Abstract

Introduction:

We aim to determine racial disparities and their modifying factors in risk for Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia among cognitively normal 65 years or older individuals.

Methods:

Longitudinal data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set on 1229 African Americans (AAs) and 6679 Caucasians were analyzed for the risk of AD using competing risk models with death as a competing event.

Results:

Major AD risk factors modified racial differences which, when statistically significant, occurred only with older age among APOE ε4 negative individuals, but also with younger age among APOE ε4 positive individuals. The racial differences favored AAs among individuals with BMI less than 30, but Caucasians among individuals with a high BMI (≥30), and were additionally modified by sex, education, hypertension, and smoking status.

Conclusions:

The presence, direction, and relative magnitude of racial disparity for AD represent an interactive function of major AD and cerebrovascular risk factors.

Keywords: racial disparity, risk of Alzheimer disease, competing risk survival model, interactions

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is an irreversible neurodegenerative disease that affects 5.7 million mostly elderly Americans [1]. Examinations of AD risks in cognitively normal elderly populations of African Americans (AAs) and Caucasians may help the understanding of racial disparities and the factors that may modify such differences. The enhanced understanding of racial disparities will in turn improve AD diagnosis and prognosis across races and inform the design and analysis of prevention trials of AD as well as public health policy.

Studies of racial disparities in dementia and AD have reported conflicting results, perhaps because the interactions of other risk factors, such as Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 status, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and education, were not taken into account. A number of epidemiologic studies of dementia risk concluded that AAs possess higher prevalence and incidence of dementia [2-6]. After a clinical diagnosis of AD, however, a slower rate of cognitive decline [7] and longer survival [8] in AAs than Caucasians were reported. Studies of possible racial disparities in neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid concentrations (CSF) biomarkers of AD are emerging. Two biomarker studies reported that AAs had higher amyloid deposition by PET standardized uptake value ratio [9] and thinner magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) cortical thickness than Caucasians among those who were already amyloid positive [10]. One study [11] found that the CSF concentrations of total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau at position 181 (p-tau), as well as MRI-based hippocampal volume, were lower in AAs versus Caucasians. These findings on CSF biomarkers are replicated by another recent independent study [12] which further reported that the racial disparities in CSF biomarkers are modified by APOE ε4. Given that CSF t-tau and p-tau are more downstream AD biomarkers ‘closer to’ the initiation of cognitive impairments [13-15], these findings suggest a potentially lower risk of developing AD symptoms in cognitively normal AAs compared to Caucasians, and that such racial difference may depend on APOE ε4 and other AD risk factors. Some brain autopsy studies found no racial difference in the overall prevalence of neuropathological lesions, including senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that are characteristics of AD [16,17], but others reported more AD neuropathology in AAs than Caucasians on demented individuals before death [18], and higher AD frequency in Caucasians than AAs [19].

This study tests the primary hypothesis that cognitively normal elderly AAs and Caucasians have differential risk profiles of developing AD dementia that depend interactively on AD risk factors including APOE ε4 status, baseline age, sex, baseline BMI, and education.

Methods

Setting

In 2002, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) convened a Clinical Task Force to establish standardized clinical and cognitive assessment protocols for all NIA-funded AD Centers (ADCs) that were characterized by uniform methods and diagnostic criteria [19-20]. This Uniform Data Set (UDS) was designed to provide data to support collaborative research initiatives across the ADCs. Since 2005, the NIA has mandated that all eligible US ADCs’ research participants be evaluated with the UDS protocol, and required that longitudinal data from the UDS through annual follow-ups be submitted to the University of Washington’s National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC).

We requested in 2018 the UDS (March 2018 data freeze) of the NACC, which included all participants from 37 ADCs throughout the United States from 2005 to 2018 (currently, there are 31 funded ADCs). All participants were consented at each ADC to share their data for analyses.

Participants

The inclusion criteria are baseline age 65 years or older, cognitive normality at baseline as defined by a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [21] score of 0, and availability of longitudinal UDS data through annual follow-ups. Only AAs and Caucasians are included in the study. Individuals with self-identified mixed race are excluded from the study.

Measures

The UDS obtains demographic data, clinical features of AD and other dementias, and neuropsychological test scores of participants at annual visits. Details of clinical and cognitive assessments were described previously [19, 20]. Briefly, the presence or absence of dementia and, when present, its severity are operationalized in the UDS with the CDR [21]. A global CDR score of 0 corresponds to cognitive normality, and CDR scores of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 indicate very mild, mild, moderate, and severe dementia, respectively. The psychometric testing includes the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [22] and measures for the following cognitive domains: episodic memory, working memory, semantic knowledge, executive function and attention, and visuospatial ability [19, 20]. The UDS requires an etiologic diagnosis be determined for cognitively impaired participants as assigned by either a consensus team or the examining physician [23]. Vital signs, including participant height and weight, are collected at baseline and at annual follow-up. Race is self-reported in the UDS, and its categories are consistent with the National Institute of Health guidelines.

