Telemedicine has many definitions. However, the World Health Organization1 has defined telemedicine as follows:

The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.

Because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the consequences of either complete lockdown or milder measures, adaptation of our consultation methods became necessary.2, 3, 4, 5 With a shift from outpatient visits to online consultations to respect the required social distancing, it would be valuable to examine the use of telemedicine within the neurosurgical field. Thus, we would like to share the preliminary results of our research, which was aimed at evaluating the use of telemedicine by neurosurgeons.

From a search of the reported data, a survey of 29 questions was developed that covered demographics, the current situation owing to COVID-19, and the experience of working with telemedicine.5, 6, 7, 8 The survey was distributed among the members of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons using SurveyMonkey (Palo Alto, California, USA). The survey was first sent on May 3, 2020, with reminders sent afterward.

As of mid-May, 287 survey replies had been received, of which 67.6% were from the United States (Table 1 ). The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a decrease in the average number of outpatient visits on weekly basis, from a mean of 44.0 to a mean of 15.1, and a decrease in the mean number of surgical procedures performed weekly, from 6.8 to 2.4.

Table 1.

Survey Responses Stratified by Employment Before and During Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic

| Variable | Employed in the United States |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 194) | No (n = 93) | ||

| Function | 194 (100.0) | 93 (100.0) | NS |

| Neurosurgeon | 183 (94.3) | 90 (96.8) | |

| Neurosurgeon in training | 9 (4.6) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Other | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Age (years) | 193 (100.0) | 93 (100.0) | NS |

| 20–29 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2.2) | |

| 30–39 | 28 (14.5) | 11 (11.8) | |

| 40–49 | 42 (21.8) | 23 (24.7) | |

| 50–59 | 65 (33.7) | 27 (29.0) | |

| >60 | 57 (29.5) | 30 (32.3) | |

| Gender | 193 (100.0) | 93 (100.0) | NS |

| Male | 171 (88.6) | 85 (91.4) | |

| Female | 22 (11.4) | 8 (8.6) | |

| Weekly visits before COVID-19 crisis (n) | 40.02 ± 26.1 | 52.2 ± 58.9 | 0.017 |

| Weekly surgical procedures before COVID-19 crisis (n) | 7.2 ± 5.6 | 6.2 ± 5.0 | NS |

| Weekly visits during COVID-19 crisis (n) | 16.2 ± 14.9 | 12.9 ± 14.1 | NS |

| Weekly surgical procedures during COVID-19 crisis (n) | 2.3 ± 2.2 | 2.5 ± 3.1 | NS |

| Self or colleagues requested for COVID-19–related guard duties (e.g., ICU, COVID-19 floor) | 34 (17.8) | 25 (27.2) | NS |

| Consulting with patients using telemedicine | NS | ||

| Respondents (n) | 181 | 90 | |

| Yes | 163 (90.1) | 73 (81.1) | |

| No | 18 (9.9) | 17 (18.8) | |

| Comfortable consulting and planning surgery using telemedicine? | 0.002 | ||

| Respondents (n) | 153 | 68 | |

| Yes | 90 (58.8) | 25 (36.8) | |

| No | 48 (32.0) | 39 (57.4) | |

| Other | 14 (9.2) | 4 (5.9%) | |

| Currently seeing patients | 164 (85.4) | 77 (83.7) | NS |

| Type of patients seen∗ | |||

| Trauma | 79 (40.7) | 29 (31.2) | |

| Infection | 68 (35.1) | 20 (21.5) | |

| Emergency | 98 (50.5) | 42 (45.2) | |

| High-grade oncology | 77 (39.7) | 38 (40.9) | |

| All patients who come | 80 (41.2) | 31 (33.3) | |

| Patient receptiveness to telemedicine | 0.012 | ||

| Respondents (n) | 153 | 67 | |

| Receptive | 124 (81.0) | 42 (62.7) | |

| Neutral | 20 (13.1) | 17 (25.4) | |

| Not receptive | 5 (3.3) | 7 (10.4) | |

| Other | 4 (2.6) | 1 (1.5) | |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

NS, not significant; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit.

Multiple answers possible.

Of the respondents, 87.1% were consulting with patients using telemedicine. For 94.6%, this represented an increase in usage compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic. The average percentage of regular consultations that had been converted to telehealth visits was 60.1%, which was greater for the respondents employed in the United States compared with that for our colleagues (66.8% vs. 47.6%; P < 0.001). Although 75.5% had estimated that their patients would be receptive to telemedicine consultations, only 52.0% of the respondents themselves were comfortable with consultations and planning surgery on the basis of such consultations. The proportions of patients receptive to and surgeons comfortable with telemedicine were higher among the respondents employed in the United States (81.0% vs. 62.7% and 58.8% vs. 36.8%, respectively).

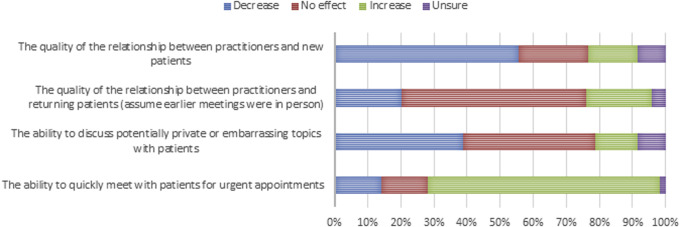

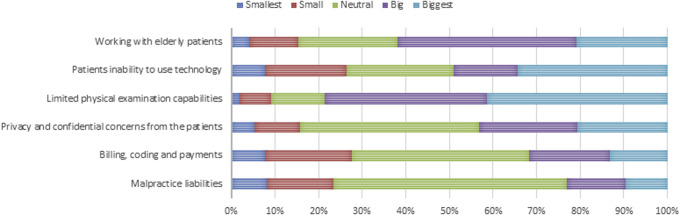

Most of the respondents believed that the use of telemedicine would decrease the quality of the relationship between themselves and new patients (55.7%). The use of telemedicine, however, would also increase their ability to quickly meet patients for urgent appointments (70.1%; Figure 1 ). The greatest difficulties encountered with the use of telemedicine included the limited capabilities of performing physical examinations (41.4%), working with the elderly (20.8%), and the privacy and confidential concerns of the patients (20.8%; Figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

Opinions on the effects of the use of telemedicine on different points.

Figure 2.

Opinions on the difficulties encountered during the use of telemedicine.

With the current COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telemedicine to conduct responsible patient care has been inevitable. However, the use of telemedicine also has its own limitations for both patients and caregivers.4 , 5 The results from our survey have shown some areas of telemedicine that should receive further attention. The first area of concern is the differences between neurosurgeons employed in the United States and neurosurgeons employed elsewhere in the world. Cultural differences and financial reasons might well explain the differences found between these 2 groups. The second area of concern is the discomfort that can accompany consulting and planning surgery through telemedicine. The discomfort might be a result of the shift toward telemedicine consultations; however, further research should focus on exploring the reasons for the discomfort among surgeons and alleviating it. Finally, an adherent disadvantage of telemedicine is the inability to perform physical examinations and the possible limited ability of the elderly to use telemedicine. Until a proper solution has been found for these last 2 categories, patients requiring a physical examination and those unable to use telemedicine should necessitate a clinical evaluation when necessary.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the respondents for answering the survey.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. A Health Telematics Policy in Support of WHO’s Health-For-All strategy for global health development: report of the WHO Group Consultation on Health Telematics, 11-16 December Geneva, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barsom E.Z., Feenstra T.M., Bemelman W.A. Coping with COVID-19: scaling up virtual care to standard practice. Nat Med. 2020;26:632–634. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greven A.C.M., Rich C.W., Malcolm J.G. Letter: neurosurgical management of spinal pathology via telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic: early experience and unique challenges. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyaa1652020 [e-pub ahead of print]. Neurosurgery. Accessed April 1, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.LoPresti M.A., McDeavitt J.T., Wade K. Letter: telemedicine in neurosurgery—a timely review. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyaa175 Neurosurgery. Accessed April 1, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Nair A.G., Gandhi R.A., Natarajan S. Effect of COVID-19 related lockdown on ophthalmic practice and patient care in India: Results of a survey. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68:725–730. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_797_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh G., Pichora-Fuller M.K., Malkowski M. A survey of the attitudes of practitioners toward teleaudiology. Int J Audiol. 2014;53:850–860. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2014.921736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ray K.N., Felmet K.A., Hamilton M.F. Clinician attitudes toward adoption of pediatric emergency telemedicine in rural hospitals. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017;33:250–257. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]