Abstract

Background:

Poverty, unemployment, and substance abuse are interrelated problems. This study evaluated the effectiveness of abstinence-contingent wage supplements in promoting drug abstinence and employment in unemployed adults in outpatient treatment for opioid use disorder.

Methods:

A randomized controlled trial was conducted in Baltimore, MD from 2014–2019. After a 3-month abstinence initiation and training period, participants (N=91) were randomly assigned to a Usual Care Control group that received employment services or to an Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement group that received employment services plus abstinence-contingent wage supplements. All participants were invited to work with an employment specialist to seek employment in a community job for 12 months. Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants could earn training stipends for working with the employment specialist and wage supplements for working in a community job, but had to provide opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples to maximize pay.

Results:

Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants provided significantly more opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples than Usual Care Control participants (65% versus 45%; OR=2.29, 95% CI=1.22 to 4.30, p =.01) during the 12-month intervention. Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants were significantly more likely to have obtained employment (59% versus 28%; OR=3.88, 95% CI=1.60 to 9.41, p =.004) and lived out of poverty (61% versus 30%; OR=3.77, 95% CI=1.57 to 9.04, p =.004) by the end of the 12-month intervention than Usual Care Control participants.

Conclusion:

Abstinence-contingent wage supplements can promote drug abstinence and employment.

INTRODUCTION

Substance use disorders, like many health problems, are associated with poverty[1]. Heroin and cocaine use are important examples. Heroin and cocaine use are concentrated in people who live in poverty[2–5] and are common in people who are unemployed[6]. Poverty and unemployment have been difficult to address,[7–9] including in adults who have long histories of substance use and misuse[10, 11].

Two broad approaches could be used to address poverty-related health disparities like substance use disorders: proximal interventions that seek to promote health behaviors in low-income populations and distal interventions that seek to move low-income people out of poverty[1]. The therapeutic workplace could be an ideal intervention for individuals with substance use disorders who live in poverty because it includes both a proximal intervention to promote drug abstinence and a distal intervention to promote employment. The therapeutic workplace hires and pays unemployed adults with substance use disorders to work. To promote abstinence, employment-based reinforcement is arranged in which participants are required to provide drug-negative urine samples or take addiction-treatment medications to work and to earn maximum pay. Employment-based abstinence reinforcement is a kind of contingency management intervention. Contingency management interventions have been demonstrated as highly effective in the treatment of substance use disorders[12–14]. The therapeutic workplace includes two phases through which participants progress sequentially. In Phase 1, each participant’s “job” is to engage in job-skills training to prepare for employment. In Phase 2, participants perform real jobs.

We have developed three models of Phase 2 of the therapeutic workplace: the cooperative employer model, the social business model, and the wage supplement model. In all of these models, participants enroll in Phase 1 and then progress to Phase 2[15]. Under the cooperative employer model, employers agree to hire Phase 1 graduates but require that employees undergo random drug testing and remain abstinent to maintain employment. We have not yet evaluated the cooperative employer model. The social business model has been shown to be effective in promoting both drug abstinence and employment[16]. Social businesses are businesses that exist to address the needs of people who live in poverty[17]. A therapeutic workplace social business hires Phase 1 graduates into a social business and the therapeutic workplace social business maintains both employment-based abstinence reinforcement and employment. Although effective, a therapeutic workplace social business may have a limited capacity because it can only offer a limited number of employment opportunities. The wage supplement model seeks to address the limited capacity of social businesses by promoting employment in community jobs. Under the wage supplement model, Phase 1 graduates are offered abstinence-contingent wage supplements for maintaining drug abstinence and verified employment in a community job. The present study evaluated the effectiveness of the wage supplement model in promoting and maintaining drug abstinence and employment in unemployed adults in treatment for opioid use disorder.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted at the Center for Learning and Health on the Johns Hopkins Bayview Campus in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study (IRB00046990) and all participants provided written informed consent. Participants were recruited between November 2015 and April 2018 through community agencies that served the target population, street outreach, and a compensated referral system in which study participants were paid for successfully referring others to the study. Applicants were eligible for the study if they were 18 years or older, were unemployed, were enrolled in or eligible for methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment, provided an opioid-positive (i.e., opiates, methadone, or buprenorphine) urine sample, self-reported an interest in gaining employment, and lived in or near Baltimore City. Initially, applicants had to provide a urine sample positive for cocaine and report and show visible evidence (track marks) of injection drug use, but those requirements ended in June of 2016 to increase recruitment. Applicants were excluded if they reported current suicidal or homicidal ideation; had active hallucinations, delusions, or thought disorder; were currently considered a prisoner; and had physical limitations that prevented typing.

Study Design

This was a two-group randomized controlled trial. All participants completed a 90-day Phase 1 period and then were randomly assigned to one of two groups. After random assignment, participants completed a year-long Phase 2 period. We assessed all participants every month throughout Phases 1 and 2.

