Abstract

The pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV2 novel coronavirus is creating a global crisis. There is a global ambience of uncertainty and anxiety. In addition, nations have imposed strict and restrictive public health measures including lockdowns. In this heightened time of vulnerability, public cooperation to preventive measures depends on trust and confidence in the health system. Trust is the optimistic acceptance of the vulnerability in the belief that the health system has best intentions. On the other hand, confidence is assessed based on previous experiences with the health system. Trust and confidence in the health system motivate people to accept the public health interventions and cooperate with them. Building trust and confidence therefore becomes an ethical imperative. This article analyses the COVID-19 pandemic in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the state’s response to this pandemic. Further, it applies the Trust-Confidence-Cooperation framework of risk management to analyse the influence of public trust and confidence on the Tamil Nadu health system in the context of the preventive strategies adopted by the state. Finally, the article proposes a six-pronged strategy to build trust and confidence in health system functions to improve cooperation to pandemic containment measures.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV2, Pandemic, Public health, Trust, Confidence, Cooperation

Introduction

The SARS-CoV2 virus is spreading fast and has created a pandemic of far reaching consequences. As of 30 April 2020, there are 3.01 million confirmed cases globally with 0.2 million deaths due to COVID-19. In India, there are 31,332 confirmed cases with 1007 deaths (World Health Organization 2020). Several countries have instated strict restrictive measures to contain the spread of the respiratory virus. India has instilled one of the strictest lockdowns in history, of 1.3 billion people, currently counting more than 35 days (UN News 2020). This has led to a tremendous burden on people of all sections of the society, especially among the poor (Human Rights Watch 2020). The combination of fear due to the illness and restrictive public health measures putting people into difficulties has led to a heightened state of vulnerability.

In such situations of vulnerability, the relationship between the people and the health system is strongly dependent on trust. Trust is the optimistic feeling of acceptance of one’s vulnerability in the hope that the party who is trusted will act in one’s best interest (Hall et al. 2001). O’Neill describes demonstration of trustworthiness as the basis of trusting community-health system relationships. She argues that trust cannot be built by intention and effort (O’Neill 2002). A global pandemic is one of the greatest litmus tests of trust in a health system. Trust has both intrinsic and instrumental values during pandemic times. Having trust in the health system reassures people that the health system will take care of them and help them carry on with their lives. A high level of trust in the health system also fosters a sense of cooperation with the system in adopting all public health measures that are recommended by the system (Kehoe and Ponting 2003). Mistrust in the health system can be counterproductive in effective control of the infection (van der Weerd et al. 2011). This is particularly important when the public health measures are highly restrictive.

Therefore, public trust in the health system during pandemic times becomes an ethical imperative. This article will analyse the COVID-19 pandemic in the south Indian state of Tamil Nadu with a brief description of the measures adopted by the state, the role of trust and confidence in motivating the community to cooperate with the health system and potential strategies for building trust and confidence of people.

Health System Response to COVID-19 in Tamil Nadu, India

Tamil Nadu saw its first case of COVID-19 on 07 March 2020 (Josephine M. 2020). The state has implemented several important pandemic control measures. Firstly, a large number of international travellers who arrived in Tamil Nadu were placed on home quarantine and were followed up daily through telephone calls (Chandna 2020). Active contact tracing of all confirmed cases of COVID-19 was performed by the health care providers including all those who attended a religious conference in New Delhi and contracted the illness from the meeting (Trivedi 2020). Aggressive cluster containment activities are being implemented in which the containment zone and its perimeter are well described and health care workers go door to door conducting active surveillance of COVID-19 like symptoms (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare 2020). For the contact tracing and cluster containment, the state adopted the policy of ‘collective action of the entire government machinery’ meaning the health, revenue, police and other departments also engaged in these activities at the district level (Chandna 2020). The state has also initiated steps and is working hard to prepare isolation beds, intensive care unit beds and ventilators. In addition, the department of health and family welfare is active on social media and disseminates information, education and communication actively (Directorate of Public Health and Preventive Medicine 2020). In order to enable physical distancing between people, the state announced a stringent lockdown of all commercial, business, education and non-essential activities (The Hindu 2020).

