Abstract

The novel coronavirus strain known as SARS-CoV-2 has rapidly spread around the world creating distinct challenges to the healthcare workforce. Coagulopathy contributing to significant morbidity in critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 has now been well documented. We discuss two cases selected from patients requiring critical care in April 2020 in New York City with a unique clinical course. Both cases reveal significant thrombotic events noted on imaging during their hospital course. Obtaining serial inflammatory markers in conjunction with anti-phospholipid antibody testing revealed clinically significant Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). This case series reviews the details preceding APS observed in SARS-CoV-2 and aims to report findings that could potentially further our understanding of the disease.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Covid-19, Antiphospholipid syndrome, Anticardiolipin, Coagulopathy, Critical care, ICU, Coronarvirus, Stroke, Peripheral arterial disease, Infarct

1. Introduction

In December 2019, China reported a number of pneumonia cases diagnosed in the Hubei province later identified as SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Critically ill patients with this disease have been well-documented to present with respiratory failure in the most severe of cases. Notably patients have also presented with manifestations of venous and arterial thrombotic events. As reported in an observational study conducted in two intensive care units in the Netherlands, patients testing positive for COVID-19 were found to have a 31% incidence of thrombotic events which authors concluded to be remarkably high [1].

The cases described in the following series describe patients with COVID-19 presenting with thrombotic events potentially caused by the disease. The mechanism by which COVID-19 may cause thrombotic events is theorized to be associated with immobilization, hypoxia, or disseminated coagulopathy [1]. Both patients in this case series were found to have elevated levels of anticardiolipin antibodies which may be indicative of a key association between this novel virus and an acquired coagulopathy.

2. Case 1

A 29 years-old female with a past medical history of hemoglobin S—C disease presented to the Emergency Department with chief complaints of vomiting and abdominal pain. She reported associated subjective fevers that began eight days prior to presentation along with a non-productive cough and generalized myalgia. A nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 was found to be positive from two days prior. Patient denied any known sick contacts in her family but believed she may have been exposed to sick individuals at her place of work.

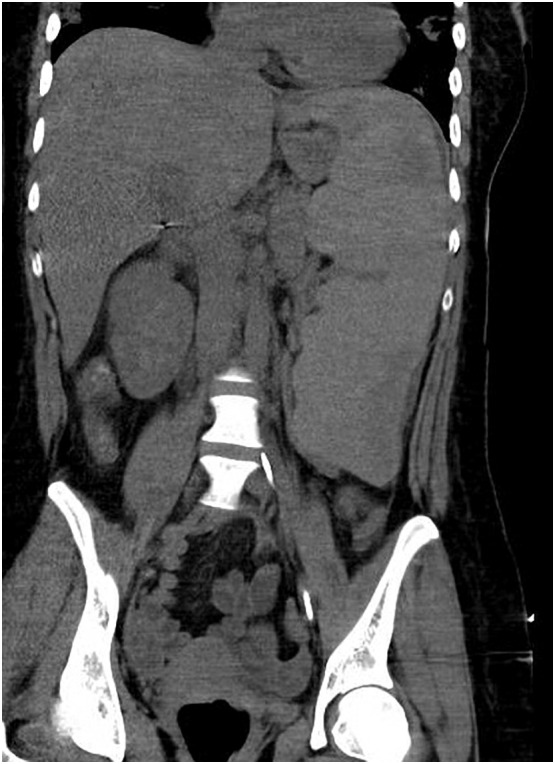

Vital signs on presentation were significant for an elevated temperature of 103.4 F, heart rate 124, blood pressure 97/51, and 99% oxygen saturation on room air. Physical exam was notable for bibasilar crackles but otherwise unremarkable. Initial lab-work demonstrated leukopenia with predominant lymphopenia and a normocytic anemia (Table 1 ). A chest x-ray was obtained and revealed the presence of patchy consolidations in bilateral lower lobes. CT chest/abdomen/pelvis (Fig. 1 ) was notable for diffuse ground-glass opacities in the periphery of bilateral lungs as well as splenomegaly with a splenic hypodensity measuring 8.6 × 0.7 cm and surrounding peri-splenic edema, consistent with a splenic infarct. Hydroxychloroquine and a one-time dose of Tocilizumab were administered along with supportive measures. A continuous heparin infusion was also initiated and patient was admitted to the general medical ward for further workup.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the two patients admitted for COVID-19 pneumonia.

| Characteristics |

Case 1 | Case 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 29 | 58 | |

| Sex | Female | Male | |

| Medical History | Sickle cell trait | Dyslipidemia | |

| Symptoms at disease onset | Fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, cough, myalgias | Shortness of breath, cough | |

| CXR Imaging Features | Bilateral airspace opacities. | Bilateral opacities | |

| Days from disease onset to thrombotic event | 8 | 15 | |

| Findings on Admission to ICU | Lethargy, fever | Tachypneia, tachycardia and desaturation to 80% SpO2 | |

| Days since disease onset | 10 | 19 | |

| Laboratory findings | [Reference range] | ||

| WBC (k/uL) | 4.80–10.8 | 21,130 | 20,006 |

| Total Neutrophils (k/uL) | 1.40–6.50 | 17,150 | 14,290 |

| Total Lymphocytes (k/uL) | 1.20–3.40 | 1280 | 309 |

| Total Monocytes (k/uL) | 0.10–0.60 | 1830 | 177 |

| Platelet Count (k/uL) | 130–400 | 191 | 385 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.0–18.0 | 11.2 | 18.5 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.50–5.20 | 3.4 | 3.5 |

| Alanine Aminotransferase (U/L) | 0–41 | 30 | 189 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase (U/L) | 0–41 | 129 | 121 |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase, serum (U/L) | 50–242 | >2500 | 634 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7–1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Creatinine Kinase (U/L) | 0–225 | 288 | 2138 |

| EGFR (mL/min/1.73 M2) | >60 | 86 | 98 |

| Prothrombin time (sec) | 9.95–12.87 | 14.1 | 12.7 |

| Activated Partial-Thromboplastin Time (sec) | 27.0–39.2 | 28 | 38.9 |

| Fibrinogen Assay (mg/dL) | 204.4–570.6 | 504 | 312 |

| D Dimer (ng/mL) | 0–230 | 2822 | 3012 |

| Serum Ferritin (ng/mL) | 30–400 | 4511 | 1504 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.02–0.10 | 7.41 | 0.08 |

| High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (mg/dL) | 0.00–0.40 | 25.35 | 18.4 |

| AntiCardiolipin IgM (MPL) | 0.00–12.5 | 20.4 | 34.2 |

| AntiCardiolipin IgG (GPL) | 0.00–12.5 | 14.8 | 44.7 |

| Imaging Features | Bilateral cerebral infarcts in left temporoparietal and right parietal cortical region. Splenic infarct. | Left mid peroneal artery and distal left anterior tibial artery occlusions |

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography abdomen and pelvis with contrast showing splenic hypodensities with surrounding peri-splenic edema. Findings consistent with splenic infarction.

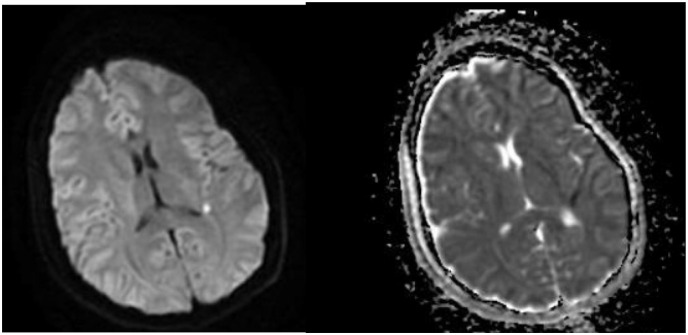

On hospital day one, patient was found to be lethargic with an altered mental status. CT head revealed signs of early cerebral edema. Follow-up MRI brain (Fig. 2 ) showed a small acute infarct in the left temporo-parietal peri-ventricular white matter with a high medial right parietal cortical infarct.

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast showing restricted diffusion in the peri-ventricular left temporoparietal white matter consistent with acute infarct. Additional focus of restricted diffusion in the high medial right parietal cortex suggesting infarct. Corresponding areas of hypodensity are demonstrated on ADC (right image).

She was later intubated for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure on hospital day three. Serial inflammatory markers were trended with worsening D-dimer and LDH noted at time of respiratory failure. Hyper-coagulable workup was significant for positive anti-cardiolipin IgM and anti-cardiolipin IgG phospholipid antibodies (Table 1). The remaining workup was found to be unremarkable including: Anti-thrombin III, Homocysteine level, Beta-2-glycoprotein 1 antibody, Protein C resistance, Factor V Leiden, MTHFR gene, and Calreticulin gene expression.

3. Case 2

A 58 years-old male with past medical history of dyslipidemia presented to the emergency department with a chief complaint of shortness of breath associated with subjective fevers and a mild non-productive cough that started twelve days prior to presentation. He was initially afebrile and normotensive with sinus tachycardia to 105 beats per minute. Chest x-ray revealed patchy bilateral interstitial infiltrates. A COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab obtained that day returned positive and a regimen of Hydroxychloroquine and Azithromycin was initiated.

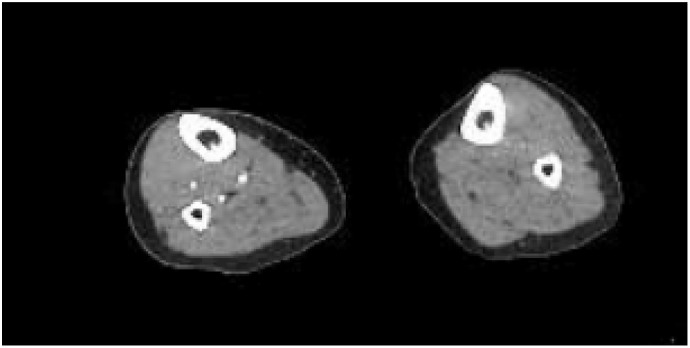

Oxygen requirements increased during early hospitalization but patient never required intubation during his stay. An interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, Anakinra, was started on hospital day six. Later that day he was noted to have a cold left lower extremity in comparison to the right with mild pallor and cyanosis spanning from the plantar arch to the ankle with absent dorsalis pedis and posterior tibialis pulses. Therapeutic anti-coagulation with lower molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was initiated due to concern for early acute peripheral artery disease. An arterial doppler study performed showed no evidence of significant arterial occlusive disease in that extremity. However, computed tomography with angiography (Fig. 3 ) of the left lower extremity showed absent flow distal to the left posterior tibial artery, as well as occlusion of the left mid-peroneal artery and distal left anterior tibial artery. No vascular surgical intervention was performed and the LMWH was continued.

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography with angiography of the right and left lower extremity with left extremity showing no flow in the left posterior tibial artery near the left ankle suggesting complete occlusive disease.

Serial inflammatory markers were obtained during hospitalization (Table 1). A hyper-coagulable workup revealed positive anti-cardiolipin IgM and anti-cardiolipin IgG phospholipid antibodies, raising suspicion for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). Beta-2-glycoprotein-1-antibody, JAK-2, and Calreticulin gene abnormal expression screens were negative.

4. Discussion

Since the onset of the novel coronavirus infection (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019, it has spread extensively worldwide resulting in significant mortality in multiple countries [2]. While the majority of critically ill patients initially present with respiratory failure, a sizeable portion progress to multi-organ failure with the development of coagulopathy seen as an especially pertinent prognostic factor. In a recent report by Tang et al., coagulopathy exhibited by significantly elevated D-dimer, fibrin degradation products, and longer prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times was described in non-survivors versus survivors (p < .05). Furthermore, 71.4% of non-survivors met the criteria for disseminated intravascular coagulation during their hospital stay vs 0.6% of survivors [3]. As guidelines continue to develop concerning coagulopathies in SARS-CoV-2 patients, some current recommendations suggest starting prophylactic anticoagulation in all patients requiring hospitalization in the absence of any contraindication 1.

APS generally describes venous and/or arterial thrombosis with the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs). Catastrophic APS represents the most severe form of the disease, and is associated with multiorgan failure resulting from microvascular thrombosis. While anticoagulation continues to be the mainstay of therapy, there remains a high risk of recurrent thrombosis and bleeding complications [4].

Only three case of SARS-CoV-2 patients also developing clinically significant APS have been previously reported [5]. These cases were seen in Tongji Hospital in Wuhan, China and demonstrated multiple cerebral infarcts discovered on brain imaging. The cases presented in this series demonstrate clinically significant APS manifesting as multiple cerebral and splenic infarcts in case 1, and peripheral arterial disease in case 2. There have been many different proposed etiologies to developing coagulopathy with SARS-CoV-2. According to Harzallah et al., there is also a high incidence of lupus anticoagulant in patients that were positive for Covid-19, however none of them had any reported thrombotic events [8].

It is worth noting there is an established association between elevated aPL antibodies and sepsis secondary to viral illness, most commonly in hepatitis C, Ebstein Barr virus, Human immunodeficiency virus, Cytomegalovirus, and Leprosy [6]. Despite the positive titers of anti-β2-glycoprotein and anti-cardiolipin antibodies, these are typically not associated with clinical manifestations such as thrombosis [7].

We believe our cases to be clinically relevant as they represent a new form of coagulopathy in SARS-CoV-2 patients. Further understanding of the complications associated with the disease can help our comprehension of the pathophysiology of the disease. While it remains unclear if the development of anticardiolipin antibodies represents a response to the septic phase of the disease or a true manifestation of APS, the thrombotic events presented in our cases are concerning for the latter. Further clinical studies are warranted to explore the coagulopathy patterns in these patients to improve our knowledge on the clinical course of the disease.

References

- 1.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;0(0) doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim W. Antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:675–680. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(17):238. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asherson R.A., Cervera R. Antiphospholipid antibodies and infections. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(5):388–393. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warkentin T.E., Aird W.C., Rand J.H. Platelet-endothelial interactions: sepsis, HIT, and antiphospholipid syndrome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2003:497–519. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2003.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harzallah I., Debliquis A., Drénou B. Lupus anticoagulant is frequent in patients with Covid-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14867. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]