Abstract

Background

Health care workers (HCWs) are essential for the delivery of health care services in conflict areas and in rebuilding health systems post-conflict.

Objective

The aim of this study was to systematically identify and map the published evidence on HCWs in conflict and post-conflict settings. Our ultimate aim is to inform researchers and funders on research gap on this subject and support relevant stakeholders by providing them with a comprehensive resource of evidence about HCWs in conflict and post-conflict settings on a global scale.

Methods

We conducted a systematic mapping of the literature. We included a wide range of study designs, addressing any type of personnel providing health services in either conflict or post-conflict settings. We conducted a descriptive analysis of the general characteristics of the included papers and built two interactive systematic maps organized by country, study design and theme.

Results

Out of 13,863 identified citations, we included a total of 474 studies: 304 on conflict settings, 149 on post-conflict settings, and 21 on both conflict and post-conflict settings. For conflict settings, the most studied counties were Iraq (15%), Syria (15%), Israel (10%), and the State of Palestine (9%). The most common types of publication were opinion pieces in conflict settings (39%), and primary studies (33%) in post-conflict settings. In addition, most of the first and corresponding authors were affiliated with countries different from the country focus of the paper. Violence against health workers was the most tackled theme of papers reporting on conflict settings, while workforce performance was the most addressed theme by papers reporting on post-conflict settings. The majority of papers in both conflict and post-conflict settings did not report funding sources (81% and 53%) or conflicts of interest of authors (73% and 62%), and around half of primary studies did not report on ethical approvals (45% and 41%).

Conclusions

This systematic mapping provides a comprehensive database of evidence about HCWs in conflict and post-conflict settings on a global scale that is often needed to inform policies and strategies on effective workforce planning and management and in reducing emigration. It can also be used to identify evidence for policy-relevant questions, knowledge gaps to direct future primary research, and knowledge clusters.

Introduction

Health care workers (HCWs) are essential for the delivery of health care services in conflict areas and in rebuilding health systems post-conflict. However, HCWs in conflict areas around the world are being threatened, detained, and killed. For instance, in Syria, Physicians for Humans Rights has reported that, since the start of the conflict till December 2017, 847 medical personnel have been killed [1]. In Afghanistan, around 92 attacks against health facilities and health workers killed 14 health workers and four caretakers in the period extending from March 1, 2015 till February 10, 2016 [2].

Direct attacks and insecurity have led to the exodus of HCWs from conflict areas. In Syria, 50% of the health workers and 95% of physicians living in Aleppo have left the country since 2011. In Iraq, almost half of the health professionals have emigrated since 2014 [2]. In Nigeria, almost all health workers have escaped areas controlled by Boko Haram since 2012, leading to the closure of 450 health facilities [2].

The resulting shortage of HCWs has devastating effects on the delivery of, and access to health care not only during conflicts but also in the aftermath of war. The post-conflict settings are characterized by poor health outcomes due to limited availability of HCWs and disruption of health systems [3, 4]. Rebuilding the health workforce is critical to address health needs and strengthen health systems. Furthermore, post-conflict settings present a window of opportunity to develop responsive and evidence-informed strategies and policies to address defects in the supply, distribution and performance of the health workforce [4, 5].

In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) passed a resolution that calls on the WHO Director General for leadership in documenting evidence of attacks against health workers, facilities, and patients in situations of armed conflict [6]. A scoping review on HCWs in Syria and other “Arab Spring” countries showed scarcity of research evidence on HCWs in the setting of the “Arab Spring” [7]. While that review revealed a number of themes of interest (e.g., violence against health care workers, education, practicing in conflict setting, migration), it focused on only one region and did not address post-conflict settings. Therefore, the objective of this study was to systematically identify and map the published evidence on HCWs in both conflict and post-conflict settings. Our ultimate aim is to inform researchers and funders on research gap on this subject and support relevant stakeholders by providing them with a comprehensive resource of evidence about HCWs in conflict and post-conflict settings on a global scale.

Methods

Study design

This systematic mapping was based on a protocol registered with Open Science Framework [8]. We followed standard methodology for screening, data extraction and coding, data analysis, and visualizing the findings in systematic mapping. Contrary to systematic reviews, systematic mapping does not aim to answer a specific question but instead “collates, describes and catalogues available evidence (e.g. primary, secondary, quantitative or qualitative) relating to a topic of interest” [9]. In accordance with the definition of systematic maps, this study is a “systematic visual presentation of the availability of relevant evidence,” but not the content of the evidence [10] for the topic of health care workers in conflict and post-conflict settings. The studies included in a systematic map can be used to identify evidence for policy-relevant questions, knowledge gaps to direct future primary research, and knowledge clusters. Knowledge clusters are sub-sets of evidence that may be suitable for secondary research, for example systematic review.

Eligibility criteria

Population of interest

Our population of interest consisted of any personnel providing health services such as: midwives, nurses, paramedics, pharmacists, physicians, laboratory technicians, community health workers as well as medical students and trainees. We excluded military HCWs, because we aimed to focus on the delivery of health care primarily to civilians.

Setting of interest

We included both conflict and post-conflict settings. We considered both conflicts between and within states [11]. We focused on contemporary conflicts that started after or were ongoing in the 1990s. We defined conflicts as international armed conflicts between two or more states or non-international armed conflicts between non-governmental armed groups or with governmental forces [11]. Post-conflict settings are considered as a stage of recovery of the state from a conflict or crisis and a stage of rebuilding and reconstruction starting from emergency and stabilization followed by transition and recovery, and peace and development [5, 12, 13]. We referred to the description used by the authors when specifying whether the setting of the study was conflict or post-conflict.

Study design

We included all types of study designs, including news, editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces, technical reports, primary studies, narrative reviews, and systematic reviews. We excluded conference abstracts. We restricted our eligibility criteria to papers published after the year 2000 to better reflect the current challenges facing health systems and the new aspects of contemporary conflicts.

Literature search

We searched the following electronic databases: Medline (Ovid), PubMed, EMBASE (Ovid), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature CINAHL (EBSCOT) on July 2017. We also searched the ReBUILD Consortium Resources webpage and the Human Resources for Health (HRH) Global Resource Center.

We used both index terms and free text words for the two following concepts: (1) health care workers and (2) conflict and post-conflict settings. The search terms and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms for each database were developed with the guidance of an information specialist. We did not limit the search to specific languages. S1 File provides the search strategies for the different databases.

Selection process

Title and abstract screening

Teams of two reviewers used the above eligibility criteria to screen titles and abstracts of identified citations in duplicate and independently for potential eligibility. We retrieved the full texts for citations judged as potentially eligible by at least one of the two reviewers.

Full-text screening

Teams of two reviewers used the above eligibility criteria to screen the full texts in duplicate and independently for eligibility. The teams of two reviewers resolved disagreement by discussion or with the help of a third reviewer. We used standardized and pilot-tested screening forms. We conducted calibration exercises to ensure the validity of the selection process.

Data extraction and coding

Two reviewers extracted data using standardized and pilot tested forms. The reviewers resolved any disagreement by discussion and when needed with the help of a third reviewer. We conducted calibration exercises to ensure the validity of the data abstraction process.

We extracted from each paper the following information:

Citation;

Year of publication;

Countr(ies) subject of the paper;

Type of publication (e.g., news, editorial, correspondence, opinion pieces, primary study, narrative review, systematic review, case study, technical report)

Language of publication;

- Authors’ information:

- ○ Total number of authors;

- ○ Number of authors from the countr(ies) subject of the paper;

- ○ Country of affiliation of the first author;

- ○ Country of affiliation of the contact author;

Characteristics of the journal of publication (name and impact factor);

Setting (conflict or post-conflict);

Theme(s) of the study for conflict settings: we adopted the themes from a previous scoping review on health care workers in the setting of Arab Spring [7]: violence against health care workers, education, practicing in conflict setting, migration, and other (S2 File);

Theme(s) of the study for post-conflict settings: we adopted the theme(s) from a previous review on human resource management in post-conflict health systems [5]: workforce supply, workforce distribution, workforce performance, and other (S2 File);

Reporting of funding of the study;

Reporting of conflict of interest of authors;

Ethical approval of the study.

For the themes, data was coded as ‘other’ if it did not address any of the existing themes, or if it covered an emerging theme and an existing one. Using an iterative process of review and refinement, data coded as ‘other’ was revisited, collated and new themes were generated.

Critical appraisal

We did not appraise the quality of included studies since our review is consistent with standard systematic mapping methodology [9].

Data analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis of the general characteristics of the included papers using frequencies. We also used the results of this review to build two interactive and visual systematic evidence maps on (1) HCWs in conflict settings and (2) HCWs in post-conflict settings. We represented the evidence maps by country, type of publication and themes. We have also provided direct links to the included studies in the maps.

Results

Study selection

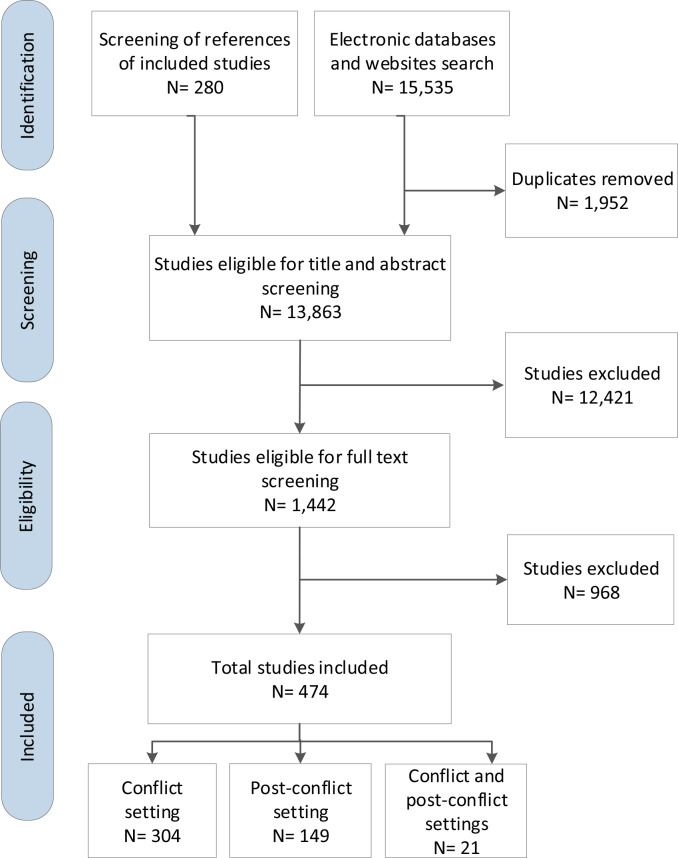

Fig 1 summarizes the study selection process. Out of 13,863 identified unique citations, we included a total of 474 studies [4, 14–470]: 304 on conflict settings, 149 on post-conflict settings, and 21 on both conflict and post-conflict settings. We excluded 968 papers for the following reasons: not study design of interest (n = 63); not setting of interest (n = 324); not population of interest (n = 538); and not timeframe of interest (e.g. ceasefire was called on before 1990) (n = 43). We present below our findings on the characteristics of the included papers, journals, authors, funding, conflicts of interest, and ethics reporting. We also report on the two generated systematic maps.

Fig 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) study flow diagram for selection.

Characteristics of the included papers

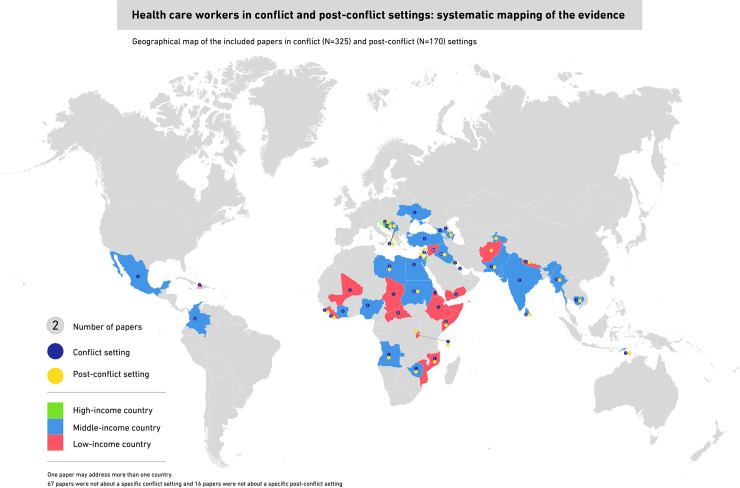

Fig 2 presents a geographical map of the countries focus of the included papers (S3 File). A description of the included studies is also presented in S4 File. The majority of the articles included in this systematic mapping were about low-income countries. For conflict settings (N = 325), 79% of the included papers addressed specific conflicts related to 47 countries. The most studied counties were Iraq (15%), Syria (15%), Israel (10%), and the State of Palestine (9%). For post-conflict settings (N = 170), 91% of the included papers addressed specific settings related to 32 countries. Sierra Leone (14%) was the most studied country followed by Uganda (11%) and Afghanistan (9%). The majority of papers on conflict and post-conflict were published in English language (98% and 100% respectively).

