon addition of A3VP1 (protein ratios 1:1 C3: A3VP1) at pH 5. Highly perturbed residues at the distal binding site are indicated in red and at residues the proximal binding site are indicated in blue. Minimally perturbed residues are indicated in black and unassigned residues are represented by light grey bars. (B) Mapping of C3 residues perturbed by A3VP1 binding onto the C3 domain from the C123 X-ray structure (4TSH). Spheres indicate the C3 residues that are highly perturbed by interaction with A3VP1. Model created using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. All chemical shift perturbation experiments were performed on three independent sample preparations.

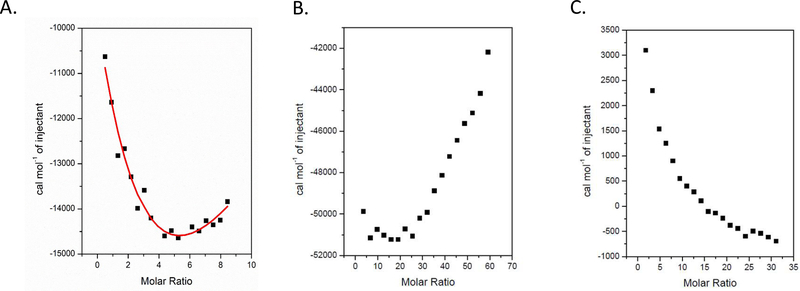

To confirm our interpretation of the NMR data that suggest two binding sites, we analyzed the thermodynamics of A3VP1’s interaction with C3 via isothermal calorimetry (ITC) at pH 5 and 6 (Fig. 5). These experiments were conducted at acidic pH because that is the physiological condition that would be expected in dental plaque containing acidogenic and aciduric S. mutans [1]. The binding isotherms at pH 5 are consistent with two binding sites, one with an intermediate binding constant (KD = 35.2±7.0 μM) and a second with a weaker interaction (KD > 100 μM) that could not be saturated. The isotherms also reveal that the two binding sites are allosteric and that the interaction is pH dependent, with stronger binding at pH 5.

Fig. 5: ITC binding isotherms for C3 binding to A3VP1 at pH 5 and 6.

A) Titration of 3 μM C3 with 124 μM A3VP1 at pH 5. Red line indicates fitting of the data using a two-binding-site model. B) Titration of 1 μM C3 with 300 μM A3VP1 at pH 5. C) Titration of 2 μM C3 with 300 μM A3VP1 at pH 6. All ITC experiments were performed on three independent sample preparations.

2.4. Dynamics of P1’s C3 domain upon binding to A3VP1

Binding of A3VP1 to the isolated C3 domain did not affect the C3 dynamics as 15N longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rates as well as nOe averages collected for the C3/A3VP1 complex were similar to those of the C3 domain alone (Table 2). The L1 loop remained dynamic despite A3VP1 binding. This observation is consistent with a weak, transient interaction and the micromolar affinity determined by ITC.

Table 2:

Average R2, R1 and nOe relaxation values for the unstructured N-terminus, the flexible L1 loop and the other, rigid, regions of the C3 domain when in complex with the A3VP1 domain (1:1 C3:A3VP1) at pH 5. Details of data analysis can be found in materials and methods.

