Abstract

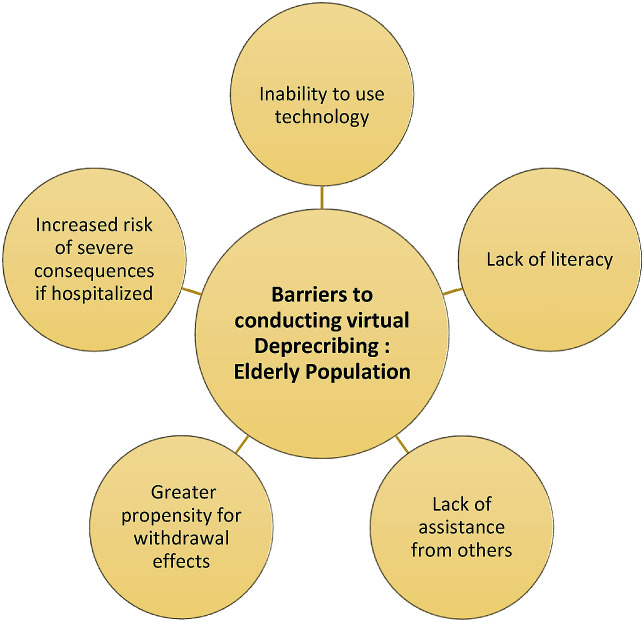

Deprescribing aims to reduce polypharmacy, especially in the elderly population, in order to maintain or improve quality of life, reduce harm from medications, and limit healthcare expenditure. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease that has led to a pandemic and has changed the lives many throughout the world. The mode of transmission of this virus is from person to person through the transfer of respiratory droplets. Therefore, non-essential healthcare services involving direct patient interactions, including deprescribing, has been on hiatus to reduce spread. Barriers to deprescribing before the pandemic include patient and system related factors, such as resistance to change, patient's knowledge deficit about deprescribing, lack of alternatives for treatment of disease, uncoordinated delivery of health services, prescriber's attitudes and/or experience, limited availability of guidelines for deprescribing, and lack of evidence on preventative therapy. Some of these barriers can be mitigated by using the following interventions:patient education, prioritization of non-pharmacological therapy, incorporation of electronic health record (EHR), continuous prescriber education, and development of research studies on deprescribing. Currently, deprescribing cannot be delivered through in person interactions, so virtual care is a reasonable alternative format. The full incorporation of EHR throughout Canada can add to the success of this strategy. However, there are several challenges of conducting deprescribing virtually in the elderly population. These challenges include, but are not limited, to their inability to use technology, lack of literacy, lack of assistance from others, greater propensity for withdrawal effects, and increased risk of severe consequences, if hospitalized. Virtual care is the future of healthcare and in order to retain the benefits of deprescribing, additional initiatives should be in place to address the challenges that elderly patients may experience in accessing deprescribing virtually. These initiatives should involve teaching elderly patients how to use technology to access health services and with technical support in place to address any concerns.

Keywords: COVID-19, Deprescribing, Elderly population, Virtual care, Drug safety

Deprescribing context

One of the definitions of polypharmacy is when an individual uses five or more medications (prescription and over-the-counter products) concomitantly creating a situation where the risks outweigh the benefits of the medications.1 , 2 Medication use in the elderly is complex due to a variety of factors: frailty, limited research representation, and physiological changes. Frailty refers to elderly people who have reduced physiologic reserve and greater stressor sensitivity. Both of these key characteristics contribute to the vulnerability of this population to medications. Trials of medications have restrictions on age and usually limit the percentage of elderly patients enrolled. Consequently, the results of the study are not representative of the elderly population and when inferred to the elderly population can lead to severe harm or lack of efficacy. Aging causes several consequences in the body, such as alteration inbody composition, organfunction and protein synthesis. Body fat increases, while muscle mass decreases leading to greater distribution and consequent increase in the exposure of some drugs. Drug clearance is impaired because of reduction in kidney and liver size as well as blood flow, which increase the half-life of medications that are eliminated by these organs. Because of the impaired liver function, the synthesis of proteins decreases including receptors, which are drug targets leading to the increase in the free drug concentration in the serum. Elderly patients have a greater sensitivity to medications due to the combination of changes resulting from aging.3 Therefore, medications require careful assessment and alterations as patients reach late adulthood. Deprescribing is a method of reducing drug dosage, changing a drug to a safer alternative, or discontinuing a drug without a specific indication or added benefit, under the supervision of a healthcare practitioner, and can be used to resolve inappropriate medication use in the elderly population.1 , 2 , 4

Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) is a recent infectious disease that attacks the human respiratory system leading to symptoms, such as fever, cough, and fatigue.5, 6, 7 The mode of transmission of this virus is person-to-person through the transfer of respiratory droplets. Therefore, social distancing and isolation of infected people protocols were implemented globally to reduce spread.7 , 8 The severity of the infection can be divided in five categories: asymptomatic, mild, moderate, severe, and critical.7Data from many countries support that the elderly population has the greatest risk of mortality from COVID-19, but all ages have been infected.7 As a result of COVID-19, non-essential services that involve direct patient interactions including deprescribing has been on hold in Canada in an effort to contain the outbreak.

There are several benefits to deprescribing: maintains or improves the quality of life of patients, reduces harm from medications in patients, and reduces healthcare expenditure.1 , 2

Delirium, syncope and falls are some examples of medication related harm which can lead to hospitalization of elderly patients.9 Canadian health care system spends roughly $419 million on inappropriate medication use and $1.4 billion on negating the harm incurred from inappropriate medication use.1 According to Canadian Institute for Health Information, about one third of the elderly population of Canada were taking five or more different classes of medications chronically in 2016, which is a significant portion of the population that could benefit from deprescribing.10 A recent study that evaluated the financial impact of 8 different deprescribing scenarios on a typical patient case across different provinces in Canada showed that deprescribing can save money for the patient (0.03%–87.4%) and government (0.38%–15.77%).4

There are several deprescribing initiatives in place in different provinces in Canada, such as UBC Pharmacists Clinic in British Columbia, Prairie Mountain Health Sedative Describing Initiative in Manitoba, Medication Therapy Services Clinic in Newfoundland and Labrador, Winchester District Memorial Hospital Describing Program in Ontario, and Agir pour mieux dormir program in Quebec.10 The partnership between patients, caregivers, and healthcare practitioners is instrumental to the success of deprescribing and due to COVID-19, these interactions have been interrupted.2 COVID-19 can lead to severe complications in the elderly population and individuals with existing comorbidities.5 Therefore, reducing the medication burden and having an uptodate medication list is very important in the case that these patients get infected with the virus and require hospitalization. There were several barriers to conducting deprescribing prior to COVID-19, but the pandemic has led to additional challenges that further impede the momentum of deprescribing initiatives.

Deprescribing barriers prior to COVID-19

Barriers to deprescribing in the elderly population before COVID-19 can be divided into two categories: patient and system. Patient-related barriers include resistance to change (due to concerns about experiencing withdrawal effects or symptoms of disease), knowledge deficit about deprescribing, and lack of alternatives for treatment of disease. 11, 12, 13 All of these barriers can be addressed by educating the patient on the purpose and process of deprescribing. The patient needs to be aware that there is no reason to continue a medication that is not beneficial and/or may be contributing to side effects. A study conducted elderly Canadians living in the community on their attitude on deprescribing demonstrated approximately 50% of participants would like to lessen their medication load.14 On the other hand other, research evaluating the willingness of residents of senior homes for deprescribing has shown that 78.9% of them were prepared to make changes to their medications with positive reinforcement from their doctor.15 Consequently, setting some time to address the patient's concerns before beginning the process of deprescribing and checking up on how the patient is feeling throughout the process can help ensure that this intervention remains successful. In terms of the lack of alternatives, non-pharmacological interventions, which do not have side effects, can be prioritized in specific conditions, such as insomnia.12 For example, a study conducted on patient engagement during deprescribing showed that when resources are combined with nonpharmacological advice, deprescribing initiatives were more successful.16