Pre-Randomization Procedures (Phase 1)

In Phase 1, all participants were invited to attend the therapeutic workplace for 90 days. Participants could attend the therapeutic workplace for 4 hours every weekday and could earn about $10 per hour. Participants could earn up to $8 per hour in base pay for every hour worked in the therapeutic and up to about $2 per hour in performance pay for work performed in the therapeutic workplace. Participants worked on computerized training programs designed to teach them basic computer and educational skills. Participants provided urine samples three times per week (typically Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays) under observation in private bathrooms located at the study site. The samples were then tested using Abbott Alere urine test cups (Model No. I-DX-1147-022) for metabolites of select drugs, including morphine (opiates) and benzoylecgonine (cocaine).

Initially, participants could attend the therapeutic workplace and earn maximum hourly pay regardless of whether their urine samples tested positive or negative for opiates and cocaine. This workplace induction lasted for 5 weeks. After the workplace induction, participants had to provide opiate-negative urine samples to maintain maximum pay. Under this opiate-abstinence contingency, if a participant failed to provide a scheduled urine sample or provided a urine sample that tested positive for opiates, that participant’s base pay was reset to $1 per hour. After being reset, base pay could be raised by $1 per hour (to a maximum of $8 per hour) every day that the participant provided an opiate-negative sample and worked for at least 5 min. After two weeks of exposure to the opiate-abstinence contingency, the abstinence contingency was extended to cocaine for the remainder of the 90-day period. Under this opiate- and cocaine-abstinence contingency, if a participant failed to provide a scheduled urine sample or provided a urine sample that tested positive for opiates or cocaine, that participant’s base pay was reset to $1 per hour. After being reset, base pay could be raised by $1 per hour (to a maximum of $8 per hour) every day that the participant provided an opiate- and cocaine-negative sample and worked for at least 5 min. For a detailed report of Phase 1, see[18].

Randomization

Participants who attended the therapeutic workplace on 10 out of the final 20 days of the 90-day Phase 1 period were invited to participate in Phase 2. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to one of two study groups using a computerized urn randomization procedure to balance groups on characteristics that could influence outcome: (1) had a high school diploma or GED (yes/no); (2) percentage of opiate-positive urine samples collected at monthly assessments throughout Phase 1 (percentage ≥ the rolling median, yes/no); (3) percentage of cocaine-positive urine samples collected at monthly assessments throughout Phase 1 (percentage ≥ the rolling median, yes/no). Various staff members involved in the protocol operated the randomization program. Participants were taught the details of their group with verbal and written instructions, and quizzes with incentives for correct responses.

Post-Randomization Procedures (Phase 2)

At the beginning of Phase 2, participants were randomly assigned to the Usual Care Control group or the Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement group. All participants could work with an employment specialist for one year who assisted participants in obtaining employment in a community job. The employment specialist implemented a variation of Individual Placement and Support,[19] which focused on promoting employment in competitive jobs that were selected based on client preferences. However, critical features of Individual Placement and Support were omitted. Most importantly, the employment specialists did not spend the majority of their time in the community, employment specialists did not establish relationships with employers, and participants were not referred to jobs identified by the employment specialists through their contacts with employers. Participants in the Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement group could earn abstinence-contingent stipends for working with the employment specialist and engaging in job-seeking behaviors for up to 20 hours per week (up to about $10 per hour). The stipends were divided into base pay (for hours worked) and performance pay (for engaging in job-seeking behaviors). When employed, those participants could earn abstinence-contingent wage supplements for all verified (by pay stubs) hours that they worked in a community job for up to 40 hours per week (up to $8 per hour). Stipends and wage supplements were funded solely by the study grant. To earn the maximum amount in base pay and wage supplements, participants had to provide opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples according to a routine, and then progressively more intermittent, random drug-testing schedule (described below).

Initially, participants were required to provide urine samples every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. After 30 days in which all mandatory samples met the abstinence criteria, a schedule was established in which an average of one of every two Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays were designated as mandatory collection and testing days. After every 30 days in which all mandatory samples met the abstinence criteria the average was reduced further by one, until an average of one of every six Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays were designated randomly as mandatory days. Participants could call the workplace to ask if that day’s urine sample collection was mandatory. If a urine sample was not mandatory on a given day, the participant was not required to provide a urine sample that day. If a participant provided a positive sample on a mandatory day or missed a mandatory sample, then that participant’s base pay or wage supplement was reset to $1 per hour and routine mandatory testing (i.e., every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) was reinstated and the schedule-thinning process repeated from the beginning. In addition, after being reset, the base pay or wage supplement could be raised by $1 per hour (to a maximum of $8 per hour) every day that the participant provided a drug (opiates and cocaine) negative urine sample and worked for at least 5 min.

Study Assessments

All participants were assessed at intake to the study and every month during Phases 1 and 2. At intake, we administered portions of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, second edition) to assess for opioid and cocaine use disorder;[20] a questionnaire to assess participants’ interest in gaining competitive employment; and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to screen for depression[21]. The following were administered at all assessments: collection and testing of urine samples for opiates (morphine concentrations with a positive/negative cut-off of 300 ng/ml), cocaine (benzoylecgonine concentrations with a positive/negative cut-off of 150 ng/ml), methadone (methadone concentrations with a positive/negative cut-off of 300 ng/ml), buprenorphine (buprenorphine glucuronide concentrations with a positive/negative cut-off of 10 ng/ml), benzodiazepines (oxazepam concentrations with a positive/negative cut-off of 300 ng/ml), oxycodone (oxycodone concentrations with a positive/negative cut-off of 100 ng/ml), and THC (11-nor-Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol-9-carboxylic acid concentrations with a positive/negative cut-off of 50 ng/ml); and the Addiction Severity Index–Lite (ASI–Lite)[22]. Additional exploratory assessments were collected but are not reported here. Participants earned $30 for intake and monthly assessments. Assessment payments were paid through reloadable credit cards.

Outcome Measures

The primary and secondary outcome measures were selected prior to beginning enrollment in the study and were based on data collected at the monthly assessments for both groups conducted throughout the year in Phase 2. The primary outcome measures were the percentage of opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples (urinary morphine and benzoylecgonine concentrations of less than 300 ng/ml and 150 ng/ml, respectively); and self-reports of employment (ever employed based on self-reported employment on the ASI–Lite). Secondary outcomes included whether each participant ever lived out of poverty, several injection-related HIV risk behaviors, and cost-benefit outcomes. Whether a participant was under or over the threshold for poverty was calculated using income and age data from the Addiction Severity Index-Lite and 2018 Poverty Thresholds from the US Census Bureau. The poverty threshold was based on the US Census Bureau poverty threshold for one person with no related children living in the home. Total income from the Addiction Severity Index-Lite included income from employment; unemployment compensation; welfare benefits; and pension, benefits, and social security. Earnings from Phase 1 training stipends and Phase 2 stipends for working with the employment specialist or wage supplements for community employment were not included in the total income calculations. For each monthly assessment, total income was calculated for the past 30 days. That value was then multiplied by 12 to estimate a total yearly income. That total yearly income was compared to the yearly income identified on the 2018 Poverty Thresholds from the US Census Bureau to determine if the participants had a total income that placed the person above or below the poverty threshold. The injection-related HIV risk behaviors are not reported because we discontinued the inclusion requirement for injection drug use (see above). The cost-benefit measures will be reported in a separate manuscript. Additional measures included the percentage of assessments collected, the percentage of months that participants reported being employed, the percentage of months that participants lived out of poverty, the average number of days that participants were paid for working, average employment earnings, and the percentage of workdays attending the therapeutic workplace.

Statistical Analyses

Measures assessed repeatedly over time were analyzed with a longitudinal logistic regression model. Within-person correlated outcomes were handled using the method of generalized estimating equations[23]. Measures assessed once were analyzed using logistic regression. The magnitude of effect was expressed using odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Intention-to-treat analyses were adjusted for covariates used for stratification[24]. All missing values were imputed as the adverse outcome (e.g., opiate- and cocaine-positive urine). Model parameter estimates from this approach were compared to a method without imputation (missing = missing analysis). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 (College Station, TX; StataCorp LLC) was used to perform these analyses.

We followed Liu and Liang to determine the total sample size required to detect a difference between groups with 80% power[25]. A sample size of 120 was expected to be sufficient to detect a difference of 15% between groups in the primary outcome measures collected at the 12 monthly assessments, using a within-person correlation of 0.69 and an AR1 correlation structure. We stopped recruitment after randomly assigning 91 participants to the study groups because of budgetary reductions that were outside of the control of the investigator.

Patient and Public Involvement

Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this manuscript for readability or accuracy. However, patients were invited to refer interested applicants to the study.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics and Flow through the Study

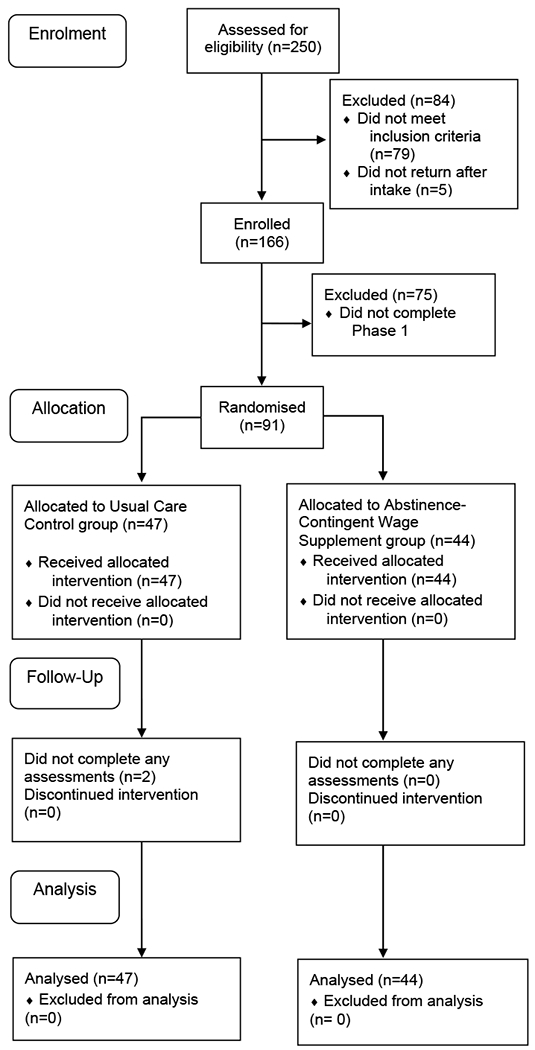

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through the study. Participants (N=91) who completed Phase 1 were invited to participate in Phase 2 and were randomly assigned to the Usual Care Control group (n=47) and the Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement group (n=44). For a detailed report of participants who did and did not complete Phase 1, see[18]. Participants in the two groups were an average (SD) of 47.1 (10.5) and 48.3 (10.3) years old, respectively. Table 1 shows participant characteristics assessed at intake to the study and during Phase 1 (before participants were randomized). A little over half of the participants identified as male and black. Almost all participants were living in poverty and most were usually unemployed during the past 3 years. All of the participants were enrolled in methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment. About half of the participants reported using heroin and cocaine in the past 30 days.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at study intake and during Phase 1 (before random assignment)

| Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|

| Usual Care Control (n=47) | Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement (n=44) | |

| Intake | ||

| Male | 57 | 52 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 49 | 64 |

| White | 47 | 32 |

| Other | 4 | 4 |

| Married | 15 | 18 |

| High school diploma or GED | 66 | 66 |

| Living in povertya | 98 | 98 |

| Ever incarcerated | 72 | 91 |

| Usual employment pattern, past 3 years | ||

| Unemployed | 81 | 66 |

| Employed – Full time | 15 | 20 |

| Employed – Part time | 4 | 14 |

| Used heroin, past 30 days | 55 | 57 |

| Used cocaine, past 30 days | 47 | 59 |

| Opiate- and cocaine-negative urine | 40 | 34 |

| Enrolled in opioid-substitution treatment | ||

| Methadone | 94 | 93 |

| Buprenorphine | 6 | 7 |

| Phase 1 | ||

| Days attended the therapeutic workplace | 82 | 87 |

| Opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples | 65 | 66 |

| Ever employed | 9 | 4 |

| Months employed | 4 | 2 |

| Ever living out of povertya | 9 | 6 |

| Months living out of povertya | 4 | 5 |

Poverty status was calculated using income and age data from the Addiction Severity Index-Lite and 2018 Poverty Thresholds from the US Census Bureau for one person with no related children.

Attendance in the Therapeutic Workplace during Phase 2

Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants attended the therapeutic workplace to work with the employment specialist on significantly more days than Usual Care Control participants (41.8% versus 1.1% of days; OR=40.42, 95% CI=32.46-48.38, p <.001). Whereas many Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants attended the therapeutic workplace and worked consistently with the employment specialist to look for a job, Usual Care Control participants stopped attending the therapeutic workplace and working with the employment specialist almost immediately after random assignment and enrollment in Phase 2.

Drug Abstinence during Phase 2

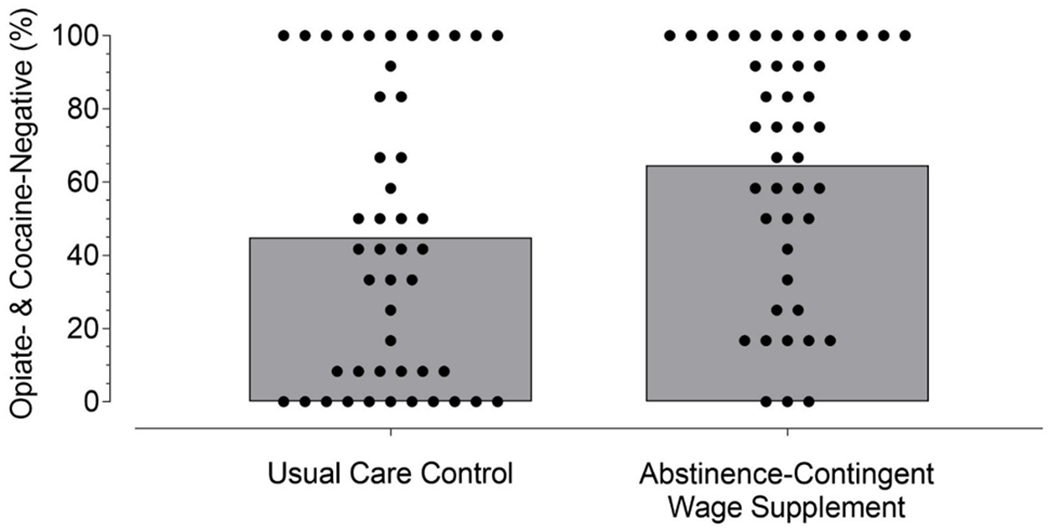

During the 12-month intervention period (Phase 2), Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants provided a significantly higher rate of urine samples negative for opiates and cocaine than Usual Care Control participants (Figure 2 and Table 2), with missing samples considered drug positive. The significant effects based on an analysis that ignored missing samples (missing=missing analysis) were identical (see Supplementary File 1).

Figure 2.

Percentage of opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples for participants in the Usual Care Control group and the Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement group collapsed across the 12-month intervention (Phase 2). Dots show percentages for individual participants and the top of the shaded bar graphs show group means. Missing samples were considered positive. The difference between groups was statistically significant (OR=2.29, 95% CI=1.22-4.30, p =.01).

Table 2.

Primary, secondary, and other outcome measures from monthly assessments conducted after random assignment during the 12-month Phase 2 period.

| Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Care Control | Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Primary Outcome Measures | ||||

| Opiate- and cocaine-negative urine | 44.9 | 64.6 | 2.29 (1.22-4.30) | .01 |

| Ever employed | 27.7 | 59.1 | 3.88 (1.60-9.41) | .004 |

| Secondary Outcome Measure | ||||

| Ever lived out of povertya | 29.8 | 61.4 | 3.77 (1.57-9.04) | .004 |

| Other Outcome Measures | ||||

| Months employed | 11.9 | 32.6 | 3.64 (1.69-7.83) | .001 |

| Months lived out of povertya | 9.6 | 23.3 | 2.87 (1.30-6.37) | .009 |

| Assessments collected | 89.4 | 95.3 | 2.49 (0.67-9.31) | .175 |

Poverty status was calculated using income and age data from the Addiction Severity Index-Lite and 2018 Poverty Thresholds from the US Census Bureau for one person with no related children.

Employment during Phase 2

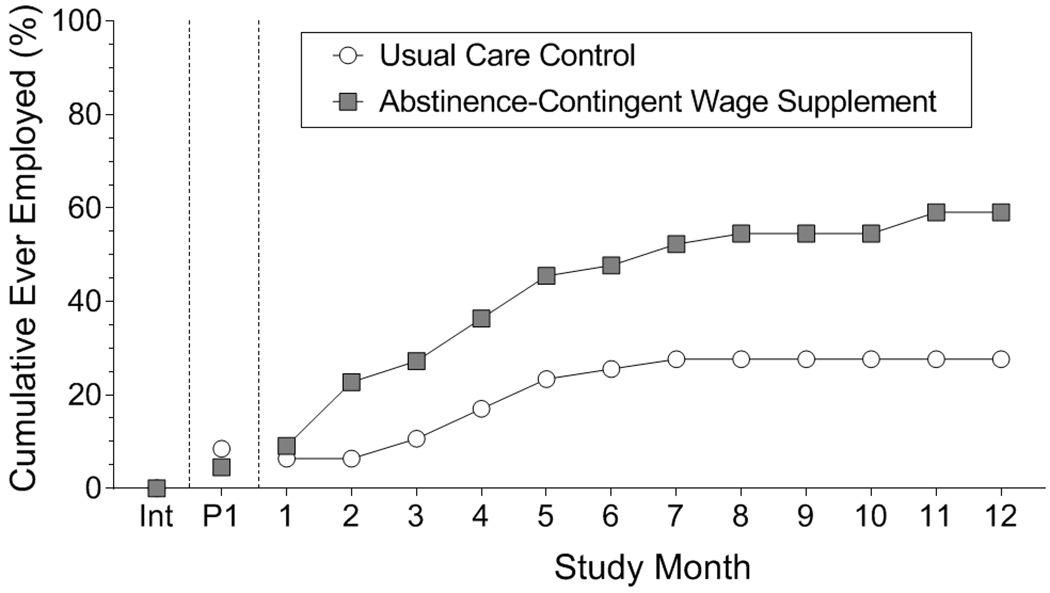

Figure 3 shows the cumulative percentage of participants who were ever employed during the study. A few participants obtained employment during Phase 1. By the end of the 12-month intervention period, 59.1% of the Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants were ever employed compared to 27.7% of the Usual Care Control participants. Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants were significantly more likely to have obtained employment by the end of the 12-month intervention than Usual Care Control participants (Figure 3 and Table 2), with missing data considered unemployed. The significant effects based on an analysis that ignored missing assessments (missing=missing analysis) were identical (see Supplementary File 1).

Figure 3.

Cumulative percentage of participants who were ever employed in the Usual Care Control group (circles) and the Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement group (squares) at intake (Int), during Phase 1 (P1), and across consecutive months during the intervention (Phase 2). Missing samples were coded as unemployed. The difference between groups at the end of Phase 2 was statistically significant (OR=3.88, 95% CI=1.60-9.41, p =.004).

During the 12 months after random assignment (Phase 2), Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants were employed in significantly more study months (32.6% of months) than Usual Care Control participants (11.9% of months; Table 2). Additionally, Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants worked more days per month than Usual Care Control participants (5.5 versus 1.7 days, on average, respectively; OR=3.81, CI=1.71-5.92, p <.001) and had higher employment earnings per month than Usual Care Control participants ($295 versus $111, on average, respectively; OR=183.18, CI=48.26-318.10, p =.008).

