Abstract

Young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) look less toward faces compared to their non-ASD peers, limiting access to social learning. Currently, no technologies directly target these core social attention difficulties. This study examines the feasibility of automated gaze modification training for improving attention to faces in 3-year-olds with ASD. Using free-viewing data from typically developing (TD) controls (n = 41), we implemented gaze-contingent adaptive cueing to redirect children with ASD toward normative looking patterns during viewing of videos of an actress. Children with ASD were randomly assigned to either (a) an adaptive Cue condition (Cue, n = 16) or (b) a No-Cue condition (No-Cue, n = 19). Performance was examined at baseline, during training, and post-training, and contrasted with TD controls (n = 23). Proportion of time looking at the screen (%Screen) and at actresses’ faces (%Face) was analyzed. At Pre-Training, Cue and No-Cue groups did not differ in %Face (P > 0.1). At Post-Training, the Cue group had higher %Face than the No-Cue group (P = 0.015). In the No-Cue group %Face decreased Pre- to Post-Training; no decline was observed in the Cue group. These results suggest gaze-contingent training effectively mitigated decreases of attention toward the face of onscreen social characters in ASD. Additionally, larger training effects were observed in children with lower nonverbal ability, suggesting a gaze-contingent approach may be particularly relevant for children with greater cognitive impairment. This work represents development toward new social attention therapeutic systems that could augment current behavioral interventions.

Keywords: attention, children, data-driven techniques, developmental psychology, eye movement, intervention early, visual

Lay Summary:

In this study, we leverage a new technology that combines eye tracking and automatic computer programs to help very young children with ASD look at social information in a more prototypical way. In a randomized controlled trial, we show that the use of this technology prevents the diminishing attention toward social information normally seen in children with ASD over the course of a single experimental session. This work represents development toward new social attention therapeutic systems that could augment current behavioral interventions.

Introduction

Attention to the social cues of others, such as facial expression, eye gaze, gestures, and language, is a critical foundation for a number of developmental skills, facilitating learning through modeling and imitation [Abravanel, Levan-Goldschmidt, & Stevenson, 1976; Carpenter, 2006; Heyes, 2001; Meltzoff & Moore, 1977; Tomasello, 1996; Want & Harris, 2002]. In addition, attention to social cues impacts the development of social-cognitive skills such as joint attention, social play, comprehension of intentions and goals, language development, and theory of mind [Bakeman & Adamson, 1984; Carpenter, Nagell, & Tomasello, 1998; Charman et al., 2000; Moore & Dunham, 1995]. Many of the skills that depend on attention to social cues represent critical milestones in typical development. These skills are also often impaired in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and include difficulties in reciprocal social exchanges [Wetherby et al., 2004], joint attention [Bono, Daley, & Sigman, 2004; Bruinsma, Koegel, & Koegel, 2004; Charman et al., 1997; Dawson et al., 2004; Hecke et al., 2007; Leekam & Ramsden, 2006; Mundy & Vaughan, 2002; Sullivan et al., 2007], and imitation [Charman et al., 1997; Colombi et al., 2009; Rogers, Hepburn, Stackhouse, & Wehner, 2003; Rogers & Williams, 2006; Vivanti, Nadig, Ozonoff, & Rogers, 2008; Williams, Whiten, & Singh, 2004].

The typical developmental course of social attention begins at birth when newborns show visual preference for faces and early infant play is dominated by attention to the caregiver’s face [Bakeman & Adamson, 1984; Goren, Sarty, & Wu, 1975; Johnson, Dziurawiec, Ellis, & Morton, 1991]. In eye-tracking studies, typically developing (TD) infants show an increase in their preference for faces while observing a social scene between 3 and 9 months of age [Frank, Vul, & Johnson, 2009]. While faces continue to capture the majority of attention for TD toddlers from 9 to 30 months during eye-tracking tasks, an increasing amount time is spent attending to specific socially informative locations, for example, the mouths and hands, which provide information about emotional expression, language, and goal directed action [Frank, Vul, & Saxe, 2012]. This work suggests that early attention to faces may provide a necessary learning context for effective social attention in toddlerhood, which is context-dependent and driven by a variety of increasingly sophisticated social cues.

Individuals with ASD display atypical patterns of social attention compared to their TD peers in the infant and toddler years, characterized by diminished looking toward faces, people, and relevant social cues. These atypical patterns of social attention have been associated with poorer developmental outcomes. In infants at risk for developing autism, increased attention toward faces from 3- to 12-months of age is prospectively associated with fewer social deficits and joint attention skills [Tsang, Shic, Nguyen, Zolfaghari, & Johnson, 2015]. Later in life, at age 2, toddlers with ASD show less looking at the face of an actress emulating a prototypical bid for dyadic engagement, with reduced looking to the actress’ face associated with atypical language development [Chawarska, Macari, & Shic, 2012] and increased social deficits [Jones, Carr, & Klin, 2008]. Similarly, toddlers with ASD show limited attention to others when viewing a naturalistic play scene, with this limited attention correlated with cognitive deficits and ASD severity [Shic, Bradshaw, Klin, Scassellati, & Chawarska, 2011]. Campbell, Shic, Macari, and Chawarska [2014] have shown that subgroups of toddlers with ASD who looked at faces longer had better social and language outcomes compared to those who spent less time looking at faces. These studies suggest that attention to faces may be important for the development of language in toddlers with ASD.

Decreased attention and its association with developmental outcomes in ASD is likely due to a bi-directional process: it reflects not only the culmination of atypical experience-dependent knowledge regarding scenes and people, but also suggests that future access to observational learning may be limited, leading to cascading impairments across other aspects of development [Jones et al., 2008; Karmiloff-Smith, 2007; Klin, Jones, Schultz, & Volkmar, 2003]. Recent research has shown that increases in language skills as a result of behavioral intervention for young children with ASD is correlated with changes in face scanning [Bradshaw et al., 2019]. Conversely, it is important to understand how shaping attention may mitigate the compounding effects of atypical social experiences [Dawson, 2008]. For this reason, there exists a need to develop efficient, accessible tools for shaping attentional strategies that may serve to help redirect the social trajectory of autism.

Improving early social attention in naturalistic, interactive contexts can have wide ranging effects on learning, social skills, and social impairments [Webb, Neuhaus, & Faja, 2017]. Building on the developmental literature, many behavioral interventions incorporate strategies for improving social attention as a stepping-stone to promoting language and social skills in children with ASD [Paul, 2008; Reichow & Fr, 2010; Rogers, 2000]. Naturalistic, developmental, behavioral interventions capitalize on our knowledge of typical development and strive to teach skills in a typical developmental sequence, beginning with increasing social attention and social engagement, which leads to increased learning opportunities and results in gains in developmental skills [Schreibman et al., 2015]. Some of these interventions explicitly target increasing attention to the face of the clinician or caregiver [Dawson et al., 2010; Schertz & Odom, 2007]. Behavioral interventions typically require extensive involvement by a specialized treatment team, including a doctoral-level clinical supervisor, multiple trained clinicians, and parents. However, because these methods can be intensive, costly, and difficult to access for many children in need, researchers have begun investigating the possibility of providing or augmenting interventions with computer programs [Schultheis & Aa, 2001] in order to increase the availability of individualized intervention programs. For example, the FaceSay program uses a traditional PC video game structure to teach face-processing skills to individuals with ASD [Hopkins et al., 2011; Rice, Wall, Fogel, & Shic, 2015]. Unfortunately, the standard PC-based game approach may not be feasible in very young children and individuals with more significant cognitive impairments due to limitations in manual dexterity necessary for hand-held controls or the language skills needed for understanding complex instructions.