| R1 (s−1) | R2 (s−1) | nOe | |

| N-terminus | 1. 20 ± 0.04 | 7.11 ± 0.75 | −0.13 ± 0.01 |

| L1 loop | 1.34 ± 0.06 | 12.24 ± 0.95 | 0.45 ± 0.12 |

| Rigid regions | 1.43 ± 0.05 | 17.09 ± 0.89 | 0.83 ± 0.11 |

2.5. Interactions of P1’s C3 domain with A3VP1 and with P1’s C12 domains

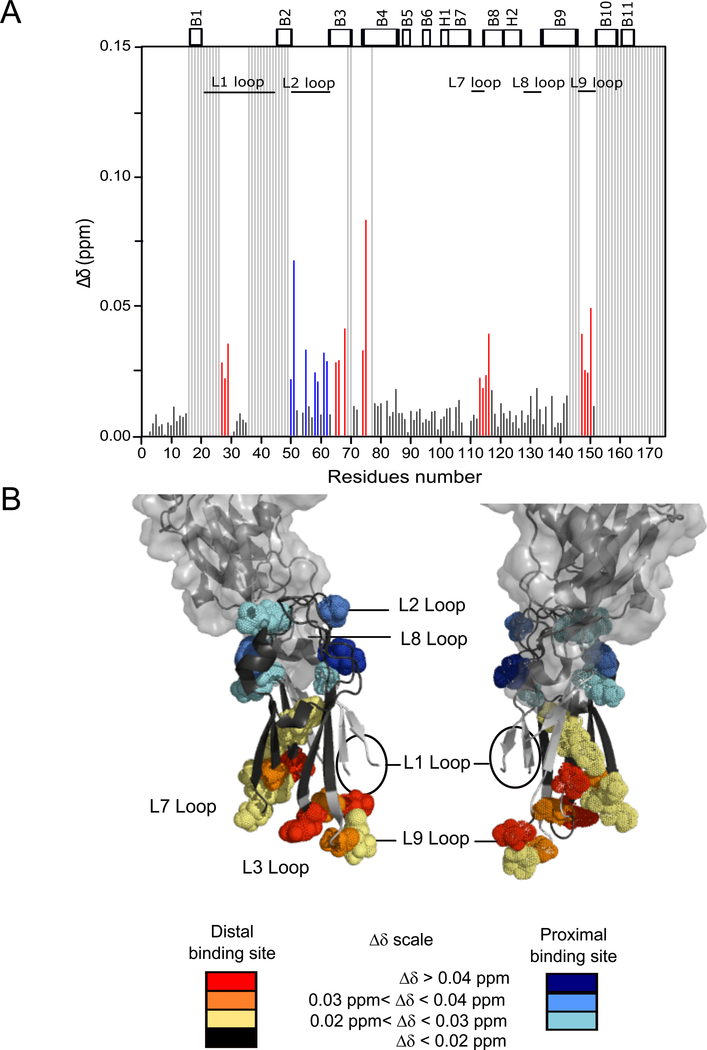

The C123 product (AgII) of S. mutans P1 is naturally occurring and would thereby be present within dental plaque in the human mouth, while the isolated C3 domain is an artificial construct utilized in our studies for practicality. In order to mimic the biological context in which the C123 truncation product would associate with full-length P1 on the S. mutans cell surface, and to identify the A3VP1 binding site on C3 when the C12 domains are also present, we recorded NMR titration experiments whereby the purified C12 polypeptide was added to the C3 domain with subsequent addition of A3VP1 to the C12/C3 complex. The C3 residues affected by interaction with C12 are located on the C3 L2, L4 and L8 loops, confirming the C2/C3 interface observed in C123’s X-ray structure [23] (Fig. 6). Addition of A3VP1 to the C12/C3 complex induced significant chemical shift perturbations in the L1, L3, L7, L9 loops, as well as some further shifts in the L2 loop of C3 (Fig. 7). This suggests that biologically relevant binding of A3VP1 corresponds to the distal binding site of C3 that we identified, and that the proximal binding site is an artefact of characterizing C3/A3VP1 interactions in the absence of C12. The further shifts within C3’s L2 loop indicate that A3VP1 is able to compete with C12 binding at the proximal site. However, this interaction is physiologically irrelevant as it would not occur in the context of the natural P1 truncation product C123, in which C12 is covalently attached to C3 thereby obscuring this potential A3VP1 binding interface.

Fig. 6: Interaction of C12 with the proximal binding site of C3.

(A) Chemical shift perturbations, Δδ, for specific C3 amide resonances upon addition of C12 (protein ratios 1:1 C3:C12) at pH 5. Highly perturbed residues at the proximal binding site are indicated in blue. Minimally perturbed residues are indicated in black and unassigned residues are represented by light grey bars. (B) Mapping of C3 residues perturbed by C12 binding onto the C3 domain from the C123 X-ray structure (4TSH). Spheres indicate the C3 residues that are highly perturbed by interaction with C12. Model created using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. All chemical shift perturbation experiments were performed on three independent sample preparations.

Fig. 7: Interaction of A3VP1 with the C3 domain upon reconstitution of the C123 complex.

(A) Chemical shift perturbations, Δδ, for specific C3 amide resonances upon addition of A3VP1 after C3 is complexed with C12 (protein ratios 1:1:2 C3:C12:A3VP1) at pH 5. Highly perturbed residues at the distal binding site of C3 are indicated in red and at the proximal binding site are indicated in blue. Minimally perturbed residues are indicated in black and unassigned residues are represented by light grey bars. (B) Mapping of C3 residues perturbed by A3VP1 binding when C3 in complex with C12 onto the C3 domain from the C123 X-ray structure (4TSH). Spheres indicate the C3 residues that are highly perturbed by interaction with A3VP1. Model created using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. All chemical shift perturbation experiments were performed on three independent sample preparations.