Poverty during Phase 2

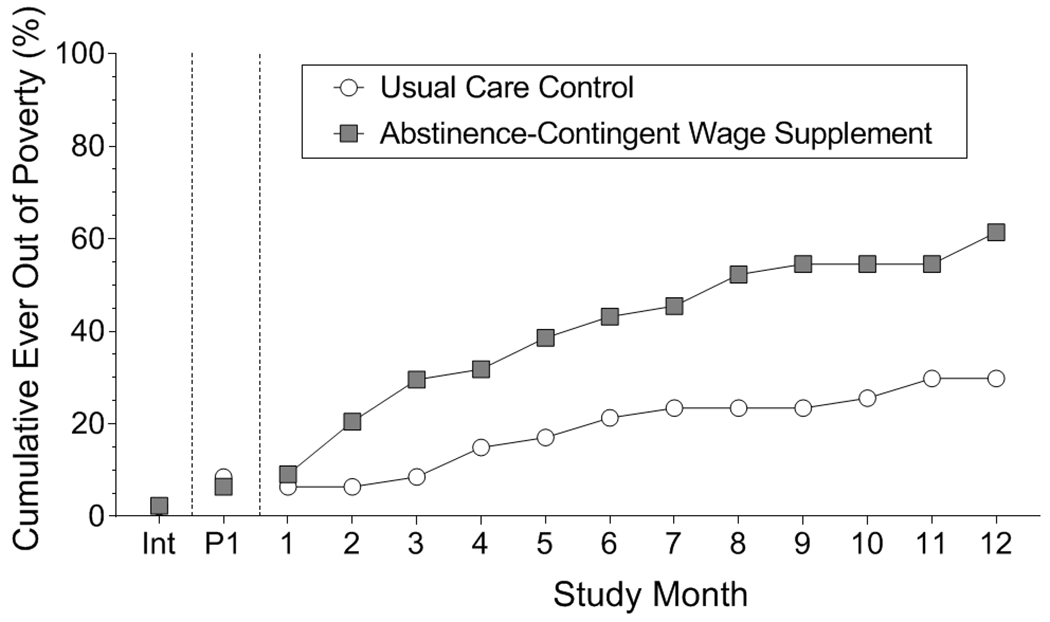

Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants were significantly more likely to have lived out of poverty by the end of the 12-month intervention (61.4% of participants) than Usual Care Control participants (29.8% of participants; Figure 4 and Table 2) with missing data considered living in poverty. During the 12 months after random assignment (Phase 2), Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants lived out of poverty on significantly more study months (23.3% of months) than Usual Care Control participants (9.6% of months; Table 2). The significant effects based on an analysis that ignored missing assessments (missing=missing analysis) were identical (see Supplementary File 1).

Figure 4.

Cumulative percentage of participants who ever lived out of poverty in the Usual Care Control group (circles) and the Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement group (squares) at intake (Int), during Phase 1 (P1), and across consecutive months during the intervention (Phase 2). Missing samples were coded as living in poverty. The difference between groups at the end of Phase 2 was statistically significant (OR=3.77, 95% CI=1.57-9.04, p =.004).

Stipend and Wage Supplement Earnings during Phase 2

Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants earned an average of $6,630 (SD=$3,785) in stipends and wage supplements during the 12-month intervention.

DISCUSSION

This randomized controlled trial showed that abstinence-contingent wage supplements can promote and maintain drug abstinence and employment in adults with opioid use disorder. All participants attended Phase 1 of the therapeutic workplace for 90 days, where they received training and experienced employment-based abstinence reinforcement designed to initiate opiate and cocaine abstinence. Participants who continued to attend the therapeutic workplace were offered access to an employment specialist for one year and assigned randomly to an Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement group or a Usual Care Control group. Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants could earn abstinence-contingent stipends for working with the employment specialist and abstinence-contingent wage supplements for working in a community job. Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants maintained significantly higher rates of opiate- and cocaine-negative urine samples and were significantly more likely to obtain employment than the Usual Care Control participants during the year-long intervention. Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants were also significantly more likely to live out of poverty than the Usual Care Control participants at some point during the year-long intervention. Finally, Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants also lived out of poverty in significantly more months than Usual Care Control participants.

Promoting employment in low-income adults with histories of substance use disorders is a difficult challenge for which existing interventions have been largely ineffective[10, 11, 26, 27]. The present study suggests that abstinence-contingent wage supplements in combination with employment services could be an effective approach to increase employment in adults with substance use disorders.

This result is promising, but there is room for improvement. After obtaining employment, few participants maintained stable employment and employment earnings were suboptimal. Although the abstinence-contingent wage supplement intervention reduced poverty, the majority of participants spent most months living in poverty. Moving most people out of poverty consistently will likely require promoting consistent employment in well-paying jobs. We suspect that we may achieve that goal best through the addition of education-focused interventions that seek to establish needed academic and job skills that might qualify individuals for consistent employment in well-paying jobs[28, 29]. If that is true, then approaches such as the stipend-supported computer-based training that we have provided using the software ATTAIN may be useful in establishing the needed skills[30, 31].

Results from the present study are consistent with prior research demonstrating that employment-based abstinence reinforcement is highly effective in promoting and maintaining drug abstinence in low-income adults with histories of substance use disorder[16, 32–39]. At study intake, relatively few participants (37%) provided urine samples that were negative for opiates and cocaine, whereas 65% tested opiate and cocaine negative after abstinence contingencies were applied. Participants provided significantly more drug-negative urine samples (65%) when employment-based abstinence reinforcement was maintained (Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants) than when it was not maintained (45%, Usual Care Control participants). The fact that employment-based abstinence reinforcement in the form of wage supplements can maintain drug abstinence is important because it could provide an effective way to support long-term abstinence and prevent relapse, at least as long as employment and wage supplements are maintained.

Special contingencies may be needed to promote job-seeking and work behaviors in many adults with histories of unemployment and substance misuse. All participants were offered access to an employment specialist who helped them find and obtain a community job. Most Abstinence-Contingent Wage Supplement participants, who could earn incentives for working with the employment specialist, worked with the employment specialist consistently, whereas most Usual Care Control participants stopped working with the employment specialist shortly after randomization. This is consistent with prior studies demonstrating the utility of incentives in promoting attendance and performance in job-skills training programs for unemployed adults with substance use disorders[40]. Those studies have shown that unemployed adults will attend a job-skills training program primarily when offered incentives for attendance;[36, 41, 42] and they will work on training programs, but primarily when offered incentives based on their performance on the training programs[43, 44].

The present study demonstrated that a treatment package of three elements increased employment and drug abstinence, but we do not know which element was critical or whether all elements were necessary. The elements included employment services, abstinence-contingent stipends for working with an employment specialist, and abstinence-contingent wage supplements for working in a community job. Because Usual Care Control participants were offered employment services and chose not to utilize those services, we can safely conclude that employment services alone were not effective for this population. However, we may have achieved similar results, for example, if we only offered abstinence-contingent stipends for working with the employment specialist or if we only offered abstinence-contingent wage supplements for maintaining community employment. We cannot know from this study which element or combination of elements produced the drug abstinence or employment outcomes.

The development of interventions that can address the interrelated problems of substance use and poverty are among the most important challenges in substance abuse treatment research. The therapeutic workplace could be an ideal intervention for individuals with substance use disorders who live in poverty because it includes both a proximal intervention to promote drug abstinence and a distal intervention to promote employment[1, 40]. It also provides an opportunity to arrange special contingencies that may be needed to promote skill development, job-search behaviors, and employment in this population. The therapeutic workplace wage supplement model could expand employment opportunities and provide a viable means of arranging employment-based abstinence reinforcement as a long-term intervention to support recovery and prevent relapse, and alleviate poverty-related health disparities.

Supplementary Material

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOW ON THIS TOPIC

Poverty is a major risk factor underlying poor health and is prevalent among people who have substance use disorder

Existing interventions have been largely ineffective in addressing poverty, particularly in people with substance use disorder

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This randomized controlled trial showed that abstinence-contingent wage supplements can promote and maintain drug abstinence and employment in adults with opioid use disorder Abstinence-contingent wage supplements could be applied to address the interrelated problems of poverty and substance use disorder

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to Robert Drake and Lawrence Abramson, who provided guidance on Individual Placement and Support (IPS) supported employment; Jacqueline Hampton, who recruited participants for this study and conducted outcome assessments; Meghan Arellano, who provided employment services to participants; Andrew Rodewald, who managed our therapeutic workplace and urinalysis laboratory; and Calvin Jackson, who taught participants the details of their group and monitored participants while in the therapeutic workplace.

Role of the funding source: The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under grants R01 DA037314 and T32 DA07209. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The National Institutes of Health had no part in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Competing interest: None declared.

Transparency declaration: Holtyn and Silverman affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Ethical approval: The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study (IRB00046990) and all participants provided written informed consent to take part in the study.

References

- 1.Silverman K, Holtyn AF, Toegel F. The Utility of Operant Conditioning to Address Poverty and Drug Addiction. Perspectives on Behavior Science. 2019:1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong GL. Injection drug users in the United States, 1979-2002: an aging population. Archives of internal medicine. 2007;167(2):166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CBHSQ. 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2018.

- 4.Rosenthal A, Bol KA, Gabella B. Examining Opioid and Heroin-Related Drug Overdose in Colorado: Colorado: Department of Public Health and Environment, Office of eHealth and Data; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams CT, Latkin CA. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, personal network attributes, and use of heroin and cocaine. American journal of preventive medicine. 2007;32(6):S203–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henkel D. Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990-2010). Current drug abuse reviews. 2011;4(1):4–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bitler MP, Karoly LA. Intended and unintended effects of the war on poverty: What research tells us and implications for policy. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2015;34(3):639–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holtyn AF, Jarvis BP, Silverman K. Behavior analysts in the war on poverty: A review of the use of financial incentives to promote education and employment. Journal of the experimental analysis of behavior. 2017;107(1):9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman K, Holtyn AF, Jarvis BP. A potential role of anti-poverty programs in health promotion. Preventive medicine. 2016;92:58–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Magura S, Staines GL, Blankertz L, Madison EM. The effectiveness of vocational services for substance users in treatment. Substance use & misuse. 2004;39(13-14):2165–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svikis DS, Keyser-Marcus L, Stitzer M, Rieckmann T, Safford L, Loeb P, et al. Randomized multi-site trial of the Job Seekers’ Workshop in patients with substance use disorders. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2012;120(1-3):55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis DR, Kurti AN, Skelly JM, Redner R, White TJ, Higgins ST. A review of the literature on contingency management in the treatment of substance use disorders, 2009–2014. Preventive medicine. 2016;92:36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilling S, Strang J, Gerada C. Psychosocial interventions and opioid detoxification for drug misuse: summary of NICE guidance. Bmj. 2007;335(7612):203–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silverman K, Holtyn AF, Morrison R. The therapeutic utility of employment in treating drug addiction: Science to application. Translational issues in psychological science. 2016;2(2):203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aklin WM, Wong CJ, Hampton J, Svikis DS, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, et al. A therapeutic workplace for the long-term treatment of drug addiction and unemployment: Eight-year outcomes of a social business intervention. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2014;47(5):329–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yunus M Creating a world without poverty: Social business and the future of capitalism: Public Affairs; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toegel F Effects of time-based administration of abstinence reinforcement targeting opiate and cocaine use. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drake RE, Bond GR, Becker DR. Individual placement and support: an evidence-based approach to supported employment: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Compton WM, Cottler LB, Dorsey KB, Spitznagel EL, Magera DE. Comparing assessments of DSM-IV substance dependence disorders using CIDI-SAM and SCAN. Drug and alcohol dependence. 1996;41(3):179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio. 1996;78(2):490–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr HL, et al. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeger SL, Liang K-Y, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988:1049–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practiceand problems. Statistics in medicine. 2002;21(19):2917–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu G, Liang K-Y. Sample size calculations for studies with correlated observations. Biometrics. 1997:937–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saal S, Forschner L, Kemmann D, Zlatosch J, Kallert TW. Is employment-focused case management effective for patients with substance use disorders? Results from a controlled multi-site trial in Germany covering a 2-years-period after inpatient rehabilitation. BMC psychiatry. 2016;16(1):279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAMHSA. Substance Use Disorders Recovery with a Focus on Employment and Education. Subtance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2019(HHS Publication No. PEP19-SUDEMPED). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holtyn AF, DeFulio A, Silverman K. Academic skills of chronically unemployed drug-addicted adults. Journal of vocational rehabilitation. 2015;42(1):67–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sigurdsson SO, Ring BM, O’Reilly K, Silverman K. Barriers to employment among unemployed drug users: Age predicts severity. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2012;38(6):580–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Getty C-A, Subramaniam S, Holtyn AF, Jarvis BP, Rodewald A, Silverman K. Evaluation of a computer-based training program to teach adults at risk for HIV about pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2018;30(4):287–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Subramaniam S, Getty C-A, Holtyn AF, Rodewald A, Katz B, Jarvis BP, et al. Evaluation of a computer-based HIV education program for adults living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2019:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeFulio A, Donlin WD, Wong CJ, Silverman K. Employment-based abstinence reinforcement as a maintenance intervention for the treatment of cocaine dependence: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donlin WD, Knealing TW, Needham M, Wong CJ, Silverman K. Attendance rates in a workplace predict subsequent outcome of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in methadone patients. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41(4):499–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holtyn AF, Koffarnus MN, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO, Strain EC, Schwartz RP, et al. The therapeutic workplace to promote treatment engagement and drug abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users: A randomized controlled trial. Preventive medicine. 2014;68:62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holtyn AF, Koffarnus MN, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO, Strain EC, Schwartz RP, et al. Employment-based abstinence reinforcement promotes opiate and cocaine abstinence in out-of-treatment injection drug users. Journal of applied behavior analysis. 2014;47(4):681–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koffarnus MN, Wong CJ, Diemer K, Needham M, Hampton J, Fingerhood M, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a therapeutic workplace for chronically unemployed, homeless, alcohol-dependent adults. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2011;46(5):561–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverman K, Svikis D, Robles E, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: six-month abstinence outcomes. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2001;9(1):14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silverman K, Svikis D, Wong CJ, Hampton J, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A reinforcement-based therapeutic workplace for the treatment of drug abuse: three-year abstinence outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002;10(3):228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silverman K, Wong CJ, Needham M, Diemer KN, Knealing T, Crone-Todd D, et al. A randomized trial of employment-based reinforcement of cocaine abstinence in injection drug users. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40(3):387–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverman K, Holtyn AF, Subramaniam S. Behavior analysts in the war on poverty: Developing an operant antipoverty program. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2018;26(6):515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koffarnus MN, Wong CJ, Fingerhood M, Svikis DS, Bigelow GE, Silverman K. Monetary incentives to reinforce engagement and achievement in a job-skills training program for homeless, unemployed adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46(3):582–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silverman K, Chutuape MAD, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of attendance by unemployed methadone patients in a job skills training program. Drug and alcohol dependence. 1996;41(3):197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koffarnus MN, DeFulio A, Sigurdsson SO, Silverman K. Performance pay improves engagement, progress, and satisfaction in computer-based job skills training of low-income adults. Journal of applied behavior analysis. 2013;46(2):395–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Subramaniam S, Everly JJ, Silverman K. Reinforcing productivity in a job-skills training program for unemployed substance-abusing adults. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice. 2017;17(2):114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.