An attractive alternative to more demanding intervention delivery systems relies on the use of gaze-contingent eye tracking (GCET). GCET uses participant eye movements to trigger events on the screen, allowing participants to interact using just their eyes. This approach leverages the accuracy and early maturity of the oculomotor system [Bertenthal, 1996], whereby the eye is used for both responding to the environment and receiving feedback. GCET has grown in prominence in scientific research due to its ability to provide real-time feedback based on looking behaviors in various domains including, for example, studies of brain activity during interactive gaze-dependent social tasks [Oberwelland et al., 2016; Schilbach, 2014; Timmermans & Schilbach, 2014; Wilms et al., 2010]. In autism research, GCET has been used to identify between-group differences for holistic face processing [Evers, Van Belle, Steyaert, Noens, & Wagemans, 2017] and to examine how variability of naturalistic social interactions contributes to social learning difficulties [Vernetti, Smith, & Senju, 2017]. In addition, experiments with virtual avatars and gaze-contingent environments have been developed with potential therapeutic relevance to children with ASD [Bekele et al., 2014; Lahiri, Bekele, Dohrmann, Warren, & Sarkar, 2013; Lahiri, Warren, & Sarkar, 2011; Trepagnier, 2006; Trepagnier et al., 2006]. Other work designed for eventual therapeutic potential has tested gaze-contingent social viewing windows [Courgeon, Rautureau, Martin, & Grynszpan, 2014; Grynszpan et al., 2009; Grynszpan, Simonin, Martin, & Nadel, 2012] and explored gaze-contingent executive function training [Wass, Porayska-Pomsta, & Johnson, 2011]; however, these projects have not explicitly involved individuals with ASD.

Despite the emergence of GCET as a potential therapeutic tool, no efforts to use this technology with very young children with ASD viewing naturalistic scenes have yet been reported. Behavioral interventions for infants and toddlers with ASD use behavioral principles and reinforcement to improve social attention [Bradshaw, Koegel, & Koegel, 2017; Bradshaw, Steiner, Gengoux, & Koegel, 2015]. Similarly, GCET can use dynamic modification of a visual display to encourage attention to socially relevant aspects of a scene. In particular, work noting perceptual irregularities in ASD offers some insight into the potential for gaze-contingent techniques as an intervention. Studies have shown that individuals with ASD are more sensitive to simple luminance-defined contrast [Bertone, Mottron, Jelenic, & Faubert, 2003, 2005; Mottron, Dawson, Soulieres, Hubert, & Burack, 2006] and may exhibit difficulties processing certain types of motion [Bertone et al., 2003; Blair, Frith, Smith, Abell, & Cipolotti, 2002; Blake, Turner, Smoski, Pozdol, & Stone, 2003; Milne et al., 2002; Spencer et al., 2000]. Thus, it may be possible to guide attention in ASD with cues that do not alter the underlying semantic content but instead deemphasize contrast in areas least likely to promote social learning. Such a system could teach children that certain portions of the scene contain inherently less information than others by adaptively removing information from particular locations (e.g., through darkening and blurring) when children look at them.

Given this body of work, the present study moves GCET toward a more applied focus, exploring the feasibility of changing the attention strategies of very young children with ASD. Prior research has demonstrated that the gaze patterns of TD adults could be modified using gaze-contingent methods [Wang et al., 2015], and the present study extends this work to a population of young children with ASD. While it is still an open question as to whether increasing attention to faces will result in increased social engagement during live interactions, the current study takes the first step in this line of work by evaluating the feasibility of GCET to increase social attention in a noninteractive context. Given the increased plasticity of the brain in earlier developmental periods, GCET techniques could be even more effective at modifying gaze pattern strategies in young children as compared to older individuals.

This study examines the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a brief GCET social-attentional training program for young children with ASD. We began by creating dynamic attentional “normative maps” of attention toward naturalistic social scenes. Rather than presupposing specific regions of the scene, such as the face, that would represent prototypically visually salient locations, these maps were instead based on the unprompted, natural gaze behaviors of young TD children. Next, we designed GCET procedures that delivered redirection cues when a viewer deviated from the normative looking patterns. Finally, we implemented the GCET procedures with a group of children with ASD and compared their performance to that of TD controls and children with ASD randomized to a non-GCET control condition. Feasibility was assessed by examining participant data quality and successful completion of task batteries. Preliminary efficacy was measured by examining changes in looking patterns toward salient social features (i.e. faces) in children with ASD receiving GCET training versus controls. Looking to faces was chosen as the primary dependent variable in this preliminary efficacy study because it is a broad measure of social attention that has been found to capture the majority of attention in TD toddlers when viewing naturalistic social scenes [Frank et al., 2012]. Although attention to joint activities and language has been found to dominate attention during live caregiver–toddler interactions, research shows that faces tend to be most salient when viewing dynamic scenes and attention to faces is highly associated with clinical outcomes [Murias et al., 2018]. We hypothesized that children with ASD randomized to receive GCET training would direct a greater proportion of their looking time to faces during post-training test phases compared to children randomized to a no-training control condition. In an exploratory manner, because differences in social attention have been identified in toddlers with developmental delay [Adamson, Bakeman, Deckner, & Romski, 2008], we also examined the association between nonverbal ability and changes in attention to faces between baseline and post-treatment phases in children with ASD in the training group.

Method

The present study consisted of two stages of data collection: (a) normative data collection and (b) gaze modification. In the normative data collection stage, we collected gaze patterns from TD (TD-normative) children (n = 41 [19 males], age: M = 37.4 months, SD = 15.4 months) as they watched, under free-viewing conditions, social scenes involving an actress emulating interactions with the viewer. These normative data were used to generate a model of prototypical social scene viewing. Subsequently, in the Gaze Modification stage, we recruited young children with ASD (n = 35, [31 males], age: M = 34.0 months, SD = 9.1) to participate in a randomized control trial of experimental gaze manipulation (Clinical Trial Number Blinded for Review). Children with ASD were randomly assigned to either an adaptive Cue condition (Cue, n = 18) or a No-Cue condition (No-Cue, n = 19) using a pre-generated random ordering table. A subset of TD participants from the TD-normative group who saw the same videos in the same exact order as the ASD Cue and No-Cue groups were retained as a comparison group (TD, see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characterization

| TD | ASD Cue | ASD No-Cue | P value (cue vs. no-cue) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 39.2 (15.4) | 32.3 (8.7) | 35.4 (9.3) | 0.31 |

| N | 23 | 16 | 19 | - |

| Males | 10 | 13 | 18 | - |

| MSEL verbal DQ | 113.7 (27.8) | 71.5 (33.9) | 63.5 (28.9) | 0.50 |

| MSEL nonverbal DQ | 114.8 (15.9) | 92.1 (18.4) | 84.4 (21) | 0.30 |

| ADOS SA severity | NA | 5.6 (2.3) | 4.9 (2.1) | 0.37 |

| ADOS RRB severity | NA | 6.2 (2.6) | 7.1 (2.1) | 0.32 |

| ADOS total severity | NA | 5.7 (2.4) | 5.3 (2.1) | 0.60 |

Participants with a diagnosis of ASD were recruited from a university-based clinic specializing in the diagnosis of ASD; children with typical development were recruited through community advertisements. Exclusionary criteria included having a gestational age of less than 34 weeks, documented uncorrected hearing or visual impairments, nonfebrile seizure disorder, or known genetic syndrome. Diagnoses of ASD were based on clinical best estimate determined through a review of children’s medical and developmental histories as well as assessment of detailed social and cognitive functioning including: (a) Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Second Edition, Toddler Module (ADOS-2) [Lord et al., 2012] providing for direct evaluation of social deficits [in terms of social affect (SA) and restricted and repetitive behavior (RRB) calibrated severity scores (CSS)] [Hus, Gotham, & Lord, 2012] and a DSM-5 based algorithm for the diagnosis of ASD and non-ASD; and (2) Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) [Mullen, 1995] measuring verbal & nonverbal cognitive function. Ascertainment of typical development was determined through developmental screening questionnaires and behavioral observation during the MSEL. All procedures were approved through the university’s institutional review board and informed consent from parents was obtained before participation in any study procedures.

The ASD and TD groups were comparable in terms of age (t(32) = −1.47, P = 0.15). The ASD Cue and ASD No-Cue groups were comparable in terms of age, MSEL developmental quotient (DQ) (Verbal DQ, Nonverbal DQ), ADOS-2 SA severity scores, ADOS-2 RRB severity scores, and ADOS-2 calibrated severity scores (Table 1). See Figure 1 for enrollment details.

