Abstract

Squalene is a cancer chemo-preventive and skin protective agent with high commercial demand. Here, we report for the first time that the green tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves is a surprisingly rich plant-based source of squalene. Young and tender leaves and old and turf leaves were collected at four different collecting seasons (April–August). Lipophilic compounds in the leaves and commercial green teas were extracted with hexane. The squalene contents in the hexane extracts varied greatly with the types of the leaves and collecting seasons. The hexane extract of turf leaves contained significantly higher contents of squalene than the extract of tender leaves. The hexane extract of the turf leaves collected in August contained the highest content of squalene (29.2 g/kg extract). This represents the first report on the qualitative and quantitative information on squalene in green tea leaves.

Keywords: Squalene, Camellia sinensis leaves, Green tea, Lipophilic compound

Introduction

Squalene is a natural hydrocarbon (a triterpene) with six isolated double bonds. Squalene is a precursor for the synthesis of various important biomolecules including sterols, steroid hormones, and vitamin D in the human body. Squalene has been reported to be a potential cancer chemopreventive substance (Newmarks, 2006; Reddy and Couvreur, 2009; Smith, 2005) and an important component possessing a positive physiological role in the skin such as assisting hydration, protecting skin from environmental factors, repairing damaged skin, and rejuvenating aged-skin (Huang et al., 2009; Viola and Viola, 2009). Shark liver oil is originally the main commercial source of squalene. However, the use of shark liver oil in squalene production has drawn a high public concern on the endangered species, and the possible existence of pollutants and pathogens. Finding new natural sources, especially of plant origin has drawn a great interest (Popa et al., 2015). Amaranth seed has been known to be the richest plant-based source of squalene (Popa et al., 2015). The squalene content in the hexane extract of amaranth seed is in the range of 40–80 g/kg extract (Budge & Barry, 2019; He & Corke, 2003; He et al., 2002; Ortega et al., 2012). Olive oil has been reported to contain a considerable quantity of squalene (0.49–5.6 g/kg oil) (Beltrán et al., 2016; Frega et al., 1992; Grigoriadou et al., 2007; Nergiz and Celikkale, 2011; Salvo et al., 2017). Recently, Pokkantaet al. (2019) reported that cold-pressed rice bran oil also contained considerable amount of squalene (3.2 g/kg). The other vegetable oils have been reported to contain a low quantity of squalene: sunflower oil (0-0.1 g/kg), soybean oil (0.03–0.2 g/kg), grape seed oil (0.141 g/kg), hazelnuts oil (0.279 g/kg), peanut oil (0.274 g/kg), corn oil (0.1–0.17 g/kg), and apricot kernel oil (0.13–0.44 g/kg) (Frega et al., 1992; Grigoriadou et al., 2007; Nergiz and Celikkale, 2011; Rudzińska et al., 2017).

Green tea, a product prepared from the leaves of C. sinensis, is one of the most popular beverages in the world. Green tea beverages have a range of beneficial functions to human health including cholesterol reduction, antioxidant activity, anticancer activity, and preventive function against cardiovascular disease (Oya et al., 2017; Zaveri, 2006). Catechins, hydrophilic substances, in the green tea beverages have been extensively studied as a main active component for the beneficial functions. However, the lipophilic component in green tea leaves was scarcely studied (Choi et al., 2016). In addition, the qualitative and quantitative information on squalene in green tea leaves has never been previously reported.

Here, we report for the first time the qualitative and quantitative information of squalene in the hexane extracts of young (tender) leaves and old (turf) leaves of C. sinensis collected in 4 different seasons (April–August). Furthermore, the contents of squalene in the hexane extracts obtained from commercial green tea products and spent green teas (after infusion) were determined.

Materials and methods

Materials

Authentic squalene was purchased from Sigma (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, Mo., USA). Young leaves (a terminal bud and following two tender leaves) and old leaves (turf and thick leaves) of C. sinensis (green tea tree) were hand-picked in four different seasons (April, July, August, and September) at a local farm located in Jeong-eup, Korea. The leaves were harvested in the same assigned sector of the same farm. The commercial green tea products (A–C) were purchased from local markets; (A) Dongwon Bosung Nokcha (Dongwon F&B Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea), (B) Nokchawon Jaksulcha (Nokchawon Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea), (C) Sukrock Jaksul Okrock (Amore Pacific Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Extraction of nonpolar components from C. sinensis leaves

For the extraction of nonpolar components, the collected raw C. sinensis leaves were first frozen in a deep freezer at − 80 °C. Then, the frozen C. sinensis leaves were freeze-dried under vacuum. The freeze-dried leaves were ground and passed through a sieve (60 mesh) to obtain a fine dried powder. The dried powders were stored in a deep freezer at − 80 °C until used. The dried leaf powder or green tea product powder (50 g) was transferred into a glass flask (2 L capacity). Then, the nonpolar components in the leaves were extracted with hexane (800 mL) in a shaking water bath at 40 °C and 126 rpm for 30 min. This extraction step was repeated once again. The green tea leave extract was obtained by evaporating the solvent (hexane) with a rotatory vacuum evaporator (Eyela N-1000, Eyela Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Tokyo, Japan) at 40 °C.

Green tea infusion

For the green tea infusion, green tea (25 g) was transferred into a glass beaker. Then, 2.5 L of hot water (82 °C) was added to the green tea leaves and left for 5 min. The spent tea leaves were collected and freeze-dried. Lipophilic components in the spent tea leaves were extracted with hexane as described above.

Saponification

The saponification of the hexane extract was done according to the previous report with a slight modification (Choi et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2011). The saponification of the hexane extract was conducted in a water bath at 60 °C for 90 min with ethanolic KOH solution (12% KOH in ethanol) in a test tube. The sample tube was then cooled with running tap water. Double distilled water (20 mL) and n-hexane (20 mL) were added to the sample tube to extract the unsaponifiable. The upper hexane layer was collected from the sample tube. This hexane-extraction step was repeated one more time. The collected hexane layers were pooled in a volumetric flask (100 mL capacity), and then the volume was made up with hexane.

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry for identification

The identification of squalene in samples was performed by a GC–MS with a full scan mode. The identity of squalene was first checked by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) GC mass spectral library (version NIST 14). Then, the mass spectrum of the compound was compared with that of authentic squalene. The identity of squalene was doubly verified by the retention time of authentic squalene. The GC–MS analysis was carried out using a GC–MS system comprising of a GC (2010 Plus, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) and triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (TQ8030, Shimadzu). The injector, MSD transfer line, and ion-source temperatures were 315, 310, and 280 °C, respectively. The column used was a nonpolar capillary column (RTX-5MS, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm film thickness, Restek Co., Bellefonte, PA, USA). The injection split ratio was 20:1. The oven temperature was programmed with an initial temperature of 250 °C for 1 min, then an increase at the rate of 5 °C/min to 300 °C with an 18-min holding at the final oven temperature. Helium gas was used as a carrier gas with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

Quantitative analysis and method validation

The quantitative analysis of squalene was performed by a GC-FID (2010 Plus, Shimadzu). The injector and detector temperatures were 280 and 300 °C. The column used was a nonpolar capillary column (RTX-5MS, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm film thickness, Restek Co.). The injection split ratio was 20:1. The oven temperature was programmed with an initial temperature of 250 °C for 1 min, then an increase at the rate of 5 °C/min to 300 °C with an 18-min holding at the final oven temperature. Helium gas was used as a carrier gas with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Squalene standard stock solution was prepared at the concentration of 10 mg/mL. The working standard solutions (0–500 μg/mL) were prepared by serial dilution of the standard stock solution. The contents of squalene in samples were calculated with a standard calibration curve obtained from authentic squalene. The analytical method was validated in terms of the linearity of the standard curve, the limit of detection (LOD), the limit of quantification (LOQ), recovery (accuracy), and precision (intraday- and inter-day repeatability). For the recovery test, the green tea sample with a known amount of spiked squalene (200 μg/0.01 g extract) was prepared. Then the squalene contents in the spiked sample and non-spiked samples were determined for the calculation of recovery. For the intra-day precision of the method, 8 times repeated analysis was conducted at the same date with the squalene standard solutions at the three different concentrations (25, 125, and 250 ppm). To check the inter-day precision, a green tea hexane extract sample (old and turf leaves) was repeatedly analyzed for the 4 different days. The intraday and inter-day precisions were expressed as % relative standard deviation (%RSD).

Statistical analysis

The quantitative analysis for the determination of squalene in the extracts was conducted in triplicate. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s multiple-range test (a Post-hoc test) was carried out to check the statistical significance of the squalene contents in the extracts at α = 0.05 by using an SPSS statistical analysis program (SPSS 14.0K, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Identification of squalene

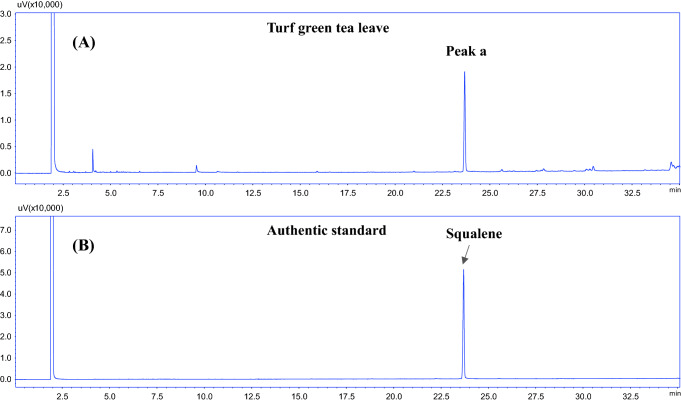

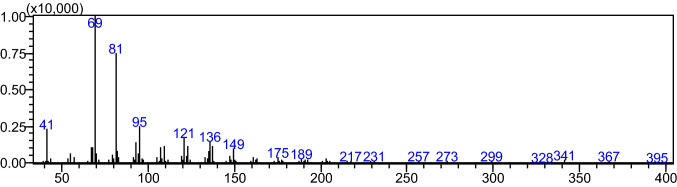

Figure 1A shows the representative gas chromatogram of the unsaponifiable of green tea leaves hexane extract. As shown in the gas chromatogram (Fig. 1A), the presence of an unknown compound (peak a: tR, 22.70 min) in the hexane extract of green tea leaves was observed. The identification of the unknown compound was performed using GC–MS in a full scan single mass spectrometry mode (Fig. 2). The compound A was tentatively assigned as squalene based on NIST GC–MS library (version NIST 14) searching result. The identity of the compound A was confirmed by comparing the GC retention and the mass spectrum of the authentic compound (Fig. 1B). As shown in Fig. 1A, B, the gas chromatographic retention time of authentic squalene was exactly the same as that of the unknown compound (peak a).

Fig. 1.

GC chromatograms of hexane extract unsaponifiable of Camellia sinensis leaves (A) and authentic squalene standard (B)

Fig. 2.

Full scan mass spectra of peak a by GC–MS analysis

Method validation

The analytical method was validated in terms of the linearity of the calibration curves, LOD and LOQ, intra-day and inter-day repeatability (precision), and recovery (accuracy) of the analytical method. The coefficient of determination (r2) of the standard calibration curve was 0.9997, showing high linearity over the wide concentration range (5–500 μg/mL) (data not shown). The LOD, LOQ, intra- and inter-day repeatability, and recovery data are shown in Table 1. The LOD and LOQ were 0.7 and 2.5 μg/mL, respectively. The relative standard deviation (RSD) of the intra-day repeated analysis of the standard samples at the three different concentrations (25, 125, and 250 ppm) was less than 1.1%. The RSD of the data obtained by the inter-day repeatability with the 4 different day analysis of the green tea leaves (old and turf) was 2.58%, showing high precision of the adapted method. The recovery of the spiked squalene in hexane extract was 92.6%, showing the high accuracy of the analytical method.

Table 1.

Sensitivity, recovery, intra-day and inter-day precisions of the analytical method

| Sensitivity1 | Recovery (%)2 | Intra-day precision (%RSD)3 | Inter-day precision (% RSD)4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOD (μg/kg) | LOQ (μg/kg) | Spiked at 200 μg/0.01 g | 25 ppm | 125 ppm | 250 ppm | |

| 0.7 | 2.5 | 92.6 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 1.10 | 2.58 |

1LOD and LOQ were calculated by multiplying the ratio of signal to noise (S/N) by 3 and 10, respectively

2Recovery was based on the analysis of the green tea extract spiked at 200 μg/0.01 g

3Intra-day repeatability was obtained from 8 repeated analysis. Intra-day repeatability of contents of authentic squalene was obtained from 8 repeated analysis of squalene standard solution at the three different concentration levels

4Inter-day repeatability was obtained from 4 different date repeated analysis of green tea leave extract

Squalene content

The yields and squalene contents of hexane extracts of young and old leaves collected in four different seasons (from April to September) from a local farm are shown in Table 2. The yield of hexane extract was also greatly dependent on the types of green tea leaves (Table 2). The yields of hexane extract from tender leaves and turf leaves were in the range of 1.53–1.63% and 5.07–7.23%, respectively. The results showed that the lipophilic compound contents in turf leaves were considerably higher than those in tender leaves. The results also showed that the seasonal variations in the lipophilic compound contents in the leaves was relatively low. The squalene contents in the hexane extracts obtained from the leaves differed greatly with both leaf types and collecting season, ranging from 1.6 to 29.2 g/kg. The squalene contents in the hexane extracts of old leaves were significantly higher than those in the young leaves (p < 0.05). The squalene contents in young and tender leaves harvested in April, July, August, and September were 1.6, 13.6, 14.0, and 11.5 g/kg extract, respectively. The tender leaves obtained in early spring (April) contains a very low quantity of squalene. From April to August, the amount of squalene contained in green tea leaves increased. After then, the squalene content in the tender leaves decreased. The squalene contents in old and turf leaves collected in April, July, August, and September were 15.5, 22.8, 29.2, and 17.7 g/kg extract, respectively. The squalene content in turf leaves was also greatly dependent on the collecting season. The squalene content in the hexane extract of old leaves collected in August was the highest (p < 0.05). It is interesting to note that squalene content was high in leaves harvested in hot and sunny seasons (August). However, the squalene content was very low in the leaves (first sprouted very tender leaves in early spring) harvested in April, with very mild temperatures and low sunlight. In such an early spring season with the mild weather conditions, the squalene is not necessarily fully synthesized and excreted to the surface of the leaves. The role of squalene in the leaves may be related to its’ protective action of green tea leaves from the harsh environment such as preventing water loss and ultraviolet radiation damages, and defending against pathogens, which are more prevail in the hot and sunny environment. The squalene content (29.2 g/kg) in the hexane extract of old leaves collected in August was almost comparable to that in hexane extract of Amaranthus seed (40–80 g/kg hexane extract) (He and Corke, 2003; He et al., 2002; Ortega et al., 2012). We also obtained the hexane extract from the commercial green tea products and determined their squalene contents. The squalene contents in the hexane extracts of commercial green tea products were found to be in a range of 1.3–8.2 g/kg extract (Table 3). The relatively low contents of squalene in the commercial green tea products were found as compared to that in turf green tea leaves. That can be explained by that commercial green teas were produced from tender leaves, which originally contained a low level of squalene. It was found that the squalene contents in the infused green tea products (waste) were significantly higher than those in green tea products before infusion (Table 3). Squalene was not leached out from green tea during infusion. The result suggested that the waste from the green tea beverage industry could be a valuable source for squalene.

Table 2.