System-related factors include uncoordinated delivery of health services, prescribers'attitudes and/or experience, limited availability of guidelines for deprescribing, lack of evidence on preventative therapy.11 , 12 , 17 , 18 Healthcare in Canada is delivered provincially, and each province has their own procedures in place. However, a commonality within the provinces is that care is given in isolation depending on levels of care (primary care, secondary care, tertiary care, and quaternary care) and communication gaps exist between healthcare practitioners. This discrepancy is because of the absence of an electronic health record (EHR), which would consist of a complete record of a patient's health history. All healthcare practitioners and patients would have access to HER, leading to more collaboration and consequently better medication choices and deprescribing efforts. Many provinces are in transition to EHR under Canada Health Infoway (CHI) within the last couple of years, which can help overcome these challenges.19 Moreover, healthcare practitioners must continuously learn about new practices, such as deprescribing to be able to provide optimal evidence-based medicine.12 , 13 Therefore, it is important to teach deprescribing in the curriculum of healthcare practitioners as well as offer it as a topic of importance in continuing education for practising healthcare practitioners.12 , 13 Prescribing guidelines exist, but for a number of reasons, there is difficult with healthcare practitioners implementing them in practice.20 , 21 The applicability of the available guidelines for deprescribing was tested by a recent study. The results showed that 46.7% of discharged elderly patients from a hospital used medications within deprescribing guidelines and 34% of patients fit the requirements for deprescribing.22 Another study evaluating the deprescribing self-efficacy of health care practitioners (physicians, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists) before and after being given 3 different algorithms has shown that significant increases in self-efficacy scores across classes of medications studied in the development and implementation of a deprescribing plan.23

Canada has been slowly increasing access to evidence-based deprescribing guidelines through the deprescribing network and more guideline are expected to be available in the near future to ease the application of deprescribing. As deprescribing becomes more prevalent due to the incorporation of EHR, researchers would have more opportunities to evaluate the benefits of deprescribing. Thus, we can infer that more healthcare practitioners would be willing to incorporate deprescribing into their daily practices when there is abundance of evidence supporting the effectiveness of deprescribing.

Deprescribing barriers due to COVID-19

COVID-19 has led additional barriers to deprescribing. Because non-essential in-person interactions have been on hold, healthcare has adapted to providing these services electronically through video conferencing and telephone. Video conferencing can better mimic the in-person experience allowing healthcare practitioners to conduct some of their visual assessments. As mentioned previously, the EHR is important in order to overcome barriers in deprescribing, but in the current situation the importance has been amplified. In response to the current situation the transition to EHR has been accelerated as CHI and Health Canada have joined forces to provide faster and greater access to virtual care to Canadians.24

The virtual delivery of deprescribing has challenges in the elderly for a variety of reasons: inability to use technology, lack of resources (e.g. video camera, smartphone), lack of literacy, lack of assistance from others, greater propensity for withdrawal effects, and greater risk for hospitalization (refer to Fig. 1 ). Most elderly patients are not able to navigate technology as efficiently as the younger population, so delivering deprescribing services in this manner can be difficult. Moreover, elderly patients with psychological conditions, such as Alzheimer's disease and dementia or physical conditions, such as arthritis or Parkinson's disease will be further disadvantaged due to their mental and/or physical limitations. Another factor is literacy, as some elderly patients have reduced literacy relative to younger patients. Using technology to delivery healthcare services requires patients to be able to read or write as well as speak and those without sufficient literacy cannot communicate their thoughts. Elderly patients that live with family members could seek assistance on how to use technology. Nonetheless, according to Statistics Canada approximately 25% of seniors lived alone in 2011, which is substantial number of elderly patients.25 Due to social distancing and isolation protocol, they would not be receiving help from family members in navigating these services, which further exacerbates the challenges. Income is also an important factor, because elderly patients would need access to a smartphone or computer with a webcam that allows them to connect to these services. If elderly patients do not have an electronic device already, then having to purchase one and the associated data/internet plans area significant cost during this crucial time.

Fig. 1.

Barriers to conducting Virtual Deprescribing in the Elderly Population.

Moreover, the environment should be quiet for elderly patients to have uninterrupted assessments during the virtual interaction. Connection problems are also an issue with technology, so repetition is important to verify that the content of the discussion has been interpreted carefully. Elderly patients' lives have already been drastically altered by the pandemic, so they may be less receptive to making more changes in their lives. Therefore, healthcare practitioners may have difficult time initiating a conversation about making changes to medication that they have been taking for many years. Another issue is that during the pandemic, elderly patients’ lives have been changed and initiating a conversation about making changes to medication that they have been using for many years might be difficult. Due to isolation, their conditions could be exacerbated, such as insomnia and anxiety. Therefore, instructing these patients to discontinue certain medication – like benzodiazepines and anti-psychotics – can cause them to experience withdrawal symptoms. Furthermore, if they do experience severe withdrawal symptoms, admitting them to a hospital would put them at greater risk of acquiring COVID-19 and negatively impacting their health.