Figure 1.

Participant enrollment details.

Apparatus.

An SR Eyelink 1000 Plus 500 Hz eye-tracking system was used to record the participants’ eye movements. Participants sat in a car seat at a distance of around 600 mm away from a 19-in. display screen. The participants’ heads were free to move in all directions throughout the experiment. To avoid distraction, the experiment room was soundproofed with dimmed lights. Stimuli were displayed through the MATLAB Psychtoolbox platform [Kleiner et al., 2007].

Stimuli.

Videos were 1,280 × 720 pixels, displayed on a screen with a resolution of 1,680 × 1,050 pixels and a physical screen size of 475 × 298 mm3. Social videos depicted an actress engaged in a variety of actions and environments so as to provide for a general index of “social looking.” Actions included dyadic engagement activities (e.g., looking directly toward the camera and speaking in motherese, singing songs, or making nonverbal utterances), nonverbal auditory-motion attentional orienting (e.g., snapping fingers, clapping, or tapping the table), and simple object-based activities (e.g., folding paper) (see Fig. 1B). Scenes were post-processed and combined with either social or nonsocial backgrounds with fast or slow-moving components. Other experiments were presented interleaved with these social videos, but will be analyzed in future work.

Normative Data Collection Stage

In the normative data collection stage, we collected eye-tracking data from a group of TD children viewing unaltered Stimuli. From their gaze patterns, we developed a model of prototypical looking (Model Generation). We then created an adapted version of the stimuli, which was designed to direct attention toward locations of prototypical looking. These adapted stimuli (Gaze Modification Stimuli) were designed to be shown as cues to children with ASD to modify their looking patterns in the Gaze Modification Stage.

Model Generation

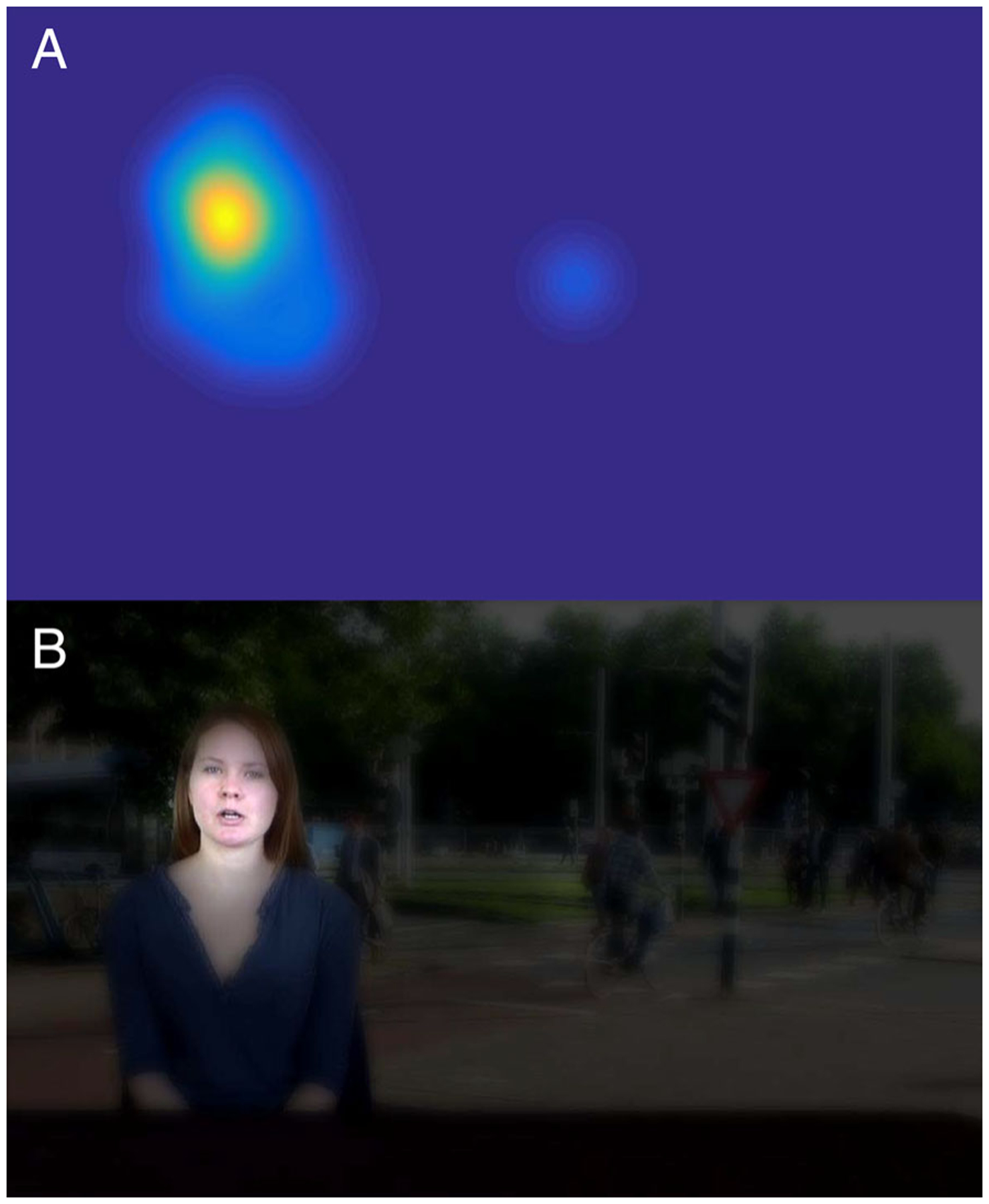

Data collected from the TD-normative children were used to create a “prototypical map” of social scene looking. Gaze data from each TD-normative participant was median-aggregated in 200 msec bins, using a 100 msec sliding window. Looking positions were combined across participants to generate “normative heatmaps” (i.e., 2-D Gaussian filtered with sigma = 1 visual degree within an 8-degree window) representing the group distribution of looking by TD-normative children within each time bin, with spurious gaze points (i.e., gaze locations with fewer than three neighbors within 2° of visual angle) eliminated (see Figure 2A). A sensitivity analysis of the stability of normative maps was calculated using 100× repeated folded subsampling for different fold sizes (e.g., 10-fold subsampling would randomly divide the TD population into 10 approximately equivalent sized samples, and use all permutations of nine choose 10 samples to compare against the original normative map containing 100% of participants; this process was repeated 100 times for different random divisions of the population). Average differences in maps for 10, 5, 4, and 2-fold subsampling were 1.9%, 3.2%, 3.5%, and 5.1%, respectively, suggesting a high stability of the normative map generation.

Figure 2.

(A) Example of heatmap constructed from normative data of TD participants. (B) Corresponding filter applied to video frame, with the regions that have high values in the TD’s heatmap left as bright and sharp as they were in the original scene, whereas the regions with low or no values in the heatmap have been darkened and blurred.

Gaze Modification Stimuli (Cue Condition)

From the normative heatmaps, adaptive cueing videos were created. These videos were designed to redirect attention toward locations in the scene consistent with TD looking patterns. Videos were manipulated so that the places where the TD-normative group looked were clear and bright, whereas locations where they did not look were blurred and dark. This was done in a two-stage process where blurred versions of scenes (Gaussian sigma = 0.25°, window size = 1°) were mixed with the unmodified non-blurred scenes using the normative heatmap as a window (i.e., alpha channel, with the top 20% of values clamped to 100% clarity) and then this composite video subsequently mixed with a uniformly black background (again using the normative heatmap as an alpha channel) (see Figure 2B). All cueing videos were precomputed before the Gaze Modification Stage so as to enable real-time responsiveness. These stimuli were only shown to the ASD-Cue group.

Gaze Modification Stage

In the Gaze Modification stage, children with ASD were exposed to Cue and No-Cue condition experimental sessions (as appropriate to their random assignment). Looking patterns were compared between children with ASD in the Cue and No-Cue conditions as well as between a subset of TD children from the Normative Collection Stage who saw stimuli in an identical presentation order.