Squalene contents in young and tender and old and turf leaves of C. sinensis collected at different seasons1

| Collecting season | Young and tender leaves | Old and turf leaves | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squalene in extract (g/kg)2 | Extract yield (%)3 | Squalene in extract (g/kg)2 | Extract yield (%)3 | |

| April | 1.63 ± 0.39c | 1.79 ± 0.08a | 15.48 ± 1.43d | 5.17 ± 0.00b |

| July | 13.55 ± 0.08a | 1.60 ± 0.06b | 22.84 ± 0.04b | 5.07 ± 0.04b |

| August | 13.99 ± 0.10a | 1.53 ± 0.09c | 29.17 ± 1.36a | 5.59 ± 0.01b |

| September | 11.53 ± 0.09b | 1.63 ± 0.14ab | 17.71 ± 1.08c | 7.23 ± 0.29a |

1The values with same superscript letter within the same column are not significantly different at α = 0.05

2Contents represent the mean of quadruplicate analysis ± standard deviation (g/kg)

3Yield of hexane extract (%) obtained from green tea leaves

Table 3.

Squalene contents in hexane extracts of commercial green tea leave products

| Green tea products | Before infusion1 | After infusion1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squalene in extract (g/kg)2 | Extract yield (%)3 | Squalene in extract (g/kg)2 | Extract yield (%)3 | |

| Green tea A | 8.17 ± 0.02b | 3.02 ± 0.18A | 8.73 ± 0.41a | 3.25 ± 0.21A |

| Green tea B | 5.18 ± 0.24b | 2.04 ± 0.02B | 5.94 ± 0.38a | 2.27 ± 0.11A |

| Green tea C | 1.25 ± 0.03 | 1.45 ± 0.02 | ND | ND |

ND not determined

1The values with same superscript letter within same row are not significantly different at α = 0.05

2Contents represent the mean of quadruplicate analysis ± standard deviation (g/kg)

3Yield of hexane extract (%) obtained from green tea products

The most important sources of commercial squalene were shark liver oil, olive oil, and amaranth oil. The use of shark liver oil for squalene has been avoided due to the considerable public concern. The squalene content in the hexane extract of amaranth seed, the richest plant-based source of squalene, is in the range of 40–80 g/kg extract (Budge & Barry, 2019; He and Corke, 2003; He et al., 2002; Ortega et al., 2012). The squalene content in olive oil, a rich source of squalene, is in the range from 0.49 to 5.6 g/kg (Beltrán et al., 2016; Frega et al., 1992; Grigoriadou et al., 2007; Lanzon et al., 1994; Nergiz and Celikkale, 2011; Salvo et al., 2017). Our present study showed that squalene contents in the hexane extract of the turf leaves of C. sinensis reached to maximum of 29.2 g/kg, which is almost comparable to that in the hexane extract of Amaranthus seed. Amaranthus seed is an expensive crop with high commercial value, whereas the old green tea leaves do not have any commercial value due to its astringency and bitter taste. The present results clearly showed that hexane extract of old and turf C. sinensis leaves has a high potential as a valuable plant-based rich source of squalene, an important lipid-soluble cancer chemo-preventive and skin protective component with significant commercial demand.

In brief conclusion, the presence of squalene in C. sinensis leaves was positively identified for the first time. The squalene contents in the hexane extracts of green tea leaves greatly varied with the leaf types and collecting season. The hexane extract of useless turf green tea leaves collected in August was found to be an exceptionally rich source of squalene, reaching 29.2 g/kg extract, which was almost comparable to that in the hexane extract of Amaranthus seed (the richest plant-based source of squalene). The spent commercial green tea also contained a considerable amount of squalene. The present study showed unambiguously for the first time that the hexane extracts obtained from the turf green tea leaves (useless leaves) and spent green tea (waste obtained after infusion) could be a valuable plant-based source of squalene for its applications in functional foods, dietary supplement, and cosmetics.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported in part by Korean Ministry for Food, Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries through iPET (Project Number 113020-3).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Su Yeon Park, Email: vov_suyeon@naver.com.

Sol Ji Choi, Email: solji3538@naver.com.

Hee Jeong Park, Email: rhdwbgmlwjd@naver.com.

Sang Yong Ma, Email: syma@woosuk.ac.kr.

Yong Il Moon, Email: yimoon@woosuk.ac.kr.

Sang-Kyu Park, Email: nutrapol@nambu.ac.kr.

Mun Yhung Jung, Email: munjung@woosuk.ac.kr.

References

- Beltrán G, Bucheli ME, Aguilera MP, Belaj A, Jimenez A. Squalene in virgin olive oil: Screening of variability in olive cultivars. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016;118:1250–1253. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201500295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SM, Barry C. Determination of squalene in edible oils by transmethylation and GC analysis. MethodsX. 2019;6:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SJ, Park SY, Park JS, Park S, Jung MY. Contents and compositions of policosanols in green tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves. Food Chem. 2016;204:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frega N, Bocci F, Lercker G. Direct gas chromatographic analysis of the unsaponifiable fraction of different oils with a polar capillary column. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1992;69:447–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02540946. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadou D, Androulaki A, Psomiadou E, Tsimidou MZ. Solid phase extraction in the analysis of squalene and tocopherols in olive oil. Food Chem. 2007;105:675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.12.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He HP, Corke H. Oil and squalene in Amaranthus grain and leaf. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:7913–7920. doi: 10.1021/jf030489q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He HP, Cai Y, Sun M, Corke H. Extraction and purification of squalene from Amaranthus grain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:368–372. doi: 10.1021/jf010918p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z-R, Lin Y-K, Fang J-Y. Biological and pharmacological activities of squalene and related compounds: potential uses in cosmetic dermatology. Molecules. 2009;14:540–554. doi: 10.3390/molecules14010540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung DM, Lee MJ, Yoon SH, Jung MY. A gas chromatography tandem quadrupole mass spectrometric analysis of policosanols in commercial vegetable oils. J. Food Sci. 2011;76:C891–C899. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzon A, Albi T, Cert A, Gracián J. Hydrocarbon fraction of virgin olive oil and changes resulting from refining. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1994;71:285–291. doi: 10.1007/BF02638054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nergiz C, Celikkale DC. The effect of consecutive steps of refining on squalene content of vegetable oils. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011;48:382–385. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0190-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmarks HL. Olive oil, and cancer risk: review and hypothesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006;889:193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega JAA, Zavala AM, Hernández MC, Reyes JD. Analysis of trans fatty acids production and squalene variation during amaranth oil extraction. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2012;10:1773–1778. [Google Scholar]

- Oya Y, Mondal A, Rawangkan A, Umsumarng S, Iida K, Watanabe T, Kanno M, Suzuki K, Li Z, Kagechika H, Shudo K, Fujiki H, Suganuma M. Down-regulation of histone deacetylase 4, -5 and -6 as a mechanism of synergistic enhancement of apoptosis in human lung cancer cells treated with the combination of a synthetic retinoid, Am 80 and green tea catechin. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017;42:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokkanta P, Sookwong S, Tanang M, Setchaiyan S, Boontakham P, Mahatheeranont S. Simultaneous determination of tocols, γ-oryzanols, phytosterols, squalene, cholecalciferol and phylloquinone in rice bran and vegetable oil samples. Food Chem. 2019;271:630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa O, Băbeanu NL, Popa I, Niţă S, Dinu-Pârvu CL. Methods for obtaining and determination of squalene from natural sources. BioMed Res. Int. 2015;2015:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2015/367202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy LH, Couvreur P. Squalene: A natural triterpene for use in disease management and therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009;61:1412–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudzińska M, Górnaś P, Raczyk M, Soliven A. Sterols and squalene in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) kernel oils: the variety as a key factor. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017;31:84–88. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2015.1135146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvo A, La Torre GL, Rotondo A, Mangano V, Casale KE, Pellizzeri V, Clodoveo ML, Corbo F, Cicero N, Dugo G. Determination of squalene in organic extra virgin olive oils (EVOOs) by UPLC/PDA using a single-step SPE sample preparation. Food Anal. Methods. 2017;10:1377–1385. doi: 10.1007/s12161-016-0697-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ. Squalene: potential chemopreventive agent. Expert Opin. Inv. Drug. 2005;9:1841–1848. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.8.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola P, Viola M. Virgin olive oil as a fundamental nutritional component and skin protector. Clin. Dermatol. 2009;27:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaveri NT. Green tea and its polyphenolic catechins: Medicinal uses in cancer and noncancer applications. Life Sci. 2006;78:2073–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]