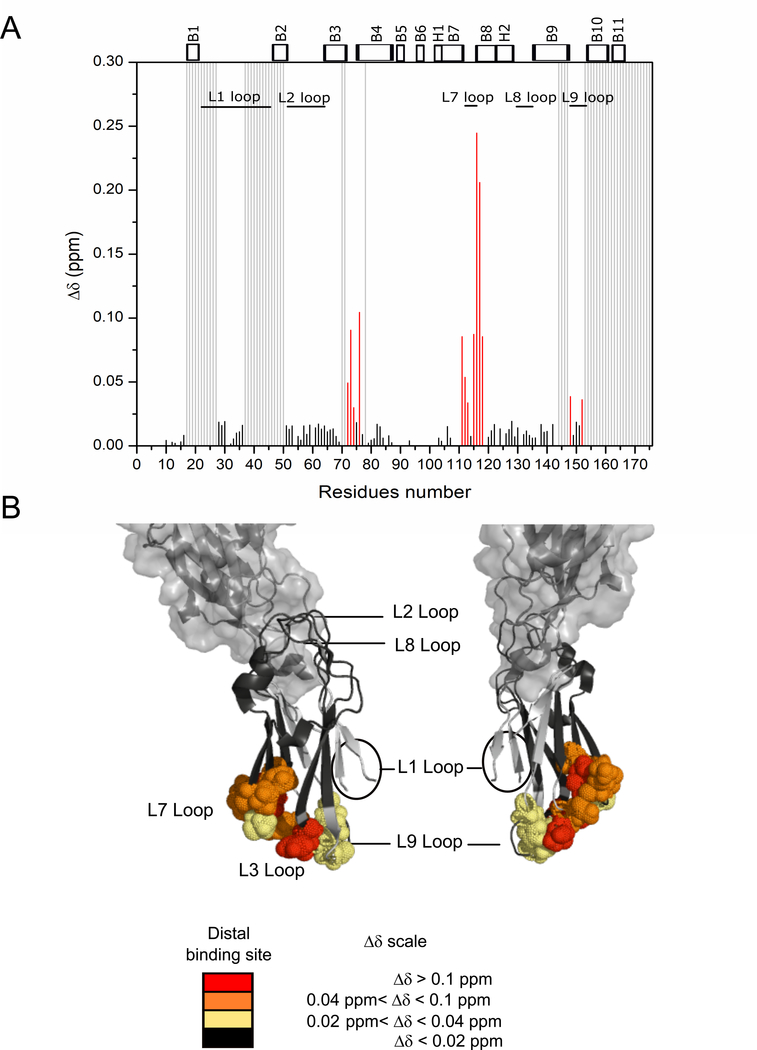

2.6. Characterization of monoclonal antibody 6–8C’s interaction with the C3 domain of P1

Anti-P1 monoclonal antibodies that can effectively inhibit adherence of S. mutans to salivary agglutinin include 1–6F, 4–10A, and 6–8C [23], and have been mapped to the apical head, extended stalk, and C123 segments of P1, respectively [16]. While 6–8C’s reactivity with the C-terminus of purified P1 had been determined previously, it appeared poorly reactive with whole cells [25]. It was not until S. mutans cells were treated with glutaraldehyde that the apparently transient quaternary interaction between C123 and S. mutans cells was preserved and the ability of MAb 6–8C to inhibit S. mutans adherence by liberating a reversibly bound adhesive moiety was explained [16]. These findings suggested that the quaternary interaction of C123 with P1 on the surface of S. mutans cells is critical for bacterial adhesion to gp340 within the acquired salivary pellicle, but molecular level details regarding the concerted interactions of C123 with cell surface-localized P1 and an adherence-inhibiting mAb are lacking. Here, we performed NMR titration measurements of mAb 6–8C binding to the C3 domain in order to identify its specific binding site. The addition of 6–8C to U- [15N]-C3 shows significant chemical shift perturbations confirming a specific and direct interaction of 6–8C with the C3 domain (Fig. 8). We note the average shift for residues affected by 6–8C binding (0.088 ppm) is higher than the average shift for those affected by A3VP1 binding (0.032 ppm), suggesting a stronger interaction of 6–8C with the C3 domain. The C3 residues most affected by 6–8C addition are localized in the L3, L7 loops and B7 and B8 β-sheets (Fig. 8). Notably, the 6–8C binding site is in close proximity to the distal, and relevant, binding site of C3 with A3VP1, although it does not fully overlap with it (Fig. 8). These findings help to explain the observation that glutaraldehyde fixation of the C123 to P1 on intact S. mutans cells preserves 6–8C reactivity [16], and suggest that the ability of this mAb to inhibit S. mutans adherence stems from interference with the C123-A3VP1 interaction.

Fig. 8: The murine monoclonal antibody 6–8C binds near the A3VP1 distal binding site on C3.

A) Chemical shift perturbations, Δδ, for specific C3 amide resonances upon addition of 6–8C (protein ratios 1:0.44 C3:MAb 6–8C) at pH 5. Highly perturbed residues overlapping with the distal binding site are indicated in red. Minimally perturbed residues are indicated in black and unassigned residues are represented by light grey bars. B) Mapping of C3 residues perturbed by 6–8C binding onto the C3 domain from the C123 X-ray structure (4TSH). Spheres indicate the C3 residues that are highly perturbed by interaction with MAb 6–8C. Model created using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. All chemical shift perturbation experiments were performed on three independent sample preparations.

3. Discussion

Previous work had demonstrated the ability of the C123 truncation fragment (aka AgII) of S. mutans P1 to interact with covalently attached full-length P1 (aka Ag I/II) on the bacterial cell surface [16,31], to adhere to salivary agglutinin [23], and to form amyloid fibrils within biofilms [17]. However, previous experiments lacked sufficient resolution to characterize the molecular nature of the C123 interaction with other P1 polypeptides. In this study, we follow-up on our solid-state NMR demonstration that C123 binds specifically to cell wall-associated P1 [31], and that C123 and A3VP1 demonstrate a specific concentration-dependent interaction by surface plasmon resonance [16]. We used solution NMR to identify residues within C123 that contribute to this critical binding interaction. We began with a single domain of C123 of tractable size for solution NMR characterization. C3 is a folded, stable, protease-resistant domain that retains an ability to interact with A3VP1. We continued to utilize the A3VP1 polypeptide in the current study because it represents that portion of P1 that projects from the cell surface and contains the adhesin’s apical head in the context of the stabilizing hybrid helical stalk [21].

Our NMR and ITC experiments establish a specific interaction of A3VP1 with the C3 domain. S. mutans ferments dietary sugars to produce acid, and thrives within the resultant acid environment thus outcompeting less acid tolerant oral bacteria [32]. Therefore, we conducted our experiments in a pH range that would be encountered in acidified dental plaque. The two binding sites that we identified within C3 were dubbed proximal and distal, with the distal binding site considered as the relevant interface with A3VP1. In contrast, we do not consider the proximal A3VP1 binding site within the C3 domain to be reflective of physiological conditions because that site would be occupied by C12 covalently linked to C3 as part of the C123 moiety produced naturally by S. mutans. Using ITC we determined that the two binding sites are allosteric. Moreover, the ITC titration profiles at pH 5 and 6 indicate that the A3VP1-C3 interaction is pH dependent. At pH 5, one of the two binding sites was saturated, with an affinity constant of 35.2±7.0 μM, while at pH 6 neither site was saturable. The stronger A3VP1-C3 interaction at pH 5 suggests that binding is stabilized by both electrostatic and hydrophobic forces, and would therefore be strengthened within acidified dental plaque. The proximal A3VP1 binding site on C3 is chiefly hydrophobic with only three ionizable residues: His 57, Ser 58, and Glu 59. In contrast, the relevant distal binding site demonstrates considerably more ionizable residues: Thr 30; Asn 32; Asp 34; His 76; Thr 112; and Lys 114. Most notably, the histidine residues would be most susceptible to ionization in the pH 5–6 range. Accordingly, the His 76 residue of C3 shows a significantly larger chemical shift perturbation relative to other residues upon binding to A3VP1.

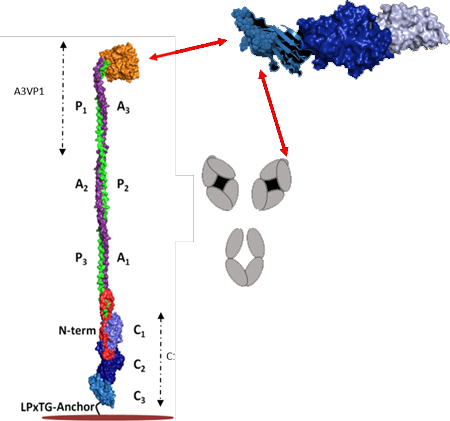

The affinity constants (KD) for A3VP1-C3 interactions were challenging to estimate due to an inability to fully saturate both binding sites. This suggests a low residence time for A3VP1 binding to isolated C3. These data are consistent with a rapid dissociation of the A3VP1-C3 complex, and low affinity between A3VP1 and the individual C3 domain. The presence of additional A3VP1 binding sites within the C1 and/or C2 domains remains to be determined, and may contribute to a higher avidity multivalent interaction of C123 with cell surface-localized P1 where multiple molecules would be available for binding. Indeed, the fibrillar P1 layer visualized by electron microscopy of thin sections of S. mutans appears to be tufted rather than uniform [6,7], and is therefore consistent with a model in which several cell wall bound P1 molecules bind simultaneously to multiple sites on C123 that gathers them together into clusters. To test this model, we aligned the C1, C2, and C3 structural folds and identified regions in C1 and C2 which correspond to the distal binding site for A3VP1 on C3 (Fig. 9 panel A). We note all three putative binding sites are surface exposed in C123 and decorate the surface in a way that would enable C123 to interact with up to three copies of P1 on the cell surface (Fig. 9 panel B). This model will be tested in our future work and is consistent with both electron microscopy studies as well as epitope mapping for Mab 6–8C (Brady, unpublished).

Fig. 9: Working model for binding of salivary AgII/C123 to P1 on the S. mutans cell surface.

(A) Possible interaction sites of A3VP1 with the individual domains in the C123 polypeptide identified by a structural alignments of C3 with C1 and C2 to identify regions in C1 and C2 corresponding to the A3VP1 distal binding site of C3. The C3 distal binding site consisting of the L3, L7, and L9 loops is represented in orange sphere whereas the structural homologues of this binding site are shown in light yellow for the C2 domain and in gold for the C1 domain. Model created using PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.0 Schrödinger, LLC. (B) Working model of C123 binding to intact Adhesin P1 on the S. mutans surface based on this study and electron microscopy observations [6,7].