The NACC also collects APOE genotypes, obtained through standard techniques by ADCs using either a blood draw or buccal swab and subsequent genotyping, and merged with the UDS. APOE ε4 positive participants possess one or two ε4 alleles, while APOE ε4 negative participants possesses none.

Statistical analyses

This analysis used NACC UDS (March 2018 data freeze) data from 37 ADCs. Participant characteristics at baseline were summarized by the median and interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables, and frequencies/percentages for qualitative variables for each race, and compared between the races by a Wilcoxon rank sum test for quantitative variables and by a Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables.

The primary outcome of the study is the ‘survival’ time from baseline to the onset of AD dementia symptoms, defined as the first occurrence after baseline of a CDR ≥0.5 with a primary etiologic diagnosis of AD. Causes of cognitive decline other than AD, regardless of whether they were primary or contributory, were not treated as ‘events’ in the analyses. The survival time for participants who either discontinued UDS follow-up or never received a CDR ≥0.5 with a primary etiologic diagnosis of AD during the entire follow-up was treated as statistically right-censored, using the time the participants had stayed in the UDS follow-up [24]. Death was considered as a competing event to incident AD. The Fine and Gray semiparametric proportional hazards model [24] was applied to analyze time to incident AD in the competing risk survival modeling framework. To account for potential heterogeneity across the ADCs, ADCs were incorporated as strata in the model which allowed varying baseline sub-distribution hazards across the ADCs. The unadjusted analyses estimated the cumulative incidence curve of AD dementia for each race, and tested the difference between AAs and Caucasians using Gray’s K-sample statistic [25]. The adjusted analyses included the six major AD risk factors, race, APOE ε4, sex, baseline age, education (>12 yrs vs. ≤12 yrs), baseline BMI (≥30 vs. <30), as well as their interactions. We focused on the model with all main effects and all possible two-way and three-way interactions. Specifically, the tests of 20 three-way interactions from the six risk factors are the primary analyses. To control for the possible inflation of false-positives in the tests of 20 three-way interactions, Hochberg’s step-down procedure was used [26]. Further analyses examined major cerebrovascular risk factors (see Supplemental Table A1) and their potential contributions to the racial disparity in the risk of AD dementia.

All analyses were implemented in the R statistical computing language (version 3.3.1) [27]. The cumulative incidence curve of AD dementia was estimated using the cuminc function, and the Fine and Gray models were fitted using the R functions finegray and coxph in the cmprsk package (version 2.2-7) [28].

Results

Participant characteristics

The study included 1229 AAs and 6679 Caucasians who were cognitively normal at baseline and aged 65 years or older. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The participants were assessed annually for a median duration of 4.41 years, with similar follow-up between Caucasian participants (median=4.44 years) and AAs (median=4.29 years. See Supplemental Table A2 for detailed statistics on annual follow-ups). The median age at baseline was slightly younger for the AAs (73.33 years) than for the Caucasians (75.17 years, p<0.001). The median MMSE score at baseline was slightly lower for the AAs versus the Caucasians (28 vs. 29; p<0.0001). Women represented a greater proportion of AAs in comparison to Caucasians (p<0.001). AAs received less education than Caucasians (p<0.0001), had a higher proportion of positive APOE ε4 (p<0.0001), a higher proportion of high BMI (≥30) at baseline (p<0.0001). During the follow-up, more Caucasians died prior to the onset of AD dementia in comparison to AAs (p=0.0038).

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics and follow up time, in all participants and by race

| Characteristics | All (N=7908) | AA (N=1229) | Caucasian (N=6679) | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age at 1st visit (yrs): median (IQR) | 74.83 (70.08~80.833) | 73.33 (69.25~78.5) | 75.17(70.33~81.33) | <0.0001 | |||

| Follow up (yrs): median (IQR) | 4.405 (2.075~7.511) | 4.293 (2.075~7.211) | 4.441 (2.259~7.603) | 0.0503 | |||

| MMSE at 1st visit: median (IQR) | 29 (28~30) | 28 (27~30) | 29 (28~30) | <0.0001 | |||

| Sex | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Women | 5087 | 64.33 | 974 | 79.25 | 4113 | 61.58 | |