The Trust-Confidence-Cooperation Model of Risk Management

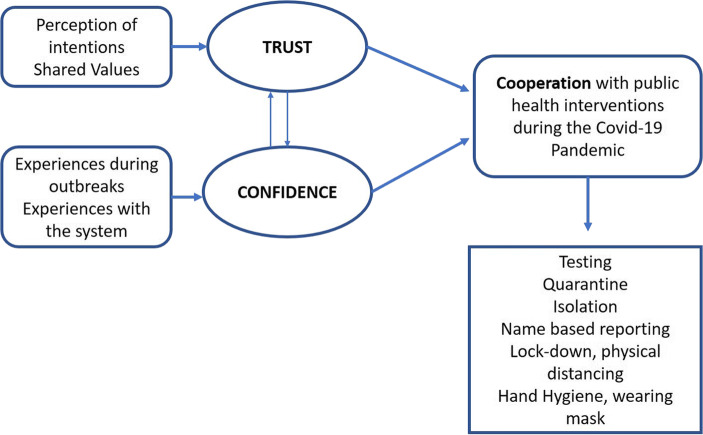

The Trust-Confidence-Cooperation model was developed by Earle, Siegrist and Gutscher to describe risk management in organizations (Earle et al. 2012). This model is based on the premise that the community must have trust and confidence in the state for it to cooperate with the public health control measures to contain COVID-19. The belief is that if the community perceives that the health system has their best interests in mind and its intentions are to protect the community, it develops trust. The past experiences with the health system during previous outbreaks and emergencies and overall experience of the people with the system builds confidence. It is the presence of this combination of value and intention-based trust and performance-based confidence that motivates people to cooperate with the various risk reduction and mitigation strategies, especially the restrictive ones (Earle 2010). This model is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The Trust-Confidence-Cooperation model showing trust based on intentions and values and confidence based on competence influence cooperation to the public health interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic

The model in Fig. 1 is used in the analysis that follows. The trust in the public health system is initially described. This is followed by an analysis of the public confidence in the health system during outbreaks based on past experiences and overall health system functioning. It is argued that trust and confidence in the health system are likely to influence the cooperation with public health interventions listed in the figure.

Public Trust in the Health System in Tamil Nadu

Trust in the health system in Tamil Nadu has been nourished over the years. The state has a robust public health cadre and an efficient public health system, which ensures that the state has some of the best health indicators in the country (Gaitonde et al. 2020). It is one of the states which has achieved several of the Sustainable Development Goals and is close to achieving several others (Vijayakumar 2019). The exemplary maternal and child health care system of the state is a model for the country. The logistics and supply chain management of medicines, medicinal products and devices, the Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation, is highly efficient in maintaining an uninterrupted supply chain throughout the state (Joy and Scaria 2018). The Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme is one of the earliest insurance-based universal health coverage models in the country (Sundari and Vidhyapriya 2016). The public health and primary care infrastructure in the state is one of the best developed in the country and enjoys a high level of trust in the community for various services (Baidya et al. 2014). A previous exploration of trust in the public health system in Tamil Nadu revealed a high level of trust in the primary care system for maternal and child health services as well as for common minor ailments especially in the rural areas and among the poor (Gopichandran and Chetlapalli 2013).

Mistrust in the Health System in Tamil Nadu

However, the public health system has equally faced a few instances of trust deficit with respect to management of outbreaks and infectious disease control operations. During the annual dengue outbreaks, the public health system has been blamed of lack of transparency of reporting cases with dengue (Lopez et al. 2015). During the dengue epidemic of 2017, the state imposed severe restrictive measures such as random unannounced inspection of households for mosquito breeding, forced entry into houses for inspection and imposing of monetary penalties on households with mosquito breeding, all of which were perceived as highly restrictive and forceful (Express News Service 2017). There is some evidence that the system is not trusted for being sensitive to the needs and experiences of the community. Thus, there is a fine balance between trust and mistrust in the public health system in Tamil Nadu.