Cue Condition

During the Cue condition, the scene was altered by algorithmic redirection when the attention of participants drifted from the TD-normative map. Cueing movies maintained the original scene when normative gaze patterns were followed, but darkened areas outside the normative heat map when attention deviated (Fig. 2B).

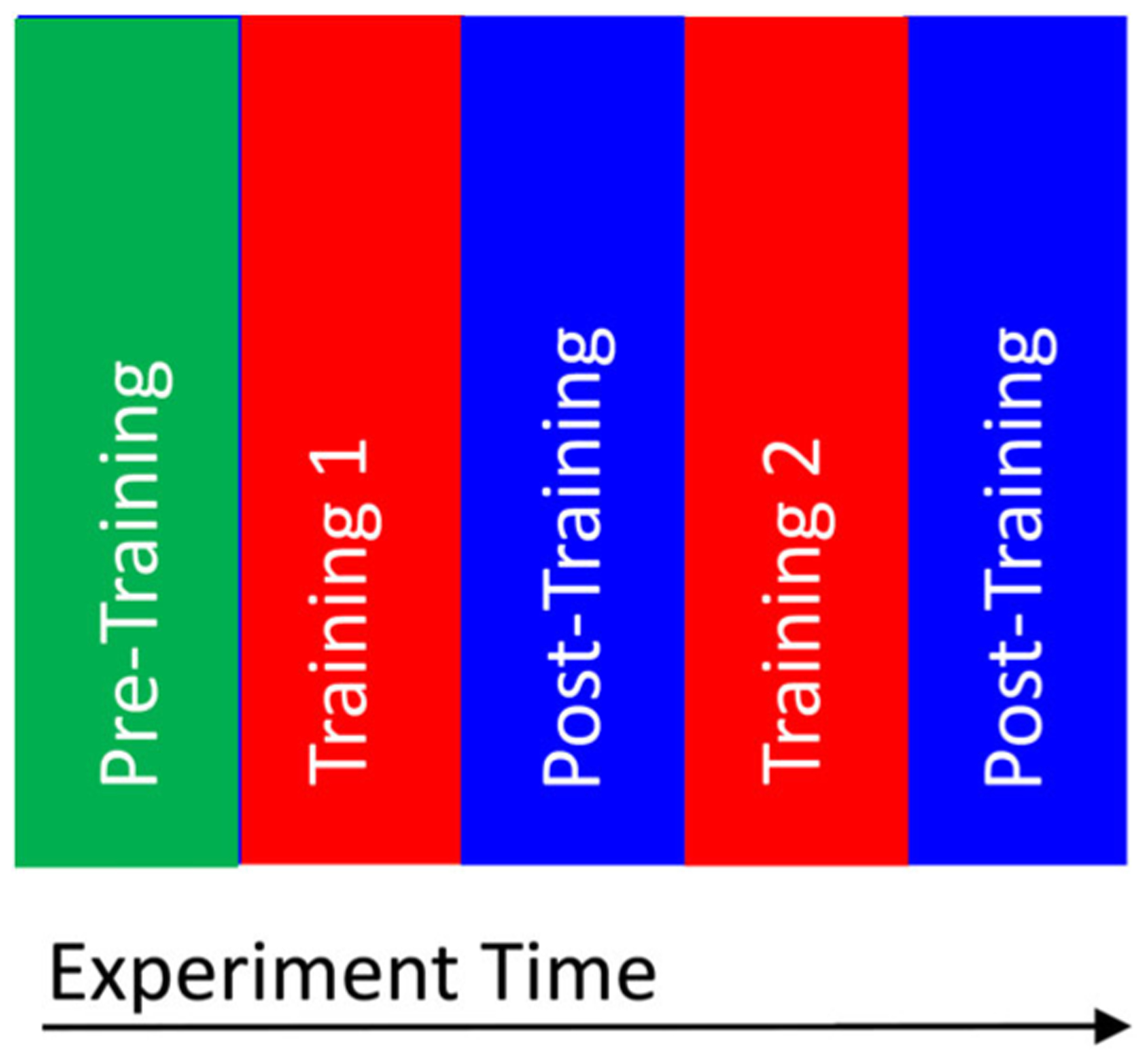

All eye-tracking sessions were delivered in the following order: Pre-Training, Training 1, Post-Training 1, Training 2, and Post-Training 2, as shown in Figure 3. Every phase was succeeded by a five-point calibration lasting approximately 10 sec. Each trial started with a 500 msec central fixation to provide a stable starting point for gaze and was followed by a 7-sec social video clip. Training phases employed gaze modification strategies where trials were gaze-contingent for the ASD-Cue group only, with adaptive cueing videos with darkening and blurring effects. Each training phase included 16 trials with different social videos. Test phases (i.e., Post-Training 1 and Post-Training 2) with unadulterated videos of no modification were designed to assess change in gaze patterns. Similarly, the Pre-Training phase showed unmodified videos to serve as a baseline for subsequent phases. Each test phase included four trials with different social videos. A complete session comprised 44 social videos in total and lasted about 15 min.

Figure 3.

Structure of the training phases.

No-Cue Condition

For the ASD No-Cue group and the TD group the structure of video stimuli was identical to the Cue condition, except that no gaze-modification (i.e., gaze cueing) was administered to participants. The only differences between the experimental Cue condition and the control No-Cue condition occurred in the Training phases (in both Training 1 and Training 2). In the No-Cue condition, children (ASD No-Cue and TD) viewed unadulterated videos (as in the Normative Data Collection Stage).

Data Reduction

Eye-tracking data were post-processed with a custom data pipeline programmed in MATLAB. Processing steps included calibration, recalibration, and blink detection [Duchowski, 2003; Shic, 2008]. Our data reduction included removal of invalid trials, in which either less than 50% onscreen looking or more than 2.5° of calibration error occurred. %Valid Trials was calculated as the number of valid trials within each phase for each group divided by the total number of administered trials. Dependent variables for eye tracking included %Scene, the percentage of time looking at the screen divided by the trial duration and %Face, the percentage of time spent looking at the face of the actress divided by the total looking time on the screen. %Face was the primary dependent variable of this study.

Prior to the primary analyses, we examined if Training 1, Post-Training 1 (block 1) differed from Training 2, Post-Training 2 (block 2) in %Scene and %Valid Trial. The results suggested that no difference between block 1 and block 2 was found, nor were any two-way or three-way interactions between block, phase, and group. Thus, for the subsequent analysis we combined the block 1 and block 2 Training and Post-Training.

Data Analysis

A linear mixed model was used to evaluate %Valid trials, %Scene, and %Face during social video clips. Factors included group (3) and experimental phase (3). To control for the spatial and visual skill of the participants and to facilitate comparison between children with ASD and TD controls, the MSEL Nonverbal DQ was included as a covariate. A compound symmetry covariance matrix was used to model repeated trials.

Pearson correlations were calculated between the ADOS-2 scores and MSEL Nonverbal DQ and the difference between Pre- and Post-Training of %Face (Δ%Face = post − pre), as well as the difference between Pre- and Post-Training of %Scene (Δ%Scene = post − pre). We constructed an ANCOVA model for Δ%Face with group as a factor and MSEL Nonverbal DQ as the covariate.

Results

Feasibility Results

Participant loss.

The number of participants lost in each condition was similar (2 out of 18 in the ASD-Cue group, 0 out of 19 in the ASD-No-Cue group, and 0 out of 23 in the TD group). (χ2 = 0.062, P = 0.80; Fisher exact test, P = 0.488). The loss in the ASD-Cue group was due to inattention to the paradigm necessitating experiment abort.

%Valid trials.

A group (3: ASD Cue, ASD No-Cue, TD) × phase (3: Pre-Training, Training, Post-Training) linear mixed model on %Valid Trials with MSEL Nonverbal DQ as a covariate showed no significant main effect of group (F(2,43) = 1.15, p = 0.33), no interaction between phase and group (F(4,160) = 0.83, p = 0.51), and a marginally significant effect of phase (F(2,160) = 2.97, p = 0.054) suggesting a trend toward fewer valid trials during Training as compared to Pre-Training. The effect of MSEL Nonverbal DQ (F(1,38) = 2.26, P = 0.14) was not significant.

%Scene.

A group (3) × phase (3) linear mixed model on %Scene with MSEL Nonverbal DQ as a covariate indicated no effect of group (F(2,46) = 0.32, p = 0.73), a significant main effect of phase (F(2,162) = 5.09, p = 0.007), and a significant group × phase interaction (F(4,162) = 2.45, P = 0.048) (see Table 2). During the Post-Training phase, the ASD Cue group looked marginally more at the scene than ASD No-Cue (P = 0.09, d = 0.58); no differences between TD and either ASD Cue (P = 0.68, d = 0.14) or No-Cue groups were observed (P = 0.23, d = 0.44). Between-group comparisons indicated that during the Pre-Training and training phases, the groups did not differ in their %Scene (Ps > 0.1).

Table 2.

Summary of Results (mean [SD])

| Phase | %Face | %Scene | %Valid trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| TD | |||

| Pre-training | 42 (14) | 93 (8) | 88 (25) |

| Training | 43 (14) | 94 (4) | 84 (24) |

| Post-training | 46 (17) | 90 (9) | 86 (23) |

| ASD Cue | |||

| Pre-training | 36 (13) | 91 (12) | 83 (26) |

| Training | 35 (13) | 91 (8) | 76 (25) |

| Post-training | 34 (16) | 91 (8) | 84 (25) |

| ASD No-Cue | |||

| Pre-training | 36 (8) | 95 (6) | 84 (24) |

| Training | 29 (10) | 94 (7) | 67 (28) |

| Post-training | 23 (15) | 90 (11) | 73 (26) |

Within-group comparisons indicated that the TD group had a significant decrease in %Scene from Training to Post-Training (P = 0.012, d = 0.46), but there was no difference between %Scene from Pre-Training to Training, or Pre-Training to Post-Training (Ps > 0.1). The ASD No-Cue group showed a significant decrease in %Scene from the Pre-Training phase comparing to both Training (P = 0.012, d = 0.65) and Post-Training test phases (P < 0.001, d = 1.00). The ASD Cue group showed no differences in %Scene between Pre-Training, Training, and Post-Training phases (Ps > 0.1). The effect of MSEL Nonverbal DQ was not significant (F(1,44) = 2.37, P = 0.13).

Preliminary Efficacy Results

%Face.

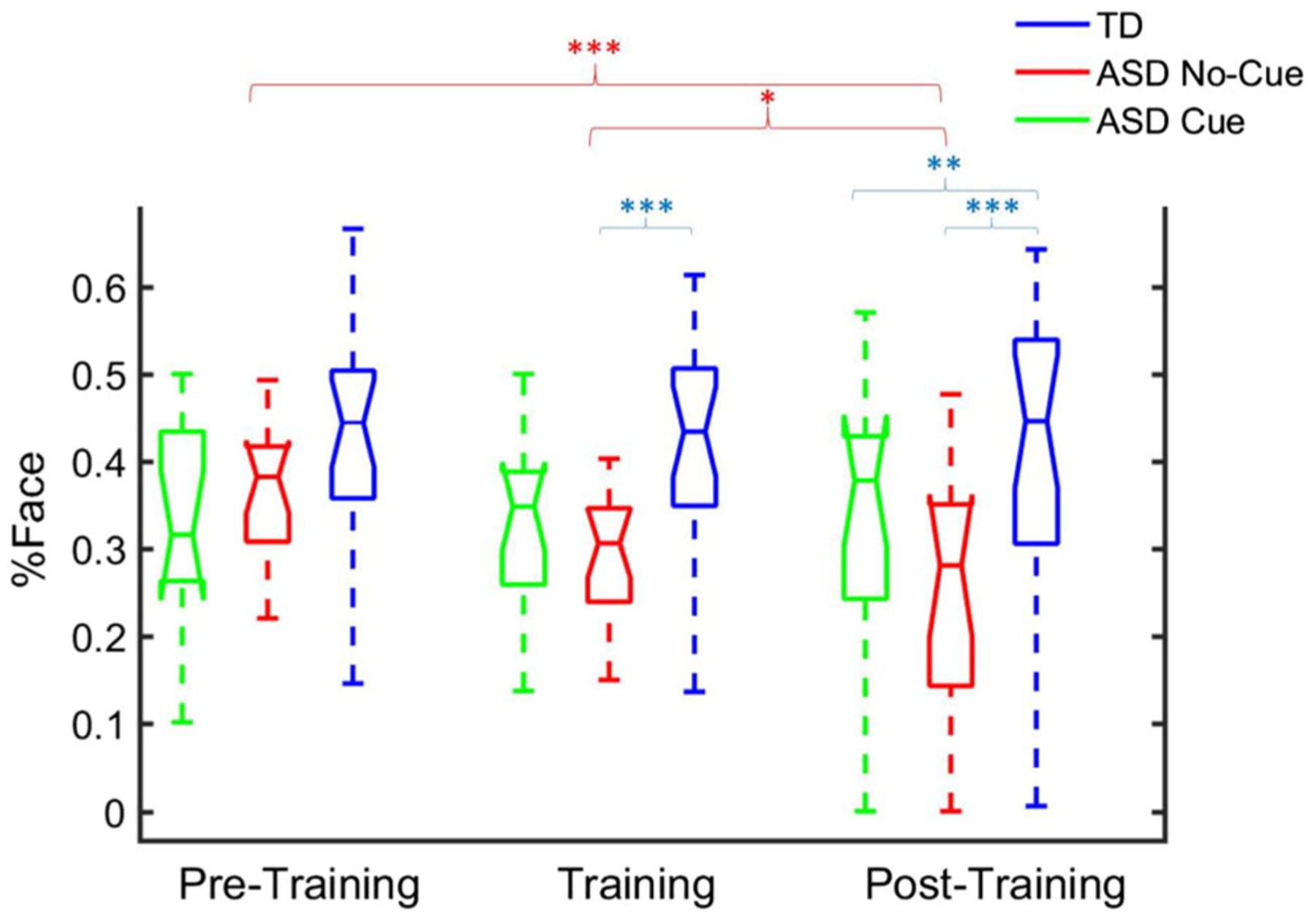

A group (3) × phase (3) linear mixed model with MSEL Nonverbal DQ as a covariate indicated a main effect of group for %Face (F(2,47) = 6.42, P = 0.003), no effect of phase (F(2,163) = 1.71, P = 0.18), and a significant group × phase interaction (F(4, 163) = 3.06, P = 0.018). Post-Training, the TD group had higher %Face than both the ASD No-Cue (P < 0.001, d = 1.73) and ASD Cue (P = 0.009, d = 0.90) groups; the ASD Cue group had higher %Face than the ASD No-Cue group (P = 0.015, d = 0.83). Only the ASD No-Cue group had a significant decrease of %Face from Pre-Training to Training (P = 0.028, d = 0.59) and Post-Training (P = 0.001, d = 1.00), with no trend in the TD and ASD Cue groups (Ps > 0.1). During training, the TD group had higher %Face than the ASD No-Cue group (P = 0.001, d = 1.12), but the ASD Cue group was different neither from the TD group (P = 0.062, d = 0.61) nor the ASD No-Cue group (P = 0.11, d = 0.51). At Pre-Training there was no difference between groups (Ps > 0.10) (see Fig. 4). The effect of MSEL Nonverbal DQ was not significant (F(1,44) = 0.32, P = 0.57).

Figure 4.

Boxplot of percentage looking at actress face. y-axis: Percentage looking at actress face (%Face). x-axis: Pre-training (baseline), training, and post-training.

Correlations.

Pearson’s r correlation coefficient analysis indicated a significant negative relationship between the Nonverbal Developmental Quotient (NVDQ) and Δ%Face (r(14) = −0.64, P = 0.013) in the ASD Cue group, suggesting that children with lower NVDQ showed less decline in % Face from Pre-Training to Post-Training. There were no significant correlations between the Nonverbal DQ and Δ% Face in the TD group (r(18) = 0.113, P = 0.65) or in the ASD No-Cue group (r(14) = −0.38, P = 0.18). The results were similar using nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation. A follow-up ANCOVA (with groups and phases as factors and Nonverbal DQ as the covariate) confirmed the between-group differences in this relationship (F(2, 37) = 3.58, P = 0.04): only in the ASD Cue group was there a significant effect of MSEL Nonverbal DQ (t(16) = 2.13, P = 0.041, partial eta squared = 0.12), not in the ASD No-Cue or TD groups (Ps > 0.3).

Discussion

The study provides support for the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of automated GCET attentional training systems. We observed low dropout rates (11%) and a high proportion of valid trials (76%–84%). Despite the attention training period being relatively short, GCET training appeared to impact looking patterns in children with ASD: at Pre-Training, there were no differences in looking patterns between the ASD Cue and No-Cue group, but during Post-training, the ASD Cue group exhibited more looking at the social stimuli than the ASD No-Cue group. Because the Training phase used a different set of videos than the Post-Training phase, these observed differences are likely to be due to more generalized changes in attentional processes than training toward specific stimuli content. The sustained looking time at the face of the actress with new videos is an indication of maintained engagement with the emulated dyadic exchange as well as the transfer of attentional strategies associated with that maintenance.

In pairwise comparisons across time, the ASD No-Cue group was the only group to show a significant decrease in attention toward faces from Pre-Training to Training and Post-Training. Similar to their TD peers, the ASD Cue group maintained their attention toward the face over phases. It is possible that the interactive nature of the cue condition was sufficient to engage children with ASD to a greater extent, leading to improved ability to focus on scene-relevant details such as the face. It is important to note, however, that regardless of the mechanism by which GCET attentional training bolsters face looking, mitigating the natural decrease in face looking over time exhibited by children with ASD (as in the No-Cue group) provides those children additional opportunities for understanding cues related to facial expressions and for social learning. From this perspective, the utility of GCET strategies for teaching social attention may be to help children with ASD discover the natural informativeness and utility of social phenomena. This approach of leveraging natural reinforcers for bootstrapping learning reflects a long tradition of intervention research in ASD [Schreibman et al., 2015].

The negative correlation observed in the ASD Cue group between the Pre–Post difference in face looking and MSEL Nonverbal DQ scores suggests that GCET training systems may be of special value for more impaired children. These children may have the greatest difficulty in recognizing key components in a social scene. Once the children were directed to the face, it is possible that the intrinsic saliency of the face continued to maintain their engagement. Refinement of GCET training systems may consider the nature of specific attentional deficits to achieve optimal efficacy, much like traditional interventions where minimum symptom thresholds are often criteria for inclusion [Hardan et al., 2014; McCracken et al., 2002; Owen et al., 2009].

The training described here was designed to be of limited intensity, as this feasibility and preliminary efficacy study aimed to advance and refine novel methodology and explore developmental phenomena. These results highlight the promise and potential of GCET as a general methodology for boosting social attention. The results of our study suggest a natural decrease in prolonged engagement toward social information in children with ASD. This decrease seems to be attenuated by the presence of GCET cues for redirecting attention toward social information. It is possible that GCET cues administered over longer periods of time could help bolster the value of faces and social information to children with ASD. For children with ASD who have a primary difficulty automatically isolating and engaging with social phenomena, this increased value may manifest in the ability to more quickly orient to and engage with faces. For children who have difficulty maintaining interest in faces, GCET cues could help them recognize the complexity, richness, and value of faces. In either case, although maintained social looking may not be sufficient to lead to real-world improvements in social ability in children with ASD, it likely provides more opportunities for social learning [Bandura, 1986]. Hopefully, such techniques over extended periods of time would augment and improve the effectiveness of traditional interventions as well as target specific difficulties in social attention. Caution is warranted, however, as it is also possible that specific guidance regarding “where to look,” given more fundamental social motivation deficits [Chevallier, Kohls, Troiani, Brodkin, & Schultz, 2012], may have little impact on deeper social information processing and, consequently, minimal effects on social interactions.

We note that there was no evidence of decreased looking at the screen in the ASD Cue group during either Training or Post-Training, suggesting that the adaptive cueing did not elicit an aversive reaction in children with ASD. In our study, children’s heads were free to move in all directions. If children in our Cue condition found redirection toward social information aversive, we would expect overall attention to the scene to decrease, especially during training, due to looking away from the screen. This was not observed. In addition, children with ASD in the Cue condition continued to look at faces after training, suggesting that they continued to orient to and engage with social information even after all artificial external supports for redirection of attention were removed. By contrast, we observed a steady decrease in attention to faces in the no-cue condition, an effect more consistent with general disinterest in social information compounding over time rather than aversion to faces. Nonetheless, the potential aversive nature of faces to some children with ASD should be a consideration in the development and deployment of automatic systems for behavioral intervention in children with ASD.

It is important to note that although the primary dependent variable used in our preliminary efficacy analyses was looking to the face, this is not the only important feature of the social environment. Research on live dyadic interactions highlight the importance of not only looking to the face, but also of looking to symbols and objects of joint engagement [Adamson, Bakeman, & Deckner, 2004]. While the stimuli used for this study were designed to elicit extensive scanning of the face in typical developing children through the use of cues such as speech, facial expressions, and direct gaze, the unfolding of both nonsocial and social salient cues throughout the course of the dynamic naturalistic scenes allowed for significant contextual modulation of attention. Our approach, which uses the time course of attention from TD children as a template for teaching, may thereby provide access to more natural visual exploratory behaviors. From this perspective, retained attention toward faces in the ASD Cue-group may reflect a down-stream impact of this broader goal.

Future Work and Limitations

Future work plans to extend the adaptive training time to longer and more sessions across days, and to follow the progress of participants to evaluate longer-range training effects. Such extensions would also help to disentangle possible confounds of novelty on attentional processes. To study the generalizability of GCET interventions, additional research will measure not only looking patterns toward social videos on a screen, but also real-world looking behaviors toward communicative partners. This, and further examination of impacts on real-world adaptive, social skills, is especially important considering generalization gaps between conceptual learning and adaptive application in areas such as Theory of Mind [Begeer et al., 2011]. Larger sample sizes are also needed, as the current samples in this study are small and sample variability, in terms of clinical characteristics, is high. Reproducibility and replicability of this work remain to be established in larger, more intensive follow-up studies beyond this current feasibility and preliminary efficacy study. The present study matched participants from the ASD and TD groups on chronological age; however, teaching cognitively delayed-participants to view as their developmentally matched TD peers would (e.g., using scanning patterns of 14-month old TD toddlers instead of chronological age-matched controls) may be an important future direction. Similarly, the actresses in the presented scenes emulated a simple, unidirectional component of dyadic exchanges but were not interactive, and thus did not represent an ecologically valid, dyadic interaction. The development, extension, and examination of more naturally and directly gaze-interactive systems, and fuller consideration of the complexity of gaze in social interactions and conversation [see Rossano, 2012] are important areas of further exploration. In our implementation, we tied adaptive darkening to deviation from prototypical looking patterns. It is possible that providing this “spotlight” alone, without gaze contingency, would have been sufficient to alter and maintain interest by children with ASD to the presented social scenes. Future examination of stronger control conditions will be necessary to clarify mechanistic relationships. Finally, the goal of the GCET strategy presented in this work is to use behavioral principles to provide access to and appreciation of normative visual attentional strategies, as opposed to their rote memorization. Yet, behavioral modification technologies that operate at the precision, speed, and tenacity of the algorithms presented in this work are relatively new, and even newer are systems operating at the level of low-level social attention. Little is yet known about their fundamental nature and short-term effects. Even less is known about their longer-term impacts. As these technologies develop, continued, cautious research into their impacts on child development is critical so as to more fully understand and appreciate the ethics of such tools in the balance of potential benefits against risks.

Conclusions

Compared with the ASD No-Cue group, GCET was effective at mitigating decreases of attention toward the face of the onscreen social characters in the ASD Cue group. After adaptive training, the attention toward the video actress was significantly higher in the ASD Cue group than the No-Cue group. Negative associations between nonverbal ability and changes in face looking imply that this approach may have particular relevance as a social-attentional training tool for children with ASD with greater developmental impairment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelly K. Powell, So Hyun Kim, Megan Lyons, Elizabeth Schoen Simmons, Karyn Bailey, and Amy Giguere Carney for their contribution to sample characterization; Benjamin D. Oakes, Marek Michalowski, Brian Scassellati, Ami Klin, and Warren Jones for their early contributions to this work; Emily B. Prince, Yeojin Amy Ahn, Grace Chen, Lauren DiNicola, Alexandra C. Dowd, Lilli Flink, Claire E. Foster, Eugenia Gisin, Gabriella Greco, Minah Kim, Marilena Mademtzi, and Michael Perlmutter for their help in data collection and experimental development. We would like to thank Kelsey Dommer for her editorial assistance and scientific commentary. This article was made possible through funding, resources, and experiences provided by: NIH Awards R21 MH102572, K01 MH104739, CTSA UL1 RR024139, R03 MH092618, NIH R01 MH100182, R01 MH087554; NSF CDI #0835767, Autism Speaks Meixner Postdoctoral Fellowship (to Q. Wang), the Hilibrand Foundation, and the FAR Fund. Views in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions of any funding agency.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Quan Wang, Carla A. Wall, Jessica L. Bradshaw, Suzanne L. Macari, and Katarzyna Chawarska report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interests. Erin A. Barney is an employee of Cogstate. Frederick Shic is a consultant for Janssen and Roche.

References

- Abravanel E, Levan-Goldschmidt E, & Stevenson MB (1976). Action imitation: The early phase of infancy. Child Development, 47(4), 1032–1044. 10.2307/1128440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, & Deckner DF (2004). The development of symbol-infused joint engagement. Child Development, 75(4), 1171–1187. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Deckner DF, & Romski M (2008). Joint engagement and the emergence of language in children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(1), 84–96. 10.1007/s10803-008-0601-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, & Adamson LB (1984). Coordinating attention to people and objects in mother-infant and peer-infant interaction. Child Development, 55(4), 1278–1289. 10.2307/1129997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Begeer S, Gevers C, Clifford P, Verhoeve M, Kat K, Hoddenbach E, & Boer F (2011). Theory of mind training in children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(8), 997–1006. 10.1007/s10803-010-1121-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekele E, Crittendon J, Zheng Z, Swanson A, Weitlauf A, Warren Z, & Sarkar N (2014). Assessing the utility of a virtual environment for enhancing facial affect recognition in adolescents with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1641–1650. 10.1007/s10803-014-2035-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertenthal B (1996). Origins and early development of perception, action, and representation. Annual Review of Psychology, 47, 431–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertone A, Mottron L, Jelenic P, & Faubert J (2003). Motion perception in autism: A “complex” issue. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 15(2), 218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertone A, Mottron L, Jelenic P, & Faubert J (2005). Enhanced and diminished visuo-spatial information processing in autism depends on stimulus complexity. Brain, 128(10), 2430–2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR, Frith U, Smith N, Abell F, & Cipolotti L (2002). Fractionation of visual memory: Agency detection and its impairment in autism. Neuropsychologia, 40(1), 108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake R, Turner LM, Smoski MJ, Pozdol SL, & Stone WL (2003). Visual recognition of biological motion is impaired in children with autism. Psychological Science, 14 (2), 151–157. 10.1111/1467-9280.01434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono MA, Daley T, & Sigman M (2004). Relations among joint attention, amount of intervention and language gain in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34 (5), 495–505. 10.1007/s10803-004-2545-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J, Koegel LK, & Koegel RL (2017). Improving functional language and social motivation with a parent-mediated intervention for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2443–2458. 10.1007/s10803-017-3155-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J, Shic F, Holden A, Horowitz E, Barrett A, German T, & Vernon T (2019). The use of eye tracking as a biomarker of treatment outcome in a pilot randomized clinical trial for young children with autism. Autism Research, 12(5), 779–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J, Steiner AM, Gengoux G, & Koegel LK (2015). Feasibility and effectiveness of very early intervention for infants at-risk for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45 (3), 778–794. 10.1007/s10803-014-2235-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma Y, Koegel RL, & Koegel LK (2004). Joint attention and children with autism: A review of the literature. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 10(3), 169–175. 10.1002/mrdd.20036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DJ, Shic F, Macari S, & Chawarska K (2014). Gaze response to dyadic bids at 2 years related to outcomes at 3 years in autism spectrum disorders: A subtyping analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(2), 431–442. 10.1007/s10803-013-1885-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M (2006). Instrumental, social, and shared goals and intentions in imitation In Rogers SJ & Williams JHG (Eds.), Imitation and the social mind: Autism and typical development (pp. 48–70). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M, Nagell K, & Tomasello M (1998). Social cognition, joint attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 63(4), i–vi), 1–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Baron-Cohen S, Swettenham J, Baird G, Cox A, & Drew A (2000). Testing joint attention, imitation, and play as infancy precursors to language and theory of mind. Cognitive Development, 15(4), 481–498. [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Swettenham J, Baron-Cohen S, Cox A, Baird G, & Drew A (1997). Infants with autism: An investigation of empathy, pretend play, joint attention, and imitation. Developmental Psychology, 33, 781–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawarska K, Macari S, & Shic F (2012). Context modulates attention to social scenes in toddlers with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(8), 903–913. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02538.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, & Schultz RT (2012). The social motivation theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(4), 231–239. 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombi C, Liebal K, Tomasello M, Young G, Warneken F, & Rogers SJ (2009). Examining correlates of cooperation in autism: Imitation, joint attention, and understanding intentions. Autism, 13(2), 143–163. 10.1177/1362361308098514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courgeon M, Rautureau G, Martin J-C, & Grynszpan O (2014). Joint attention simulation using eye-tracking and virtual humans. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 5 (3), 238–250. 10.1109/TAFFC.2014.2335740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G (2008). Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 20(03), 775–803. 10.1017/S0954579408000370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, … Varley J (2010). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The early start Denver model. Pediatrics, 125(1), e17–e23. 10.1542/peds.2009-0958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Toth K, Abbott R, Osterling J, Munson J, Estes A, & Liaw J (2004). Early social attention impairments in autism: Social orienting, joint attention, and attention to distress. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchowski AT (2003). Eye tracking methodology: Theory and practice (1st ed.). London, UK; Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Evers K, Van Belle G, Steyaert J, Noens I, & Wagemans J (2017). Gaze-contingent display changes as new window on analytical and holistic face perception in children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Development, 89, 430–445. 10.1111/cdev.12776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MC, Vul E, & Johnson SP (2009). Development of infants’ attention to faces during the first year. Cognition, 110(2), 160–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MC, Vul E, & Saxe R (2012). Measuring the development of social attention using free-viewing. Infancy, 17(4), 355–375. 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2011.00086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren CC, Sarty M, & Wu PYK (1975). Visual following and pattern discrimination of face-like stimuli by newborn infants. Pediatrics, 56(4), 544–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynszpan O, Nadel J, Constant J, Le Barillier F, Carbonell N, Simonin J, … Courgeon M (2009). A new virtual environment paradigm for high functioning autism intended to help attentional disengagement in a social context Bridging the gap between relevance theory and executive dysfunction Virtual Rehabilitation International Conference, 2009, 51–58. IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- Grynszpan O, Simonin J, Martin J-C, & Nadel J (2012). Investigating social gaze as an action-perception online performance. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 94 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardan AY, Gengoux GW, Berquist KL, Libove RA, Ardel CM, Phillips J, … Minjarez MB (2014). A randomized controlled trial of Pivotal Response Treatment Group for parents of children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 884–892. 10.1111/jcpp.12354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecke AVV, Mundy PC, Acra CF, Block JJ, Delgado CE, Parlade MV, … Pomares YB (2007). Infant joint attention, temperament, and social competence in preschool children. Child Development, 78(1), 53–69. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00985.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes C (2001). Causes and consequences of imitation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5(6), 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins IM, Gower MW, Perez TA, Smith DS, Amthor FR, Casey Wimsatt F, & Biasini FJ (2011). Avatar assistant: Improving social skills in students with an ASD through a computer-based intervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(11), 1543–1555. 10.1007/s10803-011-1179-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hus V, Gotham K, & Lord C (2012). Standardizing ADOS domain scores: Separating severity of social affect and restricted and repetitive behaviors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2400–2412. 10.1007/s10803-012-1719-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH, Dziurawiec S, Ellis H, & Morton J (1991). Newborns’ preferential tracking of face-like stimuli and its subsequent decline. Cognition, 40(1), 1–19. 10.1016/0010-0277(91)90045-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W, Carr K, & Klin A (2008). Absence of preferential looking to the eyes of approaching adults predicts level of social disability in 2-year-old toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(8), 946–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith A (2007). Atypical epigenesis. Developmental Science, 10(1), 84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner M, Brainard D, Pelli D, Ingling A, Murray R, & Broussard C (2007). What’s new in Psychtoolbox-3 In: Perception, 36, 14 Arezzo, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Klin A, Jones W, Schultz R, & Volkmar F (2003). The enactive mind, or from actions to cognition: Lessons from autism. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 358(1430), 345–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri U, Bekele E, Dohrmann E, Warren Z, & Sarkar N (2013). Design of a virtual reality based adaptive response technology for children with autism. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 21(1), 55–64. 10.1109/TNSRE.2012.2218618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri U, Warren Z, & Sarkar N (2011). Design of a gaze-sensitive virtual social interactive system for children with autism. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 19(4), 443–452. 10.1109/TNSRE.2011.2153874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leekam S, & Ramsden C (2006). Dyadic orienting and joint attention in preschool children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(2), 185–197. 10.1007/s10803-005-0054-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, & Bishop S (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule: ADOS-2. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken JT, McGough J, Shah B, Cronin P, Hong D, Aman MG, … McMahon D (2002). Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. New England Journal of Medicine, 347(5), 314–321. 10.1056/NEJMoa013171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzoff A, & Moore M (1977). Imitation of facial and manual gestures by human neonates. Science, 198(4312), 75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne E, Swettenham J, Hansen P, Campbell R, Jeffries H, & Plaisted K (2002). High motion coherence thresholds in children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(2), 255–263. 10.1111/1469-7610.00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C, & Dunham PJ (Eds.). (1995). Joint attention: Its origins and role in development (1st ed.). Hillsdale, NJ; Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Mottron L, Dawson M, Soulieres I, Hubert B, & Burack J (2006). Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: An update, and eight principles of autistic perception. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(1), 27–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen EM (1995). Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P, & Vaughan A (2002). Joint attention and its role in the diagnostic assessment of children with autism. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 27(1/2), 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Murias M, Major S, Davlantis K, Franz L, Harris A, Rardin B, … Dawson G (2018). Validation of eye-tracking measures of social attention as a potential biomarker for autism clinical trials. Autism Research, 11(1), 166–174. 10.1002/aur.1894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberwelland E, Schilbach L, Barisic I, Krall SC, Vogeley K, Fink GR, … Schulte-Rüther M (2016). Look into my eyes: Investigating joint attention using interactive eye-tracking and fMRI in a developmental sample. NeuroImage, 130, 248–260. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen R, Sikich L, Marcus RN, Corey-Lisle P, Manos G, McQuade RD, … Findling RL (2009). Aripiprazole in the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. Pediatrics, 124(6), 1533–1540. 10.1542/peds.2008-3782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R (2008). Interventions to improve communication in autism. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 17(4), 835–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichow B, & Fr V (2010). Social skills interventions for individuals with autism: Evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice LM, Wall CA, Fogel A, & Shic F (2015). Computer-assisted face processing instruction improves emotion recognition, mentalizing, and social skills in students with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 2176–2186. 10.1007/s10803-015-2380-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ (2000). Interventions that facilitate socialization in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(5), 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, Hepburn SL, Stackhouse T, & Wehner E (2003). Imitation performance in toddlers with autism and those with other developmental disorders. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 44(5), 763–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, & Williams JHG (2006). Imitation and the social mind: Autism and typical development (pp. 277–309). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rossano F (2012). Gaze in conversation. In The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 308–329). West Sussex, UK: 10.1002/9781118325001.ch15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schertz HH, & Odom SL (2007). Promoting joint attention in toddlers with autism: A parent-mediated developmental model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37 (8), 1562–1575. 10.1007/s10803-006-0290-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilbach L (2014). On the relationship of online and offline social cognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 278 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibman L, Dawson G, Stahmer AC, Landa R, Rogers SJ, McGee GG, … Halladay A (2015). Naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Empirically validated treatments for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(8), 2411–2428. 10.1007/s10803-015-2407-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheis MT, & Aa R (2001). The application of virtual reality technology in rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology, 46, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shic F (2008). Computational Methods for Eye-Tracking Analysis: Applications to Autism (Ph.D. thesis). Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Shic F, Bradshaw J, Klin A, Scassellati B, & Chawarska K (2011). Limited activity monitoring in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Brain Research, 1380, 246–254. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.11.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J, O’Brien J, Riggs K, Braddick O, Atkinson J, & Wattam-Bell J (2000). Motion processing in autism: evidence for a dorsal stream deficiency. Neuroreport, 11(12), 2765–2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M, Finelli J, Marvin A, Garrett-Mayer E, Bauman M, & Landa R (2007). Response to joint attention in toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorder: A prospective study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(1), 37–48. 10.1007/s10803-006-0335-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans B, & Schilbach L (2014). Investigating alterations of social interaction in psychiatric disorders with dual interactive eye tracking and virtual faces. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 758 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M (1996). Do apes ape? In Heyes CM & Galef BG (Eds.), Social learning in animals: The roots of culture. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trepagnier C (2006). Acceptance of a virtual social environment by pre-schoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Presented at the Catholic University of America. Catholic University of America. [Google Scholar]

- Trepagnier CY, Sebrechts MM, Finkelmeyer A, Stewart W, Woodford J, & Coleman M (2006). Simulating social interaction to address deficits of autistic spectrum disorder in children. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(2), 213–217. 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang T, Shic F, Nguyen B, Zolfaghari R, & Johnson S (2015). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors Guiding Infant Scene Perception Presented at the 2015 Biennial Meeting for the Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD 2015), Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Vernetti A, Smith TJ, & Senju A (2017). Gaze-contingent reinforcement learning reveals incentive value of social signals in young children and adults. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1850), 20162747 10.1098/rspb.2016.2747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanti G, Nadig A, Ozonoff S, & Rogers SJ (2008). What do children with autism attend to during imitation tasks? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 101(3), 186–205. 10.1016/j.jecp.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Celebi FM, Flink L, Greco G, Wall C, Prince E, … Shic F (2015). Interactive eye tracking for gaze strategy modification. Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, pp. 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Want SC, & Harris PL (2002). How do children ape? Applying concepts from the study of non-human primates to the developmental study of ‘imitation’ in children. Developmental Science, 5(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wass S, Porayska-Pomsta K, & Johnson MH (2011). Training attentional control in infancy. Current Biology, 21(18), 1543–1547. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb SJ, Neuhaus E, & Faja S (2017). Face perception and learning in autism spectrum disorders. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(5), 970–986. 10.1080/17470218.2016.1151059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherby AM, Woods J, Allen L, Cleary J, Dickinson H, & Lord C (2004). Early indicators of autism spectrum disorders in the second year of life. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(5), 473–493. 10.1007/s10803-004-2544-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J, Whiten A, & Singh T (2004). A systematic review of action imitation in autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(3), 285–299. 10.1023/B:JADD.0000029551.56735.3a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilms M, Schilbach L, Pfeiffer U, Bente G, Fink GR, & Vogeley K (2010). It’s in your eyes—using gaze-contingent stimuli to create truly interactive paradigms for social cognitive and affective neuroscience. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5(1), 98–107. 10.1093/scan/nsq024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]