Abstract

Biased signaling, where different ligands that bind to the same G-protein-coupled receptor preferentially trigger distinct signaling pathways, holds great promise for the design of safer and more effective drugs. Its structural mechanism remains unclear, however, hampering efforts to design drugs with desired signaling profiles. Here, we use extensive atomic-level molecular dynamics simulations to determine how arrestin bias and G-protein bias arise at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. The receptor adopts two major signaling conformations, one of which couples almost exclusively to arrestin, while the other also couples effectively to a G protein. A long-range allosteric network allows ligands in the extracellular binding pocket to favor either of the two intracellular conformations. Guided by this computationally determined mechanism, we design ligands with desired signaling profiles.

One sentence summary:

Simulations enable rational design of biased ligands by revealing how ligands select among signaling conformations of a GPCR.

Binding of an extracellular agonist to a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) generally stimulates multiple intracellular signaling pathways by causing the GPCR to couple to both G proteins and arrestins. GPCRs represent the targets of roughly one-third of all drugs (1), and in many cases, the desired effects of a drug stem from arrestin signaling and the undesired ones from G-protein signaling, or vice versa. Intriguingly, certain GPCR ligands preferentially stimulate either arrestin or G-protein signaling, a phenomenon known as biased signaling (2).

The molecular mechanism of biased signaling remains unknown, hindering the discovery and optimization of biased ligands that are more effective and have fewer side effects than conventional drugs. Biophysical studies indicate that ligands with distinct bias profiles stabilize distinct receptor conformations (3, 4), but these studies do not identify what these conformations are or how ligands induce them. The receptor adopts similar conformations in experimental structures of GPCR–G protein (5–9) and GPCR–arrestin (10–12) complexes, leaving unclear what intracellular conformations are responsible for biased signaling and how ligands in the extracellular binding pocket select among the relevant signaling conformations.

The angiotensin II (AngII) type 1 receptor (AT1R) is a model system for studies of biased signaling (13–15). It stimulates both G-protein-mediated and arrestin-mediated signaling pathways upon binding of its native ligand, the octapeptide AngII. Small modifications to AngII can result in either arrestin-biased or G-protein-biased ligands, which induce a higher or lower ratio of arrestin signaling to G-protein signaling than AngII, respectively (13, 14). AT1R is also a major drug target, and there is interest in developing arrestin-biased AT1R ligands as drugs for heart failure, because such ligands can increase cardiac contractility without undesired hypertensive effects (16–18).

The companion manuscript (19) presents crystal structures of AT1R bound to AngII and to arrestin-biased agonists. The intracellular conformations in these structures and in the previously published active-state structure (20) are essentially identical, most likely because they are all stabilized for crystallography by binding to the same high-affinity nanobody on the intracellular side. To determine how differences in intracellular conformation relate to the bias profile of the bound ligand, we performed extensive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of AT1R without the nanobody.

AT1R transitions between two active intracellular conformations

Our simulations were initiated from the previously published active-state AT1R structure (20), with the nanobody removed. In most of these simulations, the co-crystallized ligand was removed, and different ligands were modeled in its place, including AngII, four arrestin-biased ligands, and two G-protein-biased ligands (Table S1, Fig. S1). We also performed control simulations from the structures reported in the companion manuscript (19), and these simulations converged to the same behavior.

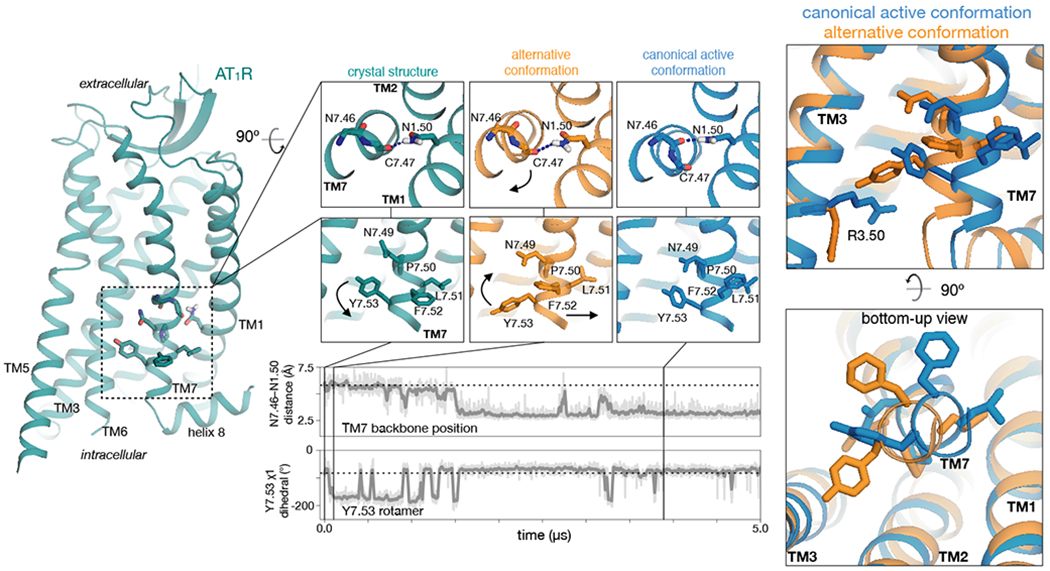

In simulations with the nanobody removed, agonist-bound AT1R transitions between two intracellular conformations that differ primarily in transmembrane helix 7 (TM7) (Fig. 1, Fig. S2). One of these, the “canonical active” conformation, closely resembles previously determined structures of GPCRs in complex with G proteins (5–9) as well as the active-state structure of the AngII type 2 receptor (AT2R) (21). The other—the “alternative” conformation—differs in several regards. Viewed from the extracellular side, TM7 is twisted counterclockwise above its proline kink, causing N1.50 (N46) to switch its preferred hydrogen-bond acceptor from N7.46 (N295) to C7.47 (C296). (We use the Ballesteros-Weinstein numbering scheme, where the digit before the decimal point specifies the TM helix (22).) As a result of this twist, the intracellular portion of TM7 shifts toward TM3, causing the side chains of Y7.53 (Y302) of the NPxxY motif and R3.50 (R126) of the DRY motif to adopt “downward” rotamers pointing toward the intracellular side. Interestingly, the nanobody-bound AT1R structures resemble the alternative intracellular conformation, except that Y7.53 adopts the upward rotamer of the canonical active conformation because its downward rotamer would clash with the nanobody.

Fig. 1. In simulation, AT1R adopts two major signaling conformations.

In a representative simulation with the nanobody removed, AT1R first adopts the “alternative” conformation and then transitions to the “canonical active” conformation. During this transition, TM7 twists above its proline kink, leading the intracellular portion of TM7 to shift away from TMs 2 and 3. The twisting motion causes N1.50 to switch its preferred hydrogen bond acceptor from C7.47 to N7.46 (top trace, distance between N1.50 side-chain nitrogen and N7.46 backbone oxygen). The conformational transition also leads to rearrangements of side chains, including those of Y7.53 and R3.50, which are oriented downward (toward the intracellular side) in the alternative conformation and more upward in the canonical active conformation (bottom trace; see also Fig. S3). Thick traces represent moving averages, while thin traces represent original, unsmoothed values (see Methods). Dashed horizontal lines indicate values for the nanobody-bound crystal structures.

Both the alternative and canonical active conformations retain the TM6 conformation observed in the nanobody-bound AT1R structures (19, 20), which is characteristic of active-state GPCR structures in that it is shifted outward relative to inactive-state structures (23, 24).

Unlike the canonical active conformation, the alternative conformation has not been observed in experimental GPCR structures. The alternative conformation of TM7 closely resembles several GPCR structures (Fig. S2) (25–30), including the serotonin 2B receptor (5-HT2BR) bound to arrestin-biased ligands. However, these structures exhibit more inactive-like positions of TM6, likely owing to the absence of intracellular binding partners. In previous simulations of the β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR) transitioning from its canonical active to inactive conformation, we observed a rare intermediate in which both TM6 and TM7 match the alternative conformation, but we did not suggest a connection to biased signaling (31).

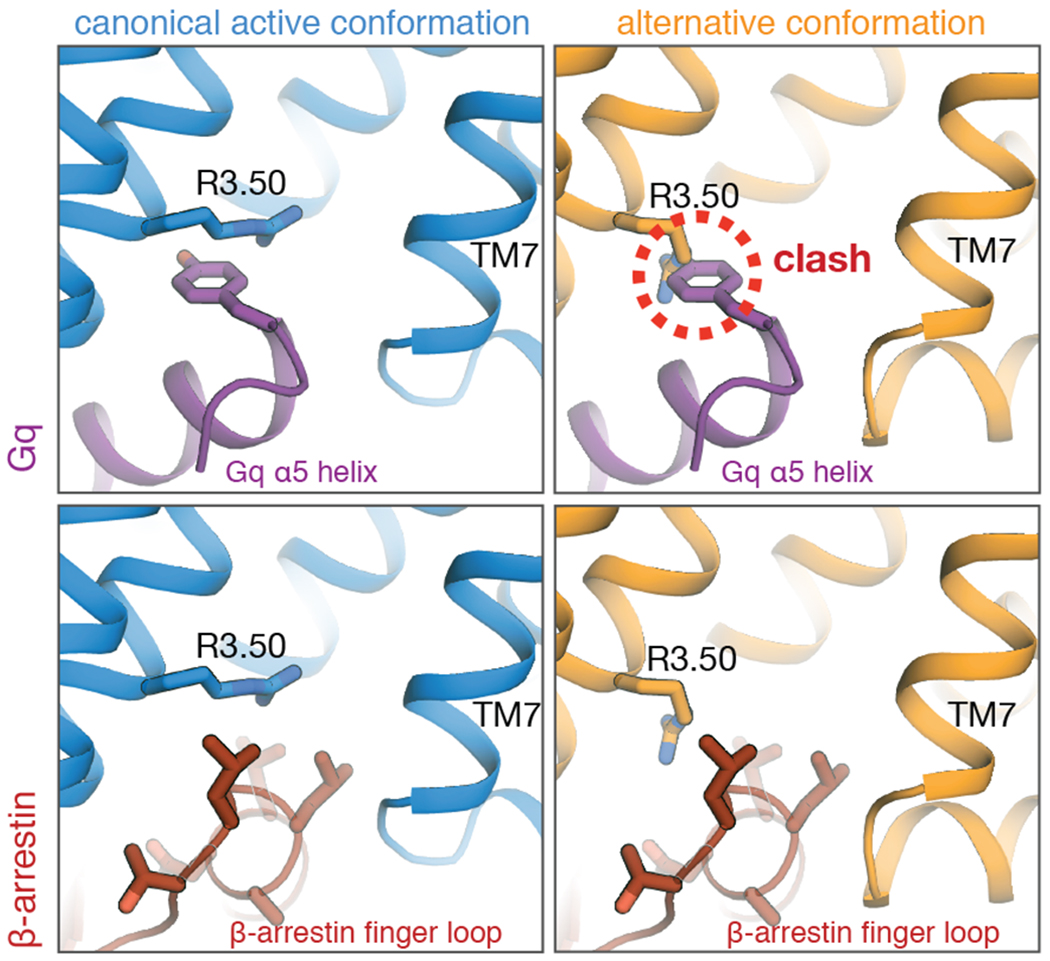

The alternative conformation appears to accommodate β-arrestins but not Gq

To determine whether these two conformations couple differently to G proteins and arrestins, we prepared structural models of AT1R in complex with its preferred partners, Gq and β-arrestin 1/2 (Fig. 2). These models suggest that, while the canonical active conformation couples well to both Gq and β-arrestins, the alternative conformation couples well to β-arrestins but not Gq. The alternative conformation stabilizes R3.50 in a downward rotamer, which clashes with the α5 helix of Gq. R3.50 shifts upward upon transition to the canonical active conformation, accommodating insertion of the Gα subunit. Both the alternative and canonical active conformations appear to readily accommodate the β-arrestin finger loop.

Fig. 2. Structural models suggest that the alternative conformation couples preferentially to β-arrestins, while the canonical active conformation couples well to both Gq and β-arrestins.

In the alternative conformation, R3.50 adopts an orientation that clashes with a tyrosine on the α5 helix of Gq (top right). The bottom row shows models with β-arrestin 1; models with β-arrestin 2 yield essentially identical results (see Methods).

In simulations of rhodopsin bound to visual arrestin, rhodopsin occasionally transitions spontaneously from the canonical active conformation to the alternative conformation, with both R3.50 and Y7.53 forming interactions with backbone atoms on the finger loop (Fig. S4). This indicates that both canonical active and alternative conformations of rhodopsin couple to arrestin.

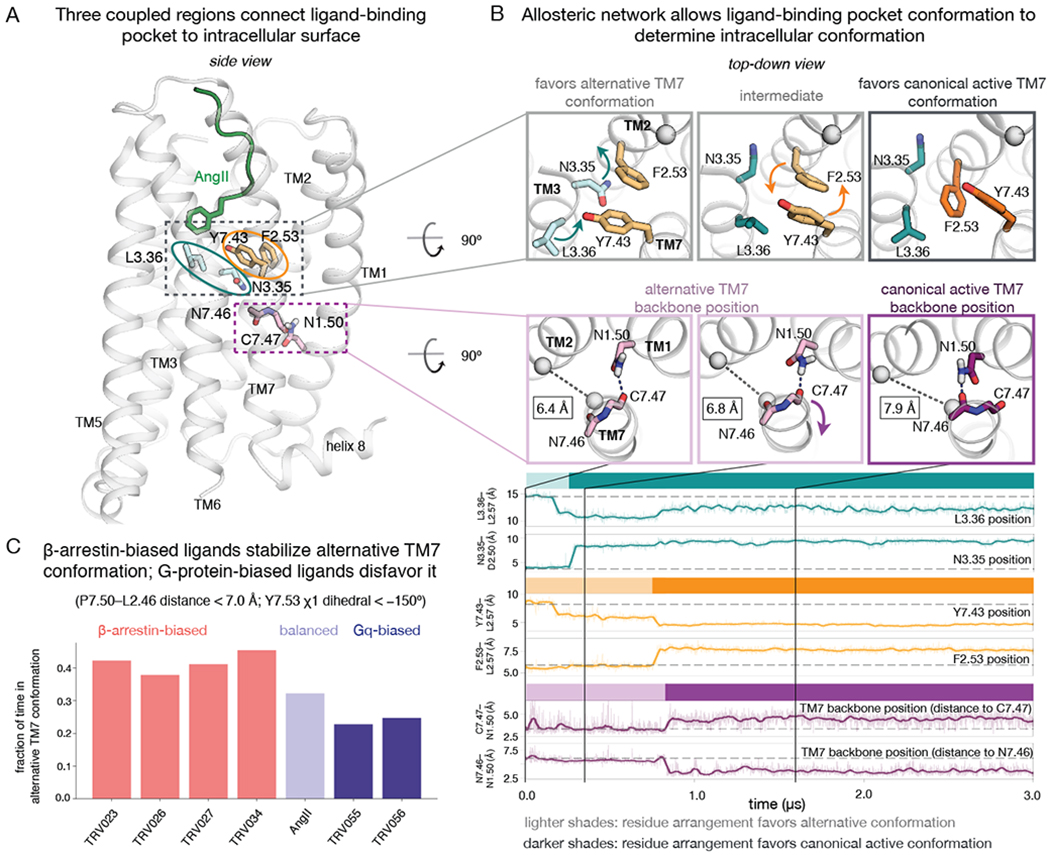

Intracellular TM7 conformation is allosterically coupled to ligand-binding pocket

In simulations that transition between the alternative and canonical active conformations, we observed rearrangements in several residues that form an allosteric network between the ligand-binding pocket and the intracellular side of the receptor (Fig. 3A, Fig. S5). The intracellular TM7 conformation is closely coupled to the position of Y7.43 (Y292) higher on TM7. The alternative conformation is favored when Y7.43 points toward TM3, and the canonical active conformation is favored when Y7.43 points toward TM2 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Allosteric network allows ligands to favor either intracellular conformation.

(A) Three coupled regions of AT1R connect the ligand-binding pocket to the intracellular surface. Key residues for the three regions are shown in turquoise, orange, and purple, respectively. (B) Mechanism for coupling between the three regions. In simulations that transition from the alternative conformation to the canonical active conformation, a rotation of TM3 at the binding pocket triggers subsequent rearrangements in other regions of the protein (top row, left and middle panels). Such transitions typically begin when L3.36 moves closer to TM2 (top turquoise trace) and N3.35 flips outward from the helical bundle (bottom turquoise trace). The outward displacement of N3.35 creates space for F2.53 to switch positions with Y7.43 (orange traces) (top row, middle and right panels). The motion of Y7.43 leads TM7 to twist just above its proline kink (bottom row, all panels), such that N7.46 replaces C7.47 as the hydrogen bonding partner of N1.50 (purple traces). This TM7 twist also leads to an outward shift of TM7 on the intracellular side, as measured by increasing P7.50–L2.46 Cα–Cα distances; these distances are shown in black rectangles in the bottom row of molecular renderings. See also Fig. S5. (C) In simulation, the fraction of time spent in the alternative TM7 conformation correlates with the ligand’s bias profile. β-arrestin-biased ligands favor this conformation much more than Gq-biased ligands (P = 0.0006, two-sided t-test; see Methods), and also more than the balanced ligand AngII (P = 0.007), which favors it more than Gq-biased ligands (P = 0.04). Reported values are based on REMD simulations of AT1R bound to each ligand. We performed two REMD simulations for AngII (with very similar results of 0.32 and 0.33, respectively), and one for each other ligand. Each REMD simulation consists of 36 coupled MD simulations, each 3.6 μs in length (see Methods).

Y7.43 is coupled to the ligand via two adjacent residues on TM3, N3.35 (N111) and L3.36 (L112) (Fig. 3A, B). When N3.35 points inward (toward the center of the helical bundle), Y7.43 nearly always points toward TM3. N3.35 must point outward for Y7.43 to point toward TM2, which requires that the side chains of Y7.43 and F2.53 (F77) swap positions (Fig. 3B). L3.36, which is often in direct contact with ligands, influences the position of neighboring residue N3.35: TM5- and TM2-proximal positions of L3.36 favor the inward- and outward-pointing positions of N3.35, respectively. L3.36 and Y7.43 can also interact directly, so repositioning of L3.36 also has some direct effect on Y7.43 conformation.

Arrestin-biased ligands favor the alternative conformation; Gq-biased ligands favor the canonical active conformation

In replica exchange MD (REMD) simulations designed to sample efficiently the conformational ensemble of AT1R bound to each ligand, we found that TM7 adopted the alternative conformation more frequently with arrestin-biased ligands bound than with AngII bound, and more frequently with AngII bound than with Gq-biased ligands bound (Fig. 3C). Combined with our observation that the alternative conformation preferentially binds arrestin, this suggests that ligands achieve arrestin bias by favoring the alternative conformation and G-protein bias by favoring the canonical active conformation.

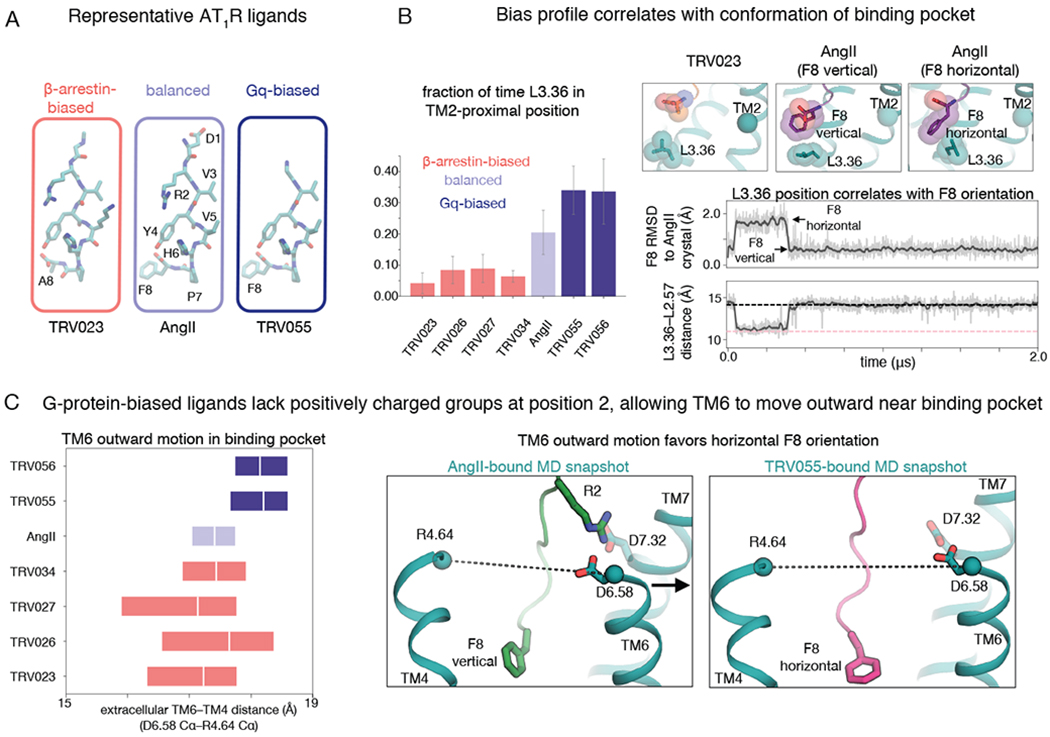

Ligands select among the alternative and canonical active conformations through the allosteric network described above. In simulation, L3.36 of the ligand-binding pocket was shifted toward TM2 more frequently with AngII than with arrestin-biased ligands, and even more frequently with Gq-biased ligands (Fig. 4B). The arrestin-biased ligands extend much less deeply into the binding pocket (Fig. 4A, Fig. S1), so they cannot readily push L3.36 toward TM2. In contrast, AngII and the Gq-biased ligands possess a bulky phenylalanine at position 8 and thus tend to push L3.36 toward TM2.

Fig. 4. Arrestin-biased, balanced, and G-protein-biased ligands favor distinct binding-pocket conformations.

(A) Structures of representative β-arrestin-biased, balanced, and Gq-biased AT1R ligands. All ligands studied in this work are shown in Fig. S1. (B) In comparison to β-arrestin-biased ligands, AngII drives L3.36 of the binding pocket toward its TM2-proximal position, which favors the canonical active conformation, and Gq-biased ligands do so even more (P = 0.002 for β-arrestin-biased vs. Gq-biased ligands; see Methods) (left; the bar plot shows means and standard errors across 5 independent 2-μs simulations per ligand). When the F8 residue of AngII and Gq-biased ligands adopts a horizontal orientation, it pushes L3.36 toward the TM2-proximal position (right; gray and pink dashed lines indicate values for TRV023- and AngII-bound structures, respectively; traces are for a simulation with AngII bound, and additional simulation traces are shown in Fig. S6). RMSD is root-mean-square deviation (see Methods). (C) AngII and β-arrestin-biased ligands stabilize more inward TM6 positions in the binding pocket compared to positions favored by Gq-biased ligands (P = 0.005 for Gq-biased ligands vs. AngII; P = 0.001 for Gq-biased ligands vs. β-arrestin-biased ligands), as shown by the box plot at left (boxes extend from 25th to 75th percentile of simulation frames), because the ligand R2 residue interacts with D6.58 and D7.32 (right; dashed lines correspond to distance plotted at left). The more outward position of the extracellular portion of TM6 observed for Gq-biased ligands allows their F8 residue to adopt a horizontal orientation more frequently than that of AngII (see also Fig. S7).

Our simulations indicate that the F8 residue of AngII and the Gq-biased ligands adopts distinct orientations with distinct effects on L3.36 (Fig. 4B, Fig. S6, Fig. S7). When L3.36 is in the TM5-proximal position that favors the alternative conformation, F8 tends to be vertical (i.e., the ring plane is perpendicular to the membrane plane), packing tightly above L3.36 (Fig. 4B, Fig. S6). When F8 instead adopts a horizontal orientation, it forces L3.36 toward TM2, which in turn favors the canonical active conformation as described above.

In simulation, Gq-biased ligands adopted the horizontal F8 orientation more frequently than AngII (Fig. S7). This is likely because, at AngII and arrestin-biased ligands, a positively charged arginine at position 2 (R2) engages negatively charged binding pocket residues D6.58 (D263) and D7.32 (D281), pulling the extracellular end of TM6 inward. The Gq-biased ligands lack a positively charged residue at position 2, and as a result, the extracellular end of TM6 tends to move outward, creating more space within the binding pocket for F8 to adopt a horizontal orientation (Fig. 4C).

The crystal structures in the companion manuscript (19) support this biased signaling mechanism, which we identified using simulations initiated from the previously published active-state structure (20). These crystal structures are locked into a single intracellular conformation, but in the structures with arrestin-biased ligands bound, residues near the binding pocket—N3.35, L3.36, and Y7.43—adopt positions that favor the alternative conformation in simulation. In the AngII-bound structure, on the other hand, N3.35 adopts a position (Fig. S8) that favors the canonical active conformation in simulation. The density for L3.36 in this structure is weak, suggesting that this residue adopts multiple conformations, and Y7.43 is so mobile that it cannot be resolved at all.

In agreement with our computational results, our recent double electron-electron resonance (DEER) spectroscopy study of AT1R (4) suggested that arrestin-biased, balanced, and G-protein-biased ligands stabilize subtly different intracellular TM7 conformations. The DEER data also show differences in helix 8 position, which are likely due to these conformational changes in TM7. Differences in TM6 position might be due to adoption of the TM6-bent conformation discussed below. The DEER data suggest that the receptor undergoes additional ligand-dependent conformational changes on timescales longer than those of our simulations, although changes in other receptor regions may not be relevant to biased signaling. For example, although the various arrestin-biased ligands stabilize diverse conformations in DEER experiments, these ligands have very similar pharmacological bias profiles. Their pharmacological profiles are consistent with our simulations, which indicate that the various arrestin-biased ligands stabilize the alternative TM7 conformation to a similar degree.

Computational design of ligands with desired biased signaling profiles

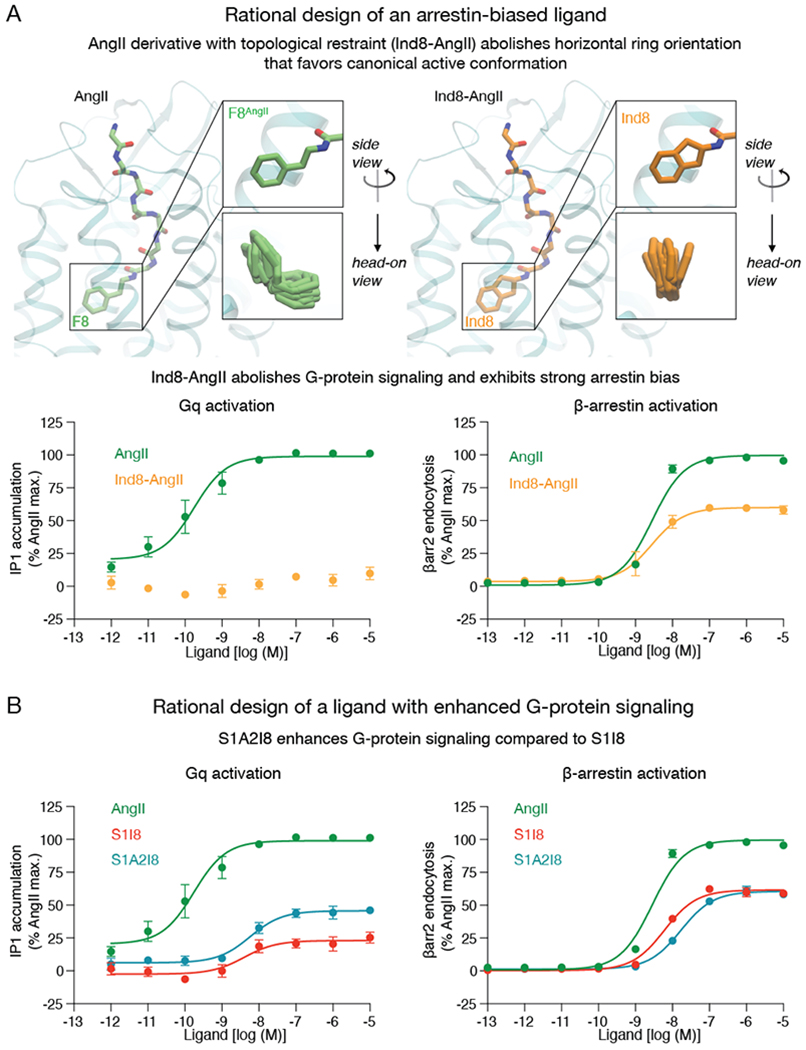

To further validate our computationally determined mechanism, we used it to design ligands with desired biased signaling profiles (Fig. 5), a long-standing challenge in GPCR drug discovery.

Fig. 5. Rational design of ligands with desired signaling profiles.

(A) The addition of a single connecting methylene group to the phenyl moiety of AngII ligand restrains the C-terminal ring to remain vertical, producing a strongly arrestin-biased ligand, Ind8-AngII, which barely couples to Gq. (B) S1I8 has partial activity toward both the Gq-mediated and β-arrestin-mediated pathways. S1A2I8, which was designed to increase Gq signaling relative to S1I8 by favoring outward motion of TM6 in the binding pocket, shows increased Gq efficacy without any corresponding increase in β-arrestin efficacy. S1A2I8 is the R2A mutant of S1I8. Error bars represent standard error from 3–4 independent experiments. See also Table S2.

Decreasing the size of the C-terminal AngII residue is known to result in arrestin bias, but our simulations indicate that the conformation of the C-terminal peptide residue—not just its size—is a key determinant for bias. We predicted that a variant of AngII with the C-terminal aromatic ring constrained in a vertical orientation would favor the alternative intracellular conformation, leading to arrestin bias. We thus prepared an AngII analog with a 2-aminoindan-2-carboxylic acid substitution at F8 (Ind8-AngII, Fig 5A). Ind8-AngII is structurally identical to AngII except that the C-terminal phenyl moiety is tied back to the Cα atom by the addition of a single connecting methylene group. Our simulations show that this modification restricts the phenyl ring to remain vertical. Indeed, experimental characterization of Ind8-AngII shows that it is strongly arrestin-biased despite having a C-terminal residue even larger than that of AngII and the Gq-biased ligands (Fig. 5A, Table S2).

Based on our finding that outward motion of TM6 near the binding pocket is associated with the increased Gq signaling of Gq-biased ligands, we hypothesized that an alanine substitution at R2 would recover Gq activity for the partial agonist S1I8, which lacks a C-terminal phenylalanine but has another relatively large residue, isoleucine, as this position. Indeed, mutating R2 of S1I8 to alanine increases Gq activity without increasing β-arrestin activity (Fig. 5B, Table S2).

Discussion

To what extent does the molecular mechanism of biased signaling that we have identified for AT1R generalize to other GPCRs? Several lines of evidence suggest that similar intracellular conformations may be involved in biased signaling at other GPCRs. The key residues on the intracellular side of the receptor are highly conserved (32), with R3.50 found in 95% of class-A GPCRs and Y7.53 in 89%. Studies of the β2ΑR and 5-HT2BR (3, 26, 29, 33) have suggested that arrestin-biased ligands modulate the conformation of TM7, albeit without capturing the specific signaling conformations leading to bias or identifying how ligands select among these conformations. The R3.50 and Y7.53 rotamers associated with the canonical active and alternative AT1R conformations have been observed in experimental structures and simulations of other GPCRs (25–30, 34–36). Residues near the binding pocket are much less conserved across GPCRs, however, suggesting that the specific interactions ligands form to stabilize different intracellular conformations will vary substantially among receptors.

Other intracellular conformations likely also play a role in biased signaling at certain GPCRs. The canonical active and alternative conformations, which both appear to allow arrestin coupling, are sufficient to explain how bias arises at AT1R, where all known agonists substantially promote arrestin recruitment despite a great deal of variation in G-protein stimulation. At GPCRs such as the μ-opioid receptor (μOR), however, ligands have been identified that essentially eliminate arrestin signaling while stimulating G-protein signaling (37, 38). This suggests the existence of one or more conformations that couple effectively to G proteins but not arrestins.

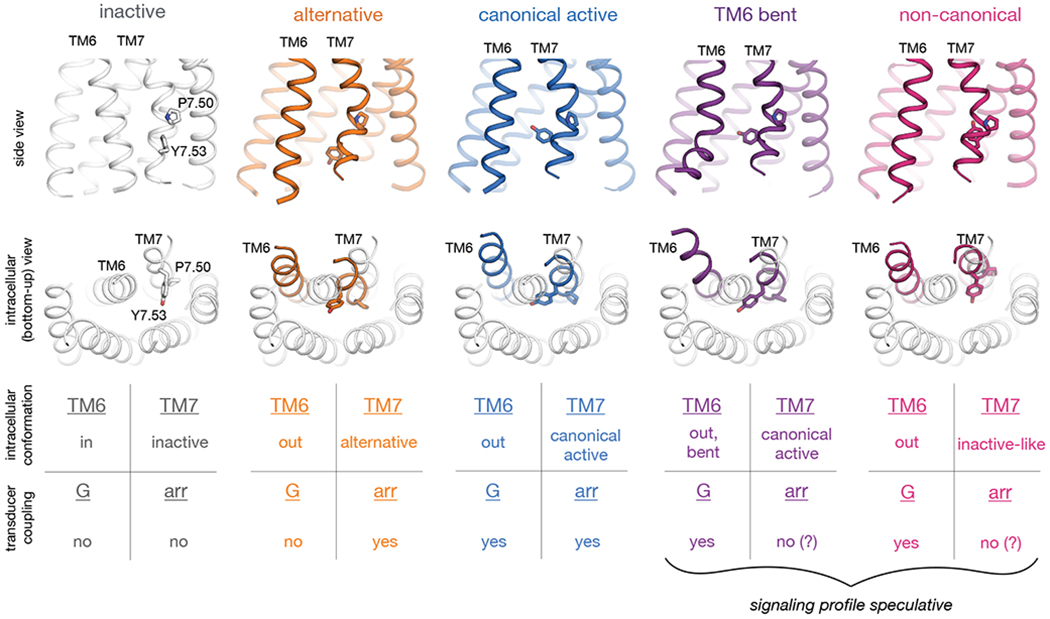

Our AT1R simulations suggest two candidate conformations. First, we observed a conformation in which the intracellular end of TM6 moves even farther away (4–5 Å) from the center of the helical bundle while TM7 remains in its canonical active conformation, resulting in an intracellular conformation that closely resembles Gs-bound class-A GPCR structures (5, 6, 39) (Fig. 6, Fig. S9). The larger intracellular cavity in this “TM6-bent” conformation might hinder efficient β-arrestin coupling by reducing the ability of the arrestin finger loop to pack favorably against the intracellular surface of the receptor (40). Second, TM7 sometimes adopts an inactive-like conformation, with the NPxxY motif shifted farther away from the helical bundle, while the intracellular end of TM6 remains in the outward position of the canonical active and alternative conformations (Fig. 6). This “non-canonical” intracellular conformation, which has been observed in a Gi-bound neurotensin receptor structure (41) and in β2AR simulations (31), also has a larger intracellular cavity than the canonical active conformation and could thus hinder efficient β-arrestin coupling.

Fig. 6. Observed intracellular conformations of AT1R.

Simulations indicate that AT1R adopts at least five distinct conformations that differ substantially in the intracellular positions of TM6 and TM7 and may have distinct cellular signaling profiles. In the inactive conformation (gray; illustrated by crystal structure (24)), TM6 occludes the transducer-binding pocket, hindering coupling to either G proteins or arrestins. The remaining four conformations all exhibit more outward positions of TM6 but differ substantially in the conformation of TM7, as illustrated by representative frames from our AT1R simulations. In the middle row, we show TMs 6 and 7 of these four conformations (colors) overlaid on all TMs of the inactive structure (gray). Our results suggest that in the alternative conformation (orange), the intracellular surface hinders coupling to G proteins but allows for arrestin coupling, whereas the canonical active conformation (blue) couples to both G proteins and arrestins. Two other conformations that AT1R adopts in simulation—the TM6-bent and non-canonical conformations, in purple and pink, respectively—have been observed in G-protein-bound structures of other GPCRs but might hinder arrestin coupling by increasing the volume of the transducer-binding pocket, preventing the arrestin finger loop from packing tightly against this pocket.

We note that a counterclockwise twist (seen from the extracellular side) of TM7 above its proline kink favors the alternative conformation—which couples preferentially to arrestins—while a clockwise twist favors the canonical active, TM6-bent, and non-canonical conformations, all of which couple effectively to G proteins. Modulating the orientation of TM7 might thus represent a general strategy for developing biased ligands.

The intracellular conformations we have identified may also confer signaling bias by affecting coupling to GPCR kinases (GRKs) (42). In particular, each of these conformations might promote or hinder GRK-mediated receptor phosphorylation, thus favoring or disfavoring arrestin coupling, respectively.

At AT1R, abolishing arrestin signaling while promoting G-protein signaling has proven more difficult than abolishing G-protein signaling while promoting arrestin signaling. Why is the reverse true at certain other GPCRs, such as μOR? First, sequence differences between GPCRs likely stabilize different signaling conformations. For example, as discussed in the companion manuscript (19), most class-A GPCRs have a serine at position 7.46, which forms a key part of the sodium-binding site. In the same position, AT1R has an asparagine (N7.46), which not only prevents sodium binding but also stabilizes the alternative conformation by forming polar contacts with TM3. Second, propensity to achieve particular signaling profiles may depend on the specific G proteins and arrestins to which a GPCR couples. For example, at the position on the α5 helix where Gq and Gs have a tyrosine that clashes with the downward R3.50 rotamer in AT1R’s alternative conformation, Gi and Go have a smaller cysteine residue. This cysteine could avoid severe clashes with the downward R3.50 rotamer in some (but not all) of the α5 helix orientations observed in GPCR–Gi/o complexes (Fig. S10), so the alternative conformation would likely disfavor Gi/o coupling less than Gq or Gs coupling. This may contribute to the difficulty of eliminating G protein signaling at μOR, whose cognate G protein is Gi. Indeed, a recent study indicates that, at AT1R, arrestin-biased ligands reduce Gq coupling more than Gi coupling (43).

Our results provide a detailed mechanism for biased signaling at AT1R, allowing the rational design of biased ligands. Our findings also suggest a general framework for achieving bias at other GPCRs, but further work will be necessary to elucidate detailed mechanisms of bias at these receptors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Betty Ha, Jason Wang, Joseph Paggi, and all members of the Dror lab for assistance with MD simulations, and Daniel Arlow for insightful comments.

Funding: Funding was provided by the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (C.-M.S), the Human Frontier Science Program (LT000916/2018-L) (C.-M.S), a Stanford Bio-X Bowes Fellowship (S.E.), the Vallee Foundation (A.C.K.), the Smith Family Foundation (A.C.K.), and National Institutes of Health grants R01GM127359 (R.O.D.), R01HL16037 (R.J.L.), and DP5OD021345 (A.C.K.). A.L.W.K. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Medical Research Fellow. R.J.L. is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This research used resources of the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility supported under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725.

Footnotes

Competing interests: R.J.L. is a founder and stockholder of Trevena and a director of Lexicon Pharmaceuticals. A.C.K. is an advisor for the Institute for Protein Innovation, a non-profit research institute.

Data and materials availability: Analysis code and data have been deposited at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3629830).

Supplementary materials:

References and notes

- 1.Santos R et al. , A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16, 19–34 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan L, Yan W, McCorvy JD, Cheng J, Biased Ligands of G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs): Structure–Functional Selectivity Relationships (SFSRs) and Therapeutic Potential. J. Med. Chem 61, 9841–9878 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu JJ, Horst R, Katritch V, Stevens RC, Wüthrich K, Biased signaling pathways in β2-adrenergic receptor characterized by 19F-NMR. Science 335, 1106–1110 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wingler LM et al. , Angiotensin analogs with divergent bias stabilize distinct receptor conformations. Cell 176, 468–478. e411 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen SG et al. , Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor–Gs protein complex. Nature 477, 549–555 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Nafría J, Lee Y, Bai X, Carpenter B, Tate CG, Cryo-EM structure of the adenosine A2A receptor coupled to an engineered heterotrimeric G protein. Elife 7, e35946 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koehl A et al. , Structure of the μ-opioid receptor–Gi protein complex. Nature 558, 547–552 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glukhova A et al. , Rules of engagement: GPCRs and G proteins. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci 1, 73–83 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda S, Qu Q, Robertson MJ, Skiniotis G, Kobilka BK, Structures of the M1 and M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor/G-protein complexes. Science 364, 552–557 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang Y et al. , Crystal structure of rhodopsin bound to arrestin by femtosecond X-ray laser. Nature 523, 561–567 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou XE et al. , Identification of phosphorylation codes for arrestin recruitment by G protein-coupled receptors. Cell 170, 457–469. e413 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin W et al. , A complex structure of arrestin-2 bound to a G protein-coupled receptor. Cell Res 29, 971–983 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajagopal S et al. , Quantifying ligand bias at seven-transmembrane receptors. Mol. Pharmacol 80, 367–377 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strachan RT et al. , Divergent transducer-specific molecular efficacies generate biased agonism at a G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR). J. Biol. Chem 289, 14211–14224 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabana J et al. , Identification of Distinct Conformations of the Angiotensin-II Type 1 Receptor Associated with the Gq/11 Protein Pathway and the β-Arrestin Pathway Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Biol. Chem 290, 15835–158354 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Violin JD et al. , Selectively engaging β-arrestins at the angiotensin II type 1 receptor reduces blood pressure and increases cardiac performance. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 335, 572–579 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeWire SM, Violin JD, Biased ligands for better cardiovascular drugs: dissecting G-protein-coupled receptor pharmacology. Circ. Res 109, 205–216 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryba DM et al. , Long-term biased β-arrestin signaling improves cardiac structure and function in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 135, 1056–1070 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wingler LM et al. , Angiotensin II and biased analogs induce structurally distinct active conformations within a GPCR. (companion paper). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wingler LM, McMahon C, Staus DP, Lefkowitz RJ, Kruse AC, Distinctive activation mechanism for angiotensin receptor revealed by a synthetic nanobody. Cell 176, 479–490. e412 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asada H et al. , Crystal structure of the human angiotensin II type 2 receptor bound to an angiotensin II analog. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 25, 570–576 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H, in Methods Neurosci (Elsevier, 1995), vol. 25, chap. 19, pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weis WI, Kobilka BK, The Molecular Basis of G Protein–Coupled Receptor Activation. Annu. Rev. Biochem 87, 897–919 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H et al. , Structure of the angiotensin receptor revealed by serial femtosecond crystallography. Cell 161, 833–844 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu F et al. , Structure of an Agonist-Bound Human A2A Adenosine Receptor. Science 332, 322–327 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wacker D et al. , Structural features for functional selectivity at serotonin receptors. Science 340, 615–619 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W et al. , Serial femtosecond crystallography of G protein–coupled receptors. Science 342, 1521–1524 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wacker D et al. , Crystal structure of an LSD-bound human serotonin receptor. Cell 168, 377–389. e312 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCorvy JD et al. , Structural determinants of 5-HT2B receptor activation and biased agonism. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol 25, 787 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lebon G et al. , Agonist-bound adenosine A2A receptor structures reveal common features of GPCR activation. Nature 474, 521 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dror RO et al. , Activation mechanism of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108, 18684–18689 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkatakrishnan AJ et al. , Diverse activation pathways in class A GPCRs converge near the G-protein-coupling region. Nature 536, 484–487 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Latorraca NR, Venkatakrishnan A, Dror RO, GPCR dynamics: structures in motion. Chem. Rev 117, 139–155 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan S, Filipek S, Palczewski K, Vogel H, Activation of G-protein-coupled receptors correlates with the formation of a continuous internal water pathway. Nat. Commun 5, 4733 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor BC, Lee CT, Amaro RE, Structural basis for ligand modulation of the CCR2 conformational landscape. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 116, 8131–8136 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nygaard R et al. , The dynamic process of β2-adrenergic receptor activation. Cell 152, 532–542 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manglik A et al. , Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature 537, 185 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmid CL et al. , Bias factor and therapeutic window correlate to predict safer opioid analgesics. Cell 171, 1165–1175. e1113 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carpenter B, Nehmé R, Warne T, Leslie AGW, Tate CG, Structure of the adenosine A2A receptor bound to an engineered G protein. Nature 536, 104 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saleh N, Saladino G, Gervasio FL, Clark T, Investigating allosteric effects on the functional dynamics of β2-adrenergic ternary complexes with enhanced-sampling simulations. Chem. Sci 8, 4019–4026 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato HE et al. , Conformational transitions of a neurotensin receptor 1–Gi1 complex. Nature 572, 80–85 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi M et al. , G protein–coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) orchestrate biased agonism at the β2-adrenergic receptor. Sci. Signal 11, eaar7084 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Namkung Y et al. , Functional selectivity profiling of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor using pathway-wide BRET signaling sensors. Sci. Signal 11, eaat1631 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobson MP, Friesner RA, Xiang Z, Honig B, On the role of the crystal environment in determining protein side-chain conformations. J. Mol. Biol 320, 597–608 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacobson MP et al. , A hierarchical approach to all‐atom protein loop prediction. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform 55, 351–367 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghanouni P et al. , The Effect of pH on β2 Adrenoceptor Function. J. Biol. Chem 275, 3121–3127 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ranganathan A, Dror RO, Carlsson J, Insights into the role of Asp792.50 in β2 adrenergic receptor activation from molecular dynamics simulations. Biochemistry 53, 7283–7296 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lomize MA, Lomize AL, Pogozheva ID, Mosberg HI, OPM: orientations of proteins in membranes database. Bioinformatics 22, 623–625 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Betz R, Dabble (v2.6.3). Zenodo 10.5281/zenodo.836914. (2017, August 1). [DOI]

