Abstract

The presentation of radiology exams can be enhanced through the use of dynamic images. Dynamic images differ from static images by the use of animation and are especially useful for depicting real-time activity such as the scrolling or the flow of contrast to enhance pathology. This is generally superior to a collection of static images as a representation of clinical workflow and provides a more robust appreciation of the case in question. Dynamic images can be shared electronically to facilitate teaching, case review, presentation, and sharing of interesting cases to be viewed in detail on a computer or mobile devices for education. The creation of movies or animated images from radiology data has traditionally been challenging based on technological limitations inherent in converting the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) standard to other formats or concerns related to the presence of protected health information (PHI). The solution presented here, named Cinebot, allows a simple “one-click” generation of anonymized dynamic movies or animated images within the picture archiving and communication system (PACS) workflow. This approach works across all imaging modalities, including stacked cross-sectional and multi-frame cine formats. Usage statistics over 2 years have shown this method to be well-received and useful throughout our enterprise.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10278-020-00325-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Education, Presentation, Movie, GIF, Cine, Anonymization

Background

Radiological film, used for many years to create and store radiology images, had numerous frustrating disadvantages when attempting to archive, retrieve, and share images. Efforts to resolve these problems led to the widespread implementation of picture archiving and communications systems (PACS), which allow transfer, storage, retrieval, and interpretation of digital images and their associated metadata within the hospital environment. This has revolutionized radiology, allowing faster interpretation of images with increased accuracy, enhanced workflows with lower costs, and an overall improvement in the standard of care for patients [1].

PACS has had a strong impact on training and education. Surveys of radiology residents using PACS for image interpretation training have documented resident belief that this digital approach provided both better education and improved patient care. In particular, the surveyed residents favored PACS over hard-copy images for the ease of manipulation, improved resolution, and the ability to easily note and share pathologic conditions [2]. Dynamic images, however, take these advantages to even higher levels of interaction between residents and the imaging process. A recent study showed that the use of a novel educational method using dynamic images, specifically movies of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MR) in the anatomy classroom, improved student performance on examinations and preparedness for clinical clerkships [3]

Sharing and exporting digital medical images come with known patient privacy challenges. PACS systems use the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) standard format which combines large amounts of patient and exam metadata along with the image data itself; for example, a DICOM file may have patient identifiers embedded in the metadata, thus ensuring that no mismatch can occur [4]. Although clearly an advantage for clinical workflow, this embedding creates problems in the context of data anonymization for research or educational purposes. Although this information can sometimes be removed by “scrubbing” programs, it often proves more difficult than expected and complete removal may even be impossible. One challenging example beyond relatively simple metadata extraction would be a volume rendered image of a patient’s head which naturally provides a rendition of their appearance [5, 6]

An additional challenge for this use case of creating dynamic files for educational purposes is that it is not typically straightforward to generate these files. One previously described method is PACSstacker, a plug-in for PowerPoint which allows the creation of stackable images simulating the scrolling functionality possible at a clinical workstation [7]. The disadvantage to this system is that PowerPoint is generally ill-suited for large numbers of images; modern cross-sectional studies can contain hundreds or even thousands of slices. Alternative approaches such as converting images into animated graphic interchange files (GIFs) ready for embedding in presentations have been developed, but these have been described as requiring significant amounts of manual work [8]. In general, previous methods are time-consuming, inefficient, and often lead to excessively large file sizes. Journal articles with tips and tricks for radiology presenters exist [9], but in general the difficulties of incorporating multimedia within presentations are many-fold.

Once a dynamic image is created, it can sometimes be difficult to share or present. While static images are relatively easy to embed in webpages or presentation software, videos are sometimes reliant upon the host computer containing the proper coding/decoding program (or “codec”) to decompress the video file for playback. This compression/decompression routine allows relatively large movies to be stored in small file sizes which is helpful for media-rich presentations. The use of animated GIFs often circumvents this problem in that GIFs are similarly easy to embed just like static images and are compatible with web browsers and most desktop/mobile platforms without additional plug-ins. Although file sizes are relatively small, GIFs are generally much larger than compressed movie formats such as MPEG4.

Our approach to solve these problems has resulted in Cinebot, a custom software extension we have developed which generates anonymized dynamic movie and GIF files directly from a given PACS image or series via a simple, one-click method (Fig. 1). Series or multi-frame images are converted into GIF animations or MPEG4 video (Online Resources 1–4), both of which are fairly well-established and are typically easy to share and present. This method delivers small file sizes (Table 1) with a high level of quality, even after compression, which can then be shared via email, mobile messaging, wiki or other web-based collaborative environments, or through presentation software. Its automatic anonymization routine removes patient identifying information with high reliability with a manual screening process at the end to ensure full anonymization for patient privacy and regulatory compliance. As a built-in add-on to PACS, it removes the cumbersome manual steps from the individual user. Cinebot has substantially lowered the barrier to creating dynamic images within our institution and has catalyzed teaching, presentation, and sharing of interesting cases.

Fig. 1.

Example of Cinebot context menu. The right-click context menu is embedded into the institutional PACS system and allows “one-click” creation of a cine or GIF animation from any study in PACS

Table 1.

Example file sizes of animations created using Cinebot

| Modality | File type | File size |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic ultrasound | MPEG4 | 568.3 kb |

| X-ray angiogram | GIF | 603.8 kb |

| Head CT | MPEG4 | 1.2 mb |

| Head MRI | MPEG4 | 225.3 kb |

| X-ray angiogram | GIF | 4.1 mb |

Methods

Institutional Review Board (IRB) exemption was obtained. We integrated a custom JavaScript plug-in into our PACS that allows a user to request a movie by right clicking on any radiology image (Fig. 1).

Pertinent context information such as user, study, and patient information and service object pair (SOP) unique identifier (UID), an attribute defined in the DICOM standard that uniquely identifies a DICOM object, is posted to our operational server for processing. We then use the dcm4che (dcm4che.org) toolkit to find and retrieve the study from our DICOM archive. For stacked cross-sectional imaging such as CT, the series of interest is filtered; for ultrasound, the pertinent image including cine frames is selected; and for multi-phase exams such as multi-parametric MR, the acquisition phase of interest is acquired. Paperwork, secondary captures, and images labeled as having burned-in annotations are excluded. For each image in the series, cine, or acquisition, the pixel data is extracted again using the dcm4che toolkit. Ultrasound images are cropped using the ImageMagick library (https://imagemagick.org) based on coordinates contained in the Sequence of Ultrasound Regions [0018,6011] DICOM tag to exclude burned-in patient information. Finally, images are compiled into mp4 or GIF format using the avconv (https://libav.org/avconv.html) library and emailed internally to the requesting user using an Active Directory (Microsoft) query to find the user’s email address for a final check to ensure protected health information (PHI) is excluded before presentation or sharing.

Results

Once implemented at the local institution, usage statistics for the Cinebot software were tracked across an evaluation period of June 2017, to July 2019. These were used to evaluate uptake and overall effectiveness of the application.

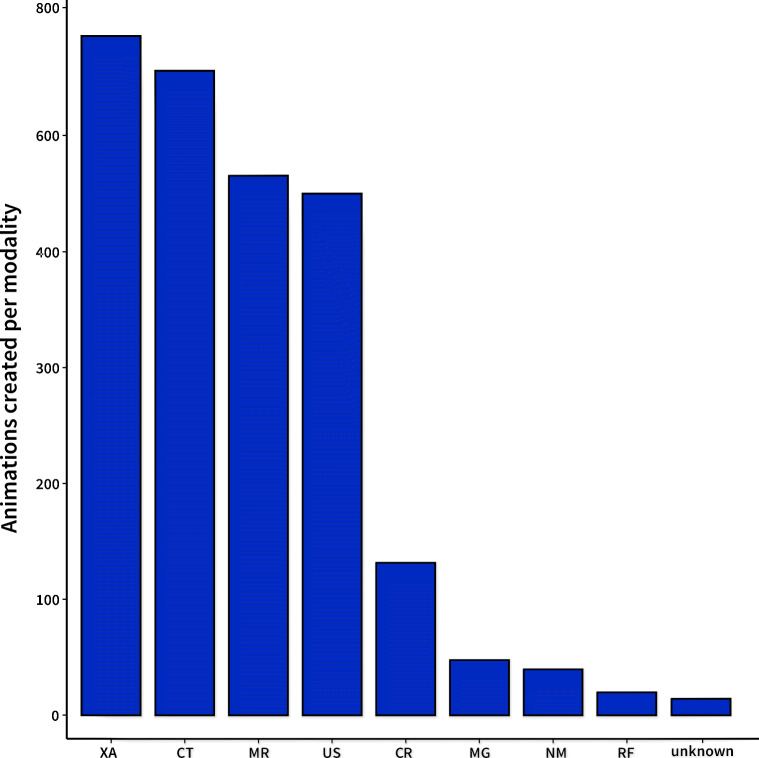

In the evaluation period, 59 Cinebot users created 2758 dynamic images (1–433 per user) from 1263 radiological patient exams which included 1332 modalities as some exams included more than one modality. Significant peaks in usage were observed in January 2018 (204 dynamic images); June 2018 (196 dynamic images); and April 2019 (208 dynamic images) with a minimum of 16 images seen in July 2018 (Fig. 2). Users created dynamic images predominantly from exams that included the angiography modality, comprising 770 of the total number. However, cross-sectional imaging techniques (MR/CT) were the greatest source of images in aggregate, with 712 images (CT) and 571 images (MR) being created during the evaluation period (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Usage statistics during evaluation period. The number of dynamic images created by Cinebot users was tracked across the evaluation period of June 2017 to July 2019

Fig. 3.

Breakdown of cine/GIFs created. The dynamic images created by Cinebot during the evaluation period were divided according to modality. XA, x-ray angiography, 770; CT, computed tomography, 712; MR, magnetic resonance imaging, 571; US, ultrasound, 482; CR, computed radiography, 139; MG, mammography, 36; NM, nuclear medicine, 35; RF, fluoroscopy, 8; blank or unknown, 5.

It is impossible to quantitatively compare time to create movies between Cinebot and old methods as we do not have usage statistics from the variable manual methods previously used. However, since it takes a matter of seconds to click a single button to initiate the movie creation process, it is probably reasonable to state that user time and steps have decreased.

Discussion

The usage statistics demonstrated peaks in January and June of 2018 and in April of 2019, with a dip in July 2018 (Fig. 2). These trends are believed to correlate with the general ebb and flow of work and experience within the institute. The January and April peaks are believed to represent the increased number of residents preparing for conferences that required presentation images, leading to the subsequent peak in usage. June, similarly, is immediately prior to graduation for many radiology residents, many of whom take examples of interesting cases with them. Each July sees the arrival of many new residents with limited experience with PACS, so that may explain the natural decrease in the use of plug-in systems such as Cinebot during that time. The generally high number of angiography images is believed to be due to weekly section conferences; the use of animated images facilitates the presentation and review of large numbers of cases.

The use of Cinebot has significantly facilitated the teaching, presentation, and sharing of relevant cases within our institution. The highly reliable anonymization process along with a simple manual check ensures that such sharing does not violate patient privacy or pertinent regulations. The resulting dynamic images (Online Resource 1–4) have been used for sharing interesting cases, teaching, case conferences, formal presentation, and through the use of an internal Wiki-based collaborative authoring and learning environment that allows the posting of image series and videos for teaching purposes and which has previously been shown to provide effective knowledge-management in hospital environments [10].

Based on our experience, limitations and potential improvements to Cinebot have been identified:

Our current system, while having some advantages in its simplicity, does not allow customization of the results. The user cannot choose GIF versus MPEG4 and the speed at which the animation plays, or crop the file at all. We have considered an optional pop-up menu to allow some of these customization features.

It is very difficult to absolutely guarantee anonymization across the wide spectrum of modalities, secondary captures, reconstructions, and annotations that exist in our enterprise. Our system works for most cases, but we require an internal manual screening step; there may be more intelligent ways to accomplish this.

One particularly frustrating limitation is that our current PACS does not provide window/level information through its integration API which could be used when extracting the pixel data to create a movie that matches the user-specified window/level. This would be useful for cases such as pulmonary embolus CT exams where typically the window/level is manually adjusted to optimize pulmonary artery evaluation or any other exam where this may enhance the finding of interest. While we would prefer to capture this information from our PACS, this could also be addressed through a pop-up menu with user input as described above.

Conclusion

We present a simple and straightforward mechanism for creating dynamic images from PACS. This tool has been enthusiastically received at our institution where it has facilitated improved presentation, teaching, case review, and sharing of interesting findings both internally and externally.

Electronic supplementary material

(GIF 3877 kb)

(MP4 1220 kb)

(MP4 568 kb)

(GIF 4209 kb)

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Reiner BI, Siegel EL, Siddiqui K. Evolution of the digital revolution: a radiologist perspective. J Digit Imaging. 2003;16(4):324–330. doi: 10.1007/s10278-003-1743-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullins ME, Mehta A, Patel H, McLoud TC, Novelline RA. Impact of PACS on the education of radiology residents: the residents’ perspective. Academic Radiology. 2001;8(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jang HW, Oh CS, Choe YH, Jang DS. Use of dynamic images in radiology education: movies of CT and MRI in the anatomy classroom. Anat Sci Educ. 2018;11(6):547–553. doi: 10.1002/ase.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA). Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) Standard. https://www.dicom.nema.org/medical/dicom/current/output/html/part01.html. Accessed 15 June 2019.

- 5.Avrin David. HIPAA Privacy and DICOM Anonymization for Research. Academic Radiology. 2008;15(3):273. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore SM, Maffitt DR, Smith KE, Kirby JS, Clark KW, Freymann JB, Vendt BA, Tarbox LR, Prior FW. De-identification of medical images with retention of scientific research value. Radiographics. 2015;35(3):727–735. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015140244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna PC, Thapa MM, de Regt D, Weinberger E. PACStacker: an enhancement of the scientific and educational capabilities of PowerPoint. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(2):W71–W74. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yam CS, Kruskal J, Larson M. Creating animated GIF files for electronic presentations using Photoshop. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(5):W485–W490. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pomerantz Stuart R., Choy Garry. Net Assets: PowerPoint Pearls for Radiology Presentations. Part II. Radiology. 2010;255(3):687–691. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meenan C, King A, Toland C, Daly M, Nagy P. Use of a wiki as a radiology departmental knowledge management system. J Digit Imaging. 2010;23(2):142–151. doi: 10.1007/s10278-009-9180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(GIF 3877 kb)

(MP4 1220 kb)

(MP4 568 kb)

(GIF 4209 kb)