Abstract

Objectives:

Investigating the frequency of apathy and disinhibition in patients clinically diagnosed with dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT) or behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) with neuropathology of either Alzheimer disease (AD) or frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD).

Methods:

Retrospective data from 887 cases were analyzed, and the frequencies of apathy and disinhibition were compared at baseline and longitudinally in 4 groups: DAT/AD, DAT/FTLD, bvFTD/FTLD, and bvFTD/AD.

Results:

Apathy alone was more common in AD (33%) than FTLD (25%), and the combination of apathy and disinhibition was more common in FTLD (43%) than AD (14%; P < .0001). Over time, apathy became more frequent in AD with increasing dementia severity (33%-41%; P < .006).

Conclusions:

Alzheimer disease neuropathology had the closest association with the neuropsychiatric symptom of apathy, while FTLD was most associated with the combination of apathy and disinhibition. Over time, the frequency of those with apathy increased in both AD and FTLD neuropathology.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, apathy, disinhibition, neuropsychiatric symptoms, apolipoprotein E4

Background

Apathy and disinhibition are among the most common behavioral disturbances of dementia. 1 -4 Although they constitute some of the key features in behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), they also occur in amnestic dementias of the Alzheimer type (DAT). 5 Although most patients with the DAT phenotype have Alzheimer disease (AD) neuropathology, 6 and most patients with the FTD phenotype have frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), 2,7 amnestic dementias can also be caused by atypical manifestations of FTLD, and behavioral dementia can also be caused by atypical manifestations of AD neuropathology. The extent to which underlying neuropathology influences the clinical expression of the 2 phenotypes remains unknown.

Previous studies reported that the loss of emotional reactivity (apathy) and disinhibition is more characteristic of clinical bvFTD than of DAT. 5,1 However, few studies analyzed the frequency of these behaviors in autopsy-confirmed cases. Also, prior studies 8,9 have not distinguished among patients who exhibited apathy alone, disinhibition alone or a combination of both symptoms. Finally, it remains unknown how the time course of these neuropsychiatric symptoms differs as a function of neuropathology.

In this study, we analyzed data from participants enrolled in the National Alzheimer Coordinating Center (NACC) database, clinically diagnosed with DAT or bvFTD who had been followed longitudinally and who had a primary neuropathologic diagnosis of either AD or FTLD without evidence of the other major neuropathology. Analyses addressed the relationship of neuropsychiatric symptoms with underlying neuropathology at initial assessment and over time. Also, we analyzed the relationship between the apolipoprotein E4 allele (APOE4) and neuropsychiatric symptoms since previous work had suggested that APOE4, a major genetic risk factor for AD, is associated with apathy. 10

Method

This is a retrospective analysis of data from cases followed longitudinally and with postmortem neuropathologic diagnosis from the NACC database. All cases had been examined during life with the Uniform Data Set (UDS), 11,12 a method for systematic data collection used across the 34 past and present Alzheimer Disease Centers (ADCs) funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA). Participants in the ADCs’ Clinical Cores receive in-person evaluations on a yearly basis until study withdrawal or death. Medical, psychiatric, and neurologic histories, a neuropsychological test battery, and research psychiatric and neurological examinations and questionnaires are among the data obtained. 11 Participants’ study partners also provide information to aid in clinical diagnosis. All participants had provided informed consent under the oversight of the institutional review board for each ADC, including precommitment to brain autopsy at the time of death for diagnosis, research use of tissue, and sharing of data.

Participants

Data collected by the NIA-funded ADCs and contributed to NACC between 2005 and 2013 were reviewed to identify cases with a clinical diagnosis of DAT or bvFTD at first visit and a postmortem neuropathologic diagnosis of AD or FTLD. From 2013 to the present, the method of coding postmortem diagnosis had changed, and so these cases were not included. Inclusion criteria resulted in an initial sample size of 1666 cases. Additional inclusion criteria were at least 2 visits at which the UDS was collected, full demographic data (sex, education, race, age of onset, age of death), APOE4 genotype, and completed Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q).

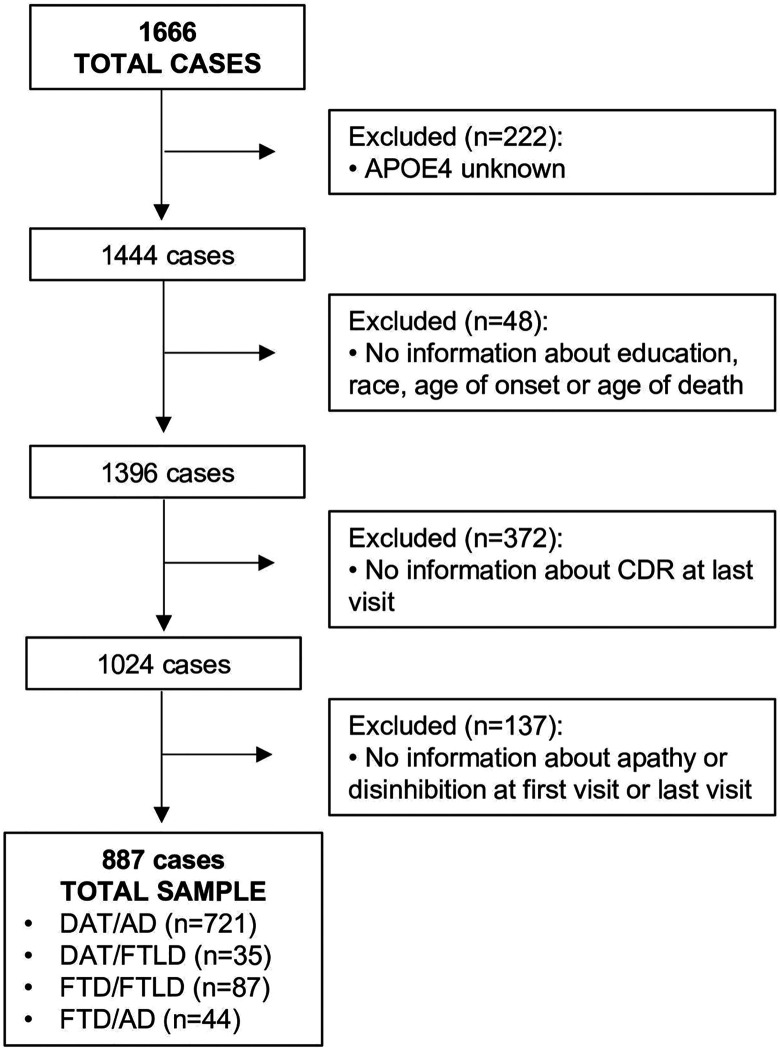

From the initial 1666 cases identified, the final number of cases meeting all criteria for the current analyses was a total of 887 (Figure 1), including 756 with clinical DAT and 131 with clinical bvFTD. After reviewing the neuropathologic diagnosis, these cases were divided into 2 neuropathologic groups, regardless of clinical diagnosis (AD, N = 765; and FTLD, N = 122) and also into 4 categories that considered both clinical dementia syndrome and postmortem neuropathologic diagnosis: DAT/AD (N = 721), DAT/FTLD (N = 35), bvFTD/FTLD (N = 87), and bvFTD/AD (N = 44).

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the participants excluded in the current study. From the original 1666 cases, 779 were excluded. APOE ∊4 indicates apolipoprotein ∊4 allele; bvFTD/AD, clinical behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia with Alzheimer disease pathology; bvFTD/FTLD, clinical behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia with frontotemporal lobar degeneration neuropathology; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale; DAT/AD, clinical dementia of the Alzheimer type with Alzheimer disease neuropathology; DAT/FTLD, clinical DAT with frontotemporal lobar degeneration neuropathology.

Clinical diagnostic criteria used by the Alzheimer centers had changed in 2011. Before 2011, the clinical diagnosis of dementia associated with AD had been assigned according to the NINCDS/ADRDA criteria 13 and, after that date, by updated criteria to reflect the distinction between clinical and neuropathologic phenotypes. 14 For the diagnosis of bvFTD, patients had primarily been diagnosed using the 1998 Consensus Criteria 3 prior to 2011. After 2011, participants were diagnosed clinically with updated criteria. 3,15 For the present study, we focused on bvFTD and excluded cases with primary clinical diagnosis of PPA, or any of the FTD motor variants, namely, corticobasal or progressive supranuclear palsy syndrome.

Neuropathological assessments are performed at each ADC using standardized criteria. Of the 887 cases, 765 had a primary diagnosis of Alzheimer pathology by either NIA-Reagan Criteria 6 or NIA-AA criteria 16,17,18 the remaining 122 cases had a primary diagnosis of some form of FTLD neuropathology. 19,20

Dementia severity, based on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR), was noted for the initial and final visits to determine whether neuropsychiatric symptoms were disease specific or related to general disease severity. The CDR is a global scale based on clinician judgment of functional level in 6 domains: memory, orientation; judgment and problem-solving; community affairs; home and hobbies; and personal care. 21 This scale yields a global score 22 used in this study: 0 = no dementia, 0.5 = questionable dementia, 1.0 = mild dementia, 2.0 = moderate dementia, 3.0 = severe dementia. 23

Neuropsychiatric Assessment

Information on neuropsychiatric symptoms had been collected for the UDS using the NPI-Q, 24 based on surveying caregivers/study partners for the frequency and severity of 12 behavioral and emotional symptoms. The scale has good content and concurrent validity 25 and has been used in studies to differentiate clinical DAT from bvFTD. 9

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic factors, APOE4 status, and CDR. Groups were compared on these variables using Fisher exact test or analysis of variance accounting for different variances across groups.

The frequency of apathy alone, disinhibition alone, the combination of both, or neither symptom was compared between pathologic diagnoses (AD vs FTLD) regardless of the clinical diagnosis, using χ2 goodness-of-fit analysis to test for equal frequencies across groups. The frequency of these symptoms was also analyzed within each of the 4 clinicopathologic groups (DAT/AD, DAT/FTLD, bvFTD/FTLD, and bvFTD/AD) to determine whether the clinical diagnosis modified the relationship. The CDR was compared among the 4 clinicopathologic groups using Fisher exact test.

Longitudinal changes in apathy, disinhibition, and both symptoms combined were investigated comparing the frequency of the neuropsychiatric symptoms longitudinally using McNemar test for unadjusted analyses and conditional logistic regression for comparisons adjusting for CDR.

Results

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in gender distribution, ethnicity, or years of formal education among the 4 groups. Mean ages at symptom onset, death, and the duration of disease differed across the groups, P < .0001. As expected, based on previous reports, 13,15 the reported age of onset was lower in patients with clinical bvFTD than with DAT. The median interval between baseline and last visit across all groups was 35.6 months with a range of 6.3 to 93 months.

Table 1.

Demographic Features of Patients in the Study Groups.

| Characteristics | DAT/AD | DAT/FTLD | FTD/AD | FTD/FTLD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 721) | (n = 35) | (n = 44) | (n = 87) | |

| Male (%)a | 55% | 54% | 61% | 10% |

| Caucasian, %a | 94% | 89% | 98% | 99% |

| Education, years, mean ± SEMa | 15.0 ± 0.12 | 14.6 ± 0.66 | 15.8 ± 0.47 | 15.2 ± 0.33 |

| Age at onset, years, mean ± SEMb | 71.9 ± 0.42 | 71.0 ± 1.74 | 61.2 ± 1.26 | 57.9 ± 1.08 |

| Age at death, years, mean ± SEMb | 81.5 ± 0.39 | 80.1 ± 1.68 | 79.3 ± 1.22 | 65.9 ± 1.07 |

| Duration of disease, monthsb | 115.2 ± 1.8 | 108.7 ± 7.31 | 97.4 ± 6.3 | 96.6 ± 6.7 |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; bvFTD/AD, clinical behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia with AD neuropathology; bvFTD/FTLD, clinical behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia with frontotemporal lobar degeneration neuropathology; DAT/AD, clinical dementia of the Alzheimer type with Alzheimer disease neuropathology; DAT/FTLD, clinical DAT with frontotemporal lobar degeneration neuropathology.

aNo significant differences.

b P < .0001.

The 4 clinicopathologic groups had similar levels of dementia severity compared with one another at baseline (P = .52) and at final (P = .60) visits as demonstrated by the distribution of participants within each level of the CDR. At baseline, most had CDR 0.5 to 1: DAT/AD = 72%, DAT/FTLD = 74%, bvFTD/FTLD = 69%, and bvFTD/AD = 68%. In the last visit prior to death, most of the participants had CDR = 3: DAT/AD = 44%, DAT/FTLD = 46%, bvFTD-FTLD = 48%, and bvFTD/AD = 50%. Thus, as anticipated, dementia severity increased in all groups over time.

Comparison of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Versus Neuropathologic and Clinicopathologic Groups at Baseline

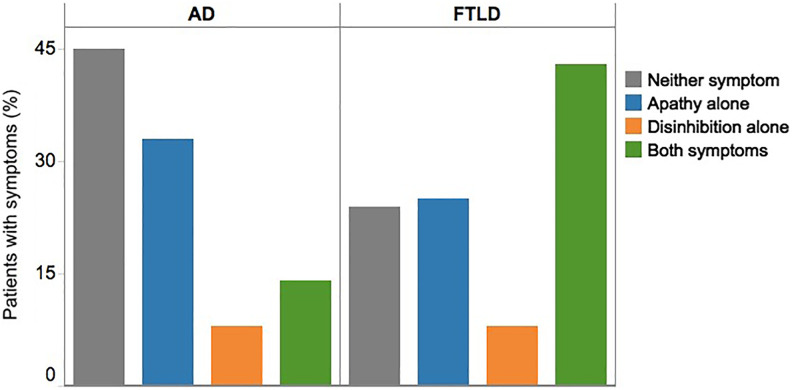

At baseline, the distribution of symptoms differed by neuropathologic diagnosis (P < .0001). The most common symptom with AD neuropathology was apathy alone (33%) regardless of clinical presentation (ie, DAT vs bvFTD) (Figure 2). Disinhibition alone was related to AD and FTLD in very low frequency (both 8%). Frontotemporal lobar degeneration was more frequently associated with the contemporaneous expression of both symptoms (44%).

Figure 2.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms by AD and FTLD neuropathology at initial visit. In patients with AD and FTLD neuropathology, the distribution of symptoms was significantly different (P < .0001). AD indicates Alzheimer disease neuropathology; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration neuropathology.

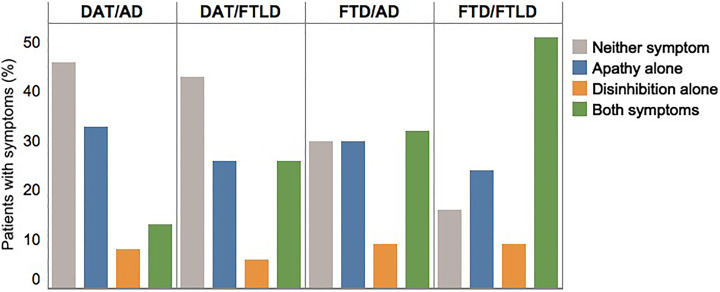

The distribution of symptoms also differed by clinicopathologic groups (P < .0001). The frequency of both symptoms combined was higher in the bvFTD/AD group than in the DAT/AD group (32% vs 13%, respectively) (Figure 3). In addition, the comparison of the bvFTD/AD and bvFTD/FTLD groups revealed that the frequency of both symptoms combined was higher when the neuropathology was FTLD (32% vs 51%, respectively). Thus, the highest association between the combination of apathy and disinhibition was observed with clinical–pathological concordance for bvFTD with FTLD. This association, however, may be affected by the fact that these symptoms are incorporated into the clinical diagnosis of the bvFTD syndrome.

Figure 3.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms by clinicopathologic groups at initial visit. The distribution of neuropsychiatric symptoms across the clinicopathologic groups was significantly different (P < .0001). bvFTD/AD indicates clinical behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia with Alzheimer disease neuropathology; bvFTD/FTLD, clinical behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia with frontotemporal lobar degeneration neuropathology; DAT/AD, clinical dementia of the Alzheimer type with Alzheimer disease neuropathology; DAT/FTLD, clinical DAT with frontotemporal lobar degeneration neuropathology.

Comparison of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Within Neuropathologic and Clinicopathologic Groups Longitudinally

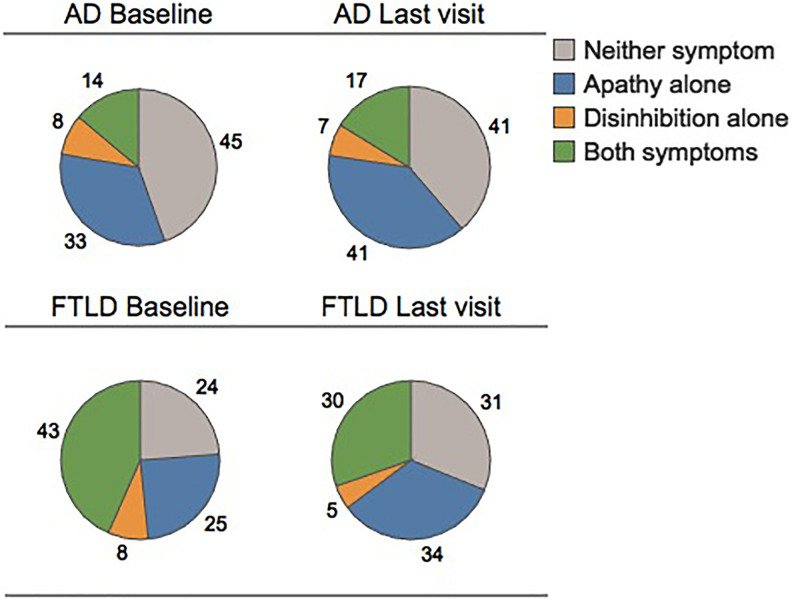

Longitudinally, we found that in AD neuropathology, the frequency of individuals with apathy alone increased from 33% to 41% at last visit prior to death (P < .0006) (Figure 4). The frequency of those with disinhibition alone was similar at baseline and last visit (P = .24) and the frequency of individuals with the combination of both symptoms increased (P = .048). In cases with FTLD neuropathology, the frequency of those with apathy alone increased, but not significantly (P = .09). The frequency of cases with disinhibition was similar at first and last visit (P = .32). In contrast, the frequency of those with both symptoms decreased (P = .018).

Figure 4.

The proportion of neuropsychiatric symptoms within neuropathologic diagnostic groups at first and last visits. Neuropsychiatric symptoms were analyzed at the first and last clinical visits. The frequency of apathy alone increased for cases with AD (P < .0006) and FTLD (P = .09). While the frequency of both symptoms increased for cases with AD (P = .048) and decreased for cases with FTLD (P = .018). AD indicates Alzheimer disease neuropathology; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration neuropathology.

Longitudinal comparisons of the clinicopathologic groups revealed that in the DAT/AD groups, the apathy rate at baseline was 33% and increased to 41% at last visit (P < .002). The frequency of those with disinhibition alone was similar over this interval (P = .32) and the frequency of those with a combination of apathy and disinhibition increased from 13% at baseline to 17% at last visit (P = .009). In cases with bvFTD/FTLD, the frequency of apathy alone and disinhibition alone remained the same from baseline to last visit (apathy alone: P = .47; disinhibition alone: P = .41). The frequency of cases with both symptoms was 51% at baseline and decreased to 33% at last visit (P = .01). In discordant cases, we observed a tendency for increasing apathy over time (DAT/FTLD: P = .052; FTD/AD: P = .059).

Comparison of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms to APOE4

The APOE status did not relate to the occurrence of symptoms in patients with either AD (P = .15) or FTLD neuropathology (P = .54).

Discussion

This study investigated whether different types of postmortem neuropathology in patients with clinical diagnosis of DAT or bvFTD were differentially related to neuropsychiatric symptoms of apathy and disinhibition. A retrospective analysis using data from a national database, of cases clinically diagnosed with DAT or bvFTD with postmortem AD or FTLD neuropathology, showed that apathy and disinhibition had distinctive associations with the neuropathologic diagnosis. Apathy was largely associated with AD neuropathology, while the combination of apathy and disinhibition was largely associated with FTLD neuropathology, regardless of clinical diagnosis. Disinhibition alone, contrary to common assumptions about its association with bvFTD, occurred in very low frequency with either AD or FTLD neuropathology. Finally, these diseases were also associated with distinctive longitudinal course of the neuropsychiatric symptoms: the frequency of apathy increased in patients with AD neuropathology, while the frequency of disinhibition over time remained low for those with either AD or FTLD neuropathology.

The significance of neuropsychiatric symptoms as a precursor to DAT has been frequently noted, 26 and The International Society to Advance Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment – Alzheimer’s Association group has proposed a checklist of Mild Behavioral Symptoms (MBI-C) to capture these symptoms as a precursor to cognitive decline. 26 Although the MBI-C is an important addition to our clinical valuation instruments, it awaits further validation against neuropathologic diagnoses.

Indifference and disinhibition have been reported in a significant number of patients with DAT. 4,27,28 These studies, however, lacked autopsy confirmation. In our sample, most of the patients with DAT/AD presented with neither behavioral symptom, but when one symptom was present, it was apathy alone. We demonstrate that apathy alone was highly associated with AD neuropathology but that the combination of apathy and disinhibition was more frequently associated with FTLD. We also found that the neuropathologic diagnosis of AD is most commonly associated with apathy alone not only in an amnestic dementia (DAT) but also in a dementia in which the prominent symptoms are behavioral (ie, bvFTD) rather than amnestic.

In a previous study, 8 no difference was reported in the frequency of disinhibition alone or apathy alone between clinical bvFTD groups with either FTLD or AD neuropathology. Our results replicated this absence of a group difference in the frequency of disinhibition alone. In contrast to the previous study’s findings, however, we report distinct differences between the clinical presentation of apathy alone and the underlying neuropathology. In the present study, clinical bvFTD was more frequently associated with apathy alone when the neuropathology was AD and associated with the combination of both symptoms when the neuropathology was FTLD.

Most studies of behavioral symptoms in bvFTD and DAT have been based on clinically diagnosed samples without autopsy confirmation. Some studies have shown that apathy, disinhibition, impulsivity, and inappropriateness are more likely to be associated with bvFTD than with DAT. 29 -33 Other studies 5,9 using the Frontal Behavioral Inventory (FBI) reported indifference and apathy as the most frequent negative symptoms in clinical bvFTD, while disinhibition, inappropriateness, and impulsivity were among the most significant positive symptoms. For all symptoms, scores on the FBI were higher in bvFTD than in DAT. Yet another study 9 analyzed the neuropsychiatric profiles in patients with clinical DAT and bvFTD, with either FTLD or AD neuropathology, and found that the clinical diagnosis of bvFTD was more frequently associated with apathy and disinhibition. However, that study compared patients with DAT/AD to patients with clinical bvFTD, regardless of neuropathology. 16

Patients with dementia and noncognitive, behavioral symptoms are often mistaken for having psychiatric disease. Woolley et al analyzed 252 participants, including 69 with a clinical diagnosis of bvFTD and 65 with probable AD and reported that 28.2% of patients with a neurodegenerative disease received a prior psychiatric diagnosis. 17 Depression was the most common psychiatric diagnosis in all groups. This study showed that those with bvFTD are at highest risk of misdiagnosis because they received a prior psychiatric diagnosis significantly more often (52.2%) than patients with AD (23.1%). Also, the study showed that due to behavioral symptoms, patients with bvFTD often initially received diagnoses of major depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, or schizophrenia. 17 When persons with bvFTD and other dementias receive psychiatric instead of neurodegenerative diagnoses, treatment is delayed and there can be considerable psychosocial turmoil.

In contrast to a prior study that had reported an association between apathy and APOE4, we did not find a relationship between APOE4 and neuropsychiatric symptoms in either AD or FTLD neuropathology. However, unlike the present study, the prior study was based only on clinical diagnosis and lacked autopsy confirmation. 10

The present study has potential limitations. Information about neuropsychiatric symptoms was collected from informants (caregivers and other types of study partners) and was not based on direct, objective measurement. Secondly, consensus research criteria for the clinical diagnosis changed during the period of data accumulation, and although that change preserved many of the features of the original criteria, this could have influenced the clinical diagnosis.

In summary, in the present study, AD neuropathology was more frequently associated with apathy alone, while FTLD neuropathology was more frequently associated with the combination of apathy and disinhibition, regardless of the clinical diagnosis. Disinhibition alone was not helpful for differentiating between AD and FTLD. Over time, symptoms of apathy affected a larger proportion of individuals with either type of neuropathology. Since neuropsychiatric symptoms appear to have different associations with AD and FTLD neuropathology, 34,35 the occurrence of these symptoms can be incorporated in the differential diagnosis in order to increase clinical diagnostic accuracy.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported in part by Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center grant [P30AG013854] to Northwestern University (Mesulam, PI), and the NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant [U01 AG016976]. A.W.R. is supported by grants from the NIH: AG013854, R01 DC008552, NS075075, and AG045571. S.W. is supported by grants from the NIH: AG013854, DC008552, AG045571, AG016976, and AG010483 and is an investigator in clinical trials of antidementia drugs from Eli Lilly and Company.

ORCID iD: Letizia G. Borges  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6154-6571

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6154-6571

References

- 1. Bathgate D, Snowden JS, Varma A, Blackshaw A, Neary D. Behaviour in frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103(6):367–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neary D, Snowden JS, Northen B, Goulding P. Dementia of frontal lobe type. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51(3):353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cummings JL, Victoroff JI. Noncognitive neuropsychiatric syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1990;3(2):140–158. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kertesz A, Davidson W, Fox H. Frontal behavioral inventory: diagnostic criteria for frontal lobe dementia. Can J Neurol Sci. 1997;24(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ball MJ, Braak H, Coleman P. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(suppl 4):S1–S2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the work group on frontotemporal dementia and pick’s disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(11):1803–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mendez MF, Joshi A, Tassniyom K, Teng E, Shapira JS. Clinicopathologic differences among patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2013;80(6):561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leger GC, Banks SJ. Neuropsychiatric symptom profile differs based on pathology in patients with clinically diagnosed behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;37(1-2):104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Monastero R, Mariani E, Camarda C, et al. Association between apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele and apathy in probable Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, et al. The Uniform Data Set (UDS): clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer Disease Centers. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20(4):210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1984;34(7):939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain 2011;134(Pt 9):2456–2477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 2012;123(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woolley JD, Khan BK, Murthy NK, Miller BL, Rankin KP. The diagnostic challenge of psychiatric symptoms in neurodegenerative disease: rates of and risk factors for prior psychiatric diagnosis in patients with early neurodegenerative disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(2):126–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, et al. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(1):5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bigio E. Making the diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. ArchPathol Lab Med. 2013;137(3):314–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry 1982;140:566–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O’Bryant SE, Waring SC, Cullum CM, et al. Staging dementia using Clinical Dementia Rating Scale sum of boxes scores: a Texas Alzheimer’s Research Consortium Study. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(8):1091–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(suppl 1):173–176; discussion 177–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the neuropsychiatric inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ismail Z, Smith EE, Geda Y, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(2):195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumar A, Koss E, Metzler D, Moore A, Friedland RP. Behavioral symptomatology in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1988;2(4):363–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R. Psychiatric phenomena in Alzheimer’s disease. IV. disorders of behaviour. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kertesz A, Nadkarni N, Davidson W, Thomas AW. The frontal behavioral inventory in the differential diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000;6(4):460–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levy ML, Miller BL, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, Craig A. Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementias. Behavioral distinctions. Arch Neurol. 1996;53(7):687–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hirono N, Mori E, Tanimukai S, et al. Distinctive neurobehavioral features among neurodegenerative dementias. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;11(4):498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nagahama Y, Okina T, Suzuki N, Matsuda M. The Cambridge Behavioral Inventory: validation and application in a memory clinic. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2006;19(4):220–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mendez MF, Perryman KM, Miller BL, Cummings JL. Behavioral differences between frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a comparison on the BEHAVE-AD rating scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1998;10(2):155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tekin S, Mega MS, Masterman DM, et al. Orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex neurofibrillary tangle burden is associated with agitation in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2001;49(3):355–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zamboni G, Huey ED, Krueger F, Nichelli PF, Grafman J. Apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia: insights into their neural correlates. Neurology. 2008;71(10):736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]