Since the first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was reported in the Republic of Korea on January 20th, 2020, a surge in cases has followed, resulting in 10,683 confirmed cases and 237 deaths, as of April 21st, 2020 [1]. Amid the global crisis caused by the pandemic, various public health interventions have been introduced in Korea from advice about social distancing, and personal hygiene, to testing for the virus, contact tracing, and isolation and quarantine measures [2,3].

Social distancing was initiated in South Korea in late February [4] and aimed to reduce disease transmission, thereby reducing pressure on the health services. Empirical evidence during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic has shown social distancing resulted in lowering the curve of the epidemic [5].

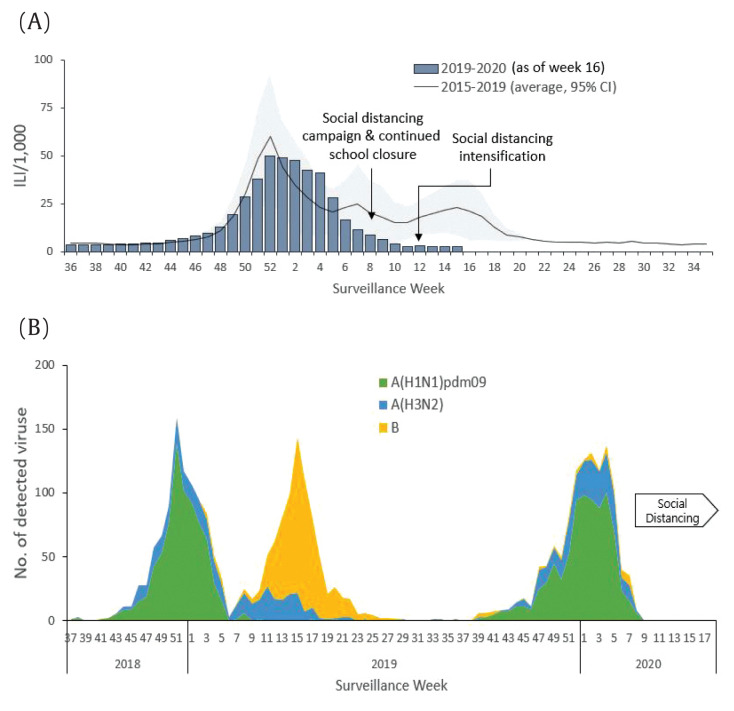

In South Korea, national surveillance of influenza comprises of 200 sentinel sites that report the percentage of visits to healthcare centers due to influenza-like-illness (ILI), and 52 sentinel sites that send respiratory specimens from patients with ILI to national laboratories [6]. Between the 2015–2016 and 2018–2019 flu seasons, there were multiple, distinctive waves of influenza epidemics (Figure 1A, line graph).

Figure 1.

(A) Impact of social distancing on influenza activity, and (B) on virus subtype detection in the Republic of Korea.

In response to the COVID-19 outbreak, civil movement and social distancing rules were implemented around late February, and included reminders regarding personal hygiene, avoiding mass gatherings, and emphasizing the staying-at-home message. On March 2nd, 2020, the government postponed the planned re-opening of schools, and on March 22nd, 2020, the government announced an intensified social distancing policy by recommending working from home, closure of religious facilities, bars, after-school clubs, and recreational facilities, and avoidance of mass gathering events. Since surveillance Week 6 of the 2019–2020 flu season, the percentage of patients with ILI decreased compared with the previous 4 flu seasons (Figure 1A). In the 2018–2019 flu season, after the first peak of influenza A (H1N1) had diminished during the surveillance Weeks 3–6, a second wave from influenza B and influenza A (H3N2) peaked during surveillance Weeks 9–19 (Figure 1B). In the 2019–2020 flu season, social distancing measures were imposed and a second wave of influenza virus was not observed.

The Korean national influenza virus surveillance data suggests that social distancing measures introduced in response to COVID-19 may have reduced the transmission of the virus and flattened the curve of the epidemic.

In a recent article, Cowling et al reported that non-pharmaceutical interventions were associated with a reduced transmission of COVID-19 and were also likely to have reduced transmission of the influenza in Hong Kong [7]. Nevertheless, surveillance of patients with ILI depends on these patients accessing healthcare, which may have been limited by social distancing and avoidance of seeking medical care. Evidence from other geographical regions could add validity to this finding and further highlight the role played by social distancing in the transmission of circulating respiratory viruses.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Central Disease Control Headquarters [Internet] Coronavirus Disease 2019, Republic of Korea. [cited 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/

- 2.COVID-19 National Emergency Response Center. Development and utilization of a rapid and accurate epidemic investigation support system for COVID-19. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11(3):118–27. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.3.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quarantine Management Team, COVID-19 National Emergency Response Center. Coronavirus Disease-19: Quarantine Framework for Travelers Entering Korea. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11(3):133–9. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.3.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan A, Liu L, Wang C, et al. Association of Public Health Interventions with the Epidemiology of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markel H, Lipman HB, Navarro JA, et al. Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. JAMA. 2007;298(6):644–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.6.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi WS. The National Influenza Surveillance System of Korea. Infect Chemother. 2019;51(2):98–106. doi: 10.3947/ic.2019.51.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowling BJ, Ali ST, Ng TWY, et al. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: An observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):E279–88. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]