| Men | 2821 | 35.67 | 255 | 20.75 | 2566 | 38.42 | |

| Education (yrs): median, IQR | 16 (14~18) | 14 (12~17) | 16 (14~18) | <0.0001 | |||

| Education | <0.0001 | ||||||

| <=12 yrs | 1510 | 19.16 | 400 | 32.57 | 1110 | 16.68 | |

| >12 yrs | 6371 | 80.84 | 828 | 67.43 | 5543 | 83.32 | |

| APOE ε status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 22 | 45 | 0.64 | 11 | 1.08 | 34 | 0.57 | |

| 32 | 886 | 12.65 | 154 | 15.07 | 732 | 12.24 | |

| 33 | 4088 | 58.37 | 506 | 49.51 | 3582 | 59.88 | |

| 34 | 1669 | 23.83 | 284 | 27.79 | 1385 | 23.15 | |

| 42 | 178 | 2.54 | 44 | 4.31 | 134 | 2.24 | |

| 44 | 138 | 1.97 | 23 | 2.25 | 115 | 1.92 | |

| Baseline BMI | <0.0001 | ||||||

| <30 | 5443 | 75.04 | 621 | 55.25 | 4822 | 78.68 | |

| >=30 | 1810 | 24.96 | 503 | 44.75 | 1307 | 21.32 | |

| Vital status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Alive | 6657 | 84.18 | 1104 | 89.83 | 5553 | 83.14 | |

| Dead | 1251 | 15.82 | 125 | 10.17 | 1126 | 16.86 | |

p values were from two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test for quantitative characteristics and from Fisher’s exact test for qualitative characteristics between AA and Caucasian.

IQR=Interquartile Range; MMSE=Mini Mental State Examination.

Cumulative incidence curves of AD dementia

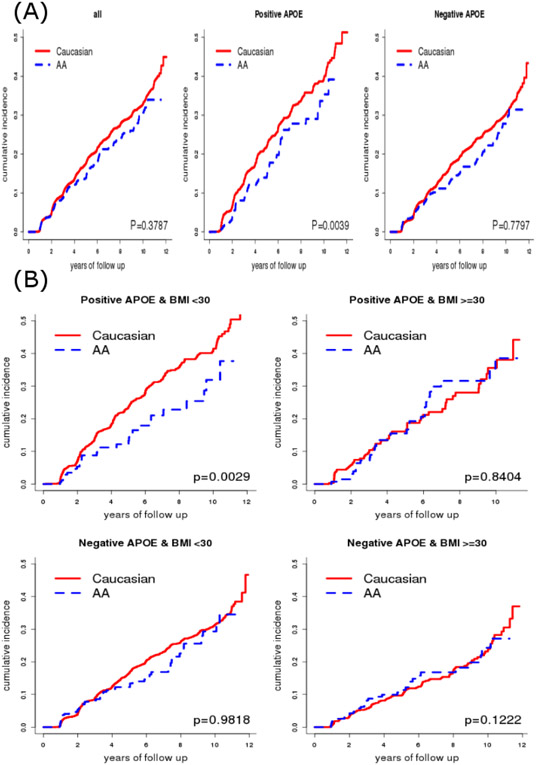

During the follow-up, 1529 (1330 Caucasians and 199 AAs) developed AD dementia. The unadjusted analyses on all participants revealed a lower, but not significantly different cumulative incidence of AD dementia for AAs than for Caucasians (p=0.3787, Figure 1 Panel A left). When further restricted to APOE ε4 positive participants, however, AAs had a significantly lower risk of AD dementia than Caucasians (p=0.0039, Figure 1 Panel A middle). In contrast, no racial difference was observed in the risk of AD dementia (p=0.7797, Figure 1 Panel A right) among APOE ε4 negative participants. When further stratified by baseline BMI (≥30 vs. <30), AAs had a significantly lower risk of AD dementia than Caucasians only on APOE ε4 positive participants with a low BMI (p=0.0029, Figure 1 Panel B); there was a trend of higher risk in AAs among APOE ε4 negative participants with a high BMI (p=0.1222).

Figure 1.

