Abstract

For many men, prostate cancer is an indolent disease that, even without definitive therapy, may have no impact on their quality of life or overall survival. However for those men who are either diagnosed with or eventually develop metastatic disease, prostate cancer is a painful and universally fatal disease. Testosterone-lowering hormonal therapy may control the disease for some time, but patients eventually develop resistance and progress clinically. At this point, only docetaxel has been shown to improve survival, so clearly additional therapeutic options are needed. Angiogenesis inhibition is an active area of clinical research in prostate cancer. Without angiogenesis, tumors have insufficient nutrients and oxygen to grow larger than a few millimeters and are potentially less likely to metastasize. In prostate cancer in particular, angiogenesis plays a significant role in tumor proliferation, and markers of angiogenesis appear to have prognostic significance. Several different compounds have been developed to inhibit angiogenesis, including monoclonal antibodies, multitargeted kinase inhibitors, and fusion proteins. In addition, more traditional agents may also have an impact on angiogenesis. Trials studying antiangiogenic agents have been conducted in localized and advanced prostate cancer. There are several large, ongoing phase III trials in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. The findings of these and future studies will ultimately determine the role of angiogenesis inhibitors in the treatment of prostate cancer.

Keywords: Antiangiogenesis, prostate cancer, bevacizumab, multikinase inhibitors, fusion proteins

CURRENT STATE OF PROSTATE CANCER THERAPY

Despite advances in medical oncology over the last decade, prostate cancer remains a commonly diagnosed and potentially lethal disease. With almost 200,000 new diagnoses annually and more than 27,000 deaths, prostate cancer treatments require continued investigation and enhancement [1]. In spite of aggressive prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening, 20% to 40% of patients treated with definitive surgery or radiation will have disease recurrence, regardless of the type of primary intervention [2-5]. Patients with metastatic disease often receive sequential hormonal manipulations until symptomatic metastatic disease develops [6]. In 2004, docetaxel became the first chemotherapeutic agent approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for metastatic CRPC based on an improvement in survival compared to mitoxantrone and prednisone [7, 8]. Since that time, studies have attempted to improve on the standard docetaxel regimen, but without success. Given the clinical benefit demonstrated with angiogenesis inhibitors in other cancers and the sound scientific rationale for its use in prostate cancer, angiogenesis inhibition has become an active area of clinical research in the treatment of prostate cancer.

ANGIOGENESIS IN THE TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT

Angiogenesis is a vital component of fetal development and wound healing, and may also play an important role in tumor progression. The concept that tumors require neovascularization to support their growth was first postulated by Dr. Judah Folkman in 1971 [9]. Since that time, our understanding of the role of angiogenesis in cancer has expanded. Tumors that are < 2 mm are likely able to acquire oxygen and other nutrients through simple diffusion from established capillaries. For tumors to grow beyond this rudimentary size, they need to develop their own vasculature. It is postulated that tumors undergo a transformation, or “angiogenic switch,” at some point in their development [10]. This angiogenic switch occurs at different points in tumor progression, based on tumor type and microenvironment. The end result is tumor neovascularization [10, 11]. Once tumors are able to recruit additional blood vessels, the increased oxygen and nutritional support can lead to significant tumor growth and the potential for metastasis.

Tumor angiogenesis begins on a genetic level. Hypoxia increases as tumors outgrow their existing blood supply, resulting in proangiogenic genetic expression [12]. This genetic activation leads to the production of growth factors that can enhance vasculature development, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietin-1 (ANG1), and placental growth factor (PlGF) [13, 14]. Although VEGF plays a primary role in angiogenesis and can instigate the process on its own, in its absence, ANG1 and PlGF can lead to vascular development, a fact that may have therapeutic implications as angiogenesis inhibition strategies are developed [15].

As proangiogenic factors increase in the tumor microenvironment, existing capillary or post-capillary vasculature dilates and becomes more permeable, allowing for the efflux of proteins that lay down the provisional architecture for new vessels. Circulating or bone marrow-derived endothelial cells are recruited to these areas, forming a migrating column which ultimately becomes neovasculature [16, 17]. Several aspects of this process are still poorly understood, but the primary role of VEGF is apparent, and this factor is most commonly employed among different tumor types.

The resulting tumor neovasculature may be different from the vessels that serve the body’s normal tissue. The new tumor-induced vessels are more tortuous and erratic in design and may have dead ends that do not lead to the tumor. Due to high levels of VEGF, they are often very permeable. A lower number of stromal cells than are present in normal vasculature and the presence of tumor cells within the new vessel walls add to the inefficient, leaky nature of tumor neovasculature [18-21].

As with any complex biological process, angiogenesis can potentially be blocked at several points in an effort to limit tumor neovascularization. Such blocking mechanisms include decreasing endothelial cell proliferation, inhibiting proangiogenic factors through the use of neutralizing antibodies and fusion proteins, or intervening in signal transduction after proangiogenic factors bind to extracellular receptors (Table 1) [22]. The most studied proangiogenic factor is VEGF, which includes VEGF-A, -B, -C, -D, -E, and -F. VEGF-A has the most significant function in tumor angiogenesis [22]. VEGF-A binds to 3 different VEGF receptors: VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3. VEGFR-2 is expressed mainly by endothelial cells and plays a vital role in tumor angiogenesis [23, 24].

Table 1.

Mechanism of Angiogenesis Inhibition by Targeted Agents

| Modality | Mechanism of Inhibition |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal antibodies |

|

| Fusion protein |

|

| Multitargeted receptor kinase inhibitors |

|

VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor.

RATIONALE FOR ANTIANGIOGENIC THERAPY IN PROSTATE CANCER

Initial preclinical data indicate that angiogenesis inhibitors decrease tumor growth in both in vitro and in vivo models [25-27], Further clinical data demonstrate the importance of angiogenesis in prostate cancer proliferation. Proangiogenesis serum factors are increased in patients with prostate cancer relative to healthy patients. Another way to assess angiogenesis activity is to determine the relative microvessel density in patients with prostate cancer. Increased microvessel density has been correlated with increased serum levels of proangiogenesis factors in prostate cancer patients [28]. Not surprisingly, microvessel density is increased in prostate adenocarcinoma compared with adjacent normal prostate tissue and prostate tissue that has undergone benign hypertrophy. Furthermore, patients with metastatic disease have higher microvessel density than patients with localized disease and no metastatic lesions [29].

Angiogenic activity may also have prognostic value in prostate cancer patients. A negative correlation has been seen between survival and patients with higher VEGF levels in both serum and urine [30, 31]. A study of over 1,000 men with prostate cancer suggested that microvessel density at the time of diagnosis was also prognostic in terms of overall survival [32]. This finding is consistent with previous data indicating that microvessel density correlates with high-grade primary tumors [29]. Although these findings are too preliminary to be useful in a clinical context, they demonstrate the potential influence of angiogenesis on disease progression and reveal the potential therapeutic benefit of angiogenesis inhibition in prostate cancer.

MECHANISM OF ACTION

The tumor microenvironment is greatly influenced by the erratic vasculature produced by the tumor’s proangiogenic effects. The end result is heterogeneous blood flow to different areas of the microenvironment, leading to varying degrees of hypoxia. This may actually favor tumor growth, as there is decreased chemotherapy perfusion to the center of the tumor. In addition, diffuse hypoxia may decrease the local effectiveness of immune cells and radiationbased therapies [33, 34]. Also, central areas of the tumors often have high interstitial pressure that further decreases chemotherapy penetration into the tumor and may result in an efflux of potentially metastatic cells into the circulation or lymphatics [35].

Paradoxically, the ultimate therapeutic mechanism of angiogenesis inhibition may not consist of decreasing blood flow to the tumor to starve it of oxygen and other vital nutrients. Although angiogenesis inhibitors may eliminate a small number of nascent vessels, emerging data suggest that the true benefit of these treatments may actually he in improved blood flow to the tumor [36-38]. Besides eliminating some inefficient vessels, angiogenesis inhibitors may also constrict vessels and decrease their permeability, thereby increasing blood flow to the tumor microenvironment [39, 40]. With the resulting stabilized interstitial pressure dynamics, chemotherapy and targeted molecular inhibitors may penetrate more regions of the tumor. Furthermore, improved tumor oxygenation may enhance the effects of radiation and immunotherapy.

Regardless of the ultimate mechanism of action, there is sound scientific rationale for employing angiogenesis inhibitors in the treatment of prostate cancer. Many antiangiogenesis strategies have been developed and investigated in an effort to improve the outcome for prostate cancer patients, with some intriguing results (Table 2).

Table 2.

Important Trials in the Clinical Development of Angiogenesis Inhibitors in Prostate Cancer

| Disease state | n | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| mCRPC (chemotherapy-naïve) | 15 | Initial phase II trial of bevacizumab in prostate cancer demonstrated tolerability. (Ref. #51) |

| mCRPC (chemotherapy-naïve) | 17 | A combination of bevacizumab, docetaxel, and estramustine demonstrated the benefits of chemotherapy and angiogenesis inhibition in prostate cancer. Overall survival was 21 months.1 |

| mCRPC (chemotherapyrefractory and naïve) | 46 | A trial of sorafenib suggested efficacy of angiogenesis inhibition in docetaxel-refractory CRPC. Also noted were altered PSA kinetics post-therapy that were incongruent with clinical responses. (Ref. #69) |

| mCRPC (chemotherapy-naïve) | 60 | A combination of antiangiogenesis inhibitors (thalidomide and bevacizumab) plus docetaxel demonstrated significant clinical responses, including 71% of patients with a > 80% PSA decline and median time to progression of 18.2 months.2 |

| mCRPC (chemotherapy-naïve) | Results pending | A phase III trial of docetaxel with and without bevacizumab that will determine the drug’s role in mCRPC therapy. This trial has completed accrual and results are expected by early 2010. (Ref. #53) |

MONOCLONAL ANTIBODIES

Bevacizumab (Avastin®; Genentech, Inc., South San Francisco, CA) is the most studied antiangiogenic agent in clinical trials. It is a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody developed from a murine monoclonal antibody targeting human VEGF ligand. The antibody consists of 93% human protein sequences; the remaining 7% is a murine protein sequence residing chiefly in the complementarydetermining region [41-43]. Bevacizumab specifically recognizes and binds to all major isoforms of VEGF-A, making them unable to bind to VEGF receptors and thereby incapable of perpetuating the angiogenesis signal transduction cascade.

Initial preclinical studies demonstrated the effects of a murine monoclonal antibody targeting VEGF on several human cancer cell lines in vivo. These studies were the foundation of the subsequent development of bevacizumab and its ultimate use in the treatment of multiple tumor types [26, 41, 44]. In the United States, the FDA has approved bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic colon, breast, and non-small cell lung cancer [45-49]. In addition, it was recently approved as a single agent in glioblastoma [50]. Promising studies also demonstrate the potential of bevacizumab in prostate cancer.

As has often been the case in clinical trials in other tumor types, the initial phase II study with bevacizumab alone did not result in significant clinical responses. In this study, 15 patients with metastatic CRPC were treated with 10 mg/kg of bevacizumab every 14 days for 6 total treatments. Half of the 14 evaluable patients had disease progression at 70 days. Only 4 patients had PSA declines, none > 50%. Common toxicities included fatigue, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia [51].

This trial was followed by Cancer and Leukemia Group B 90006 for metastatic CRPC, in which bevacizumab (15 mg/kg every 21 days) was combined with docetaxel (70 mg/m2 every 21 days) and estramustine (280 mg on days 1 to 5 of the 21-day cycle). In this trial, there appeared to be better antitumor activity compared to trials where patients were treated with docetaxel and estramustine without bevacizumab. PSA declines of > 50% were seen in 81% of patients, with time to progression of 9.7 months and an overall survival of 21 months [52].1 The subsequent approval of docetaxel and prednisone as the standard treatment for metastatic CRPC led to the phase III investigation of docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 21 days vs. docetaxel 75 mg/m2 and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 21 days. Both arms included prednisone 5 mg twice a day. The study completed accrual in December 2007 and results may be available by late 2009. The study was powered to detect a 25% improvement in overall survival in the bevacizumab arm [52, 53].

As oncologists await definitive phase III results in frontline metastatic CRPC, bevacizumab is also being investigated in other disease states. One phase II trial investigated metastatic CRPC patients who had progressed on docetaxel. Patients were re-treated with docetaxel at 60 mg/m2 combined with bevacizumab at 10 mg/kg in a 3-week regimen. Preliminary findings were encouraging, with 3 patients having objective responses and 11 of 20 patients enrolled having a > 50% decline in PSA (7 patients had a > 50% decline on previous docetaxel, while 4 did not have substantial previous PSA responses) [54].

Intriguing findings came out of a trial performed in patients with a rising PSA after initial definitive therapy, but without metastatic disease. The treatment combined bevacizumab (10 mg/kg) with the cellular-based therapeutic cancer vaccine sipuleucel-T (Provenge®; Dendreon, Seattle, WA) [56]. Sipuleucel-T has recently been shown to improve survival when compared to placebo in a phase III trial in advanced disease [55, 56]. A total of 3 sipuleucel-T infusions were given over 4 weeks. Bevacizumab was given every 14 days until disease progression. The rationale for the combination arose from preclinical data suggesting that VEGF may inhibit immune (dendritic) cell function in the tumor microenvironment, and that VEGF inhibitors such as bevacizumab may prevent such immune suppression, leading to enhanced immune responses against the tumor [57-59]. The preclinical data also suggested that improved profusion increased immune cell trafficking to the tumor. In the sipuleucel-T/bevacizumab trial, median PSA doubling time increased from 6.9 months on-study to 12.7 months (P = 0.01). Nine of 20 patients had PSA declines ranging from 6% to 72%, and all evaluable patients demonstrated specific immune responses [55]. These provocative preliminary data indicate that follow-up evaluations of vaccines plus antiangiogenic therapy, perhaps in combination with chemotherapy, may be warranted. Other clinical investigations of antiangiogenic agents are ongoing in early disease states, including combinations with chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or radiation.2,3

Another strategy currently being investigated is the use of fully humanized monoclonal antibodies to target the VEGF receptor in order to diminish endothelial cell proliferation, and thus angiogenesis [60]. Phase I studies of a potent anti-VEGFR-2 antibody, IMC-1121B, were well tolerated, with observed toxicities including anorexia, vomiting, fatigue, insomnia, depression, and anemia [61]. A phase II study is currently enrolling docetaxel-resistant, metastatic CRPC patients and evaluating IMC-1121B in combination with mitoxantrone and prednisone [62].

MULTITARGETED RECEPTOR KINASE INHIBITORS

After binding to serum VEGF, the cellular receptors VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3 initiate a signal transduction cascade that ultimately leads to epithelial cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. These VEGF receptors are kinases that activate the downstream PI3-K/AKT pathway and components of the RAF/MEK/ERK pathway [63]. Blocking these cellular receptors within the cell could prevent or impair the proliferative and angiogenic downstream effects of VEGF binding. Several such inhibitory agents have been investigated in the treatment of prostate cancer and are FDA-approved in the treatment of other cancers.

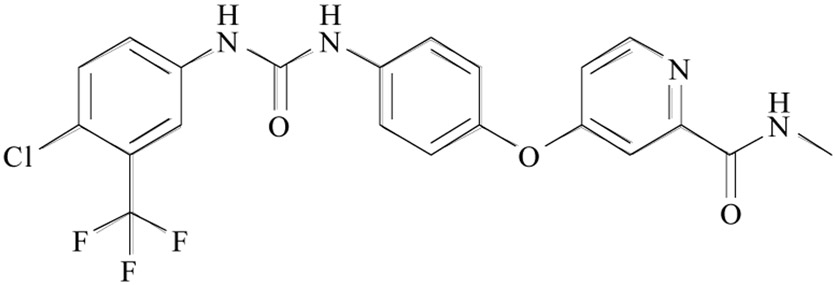

Sorafenib (Nexevar®; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc., Wayne, NJ) is a bi-aryl urea agent (see Fig. 1) that inhibits the activity of multiple tyrosine kinases, including those on the intracellular domain of VEGF-2 and VEGF-3. Sorafenib has been extensively studied in solid tumors and is FDA-approved as a secondline agent in metastatic clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma [64]. Several phase II trials with sorafenib have been conducted in patients with prostate cancer. A multicenter trial conducted by the Central European Society for Anticancer Drug Research enrolled a heterogeneous population of chemotherapy-naïve CRPC patients, 13% of whom had no metastatic disease. Sorafenib was administered at a dose of 400 mg twice daily. Median time to progression was 8 weeks. At one year, 68% of patients were still alive and 13% were progression-free. Common toxicities included fatigue, diarrhea, and dermatologic reactions [65]. Two other trials conducted in metastatic CRPC patients demonstrated similar findings [66, 67].

Fig. (1).

Sorafenib

Another trial of sorafenib was conducted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in metastatic CRPC patients. Of the 46 patients enrolled, 33 had been previously treated with chemotherapy. Although time to progression was found to be similar to that observed in previous trials, median overall survival was 18.3 months. Toxicities were generally as anticipated; however, some of the dermatologic (hand-foot) reactions were significant and may have been associated with cumulative dose [68-70]. An interesting finding in these trials was that while sorafenib actually increased PSA levels in patients, this increase was not necessarily related to increased tumor volume. Preclinical studies confirmed that the agent actually led to increased secretion of PSA by prostate cancer cells on a percell basis [69]. The NCI trial altered its progression criteria in the midst of the trial, which could account for the improved clinical benefit relative to other studies that used strict PSA progression criteria and therefore discontinued the agent sooner. In light of these findings, future trials with sorafenib and similar agents should include progression criteria that do not include PSA. Trials are currently investigating sorafenib in early-stage disease and in combination with chemotherapy [71-73].

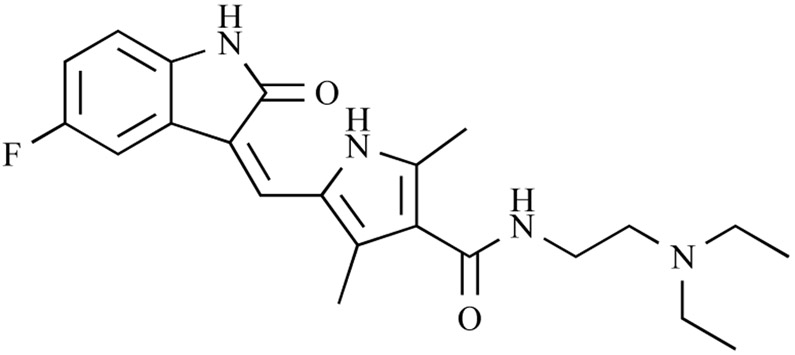

Another FDA-approved agent that has been investigated in the treatment of prostate cancer is sunitinib malate (Sutent®; Novartis, East Hanover, NJ), see Fig. (2). Also approved for the first-line treatment of metastatic clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma, this molecular inhibiting agent has broad activity against all 3 VEGF receptors [74, 75]. One phase II study enrolled 34 patients, half of whom were chemotherapy-naïve patients with metastatic CRPC and the other half were metastatic CRPC patients who had progressed on docetaxel. The dosing schedule was 50 mg/day in 6-week cycles of 4 weeks of treatment, then 2 weeks off. Among patients enrolled, 41% had PSA declines; one patient in each group had a PSA decline > 50%. Nineteen of 34 patients had stable disease after 12 weeks. Common observed side effects were nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, and significant levels of myelosuppression. Results indicated that serum VEGFR-2 decreased while on sunitinib, but increased when the drug was stopped, suggesting evidence of a VEGFR blockade in study patients [76].

Fig. (2).

Sunitinib

A second trial assessed sunitinib in metastatic CRPC patients who had progressed on 1 to 2 previous chemotherapy regimens. Nineteen patients were enrolled, with a median progression of 2.8 months. Four patients had PSA declines of ≥ 30%. Again, myelosuppression was a significant toxicity, a side effect that could complicate potential chemotherapy combinations in future studies.4 Nonetheless, trials evaluating sunitinib in prostate cancer are accruing in both early- and late-stage disease in combination with chemotherapy [77, 78].

Cediranib (Recentin®; AstraZeneca, London, UK) is another agent that inhibits the tyrosine kinases of VEGF receptors. This indole-ether quinazoline compound has activity against all 3 VEGF receptors, but is most potent against VEGFR-2, which may have the greatest role in tumor propagation [79]. Phase I studies suggested a safe dose level of 45 mg/day, but 20 mg/day was the recommended dose in patients with metastatic CRPC based on a subset of patients. Toxicities included hypertension, diarrhea, fatigue, vomiting, myalgia, and prolonged QTc complexes on ECG [80, 81]. Preliminary studies have indicated a discordance between clinical response and PSA, similar to those described with sorafenib [69].5 Preliminary findings from a phase II study in docetaxel-resistant metastatic CRPC are encouraging, with 13 of 23 evaluable patients having decreases in soft tissue lesions, 4 of which meet criteria for partial responses.5 If these findings remain consistent in the phase II study, cediranib may warrant further investigation, perhaps in combination with docetaxel or in an earlier disease state.

FUSION PROTEIN

A fusion protein is similar to a monoclonal antibody in function, but not in the formulation process. Like monoclonal antibodies, fusion proteins function as a decoy to bind ligands such as VEGF, preventing them from binding to receptors and initiating a signaling cascade. Monoclonal antibodies are generated by another animal, usually a mouse, after exposure to a human protein. After significant processing, these xenographic antibodies can be “humanized” by replacing portions of the antibody with human antibody components, resulting in a more tolerable antibody with minimal side effects. Fusion proteins are generated entirely from human molecules, often through the binding of the Fc portion of an IgG1 human antibody to molecules similar to the binding domain of a receptor. Since fusion proteins are entirely human, they often have more favorable side effect profiles and pharmacokinetics [82].

VEGF Trap (Aflibercept®; Sanofi Aventis, Paris, France and Regeneron, Tarrytown, New York), a human fusion protein developed as an antiangiogenic agent, binds with great affinity to VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and another prominent angiogenesis factor, PlGF. In preclinical models, VEGF Trap decreased microvessel density and tumor size, as well as the size and number of metastases [83-85]. A phase I study demonstrated tolerability, with major side effects including hypertension, proteinuria, leucopenia, and thrombosis.6 Based on promising phase II data in solid tumors, a phase III trial is randomizing approximately 1,200 metastatic CRPC patients to either VEGF Trap in combination with standard docetaxel and prednisone or standard docetaxel and prednisone alone [86].

OTHER AGENTS WITH ANTIANGIOGENIC PROPERTIES

Several agents influence angiogenesis, although their exact mechanisms are poorly understood. One such agent is thalidomide (Thalomid®; Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ), whose antiangiogenic properties led to birth defects in Europe 5 decades ago [87-89]. Preliminary evidence from in vitro and in vivo animal models suggests that thalidomide may have proapoptotic effects or may reduce angiogenic factors in patients with prostate cancer [90]. Thalidomide has overcome its ignominious history to become an FDA-approved treatment for multiple myeloma; investigations are ongoing in prostate cancer [91].

An open-label, phase II, randomized trial of thalidomide in prostate cancer found that doses of 200 mg/day were tolerable and effective. A total of 28% of all patients had a > 40% decline in PSA, and 18% of patients had a > 50% PSA decline [92]. Another trial combined thalidomide with weekly docetaxel at 30 mg/m2 in patients with metastatic CRPC and compared the results to patients treated with weekly docetaxel alone [93, 94]. The combination was well tolerated except for an increase in thromboembolic events subsequently attributed to thalidomide. Prophylactic anticoagulation drugs have been administered in subsequent trials. Other toxicities included fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, and constipation. There was a greater incidence of PSA declines of > 50% in the combination group (53% compared to 37% in the docetaxel-alone group). Progression-free survival also favored the combination treatment group (5.9 months versus 3.7 months), as did overall survival (25.9 months in the combination group versus 14.7 months in the docetaxel-alone group; P = 0.0407) [95]. Further studies of combination regimens involving thalidomide and thalidomide analogs such as lenalidomide are ongoing.7

Although primarily marketed as an anti-inflammatory agent, selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors have previously been investigated in the treatment of various stages of prostate cancer [96, 97]. Preclinical evidence suggests that COX-2 inhibition has a negative effect on angiogenesis in prostate cancer [98, 99]. The clinical development of COX-2 inhibitors in the treatment of cancer was curtailed after rofecoxib (Vioxx®; Amgen, Thousands Oaks, CA) was implicated in increased cardiovascular morbidity [100]. Further investigation into COX-2 inhibitors suggests that celecoxib (Celebrex®; Pfizer, New York, NY) may have fewer antihypertensive and prothrombotic effects, making it safer than rofecoxib. With appropriate patient selection, celecoxib may be a more viable anticancer therapy [101-103]. A current trial is investigating celecoxib in metastatic CRPC patients in combination with chemotherapy and androgen suppression [104].

A targeted molecular therapy currently in clinical development is ZD4054. This agent was designed to inhibit the endothelin axis, a group of peptides that have been implicated in tumor growth and proliferation [105]. Although it does not directly inhibit angiogenesis, preclinical models suggest that its effects on the endothelin axis decrease new blood vessel formation and serum VEGF levels [106, 107]. After a phase II study suggested a survival benefit in patients with metastatic CRPC after treatment with ZD4054, the agent has entered phase III trials in the same advanced disease state [108, 109].

Docetaxel is another agent with antiangiogenic properties. This drug has important implications for patients with metastatic CRPC. In addition to being the only chemotherapeutic agent to show a survival benefit in prostate cancer, docetaxel is toxic to endothelial cells and may impact angiogenesis in the tumor microenvironment. Notably, when administered in standard doses, docetaxel is cytotoxic to new endothelial cells. In fact, docetaxel has been found to be up to 10 times more effective at inhibiting angiogenesis than paclitaxel [110, 111]. These antiangiogenic characteristics of docetaxel add to the rationale for combining angiogenesis inhibitors with docetaxel in patients with prostate cancer.

COMBINING ANTIANGIOGENESIS INHIBITORS

As targeted monoclonal antibodies and molecular agents have evolved in the last decade, it has become evident that although tumors may respond initially to one agent, tumor cells often develop mechanisms to compensate for the singular point of inhibition in a given pathway. This was observed in a phase II trial of sunitinib in metastatic CRPC, where VEGFR-2 was effectively blocked but increases in the proangiogenesis factor PlGF were found, likely to compensate for the decreased effectiveness of circulating VEGF ligand [76]. In order to circumvent this type of compensatory mechanism, multiple antiangiogenesis inhibitors are being investigated in prostate cancer with the goal of minimizing such tumor escape mechanisms.

A promising phase II study has built upon the standard docetaxel treatment for prostate cancer by adding 2 antiangiogenic agents. In this study, 60 chemotherapy-naïve patients with metastatic CRPC were treated with docetaxel 75 mg/m2 and bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 21 days, in addition to daily thalidomide 200 mg and prednisone 5 mg twice daily. Fifty-eight of 60 patients had PSA declines, with 88% having declines > 50% and 71% having declines > 80%. Among 32 patients with measurable disease, there were 18 partial responses and 2 complete responses. The median estimated progression-free survival was 18.2 months. The treatment was well tolerated, with toxicities including febrile neutropenia (8%), syncope (8%), thrombosis (5%), and fistula/gastrointestinal perforation (5%).8 This study demonstrates promising evidence that multiple antiangiogenic agents can be combined with enhanced clinical benefits. A subsequent trial will investigate docetaxel and prednisone in combination with bevacizumab and lenalidomide.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

With several ongoing trials of angiogenesis inhibitors in metastatic CRPC, the potential role of these targeted therapeutics in prostate cancer continues to evolve. By early 2010, the role of bevacizumab in metastatic CRPC should be clarified. Regardless of the results of that trial, several areas of investigation remain. The potential of angiogenesis inhibitors in early-stage disease will also continue to be evaluated. As new angiogenesis inhibitors come to market, they too may be evaluated alone and in combination with standard therapies. Also, as demonstrated by the bevacizumab/thalidomide/docetaxel combination, there is both scientific and clinical merit for the use of multiple antiangiogenic agents in the treatment of prostate cancer. Almost 4 decades after Dr. Folkman first proposed the role of angiogenesis inhibitors in cancer, cancer patients are reaping the benefits of improved clinical responses. In the years to come, perhaps prostate cancer patients will also benefit from Dr. Folkman’s insight.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Bonnie L. Casey for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Picus, J.; Halabi, S.; Rini, B.; Vogelzang, N.; Whang, Y.; Kaplan, E. The use of bevacizumab with docetaxel and estramustine in hormone refractory prostate cancer: initial results of CALGB 90006 [abstract]. Proc. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol., 2003, 22, 392.

Vuky, J.; Madsen, B.; Hsi, A.; Song, G.; Badiozamani, K.; Warren, S.; Pham, H. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in combination with androgen deprivation and intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in patients with high risk prostate cancer [abstract]. Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, 2008, 145.

Oh, W.; Febbo, P.; Rickie, J.; Fennessy, F.; Scibelli, G.; Hayes, J.; Choueiri, T.; Tempany, C.; Taplin, M.; Ross, R. A phase II study of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with docetaxel and bevacizumab in patients (pts) with high-risk localized prostate cancer: a Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium trial [abstract]. ASCO Meeting Abstracts, 2009, 27, 5060.

Periman, P.; Sonpavde, G.; Bernold, D.; Weckstein, D.; Williams, A.; Zhan, F.; Boehm, K.; Asmar, L.; Hutson, T. Sunitinib malate for metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer following docetaxel-based chemotherapy [abstract]. ASCO Meeting Abstracts, May 20, 2008, 5157.

Karakunnel, J.; Gulley, J.; Arlen, P.; Mulquin, M.; Wright, J.; Turkbey, I.; Choyke, P.; Figg, W.; Dahut, W. Cediranib (AZD2171) in docetaxel-resistant, castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [abstract]. J. Clin. Oncol., 2009, 27(15S), 5141.

Dupont, J.; Camastra, D.; Gordon, M.; Mendelson, D.; Murren, J.; Hsu, A. Phase 1 study of VEGF Trap in patients with solid tumors and lymphoma [abstract]. Proc. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol., 2003, 22, 776.

Moss, R.; Mohile, S.; Shelton, G.; Melia, J.; Petrylak, D. A phase I open-label study using lenalidomide and docetaxel in androgen-independent prostate cancer (AIPC) [abstract]. Prostate Cancer Symposium, 2007, 89.

Ning, Y.; Arlen, P.; Gulley, J.; Stein, W.; Fojo, A.; Latham, L.; Wright, J.; Parnes, J.; Figg, W.; Dahut, W. Phase II trial of thalidomide (T), bevacizumab (Bv), and docetaxel (Doc) in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-refractory prostate cancer (mCRPC) [abstract]. J. Clin. Oncol., 2008, 26(May 20 suppl), 5000.

REFERENCES

- [1].Jemal A; Siegel R; Ward E; Hao Y; Xu J; Thun MJ Cancer statistics, 2009. CA. Cancer J. Clin, 2009, [Epub ahead of print], [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Roehl KA; Han M; Ramos CG; Antenor JA; Catalona WJ Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3,478 consecutive patients: long-term results. J. Urol, 2004, 172(3), 910–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].D'Amico AV; Whittington R; Malkowicz SB; Schultz D; Blank K; Broderick GA; Tomaszewski JE; Renshaw AA; Kaplan I; Beard CJ; Wein A Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA, 1998, 280(11), 969–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zelefsky MJ; Chan H; Hunt M; Yamada Y; Shippy AM; Amols H Long-term outcome of high dose intensity modulated radiation therapy for patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. J. Urol, 2006, 176(4 Pt 1), 1415–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Han M; Partin AW; Zahurak M; Piantadosi S; Epstein JI; Walsh PC Biochemical (prostate specific antigen) recurrence probability following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. J. Urol, 2003, 169(2), 517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sharifi N; Gulley JL; Dahut WL Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. JAMA, 2005, 294(2), 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tannock IF; de Wit R; Berry WR; Horti J; Pluzanska A; Chi KN; Oudard S; Theodore C; James ND; Turesson I; Rosenthal MA; Eisenberger MA Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med, 2004, 351(15), 1502–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Petrylak DP; Tangen CM; Hussain MH; Lara PN Jr.; Jones JA; Taplin ME; Burch PA; Berry D; Moinpour C; Kohli M ; Benson MC; Small EJ; Raghavan D; Crawford ED Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med, 2004, 351(15), 1513–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Folkman J Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N. Engl. J. Med, 1971, 285(21), 1182–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bergers G; Benjamin LE Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 2003, 3(6), 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hanahan D; Folkman J Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell, 1996, 86(3), 353–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dor Y; Porat R; Keshet E Vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular adjustments to perturbations in oxygen homeostasis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol, 2001, 280(6), C1367–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pettersson A; Nagy JA; Brown LF; Sundberg C; Morgan E; Jungles S; Carter R; Krieger JE; Manseau EJ; Harvey VS; Eckelhoefer IA; Feng D; Dvorak AM; Mulligan RC; Dvorak HF Heterogeneity of the angiogenic response induced in different normal adult tissues by vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. Lab. Invest, 2000, 80(1), 99–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hattori K; Heissig B; Wu Y; Dias S; Tejada R; Ferris B; Hicklin DJ; Zhu Z; Bohlen P; Witte L; Hendrikx J; Hackett NR; Crystal RG; Moore MA; Werb Z; Lyden D; Rafii S Placental growth factor reconstitutes hematopoiesis by recruiting VEGFR1(+) stem cells from bone-marrow microenvironment. Nat. Med, 2002, 8(8), 841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Adini A; Kornaga T; Firoozbakht F; Benjamin LE Placental growth factor is a survival factor for tumor endothelial cells and macrophages. Cancer Res., 2002, 62(10), 2749–2752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Holash J; Maisonpierre PC; Compton D; Boland P; Alexan-der CR; Zagzag D; Yancopoulos GD; Wiegand SJ Vessel cooption, regression, and growth in tumors mediated by angiopoietins and VEGF. Science, 1999, 284(5422), 1994–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yancopoulos GD; Davis S; Gale NW; Rudge JS; Wiegand SJ; Holash J Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature, 2000, 407(6801), 242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Benjamin LE; Golijanin D; Itin A; Pode D; Keshet E Selective ablation of immature blood vessels in established human tumors follows vascular endothelial growth factor withdrawal. J. Clin. Invest, 1999, 103(2), 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jain RK; Carmeliet PF Vessels of death or life. Sci. Am, 2001, 285(6), 38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Morikawa S; Baluk P; Kaidoh T; Haskell A; Jain RK; McDonald DM Abnormalities in pericytes on blood vessels and endothelial sprouts in tumors. Am. J. Pathol, 2002, 160(3), 985–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Folberg R; Hendrix MJ; Maniotis AJ Vasculogenic mimicry and tumor angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol, 2000, 156(2), 361–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Epstein RJ VEGF signaling inhibitors: more pro-apoptotic than anti-angiogenic. Cancer Metastasis Rev., 2007, 26(3-4), 443–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhong H; Bowen JP Molecular design and clinical development of VEGFR kinase inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem, 2007, 7(14), 1379–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhao Q; Egashira K; Hiasa K; Ishibashi M; Inoue S; Ohtani K ; Tan C; Shibuya M; Takeshita A; Sunagawa K Essential role of vascular endothelial growth factor and Flt-1 signals in neointimal formation after periadventitial injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, 2004, 24(12), 2284–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gerber HP; Ferrara N Pharmacology and pharmacodynamics of bevacizumab as monotherapy or in combination with cytotoxic therapy in preclinical studies. Cancer Res., 2005, 65(3), 671–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim KJ; Li B; Winer J; Armanini M; Gillett N; Phillips HS; Ferrara N Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factorinduced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivo. Nature, 1993, 362(6423), 841–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Warren RS; Yuan H; Matli MR; Gillett NA; Ferrara N Regulation by vascular endothelial growth factor of human colon cancer tumorigenesis in a mouse model of experimental liver metastasis. J. Clin. Invest, 1995, 95(4), 1789–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pallares J; Rojo F; Iriarte J; Morote J; Armadans LI; de Torres I Study of microvessel density and the expression of the angiogenic factors VEGF, bFGF and the receptors Flt-1 and FLK-1 in benign, premalignant and malignant prostate tissues. Histol. Histopathol, 2006, 21(8), 857–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Weidner N; Carroll PR; Flax J; Blumenfeld W; Folkman J Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastasis in invasive prostate carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol, 1993, 143(2), 401–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].George DJ; Halabi S; Shepard TF; Vogelzang NJ; Hayes DF; Small EJ; Kantoff PW Prognostic significance of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor levels in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer treated on Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9480. Clin. Cancer Res, 2001, 7(7), 1932–1936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bok RA; Halabi S; Fei DT; Rodriquez CR; Hayes DF; Vogelzang NJ; Kantoff P; Shuman MA; Small EJ Vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor urine levels as predictors of outcome in hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Cancer Res., 2001, 61(6), 2533–2536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Concato J; Jain D; Uchio E; Risch H; Li WW; Wells CK Molecular markers and death from prostate cancer. Ann. Intern. Med, 2009, 150(9), 595–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fukumura D; Jain RK Tumor microvasculature and microenvironment: targets for anti-angiogenesis and normalization. Microvasc. Res, 2007, 74(2-3), 72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].O'Reilly MS Radiation combined with antiangiogenic and anti-vascular agents. Semin. Radiat. Oncol, 2006, 16(1), 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhao J; Salmon H; Sarntinoranont M Effect of heterogeneous vasculature on interstitial transport within a solid tumor. Microvasc. Res, 2007, 73(3), 224–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tong RT; Boucher Y; Kozin SV; Winkler F; Hicklin DJ; Jain RK Vascular normalization by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 blockade induces a pressure gradient across the vasculature and improves drug penetration in tumors. Cancer Res, 2004, 64(11), 3731–3736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Winkler F; Kozin SV; Tong RT; Chae SS; Booth MF; Garkavtsev I; Xu L; Hicklin DJ; Fukumura D; di Tomaso E; Munn LL; Jain RK Kinetics of vascular normalization by VEGFR2 blockade governs brain tumor response to radiation: role of oxygenation, angiopoietin-1, and matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Cell, 2004, 6(6), 553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Dickson PV; Hamner JB; Sims TL; Fraga CH; Ng CY; Rajasekeran S; Hagedorn NL; McCarville MB; Stewart CF; Davidoff AM Bevacizumab-induced transient remodeling of the vasculature in neuroblastoma xenografts results in improved delivery and efficacy of systemically administered chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res, 2007, 13(13), 3942–3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tsuzuki Y; Fukumura D; Oosthuyse B; Koike C; Carmeliet P; Jain RK Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) modulation by targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha--> hypoxia response element--> VEGF cascade differentially regulates vascular response and growth rate in tumors. Cancer Res, 2000, 60(22), 6248–6252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Yuan F; Chen Y; Dellian M; Safabakhsh N; Ferrara N; Jain RK Time-dependent vascular regression and permeability changes in established human tumor xenografts induced by an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor antibody. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 1996, 93(25), 14765–14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kim KJ; Li B; Houck K; Winer J; Ferrara N The vascular endothelial growth factor proteins: identification of biologically relevant regions by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Growth Factors, 1992, 7(1), 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Presta LG; Chen H; O'Connor SJ; Chisholm V; Meng YG; Krummen L; Winkler M; Ferrara N Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res., 1997, 57(20), 4593–4599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Margolin K; Gordon MS; Holmgren E; Gaudreault J; Novotny W; Fyfe G; Adelman D; Stalter S; Breed J Phase Ib trial of intravenous recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer: pharmacologic and long-term safety data. J. Clin. Oncol, 2001, 19(3), 851–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Borgstrom P; Hillan KJ; Sriramarao P; Ferrara N Complete inhibition of angiogenesis and growth of microtumors by anti-vascular endothelial growth factor neutralizing antibody: novel concepts of angiostatic therapy from intravital videomicroscopy. Cancer Res., 1996, 56(17), 4032–4039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kabbinavar F; Hurwitz HI; Fehrenbacher L; Meropol NJ; Novotny WF; Lieberman G; Griffing S; Bergsland E Phase II, randomized trial comparing bevacizumab plus fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) with FU/LV alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol, 2003, 21(1), 60–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hurwitz H; Fehrenbacher L; Novotny W; Cartwright T; Hainsworth J; Heim W; Berlin J; Baron A; Griffing S; Holmgren E; Ferrara N; Fyfe G; Rogers B; Ross R; Kabbinavar F Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med, 2004, 555(23), 2335–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Miller K; Wang M; Gralow J; Dickler M; Cobleigh M; Perez EA; Shenkier T; Cella D; Davidson NE Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med, 2007, 357(26), 2666–2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Panares RL; Garcia AA Bevacizumab in the management of solid tumors. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther, 2007, 7(4), 433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].FDA Approves New Combination Therapy for Lung Cancer. 2006. [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2006/ucm108766.htm

- [50].Chustecka Z Bevacizumab Approved for Recurrent Glioblastoma. May 6, 2009. [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/702435

- [51].Reese D; Fratesi P; Corry M; Novotny W; Holmgren E; Small E A phase II trial of humanized anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody for the treatment of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Prostate J., 2001, 3(2), 65. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ryan CJ; Lin AM; Small EJ Angiogenesis inhibition plus chemotherapy for metastatic hormone refractory prostate cancer: history and rationale. Urol. Oncol, 2006, 24(3), 250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Docetaxel and Prednisone With or Without Bevacizumab in Treating Patients With Prostate Cancer That Did Not Respond to Hormone Therapy [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00110214?term=prostate+avastin+docetaxel&rank=3

- [54].Di Lorenzo G; Figg WD; Fossa SD; Mirone V; Autorino R; Longo N; Imbimbo C; Perdona S; Giordano A; Giuliano M; Labianca R; De Placido S Combination of bevacizumab and docetaxel in docetaxel-pretreated hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a phase 2 study. Eur. Urol, 2008, 54(5), 1089–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Rini BI; Weinberg V; Fong L; Conry S; Hershberg RM; Small EJ Combination immunotherapy with prostatic acid phosphatase pulsed antigen-presenting cells (Provenge) plus bevacizumab in patients with serologic progression of prostate cancer after definitive local therapy. Cancer, 2006, 107(1), 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].AUA Late-Breaking Science Forum: Review of the Provenge Trial [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://www.aua2009.org/program/lbsciforum.asp

- [57].Gabrilovich D; Ishida T; Oyama T; Ran S; Kravtsov V; Nadaf S; Carbone DP Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits the development of dendritic cells and dramatically affects the differentiation of multiple hematopoietic lineages in vivo. Blood, 1998, 92(11), 4150–4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gabrilovich DI; Chen HL; Girgis KR; Cunningham HT; Meny GM; Nadaf S; Kavanaugh D; Carbone DP Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat. Med, 1996, 2(10), 1096–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gabrilovich DI; Ishida T; Nadaf S; Ohm JE; Carbone DP Antibodies to vascular endothelial growth factor enhance the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy by improving endogenous dendritic cell function. Clin. Cancer Res, 1999, 5(10), 2963–2970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Jimenez X; Lu D; Brennan L; Persaud K; Liu M; Miao H; Witte L; Zhu Z A recombinant, fully human, bispecific antibody neutralizes the biological activities mediated by both vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 2 and 3. Mol. Cancer Ther, 2005, 4(3), 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Camidge D; Eckhardt S; Diab S; Gore L; Chow L; O’Bryant C; Temmer E; Ervin-Haynes A; Katz T; Fox F; Cohen B A phase I dose-escalation study of weekly IMC-1121B, a fully human anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) IgG1 monoclonal antibody (Mab), in patients (pts) with advanced cancer [abstract]. J. Clin. Oncol, 2006, 24(18S), 3032.16809727 [Google Scholar]

- [62].Study Using IMC-A12 or IMC-1121B Plus Mitoxantrone and Prednisone in Metastatic Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer, Following Disease Progression on Docetaxel-Based Chemotherapy [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00683475?term=IMC-1121B&rank=2cited June 2009

- [63].Kiselyov A; Balakin KV; Tkachenko SE VEGF/VEGFR signalling as a target for inhibiting angiogenesis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs, 2007, 16(1), 83–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Escudier B; Eisen T; Stadler WM; Szczylik C; Oudard S; Siebels M; Negrier S; Chevreau C; Solska E; Desai AA; Rolland F; Demkow T; Hutson TE; Gore M; Freeman S; Schwartz B; Shan M; Simantov R; Bukowski RM Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med, 2007, 556(2), 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Steinbild S; Mross K; Frost A; Morant R; Gillessen S; Dit-trich C; Strumberg D; Hochhaus A; Hanauske AR; Edler L; Burkholder I; Scheulen M A clinical phase II study with sorafenib in patients with progressive hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a study of the CESAR Central European Society for Anticancer Drug Research-EWIV. Br. J. Cancer, 2007, 97(11), 1480–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Safarinejad MR Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in patients with castrate resistant prostate cancer: a phase II study. Urol. Oncol, 2008, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [67].Chi KN; Ellard SL; Hotte SJ; Czaykowski P; Moore M; Ruether JD; Schell AJ; Taylor S; Hansen C; Gauthier I; Walsh W; Seymour L A phase II study of sorafenib in patients with chemo-naive castration-resistant prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol, 2008, 19(4), 746–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Dahut WL; Scripture C; Posadas E; Jain L; Gulley JL; Arlen PM; Wright JJ; Yu Y; Cao L; Steinberg SM; Aragon-Ching JB; Venitz J; Jones E; Chen CC; Figg WD A phase II clinical trial of sorafenib in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res, 2008, 14(1), 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Aragon-Ching JB; Jain L; Gulley JL; Arlen PM; Wright JJ; Steinberg SM; Draper D; Venitz J; Jones E; Chen CC; Figg WD; Dahut WL Final analysis of a phase II trial using sorafenib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. BJU Int., 2009, 155(12), 1636–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Azad NS; Aragon-Ching JB; Dahut WL; Gutierrez M; Figg WD; Jain L; Steinberg SM; Turner ML; Kohn EC; Kong HH Hand-foot skin reaction increases with cumulative sorafenib dose and with combination anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy. Clin. Cancer Res, 2009, 15(4), 1411–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Safety Study of Sorafenib With Androgen Deprivation and Radiotherapy to Treat Prostate Cancer [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00924807?term=sorafenib+prostate+cancer&rank=3

- [72].Sorafenib in Treating Patients Undergoing Radical Prostatectomy for High-Risk Localized Prostate Cancer [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00466752?term=sorafenib+prostate+cancer&rank=5

- [73].Pharmacokinetic Study of BAY43-9006 and Taxotere to Treat Patient With Prostatic Cancer [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00405210?term=sorafenib+prostate+cancer&rank=1

- [74].Motzer RJ; Hutson TE; Tomczak P; Michaelson MD; Bukowski RM; Rixe O; Oudard S; Negrier S; Szczylik C; Kim ST; Chen I; Bycott PW; Baum CM; Figlin RA Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med, 2007, 356(2), 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Mendel DB; Laird AD; Xin X; Louie SG; Christensen JG; Li G; Schreck RE; Abrams TJ; Ngai TJ; Lee LB; Murray LJ; Carver J; Chan E; Moss KG; Haznedar JO; Sukbuntherng J; Blake RA; Sun L; Tang C; Miller T; Shirazian S; McMahon G; Cherrington JM In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin. Cancer Res, 2003, 9(1), 327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Dror Michaelson M; Regan MM; Oh WK; Kaufman DS; Olivier K; Michaelson SZ; Spicer B; Gurski C; Kantoff PW; Smith MR Phase II study of sunitinib in men with advanced prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol, 2009, 20(5), 913–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Clinical Study of SU011248 in Subjects With High Risk Prostate Cancer Who Have Elected to Undergo Radical Prostatectomy [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00790595?term=sunitinib+prostate+cancer&rank=2

- [78].Study Of SU011248 In Combination With Docetaxel (Taxotere) And Prednisone In Patients With Prostate Cancer [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00137436

- [79].Wedge SR; Kendrew J; Hennequin LF; Valentine PJ; Barry ST; Brave SR; Smith NR; James NH; Dukes M; Curwen JO; Chester R; Jackson JA; Boffey SJ; Kilburn LL; Bar-nett S; Richmond GH; Wadsworth PF; Walker M; Bigley AL; Taylor ST; Cooper L; Beck S; Jurgensmeier JM; Ogilvie DJ AZD2171: a highly potent, orally bioavailable, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res, 2005, 65(10), 4389–4400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Drevs J; Siegert P; Medinger M; Mross K; Strecker R; Zirrgiebel U; Harder J; Blum H; Robertson J; Jurgensmeier JM; Puchalski TA; Young H; Saunders O; Unger C Phase I clinical study of AZD2171, an oral vascular endothelial growth factor signaling inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol, 2007, 25(21), 3045–3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ryan CJ; Stadler WM; Roth B; Hutcheon D; Conry S; Puchalski T; Morris C; Small EJ Phase I dose escalation and pharmacokinetic study of AZD2171, an inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in patients with hormone refractory prostate cancer (HRPC). Invest. New Drugs, 2007, 25(5), 445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Liossis SN; Tsokos GC Monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins in medicine. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol, 2005, 116(4), 721–729; quiz 730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Byrne AT; Ross L; Holash J; Nakanishi M; Hu L; Hofmann JI; Yancopoulos GD; Jaffe RB Vascular endothelial growth factor-trap decreases tumor burden, inhibits ascites, and causes dramatic vascular remodeling in an ovarian cancer model. Clin. Cancer Res, 2003, 9(15), 5721–5728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Fukasawa M; Korc M Vascular endothelial growth factor-trap suppresses tumorigenicity of multiple pancreatic cancer cell lines. Clin. Cancer Res, 2004, 10(10), 3327–3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Frischer JS; Huang J; Serur A; Kadenhe-Chiweshe A; McCrudden KW; O’Toole K; Holash J; Yancopoulos GD; Yamashiro DJ; Kandel JJ Effects of potent VEGF blockade on experimental Wilms tumor and its persisting vasculature. Int. J. Oncol, 2004, 25(3), 549–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Aflibercept in Combination With Docetaxel in Metastatic Androgen Independent Prostate Cancer (VENICE) [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00519285?term=Aflibercept+prostate&rank=1

- [87].D'Amato RJ; Loughnan MS; Flynn E; Folkman J Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1994, 91(9), 4082–4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Kenyon BM; Browne F; D'Amato RJ Effects of thalidomide and related metabolites in a mouse corneal model of neovascularization. Exp. Eye Res, 1997, 64(6), 971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Kelsey FO Thalidomide update: regulatory aspects. Teratology, 1988, 38(3), 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Figg WD; Kruger EA; Price DK; Kim S; Dahut WD Inhibition of angiogenesis: treatment options for patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Invest. New Drugs, 2002, 20(2), 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Rajkumar SV; Blood E; Vesole D; Fonseca R; Greipp PR Phase III clinical trial of thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a clinical trial coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol, 2006, 24(3), 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Figg WD; Dahut W; Duray P; Hamilton M; Tompkins A; Steinberg SM; Jones E; Premkumar A; Linehan WM; Floeter MK; Chen CC; Dixon S; Kohler DR; Kruger EA; Gubish E; Pluda JM; Reed E A randomized phase II trial of thalidomide, an angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res, 2001, 7(7), 1888–1893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Figg WD; Arlen P; Gulley J; Fernandez P; Noone M; Fedenko K; Hamilton M; Parker C; Kruger EA; Pluda J; Dahut WL A randomized phase II trial of docetaxel (Taxotere) plus thalidomide in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Semin. Oncol, 2001, 28(4 Suppl 15), 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Dahut WL; Gulley JL; Arlen PM; Liu Y; Fedenko KM; Steinberg SM; Wright JJ; Parnes H; Chen CC; Jones E; Parker CE; Linehan WM; Figg WD Randomized phase II trial of docetaxel plus thalidomide in androgen-independent prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol, 2004, 22(13), 2532–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Figg W; Retter A; Steinberg S; Dahut W In reply. J. Clin. Oncol, 2005, 23(9), 2113–2114.15774812 [Google Scholar]

- [96].Smith MR; Manola J; Kaufman DS; Oh WK; Bubley GJ; Kantoff PW Celecoxib versus placebo for men with prostate cancer and a rising serum prostate-specific antigen after radical prostatectomy and/or radiation therapy. J. Clin. Oncol, 2006, 24(18), 2723–2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Pruthi RS; Derksen JE; Moore D; Carson CC; Grigson G; Watkins C; Wallen E Phase II trial of celecoxib in prostate-specific antigen recurrent prostate cancer after definitive radiation therapy or radical prostatectomy. Clin. Cancer Res, 2006, 12(7 Pt 1), 2172–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Liu XH; Kirschenbaum A; Yao S; Lee R; Holland JF; Levine AC Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 suppresses angiogenesis and the growth of prostate cancer in vivo. J. Urol, 2000, 164(3 Pt 1), 820–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Masferrer JL; Leahy KM; Koki AT; Zweifel BS; Settle SL; Woerner BM; Edwards DA; Flickinger AG; Moore RJ; Seibert K Antiangiogenic and antitumor activities of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Cancer Res, 2000, 60(5), 1306–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Bresalier RS; Sandler RS; Quan H; Bolognese JA; Oxenius B; Horgan K; Lines C; Riddell R; Morton D; Lanas A; Konstam MA; Baron JA Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N. Engl. J. Med, 2005, 352(11), 1092–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Madan RA; Xia Q; Chang VT; Oriscello RG; Kasimis B A retrospective analysis of cardiovascular morbidity in metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients on high doses of the selective COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib. Expert Opin. Pharmacother, 2007, 8(10), 1425–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Solomon DH; Schneeweiss S; Levin R; Avorn J Relationship between COX-2 specific inhibitors and hypertension. Hypertension, 2004, 44(2), 140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].White WB; Faich G; Borer JS; Makuch RW Cardiovascular thrombotic events in arthritis trials of the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib. Am. J. Cardiol, 2003, 92(4), 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Androgen Suppression Alone or Combined With Zoledronate, Docetaxel, Prednisolone, and/or Celecoxib in Treating Patients With Locally Advanced or Metastatic Prostate Cancer [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00268476?term=celecoxib+prostate&rank=6

- [105].Goldie RG Endothelins in health and disease: an overview. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol, 1999, 26(2), 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Salani D; Di Castro V; Nicotra MR; Rosano L; Tecce R; Venuti A; Natali PG; Bagnato A Role of endothelin-1 in neovascularization of ovarian carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol, 2000, 157(5), 1537–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Rosano L; Di Castro V; Spinella F; Tortora G; Nicotra MR; Natali PG; Bagnato A Combined targeting of endothelin A receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor in ovarian cancer shows enhanced antitumor activity. Cancer Res, 2007, 57(13), 6351–6359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].James ND; Caty A; Borre M; Zonnenberg BA; Beuzeboc P; Morris T; Phung D; Dawson NA Safety and efficacy of the specific endothelin-A receptor antagonist ZD4054 in patients with hormone-resistant prostate cancer and bone metastases who were pain free or mildly symptomatic: a double-blind, placebocontrolled, randomised, phase 2 trial. Eur. Urol, 2008, [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [109].A Phase III Trial of ZD4054 (Endothelin A Antagonist) in Hormone Resistant Prostate Cancer With Bone Metastases (ENTHUSE M1) [cited June 2009]; Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00554229?term=zd4054+prostate+cancer&rank=1

- [110].Hotchkiss KA; Ashton AW; Mahmood R; Russell RG; Sparano JA; Schwartz EL Inhibition of endothelial cell function in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo by docetaxel (Taxotere): association with impaired repositioning of the microtubule organizing center. Mol. Cancer Ther, 2002, 1(13), 1191–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Grant DS; Williams TL; Zahaczewsky M; Dicker AP Com-parison of antiangiogenic activities using paclitaxel (Taxol) and docetaxel (Taxotere). Int. J. Cancer, 2003, 104(1), 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]