Criticism of the Health System’s COVID-19 Response and Erosion of Confidence

Tamil Nadu was criticized for not testing enough persons in the early days of the pandemic (Bhat 2020). But, it gradually increased its testing capacity and by 27 April, it had reached a testing capacity of about 7000 tests per day at a rate of 687.3 tests per million population, which is higher than the other big states in India like Gujrat, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh (The Hindu Data Team 2020). Another major criticism was the implementation of non-scientific interventions for infection control. In some districts, the state installed ‘disinfection tunnels’ which sprayed disinfection solution on people who walked through it, much like a drive through car wash. But this was heavily criticized as the harms of this procedure are more than the benefits, and the state issued a recommendation to close such walk-through disinfection tunnels (IANS 2020). The government was also criticized as suppressing information on the number of cases and number of deaths due to COVID-19, which the officials have denied (Kumar 2020). The state was performing well in its COVID-19 control strategies, when the biggest setback came in early April with a spike of cases, all associated with attendance at a conference in New Delhi (Subramanian 2020b). The state was criticized initially for identifying a religious minority group as being responsible for this spike. This perpetuated a severe bout of stigmatization of the religious group in the community. But subsequently, the officials took efforts to mitigate the discrimination against the religious group by talking about it and spreading awareness that the illness is not associated with any religion (Ramakrishnan 2020). The Chief Minister of the state went on record during a press meet that the state will achieve zero cases of COVID-19 as the lockdown was successful, which was heavily criticized for being unrealistic and uninformed by data (Subramanian 2020a). All of these criticisms have contributed to erosion of confidence in the ability of the health system to control the spread of the infection.

This delicate balance between trust-mistrust and eroding confidence in the health system is likely to influence the cooperation of the people with the system in the measures to control the pandemic. Therefore, during this crisis period, it is important for the health system to function in a manner that fosters trust and confidence, thus encouraging cooperation with the state’s interventions.

Implementing a Trustworthy Pandemic Risk Management Strategy

Simple strategies if adopted by the Tamil Nadu health system can foster trust and confidence, which is very much needed during this crisis.

A robust risk communication strategy that strikes a balance between transparency and avoiding unnecessary panic among the people must be evolved to promote trust and confidence building (Vijaykumar and Raamkumar 2018). Such a transparent communication provides credible information to the people. This helps people perceive the seriousness of the situation and cooperate with the public health interventions. The Tamil Nadu health system brings out a daily news bulletin and shares it with the media. Ensuring that this line of open and transparent communication is continued is particularly important. Close attention to the words used in reporting, the flow of provision of information, avoiding unnecessary sensationalism and providing accurate facts are strategies that can attempt to strike this delicate balance. In the background of a past history of lack of transparency described in the previous section, demonstration of the openness of information is very important to nourish trust.

The interventions that the state is adopting to control the pandemic must be backed by sound evidence and must be scientifically valid. If not, it will lead to harm to the people and cause gross trust erosion. Use of evidence-based interventions generates a feeling among people that whatever interventions that are being provided are well intentioned.

There is significant social stigma associated with being identified as a patient with COVID-19 (Ramakrishnan 2020). The health workers visit the home of the patient, paste stickers on their door indicating that it is a quarantined house, mark an indelible seal on the hand of the quarantined person and carry out disinfection activities in and around the house of the patient. These interventions invade the privacy of individuals and breaches confidentiality of the health information of the people. It subjects people to shame and stigmatization. This is likely to prevent more and more people from reporting their symptoms and not coming forward for testing in order to escape the stigma associated with the disease. On one hand, these interventions are important to contain the rapid spread of the infection; they also force people to hide from the system out of fear of shame and stigma. This can heavily impact on the success of the containment strategies. Preventing public display of the details of infected persons, protecting the privacy of the infected to the maximum extent possible, treating the infected person with respect and dignity and ensuring equal treatment of all people who are infected can promote trust.

Community engagement can be carried out for most public health interventions (Schoch-Spana et al. 2007). Community-based active surveillance in the containment areas by volunteers, community-based quarantine and isolation facilities with active community participation, community policing of lockdown measures and distribution of lockdown relief materials through local leaders are all potential community engagement strategies, all of which can encourage trust and promote cooperation. Community engagement helps to ensure a sense of ownership of the intervention by the community. It also ensures that the interventions are appropriate and acceptable to them. Community engagement gives voice to the affected community and therefore helps to adopt the public health interventions to the values and preferences of the people.

Primary care services are fundamental rights as they address social determinants of health and are basis to the health and well-being of the people. Therefore, there is an ethical imperative to build a resilient health system that can continue to offer routine primary care services such as maternal and child health services, immunization and non-communicable disease services (Martineau 2016). The state has taken several measures to ensure the uninterrupted maternal and child health services and services for non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. Women who are due for delivery have been enumerated and the system sends ambulances to the homes of these women to pick them up and drop them back after safe delivery in a hospital. Similarly, patients on haemodialysis as well as cancer chemotherapy are picked up and dropped in their homes to ensure uninterrupted services (Chandna 2020). These interventions help foster confidence and trust. However, these services do not reach everyone in the state, and those who do not receive these services develop a sense of being let down by the system and experience an erosion of confidence. Building a resilient health system that withstands the stress of such pandemics and continues to offer regular services is an important measure to build trustworthiness.

Conclusion

Pandemics are very unsettling times for people. There is an ambient environment of uncertainty and anxiety. It is in such situations that having a trustworthy health system goes a long way in ensuring safety and well-being of people. In Tamil Nadu though trust in the health system is strong, there are some experiences in the past and some interventions during the COVID-19 control measures which have eroded people’s confidence in the system. The health system must now work towards ensuring that the response fosters trust in the people and encourages cooperation to the heavily restrictive public health measures, which are likely to continue for protracted timelines.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely acknowledge the contributions of Dr Priyadarshini Chidambaram, Assistant Professor, Department of Community Medicine, MS Ramaiah Medical College, Bengaluru, in reviewing a previous draft of this manuscript and giving critical inputs.

Author Contributions

VG, SS, MJK conceptualized the content of the manuscript.

VG drafted the manuscript.

SS and MJK critically reviewed and edited the manuscript.

VG, SS and MJK have read and approved the content of the manuscript and accept responsibility for the content.

Data Availability

Not Applicable

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Not Applicable

Consent to Participate

Not Applicable

Consent for Publication

Not Applicable

Code Availability

Not Applicable

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Baidya M, Gopichandran V, Kosalram K. Patient-physician trust among adults of rural Tamil Nadu: A community-based survey. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2014;60(1):21–26. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.128802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, Prajwal. 2020. Are states like TN testing enough people for COVID-19? Public health experts say no. The News Minute, 15 March 2020. https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/are-states-tn-testing-enough-people-COVID-19-public-health-experts-say-no-120261. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Chandna, Himani. 2020. Tamil Nadu is containing COVID-19 well, and it is not following bhilwara model. The Print, 17 April 2020. https://theprint.in/health/tamil-nadu-is-containing-COVID-19-well-and-it-is-not-following-bhilwara-model/403663/. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Directorate of Public Health and Preventive Medicine. 2020. Daily report on public health measures taken for COVID-19. Media Bulletin 21.04.2020. State Control Room, Directorate of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Health and Family Welfare Department, Government of Tamil Nadu. https://stopcorona.tn.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Media-Bulletin-21.04.2020.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Earle, Timothy C. 2010. Trust in risk management: a model-based review of empirical research. Risk Analysis 30 (4): 541–574. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Earle TC, Siegrist M, Gutscher H. Trust, risk perception and the TCC model of cooperation. In: Earle TC, editor. Trust in Cooperative Risk Management: Uncertainty and scepticism in the public mind. London: Routledge; 2012. pp. 19–68. [Google Scholar]

- Express News Service. 2017. 4,000 legal notices issued in dengue drive in Tamil Nadu: director of public health. New Indian Express, 27 August 2017. http://www.newindianexpress.com/states/tamil-nadu/2017/aug/27/4000-legal-notices-issued-in-dengue-drive-in-tamil-nadu%2D%2Ddirector-of-public-health-1648735.html. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Gaitonde, Rakhal, Miguel San Sebastian, and Anna-Karin Hurtig. 2020. Dissonances and disconnects: The life and times of community-based accountability in the national rural health mission in Tamil Nadu, India. BMC Health Services Research 20 (1): 89. 10.1186/s12913-020-4917-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gopichandran V, Chetlapalli SK. Dimensions and determinants of trust in health care in resource poor settings-a qualitative exploration. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79(4):613–639. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. 2020. India: COVID-19 lockdown puts poor at risk. Human Rights Watch, 27 March 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/27/india-COVID-19-lockdown-puts-poor-risk. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- IANS. 2020. No more COVID-19 disinfectant tunnels in Tamil Nadu. Times of India, 16 April 2020. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/no-more-COVID-19-disinfectant-tunnels-in-tamil-nadu/articleshow/75179604.cms. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Josephine M., Serena. 2020. COVID-19: Here’s what Tamil Nadu has been doing since January. The Hindu, 25 March 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/COVID-19-heres-what-tamil-nadu-has-been-doing-since-january/article31161945.ece. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Joy M, Scaria R. Health expenditure and access disparities in India: Should not the TNMSC model be adopted nationwide? International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews. 2018;5(3):620–623. [Google Scholar]