Estimated cumulative incidence curve of AD dementia in all participants (Panel A left), in APOE ε4 positive (Panel A middle) and negative (Panel A right) participants, and in participant groups jointly classified by APOE ε4 and BMI (Panel B)

Risk of AD dementia as an interactive function of risk factors

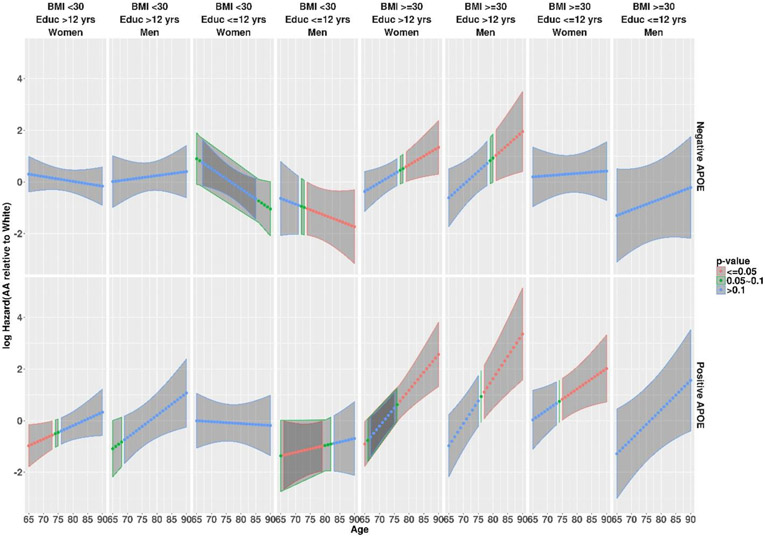

Further adjusted analyses assessed the risk of developing AD dementia simultaneously as a multivariate function of not only race and APOE ε4 and baseline BMI, but also baseline age, education, and sex as well as their interactions (Table 2). After multiplicity adjustments, Table 2 revealed several significant three-way interactions involving race: between race and APOE ε4 and baseline age (p=0.0153), between race and baseline BMI and baseline age (p=0.0057), and between race and sex and education (p=0.0246). Hence, the racial differences were modified by baseline age, APOE ε4, baseline BMI, sex, and education. Figure 2 presents the hazards difference function (also see Supplemental Table A3), along with its 95% confidence interval band in which a negative hazards difference indicates a racial difference favoring AAs (i.e., AAs had a lower risk relative to Caucasians), along with the p-values (visualized by colors) indicating the statistical significance of whether the hazards difference is zero. The racial differences, when statistically significant, occurred only with older age among APOE ε4 negative individuals, but also with much younger age among APOE ε4 positive individuals. The racial differences, when statistically significant, favored AAs among individuals with BMI less than 30, but Caucasians among individuals with a high BMI (≥30), and were additionally modified by sex and education. At the mean age of 75.85 years (Table 3), AAs had a lower risk of AD than Caucasians only on men but not women if both BMI and education were low, whereas no racial difference existed if education was high, regardless of sex, BMI, and APOE ε4 status. Finally, there were other significant three-way interactions on the risk of AD dementia not involving race: between APOE ε4 and sex and baseline age (p=0.0187), between baseline age and education and BMI (p=0.0026), between sex and baseline age and BMI (p=0.0005), and between sex and education and BMI (p=0.0010). Sensitivity analyses by defining the “events” only on those whose CDR reached a minimum of 0.5 during the follow-up and did not reverse back from the final visit revealed largely consistent results. More analyses examined the possible contribution of major cerebrovascular risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, smoking) collected by the NACC UDS to the observed racial differences. These analyses revealed two more significant three-way interactions involving race: between race and education and hypertension (p=0.0009), and between race and education and smoking (p=0.0021), suggesting that hypertension and smoking further modified racial differences in the risk of AD (see Supplemental Table A4 (A5) for the estimated risk difference between AAs and Caucasians for participant groups jointly defined by APOE ε4, sex, BMI, education, and hypertension (smoking status)).

Table 2.

Hazards ratio (HR) for developing AD dementia (95% CI) and p-values estimated from the Fine and Gray sub-distribution model with main effects, two- and three-way interactions of race, APOE ε4, baseline age, sex, BMI, and education. The reference population is Caucasian women with ≤12 years of education and <30 BMI at the mean baseline of the entire cohort (=75.85 years).

| Effect | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| RACE (AA vs. White) | 1.0571(0.5873~1.9028) | 0.8531 |

| APOE (+ vs −) | 1.9471(1.2913~2.9361) | 0.0015 |

| SEX (M vs. F) | 2.3735(1.5559~3.6208) | <0.0001 |

| AGE | 1.0253(1.0008~1.0505) | 0.0431 |

| EDUC (>12 yrs vs. <=12 yrs) | 0.9124(0.6833~1.2182) | 0.5340 |

| BMI (>=30 vs. <30) | 0.9876(0.5647~1.7273) | 0.9652 |

| RACE:APOE | 0.872(0.3928~1.9357) | 0.7363 |

| RACE:SEX | 0.3102(0.1076~0.894) | 0.0302 |

| RACE:AGE | 0.925(0.8645~0.9897) | 0.0238 |

| RACE:EDUC | 1.0449(0.5361~2.0367) | 0.8974 |

| RACE:BMI | 1.2701(0.5456~2.9566) | 0.5792 |

| APOE:SEX | 0.5811(0.2988~1.13) | 0.1096 |

| APOE:AGE | 0.9861(0.9479~1.0258) | 0.4871 |

| APOE:EDUC | 1.2395(0.7911~1.942) | 0.3486 |

| APOE:BMI | 0.4455(0.207~0.9586) | 0.0386 |

| SEX:AGE | 0.9534(0.9205~0.9874) | 0.0076 |

| SEX:EDUC | 0.6036(0.3837~0.9495) | 0.0290 |

| SEX:BMI | 0.2571(0.1134~0.5825) | 0.0011 |

| AGE:EDUC | 1.0069(0.9808~1.0338) | 0.6067 |

| AGE:BMI | 1.0543(1.001~1.1104) | 0.0457 |

| EDUC:BMI | 0.7686(0.418~1.4131) | 0.3969 |

| RACE:APOE:SEX | 1.1958(0.4756~3.0063) | 0.7039 |

| RACE:APOE:AGE | 1.0731(1.0136~1.1361) | 0.0153 |

| RACE:APOE:EDUC | 0.6893(0.2965~1.6024) | 0.3873 |

| RACE:APOE:BMI | 2.0935(0.9295~4.7152) | 0.0745 |

| RACE:SEX:AGE | 1.0348(0.9659~1.1087) | 0.3307 |

| RACE:SEX:EDUC | 3.4957(1.1738~10.4101) | 0.0246 |

| RACE:SEX:BMI | 1.0473(0.3889~2.82) | 0.9272 |

| RACE:AGE:EDUC | 1.0611(0.9959~1.1307) | 0.0668 |

| RACE:AGE:BMI | 1.0909(1.0256~1.1603) | 0.0057 |

| RACE:EDUC:BMI | 1.0352(0.4118~2.602) | 0.9414 |

| APOE:SEX:AGE | 0.9604(0.9285~0.9933) | 0.0187 |

| APOE:SEX:EDUC | 0.9526(0.4761~1.9062) | 0.8910 |

| APOE:SEX:BMI | 1.6497(0.848~3.2094) | 0.1404 |

| APOE:AGE:EDUC | 1.0092(0.9687~1.0513) | 0.6622 |

| APOE:AGE:BMI | 0.9526(0.9101~0.9972) | 0.0373 |

| APOE:EDUC:BMI | 1.4131(0.6397~3.1215) | 0.3925 |

| SEX:AGE:EDUC | 1.0222(0.9841~1.0617) | 0.2569 |

| SEX:AGE:BMI | 1.0845(1.0357~1.1355) | 0.0005 |

| SEX:EDUC:BMI | 4.0866(1.7656~9.459) | 0.0010 |

| AGE:EDUC:BMI | 0.9268(0.8821~0.9738) | 0.0026 |

EDUC=Education, APOE=APOE ε4, AGE=Baseline age-75.85 in years, BMI=Baseline BMI. P-value tests whether each regression coefficient (i.e., the logarithm of a HR) equals to 0.

Figure 2.

Estimated racial difference in risk for AD dementia between AAs and Caucasians in logarithmic scale, as a function of baseline age for sixteen participant groups jointly defined by APOE ε4, sex, BMI, and education (Educ). A negative difference indicates lower AD risk in AAs relative to Caucasians, and a positive difference indicates higher risk in AAs. Red color indicates p values <0.05, green p values in 0.05~0.1, and blue p values >0.1, for testing the risk difference against 0.

Table 3:

Estimated risk difference (AA-Caucasian) for developing AD dementia between AAs and Caucasians in logarithmic scale, standard error, test statistic (against 0), and p-value for sixteen participants groups jointly defined by APOE ε4, sex, BMI, and education at the mean baseline age of the entire cohort (=75.85 years)

|

APOE ε4 |

Sex | Education | BMI | Risk Differences (AAs-Caucasians) |

Standard Error |

Test Statistic |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Men | >12 yrs | <30 | −0.1499 | 0.4084 | −0.3670 | 0.7136 |

| Positive | Women | >12 yrs | <30 | −0.4096 | 0.2621 | −1.5631 | 0.1180 |

| Positive | Men | <=12 yrs | <30 | −1.0733 | 0.4927 | −2.1783 | 0.0294 |

| Positive | Women | <=12 yrs | <30 | −0.0815 | 0.3639 | −0.2239 | 0.8228 |

| Negative | Men | >12 yrs | <30 | 0.1804 | 0.2836 | 0.6362 | 0.5247 |

| Negative | Women | >12 yrs | <30 | 0.0994 | 0.2129 | 0.4671 | 0.6404 |

| Negative | Men | <=12 yrs | <30 | −1.1151 | 0.5076 | −2.1967 | 0.0280 |

| Negative | Women | <=12 yrs | <30 | 0.0555 | 0.2999 | 0.1851 | 0.8531 |

| Positive | Men | >12 yrs | >=30 | 0.9088 | 0.5125 | 1.7732 | 0.0762 |

| Positive | Women | >12 yrs | >=30 | 0.6029 | 0.3232 | 1.8653 | 0.0621 |

| Positive | Men | <=12 yrs | >=30 | −0.0491 | 0.7315 | −0.0672 | 0.9465 |

| Positive | Women | <=12 yrs | >=30 | 0.8965 | 0.4111 | 2.1806 | 0.0292 |

| Negative | Men | >12 yrs | >=30 | 0.5002 | 0.4158 | 1.2032 | 0.2289 |

| Negative | Women | >12 yrs | >=30 | 0.3731 | 0.2665 | 1.3999 | 0.1615 |

| Negative | Men | <=12 yrs | >=30 | −0.8298 | 0.7604 | −1.0912 | 0.2752 |

| Negative | Women | <=12 yrs | >=30 | 0.2946 | 0.3734 | 0.7889 | 0.4302 |

P-value tests whether the risk difference (in logarithmic scale) equals to 0.

Discussion

In this large longitudinal cohort study on the risk of AD dementia, 1229 AAs and 6679 Caucasians who were cognitively normal and 65 years or older at baseline from 37 ADCs were clinically well characterized annually through the standard NACC UDS protocol. We found that racial disparity in the risk of developing AD dementia depended on multiple AD risk factors in such an interactive manner that it would be misleading to simply state there was or was not a racial difference without clearly specifying the participant populations as defined by these risk factors. Specifically, the presence or absence of the racial difference, and if present, whether it favors AAs or Caucasians and how much the relative magnitude is, all jointly depend on APOE ε4, baseline age, BMI, education, sex, and cerebrovascular factors.

A large portion of similar elderly adults as in this study has been reported to have ‘preclinical AD’ [29], which indicates the absence of dementia symptoms in spite of AD neuropathological change in the brain. Accumulating biomarker evidence for a temporal cascade of changes in CSF biomarkers and PET amyloid uptakes [14,15] also supports the concept of preclinical AD with Aβ accumulation in the brain as a very early neuropathological process in AD. Neurofibrillary tangles and neuronal death, however, appear to begin during the preclinical phase of AD, but represents a closer event to the cognitive changes. By the time of early symptoms, neuronal cell death is already significant in CA1 of hippocampus and layer II of the entorhinal cortex [30-31]. Hence, the acceleration of tau aggregation, detectable by CSF t-tau and p-tau, may mark the transition from cognitive normality to symptom onset. Importantly, these biomarker changes are all clinically relevant because in cognitively normal elderly individuals, a high level of t-tau and p-tau and a high ratio of CSF t-tau/Aβ42 or a high level of cerebral Aβ burden as shown by PET imaging predict the rate of longitudinal cognitive decline and the conversion to early symptomatic AD [15, 32]. The established predictability of clinical/cognitive outcomes by CSF biomarkers, especially t-tau and p-tau, coupled with two most recent independent biomarker studies of racial disparity which reported that the CSF t-tau and p-tau were lower in AAs versus Caucasians [11,12], may partly explain the racial differences in the risk of AD dementia. One study further reported a significant race by APOE ε4 interaction for both CSF t-tau and p-tau [12], suggesting that the racial disparities in these biomarkers, and hence in the more downstream clinical changes, may depend on APOE ε4 status, consistent with our current findings. Specifically, both biomarker studies [11,12] are cross-sectional with mean ages from 67.5 to 71.5 years, close to the younger end of the baseline age in the current study where we found that AAs had a lower risk of AD dementia mostly in APOE ε4 positive participants with a low BMI. Putting all these together, our independent findings on the APOE ε4–dependent racial disparity in the risk of AD are consistent with the latest biomarker findings.

Our findings may help explain the conflicting reports in the literature regarding racial differences in AD. Most previous studies of racial disparity on dementia were cross-sectional, had small sample sizes of AAs, included all types of dementia, and assumed uniform racial differences regardless of AD risk factors. In contrast, our study was longitudinal with a large sample size of AAs, focused specifically on AD dementia, and assessed the risk of AD dementia in a comprehensive manner that allowed potential differential racial differences as a function of all major AD risk factors and their interactions. The interactive and even directional roles that APOE ε4, baseline age and BMI, and other factors played in the racial difference of AD risk highlight the likelihood that some of the conflicting findings in the literature may be due to the ignorance of important risk factors in the analyses.

Our findings have major implications for future studies of AD. First, the interactive effects between race and other risk factors such as APOE ε4, age, sex, BMI, and education mandate that future studies of AD analyze the risk comprehensively and interactively. Simple analytic approaches, such as single-factor models or even multiple factors models without assessing the interactions across major risk factors, may result in oversimplified and biased findings on racial disparity. Next, secondary prevention randomized clinical trials (RCTs), the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s (A4) trial (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02008357), the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) trials [33], and the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative (API) trial [34] are ongoing. Primary prevention trials are currently planned [35]. Our findings suggest that the design and analyses of prevention RCTs account for the differential risk profiles of AD between AAs and Caucasians. A single set of inclusion/exclusion criteria for these trials may not apply uniformly to both AAs and Caucasians.

Limitations

The NACC UDS is an observational database. Hence, the reported racial differences is subject to selection bias that may manifest in different ways in AAs and Caucasians, may also be confounded by factors that may or may not be collected by the database, and hence may not generalize to the general population. Socioeconomic factors and access to healthcare may play a major role in the observed racial differences, and the NACC UDS has minimum data on socioeconomic factors beyond education. Lack of biomarkers and cause of death (for those who died) in the UDS prevents us from directly linking the racial disparity in biomarkers to that in the risk of pathologically confirmed AD. Finally, although our findings are consistent with most recent biomarker reports [11,12] and autopsy studies [18], the underlying mechanisms of the racial differences remain poorly understood. The fundamental question of whether AD, as currently defined, is the same disease between AAs and Caucasians remains open. More research is needed to disentangle the genetic, environmental, and their interactive effects to explain racial disparities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute on Aging R01AG053550 (Xiong), P50 AG005681 (Morris), and P01 AG0399131 (Morris), and NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976 (Kukull)

NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

CX and JL and DC and SA and WK and JCM declare no conflict related to this work.

References

- [1].Alzheimer's Association (2018) 2018 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia 14, 367–429. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fillenbaum GG, Heyman A, Huber MS, Woodbury MA, Leiss J, Schmader KE, Bohannon A, Trapp-Moen B (1998) The prevalence and 3-year incidence of dementia in older Black and White community residents. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 51, 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schoenberg BS, Anderson DW, Haerer AF (1985) Severe dementia. Prevalence and clinical features in a biracial US population. Arch Neurol 42, 740–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Ives DG, Lopez OL, Jagust W, Breitner JCS, Jones B, Lyketsos C, Dulberg C (2004) Incidence and prevalence of dementia in the cardiovascular health study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 52, 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Whitmer RA (2016) Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimers & Dementia 12, 216–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, Merchant C, Lantigua R, Costa R, Stern Y, Mayeux R (2001) Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology 56, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Li Y, Aggarwal NT, Gilley DW, McCann JJ, Evans DA (2005) Racial differences in the progression of cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13, 959–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Perez-Stable EJ, Stewart A, Barnes D, Kurland BF, Miller BL (2008) Race/ethnic differences in AD survival in US Alzheimer's Disease Centers. Neurology 70, 1163–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gottesman RF, Schneider ALC, Zhou Y, Chen XQ, Green E, Gupta N, Knopman DS, Mintz A, Rahmim A, Sharrett AR, Wagenknecht LE, Wong DF, Mosley TH (2016) The ARIC-PET amyloid imaging study Brain amyloid differences by age, race, sex, and APOE. Neurology 87, 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McDonough IM (2017) Beta-amyloid and Cortical Thickness Reveal Racial Disparities in Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease. Neuroimage-Clinical 16, 659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Howell JC, Watts KD, Parker MW, Wu J, Kollhoff A, Wingo TS, Dorbin CD, Qiu D, Hu WT (2017) Race modifies the relationship between cognition and Alzheimer's disease cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Alzheimers Res Ther 9, 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Morris JC, Schindler SE, McCue LM, Moulder KL, Benzinger TLS, Cruchaga C, Fagan AM, Grant E, Gordon BA, Holtzman DM, Xiong C (2019) Assessment of Racial Disparities in Biomarkers for Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol 76, 264–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, Marcus DS, Cairns NJ, Xie X, Blazey TM, Holtzman DM, Santacruz A, Buckles V, Oliver A, Moulder K, Aisen PS, Ghetti B, Klunk WE, McDade E, Martins RN, Masters CL, Mayeux R, Ringman JM, Rossor MN, Schofield PR, Sperling RA, Salloway S, Morris JC, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer N (2012) Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 367, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, Trojanowski JQ (2010) Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer's pathological cascade. Lancet Neurology 9, 119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Xiong CJ, Jasielec MS, Weng H, Fagan AM, Benzinger TLS, Head D, Hassenstab J, Grant E, Sutphen CL, Buckles V, Moulder KL, Morris JC (2016) Longitudinal relationships among biomarkers for Alzheimer disease in the Adult Children Study. Neurology 86, 1499–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Miller FD, Hicks SP, D'Amato CJ, Landis JR (1984) A descriptive study of neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in an autopsy population. Am J Epidemiol 120, 331–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Graff-Radford NR, Besser LM, Crook JE, Kukull WA, Dickson DW (2016) Neuropathologic differences by race from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center. Alzheimers Dement 12, 669–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].de la Monte SM, Hutchins GM, Moore GW (1989) Racial differences in the etiology of dementia and frequency of Alzheimer lesions in the brain. J Natl Med Assoc 81, 644–652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Morris JC, Weintraub S, Chui HC, Cummings J, DeCarli C, Ferris S, Foster NL, Galasko D, Graff-Radford N, Peskind ER, Beekly D, Ramos EM, Kukull WA (2006) The uniform data set (UDS): Clinical and cognitive variables and descriptive data from Alzheimer disease centers. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders 20, 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Weintraub S, Besser L, Dodge HH, Teylan M, Ferris S, Goldstein FC, Giordani B, Kramer J, Loewenstein D, Marson D, Mungas D, Salmon D, Welsh-Bohmer K, Zhou XH, Shirk SD, Atri A, Kukull WA, Phelps C, Morris JC (2018) Version 3 of the Alzheimer Disease Centers' Neuropsychological Test Battery in the Uniform Data Set (UDS). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 32, 10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Morris JC (1993) The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 43, 2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Beekly DL, Ramos EM, van Belle G, Deitrich W, Clark AD, Jacka ME, Kukull WA, Centers NI-AsD (2004) The National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) Database: an Alzheimer disease database. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 18, 270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fine JP, Gray RJ (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association 94, 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gray RJ (1988) A Class of K-Sample Tests for Comparing the Cumulative Incidence of a Competing Risk. Annals of Statistics 16, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- [27].R Core Team (2017) R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Gray B (2014) cmprsk: Subdistribution Analysis of Competing Risks.

- [29].Morris JC, Roe CM, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Goate AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA (2010) APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol 67, 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Price JL, Ko AI, Wade MJ, Tsou SK, McKeel DW, Morris JC (2001) Neuron number in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 58, 1395–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Gomez-Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW Jr., Morris JC, Growdon JH, Hyman BT (1996) Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 16, 4491–4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Fagan AM, Roe CM, Xiong C, Mintun MA, Morris JC, Holtzman DM (2007) Cerebrospinal fluid tau/beta-amyloid(42) ratio as a prediction of cognitive decline in nondemented older adults. Arch Neurol 64, 343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bateman RJ, Benzinger TL, Berry S, Clifford DB, Duggan C, Fagan AM, Fanning K, Farlow MR, Hassenstab J, McDade EM, Mills S, Paumier K, Quintana M, Salloway SP, Santacruz A, Schneider LS, Wang G, Xiong C, Network D-TPCftDIA (2017) The DIAN-TU Next Generation Alzheimer's prevention trial: Adaptive design and disease progression model. Alzheimers Dement 13, 8–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tariot PN, Lopera F, Langbaum JB, Thomas RG, Hendrix S, Schneider LS, Rios-Romenets S, Giraldo M, Acosta N, Tobon C, Ramos C, Espinosa A, Cho W, Ward M, Clayton D, Friesenhahn M, Mackey H, Honigberg L, Sanabria Bohorquez S, Chen K, Walsh T, Langlois C, Reiman EM, Alzheimer's Prevention I (2018) The Alzheimer's Prevention Initiative Autosomal-Dominant Alzheimer's Disease Trial: A study of crenezumab versus placebo in preclinical PSEN1 E280A mutation carriers to evaluate efficacy and safety in the treatment of autosomal-dominant Alzheimer's disease, including a placebo-treated noncarrier cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 4, 150–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].McDade E, Bateman RJ (2017) Stop Alzheimer's before it starts. Nature 547, 153–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.