- 50.Latorraca NR et al. , Molecular mechanism of GPCR-mediated arrestin activation. Nature 557, 452–456 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fahmy K et al. , Protonation states of membrane-embedded carboxylic acid groups in rhodopsin and metarhodopsin II: a Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy study of site-directed mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 90, 10206–10210 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahalingam M, Martínez-Mayorga K, Brown MF, Vogel R, Two protonation switches control rhodopsin activation in membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 105, 17795–17800 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hopkins CW, Le Grand S, Walker RC, Roitberg AE, Long-time-step molecular dynamics through hydrogen mass repartitioning. J. Chem. Theory Comput 11, 1864–1874 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryckaert J-P, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJ, Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comp. Phys 23, 327–341 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beglov D, Roux B, Finite representation of an infinite bulk system: solvent boundary potential for computer simulations. J. Chem. Phys 100, 9050–9063 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang J et al. , CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 14, 71–73 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klauda JB et al. , Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 7830–7843 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Best RB et al. , Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone ϕ, ψ and side-chain χ1 and χ2 dihedral angles. J. Chem. Theory Comput 8, 3257–3273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang J, MacKerell AD Jr, CHARMM36 all‐atom additive protein force field: Validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comp. Chem 34, 2135–2145 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Case DA et al. , AMBER 2017 (University of California, San Francisco, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pearlman DA et al. , AMBER, a package of computer programs for applying molecular mechanics, normal mode analysis, molecular dynamics and free energy calculations to simulate the structural and energetic properties of molecules. Comput. Phys. Commun 91, 1–41 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salomon-Ferrer R, Götz AW, Poole D, Le Grand S, Walker RC, Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 2. Explicit solvent particle mesh Ewald. J. Chem. Theory Comput 9, 3878–3888 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Case DA et al. , AMBER 2018 (University of California, San Francisco, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Case DA et al. , AMBER 2015 (University of California, San Francisco, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Case DA et al. , AMBER 2016 (University of California, San Francisco, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hukushima K, Nemoto K, Exchange Monte Carlo method and application to spin glass simulations. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 65, 1604–1608 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patriksson A, van der Spoel D, A temperature predictor for parallel tempering simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 10, 2073–2077 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Roe DR, Cheatham III TE, PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput 9, 3084–3095 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K, VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph 14, 33–38 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pándy-Szekeres G et al. , GPCRdb in 2018: adding GPCR structure models and ligands. Nucleic Acids Res 46, D440–D446 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Staus DP et al. , Sortase ligation enables homogeneous GPCR phosphorylation to reveal diversity in β-arrestin coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, 3834–3839 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Türker RK, Hall MM, Yamamoto M, Sweet CS, Bumpus FM, A New, Long-Lasting Competitive Inhibitor of Angiotensin. Science 177, 1203–1205 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Domazet I et al. , Characterization of Angiotensin II Molecular Determinants Involved in AT1 Receptor Functional Selectivity. Mol. Pharmacol 87, 982–995 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miura S-I, Karnik SS, Angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors bind angiotensin II through different types of epitope recognition. J. Hypertens 17, 397–404 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.