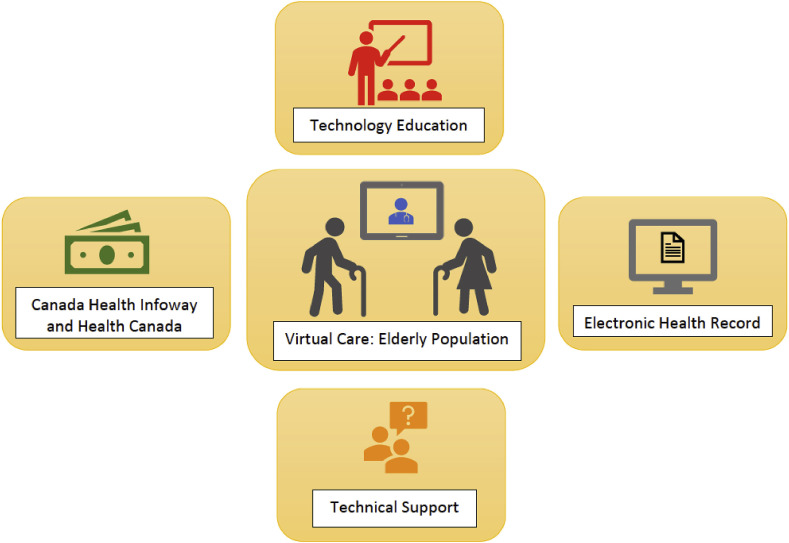

Although the pandemic may be a temporary situation, virtual care is the future of health care. Consequently, steps need to be taken to make sure that the elderly population is well equipped for the future (Refer to Fig. 2 ). Libraries and community centres should have the required technology and private room in place to allow for seniors to access health services electronically. These locations should have classes to teach elderly patients on how to navigate electronic health services with technical support available to help troubleshoot any difficulties. One example of an initiative that aims to help seniors is through a non-profit association in Ottawa called Connected Canadians. This organization helps the elderly population use technology in order to connect with their families during the pandemic.26 These types of initiatives aimed at increasing connectivity to healthcare practitioners should be encouraged all over Canada.

Fig. 2.

Key components of virtual care in the elderly population.

Conclusion

Deprescribing is a valuable service that will help the elderly population better manage their medications as well as benefit the Canadian healthcare system financially. Barriers to deprescribing before COVID-19, such as resistance to change, knowledge deficit about deprescribing, and lack of alternatives for treatment of disease, uncoordinated delivery of health services, prescribers’ attitudes and/or experience, limited availability of guidelines for deprescribing, and lack of evidence on preventative therapy need to be managed through different interventions. Some examples of these interventions include patient education, prioritization of non-pharmacological therapy, incorporation of the EHR continuous prescriber education, and development of research studies. Barriers due to COVID-19 from the lack of direct patient interaction can collectively be addressed through increased access to the EHR and virtual care, which has been expeditated by Health Canada and Canada Health Infoway. Nonetheless, there is a necessity to manage some of the challenges that elderly patients have with using virtual care, such as inability to use technology, lack of literacy, lack of assistance from others, greater propensity for withdrawal effects, and increased risk after hospitalization. Some of these issues can be resolved by encouraging policy makers to allow technological access to the elderly through community centres and libraries. Virtual care is the future of health care and we should take the necessary steps to make sure that seniors are not left behind as we renovate healthcare.

Author's contribution

Ali Elbeddini (primary and corresponding author): Original Manuscript preparation, Conceptualization, Data curation, Analysis of the paper, Literature search, Data collection, Writing, Reviewing and Editing, Driving for the ideas and thoughts. Thulasika Prabaharan: Original Manuscript preparation, Analysis of the paper, Literature search, Data collection, curation, Writing, Reviewing and Editing, Driving for the ideas and thoughts. Sarah Almasalkhi: Original Manuscript preparation, Analysis of the paper, Literature search, Data collection, Writing, Reviewing and Editing, Driving for the ideas and thoughts. Cindy Tran: Original Manuscript preparation, Analysis of the paper, Literature search, Data collection, Writing, Reviewing and Editing, Driving for the ideas and thoughts. Yueyang Zhou: Original Manuscript preparation, Analysis of the paper, Literature search, Data collection, Writing, Reviewing and Editing.

Declaration of competing interest

No known competing interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the support from the pharmacy team in facilitating the data collection.

