Abstract

The dexamethasone-suppressed CRH test (Dex-CRH test) differentiates patients with Cushing syndrome (CS) from those with pseudo-Cushing states (PCS), who have decreased ACTH responses to CRH because of negative feedback exerted by chronic hypercortisolism. Normal subjects, however, have not been studied with the Dex-CRH test, raising concern that this test might not separate patients with CS from patients with normal adrenal function. To determine whether the criterion that separates CS from PCS would also differentiate patients with Cushing disease (CD) from individuals with eucortisolism, we studied 20 healthy volunteers, during low-dose (2 mg/d) dexamethasone suppression, and then during the Dex-CRH test (CRH stimulation test performed 2 hours after completion of low-dose dexamethasone suppression), and contrasted their results with those of 20 patients with surgically proven mild CD (urine free cortisol <1000 nmol/d).

Basal urine free cortisol was significantly greater in patients with CD (p < 0.001), but within the normal range (55–250 nmol/d) in 4 patients. During low-dose dexamethasone suppression, a urine free cortisol < 100 nmol/d (36 μg/d) was found in all but one volunteer subject, and a urine 17-hydroxycorticosteroid excretion < 14.6 μmol/d (5.3 mg/d), was found in all but two subjects. During the Dex-CRH test, plasma cortisol < 38 nmol/L was found in all 20 normal volunteers, until 30 minutes following CRH administration. By contrast, the 15-minute CRH-stimulated plasma cortisol exceeded 38 nmol/L in all patients with CD (p < 0.001). Plasma dexamethasone measured just prior to CRH administration was similar in normal volunteers (13.0 ± 6.1 μmol/L) and patients with CD (16.4 ± 6.4 μmol/L). We conclude that cortisol measurements obtained during the Dex-CRH test are suppressed in normal volunteers below those found in mild CD. These results suggest that while the Dex-CRH test may be useful in the evaluation of CS in patients without significant hypercortisoluria, its value in patients with episodic hormonogenesis has not been tested.

Keywords: glucocorticoid, hypercortisolism, hyperadrenalism, differential diagnosis, cortisol, ACTH, 17-hydroxycorticosteroid, urine free cortisol

Introduction

Several tests are currently in clinical use to differentiate Cushing syndrome (CS) from conditions causing pseudo-Cushing states (PCS), such as depression, stress, renal failure, alcoholism or obesity. The low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (1–3) measures 17-hydroxycorticosteroid excretion during administration of dexamethasone, 0.5 mg every six hours for two days. When 17-hydroxycorticosteroid excretion exceeds 11.0 μmol/d (4 mg/d) (4), the test is considered positive for CS. However, this test may misclassify as many as 15% of patients with CS and up to 15% of patients with PCS (5). The corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation test, valuable in differentiating the syndrome of ectopic ACTH from Cushing disease (6, 17), is also of limited use in the differential diagnosis between PCS and Cushing disease (CD) because there is considerable overlap with the responses of patients with CD (5, 7–9). Other tests to distinguish CD from PCS have been described, but not fully tested (4, 10).

The lack of a test with both high sensitivity and high specificity for CS led to the development of the dexamethasone-suppressed CRH (Dex-CRH) test. In a pilot study, 39 patients with CS and 19 patients believed to have PCS were given dexamethasone 0.5 mg q 6h for 8 doses, followed by administration of 1 μg/kg ovine CRH 2h after the last dose of dexamethasone. In this study, a plasma cortisol value measured 15 minutes after CRH administration that was greater than 38 nmol/L had 100% diagnostic accuracy for CS, and the Dex-CRH test had superior sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy when compared either to the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test or to the CRH test performed alone (5).

Patients with PCS have decreased ability to secrete ACTH in response to CRH because of the glucocorticoid negative feedback exerted by chronic hypercortisolism (11). However, many patients referred for endocrinologic evaluation to rule out CS either have no evidence for hypercortisoluria, or minimal elevation of urine free cortisol (UFC) or 17-hydroxycorticosteroids (17OHCS). Because such individuals have not been exposed to chronic hypercortisolism, they might have a greater ACTH and cortisol response to the Dex-CRH test than those with a sustained PCS. To determine whether the criterion that separates CS from PCSs will also distinguish CS from individuals without hypercortisolism, we compared the results of the Dex-CRH test in 20 normal volunteers and in 20 patients with CD.

Methods

Subjects

Twenty volunteers (ages 22–58 y), 10 males and 10 females, were recruited through posted notices in the Bethesda, MD area (Table 1). Twenty patients with surgically-proven CD were referred to NIH for evaluation of mild hypercortisolism (UFC < 1000 nmol/d, normal range 50–250 nmol/d) between May 1992 and February 1994, and have not been the subjects of any prior report. These 20 patients underwent biochemical tests to determine the cause of their CS (12, 15, 17, 25). Based on results of testing, they underwent transsphenoidal pituitary exploration, which revealed an adenoma with ACTH staining in each case. All normal volunteers were medication-free for at least two weeks before the start of study, and all were free of significant medical disease. None of the normal volunteers had evidence of any psychiatric disorder known to affect the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis, and all had refrained from the use of any steroid preparation for a minimum of three months prior to study. The study was approved by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Clinical Research Subpanel and each subject gave written consent for participation.

Table 1:

Study Patients.

| Healthy Volunteers (n=20) | Cushing Disease (n=20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 32.6 ± 9.8 | 37.5 ± 10.9 |

| Body mass Index (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 3.6 | 35.3 ± 14.5* |

| Gender | 10 female | 16 female |

| Race | 19 Caucasian, 1 Hispanic | 18 Caucasian, 1 Hispanic, 1 Pacific Islander |

| Basal 24 h urine free cortisol excretion, nmol/d (normal 50–250 nmol/d) | 103 ± 73 | 493 ± 252* |

| Basal 17-hydroxycorticosteroid excretion, μmol/d (normal 5.5–22.0 nmol/d) | 15.8 ± 7.3 | 46.9 ± 17.7* |

Mean ± standard deviation.

p < 0.001 Cushing disease vs healthy volunteers.

Study Protocol

In all subjects, the 24-hour excretion of UFC, 17OHCS, and creatinine was measured for one day while subjects took no glucocorticoids, and subsequently during administration of 0.5 mg dexamethasone orally every 6 hours for 8 doses, starting at 12:00 noon.

A dexamethasone-suppressed CRH test was performed in all subjects, starting two hours after the patient had completed dexamethasone treatment. Ovine CRH (Bachem, Torrance, Calif) was administered as an intravenous bolus injection at a dose of 1 μg/kg between 0800 and 0810. Plasma samples were assayed for cortisol and ACTH at −15, −10, −5, and −1 min before CRH stimulation, and then at 5, 15, 30, 45 and 60 minutes after CRH, and for dexamethasone at -1 min. Normal volunteers underwent CRH testing in the endocrine outpatient clinic. Patients with CD were admitted to the inpatient endocrinology ward of the Warren Grant Magnuson NIH Clinical Center for testing.

Hormone Assays

UFC, 17OHCS, and creatinine were measured as previously described (12). The intraassay and interassay variabilities were 8 – 12 % and 8 – 15% for UFC, 6 −12% and 7–20% for 17OHCS, and 1% and 2% for creatinine. Daily creatinine measurements varied by no more than 10%. Plasma ACTH and cortisol were measured as previously described (6) by Corning Hazleton Laboratories (Vienna, VA). The sensitivity for the ACTH assay ranged from 0.9 to 2.2 pmol/L and for cortisol from 5.5 to 22 nmol/L. The intraassay and interassay variabilities were 7 to 12 % and 12 to 25 % for ACTH, and 6 and 15 % for cortisol. Each cortisol sample was also measured in a second, serum cortisol assay, performed by the Clinical Pathology Laboratory of the NIH Clinical Center, using the Abbott TDX kit. Results were equivalent, except that Abbott kit cortisol determinations had a higher limit of detection (27.6 nmol/L) than those measured at Corning Hazleton Laboratories (5.5–22 nmol/L). In this report, results from the Corning Hazleton Laboratories plasma cortisol assay are given. Plasma samples were assayed for dexamethasone by Endocrine Sciences (Calabasas Hills, CA). The intraassay and interassay variability for the plasma dexamethasone assay were 3.4 % and 8.4 %, respectively.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed on a Macintosh Power PC using SuperAnova and StatView 4.5 (Abacus Concepts, Inc., Berkeley, CA), and RuleMaker (Digital, Hanover, MA). After logarithmic data transformation, analysis of variance with repeated measures was performed for plasma cortisol and plasma ACTH measurements, employing a conservative (Greenhouse-Geisser) F test. The relation between dexamethasone level and plasma cortisol was determined by simple regression. After dexamethasone administration, UFC and 17OHCSwere not normally distributed, and were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Tabular data are presented as mean ± SD.

Estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and diagnostic accuracy were determined for each test statistic (13). The sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy of each of the test criteria were compared at 100% specificity by chi-square statistics (14). We compared the criteria for the diagnosis of CD of the various tests using cut-points with 100% specificity for the diagnosis of CS from PCS found in our previous retrospective study (5).

Results

Low-Dose Dexamethasone Suppression

Urine 17-hydroxycorticosteroid and free cortisol were measured before and during dexamethasone administration in all subjects. Both urine 17-hydroxycorticosteroid and free cortisol excretion were significantly greater in patients with CD (Table 1, p <0.001). UFC was within the normal range (55–250 nmol/d) in 4 of the 20 patients with CD (none with episodic hypersecretion of cortisol), and greater than the normal range in one normal volunteer (290 nmol/L).

Both UFC and 17-OHCS decreased significantly following dexamethasone administration in both groups (Table 2, Table 3, p < 0.001). During the second day of dexamethasone suppression, one normal volunteer had a UFC greater than 100 nmol/d (36 μg/d), and two normal volunteers had urine 17-hydroxycorticosteroid excretion > 14.6 μmol/d (5.3 mg/d). These values represented cut-points with 100% specificity for the diagnosis of CS in our previous retrospective study (5). Using lower values of urinary 17-HOHCS or UFC as the cut points for the diagnosis of CD yielded similar results: A 17-hydroxycorticosteroid > 6.9 μmol/day (2.5 mg/day) for the diagnosis of CD had 90% sensitivity and 65% specificity. A UFC criterion > 56 nmol/day (20 μg/day) had 75% sensitivity and 93% specificity for the diagnosis of CD.

Table 2:

Results Following Dexamethasone Suppression

| Healthy Volunteers (n=20) | Cushing Disease (n=20) | |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma dexamethasone, μmol/L | 13.0 ± 6.1 | 16.4 ± 6.4 |

| Dexamethasone-suppressed urine free cortisol excretion, nmol/d | 16.0 ± 20.1Π | 168.3 ± 144Π* |

| Dexamethasone-suppressed 17-hydroxycorticosteroid excretion, μmol/d | 6.9 ± 4.5Π | 16.9 ± 9.1Π* |

| Dexamethasone-suppressed basal plasma cortisol, nmol/L | 27.1 ± 3.6 | 152 ± 185* |

| Dexamethasone-suppressed plasma Cortisol 15 min after CRH, nmol/L | 27.4 ± 4.0 | 256 ± 195* |

Mean ± standard deviation.

p < 0.001 Cushing disease vs healthy volunteers.

p < 0.001 vs measurement before administration of dexamethasone.

Table 3:

Comparison of tests

| Test Variable | Criterion | Specificity | Sensitivity | + Pred. Value | − Pred. Value | Diagnostic Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEX-CRH test cortisol 15’ after CRH | >38.6 nmol/L | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Dex-CRH test basal cortisol | >38.6 nmol/L | 1.00 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.90 |

| Dex-CRH test peak cortisol | >44.2 nmol/L | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

| Dex-CRH test ACTH 30’ after CRH | >3.5 pmol/L | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

| Dex-CRH test peak ACTH | >3.5 pmol/L | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Basal 17-OHCS | >34.5 μmol/d | 1.00 | 0.55∇ | 1.00 | 0.69∇ | 0.78∇ |

| Basal UFC | >290 nmol/d | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.87 |

| Low-dose dex 17-OHCS | > 17.9 μmol/d | 1.00 | 0.60∇ | 1.00 | 0.71∇ | 0.80∇ |

| Low-dose dex UFC | > 128.8 nmol/d | 1.00 | 0.50∇ | 1.00 | 0.67∇ | 0.75∇ |

Table 3: Comparison of criteria with 100% specificity for the diagnosis of Cushing disease.

p < 0.05, vs Dex-CRH test 15-minute cortisol. UFC, urine free cortisol excretion; 17-OHCS, urine 17-hydroxycorticosteroid excretion.

CRH Test With Dexamethasone Pretreatment (Dex-CRH test)

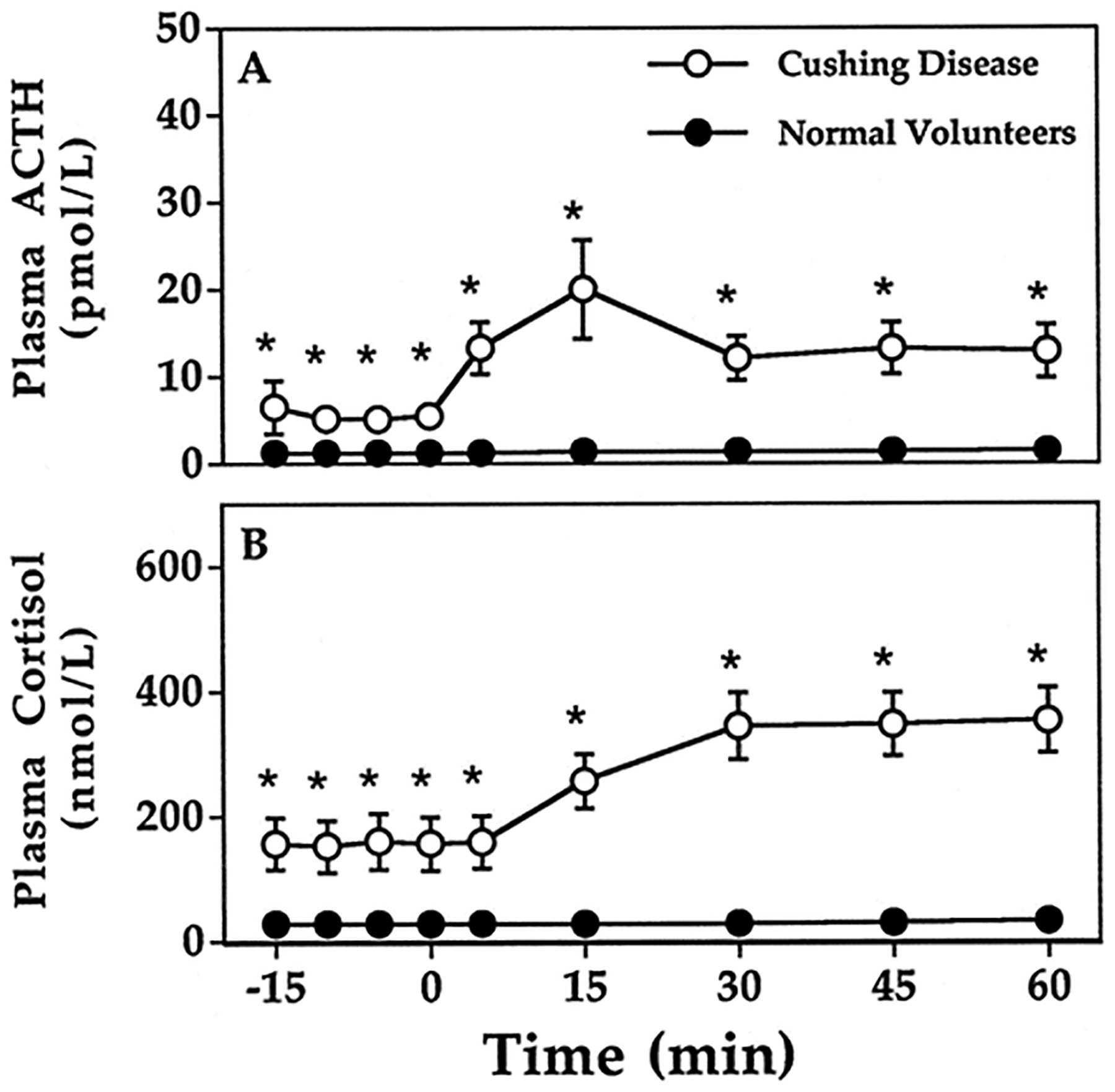

All subjects completed the Dex-CRH test (Figure 1, Tables 2 and 3). ANOVA showed significant group-by-time interactions (p < 0.001). Plasma ACTH increased significantly in both groups (basal ACTH 6.47 ± 3.0 and peak ACTH 25.2 ± 27.1 pmol/L, p < 0.001 for CD; basal ACTH 1.19 ± 0.05 and peak ACTH 1.56 ± 0.14 pmol/L, p < 0.04 for normal volunteers). Plasma cortisol rose significantly in patients with CD (basal cortisol 156.14 ± 41.64, peak cortisol 471.58 ± 67.02 nmol/L, p < 0.001), but did not change significantly in normal volunteers (basal cortisol 27.29 ± 0.83, peak cortisol 31.92 ± 2.57 nmol/L, p = 0.07). Both plasma ACTH and cortisol were significantly greater in patients with CD at all time points (p <0.001).

Figure 1:

Results of CRH stimulation testing with low-dose dexamethasone pretreatment. Plasma ACTH in patients with Cushing Disease (A) and in normal volunteers (C). Plasma cortisol in patients with Cushing Disease (B) and in normal volunteers (D). Means and standard errors of measurement are shown when SEM is greater than size of data point.  , Cushing disease;

, Cushing disease;  , healthy volunteers. *p < 0.001, Cushing disease vs. healthy volunteers. Note differing y-axis scaling for Cushing Disease and for normal volunteers that is required to show each data point.

, healthy volunteers. *p < 0.001, Cushing disease vs. healthy volunteers. Note differing y-axis scaling for Cushing Disease and for normal volunteers that is required to show each data point.

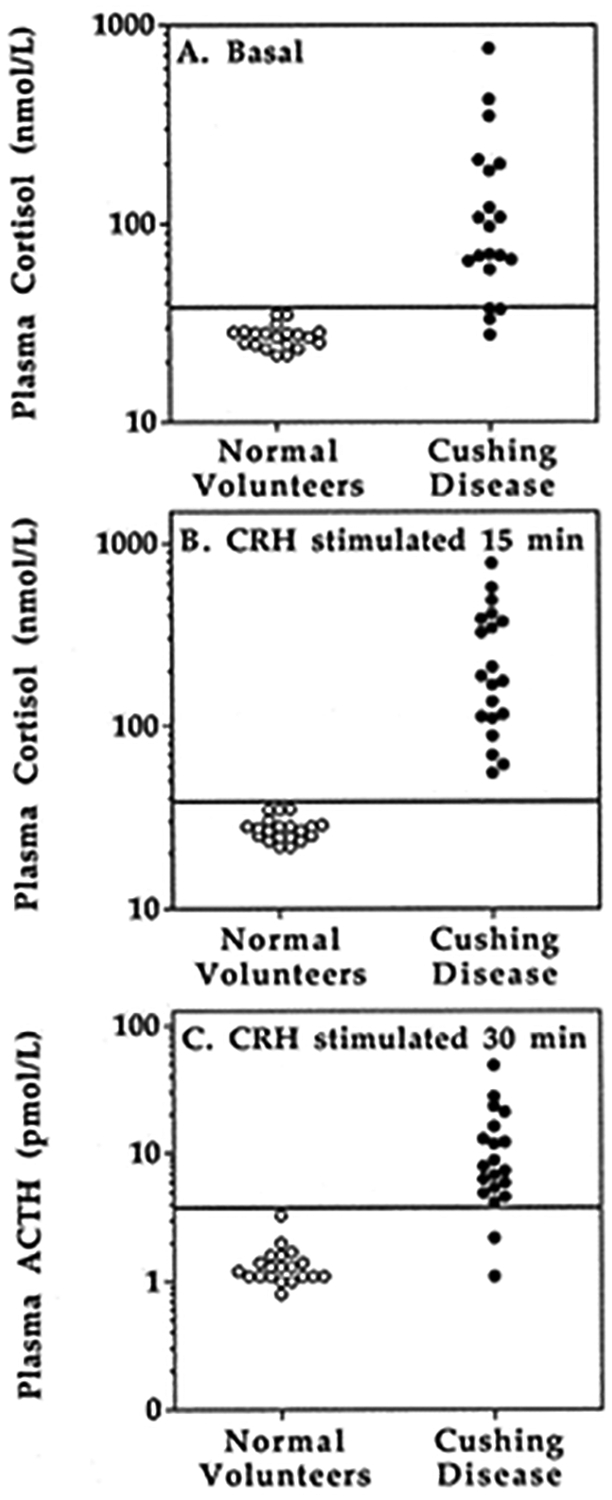

As was previously observed in individuals with PCS, a Dex-CRH test plasma cortisol concentration < 38 nmol/L was found in all 20 normal volunteers, both basally and at all times between 0 and 30 minutes following administration of CRH (Fig 1). The plasma cortisol of two normal volunteers exceeded 38 nmol/L at 45 and 60 minutes following CRH. A plasma cortisol < 38 nmol/L was found before administration of CRH in four patients with CD (Fig 2A), but in all cases, a cortisol concentration in excess of 38 nmol/L was found 15 minutes after CRH stimulation (Fig 2B). The criterion for dexamethasone-suppressed plasma ACTH that was best for distinguishing CD was a plasma ACTH > 3.5 pmol/L at 30 minutes (Fig 2C), which had 100% specificity and 90% sensitivity for the diagnosis of CD. Results using peak ACTH or peak cortisol response did not have 100% diagnostic accuracy.

Figure 2:

Individual data showing the criteria with the best diagnostic accuracy. A: Basal plasma cortisol after dexamethasone-suppression. B: Dex-CRH plasma cortisol obtained 15 minutes after CRH stimulation. C. Dex-CRH plasma ACTH obtained 30 minutes after CRH stimulation.  , Cushing disease;

, Cushing disease;  , healthy volunteers.

, healthy volunteers.

The mean plasma dexamethasone level (Table 2) measured just prior to CRH administration did not differ for normal volunteers (13.0 ± 6.1 μmol/L; 469.5 ± 220.4 ng/dL) and patients with CD (16.4 ± 6.4 μmol/L; 614.8 ± 233.1 ng/dL). The two normal volunteers whose plasma cortisol exceeded 38 nmol/L at 45 and 60 minutes following CRH had the two lowest plasma dexamethasone values (6.90 and 4.03 μmol/L). In patients with CD, dexamethasone levels and plasma ACTH or cortisol measurements were not correlated, either at basal or CRH-stimulated time points (p = 0.41, data not shown).

Comparison of tests

When compared at criteria yielding 100% specificity for the diagnosis of CD, the Dex-CRH test 15-minute cortisol concentration had significantly greater sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy than dexamethasone suppressed urine 17-hydroxycorticosteroid or free cortisol measurements (Table 3). While basal plasma cortisol after dexamethasone administration did not correctly identify 4 patients with CD, this 80% sensitivity, when compared to the 100% sensitivity of the CRH-stimulated plasma cortisol level, was not statistically significant (p = 0.3). Similar results were found using peak CRH-stimulated ACTH, ACTH 30 minutes after CRH stimulation, or peak CRH-stimulated cortisol values (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, the Dex-CRH test, a new test for the differential diagnosis of hypercortisolism, distinguished all patients with mild CD from healthy volunteers using criteria previously established to discriminate pseudo-Cushing states from CD. The Dex-CRH-stimulated cortisol value obtained 15 minutes after administration of CRH had better diagnostic accuracy for the diagnosis of CD than either basal 24h urine 17-hydroxycorticosteroid measurements, or dexamethasone-suppressed urine measurements. Although the 15 min Dex-CRH test did not have significantly greater diagnostic accuracy than basal UFC (p = 0.06), basal dexamethasone-suppressed plasma cortisol (p = 0.3), peak dexamethasone-suppressed plasma cortisol (p = 0.6), or Dex-CRH plasma ACTH (p = 0.6), the Dex-CRH test 15-minute cortisol criterion was the only evaluated criterion with both 100% specificity and sensitivity. While the overnight 1 mg dexamethasone suppression test would likely eliminate at least 90% of normocortisoluric individuals from consideration of the diagnosis of CS, the overnight 1 mg dexamethasone suppression test is of lesser value in differentiating individuals with PCS and CS (4). Since we wished to evaluate a test that could differentiate patients with CS from all individuals without the disorder, we did not perform the 1 mg test in the subjects of the present study.

Most patients with CD show some suppression of adrenocorticotropin and cortisol by dexamethasone (6, 8, 12, 15, 16), and some stimulation of adrenocorticotropin and cortisol by CRH (6, 17). However, cortisol secretion decreases greatly in some patients with CD during low-dose dexamethasone, possibly because of slow dexamethasone clearance (18, 19). Such patients may be misclassified as having PCS if evaluated only by suppression of cortisol production after low-dose dexamethasone administration. In the present study, 4 subjects with CD had dexamethasone-suppressed basal plasma cortisol values < 38 nmol/L. By the addition of CRH to stimulate greater adrenocorticotropin and cortisol secretion in patients with CD who are CRH-sensitive, those patients with unusual sensitivity to dexamethasone suppression achieve greater adrenocorticotropin and cortisol levels, above those of patients with PCS (5) or normal volunteers. In this manner, the Dex-CRH test correctly identifies more patients with CD than does low-dose dexamethasone suppression, and therefore allows the criterion for the diagnosis of CS to be 100% specific with a much higher sensitivity than is possible with dexamethasone suppression alone.

Four of the patients with CD in this study had basal UFC excretion that was within the normal range. All four of these patients had Dex-CRH-stimulated cortisol levels greater than the 38 nmol/L cut point identified in our previous study (5), and were correctly identified by the Dex-CRH test. In contrast, healthy volunteers showed suppression of plasma ACTH and cortisol similar to that observed previously for patients with PCS (5). These results lead us to believe that the Dex-CRH test may be of value for determining who has true CS among patients with normal, or only mildly elevated, UFC measurements. However, the value of the Dex-CRH test in classifying those who have CS with periodic hormonogenesis (20–24), but who are not hypercortisolemic at the time of testing, remains unknown.

The observation that the lowest plasma dexamethasone levels in the study were found in the two normal volunteers whose Dex-CRH-stimulated plasma cortisol increased above 38 nmol/L at 45 min, suggests that dexamethasone levels may aid interpretation of the Dex-CRH test. As with other tests using dexamethasone, the Dex-CRH test should be interpreted with caution in patients receiving medications that affect dexamethasone metabolism.

We conclude that plasma cortisol measurements obtained during the Dex-CRH test are suppressed in normal volunteers below those found in CD. Although its value in patients with episodic hormonogenesis has not been demonstrated, the Dex-CRH test may be useful in evaluating patients with features of CS and little, or no, hypercortisoluria.

Acknowledgments

We thank the nurses of the 10-West Endocrinology inpatient ward and 9-ACRF outpatient clinic at the National Institutes of Health, Barbara Filmore, and Shawnia Forrester for helping to carry out this study.

References

- 1.Liddle G. 1960. Tests of pituitary-adrenal suppressibility in the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 20:1539–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eddy R, Jones A, Gilliland PF, et al. 1973. Cushing’s Syndrome: a prospective study of diagnostic methods. Am J Med. 55:621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schteingart D. 1989. Cushing’s Syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 18:311–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crapo LM. 1979. Cushing’s syndrome: a review of diagnostic tests. Metab. 28:955–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanovski JA, Cutler GB Jr., Chrousos GP, Nieman LK. 1993. Corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulation following low-dose dexamethasone administration: A new test to distinguish Cushing’s syndrome from pseudo-Cushing’s states. J Am Med Assoc. 269:2232–2238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieman LK, Chrousos GP, Oldfield EH, Avgerinos PC, Cutler G Jr., Loriaux DL. 1986. The ovine corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test and the dexamethasone suppression test in the differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 105:862–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold PW, Loriaux DL, Roy A, et al. 1986. Physiology of hypercortisolism in depression and Cushing’s disease. N Engl J Med. 314:1329–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossman A, Howlett T, Perry L, et al. 1988. CRF in the differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: A comparison with the dexamethasone suppression test. Clin Endocrinol. 29:167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rupprecht R, Lesch K, Muller U, et al. 1989. Blunted adrenocorticotropin but normal ß-endorphin release after human corticotropin-releasing hormone administration in depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 69:600–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernini GP, Argenio GF, Cerri F, Franchi F. 1994. Comparison between the suppressive effects of dexamethasone and loperamide on cortisol and ACTH secretion in some pathological conditions. J Endocrinol Invest. 17:799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yanovski JA. 1995. The Dexamethasone-suppressed CRH test in the differential diagnosis of Cushing disease and pseudo-Cushing states. The Endocrinologist. 5:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avgerinos PC, Yanovski JA, Oldfield EH, Nieman LK, Cutler G Jr. 1994. The metyrapone and dexamethasone suppression tests for the differential diagnosis of the adrenocorticotropin-dependent Cushing syndrome: a comparison. Ann Intern Med. 121:318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swets JA. 1988. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 240:1285–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck JR, Shultz EK. 1986. The use of relative operating characteristic (ROC) curves in test performance evaluation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 110:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flack MR, Oldfield EH, Cutler GB Jr, et al. 1992. Urine free cortisol in the high-dose dexamethasone suppression test for the differential diagnosis of the Cushing syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 116:211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dichek HL, Nieman LK, Oldfield EH, Pass HI, Malley JD, Cutler G Jr. 1994. A comparison of the standard high dose dexamethasone suppression test and the overnight 8-mg dexamethasone suppression test for the differential diagnosis of adrenocorticotropin-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 78:418–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nieman LK, Oldfield EH, Wesley R, Chrousos GP, Loriaux DL, Cutler G Jr. 1993. A simplified morning ovine corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulation test for the differential diagnosis of adrenocorticotropin-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 77:1308–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caro JF, Meikle AW, Check JH, Cohen SN. 1978. “Normal Suppression” to dexamethasone in Cushing’s disease: An expression of decreased metabolic clearance for dexamethasone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 47:667–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapcala LP, Hamilton SM, Meikle AW. 1984. Cushing’s disease with ‘normal suppression’ due to decreased dexamethasone clearance. Arch Intern Med. 144:636–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown RD, Van Loon GR, Orth DN, Liddle GW. 1973. Cushing’s disease with periodic hormonogenesis: one explanation for paradoxical response to dexamethasone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 36:445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasuda K. 1996. Cyclic Cushing’s disease: pitfalls in the diagnosis and problems with the pathogenesis. Intern Med. 35:169–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermus AR, Pieters GF, Borm GF, et al. 1993. Unpredictable hypersecretion of cortisol in Cushing’s disease: detection by daily salivary cortisol measurements. Acta Endocrinol. 128:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart PM, Venn P, Heath DA, Holder G. 1992. Cyclical Cushing’s syndrome. Br J Hosp Med. 48:186–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro MS, Shenkman L. 1991. Variable hormonogenesis in Cushing’s syndrome. Q J Med. 79:351–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Findling JW, Doppman JL. Biochemical and Radiologic diagnosis of Cushing syndrome. Endocr. Metab Clin North Am 23(3):511–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]