- Kehoe, Susan M., and J. Rick Ponting. 2003. Value importance and value congruence as determinants of trust in health policy actors. Social Science & Medicine 57 (6): 1065–1075. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00485-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S. Vijay. 2020. We are not suppressing figures regarding COVID-19, says TN health minister. The Hindu, 23 March 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/we-are-not-suppressing-figures-regarding-COVID-19-says-tamil-nadu-health-minister/article31138349.ece. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Lopez, Aloysius Xavier, A.M.P., and Zubeda Hamid. 2015. State view: The case of dengue management and its can of worms. The Hindu, 1 November 2015. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/state-view-the-case-of-dengue-management-and-its-can-of-worms/article7828098.ece. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Martineau FP. People-centred health systems: Building more resilient health systems in the wake of the ebola crisis. International Health. 2016;8(5):307–309. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihw029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minstry of Health and Family Welfare. 2020. Containment plan for large outbreaks: Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID 19). https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/3ContainmentPlanforLargeOutbreaksofCOVID19Final.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- O’Neill, Onora. 2002. Autonomy and trust in bioethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ramakrishnan, Sukshma. 2020. Tamil Nadu: After battling deadly coronavirus, they are fighting stigma. Times of India, 20 April 2020. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/after-battling-deadly-coronavirus-they-are-fighting-stigma/articleshow/75244901.cms. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Schoch-Spana M, Franco C, Nuzzo JB, Usenza C. Community engagement: Leadership tool for catastrophic health events. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism : Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science. 2007;5(1):8–25. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2006.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, Lakshmi. 2020a. Experts question TN CM’s statement that COVID-19 cases will come down in 3 days. The Week, 17 April 2020. https://www.theweek.in/news/india/2020/04/17/experts-question-tamil-nadu-cm-statement-that-COVID-19-cases-will-come-down-in-3-days.html. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Subramanian, Lakshmi. 2020b. Was Tamil Nadu Govt late to realise coronavirus risk among Jamaat delegates? The Week, 3 April 2020. https://www.theweek.in/news/india/2020/04/03/was-tamil-nadu-govt-late-to-realise-to-coronavirus-risk-among-jamaat-delegates.html. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Sundari MM, Vidhyapriya P. Changing face of indian health insurance industry (with special reference with chief minister comprehensive health insurance scheme (CMCHIS)) Asian Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Humanities. 2016;6(5):310–326. doi: 10.5958/2249-7315.2016.00118.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Hindu. 2020. Coronavirus: Restrictions in Tamil Nadu from March 24 to April 1, 2020. The Hindu, 23 March 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/coronavirus-restrictions-in-tamil-nadu-from-march-24-to-april-1-2020/article31145171.ece. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- The Hindu Data Team. 2020. COVID-19: State-wise tracker for coronavirus cases, deaths and testing rates. The Hindu, updated 18 April 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/data/COVID-19-state-wise-tracker-for-coronavirus-cases-deaths-and-testing-rates/article31248444.ece. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Trivedi, Saurabh. 2020. Coronavirus: The story of India’s largest COVID-19 cluster. The Hindu, 11 April 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-nizamuddin-tablighi-jamaat-markaz-the-story-of-indias-largest-COVID-19-cluster/article31313698.ece. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- UN News. 2020. COVID-19: Lockdown across India, in line with WHO guidance. UN News, 24 March 2020. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/03/1060132. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- van der Weerd W, Timmermans DRM, Beaujean DJMA, Oudhoff J, van Steenbergen JE. Monitoring the level of government trust, risk perception and intention of the general public to adopt protective measures during the influenza a (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):575. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar, Sanjay. 2019. T.N. retains third spot in SDG index. The Hindu, 31 December 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/tnretains-third-spot-in-sdg-index/article30439905.ece. Accessed 22 May 2020.

- Vijaykumar, Santosh, and Aravind Sesagiri Raamkumar. 2018. Zika reveals India’s risk communication challenges and needs. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 3 (3): 240–244. 10.20529/IJME.2018.027. [DOI] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation report - 100. World Health Organization, 29 April 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed 22 May 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable