Introduction

Leishmaniasis is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania and is transmitted by the female sand fly. There are 3 clinical forms of leishmaniasis: visceral, mucosal, and cutaneous. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common of these forms with differing species causing New World and Old World disease.1 We present a case of complex cutaneous Leishmania tropica infection of the ear treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Case presentation

An 82-year-old white woman presented with a 3-month history of a plaque on the left ear. She complained that the ear was uncomfortable, but there was no pain or systemic complaints. Ten months before presentation, she visited her daughter in the Israeli West Bank settlement Ma'ale Adumim.

Her medical history included surgery for colorectal cancer complicated by adhesions, which led to painful bowel obstructions requiring several surgeries.

On examination of the left ear, there was an ill-defined firm, hyperkeratotic plaque over the superior crus of the antihelix (Fig 1). The ear was not tender. No cervical or submandibular nodes were palpated.

Fig 1.

Initial clinical presentation shows a plaque with a hyperkeratotic surface.

An incisional biopsy found granulomatous inflammation with lymphocytes and plasma cells. There were organisms within the histiocytes, which were negative with Gomori Methenamine-silver nitrate stain and periodic acid–Schiff stain. The organisms were Giemsa positive. The histopathologic features of this patient's biopsy are included in a previously published report.2

Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing performed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the organisms as L tropica.

Treatment

The patient was treated with 3 courses of PDT. The first 2 PDT sessions were 2 weeks apart. In each, hyperkeratotic papules and plaques were debrided with curettage, and aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride 10% gel was applied and occluded for four hours. The lateral surface of the ear followed by the medial surface were exposed to 75 J of red light (633 nm).

Two months later, a biopsy of a new crusted papule on the inferior margin of the left helical rim (Fig 2) showed granulomatous inflammation with surrounding lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and rare organisms identified with CD1a and Giemsa stains.

Fig 2.

Crusted papule on the inferior margin of the left helix after second photodynamic therapy treatment.

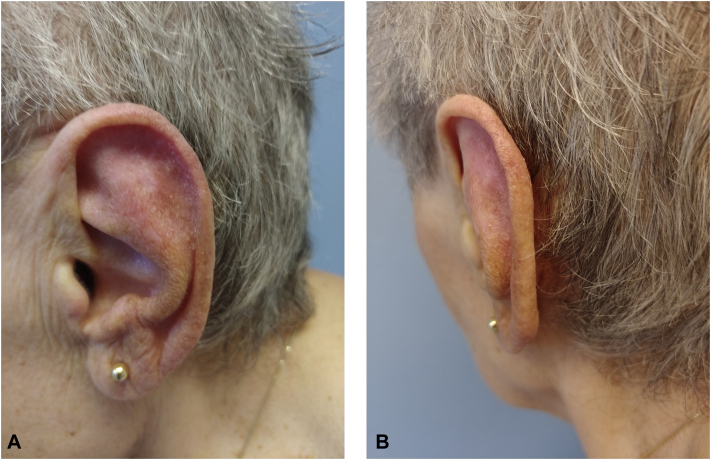

A third PDT treatment was performed 4 months after the second treatment. The patient has been clear for 22 months after the third PDT session (Fig 3, A and B).

Fig 3.

A, Lateral surface of the ear shows clinical resolution. B, Helical rim shows clinical resolution.

Discussion

In Israel, the 2 main Old World Leishmania species are Leishmania major and L tropica. L tropica is less frequent, more indolent, and generally less responsive to treatment. L tropica is concentrated in the north of Israel and in the West Bank.3 Our patient contracted L tropica in Ma'ale Adumim, an Israeli settlement in the West Bank.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis infections are divided into simple and complex. Face lesions, including those on the ear, are categorized as complex cutaneous leishmaniasis because of the higher risk of deformity from the infection as it heals and scars.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America recommends systemic oral or parenteral therapy for patients with complex cutaneous leishmaniasis.2 In this case, the CDC recommended oral miltefosine, 50 mg 3 times a day for 28 days. However, our patient declined miltefosine because of its adverse gastrointestinal side effect profile and her history of painful bowel obstructions.

Because systemic options were limited, local treatments were considered. One topical option was paromomycin. However, infections with L tropica do not have as high a response rate to topical paromomycin compared with infections caused by some other Leishmania species. The cure rate for L tropica with a combination cream of paromomycin and methylbenzethonium chloride was only 39%.2 The CDC advised against topical paromomycin because the patient's ear lesions were not ulcerative. Topical agents such as paromomycin are more effective if a lesion is ulcerated due to better absorption compared with nonulcerated skin.

We elected to treat the patient with PDT, an approved therapy for actinic lesions and superficial nonmelanoma skin cancers. There is precedent for treating Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis with PDT. Asilian et al4 in Iran compared PDT with topical paromomycin in 57 patients with L major infections. They found PDT to be safe with 93.5% clinical improvement.

In 2014, Enk et al5 published a series of 31 patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis in Israel. The authors compared supervised and self-administered treatments of PDT using daylight. Weekly treatments were given with methyl aminolevulinate occluded for 30 minutes and daylight exposure for 2.5 hours. The authors reported an overall cure rate of 89%. However, the cure rate of L tropica complex cutaneous leishmaniasis was only 33% in the supervised group and 57% in the self-administered group.

In 2016, Fink et al6 reported successful treatment of an 18-year-old Syrian woman with L tropica involving the cheek, hand, and forearm. This patient had complex cutaneous leishmaniasis, as the face was involved. Five weekly treatments of 5-aminolevulinic acid incubated for 3 hours and red light exposure at 37 J/cm2 were given. The authors do not mention if the lesions were occluded.

A case of complex cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L tropica involving the nose was reported in 2019 in a Pakistani immigrant to Australia. The patient was treated with 7 weekly treatments of methyl aminolevulinate occluded for 3 hours and exposed to 8 minutes of red light.7

Treatment of L tropica infections in children is especially difficult because the organism is resistant to treatment, and systemic drugs are more difficult to administer. In the series by Enk et al,5 all of the adults with L tropica infections were cured in both the supervised and self-administered groups. Both children (<18 years) with L tropica infection in the supervised group did not respond to therapy. Of the children with L tropica infections in the self-administered group, 5 were cured (45%), 2 did not respond to treatment, and 4 were noncompliant.5

Our patient's biopsy after her second PDT treatment was taken from a crusted papule along the external rim of the helix. It showed persistent organisms. It is possible that the organisms were not viable. However, the helical rim may have been shielded from the light when the ear was retracted during the treatment, or the rim may not have been exposed as well as the lateral and medial surfaces of the ear. In the future, the external rim of the ear should be treated as a separate position in addition to the medial and lateral surfaces of the ear.

The successful outcome may have been partially due to debridement prior to PDT sessions. Debridement may have allowed the photosensitizer and the light to penetrate more effectively.

Our case shows that PDT may be a safe and effective modality to treat complex cutaneous L tropica infections involving the ear. PDT may also be useful in children with L tropica infections when treatment with systemic therapy may be problematic. We believe cutaneous leishmaniasis is best treated under the joint care of dermatologists and tropical medicine specialists.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.Aronson N., Herwaldt B.L., Libman M. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96(1):24–45. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-84256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taxy J.B., Goldin H.M., Dickie S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: contribution of routine histopathology in unexpected encounters. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(2):195–200. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zur E. Topical treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Israel, Part 3. Int J Pharm Compd. 2019;23(5):366–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asilian A., Davami M. Comparison between the efficacy of photodynamic therapy and topical paromomycin in the treatment of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:634–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enk C.D., Nasereddin A., Alper R. Cutaneous leishmaniasis responds to daylight-activated photodynamic therapy: proof of concept for a novel self-administered therapeutic modality. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(5):1364–1370. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fink C., Toberer F., Enk A., Gholam P. Effective treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica with topical photodynamic therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14(8):836–838. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slape D.R., Kim E.N., Weller P. Leishmania tropica successfully treated with photodynamic therapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60(1):64–65. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]