Abstract

Background:

The arteriovenous fistula (AVF) is central to haemodialysis treatment, but up to half of surgically created AVF fail to mature. Chronic kidney disease often leads to mineral metabolism disturbances that may interfere with AVF maturation through adverse vascular effects. This study tested associations between mineral metabolism markers and vein histology at AVF creation and unassisted and overall clinical AVF maturation.

Methods:

Concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 23, parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D metabolites: 1,25(OH)2D, 24,25(OH)2D, 25(OH)D, and bioavailable 25(OH)D were measured in pre-operative serum samples from 562 of 602 participants in the Haemodialysis Fistula Maturation Study, a multicentre, prospective cohort study of patients undergoing surgical creation of an autologous upper extremity AVF. Unassisted and overall AVF maturation were ascertained for 540 and 527 participants, respectively, within nine months of surgery or four weeks of dialysis initiation. Study personnel obtained vein segments adjacent to the portion of the vein used for anastomosis, which were processed, embedded, and stained for measurement of neointimal hyperplasia, calcification, and collagen deposition in the medial wall.

Results:

Participants in this substudy were 71% male, 43% black, and had a mean age of 55 years. Failure to achieve AVF maturation without assistance occurred in 288 (53%) participants for whom this outcome was determined. In demographic and further adjusted models, mineral metabolism markers were not significantly associated with vein histology characteristics, unassisted AVF maturation failure, or overall maturation failure, other than a biologically unexplained association of higher 24,25(OH)2D with overall failure. This exception aside, associations were non-significant for continuous and categorical analyses and relevant subgroups.

Conclusions:

Serum concentrations of measured mineral metabolites were not substantially associated with major histological characteristics of veins in patients undergoing AVF creation surgery, or with AVF maturation failure, suggesting that efforts to improve AVF maturation rates should increase attention to other processes such as vein mechanics, anatomy, and cellular metabolism among end stage renal disease patients.

Keywords: Vitamin D, Mineral metabolism, Chronic kidney disease, Haemodialysis, Vein histology, Arteriovenous fistula

INTRODUCTION

The arteriovenous fistula (AVF) is central for providing life sustaining haemodialysis treatments for end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients.1,2 Created by surgical anastomosis of a feeding artery and a draining vein, AVFs require subsequent maturation through a series of biological steps that include vasodilation, suppression of neointimal hyperplasia, outward remodelling, and expansion of the vessel lumen. However, up to half of all surgically created AVFs fail to achieve maturation and no therapies meaningfully improve AVF maturation outcomes.3,4

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) leads to interrelated disturbances in mineral and bone metabolism, termed chronic kidney disease mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD), which may perturb the orderly vascular remodelling process required for AVF maturation. For example, deficiency of calcitriol, the activated form of vitamin D, stimulates proinflammatory and pro-thrombotic cytokines and activates the renin angiotensin system.5,6 Genetic ablation of the vitamin D receptor in animal models stimulates renin expression with subsequent synthesis of angiotensin and aldosterone.7 Phosphate excess transforms arterial smooth muscle tissue into osteoblast-like cells, promoting calcification and arterial stiffness.8 Parathyroid hormone (PTH) stimulates renin release, raises intracellular calcium, and is associated with reduced vessel capacitance.9,10

It was hypothesised that mineral metabolism disturbances of CKD are associated with AVF maturation failure. To test this hypothesis, serum concentrations of four vitamin D metabolites plus fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), PTH, calcium, and phosphate were measured in 562 participants undergoing AVF creation surgery in a dedicated prospective study. Associations of individual vitamin D markers were evaluated with a) unassisted AVF maturation failure, b) overall AVF maturation failure, and c) histological characteristics of a segment of vein immediately adjacent to the portion used for fistula anastomosis creation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The Haemodialysis Fistula Maturation (HFM) Study enrolled 602 women and men with ESRD who underwent single stage surgical creation of an autologous upper extremity AVF for maintenance haemodialysis from March 2010 to September 2014 at any of seven university affiliated vascular access referral centres in the United States.11 All participants were followed prospectively to determine whether their AVF matured. Approximately 65% of participants were receiving maintenance dialysis at the time of enrolment with the remainder anticipated to start dialysis within three months of surgery. Patients were excluded from participation if they were ≥ 80 years old and not yet receiving maintenance dialysis, or if they had an anticipated life expectancy of < 9 months. All participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by institutional review boards at each site and the principles delineated in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed.

A total of 562 HFM Study participants (93.4%) provided a baseline blood sample for analysis of vitamin D and mineral metabolism markers. For the intermediate outcome of vein histology, vein sample cross sections judged sufficiently complete for assessment of the presence of calcification were available in 519 participants (86.2%), for ordinal grading of collagen deposition in 403 participants (66.9%), and for quantitative assessment of neointimal hyperplasia (NIH) in 345 (57.5%).

Mineral metabolite measurements

Blood specimens were obtained by HFM Study coordinators after overnight fasting within 0–221 (median 6, IQR 2–12, 90th percentile 26) days prior to surgical AVF creation and were stored at −80 °C. All specimens were first use (no previous freeze thaw). Immuno-affinity enrichment liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was used to quantify circulating concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D2, 1,25(OH)2D3, 24,25(OH)2D3, 25(OH)D2, 25(OH) D3.12,13 Trypsin digestion LC-MS/MS was used to quantify Trypsin digestion LC-MS/MS was used to quantify vitamin D binding globulin (DBG) and identify DBP isoforms.14 Specimens were thawed, alkalised with sodium hydroxide, covered, vortexed, and incubated at room temperature. Inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) for vitamin D metabolites ranged from 3.5% to 10.4% at high and low measured concentrations. Total serum 1,25(OH)2D was calculated as: 1,25(OH)2D2 + 1,25(OH)2D3 and total serum 25(OH)D as: 25(OH)D2 + 25(OH)D3. Bioavailable 25(OH)D was calculated as previously reported.15 Serum FGF-23 concentrations were measured using the Kainos immunoassay (singlicate inter-assay CV between 6.7% and 12.4%).16 Serum intact PTH concentrations were measured using an automated two site immunoassay (Beckmane Coulter, Inc., Brea, USA; inter-assay CV between 3.4% and 6.1%). Serum calcium concentrations were measured by indirect ion selective electrode and serum phosphate concentrations were measured using a timed rate colorimetry reaction.

Measurement of AVF maturation outcomes

The HFM Study outcome definition of unassisted AVF maturation was clinical use of the AVF with two needles for 75% of dialysis sessions within a four week period and either a mean dialysis machine blood pump speed of ≥ 300 mL/min over four consecutive sessions or, if that was not obtained, a measured spKt/V ≥ 1.4 or a urea reduction ratio (URR) > 70%. The first of the four qualifying sessions with pump speed ≥ 300 mL/min, or the date of the qualifying spKt/V or URR, had to occur by either nine months after AVF creation surgery or four weeks after dialysis initiation. The secondary outcome of overall AVF maturation (assisted or unassisted) was also evaluated. This outcome employed the same criteria but also allowed for endovascular or surgical interventions to aid in fistula maturation.

Determination of vein histology

A segment of vein immediately adjacent to that portion used for fistula anastomosis creation was surgically removed at the time of AVF creation, placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin followed by 70% ethanol after 24–72 hours, and shipped to the HFM Study Histology Core laboratory as previously described.11,17 Tissue was processed and embedded in paraffin following standard protocols. Four micron sections were placed onto slides and stained with Alizarin red S for calcium assessment and Movat’s pentachrome procedure for morphometry. Movat’s pentachrome procedure sharply defines key vein structures including collagen, nuclei, muscle, and fibrin, distinguishing in a single section the three histological layers (intima, media, adventitia) comprising the vein wall (Fig. S1).17 These staining features allowed definition of the vein lumen and space occupied by any NIH and localisation of pathological alterations such as accumulations of calcium or collagen (Fig. S2). Slides were photo-graphed at 40X and imported into ImagePro Plus software for analysis.

The HFM Study Histology Core quantified NIH as the percentage of the lumen area on one vein cross section slide occupied by NIH, scored the amount of collagen in the medial and internal elastic lamina (IEL) layers of the vein into one of the following categories: none, 1–25%, 26–50%, or 50–75%; and classified venous calcification in the intima and/or media as present in both layers, present in one, or absent. NIH quantification was restricted to fully circumferential cross sectional vein slices, which were available for 345 patients. Because only four participants had calcification in both the intima and media, calcium was defined as present vs. absent.

Other data collection

HFM Study coordinators assessed participant demographics, past medical histories, and social habits using standardised questionnaires and by abstracting relevant information from participants’ medical chart and pharmacy records. At baseline, height and weight were directly measured and vascular laboratory technicians measured blood pressure three times in the non-access arm. Serum concentrations of albumin, creatinine, and C-reactive protein were measured at the University of Washington Kidney Research Institute using the Beckman–Coulter DXC automated chemistry platform.

Statistical analyses

A previously validated cosinor model for periodic data was used to estimate the mean annual 25(OH)D concentration based on measured total 25(OH)D concentrations and the season of the year.18

Loglinear Poisson regression models with robust standard error estimates were used to estimate the relative risks of AVF maturation failure associated with specified increments or multiples of each mineral metabolism marker, after adjustment for potential confounding characteristics.19,20 A minimally adjusted model controlled for age, gender, and race. A second model added history of diabetes; body mass index (BMI); systolic blood pressure; smoking; education; maintenance dialysis status on HFM Study enrolment; and the use of oral calcitriol, paricalcitol, and vitamin D supplements (cholecalciferol or ergocalciferol). Models of AVF outcomes also adjusted for use of phosphate binders. Multiple imputation with 10 imputations and chained equations were used to account for missingness in unassisted AVF maturation (n = 22), overall AVF maturation (n = 35), race (n = 8), smoking (n = 4), and education (n = 15).21 Resulting estimates were combined using Rubin’s rules to account for variability in the imputation procedure.22 To screen for pronounced non-linearity, comparable but simplified models were fit in which each mineral metabolism marker was collapsed to tertiles or groups based on conventional cutpoints.23 Effect modification was also examined by age (≤ 55 vs. > 55), sex, race (black or other), dialysis (chronic vs. pre-dialysis at AVF creation surgery), and AVF location (forearm or upper arm).

We used multiple linear regression models to assess associations of vitamin D metabolites with NIH, analogous ordinal regression models to assess their associations with the amount of venous medial and IEL collagen, and logistic regression models to assess their associations with vein calcification, in each case adjusting for the covariable sets described above. As above, models were fit treating the mineral metabolism markers as continuous predictors or, alternatively, as categories using the likelihood ratio test to compare groups. The amount of missing covariable data was small (n = 14 cases), and missing or incomplete cross section vein samples were most likely due to completely random technical surgical or processing issues; therefore complete case analyses were used for histology analyses.

Analyses were performed using SAS v 9.4 University Edition and R v 3.2.3.

RESULTS

Study population

Among the 562 HFM Study participants included in this substudy, the mean age was 55 years, 70% were male, 43% were black, and 60% had a prior history of diabetes. Fistulas were created in the upper arms of 70% of participants. The participants in this substudy were qualitatively similar to the entire cohort. Failure to achieve AVF maturation without a surgical or endovascular intervention (unassisted maturation) occurred in 53% of the 540 participants who had this outcome observed, while overall maturation failure occurred in 29% of the 527 participants for whom this outcome was determined. Compared with participants with unassisted maturation success, those with unassisted maturation failure tended to be older, have a higher BMI, and were more likely to be female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 540 Haemodialysis Fistula Maturation Study participants

| Overall | Unassisted fistula maturation success (N = 252) | Unassisted fistula maturation failure (N = 288) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of consent, years | 55.0 ± 13.5 | 53.3 ± 13.9 | 56.2 ± 13.3 |

| Male | 398 (71) | 191 (76) | 189 (66) |

| Black race | 243 (44) | 105 (43) | 129 (45) |

| Prevalent cardiovascular disease | 270 (48) | 114 (45) | 143 (50) |

| History of diabetes | 337 (60) | 141 (56) | 182 (63) |

| Maintenance dialysis | 362 (64) | 167 (66) | 191 (66) |

| Education a | |||

| No high school diploma | 152 (28) | 77 (31) | 71 (25) |

| High school diploma | 152 (28) | 65 (26) | 79 (28) |

| Post-secondary education | 243 (44) | 104 (42) | 129 (46) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current smoker | 98 (18) | 46 (18) | 47 (16) |

| Former smoker | 201 (36) | 88 (35) | 105 (37) |

| Never smoked | 259 (46) | 115 (46) | 135 (47) |

| Fistula location | |||

| Forearm | 132 (23) | 52 (21) | 71 (25) |

| Upper arm | 430 (77) | 200 (79) | 217 (75) |

| Vein type | |||

| Forearm basilic vein | 10 (2) | 6 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Forearm cephalic vein | 122 (22) | 46 (18) | 68 (24) |

| Upper arm basilic vein | 153 (27) | 65 (26) | 82 (28) |

| Upper arm brachial vein | 9 (2) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Upper arm cephalic vein | 268 (48) | 132 (52) | 130 (45) |

| PWV: carotid-femoral, m/sb | 10.6 ± 3.2 | 10.5 ± 3.2 | 10.7 ± 3.1 |

| PWV: carotid-radial, m/sc | 8.8 ± 1.7 | 8.8 ± 1.7 | 8.8 ± 1.7 |

| Minimum pre-op draining vein diameterd | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.0 |

| Pre-op upper arm fistula feeding artery flowe | 56.5 (33.8–85.2) | 49.0 (28.4–82.5) | 62.4 (40.5–87.6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 30.4 ± 7.6 | 29.0 ± 7.2 | 31.4 ± 7.7 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 151.4 ± 23.8 | 151.8 ± 24.6 | 151.5 ± 23.1 |

| Statin use | 313 (56) | 134 (53) | 163 (57) |

| Oral calcitriol or hectorol use | 133 (24) | 61 (24) | 63 (22) |

| Cholecalciferol use | 101 (18) | 32 (13) | 64 (22) |

| Phosphate binder use | 329 (59) | 172 (68) | 149 (52) |

| C reactive protein, mg/L | 15.1 ± 28.2 | 13.0 ± 21.4 | 16.8 ± 31.7 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 10.5 ± 1.7 | 10.3 ± 1.6 | 10.6 ± 1.7 |

Unassisted fistula maturation outcomes directly observed for 540 of the 562 study participants. All values in table presented as mean ± standard deviation for continuous covariates or median (interquartile range) if substantially skewed, and N (%) for categorical covariates. PWV = pulse wave velocity.

n = 506.

n = 337.

n = 353.

n = 446.

n = 120.

Associations with unassisted fistula maturation

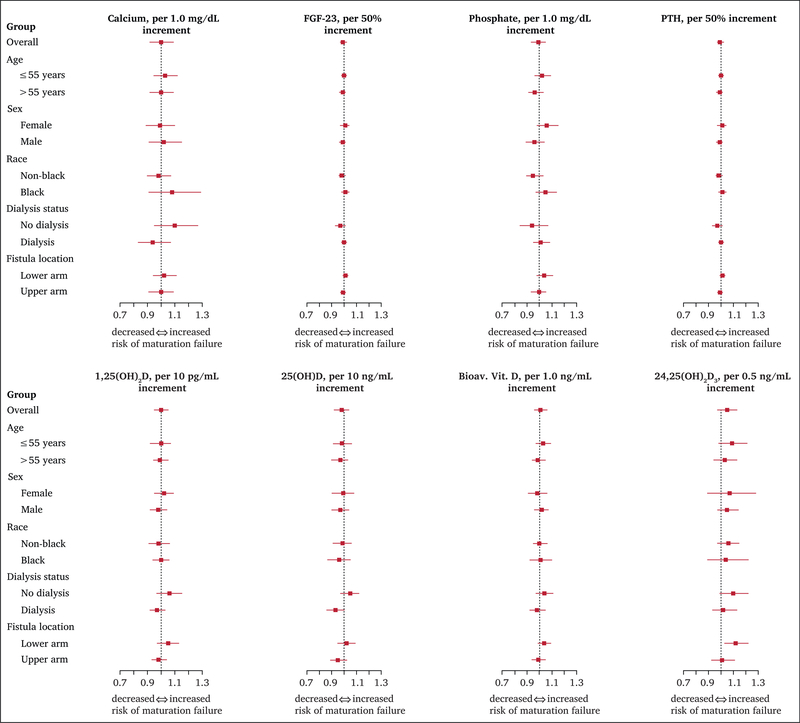

After basic adjustment for age, sex, race, and study site (Model 1), none of the mineral metabolism markers, assessed as continuous exposures, were associated with unassisted AVF maturation failure (Table 2). Similar non-significant associations were observed after further adjustment for BMI, dialysis status, diabetes, education, smoking, blood pressure, and medications (Model 2). Calcium and phosphate did not significantly interact in either model. There were also no significant associations between mineral metabolism markers using tertiles or clinically accepted cut points and unassisted AVF maturation failure. Associations between serum concentrations of mineral metabolism markers and unassisted AVF maturation failure outcomes were similar in size across categories of age, gender, race, fistula location, and dialysis status (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Associations between mineral metabolism markers and unassisted fistula maturation failure

| Mineral marker | Increment | Model 1a |

Model 2b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aRR (95% CI) | p value | aRR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 23 | Per 50% greater | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | .23 | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | .58 |

| Parathyroid hormone (PTH) | Per 50% greater | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | .69 | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | .61 |

| Calcium | Per 1.0 mg/dL greater | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | .99 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) | .98 |

| Phosphate | Per 1.0 mg/dL greater | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | .65 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | .70 |

| 1,25(OH)2D | Per 10 pg/mL greater | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | .98 | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | .92 |

| 25(OH)D | Per 10 ng/mL greater | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | .42 | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | .43 |

| Bioavailable 25(OH)D | Per 1.0 ng/mL greater | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | .85 | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | .75 |

| 24,25(OH)2D | Per 0.5 ng/mL greater | 1.05 (0.97–1.13) | .26 | 1.05 (0.97–1.13) | .26 |

Unassisted fistula maturation outcomes imputed for all 562 study participants. aRR = adjusted relative risk; FGF 23 = fibroblast growth factor 23; PTH = parathyroid hormone; aRR = adjusted relative risk; CI = confidence interval.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, black race, and study site.

Model 2 adds adjustment for body mass index, maintenance dialysis status, previous diabetes, education (less than high school/high school diploma/more than high school), systolic blood pressure, smoking status, and use of calcitriol, paricalcitol, vitamin D supplementation, and phosphate binders.

Figure 1.

Associations between continuous serum mineral metabolism concentrations and unassisted fistula maturation failure by subgroup. X axes show the adjusted relative risk of unassisted fistula maturation failure per unit increment in each mineral metabolism marker within subgroups. The solid squares represent estimated relative risks and the solid horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The dashed vertical line indicates the null association (relative risk of 1.0). All models adjusted for age, sex, black race, study site, body mass index, dialysis status, previous diabetes, education (less than high school/high school diploma/more than high school), systolic blood pressure, smoking status, and use of calcitriol, paricalcitol, vitamin D supplementation, and phosphate binders (Model 2). Missing unassisted fistula maturation outcomes were multiply imputed. Bioav. Vit. D = bioavailable vitamin D; FGF-23 = fibroblast growth factor-23; PTH = parathyroid hormone.

Associations with overall fistula maturation

Failure to achieve overall AVF maturation (with or without assistance) occurred in 29% of 527 participants who had this outcome resolved. Serum concentrations of FGF-23, PTH, phosphate, calcium, and all but one vitamin D metabolite, assessed continuously, were not significantly associated with overall AVF maturation failure in demographic adjusted or further adjusted models (Table S1). The sole exception was a 17% greater risk of overall AVF maturation failure per 0.5 ng/dL higher serum 24,25(OH)2D concentration in both the demographically and fully adjusted models (p = .01 for both models, 95% CI 4–30% greater after full adjustment). Analyses by tertiles also found this marker, but no other mineral metabolism markers, to be statistically significantly associated with overall maturation failure (p = .03 for both models, data not shown).

Associations with vein histology

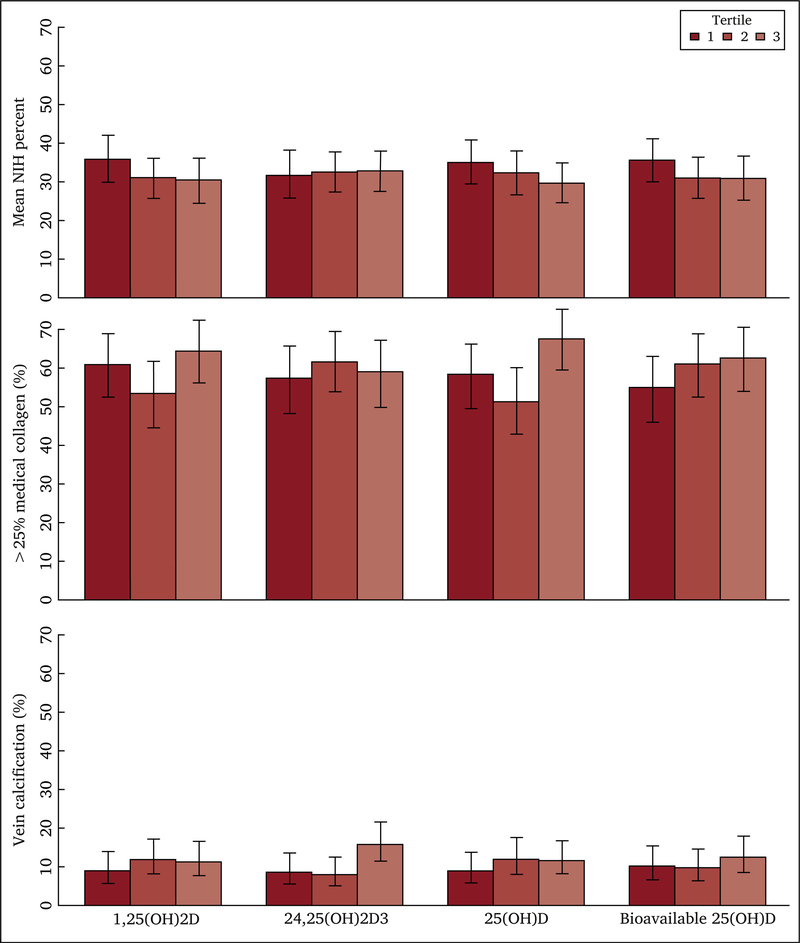

NIH was present in 88.1% of participants in the subcohort. The median proportion of the venous lumen staining for NIH was 25.3%. The proportions of participants classified as having no extra collagen, ≤ 25% collagen, 26–50% collagen, and 51–75% collagen in the medial layer of the vein were 2.7%, 39.7%, 49.9%, and 7.7%, respectively. Calcification was present in 11.8% of the venous segments. There were no statistically significant trends of mean NIH (Table 3), vein calcification (Table 4), or collagen deposition (Table 5, Table S2, Fig. 2) with tertiles of vitamin D metabolites. These results were not materially altered after basic adjustment for age, race, and gender (Model 1) or further adjustment for smoking, blood pressure, BMI, comorbidities, education, and vitamin D medications (Model 2). Analyses of vitamin D metabolites as continuous variables also revealed no significant associations with NIH in either basic or further adjusted models.

Table 3.

Adjusted associations between vitamin D biomarkers and venous neointimal hyperplasia

| Vitamin D metabolite | Tertile | Mean NIH % | Model 1a (n = 345) |

Model 2b (n = 336) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIH % diff (95% CI) | p value | NIH % diff (95% CI) | p value | ||||

| 1,25(OH)2D, pm/mL | >20.49 | 30.4 | Ref. | .22 | Ref. | .57 | |

| 8.48–20.49 | 30.8 | −0.2 (−7.67–7.27) | 0.44 (−7.27–8.15) | ||||

| <8.48 | 35.7 | 5.64 (−2.01–13.28) | 3.92 (−4.24–12.09) | ||||

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | >30 | 29.7 | Ref. | .28 | Ref. | .36 | |

| 20–30 | 32.2 | 2.41 (−5.14–9.97) | 4.35 (−3.68–12.38) | ||||

| <20 | 35 | 6 (−1.43–13.44) | 5.81 (−2.38–14.01) | ||||

| Bioavailable 25(OH)D, ng/mL |

>2.95 | 30.9 | Ref.c | .15 | Ref.d | .25 | |

| 1.67–2.95 | 31.1 | 1.59 (−5.98–9.14) | 1.75 (−6.01–9.50) | ||||

| <1.67 | 35.4 | 7.56 (−0.65–15.77) | 7.1 (−1.78–15.98) | ||||

| 24,25(OH)2D3, ng/mL | >0.44 | 32.7 | Ref. | .81 | Ref. | .72 | |

| 0.18–0.44 | 32.5 | 2.47 (−5.16–10.10) | 2.97 (−4.96–10.90) | ||||

| <0.18 | 31.8 | 1.01 (−7.32–9.33) | 0.66 (−7.94–9.26) | ||||

NIH = neointimal hyperplasia; diff = difference; CI = confidence interval.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, and black race.

Model 2 adds adjustment for body mass index, maintenance dialysis status, previous diabetes, education, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, and use of calcitriol, paricalcitol, and vitamin D supplementation.

n = 344 overall.

n = 335 overall.

Table 4.

Adjusted associations of vitamin D biomarkers with venous calcification (i.e. proportion with any calcification)

| Vitamin D metabolite | Tertile | Model 1a (n = 519) |

Model 2b (n = 505) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D, pm/mL | > 20.49 | Ref. | .91 | Ref. | .75 |

| 8.48–20.49 | 0.99 (0.52–1.92) | 0.87 (0.44–1.73) | |||

| < 8.48 | 0.87 (0.43–1.76) | 0.74 (0.35–1.60) | |||

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | > 30 | Ref. | .82 | Ref. | .70 |

| 20–30 | 1.21 (0.63–2.35) | 1 (0.50–2.02) | |||

| < 20 | 1.01 (0.51–2.03) | 0.75 (0.35–1.63) | |||

| Bioavailable 25(OH)D, ng/mL | > 2.95 | Ref.c | .40 | Ref.d | .48 |

| 1.67–2.95 | 1.02 (0.52–2.00) | 0.91 (0.45–1.83) | |||

| < 1.67 | 1.58 (0.76–3.29) | 1.42 (0.65–3.10) | |||

| 24,25(OH)2D3, ng/mL | > 0.44 | Ref. | .64 | Ref. | .43 |

| 0.18–0.44 | 0.72 (0.36–1.44) | 0.63 (0.31–1.30) | |||

| < 0.18 | 0.89 (0.43–1.83) | 0.89 (0.42–1.89) | |||

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, and black race.

Model 2 adds adjustment for body mass index, maintenance dialysis status, previous diabetes, education, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, and use of calcitriol, paricalcitol, and vitamin D supplementation.

n = 402 overall.

n = 390 overall.

Table 5.

Adjusted associations between vitamin D biomarkers and increasing collagen in medial muscle layer of the vein (i.e. proportion with > 25% medial collagen)

| Vitamin D metabolite | Tertile | Model 1a (n = 403) |

Model 2b (n = 391) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

| 1,25(OH)2D, pm/mL | > 20.49 | Ref. | .29 | Ref. | .30 |

| 8.48–20.49 | 0.71 (0.44–1.12) | 0.7 (0.43–1.13) | |||

| < 8.48 | 0.94 (0.58–1.51) | 0.91 (0.55–1.51) | |||

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | > 30 | Ref. | .17 | Ref. | .11 |

| 20–30 | 0.64 (0.40–1.03) | 0.58 (0.35–0.97) | |||

| < 20 | 0.78 (0.49e1.24) | 0.72 (0.43–1.20) | |||

| Bioavailable 25(OH)D, ng/mL | > 2.95 | Ref.c | .58 | Ref.d | .58 |

| 1.67–2.95 | 1.03 (0.64–1.66) | 1.06 (0.65–1.73) | |||

| < 1.67 | 0.81 (0.49–1.35) | 0.82 (0.47–1.42) | |||

| 24,25(OH)2D3, ng/mL | > 0.44 | Ref. | .50 | Ref. | .58 |

| 0.18–0.44 | 1.32 (0.82–2.14) | 1.28 (0.77–2.12) | |||

| < 0.18 | 1.11 (0.66–1.85) | 1.06 (0.62–1.80) | |||

OR = odds ratio from proportional odds ordinal models; CI = confidence interval.

Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, black race.

Model 2 adds adjustment for body mass index, maintenance dialysis status, previous diabetes, education, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, and use of calcitriol, paricalcitol, and vitamin D supplementation.

n = 517 overall.

n = 503 overall.

Figure 2.

Associations between tertiles of vitamin D metabolites and vein histology characteristics. X axes show serum vitamin D metabolite concentrations using tertiles (i.e., < 8.48, 8.48–20.49, and > 20.49 pm/mL for 1,25[OH]2D; < 1.67, 1.67–2.95, and > 2.95 ng/mL for bioavailable 25[OH]D; and < 0.18, 0.18–0.44, and > 0.44 for 24,25[OH]2D3), except for 25(OH) D concentrations for which established Endocrine Society Categories of <20, 20–30, and >30 ng/mL were used. Plots depict the mean percentage of neointimal hyperplasia in the vein, proportion with >25% medial collagen in the vein, and proportion with any vein calcification, with solid vertical bars representing the 95% confidence intervals. NIH = neointimal hyperplasia.

DISCUSSION

It was hypothesised that serological markers of CKD-MBD would be associated with AVF maturation failure and with histological attributes of vein segments obtained during AVF creation surgery. However, in this multisite prospective study of newly created AVFs, vitamin D metabolites were not associated with the amount of NIH, medial or IEL collagen, or the presence of calcification in the pre-surgical vein. Moreover, associations between serum concentrations of all but one mineral metabolism marker and unassisted and overall AVF maturation outcomes were modest and non-significant in continuous and categorical analyses, and similarly across clinically relevant subgroups. Although higher serum 24,25(OH)2D concentrations were associated with overall AVF maturation failure, this finding probably represents chance, because it was observed in the context of multiple comparisons, is in the opposite direction of that expected from biological knowledge, and is limited to only one CKD-MBD marker and an outcome that reflects selective clinical interventions as well as natural history. Taken as a whole, these findings do not support the hypothesised role for CKD-MBD in AVF maturation, and suggest that greater attention be directed toward other relevant biological pathways that may contribute to fistula outcomes.

It is, however, possible that the serological markers measured in this study inadequately captured the complex pathophysiological processes of CKD-MBD. For example, the loss of major calcification inhibitors, such as fetuin-A and matrix Gla protein, promotes osteogenic transformation and calcification of vascular smooth muscle tissue, which could impede normal vasodilatory processes within the vascular access.24,25 The activated form of vitamin D, 1,25(OH)2D, modulates transcription of genes within major inflammatory and thrombotic pathways.5,6 However, circulating concentrations of vitamin D metabolites may not reflect vitamin D activity within the cell.

A second possibility is that the impact of CKD-MBD on vascular function may be blunted in later stages of CKD. Nearly 90% of the ESRD participants in this study already had neointimal hyperplasia in their surgical vein segment, and > 97% had medial collagen deposition. Moreover, later stages of CKD amplify disturbances in circulating mineral metabolism markers via aberrant feedback mechanisms, potentially weakening associations between these markers and vascular outcomes. In studies of early CKD and the general population, higher circulating concentrations of PTH, FGF-23, and phosphate are associated with arterial stiffness, left ventricular hypertrophy, and vascular calcification.10,26,27

Finally, CKD-MBD may not play a meaningful role in AVF maturation. Successful fistula maturation requires an orderly vascular remodelling process, which includes nitric oxide mediated vasodilation, smooth muscle relaxation, elaboration of matrix metalloproteinases, digestion of the IEL, and local inhibition of platelet aggregation.28–31 Together these processes promote the substantial increases in blood flow and vessel diameter required for successful AVF maturation.32–34 Although mineral metabolism disturbances may contribute to underlying vessel stiffness, other physiological processes may predominate in facilitating vasodilation of the feeding artery and draining vein following surgical AVF creation.

This study has several strengths. Serum concentrations of mineral metabolism markers were measured using state of the art laboratory assays, including quantification of vitamin D metabolites by high performance liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy. Unassisted and overall AVF maturation outcomes were adjudicated within the largest prospective cohort study of AVF creation to date and vein histology was appraised by a highly experienced, centralised pathology centre. The study definition of AVF maturation was clinically relevant, easily ascertainable across study sites, and generally independent of differing practices between facilities thereby limiting potential inter-site variability. HFM Study participants were recruited from multiple geographic sites, minimizing the potential influence of specific surgical practices at a single centre and enhancing the generalizability of the study results. Nevertheless, the sample size was moderate, hence some associations may have been missed. Statistical analyses used Poisson models for maturation failure rates.19 These are more readily interpretable for frequent outcomes such as maturation failure, than more commonly used logistic regression models for maturation failure odds. Limitations of this study also include measurement of only a selected group of mineral metabolism markers and quantification of these markers at a single time point during late stage CKD. Quantitative assessment of NIH was confined to the < 60% of HFM Study patients with full circumference vein cross section samples, which could have introduced bias if related to AVF maturation. Additionally, information regarding exposures that may have led to the preponderance of NIH was not systematically collected by the HFM Study. However, neointimal lesions were similar in the more superficial upper arm cephalic veins to those in the upper arm basilic or brachial veins, which tend to be deeper and generally less accessible to standard venepuncture, implying a primary role for uraemia driven toxicity in the pathogenesis of these lesions.17

Current guidelines specify numerous factors that increase the risk of AVF maturation failure including older age, diabetes, and anatomical site of surgery.35 The present findings from a US multicentre cohort study of AVF creation demonstrate that mineral metabolism disturbances are highly prevalent among patients undergoing AVF surgery. However, despite plausible biological mechanisms by which mineral metabolism disturbances could interfere with the orderly process of AVF maturation, multiple serological measurements of mineral metabolism were not associated with differences in AVF maturation failure.

In conclusion, serum markers of CKD-MBD were not materially associated with AVF maturation outcomes in a contemporary study of AVF creation surgery and vitamin D metabolites were not materially associated with vein pathology at the time of AVF creation. This lack of positive findings could be because of the inability of the selected markers to reflect the underlying pathophysiological processes of CKD-MBD, or the singular assessment of these markers in advanced kidney disease. However, the lack of support in these data for the CKD-MBD hypothesis does diminish the plausibility of this pathway as a major driver of maturation failure, suggesting that other relevant biological pathways arising from CKD should be carefully explored for their impact on AVF maturation.

Supplementary Material

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

Patients with chronic kidney disease have disturbances of mineral metabolism, which may interfere with the vascular remodelling process required for successful maturation of arteriovenous fistulae. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study of end stage renal disease patients, either undergoing or anticipated to soon require maintenance haemodialysis, to assess relationships between serum mineral metabolites and abnormalities of vein segments used to create haemodialysis arteriovenous fistulas, and with fistula maturation. Although these veins exhibit distinct unusual features, the measured mineral metabolism markers were not materially associated with functional arteriovenous fistula maturation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients for their participation in the HFM Study. We acknowledge Lin Belt, Carl Abts, and Lauren Alexander for their invaluable expertise at the HFM Ultrasound Core.

FUNDING

The HFM Study is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants U01DK082179, U01DK082189, U01DK082218, U01DK082222, U01DK082232, U01DK082236, and U01DK082240. This ancillary study was funded by grant R01DK094891.

Footnotes

APPENDIX A. SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2019.01.022.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Kestenbaum reports receiving consulting fees from Sanofi Inc. No other authors report a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jindal K, Chan CT, Deziel C, Hirsch D, Soroka SD, Tonelli M, et al. Hemodialysis clinical practice guidelines for the Canadian Society of Nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17:S1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brescia MJ, Cimino JE, Appel K, Hurwich BJ. Chronic hemodialysis using venipuncture and a surgically created arteriovenous fistula. N Engl J Med 1966;275:1089–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dember LM, Beck GJ, Allon M, Delmez JA, Dixon BS, Greenberg A, et al. Effect of clopidogrel on early failure of arteriovenous fistulas for hemodialysis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:2164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon BS. Why don’t fistulas mature? Kidney Int 2006;70: 1413–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li YC, Kong J, Wei M, Chen ZF, Liu SQ, Cao LP. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 2002;110:229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oelzner P, Franke S, Muller A, Hein G, Stein G. Relationship between soluble markers of immune activation and bone turnover in postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 1999;38:841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassi E, Adamopoulos C, Basdra EK, Papavassiliou AG. Role of vitamin D in atherosclerosis. Circulation 2013;128:2517–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giachelli CM, Jono S, Shioi A, Nishizawa Y, Mori K, Morii H. Vascular calcification and inorganic phosphate. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;38:S34–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schluter KD, Piper HM. Trophic effects of catecholamines and parathyroid hormone on adult ventricular cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol 1992;263:H1739–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosworth C, Sachs MC, Duprez D, Hoofnagle AN, Ix JH, Jacobs DR Jr, et al. Parathyroid hormone and arterial dysfunction in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Clin Endocrinol 2013;79:429–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dember LM, Imrey PB, Beck GJ, Cheung AK, Himmelfarb J, Huber TS, et al. Objectives and design of the hemodialysis fistula maturation study. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;63:104–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strathmann FG, Laha TJ, Hoofnagle AN. Quantification of 1alpha, 25-dihydroxy vitamin D by immunoextraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem 2011;57: 1279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Boer IH, Sachs MC, Chonchol M, Himmelfarb J, Hoofnagle AN, Ix JH, et al. Estimated GFR and circulating 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 concentration: a participant-level analysis of 5 cohort studies and clinical trials. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64: 187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson CM, Lutsey PL, Misialek JR, Laha TJ, Selvin E, Eckfeldt JH, et al. Measurement by a novel LC-MS/MS methodology reveals similar serum concentrations of vitamin D-binding protein in blacks and whites. Clin Chem 2016;62:179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powe CE, Karumanchi SA, Thadhani R. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D in blacks and whites. N Engl J Med 2014;370:880–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imel EA, Peacock M, Pitukcheewanont P, Heller HJ, Ward LM, Shulman D, et al. Sensitivity of fibroblast growth factor 23 measurements in tumor-induced osteomalacia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:2055–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alpers C, Imrey P, Hudkins K. Histopathology of veins obtained at hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula creation surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;28:3076–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sachs MC, Shoben A, Levin GP, Robinson-Cohen C, Hoofnagle AN, Swords-Jenny N, et al. Estimating mean annual 25-hydrox-yvitamin D concentrations from single measurements: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:1243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter RE, Lipsitz SR, Tilley BC. Quasi-likelihood estimation for relative risk regression models. Biostatistics 2005;6:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. STATA J 2004;4:227–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:1911–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ketteler M, Bongartz P, Westenfeld R, Wildberger JE, Mahnken AH, Böhm R, et al. Association of low fetuin-A (AHSG) concentrations in serum with cardiovascular mortality in patients on dialysis: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2003;361:827–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moe SM, Reslerova M, Ketteler M, Wildberger JE, Mahnken AH, Böhm R, et al. Role of calcification inhibitors in the pathogenesis of vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease (CKD). Kidney Int 2005;67:2295e304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutierrez OM, Januzzi JL, Isakova T, Laliberte K, Smith K, Collerone G, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation 2009;119: 2545–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foley RN, Collins AJ, Herzog CA, Ishani A, Kalra PA. Serum phosphorus levels associate with coronary atherosclerosis in young adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss MF, Scivittaro V, Anderson JM. Oxidative stress and increased expression of growth factors in lesions of failed hemodialysis access. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;37:970–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy-Chaudhury P, Wang Y, Krishnamoorthy M, Zhang J, Banerjee R, Munda R, et al. Cellular phenotypes in human stenotic lesions from haemodialysis vascular access. Nephrol Dial Transpl 2009;24:2786–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rotmans JI, Velema E, Verhagen HJ, Blankensteijn JD, de Kleijn DP, Stroes ES, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces intimal hyperplasia in a porcine arteriovenous-graft model. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:432–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kokubo T, Ishikawa N, Uchida H, Chasnoff SE, Xie X, Mathew S, et al. CKD accelerates development of neointimal hyperplasia in arteriovenous fistulas. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;20: 1236–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Won T, Jang JW, Lee S, Han JJ, Park YS, Ahn JH. Effects of intraoperative blood flow on the early patency of radiocephalic fistulas. Ann Vasc Surg 2000;14:468–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seyahi N, Altiparmak MR, Tascilar K, Pekpak M, Serdengecti K, Erek E. Ultrasonographic maturation of native arteriovenous fistulae: a follow-up study. Ren Fail 2007;29:481–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robbin ML, Chamberlain NE, Lockhart ME, Gallichio MH, Young CJ, Deierhoi MH, et al. Hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula maturity: US evaluation. Radiology 2002;225:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidli J, Widmer MK, Basile C, de Donatoa G, Gallienia M, Gibbonsa CP, et al. Editor’s choice – vascular access: 2018 clinical practice guidelines of the European society For vascular surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2018;vol. 55:757–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.