Fig 2. Geographical map of the included papers in conflict (N = 325) and post-conflict (N = 170) settings.

Table 1 represents the themes focus of the papers on health care workers in conflict (N = 325) and post-conflict (N = 170) settings. More than one theme was reported in 33% of the papers on HCWs in conflict settings and in 52% of the papers on HCWs in post-conflict settings. In addition to the themes about HCWs in conflict settings reported in Bou-Karroum et al. (2018) [7], three additional themes emerged in this review, and those were the role of HCWs in peace promotion or protecting health care, mental health of HCWs, and medical ethics. Most of the included papers on conflict settings addressed the theme of violence against health workers (41%), followed by health or medical practice (34%) and education (21%). For post-conflict settings, besides the themes adopted from Roome et al. (2014) [5], an emerging theme was the mental health of HCWs. The majority of the included papers on post-conflict settings addressed the workforce performance theme (77%) followed by workforce supply (58%).

Table 1. Topics focus of the papers on health care workers in conflict (N = 325) and post-conflict (N = 170) settings.

| Topics of the papers* | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Conflict setting (N = 325) | |

| • Violence against health care workers | 133 (41) |

| • Health or medical practice | 109 (34) |

| • Education | 67 (21) |

| • Role in peace promotion or protecting health care | 48 (15) |

| • Mental health | 42 (13) |

| • Migration | 37 (11) |

| • Medical ethics | 16 (5) |

| Post-conflict setting (N = 170) | |

| • Workforce performance | 131 (77) |

| • Workforce supply | 98 (58) |

| • Workforce distribution | 40 (24) |

| • Retention | 22 (13) |

| • Mental health | 8 (5) |

*One paper may address more than one topic.

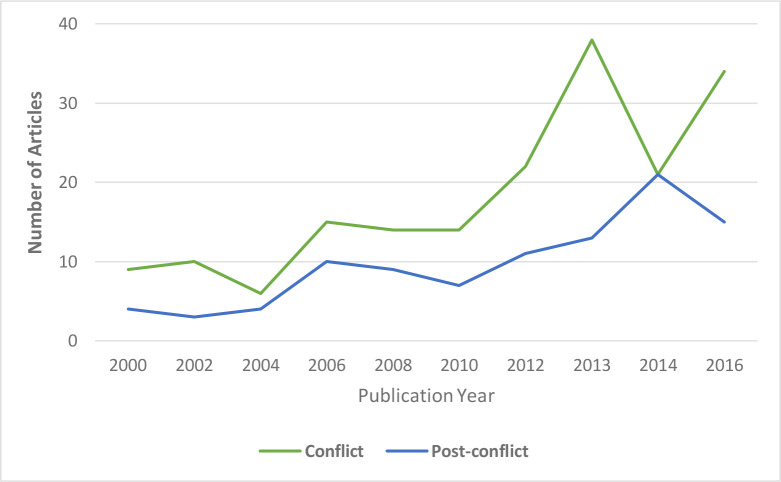

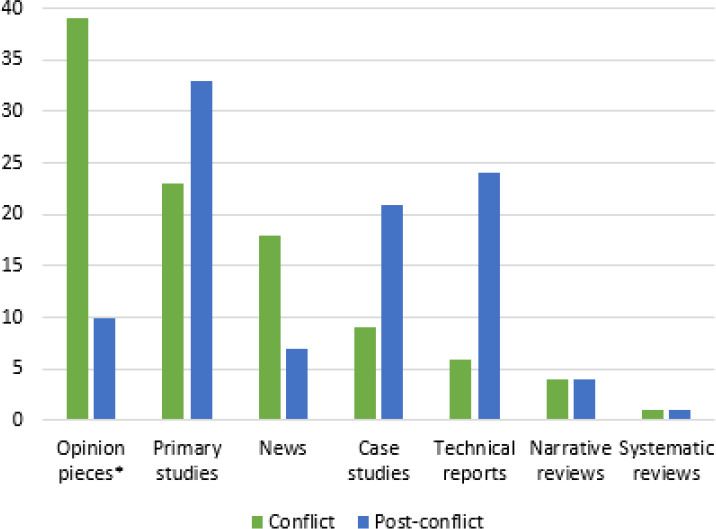

Fig 3 shows the annual production rate of the included papers. The year for the peak number of publications was 2013 for conflict settings and 2014 for post-conflict settings. Fig 4 shows the types of publication of the included papers. Opinion pieces represented the most common type of publication (39%) in conflict settings, followed by primary studies (23%) and news (18%). Primary studies were the most common type of publication (33%) in post-conflict settings followed by technical reports (24%) and case studies (21%).

Fig 3. Publication year of articles of the papers included in the systematic maps in conflict (N = 325) and post-conflict settings*.

Fig 4. Types of publication* of the included papers on health care workers in conflict (N = 325) and post-conflict (N = 170) settings.

Characteristics of the journals

For conflict settings (N = 325), the included papers were published across 134 journals. The journals that published the highest proportions of included studies were the Lancet (15%), BMJ (7%), and CMAJ (5%). Out of the 134 journals, 90 journals (67%) had 2017 impact factors. 230 of the 325 papers were published in these 90 journals and had a median impact factor of 4.74 (IQR = 1.74–27.94).

For post-conflict settings (N = 170), the included papers were published across 79 journals. The journals that published the highest number of included studies were the Lancet (6%), Conflict and Health (5%), and Health Policy and Planning (5%). Out of the 79 journals, 51 journals (65%) had 2017 impact factors. 92 of the 170 papers were published in these 51 journals and had a median impact factor of 2.42 (IQR = 1.61–3.31).

Characteristics of the authors

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the authors of the included papers. For conflict settings, 69% of the included papers reported affiliations of authors and addressed specific conflict(s). Out of these, 40% had at least 1 author affiliated with the country focus of the paper. The median percentage of authors affiliated with the country focus of the paper was null (0%) (IQR = 0–75). In addition, most of the first and corresponding authors were affiliated with countries different from the country focus of the paper (68% and 70% respectively), mainly the United States of America (42% and 39% respectively) followed by the United Kingdom (21% and 24% respectively).

Table 2. Characteristics of authors of the included papers in conflict (N = 325) and post-conflict (N = 170) settings.

| Any/all authors | Conflict (N = 325) | Post-conflict (N = 170) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||

| Papers with named authors | 302 (93) | 161 (95) |

| Papers reporting affiliations of authors | 279 (86) | 141 (83) |

| N = 224* (69) | N = 128* (75) | |

| Papers with at least 1 author affiliated with country focus of paper | 90 (40) | 68 (53) |

| % authors affiliated with country focus of paper (median [IQR]) | 0 (0–75) | 20 (0–67) |

| First author | N = 224 | N = 128 |

| Country focus of paper | 68 (30) | 42 (33) |

| Different country | 151 (68) | 84 (66) |

| - United States of America | 63 (42) | 2 (32) |

| - United Kingdom | 31 (21) | 31 (37) |

| - European countries other than UK | 20 (13) | 7 (8) |

| - Canada | 15 (10) | 7 (8) |

| - Other | 22 (14) | 12 (15) |

| Independent | 5 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Corresponding author | N = 213§ | N = 125§§ |

| Country focus of paper | 60 (28) | 29 (23) |

| Different country | 148 (70) | 94 (75) |

| - United States of America | 58 (39) | 29 (31) |

| - United Kingdom | 35 (24) | 38 (40) |

| - European countries other than UK | 20 (14) | 8 (9) |

| - Canada | 14 (9) | 7 (7) |

| - Other | 21 (14) | 12 (13) |

| Independent | 5 (2) | 2 (2) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range

* This is the number of papers reporting affiliations of authors and addressing a specific setting.

§ The corresponding author was unclear in 11 papers.

§§ The corresponding author was unclear in 3 papers.

For post-conflict settings, 75% of the included papers reported affiliations of authors and addressed specific conflict(s). Out of these, about half (53%) had at least 1 author affiliated with the country focus of the paper. The median percentage of authors affiliated with the country focus of the paper was 20% (IQR = 0–67). Similar to conflict settings, most of the first and corresponding authors were affiliated with countries different from the country focus of the paper (66% and 75% respectively), mainly the United Kingdom (37% and 40% respectively) followed by the United States of America (32 and 31% respectively).

Funding, conflicts of interest and ethics reporting characteristics

Table 3 shows the funding, conflicts of interest, and ethics reporting characteristics of the included papers. For conflict settings, most of the included papers did not report funding sources (81%) or statements of conflicts of interest of authors (73%). Out of the included primary studies, about half (55%) reported ethical approval to conduct the studies. For post-conflict settings, about half of the included papers did not report funding sources (53%) and 62% did not report on the conflicts of interest of authors. Out of the included primary studies, 59% reported ethical approval.

Table 3. Funding, conflicts of interest and ethics reporting characteristics of the included papers in conflict (N = 325) and post-conflict (N = 170) settings.

| Conflict (N = 325) | Post-conflict (N = 170) | |

| Funding sources | n (%) | |

| Not reported | 263 (81) | 90 (53) |

| Reported as funded | 50 (15) | 75 (44) |

| Reported as not funded | 12 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Conflicts of interest | ||

| Not reported | 238 (73) | 106 (62) |

| Reported | 87 (27) | 64 (38) |

| Ethical approval of primary studies | Conflict (N = 76) | Post-conflict (N = 56) |

| Not reported | 33 (44) | 21 (38) |

| Reported as approved | 42 (55) | 33 (59) |

| Reported as not required | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

Systematic maps

The two systematic maps, which represent a visual and interactive overview of the evidence on health care workers in conflict and post-conflict settings, can be freely accessed and downloaded using the following links for conflict settings (http://evidencemaphcw.com/gapmap/conflict) and for post-conflict settings (http://evidencemaphcw.com/gapmap/post-conflict). The maps allow data to be filtered and sorted by type of primary studies (experimental, survey, qualitative, mixed-methods, and document analysis). The maps contain links that redirect the user to PubMed or other databases, to access the title and abstract of included papers, when available.

The systematic map for conflict settings shows that papers on violence and attacks against HCWs were mainly not country specific, about Syria, or about Iraq. The theme of health or medical practice of HCWs was mainly addressed in Iraq and Syria. Education and training of health care workers was the theme mainly addressed in Iraq and Myanmar. Primary studies on HCWs in conflict setting were mainly about Israel and the State of Palestine with a focus on mental health in both countries.

The systematic map for post-conflict settings shows that the theme of workforce performance was mainly about Sierra Leone and Uganda. The papers on workforce supply were mainly not country specific, about Afghanistan, or about Sierra Leone. Primary studies on HCWs in post-conflict setting were mainly about Sierra Leone and Afghanistan with a focus on workforce performance in both countries.

Discussion

This review presents a systematic mapping of the evidence on health care workers in conflict and post-conflict settings. It has uncovered interesting findings relating to the characteristics of the included papers, journals, and authors respectively; as well as the reporting of funding, conflicts of interest, and ethics.

The systematic map for conflict settings shows the scarcity of primary studies conducted in conflict settings with the predominance of news, opinion pieces and commentaries. This is in line with a previous scoping review on health care workers in the setting of Arab Spring that showed the scarcity of research evidence [7]. Similarly, Patel et al. (2017) reported on the lack of baseline and routine data mainly on violence against health workers [304]. In contrast to conflict settings, primary studies represented the most frequent type of publications on health care workers in post-conflict settings. These findings might relate to the specific settings in which the conflict and post-conflict studies were conducted. However, they might also reflect the challenges in conducting primary research in conflict settings, including security concerns, difficulties in obtaining representative samples and with data collection, political bias, lack of tools and methods specific to conflict settings, and insufficient research funding and capacity [1, 304, 471].

The majority of authors (including first and corresponding) of the included papers were affiliated with high income counties, as opposed to being affiliated with the country focus of the paper. This finding may reflect global imbalances in research capacity between high- and low- and middle-income countries [472–474]. Reasons for this imbalance include limited funding, instability, poor research training, collaboration challenges, and shortage of skilled human resources in low and middle income countries [1, 473–477].