The interaction of C3 with the anti-P1 mAb 6–8C was studied in order to better understand the mechanism of inhibition of S. mutans adherence to salivary agglutinin by this antibody [12]. While neutralizing antibodies often act by directly blocking an adhesive interaction, Heim et al. observed that the adhesive fragment C123 was released from S. mutans cells in the presence of 6–8C [16]. This suggested that 6–8C may not directly interfere with C123’s established interaction with salivary agglutinin [23], but instead might act indirectly by triggering the release of adhesive C123 fragments from the bacterial cell surface. The 6–8C antibody is reactive with polypeptides corresponding to C123, C12, C23, C2, and C3 suggesting that it recognizes an epitope repeated in at least two, if not all 3 domains (Brady, unpublished). Thus far we have been unable to purifiy a stable polypeptide corresponding to C1; therefore 6–8C’s reactivity with C1 alone has not been tested. Our NMR data reveal 6–8C’s direct interaction with the C3 domain where it binds to residues located on the L3, L7 loops and β7 and β8 β-sheets overlapping with the distal binding site for A3VP1. The 6–8C interaction with C3 could therefore induce its release from A3VP1 at the identified distal binding site. The interaction of C123 with salivary agglutinin was previously localized to C12, and not C3, via surface plasmon resonance [23] further strengthening the argument that 6–8C does not act by directly blocking the C123-salivary agglutinin interaction. These findings have important implications for potential therapeutic approaches in that disruption of P1’s quaternary structure may be an effective alternative to targeting P1’s direct interaction with its salivary substrate. If additional binding sites for A3VP1 are identified within the C1 and/or C2 domains in the future, these too would likely be disrupted by mAb 6–8C as the interaction of the entire C123 polypeptide with S. mutans cells was disrupted by this antibody [16].

C123 has also been identified as the amyloid forming moiety of S. mutans P1 [17]. S. mutans mutants lacking the spaP gene that encodes P1 lose sensitivity to biofilm inhibition by known inhibitors of amyloid fibrillization suggesting a specific contributory role for P1 amyloid formation during biofilm development. A sortase mutant of S. mutans cannot link P1 or another amyloidogenic protein, WapA, to the cell wall although the proteins are made and secreted extracellularly. The lack of amyloid formation by the sortase mutant suggests that covalent attachment of scaffolding molecules to the cell surface is a necessary step for subsequent amyloid fibrillization [28]. WapA is also a sucrose-independent adhesin of S. mutans whose truncated form (AgA) is amyloidogenic [17]. The cell surface-localized Bap adhesin of Staphylococcus aureus is also processed to an amyloidogenic derivative that aggregates to build the biofilm matrix [33]. Thus a new paradigm is emerging in which dual function proteins serve not only as adhesins, but also participate in a process whereby truncation derivatives build on a scaffolding layer to aggregate in response to environmental cues [33–35]. The interaction of C123 with the A3VP1 segment of cell surface-linked P1 therefore also likely contributes to the formation of amyloid fibrils within S. mutans biofilms. In this study, we focused on characterizing the specific interaction of C3 with A3VP1 as a reflection of the higher order quaternary interaction of C123 with cell wall-linked P1. In the future, we propose to extend this characterization to identifying the binding site for C3 on the A3VP1 surface, to evaluate potential interactions of C1 and/or C2 with A3VP1, and to construct a structural model of the entire A3VP1-C123 complex. Moreover, our current data regarding the C3 domain serve as foundation for characterizing intermolecular interactions relevant to biofilm-related processes such as amyloid formation by C123.

4. Material and methods

4.1. Expression and purification of C3, C12, A3VP1 domains from P1 and mAb 6–8C:

The gene sequences encoding the C3 and C12 domains of P1 were subcloned into the pET23d vector, with a C-terminal His6 tag to facilitate protein purification, as described previously [23]. The fusion proteins were expressed in BL21 (DE3) Escherichia coli cells. For this paper, we produced proteins with natural abundance isotopes, using Terrific broth, and/or uniformly enriched, U-[15N] and U-[15N, 13C], using isotopically enriched M9 minimal media. To increase the yield of recombinant proteins recovered with E. coli cells grown in minimal media, we used a protocol proposed by Marley and his collaborators [36]. Briefly, cells were first grown in Terrific broth supplemented with 100 mg/mL−1 ampicillin at 37 °C (we typically used three 1-L cultures) until OD600=0.8. These cells were collected by centrifugation at 4000 g and 4 °C for 30 min. Cell pellets (from the initial 3-L culture) were resuspended in 60 mL of minimal M9 medium, centrifuged a second time at 4000 g and 4 °C for 20 min and finally resuspended in 1 L of M9 medium containing 100 mg/mL ampicillin, 15N-enriched ammonium chloride and/or 13C-enriched glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). This new culture was incubated for 1 hr at 37 °C before inducing protein expression by addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside. After incubation overnight at 22 °C, cells were centrifuged at 6000 g at 4 °C for 30 min and stored at −80 °C before the purification step.

C12 and C3 were purified using a derived protocol from that described by Tang and collaborators [31]. The cell pellets were resuspended in 30 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and lysed with a microfluidizer; cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14000 g at 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant containing the soluble C12 or C3 was purified using a HisTRAP HP column (GE Healthcare), followed by size exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 200gp column with 50 mM phosphate/100mM NaCl, pH 6.0. Protein purity was verified by the observation of a single and intense band at the expected molecular weight on an overloaded SDS-PAGE gel.

The A3VP1 (386–864) domain was expressed and purified as described previously [21]. Murine ascites fluid served as the source of the previously described mAb, 6–8C [6]. The primary sequence of the constructs we used in this paper are summarized in the Table 3.

Table 3:

Primary sequences for the P1 polypeptides used in this study.

| Constructs | Primary sequence |

| C3 | MASMTGGQQMGRIQINPKKDVTLTLDPADTNNVDGQTIPLNTVFNYRLI GGIIPANHSEELFKYNFYDDYDQTGDHYTGQYKVFAKVDITLKNGVIIKS GTELTQYTTAEVDTTKGAITIKFKEAFLRSVSIDSAFQAESYIQMKRIAVG TFENTYINTVNGVTYSSLEHHHHHH |

| C12 | MASMTGGQQMGRIHFHYFKLAVQPQVNKEIRNNNDINIDRTLVAKQSVV KFQLKTADLPAGRDETTSFVLVDPLPSGYQFNPEATKAASPGFDVTYDN ATNTVTFKATAATLATFNADLTKSVATIYPTVVGQVLNDGATYKNNFTL TVNDAYGIKSNVVRVTTPGKPNDPDNPNNNYIKPTKVNKNENGVVIDGK TVLAGSTNYYELTWDLDQYKNDRSSADTIQKGFYYVDDYPEEALELRQ DLVKITDANGNEVTGVSVDNYTNLEAAPQEIRDVLSKAGIRPKGAFQIFR ADNPREFYDTYVKTGIDLKIVSPMETVVKKQMETGQTGGSYENQAYQID FGNGYASNIVINNVPKLEHHHHHH |

| A3VP1 | [21] |

4.2. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

ITC experiments were performed in buffers composed of 10 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl, pH 5, and 50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, pH 6, at 25°C using a MicroCal ITC200 calorimeter (Malvern). The A3VP1 purified polypeptide (in the syringe) was titrated into purified C3 (in the cell). The titration sequence included a single 0.4 μL injection followed by 20 injections of 2 μL each, with a spacing of 400 seconds between the injections. The starting volume in the cell was 300 μL. The protein concentrations were as follows: 124 μM A3VP1 into 3 μM C3 (pH 5); 300 μM A3VP1 into 1 μM C3 (pH 5); 300 μM A3VP1 into 2 μM C3 (pH 6). OriginLab software (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).) was used to fit the raw data to a two-sequential-binding-sites model.

4.3. NMR experiments

The ensemble of NMR experiments was acquired at 25 °C and NMR samples were exchanged into a buffer containing 10 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl for measurements at pH 5 or into a buffer containing 50 mM phosphate, 100 mM NaCl for measurements at pH 6; buffers contained 10% D2O and 0.02% (w/v) NaN3. Assignment, titration, and spin-relaxation experiments were carried out on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance II spectrometer equipped with a 5mm z-gradient TCI (H/C/N) cryoprobe. All NMR data were processed using TOPSPIN and analyzed with CCPNMR software (http://www.ccpn.ac.uk).

4.4. C3 amide NMR resonance assignments

Purified C3 was characterized at pH 6.0 and pH 5.0 at a protein concentration of 500–800 μM. Backbone resonance assignments were made using standard triple resonance experiments: HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HNCACB and HN (CO)CACB. C3 resonance assignments are deposited in the BMRB, accession code 27935.

4.5. Chemical shift perturbation measurements

Interaction surfaces on U-[15N]-C3 were characterized by chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) measured using a series of 1H-15N-HSQC experiments recorded with increasing volumes of concentrated stocks of ligand candidates: A3VP1, C12 or mAb 6–8C. NMR data were processed using TOPSPIN and analyzed using CCPNMR software. The spectral perturbations were quantified as the combined amide CSPs:

where ΔδH and ΔδN are the changes in chemical shift in the 1H and 15N dimensions, respectively. The change in 15N chemical shift is scaled in calculating the combined CSP to reflect the different chemical shift ranges observed for amide 15N resonances (26.0 ppm) compared to the amide 1H resonances (5.2 ppm) in protein HSQC measurements.

4.6. NMR relaxation measurements

Relaxation measurements, including 15N longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rates as well as 15N‐1H cross‐relaxation rates via steady-state 15N{1H}NOE experiments were performed. For the R1 measurements, longitudinal relaxation delays of 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 400, 512, 800, 1024, 1536, and 2048 ms were utilized with a recycle delay of 3 s. The R2 CPMG measurements were performed with transverse relaxation periods of 17, 34, 51, 119, 170, and 237 ms with a relaxation delay of 3 s. R1 and R2 relaxation curves were to an exponential function [I = A exp(−Rt)], and the errors were measured using the covariance error method within CCPNMR. The 15N{1H} NOE values obtained from ratios of cross-peak intensities in spectra with and without saturation. The relaxation delay was set to five seconds in order to allow the bulk water magnetization to return to near its equilibrium value. The error (σNOE) was determined using the following equation:

where, Isat and Iunsat represent the measured intensities of a particular resonance in the presence and absence of proton saturation, and σsat and σunsat represent the RMS variation in the noise in empty spectral regions of the spectra with and without proton saturation.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by NIH R01 DR021789 to LJB and JRL. A portion of this work was performed in the McKnight Brain Institute at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory’s AMRIS Facility, which is supported by National Science Foundation Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1644779 and the State of Florida. MAM was supported by NIH R21 AI126583.

Abbreviations:

- CSI

Chemical Shift Index

- MAb

Monoclonal antibody

- ITC

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

- Δδ

Chemical shift perturbation

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

Database: BMRB submission code: 27935

References:

- 1.Lemos JA, Palmer SR, Zeng L, Wen ZT, Kajfasz JK, Freires IA, Abranches J & Brady LJ (2019) The Biology of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Spectr 7, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nobbs AH, Lamont RJ & Jenkinson HF (2009) Streptococcus adherence and colonization. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR 73, 407–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolas GG & Lavoie MC (2011) [Streptococcus mutans and oral streptococci in dental plaque]. Can. J. Microbiol 57, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abranches J, Zeng L, Kajfasz J, Palmer S, Chakraborty B, Wen Z, Richards V, Brady L & Lemos J (2018) Biology of Oral Streptococci. Microbiol. Spectr 6, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady LJ, Maddocks SE, Larson MR, Forsgren N, Persson K, Deivanayagam CC & Jenkinson HF (2010) The changing faces of Streptococcus antigen I/II polypeptide family adhesins. Mol. Microbiol 77, 276–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayakawa GY, Boushell LW, Crowley PJ, Erdos GW, McArthur WP & Bleiweis AS (1987) Isolation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for antigen P1, a major surface protein of mutans streptococci. Infect. Immun 55, 2759–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee SF, Progulske-Fox A, Erdos GW, Piacentini DA, Ayakawa GY, Crowley PJ & Bleiweis AS (1989) Construction and characterization of isogenic mutants of Streptococcus mutans deficient in major surface protein antigen P1 (I/II). Infect. Immun 57, 3306–3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleiweis AS, Oyston PC & Brady LJ (1992) Molecular, immunological and functional characterization of the major surface adhesin of Streptococcus mutans. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol 327, 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hajishengallis G, Koga T & Russell MW (1994) Affinity and specificity of the interactions between Streptococcus mutans antigen I/II and salivary components. J. Dent. Res 73, 1493–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell MW, Bergmeier LA, Zanders ED & Lehner T (1980) Protein antigens of Streptococcus mutans: purification and properties of a double antigen and its protease-resistant component. Infect. Immun 28, 486–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell MW & Mansson-Rahemtulla B (1989) Interaction between surface protein antigens of Streptococcus mutans and human salivary components. Oral Microbiol. Immunol 4, 106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brady LJ, Piacentini DA, Crowley PJ, Oyston PC & Bleiweis AS (1992) Differentiation of salivary agglutinin-mediated adherence and aggregation of mutans streptococci by use of monoclonal antibodies against the major surface adhesin P1. Infect. Immun 60, 1008–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purushotham S & Deivanayagam C (2014) The calcium-induced conformation and glycosylation of scavenger-rich cysteine repeat (SRCR) domains of glycoprotein 340 influence the high affinity interaction with antigen I/II homologs. J. Biol. Chem 289, 21877–21887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kishimoto E, Hay DI & Gibbons RJ (1989) A human salivary protein which promotes adhesion of Streptococcus mutans serotype c strains to hydroxyapatite. Infect. Immun 57, 3702–3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bikker FJ, Ligtenberg AJM, Nazmi K, Veerman ECI, van’t Hof W, Bolscher JGM, Poustka A, Nieuw Amerongen AV & Mollenhauer J (2002) Identification of the bacteria-binding peptide domain on salivary agglutinin (gp-340/DMBT1), a member of the scavenger receptor cysteine-rich superfamily. J. Biol. Chem 277, 32109–32115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heim KP, Sullan RMA, Crowley PJ, El-Kirat-Chatel S, Beaussart A, Tang W, Besingi R, Dufrene YF & Brady LJ (2015) Identification of a Supramolecular Functional Architecture of Streptococcus mutans Adhesin P1 on the Bacterial Cell Surface. J. Biol. Chem 290, 9002–9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Besingi RN, Wenderska IB, Senadheera DB, Cvitkovitch DG, Long JR, Wen ZT & Brady LJ (2017) Functional amyloids in Streptococcus mutans, their use as targets of biofilm inhibition and initial characterization of SMU_63c. Microbiology 163, 488–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brady LJ, Crowley PJ, Ma JK, Kelly C, Lee SF, Lehner T & Bleiweis AS (1991) Restriction fragment length polymorphisms and sequence variation within the spaP gene of Streptococcus mutans serotype c isolates. Infect. Immun 59, 1803–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly C, Evans P, Ma JK, Bergmeier LA, Taylor W, Brady LJ, Lee SF, Bleiweis AS & Lehner T (1990) Sequencing and characterization of the 185 kDa cell surface antigen of Streptococcus mutans. Arch. Oral Biol 35 Suppl, 33S–38S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Troffer-Charlier N, Ogier J, Moras D & Cavarelli J (2002) Crystal structure of the V-region of Streptococcus mutans antigen I/II at 2.4 A resolution suggests a sugar preformed binding site. J. Mol. Biol 318, 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson MR, Rajashankar KR, Patel MH, Robinette RA, Crowley PJ, Michalek S, Brady LJ & Deivanayagam C (2010) Elongated fibrillar structure of a streptococcal adhesin assembled by the high-affinity association of alpha-and PPII-helices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 5983–5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nylander A, Forsgren N & Persson K (2011) Structure of the C-terminal domain of the surface antigen SpaP from the caries pathogen Streptococcus mutans. Acta Crystallograph. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun 67, 23–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larson MR, Rajashankar KR, Crowley PJ, Kelly C, Mitchell TJ, Brady LJ & Deivanayagam C (2011) Crystal structure of the C-terminal region of Streptococcus mutans antigen I/II and characterization of salivary agglutinin adherence domains. J. Biol. Chem 286, 21657–21666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heim KP, Crowley PJ, Long JR, Kailasan S, McKenna R & Brady LJ (2014) An intramolecular lock facilitates folding and stabilizes the tertiary structure of Streptococcus mutans adhesin P1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 15746–15751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brady LJ, Piacentini DA, Crowley PJ & Bleiweis AS (1991) Identification of monoclonal antibody-binding domains within antigen P1 of Streptococcus mutans and cross-reactivity with related surface antigens of oral streptococci. Infect. Immun 59, 4425–4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homonylo-McGavin MK & Lee SF (1996) Role of the C terminus in antigen P1 surface localization in Streptococcus mutans and two related cocci. J. Bacteriol 178, 801–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Homonylo-McGavin MK, Lee SF & Bowden GH (1999) Subcellular localization of the Streptococcus mutans P1 protein C terminus. Can. J. Microbiol 45, 536–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oli MW, Otoo HN, Crowley PJ, Heim KP, Nascimento MM, Ramsook CB, Lipke PN & Brady LJ (2012) Functional amyloid formation by Streptococcus mutans. Microbiology 158, 2903–2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hammer ND, Schmidt JC & Chapman MR (2007) The curli nucleator protein, CsgB, contains an amyloidogenic domain that directs CsgA polymerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 12494–12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dueholm MS, Søndergaard MT, Nilsson M, Christiansen G, Stensballe A, Overgaard MT, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T, Otzen DE & Nielsen PH (2013) Expression of Fap amyloids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. fluorescens, and P. putida results in aggregation and increased biofilm formation. MicrobiologyOpen 2, 365–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang W, Bhatt A, Smith AN, Crowley PJ, Brady LJ & Long JR (2016) Specific binding of a naturally occurring amyloidogenic fragment of Streptococcus mutans adhesin P1 to intact P1 on the cell surface characterized by solid state NMR spectroscopy. J. Biomol. NMR 64, 153–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banas J A (2004) Virulence properties of Streptococcus Mutans. Front. Biosci 9, 1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taglialegna A, Navarro S, Ventura S, Garnett JA, Matthews S, Penades JR, Lasa I & Valle J (2016) Staphylococcal Bap Proteins Build Amyloid Scaffold Biofilm Matrices in Response to Environmental Signals. PLoS Pathog. 12, 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Martino P (2016) Bap: A New Type of Functional Amyloid. Trends Microbiol. 24, 682–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van NG, Van S der V, Reiter DM & Remaut H (2018) The Role of Functional Amyloids in Bacterial Virulence. J. Mol. Biol 430, 3657–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marley J, Lu M & Bracken C (2001) A method for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 20, 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]