References

- 1.Deprescribing: managing medications to reduce polypharmacy. https://www.ismp-canada.org/download/safetyBulletins/2018/ISMPCSB2018-03-Deprescribing.pdf [Internet]. Ismp-canada.org. 2020. Available from:

- 2.What is deprescribing? — do I still need this medication? Is deprescribing for you? 2020. https://www.deprescribingnetwork.ca/deprescribing [Internet]. deprescribingnetwork.ca, Available from:

- 3.Page A., Potter K., Clifford R., Etherton-Beer C. 2016. Deprescribing in Older People.https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/27451330/?from_term=Deprescribing+in+older+people&from_filter=ds1.y_10&from_pos=1 Maturitas [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu Fadaleh S., Shkrobot J., Makhinova T., Eurich D., Sadowski C. Financial advantage or barrier when deprescribing for seniors: a case based analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Q&A on coronaviruses (COVID-19) https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses [Internet]. Who.int. 2020 [cited 10 May 2020]. Available from:

- 6.Rothan H., Byrareddy S. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/pmc/articles/PMC7127067/ [Internet]. [cited 12 May 2020] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulut C., Kato Y. Epidemiology of COVID-19. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50(3):563–566. doi: 10.3906/sag-2004-172. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/pmc/articles/PMC7195982/ [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drug Use Among Seniors in Canada. Canadian Institute for Health Information; Ottawa: 2016. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/drug-use-among-seniors-2016-en-web.pdf [Internet] 2020. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dharmarajan T., Choi H., Hossain N. Deprescribing as a clinical improvement focus. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.031. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/31672564/?from_term=Deprescribing+as+a+Clinical+Improvement+Focus&from_filter=ds1.y_10&from_pos=1 [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deprescribing initiatives in Canada. https://www.deprescribingnetwork.ca/deprescribing-initiatives [Internet]. deprescribingnetwork.ca. 2020 [cited 10 May 2020]. Available from:

- 11.Kuntz J. Barriers and facilitators to the deprescribing of nonbenzodiazepine sedative medications among older adults. Perm J. 2018;22:17–157. doi: 10.7812/TPP/17-157. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5922966/ [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zechmann S., Trueb C., Valeri F., Streit S., Senn O., Neuner-Jehle S. Barriers and enablers for deprescribing among older, multimorbid patients with polypharmacy: an explorative study from Switzerland. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s12875-019-0953-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillespie R., Harrison L., Mullan J. Deprescribing medications for older adults in the primary care context: a mixed studies review. Health Sci Rep. 2018;1(7):e45. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.45. https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/pmc/articles/PMC6266366/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sirois C., Ouellet N., Reeve E. Community-dwelling older people's attitudes towards deprescribing in Canada. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2017;13(4):864–870. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalogianis M., Wimmer B., Turner J. Are residents of aged care facilities willing to have their medications deprescribed? Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12(5):784–788. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trenaman S., Willison M., Robinson B., Andrew M. A collaborative intervention for deprescribing: the role of stakeholder and patient engagement. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;16(4):595–598. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Avanzo B., Agosti P., Reeve E. Views of medical practitioners about deprescribing in older adults: findings from an Italian qualitative study. Maturitas. 2020;134:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Djatche L., Lee S., Singer D., Hegarty S., Lombardi M., Maio V. How confident are physicians in deprescribing for the elderly and what barriers prevent deprescribing? J Clin Pharm Therapeut. 2018;43(4):550–555. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Progress in Canada. 2020. https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/en/what-we-do/progress-in-canada Infoway-inforoute.ca. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conklin J., Farrell B., Suleman S. Implementing deprescribing guidelines into frontline practice: barriers and facilitators. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(6) doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.08.012. 796-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moriarity F., Pottie K., Dolovih L., McCarthy L. Deprescribing recommendations: an essential consideration for clinical guidelines developers. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(6):806–810. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bredhold B., Deodhar K., Davis C., DiRenzo B., Isaacs A., Campbell N. Deprescribing opportunities for elderly inpatients in an academic, safety-net health system. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrell B., Richardson L., Raman-Wilms L., de Launay D., Alsabbagh M., Conklin J. Self-efficacy for deprescribing: a survey for health care professionals using evidence-based deprescribing guidelines. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rapid response to COVID-19. 2020. https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/en/solutions/rapid-response-to-covid-19 Infoway-inforoute.ca, Available from:

- 25.Living arrangements of seniors. 2018. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/98-312-x/98-312-x2011003_4-eng.cfm 12.statcan.gc.ca, Available from:

- 26.Szperling P. Ottawa non-profit organization helps seniors connect during COVID pandemic. 2020. https://ottawa.ctvnews.ca/ottawa-non-profit-organization-helps-seniors-connect-during-covid-pandemic-1.4901192 Ottawa.ctvnews.ca, Available from: