Abstract

Objective

Previous studies regarding cigarette smoking causing a lower risk of melanoma are inconclusive. Here, we re-examined melanoma risk in relation to cigarette smoking in a large, case-control study.

Methods

In total 1,157 patients with melanoma diagnosed between 2003 and 2011 in the Netherlands and 5,595 controls from the Nijmegen Biomedical Study were included. Information concerning smoking habits and known risk factors for melanoma were obtained through self-administered questionnaires. Logistic regression analyses stratified by gender were performed to study the risk of cigarette smoking on melanoma risk, adjusted for age, marital status, highest level of education, skin type, sun vacation, use of solarium, time spent outdoors, and sun protective measures.

Results

Among men, current and former smokers did not have a higher risk of melanoma compared to never smokers: adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 0.56 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.40–0.79) and adjusted OR = 0.50 (95% CI: 0.39–0.64), respectively. With an increasing number of years smoked the risk of melanoma decreased: <20 years: OR = 0.61 (95% CI: 0.46–0.80); 21–40 years: OR = 0.50 (95% CI: 0.37–0.68); >40 years: OR = 0.26 (95% CI: 0.15–0.44). No clear trend was found for the number of cigarettes smoked. Results for females were less clear and not statistically significant (current smoker: adjusted OR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.74–1.26, former smoker: adjusted OR = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.73–1.08).

Conclusion

This study shows a strong inverse association between cigarette smoking and melanoma risk in men. Fundamental laboratory research is necessary to investigate the biological relation between smoking cigarettes and melanoma.

Keywords: Cigarette smoking, Melanoma, Risk factors, Case-control study

Introduction

Cutaneous melanoma has been the most rapidly increasing malignancy over the last 50 years, particularly in countries with a predominantly fair-skinned population [1]. At the same time, the survival rate has greatly improved. This is mainly due to the early detection of melanoma [2, 3, 4]. The most important known risk factors for the development of melanoma are genetic predisposition, skin type, and intermittent exposure to UV radiation [5, 6].

Tobacco smoke is a known risk factor for several types of cancers [7]. Cigarette smoking is also known to come with an increased risk of premature skin aging, psoriasis, poor wound healing, and squamous cell carcinoma [8]. Previous studies have explored the effect of smoking on the risk of cutaneous melanoma, but evidence is inconsistent [9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. Seven of these studies, which are mainly prospective cohort studies, reported an inverse relationship between current smoking and melanoma [9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 19]. It is suggested that the nicotine in cigarette smoke protects the skin from the inflammatory reaction induced by UV radiation and therefore reduces melanoma risk [25, 26]. Also, a different lifestyle of smokers versus nonsmokers might be associated with a reduced melanoma risk in cigarette smokers, as smokers are suggested to spend more time indoors [27].

The other nine studies did not find a significant association between cigarette smoking and melanoma [10, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 28]. Possible explanations for these results are the small sample size in several of these studies and residual confounding.

In the current study we investigated the association between cigarette smoking and primary melanoma risk in a large case-control study in the Netherlands.

Materials and Methods

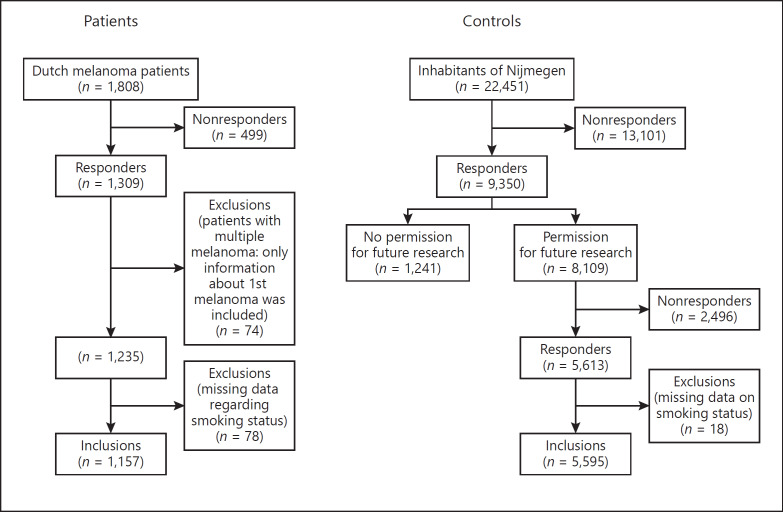

For further details, see the online supplementary material (see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000502129 for all online suppl. material) [29] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of Materials and Methods.

Results

The patient and lifestyle characteristics of patients and controls are presented in Table 1 for males and Table 2 for females, based on observed data as well as imputed data. Male and female patients were slightly older than controls, were more often living together with a partner, had a lower level of education, had more often a skin type I or II, more frequent sunburns, and more usage of solarium and sun protective measures. Therefore, the multivariable analyses were adjusted for age, marital status, skin type, highest level of education, time spent outdoors, sun vacations, use of solarium, and sun protective measures.

Table 1.

Patient and lifestyle characteristics of male patients and controls

| Males | Patients (n = 440) | Patients (after imputation) | Controls (n = 2,548) | Controls (after imputation) | OR (95% CI)1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at completion of questionnaire, years | 57.5±12.5 | 55.2±16.5 | 1.00 (1.00–1.02) | ||

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 155 (35.2) | 652 (25.6) | reference | ||

| Current | 57 (13.0) | 424 (16.6) | 0.57 (0.41–0.78) | ||

| Former | 228 (51.8) | 1,472 (57.8) | 0.65 (0.52–0.82) | ||

| Duration of smoking2 | |||||

| Never smoker | 155 (35.2) | 652 (25.6) | reference | ||

| <20 years | 119 (27.0) | 692 (27.2) | 0.72 (0.56–0.94) | ||

| 21–40 years | 94 (21.4) | 596 (23.4) | 0.66 (0.50–0.88) | ||

| >40 years | 20 (4.5) | 227 (8.9) | 0.37 (0.23–0.61) | ||

| Cigarettes per day | |||||

| Never smoker | 155 (35.2) | 652 (25.6) | reference | ||

| <10 | 106 (24.1) | 755 (29.6) | 0.59 (0.45–0.77) | ||

| 10–20 | 109 (24.8) | 696 (27.3) | 0.66 (0.50–0.86) | ||

| >20 | 28 (6.4) | 206 (8.1) | 0.57 (0.37–0.88) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 45 (10.3) | 46 (10.5) | 535 (21.0) | 535 (21.0) | reference |

| With partner | 391 (88.9) | 394 (89.5) | 2,008 (79.0) | 2,013 (79.0) | 2.30 (1.67–3.18) |

| Missing | 4 (1.0) | 5 (0.2) | |||

| Education | |||||

| Less than secondary school | 101 (23.0) | 102 (23.2) | 565 (22.2) | 568 (22.3) | reference |

| Secondary school | 146 (33.2) | 146 (33.2) | 677 (26.6) | 680 (26.7) | 1.21 (0.93–1.56) |

| More than secondary school | 192 (43.6) | 192 (43.6) | 1,294 (50.8) | 1,300 (51.0) | 1.46 (1.16–1.85) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 12 (0.5) | |||

| Skin type | |||||

| I, II | 203 (46.1) | 203 (46.1) | 912 (35.8) | 914 (35.9) | reference |

| III | 231 (52.5) | 231 (52.5) | 1,481 (58.1) | 1,484 (58.2) | 0.70 (0.57–0.86) |

| IV–VI | 6 (1.3) | 6 (1.3) | 146 (5.7) | 150 (5.9) | 0.18 (0.08–0.41) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 9 (0.4) | |||

| Skin reaction after 1 h unprotective sun exposure | |||||

| Not burned | 46 (10.5) | 46 (10.5) | 574 (22.5) | 577 (22.6) | reference |

| A little bit red | 254 (57.7) | 254 (57.7) | 1,523 (59.8) | 1,531 (60.1) | 2.08 (1.50–2.89) |

| Burned | 140 (31.8) | 140 (31.8) | 437 (17.2) | 440 (17.3) | 4.00 (2.80–5.71) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 14 (0.5) | |||

| Solarium usage during lifetime | |||||

| Never | 201 (45.7) | 202 (45.9) | 1,440 (56.5) | 1,457 (57.2) | reference |

| <2 cycles | 195 (44.3) | 196 (44.5) | 795 (31.2) | 799 (31.4) | 1.76 (1.42–2.18) |

| 2–5 cycles | 36 (8.2) | 36 (8.2) | 215 (8.4) | 216 (8.5) | 1.21 (0.82–1.78) |

| >5 cycles | 6 (1.4) | 6 (1.4) | 71 (2.8) | 76 (3.0) | 0.61 (0.26–1.44) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 27 (1.1) | |||

| Time spent outdoors weekdays <18 years (hours per day) | |||||

| <2 h | 253 (57.5) | 256 (58.2) | 1,437 (56.4) | 1,472 (57.8) | reference |

| 2–4 h | 113 (25.7) | 117 (26.6) | 700 (27.5) | 721 (28.3) | 0.91 (0.72–1.16) |

| >4 h | 65 (14.8) | 67 (15.2) | 324 (12.7) | 355 (13.9) | 1.09 (0.81–1.46) |

| Unknown | 9 (2.0) | 87 (3.4) | |||

| Time spent outdoors weekends/holidays <18 years (hours per day) | |||||

| <2 h | 48 (10.9) | 48 (10.9) | 249 (9.8) | 258 (10.1) | reference |

| 2–4 h | 303 (68.9) | 307 (69.8) | 1,783 (70.0) | 1,856 (72.8) | 0.88 (0.63–1.23) |

| >4 h | 79 (18.0) | 85 (19.3) | 385 (15.1) | 434 (17.0) | 1.04 (0.71–1.54) |

| Unknown | 10 (2.3) | 131 (5.1) | |||

| Time spent outdoors weekdays >18 years (hours per day) | |||||

| <2 h | 286 (65.0) | 289 (65.7) | 1,673 (65.7) | 1,699 (66.7) | reference |

| 2–4 h | 109 (24.8) | 111 (25.2) | 595 (23.4) | 606 (23.8) | 1.07 (0.84–1.36) |

| >4 h | 38 (8.6) | 40 (9.1) | 233 (9.1) | 243 (9.5) | 0.97 (0.68–1.38) |

| Unknown | 7 (1.6) | 47 (1.8) | |||

| Time spent outdoors weekends/holidays >18 years (hours per day) | |||||

| <2 h | 88 (20.0) | 89 (20.2) | 570 (22.4) | 590 (23.2) | reference |

| 2–4 h | 295 (67.0) | 301 (68.4) | 1,578 (61.9) | 1,663 (65.3) | 1.20 (0.93–1.55) |

| >4 h | 46 (10.5) | 50 (11.4) | 255 (10.0) | 295 (11.6) | 1.09 (0.75–1.60) |

| Unknown | 11 (2.5) | 145 (5.7) | |||

| Sun vacation <18 years (weeks per year) | |||||

| None | 251 (57.0) | 251 (57.0) | 1,467 (57.6) | 1,510 (59.3) | reference |

| 1–2 weeks | 110 (25.0) | 110 (25.0) | 547 (21.5) | 567 (22.3) | 1.17 (0.92–1.50) |

| 3–4 weeks | 65 (14.8) | 65 (14.8) | 407 (16.0) | 429 (16.8) | 0.91 (0.68–1.21) |

| >4 weeks | 14 (3.2) | 14 (3.2) | 39 (1.5) | 42 (1.6) | 1.90 (1.00–3.62) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 88 (3.5) | |||

| Sun vacation >18 years (weeks per year) | |||||

| None | 87 (19.8) | 87 (19.8) | 568 (22.3) | 607 (23.8) | reference |

| 1–2 weeks | 180 (40.9) | 180 (40.9) | 923 (36.2) | 957 (37.6) | 1.30 (0.98–1.72) |

| 3–4 weeks | 164 (37.3) | 164 (37.3) | 882 (34.6) | 929 (36.5) | 1.23 (0.93–1.63) |

| >4 weeks | 9 (2.0) | 9 (2.0) | 53 (2.1) | 55 (2.2) | 1.12 (0.53–2.36) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 122 (4.8) | |||

| Sun protective measures <18 years | |||||

| Never | 38 (8.6) | 41 (9.3) | 229 (9.0) | 302 (11.9) | reference |

| Rarely/sometimes | 273 (62.0) | 295 (67.0) | 1,441 (56.6) | 1,742 (68.4) | 1.24 (0.81–1.91) |

| Often/always | 92 (20.9) | 104 (23.6) | 419 (16.4) | 504 (19.8) | 1.47 (0.90–2.39) |

| Missing | 37 (8.4) | 459 (18.0) | |||

| Sun protective measures >18 years | |||||

| Never | 12 (2.7) | 15 (3.4) | 93 (3.6) | 123 (4.8) | reference |

| Rarely/sometimes | 186 (42.3) | 200 (45.5) | 1,216 (47.7) | 1,418 (55.7) | 1.26 (0.64–2.48) |

| Often/always | 213 (48.4) | 225 (51.1) | 891 (35.0) | 1,007 (39.5) | 1.95 (1.00–3.82) |

| Missing | 29 (6.6) | 348 (13.6) | |||

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

The imputed data were used for analyses.

Data of patients and controls who smoke or had smoked and did not specify their smoking behavior in duration of smoking or number of cigarettes per day were not imputed.

Table 2.

Patient and lifestyle characteristics of female patients and controls

| Females | Patients (n = 717) | Patients (after imputation) | Controls (n = 3,047) | Controls (after imputation) | OR (95% CI)1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at completion of questionnaire, years | 52.9±13.2 | 50.2±17.1 | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | ||

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 319 (44.5) | 1,341 (44.0) | reference | ||

| Current | 111 (15.5) | 480 (15.8) | 0.97 (0.77–1.24) | ||

| Former | 287 (40.0) | 1,226 (40.2) | 0.98 (0.82–1.12) | ||

| Duration of smoking2 | |||||

| Never smoker | 319 (44.5) | 1,341 (44.0) | reference | ||

| <20 years | 219 (30.5) | 770 (25.3) | 1.20 (0.99–1.45) | ||

| 21–40 years | 112 (15.6) | 475 (15.6) | 0.99 (0.78–1.26) | ||

| >40 years | 24 (3.3) | 142 (4.7) | 0.71 (0.45–1.11) | ||

| Cigarettes per dayNever smoker | 319 (44.5) | 1,341 (44.0) | reference | ||

| <10 | 245 (34.2) | 887 (29.1) | 1.16 (0.96–1.40) | ||

| 10–20 | 107 (14.9) | 514 (16.9) | 0.88 (0.69–1.11) | ||

| >20 | 25 (3.5) | 126 (4.1) | 0.83 (0.53–1.30) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 137 (19.1) | 139 (19.4) | 1,079 (35.4) | 1,084 (35.6) | reference |

| With partner | 575 (80.2) | 578 (80.6) | 1,959 (64.3) | 1,963 (64.4) | 2.28 (1.86–2.79) |

| Missing | 5 (0.7) | 9 (0.3) | |||

| Education | |||||

| Less than secondary school | 172 (24.0) | 172 (24.0) | 646 (21.2) | 650 (21.3) | reference |

| Secondary school | 260 (36.3) | 260 (36.3) | 880 (28.9) | 883 (29.0) | 1.11 (0.89–1.38) |

| More than secondary school | 285 (39.7) | 285 (39.7) | 1,507 (49.5) | 1,514 (49.7) | 0.71 (0.58–0.88) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 14 (0.5) | |||

| Skin type | |||||

| I, II | 378 (52.7) | 378 (52.7) | 1,386 (45.5) | 1,394 (45.7) | reference |

| III | 331 (46.2) | 331 (46.2) | 1,522 (50.0) | 1,526 (50.1) | 0.80 (0.68–0.94) |

| IV–VI | 8 (1.1) | 8 (1.1) | 125 (4.1) | 127 (4.2) | 0.24 (0.11–0.48) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 14 (0.5) | |||

| Skin reaction after 1 h unprotective sun exposure | |||||

| Not burned | 66 (9.2) | 66 (9.2) | 582 (19.1) | 585 (19.2) | reference |

| A little bit red | 398 (55.5) | 398 (55.5) | 1,801 (59.1) | 1,810 (59.4) | 1.95 (1.48–2.57) |

| Burned | 253 (35.3) | 253 (35.3) | 646 (21.2) | 652 (21.4) | 3.46 (2.58–4.64) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 18 (0.6) | |||

| Solarium usage during lifetime | |||||

| Never | 168 (23.4) | 169 (23.6) | 1,015 (33.3) | 1,034 (33.9) | reference |

| <2 cures | 403 (56.2) | 403 (56.2) | 1,176 (38.6) | 1,190 (39.1) | 2.07 (1.70–2.53) |

| 2–5 cures | 126 (17.6) | 126 (17.6) | 614 (20.2) | 620 (20.3) | 1.24 (0.97–1.60) |

| >5 cures | 19 (2.7) | 19 (2.6) | 201 (61.2) | 203 (6.7) | 0.58 (0.35–0.95) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 41 (1.3) | |||

| Time spent outdoors weekends/holidays <18 years (hours per day) | |||||

| <2 h | 96 (13.4) | 97 (13.5) | 460 (15.1) | 479 (15.7) | reference |

| 2–4 h | 420 (58.6) | 434 (60.5) | 1,801 (59.1) | 1,874 (61.5) | 1.13 (0.88–1.44) |

| >4 h | 182 (25.4) | 186 (25.9) | 633 (20.8) | 694 (22.8) | 1.31 (0.99–1.72) |

| Unknown | 19 (2.6) | 153 (5.0) | |||

| Time spent outdoors weekdays >18 years (hours per day) | |||||

| <2 h | 494 (68.9) | 498 (69.5) | 2,146 (70.4) | 2,209 (72.5) | reference |

| 2–4 h | 133 (18.5) | 133 (18.5) | 499 (16.4) | 520 (17.1) | 1.16 (0.93–1.44) |

| >4 h | 82 (11.4) | 86 (12.0) | 304 (10.0) | 318 (10.4) | 1.17 (0.90–1.52) |

| Unknown | 8 (1.1) | 98 (3.2) | |||

| Time spent outdoors weekends/holidays >18 years (hours per day) | |||||

| <2 h | 162 (22.6) | 168 (23.4) | 697 (22.9) | 727 (23.9) | reference |

| 2–4 h | 438 (61.1) | 451 (62.9) | 1,863 (61.1) | 1,934 (63.5) | 1.00 (0.82–1.22) |

| >4 h | 91 (12.7) | 98 (13.7) | 345 (11.3) | 386 (12.7) | 1.06 (0.80–1.41) |

| Unknown | 26 (3.6) | 142 (4.7) | |||

| Sun vacation <18 years (weeks per year) | |||||

| None | 378 (52.7) | 378 (52.7) | 1,705 (56.0) | 1,744 (57.2) | reference |

| 1–2 weeks | 192 (26.8) | 192 (26.8) | 740 (24.3) | 761 (25.0) | 1.17 (0.96–1.42) |

| 3–4 weeks | 121 (16.9) | 121 (16.9) | 500 (16.4) | 518 (17.0) | 1.08 (0.86–1.36) |

| >4 weeks | 26 (3.6) | 26 (3.6) | 21 (0.7) | 24 (0.8) | 4.62 (2.43–8.78) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 81 (2.7) | |||

| Sun vacation >18 years (weeks per year) | |||||

| None | 123 (17.2) | 123 (17.2) | 584 (19.2) | 606 (19.9) | reference |

| 1–2 weeks | 341 (47.6) | 341 (47.6) | 1,271 (41.7) | 1,327 (43.6) | 1.28 (1.02–1.60) |

| 3–4 weeks | 215 (30.0) | 215 (30.0) | 1,017 (33.4) | 1,062 (34.9) | 1.00 (0.78–1.28) |

| >4 weeks | 38 (5.3) | 38 (5.3) | 51 (1.7) | 52 (1.7) | 3.37 (2.08–5.48) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 124 (4.1) | |||

| Sun protective measures <18 years | |||||

| Never | 36 (5.0) | 40 (5.6) | 138 (4.5) | 198 (6.5) | reference |

| Rarely/sometimes | 389 (54.3)) | 438 (61.1) | 1,436 (47.1) | 1,730 (56.8) | 1.23 (0.82–1.85) |

| Often/always | 204 (28.5) | 239 (33.3) | 897 (29.4) | 1,119 (36.7 | 1.10 (0.74–1.63) |

| Missing | 88 (12.3) | 576 (18.9) | |||

| Sun protective measures >18 years | |||||

| Never | 6 (0.8) | 7 (1.0) | 35 (1.1) | 62 (2.0) | reference |

| Rarely/sometimes | 239 (33.3) | 260 (36.3) | 1,112 (36.5) | 1,317 (43.2) | 1.66 (0.58–4.77) |

| Often/always | 432 (60.3) | 450 (62.8) | 1,446 (47.5) | 1,668 (54.7) | 2.34 (0.77–7.12) |

| Missing | 40 (5.6) | 454 (14.9) | |||

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

The imputed data were used for analyses.

Data of patients and controls who smoke or had smoked and did not specify their smoking behavior in duration of smoking or number of cigarettes per day were not imputed.

The adjusted ORs of melanoma associated with cigarette smoking for males and females are presented in Table 3. Both current and former male smokers did not have a higher risk of melanoma compared to never smokers. Current smokers had an adjusted OR of 0.56 (95% CI: 0.40–0.79) and former smokers had an adjusted OR of 0.50 (95% CI: 0.39–0.64). In addition, with an increasing number of years smoked the risk of melanoma decreased: <20 years: OR = 0.61 (95% CI: 0.46–0.80); 21–40 years: OR = 0.50 (95% CI: 0.37–0.68); >40 years: OR = 0.26 (95% CI: 0.15–0.44). No clear trend was found for the number of cigarettes smoked. All results in females were less clear. Current smokers had an adjusted OR of 0.96 (95% CI: 0.74–1.26) compared to never smokers, whereas former smokers had an adjusted OR of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.73–1.08).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios of melanoma associated with cigarette smoking

| Adjusted OR1 (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|

| males | females | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | reference | reference |

| Current | 0.56 (0.40–0.79) | 0.96 (0.74–1.26) |

| Former | 0.50 (0.39–0.64) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) |

| Duration of smoking | ||

| Never smoker | reference | reference |

| <20 years | 0.61 (0.46–0.80) | 1.18 (0.95–1.46) |

| 21–40 years | 0.50 (0.37–0.68) | 0.90 (0.70–1.17) |

| >40 years | 0.26 (0.15–0.44) | 0.55 (0.34–0.89) |

| Cigarettes per day | ||

| Never smoker | reference | reference |

| <10 | 0.50 (0.37–0.67) | 1.11 (0.90–1.36) |

| 10–20 | 0.52 (0.39–0.70) | 0.79 (0.61–1.02) |

| >20 | 0.44 (0.28–0.69) | 0.80 (0.49–1.29) |

OR adjusted for age, marital status, skin type, highest level of education, time spent outdoors, sun vacations, use of solarium, and sun protective measures.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between cigarette smoking and risk of developing a primary melanoma. From the results it can be concluded that cigarette smoking does not increase the risk of melanoma. Among males, cigarette smoking might even decrease the risk of melanoma. In addition, the melanoma risk appeared to decrease with a longer duration of cigarette smoking. No clear trend was found with increasing number of cigarettes smoked per day. In females, the results of all analyses were less clear and not statistically significant.

These results for both males and females are largely in accordance with several previous studies [9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17]. However, none of the previous studies found an inverse association between cigarette smoking and melanoma risk as strong as that observed among males in our study. Also, studies have been published without an inverse association between cigarette smoking and risk of melanoma [10, 14, 16, 18, 22, 28]. Possible explanations for these conflicting observations might be a smaller number of subjects, another time frame with different smoking behavior, and the lack of melanoma-associated confounders (number of nevi, number of atypical nevi, and genetic predisposition). Also, possibly fewer studies with an inverse association between cigarette smoking and melanoma are published because of ethical issues regarding the possible harmful effect on health care.

Several possible explanations for the observed inverse relation between cigarette smoking and the risk of melanoma have been suggested. A low socioeconomic status is linked to higher smoking prevalence [30] and people of lower socioeconomic status have less exposure to specific lifestyle factors associated with melanoma risk, such as recreational UV exposure and tanning, which may decrease melanoma incidence [31]. Also, smokers presumably spend more time indoors and therefore have less UV exposure [27]. In addition, because of an overall healthier lifestyle it is likely that never smokers have more medical surveillance and earlier detection of disease compared with smokers. Therefore, smokers might have fewer full body skin examinations by a physician compared to never smokers, which results in a delayed detection of melanoma. In our study, we adjusted all risk estimates for the level of education as approximation for socioeconomic status and for the time people spend outdoors. However, we cannot fully exclude the possible effect of other factors associated with cigarette smoking (residual confounding).

It is hypothesized that smoking may protect melanocytes from the inflammatory reaction induced by long-term UV radiation [25, 26]. This effect of smoking may be partially caused by the long-term effect of nicotine. Cigarette smoke contains many reactive oxygen species, but also UV irradiation causes the production of reactive oxygen species, which are responsible for induction of proinflammatory cytokines. The anti-inflammatory effects of nicotine are mediated by α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which are also located on cells of the immune system, like macrophages [32]. They inhibit the release of proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-6, and IL-8) via the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and promote the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines.

In addition, nicotine causes vasoconstriction of peripheral blood vessels including those of the skin, possibly by reduced prostacyclin production [33, 34], which affects the inflammatory response in the skin.

Recently, it has been discovered that genetic predisposition exists for smoking behavior [35, 36]. In a subsequent study an inverse association between smoking behavior-related genetic variants in the chromosome 15q25.1 region and risk of melanoma, especially in males, was observed [37]. This suggests that smoking behavior-related single nucleotide polymorphisms play a role in melanoma development and might indicate that smoking is indeed causally related to melanoma risk.

The inverse association between cigarette smoking and melanoma was most prominently seen in males. These results are consistent with results reported by previous studies [9, 12, 15, 17]. A recent twin study with intravenous infusions of nicotine and cotinine (the most important metabolite of nicotine) showed that nicotine and cotinine metabolism is higher in women compared to men. In addition, use of an oral contraceptive further accelerates nicotine and cotinine metabolism [38, 39]. The gender difference was also detected in recent studies among smokers, showing that the ratio of the nicotine metabolite trans-3′-hydroxycotinine to cotinine in blood or urine is significantly higher in women, supporting the abovementioned faster metabolism in women compared to men [40, 41]. These changes in metabolism seem to be due to hormonal differences. Also, evidence exists that the activity of a member of the cytochrome p450 proteins (CYP) superfamily of enzymes, the CYP2A6 enzyme, is induced by sex hormones and there is recent in vitro evidence for the induction of human CYP2A6 by estrogen acting on the estrogen receptor [42]. Women are suggested to have more active CYP enzyme activity and therefore metabolize more nicotine which reduces the anti-inflammatory effect of nicotine in relation to melanoma development, which means that the melanoma-protecting effect in women is less pronounced [43]. These gender differences in metabolism could explain the observed strong inverse association between cigarette smoking and melanoma risk in men compared to the lesser effect observed in women.

The main strengths of this population-based study include its large number of subjects and the extensive collection of exposure information with the ability to adjust for the most important confounders. Our questionnaire information represents the best possible approach regarding sun behavior by using different variables as a proxy for intermittent and cumulative sun exposure. A previous study showed that self-reported information on melanoma risk factors is fairly well reproducible and is useful in research settings [44].

There are also limitations. Information on smoking behavior and confounding factors was retrieved after the diagnosis of melanoma. Therefore, recall bias cannot be excluded. However, we have no reason to believe that patients and controls answer questions regarding smoking habits differently, because the public's awareness of the association between cigarette smoking and melanoma is probably very low. Patients might have answered the questions regarding sun behavior in a different way compared to controls because of their higher awareness of melanoma risk factors. Unfortunately, for this study we were not able to include information concerning the presence of atypical nevi, number of nevi, and genetic predisposition, which are important risk factors for melanoma [45]. Also, the cohort time periods are not concomitant across the two cohorts of patients and controls, which may cause a risk of bias. Societal attitudes towards lifestyle and smoking habits might have changed and could therefore influence response behavior because of social desirability. Furthermore, with a response rate of 42% in the control population, a selection bias might be introduced. The response rate for the questionnaire was slightly higher for older age categories than for younger age categories [29]. However, compared to our patients, there is no great difference in mean age. Among patients who had smoked, there is some missing data regarding the number of years of cigarette smoking and number of cigarettes per day, which could introduce bias. However, lack of this information is not dependent on the extent of smoking. Systematic bias is therefore not to be expected, but the observed effect might be less strong.

In conclusion, we observed that cigarette smoking does not increase the risk of developing a primary melanoma. Male smokers might have a decreased risk of melanoma. In females the results were less pronounced. Given the limitations of this study and possible residual confounding no direct clinical impact can be reduced from these results. Encouraging smoking cessation remains of utmost importance. However, if one of the components of tobacco smoke causes a protective effect on the development of melanoma, this might be of meaning for high-risk patients in the future. To investigate a (causal) biological mechanism underlying the association between smoking cigarettes and melanoma risk and to identify which component(s) of cigarette smoke might be protective, fundamental laboratory studies are necessary.

Key Message

Cigarette smoking does not increase melanoma risk.

Statement of Ethics

All patients and controls gave written informed consent. The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the registration team of the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL) for the collection of data for the Netherlands Cancer Registry.

The Nijmegen Biomedical Study is a population-based survey conducted at the Department for Health Evidence and the Department of Laboratory Medicine of the Radboud University Medical Center. Principal investigators of the Nijmegen Biomedical Study are L.A.L.M. Kiemeney, A.L.M. Verbeek, D.W. Swinkels, and B. Franke.

References

- 1.Forman D. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Volume X. IACR; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crocetti E, Mallone S, Robsahm TE, Gavin A, Agius D, Ardanaz E, et al. EUROCARE-5 Working Group Survival of patients with skin melanoma in Europe increases further: results of the EUROCARE-5 study. Eur J Cancer. 2015 Oct;51((15)):2179–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erdmann F, Lortet-Tieulent J, Schüz J, Zeeb H, Greinert R, Breitbart EW, et al. International trends in the incidence of malignant melanoma 1953-2008—are recent generations at higher or lower risk? Int J Cancer. 2013 Jan;132((2)):385–400. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bay C, Kejs AM, Storm HH, Engholm G. Incidence and survival in patients with cutaneous melanoma by morphology, anatomical site and TNM stage: a Danish Population-based Register Study 1989-2011. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015 Feb;39((1)):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu S, Han J, Laden F, Qureshi AA. Long-term ultraviolet flux, other potential risk factors, and skin cancer risk: a cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014 Jun;23((6)):1080–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, Pasquini P, Zanetti R, Masini C, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: III. Family history, actinic damage and phenotypic factors. Eur J Cancer. 2005 Sep;41((14)):2040–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, et al. WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group A review of human carcinogens—Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Nov;10((11)):1033–4. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freiman A, Bird G, Metelitsa AI, Barankin B, Lauzon GJ. Cutaneous effects of smoking. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004 Nov-Dec;8((6)):415–23. doi: 10.1007/s10227-005-0020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blakely T, Barendregt JJ, Foster RH, Hill S, Atkinson J, Sarfati D, et al. The association of active smoking with multiple cancers: national census-cancer registry cohorts with quantitative bias analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2013 Jun;24((6)):1243–55. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wensveen CA, Bastiaens MT, Kielich CJ, Berkhout MJ, Westendorp RG, Vermeer BJ, et al. Leiden Skin Cancer Study Relation between smoking and skin cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Jan;19((1)):231–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLancey JO, Hannan LM, Gapstur SM, Thun MJ. Cigarette smoking and the risk of incident and fatal melanoma in a large prospective cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 2011 Jun;22((6)):937–42. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9766-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedman DM, Sigurdson A, Doody MM, Rao RS, Linet MS. Risk of melanoma in relation to smoking, alcohol intake, and other factors in a large occupational cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2003 Nov;14((9)):847–57. doi: 10.1023/b:caco.0000003839.56954.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson M.T., Kubo JT, Desai M, David SP, Tindle H, Sinha AA, et al. Smoking behavior and association of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer in the Women's Health Initiative. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Jan;72((1)):190–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessides MC, Wheless L, Hoffman-Bolton J, Clipp S, Alani RM, Alberg AJ. Cigarette smoking and malignant melanoma: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Jan;64((1)):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odenbro A, Gillgren P, Bellocco R, Boffetta P, Håkansson N, Adami J. The risk for cutaneous malignant melanoma, melanoma in situ and intraocular malignant melanoma in relation to tobacco use and body mass index. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Jan;156((1)):99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osterlind A, Tucker MA, Stone BJ, Jensen OM. The Danish case-control study of cutaneous malignant melanoma. IV. No association with nutritional factors, alcohol, smoking or hair dyes. Int J Cancer. 1988 Dec;42((6)):825–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910420604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song F, Qureshi AA, Gao X, Li T, Han J. Smoking and risk of skin cancer: a prospective analysis and a meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012 Dec;41((6)):1694–705. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westerdahl J, Olsson H, Måsbäck A, Ingvar C, Jonsson N. Risk of malignant melanoma in relation to drug intake, alcohol, smoking and hormonal factors. Br J Cancer. 1996 May;73((9)):1126–31. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z, Wang Z, Yu Y, Zhang H, Chen L. Smoking is inversely related to cutaneous malignant melanoma: results of a meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Dec;173((6)):1540–3. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millen AE, Tucker MA, Hartge P, Halpern A, Elder DE, Guerry D, 4th, et al. Diet and melanoma in a case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004 Jun;13((6)):1042–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Marchand L, Saltzman BS, Hankin JH, Wilkens LR, Franke AA, Morris SJ, et al. Sun exposure, diet, and melanoma in Hawaii Caucasians. Am J Epidemiol. 2006 Aug;164((3)):232–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gogas H, Trakatelli M, Dessypris N, Terzidis A, Katsambas A, Chrousos GP, et al. Melanoma risk in association with serum leptin levels and lifestyle parameters: a case-control study. Ann Oncol. 2008 Feb;19((2)):384–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batty GD, Kivimaki M, Gray L, Smith GD, Marmot MG, Shipley MJ. Cigarette smoking and site-specific cancer mortality: testing uncertain associations using extended follow-up of the original Whitehall study. Ann Oncol. 2008 May;19((5)):996–1002. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Melchi F, Pilla MA, Antonelli G, Camaioni D, et al. A protective effect of the Mediterranean diet for cutaneous melanoma. Int J Epidemiol. 2008 Oct;37((5)):1018–29. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishisgori C. Current concept of photocarcinogenesis. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2015 Sep;14((9)):1713–21. doi: 10.1039/c5pp00185d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sopori M. Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002 May;2((5)):372–7. doi: 10.1038/nri803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santmyire BR, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB., Jr Lifestyle high-risk behaviors and demographics may predict the level of participation in sun-protection behaviors and skin cancer primary prevention in the United States: results of the 1998 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2001 Sep;92((5)):1315–24. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1315::aid-cncr1453>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones MS, Jones PC, Stern SL, Elashoff D, Hoon DS, Thompson J, et al. The Impact of Smoking on Sentinel Node Metastasis of Primary Cutaneous Melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017 Aug;24((8)):2089–94. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5775-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galesloot TE, Vermeulen SH, Swinkels DW, de Vegt F, Franke B, den Heijer M, et al. Cohort Profile: The Nijmegen Biomedical Study (NBS) Int J Epidemiol. 2017 Aug;46((4)):1099–1100j. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casetta B, Videla AJ, Bardach A, Morello P, Soto N, Lee K, et al. Association between cigarette smoking prevalence and income level: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016:ntw266. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang AJ, Rambhatla PV, Eide MJ. Socioeconomic and lifestyle factors and melanoma: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Apr;172((4)):885–915. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ingram JR. Nicotine: does it have a role in the treatment of skin disease? Postgrad Med J. 2009 Apr;85((1002)):196–201. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.073577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mills CM, Hill SA, Marks R. Altered inflammatory responses in smokers. BMJ. 1993 Oct;307((6909)):911. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6909.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moszczyński P, Zabiński Z, Moszczyński P, Jr, Rutowski J, Słowiński S, Tabarowski Z. Immunological findings in cigarette smokers. Toxicol Lett. 2001 Jan;118((3)):121–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(00)00270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen LS, Hung RJ, Baker T, Horton A, Culverhouse R, Saccone N, et al. CHRNA5 risk variant predicts delayed smoking cessation and earlier lung cancer diagnosis—a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015 Apr;107((5)):djv100. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor AE, Morris RW, Fluharty ME, Bjorngaard JH, Åsvold BO, Gabrielsen ME, et al. Stratification by smoking status reveals an association of CHRNA5-A3-B4 genotype with body mass index in never smokers. PLoS Genet. 2014 Dec;10((12)):e1004799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu W, Liu H, Song F, Chen LS, Kraft P, Wei Q, et al. Associations between smoking behavior-related alleles and the risk of melanoma. Oncotarget. 2016 Jul;7((30)):47366–75. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P., 3rd Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;192:29–60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69248-5_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benowitz NL, Lessov-Schlaggar CN, Swan GE, Jacob P., 3rd Female sex and oral contraceptive use accelerate nicotine metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006 May;79((5)):480–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kandel DB, Hu MC, Schaffran C, Udry JR, Benowitz NL. Urine nicotine metabolites and smoking behavior in a multiracial/multiethnic national sample of young adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2007 Apr;165((8)):901–10. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnstone E, Benowitz N, Cargill A, Jacob R, Hinks L, Day I, et al. Determinants of the rate of nicotine metabolism and effects on smoking behavior. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Oct;80((4)):319–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higashi E, Fukami T, Itoh M, Kyo S, Inoue M, Yokoi T, et al. Human CYP2A6 is induced by estrogen via estrogen receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007 Oct;35((10)):1935–41. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramchandran K, Patel JD. Sex differences in susceptibility to carcinogens. Semin Oncol. 2009 Dec;36((6)):516–23. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Waal AC, van Rossum MM, Kiemeney LA, Aben KK. Reproducibility of self-reported melanoma risk factors in melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2014 Dec;24((6)):592–601. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holly EA, Kelly JW, Shpall SN, Chiu SH. Number of melanocytic nevi as a major risk factor for malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987 Sep;17((3)):459–68. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data