As most of the articles addressing health care workers in conflict and post-conflict are about low-income countries, we can infer that conflicts are still taking place in these countries that already suffer from weak health systems [478]. Our findings are consistent with the previously published scoping review focusing on health care workers in the setting of Arab Spring which found that violence was the most tackled theme [7]. Findings for post-conflict settings concur with a previous review by Roome et al. (2014) on human resources management in post-conflict health systems [5]. This shows the need for more studies on the topic of workforce distribution, which is important to ensure equity in health service provision.

Another interesting finding is the low rates of reporting of funding sources and disclosures of conflict of interest by authors of the included studies. This is particularly for papers about HCWs in conflict settings. Indeed, funders may have specific agendas while researchers may have political biases and tendency to take sides [471]. These may lead to distorted research and biased data that could be used to mislead local and international communities and negatively affect policy making. Reporting of funding sources and conflict of interest becomes important to better assess the confidence in the publication, particularly when it reports primary studies or makes policy recommendations.

We also found a relatively low reporting of ethical approvals for primary studies, in both conflict and post-conflict settings. This might be attributed to a weak local research capacity including the absence of or complicated ethical review boards [1]. Reporting and seeking ethical approvals in these settings is important given the vulnerability of individuals living in conflict-affected states [479]. This calls journals publishing research conducted in conflict settings to have stringent policies for reporting funding, conflict of interest and ethical approval.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic mapping of evidence on health care workers in conflict and post-conflict settings. One strength of this study is that we have followed a standardized methodology for conducting and reporting systematic mapping [9]. Further, we have used published frameworks to classify studies on HCWs in conflict and post-conflict settings [5, 7]. One limitation of this study is restricting inclusion to studies published after the year 2000. However, studies published before 2000 might not reflect the current challenges facing health systems and the new aspects of contemporary conflicts. Another limitation of our systematic map is that we relied on the authors’ characterization of the conflict (e.g., conflict or post-conflict), and subsequently we did not differentiate between countries in conflict such as Somalia, Iraq and Syria, and those affected by conflict such as Lebanon.

The findings of this review and the resulting systematic maps can support policy makers working on rebuilding health systems post-conflict. These systematic maps provide a comprehensive resource of evidence about HCWs in conflict and post-conflict settings on a global scale. As such, policymakers as well as researchers can use them to find relevant studies by theme. In addition, the mapped evidence can inform policies and practices to protect, support and address the needs of the health care workers in conflict settings. The evidence identified can also inform efforts and strategies for reconstruction and rebuilding of post-conflict health systems, in particular human resource for health.

The findings also highlight the need to strengthen the capacity of local researchers working in conflict-affected states. Also, they can inform agendas of funders and researchers working in the field of health care workers in conflict and post-conflict settings of potential knowledge gaps. This systematic map will inform areas for potential systematic reviews in the field, and may provide a jumpstart for those reviews, given that the relevant studies have already been identified and organized by theme.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(PDF)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Mahmoud Chmeiss for designing the geographical map of the included papers, Ms. Nour Hemadi for helping in the screening process and Ms. Karen Bou-Karroum, Ms. Rand Al Ghoussaini and Mr. Mark Jreij for helping in the data abstraction process.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

EAA and FEJ received funding from the Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research (CNRS)-American University of Beirut (AUB) and the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research of the World Health Organization (WHO). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Woodward A, Sheahan K, Martineau T, Sondorp E. Health systems research in fragile and conflict affected states: a qualitative study of associated challenges. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2017;15(1):44 10.1186/s12961-017-0204-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conflict SHi. No Protection No Respect. 2016.

- 3.Rubenstein RJHLS. Health in Postconflict and Fragile States. United States Institute of Peace. 2012;Special Report 301.

- 4.Martineau T, McPake B, Theobald S, Raven J, Ensor T, Fustukian S, et al. Leaving no one behind: lessons on rebuilding health systems in conflict- and crisis-affected states. BMJ Global Health. 2017;2(2):e000327 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roome E, Raven J, Martineau T. Human resource management in post-conflict health systems: review of research and knowledge gaps. Conflict and health. 2014;8:18 Epub 2014/10/09. 10.1186/1752-1505-8-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHA WHA. WHO’s response, and role as the health cluster lead, in meeting the growing demands of health in humanitarian emergencies. 2012.

- 7.Bou-Karroum L, Daou KN, Nomier M, El Arnaout N, Fouad FM, El-Jardali F, et al. Health Care Workers in the setting of the "Arab Spring": a scoping review for the Lancet-AUB Commission on Syria. J Glob Health. 2019;9(1):010402–. 10.7189/jogh.09.010402 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khamis AM, Hakoum MB, Bou-Karroum L, Habib JR, Ali A, Guyatt G, et al. Requirements of health policy and services journals for authors to disclose financial and non-financial conflicts of interest: a cross-sectional study. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2017;15(1):80 10.1186/s12961-017-0244-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James KL, Randall NP, Haddaway NR. A methodology for systematic mapping in environmental sciences. Environmental Evidence. 2016;5(1):7 10.1186/s13750-016-0059-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saran A, White H. Evidence and gap maps: a comparison of different approaches. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2018;14(1):1–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ICRC ICotRC. How is the term "Armed Conflict" defined in international humanitarian law? 2008.

- 12.McPake B. Health systems in conflict affected states—are they different from in other low and middle income countries? Early ideas from the work of the ReBUILD programme. ReBuild Consortium; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahonsi BA. Towards more informed responses to gender violence and HIV/AIDS in post-conflict West African settings: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The L. A tribute to aid workers. Lancet. 2006;368(9536):620 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbara A, Orcutt M, Gabbar O. Syria's lost generation of doctors. BMJ. 2015;350:h3479 10.1136/bmj.h3479 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdou R, Romm I, Schiff D, Austad K, Dubal S, Kimmel S, et al. In solidarity with Gaza. Lancet. 2009;373(9660):295 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60042-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abramovitch H. Making war a part of medical education. Israel Medical Association Journal: Imaj. 2013;15(3):174–5. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abrams E. Saving my heart. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2009;181(6–7):E115 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abramsky O. Letter to the Royal College of Physicians (London): Take anti-Israeli politics out of medicine. Israel Medical Association Journal. 2009;11(6):334 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abu-El-Noor NI, Aljeesh YI, Radwan AS, Abu-El-Noor MK, Qddura IA, Khadoura KJ, et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Health Care Providers Following the Israeli Attacks Against Gaza Strip in 2014: A Call for Immediate Policy Actions. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2016;30(2):185–91. 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.08.010 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acerra JR, Iskyan K, Qureshi ZA, Sharma RK. Rebuilding the health care system in Afghanistan: An overview of primary care and emergency services. International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2009;2(2):77–82. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams E. Human rights and health in conflict zones. World of Irish Nursing & Midwifery. 2016;24(8):22–3. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20170113. Revision Date: 20170113. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adil M, Johnstone P, Furber A, Siddiqi K, Khan D. Violence against public health workers during armed conflicts. Lancet. 2013. January 5;381(9860):1 Lancet. 2013;381 North American Edition(9863):293-. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60127-0 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20130222. Revision Date: 20150712. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afkhami AA. Psychiatry and efforts to build community in Iraq. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;171(9):913–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmadzai TK, Maburutse Z, Miller L, Ratnayake R. Protecting public health in Yemen. The Lancet. 2016;388(10061):2739 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed F. The sideline or frontline: where should the UK medical profession stand in times of armed conflict overseas? BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2014;348(7940):26–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20140115. Revision Date: 20150710. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aiga H, Pariyo GW. Violence against health workers during armed conflict. Lancet. 2013. January 26;381(9863):293 Lancet. 2013;381 North American Edition(9874):1276-. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60839-9 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20130517. Revision Date: 20150712. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al Mosawi AJ. Medical education and the physician workforce of Iraq. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2008;28(2):103–5. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20080905. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alasaad S. War diseases revealed by the social media: Massive leishmaniasis outbreak in the Syrian Spring. Parasites and Vectors. 2013;6 (1) (no pagination)(94). . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkan ML, Shwartz S. Medical services for rural Ethiopean Jews in Addis Ababa, 1990–1991. Rural and remote health. 2007;7(4):829 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Kindi S. Violence against doctors in Iraq. The Lancet. 2014;384(9947):954–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allan R. Where are you from? Clinical Medicine. 2007;7(2):101–2. 10.7861/clinmedicine.7-2-101a . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ameh CA, Bishop S, Kongnyuy E, Grady K, Van den Broek N. Challenges to the provision of emergency obstetric care in iraq. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2011;15(1):4–11. 10.1007/s10995-009-0545-3 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20110131. Revision Date: 20150820. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amin NM, Khoshnaw MQ. Medical education and training in Iraq. Lancet. 2003;362(9392):1326 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14580-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anonymous. Defining the limits of public health. Lancet. 2000;355(9204):587 10.1159/000491433 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nurse pledges to stay in war zone. Nursing Standard. 2001;16(5): 4–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20020118. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plea for safety in war zones. Nursing Standard. 2002;16(31):6–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20020614. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Health professions speak out against armed conflict. Canadian Nurse. 2003;99(5):32–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20030711. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anonymous. Help needed for East Timor nurses. Australian nursing journal (July 1993). 2006;14(1):15 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nurses gear up to help treat injured children in war zone. Paediatric Nursing. 2010;22(3):5–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20100604. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charities send aid and staff to Libya. Nursing Standard. 2011;26(1):6–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20110930. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anonymous. A medical crisis in Syria. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):537 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61309-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anonymous. Health Care in Danger: Deliberate Attacks on Health Care during Armed Conflict. PLoS Medicine. 2014;11(6):1–2. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anonymous. The war on Syrian civilians. The Lancet. 2014;383(9915):383 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anonymous. Care for the carers. Nature. 2015;527(7576):7–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anonymous. Syria: a health crisis too great to ignore. Lancet. 2016;388(10039):2 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30936-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nurses' flight worsens Middle Eastern health crisis. Lamp. 2017;74(1):22–3. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20170208. Revision Date: 20170210. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Australia & New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- 48.The L. Syria suffers as the world watches. The Lancet. 2017;389(10074):1075 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arias-López BE. Care and social suffering: nursing within contexts of political violence. Investigacion & Educacion en Enfermeria. 2013;31(1):125–32. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20130606. Revision Date: 20150820. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Mexico & Central/South America. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arie S. Gaddafi's forces attacked hospitals, patients, and health professionals, report confirms. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;343:d5533 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arie S. Charity donations in name of UK doctor killed in Syria rise beyond expectations. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346 (no pagination)(f3592). . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arie S. Family of missing UK doctor says he entered Syria with 20,000 in medical supplies to provide aid. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346 (no pagination)(f681). . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arie S. Investigate death of British doctor in Syria, say campaigners. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;347 (no pagination)(f7647). . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arie S. Islamic State executes 10 doctors for refusing to treat its wounded fighters. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;350:h1963 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Asia MR, Georges JM, Hunter AJ. Research in conflict zones: implications for nurse researchers. Advances in Nursing Science. 2010;33(2):94–100. 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181d52dd4 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20100709. Revision Date: 20150818. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Core Nursing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Austin H. 'The situation is worse than before the war'. Nursing Standard. 2003;17(46):8–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20040116. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bagaric I. Medical services of Croat people in Bosnia and Herzegovina during 1992–1995 war: Losses, adaptation, organization, and transformation. Croatian Medical Journal. 2000;41(2):124–40. 10.1111/idj.12450 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Band-Winterstein T, Koren C. "We take care of the older person, who takes care of us?" Professionals working with older persons in a shared war reality. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2010;29(6):772–92. . [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bar-El Y, Reisner S, Beyar R. Moral dilemmas faced by hospitals in time of war: the Rambam Medical Center during the second Lebanon war. Medicine, health care, and philosophy. 2014;17(1):155–60. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barmania S. Undercover medicine: Treating Syria's wounded. The Lancet. 2012;379(9830):1936–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baroness Cox C. The Baroness Cox of Queensbury. Nursing ethics. 2003;10(4):441–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Batley NJ, Makhoul J, Latif SA. War as a positive medical educational experience. Medical Education. 2008;42(12):1166–71. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20090522. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ben-Ezra M, Bibi H. The Association Between Psychological Distress and Decision Regret During Armed Conflict Among Hospital Personnel. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2016;87(3):515–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ben-Ezra M, Palgi Y, Essar N. Impact of war stress on posttraumatic stress symptoms in hospital personnel. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(3):264–6. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20071130. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben-Ezra M, Palgi Y, Essar N. The impact of exposure to war stress on hospital staff: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42(5):422–3. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ben-Ezra M, Palgi Y, Shrira A, Hamama-Raz Y. Somatization and Psychiatric Symptoms among Hospital Nurses Exposed to War Stressors. Israel Journal of Psychiatry & Related Sciences. 2013;50(3):182–6. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20150904. Revision Date: 20150923. Publication Type: Journal Article. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ben-Ezra M, Palgi Y, Wolf JJ, Shrira A. Psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial functioning among hospital personnel during the Gaza War: a repeated cross-sectional study. Psychiatry research [Internet]. 2011; 189(3):[392–5 pp.]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/483/CN-00801483/frame.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ben-Ezra M, Palgi Y, Wolf JJ, Shrira A. Psychosomatic symptoms among hospital physicians during the Gaza War: a repeated cross-sectional study. Israel journal of psychiatry and related sciences [Internet]. 2011; 48(3):[170–4 pp.]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/330/CN-00804330/frame.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bergovec M, Kuzman T, Rojnic M, Makovic A. Zagreb University School of Medicine: Students' grades during war. Croatian Medical Journal. 2002;43(1):67–70. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Betsi NA, Koudou BG, Cisse G, Tschannen AB, Pignol AM, Ouattara Y, et al. Effect of an armed conflict on human resources and health systems in Cote d'Ivoire: Prevention of and care for people with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care—Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2006;18(4):356–65. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Birch M. A risk worth taking. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987). 2001;16(12):60–1. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Birch M, Ratneswaren S. From Solferino to Sri Lanka: health workers, health information, and international law. Medicine, conflict, and survival. 2009;25(3):191–2. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bloem C, Morris RE, Chisolm-Straker M. Human Trafficking in Areas of Conflict: Health Care Professionals' Duty to Act. AMA journal of ethics. 2017;19(1):72–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bloom JD, Sondorp E. Relations between ethnic Croats and ethnic Serbs at Vukovar General Hospital in wartime and peacetime. Medicine, conflict, and survival. 2006;22(2):110–31. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boehm A. The functions of social service workers at a time of war against a civilian population. Disasters. 2010;34(1):261–86. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bolza R. Delivering hope—and babies—in a war-torn land. Interview by Laura Putre. Hospitals & Health Networks. 2010;84(11):17 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boren D. Physician obligations to help document the atrocities of war. The Virtual Mentor. 2007;9(10):692–4. 10.1001/virtualmentor.2007.9.10.jdsc1-0710 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bradbeer M. Safeguard nurses at war…Cover story about workplace violence, ANJ July 2011. Australian Nursing Journal. 2011;19(4):3–. Language: English. Entry Date: 10.1038/oby.2010.5 Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brook OR. Recollections of a radiology resident at war. Radiology. 2007;244(2):329–30. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brundtland GH, Glinka E, Hausen HZ, D'Avila RL. Open letter: Let us treat patients in Syria. The Lancet. 2013;382(9897):1019–20. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brunham L, Lee P, Pinto A. Medical students not mum on Iraq. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;169(6):541 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burkle FM Jr, Erickson TB, Von Schreeb J, Redmond AD, Kayden S, Van Rooyen M, et al. A declaration to the UN on wars in the Middle East. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lancet; 2017. p. 699–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burkle FM Jr., Erickson T, von Schreeb J, Kayden S, Redmond A, Chan EY, et al. The Solidarity and Health Neutrality of Physicians in War & Peace. PLoS currents. 2017;9:20 10.1371/currents.dis.1a1e352febd595087cbeb83753d93a4c . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burnham G, Malik S, Dhari Al-Shibli AS, Mahjoub AR, Baqer AQ, Baqer ZQ, et al. Understanding the impact of conflict on health services in Iraq: Information from 401 Iraqi refugee doctors in Jordan. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2012;27(1):e51–e64. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Byamungu DC, Ogbeiwi OI. Integrating leprosy control into general health service in a war situation: The level after 5 years in Eastern Congo. Leprosy Review. 2003;74(1):68–78. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carlisle D. In the line of fire. Nursing Standard. 2012;26(39):18–9. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20120622. Revision Date: 20150819. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carmichael JL, Karamouzian M. Deadly professions: violent attacks against aid-workers and the health implications for local populations. International Journal of Health Policy & Management. 2014;2(2):65–7. 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.16 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Casey SE, Mitchell KT, Amisi IM, Haliza MM, Aveledi B, Kalenga P, et al. Use of facility assessment data to improve reproductive health service delivery in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Conflict & Health [Electronic Resource]. 2009;3:12 10.1186/1752-1505-3-12 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Catton H. It takes a brave heart to be a nurse in a war-torn country. RCNi; 2016. p. 28–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Challoner KR, Forget N. Effect of civil war on medical education in Liberia. International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2011;4(1). . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chi PC, Bulage P, Urdal H, Sundby J. Perceptions of the effects of armed conflict on maternal and reproductive health services and outcomes in Burundi and Northern Uganda: A qualitative study. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2015;15 (1) (no pagination)(7). . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Clarfield AM. Close calls. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2009;180(12):E98 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Clark JR. Civilians in a War Zone. Air Medical Journal. 2016;35(5). . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cohn JR, Romirowsky A, Marcus JM. Abuse of health-care workers' neutral status [1]. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1473 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Corcione A, Petrini F, Gristina G, De Robertis E. A statement on the war in Syria from SIAARTI and partners. The Lancet. 2017;389(10064):31 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Coupland R, Cordner S. People missing as a result of armed conflict: standards and guidelines are needed for all, including health professionals. BMJ: British Medical Journal (International Edition). 2003;326(7396):943–4. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20030718. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cousins S. Syrian crisis: Health experts say more can be done. The Lancet. 2015;385(9972):931–4. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Davenport A. Healthcare in Kosovo. Midwifery today with international midwife. 2000;(53):50–2. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Davis M, Goldstein K, Nasser T, Assaf C. Peace through Health: The Role of Health Workers in Preventing Emergency Care Needs. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13(12):1324–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Val D'Espaux S, Madi B, Nasif J, Arabasi M, Raddad S, Madi A, et al. Strengthening mental health care in the health system in the occupied Palestinian territory. Intervention (15718883). 2011;9(3):279–90. 10.1097/WTF.0b013e32834dea41 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20120217. Revision Date: 20150712. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dean E. Nursing in the world's most challenging places. Nursing Standard. 2016;30(48):38–9. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20160801. Revision Date: 20160801. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Double Blind Peer Reviewed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Decker JT, Constantine Brown JL, Tapia J. Learning to Work with Trauma Survivors: Lessons from Tbilisi, Georgia. Social Work in Public Health. 2017;32(1):53–64. 10.1080/19371918.2016.1188744 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.D'Errico NC, Wake CM, Wake RM. Healing Africa? Reflections on the peace-building role of a health-based non governmental organization operating in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Medicine, conflict, and survival. 2010;26(2):145–59. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Devi S. Syria's refugees face a bleak winter. The Lancet. 2012;380(9851):1373–4. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Devi S. Syria's health crisis: 5 years on. The Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1042–3. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Devkota B, van Teijlingen ER. Politicians in apron: case study of rebel health services in Nepal. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2009;21(4):377–84. 10.1177/1010539509342434 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20091204. Revision Date: 20150819. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dewachi O, Skelton M, Nguyen VK, Fouad FM, Sitta GA, Maasri Z, et al. Changing therapeutic geographies of the Iraqi and Syrian wars.[Erratum appears in Lancet. 2014 Feb 1;383(9915):412]. Lancet. 2014;383(9915):449–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62299-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Donaldson RI, Mulligan DA, Nugent K, Cabral M, Saleeby ER, Ansari W, et al. Using tele-education to train civilian physicians in an area of active conflict: certifying iraqi physicians in pediatric advanced life support from the United States. Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;159(3):507–9.e1. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20111118. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Donaldson RI, Shanovich P, Shetty P, Clark E, Aziz S, Morton M, et al. A survey of national physicians working in an active conflict zone: the challenges of emergency medical care in iraq. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine. 2012;27(2):153–61. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20120914. Revision Date: 20150820. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Doocy S, Malik S, Burnham G. Experiences of Iraqi doctors in Jordan during conflict and factors associated with migration. American journal of disaster medicine. 2010;5(1):41–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Duffin C. Aid work 'in jeopardy' as combatants in war zones target charity services. Emergency nurse: the journal of the RCN Accident and Emergency Nursing Association. 2010;18(2):7 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dumont F. On the ground in the Gaza Strip. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2009;180(6):610 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Durham J, Pavignani E, Beesley M, Hill PS. Human resources for health in six healthcare arenas under stress: a qualitative study. Human resources for health. 2015;13:14 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dyer E. Nursing in Goma, Congo. The American journal of nursing. 2002;102(5):87, 9, 91. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Eaton L. Doctors must speak out over war and humanitarian crises. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2001;323(7316):771 . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Eisenkraft A, Gilburd D, Kassirer M, Kreiss Y. What can we learn on medical preparedness from the use of chemical agents against civilians in Syria? American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014;32(2):186 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.El Jamil F, Hamadeh GN, Osman H. Experiences of a support group for interns in the setting of war and political turmoil. Family Medicine. 2007;39(9):656–8. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Elamein M, Bower H, Valderrama C, Zedan D, Rihawi H, Almilaji K, et al. Attacks against health care in Syria, 2015–16: Results from a real-time reporting tool. The Lancet. 2017. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.El-Fiki M, Rosseau G. The 2011 Egyptian revolution: A neurosurgical perspective. World Neurosurgery. 2011;76(1–2):28–32. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Essar N, Ben-Ezra M, Langer S, Palgi Y. Gender differences in response to war stress in hospital personnel: Does profession matter? A preliminary study. European Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;22(2):77–83. . [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zarocostas J. Libya's health system struggles after exodus of foreign medical staff. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;342:d1879 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wisborg T, Murad MK, Edvardsen O, Husum H. Prehospital trauma system in a low-income country: system maturation and adaptation during 8 years. Journal of Trauma. 2008;64(5):1342–8. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20080620. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wilson JF. Physicians contribute professional expertise worldwide. Annals of internal medicine. 2003;138(12):1013–6. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Webster PC. Iraq's growing health crisis. Lancet. 2014;384(9938):119–20. 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61148-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Webster PC. The deadly effects of violence against medical workers in war zones. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2011;183(13):E981–2. 10.1503/cmaj.109-3964 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20111118. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Webster P. Facility attacks in Syria contravene Geneva Convention. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2016;188(7):491–. 10.1503/cmaj.109-5249 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20160903. Revision Date: 20170421. Publication Type: journal article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Webster P. Medical faculties decimated by violence in Iraq. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2009;181(9):576–8. 10.1503/cmaj.109-3035 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Weaver K. Caring for the living and the dead. Nursing Standard. 2004;18(18):18–9. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20050712. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Washington CH, Tyler FJ, Davis J, Shapiro DR, Richards A, Richard M, et al. Trauma training course: innovative teaching models and methods for training health workers in active conflict zones of Eastern Myanmar. International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014;7(1). . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Anderson K. Working in a war zone. Interview by Lynne Wallis. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987). 2001;15(24):19–20. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wakabi W. South Sudan faces grim health and humanitarian situation. The Lancet. 2011;377(9784):2167–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wakabi W. WHO trains surgeons in troubled Somalia. Lancet. 2010;375(9723):1336 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Fernandez G, Boulle P. Where conflict's medical consequences remain unchanged. The Lancet. 2013;381(9870):901 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fisher RC. Musculoskeletal trauma services in Mozambique and Sri Lanka. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2008;466(10):2399–402. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Foghammar L, Jang S, Kyzy GA, Weiss N, Sullivan KA, Gibson-Fall F, et al. Challenges in researching violence affecting health service delivery in complex security environments. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;162:219–26. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.039 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20160724. Revision Date: 20160908. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Allied Health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Footer KH, Meyer S, Sherman SG, Rubenstein L. On the frontline of eastern Burma's chronic conflict—listening to the voices of local health workers. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;120:378–86. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fouad FM, Alameddine M, Coutts A. Human resources in protracted crises: Syrian medical workers. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lancet; 2016. p. 1613–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Fouad FM, Sparrow A, Tarakji A, Alameddine M, El-Jardali F, Coutts AP, et al. Health workers and the weaponisation of health care in Syria: A preliminary inquiry for The Lancet-American University of Beirut Commission on Syria. The Lancet. 2017. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Friedrich MJ. Human rights report details violence against health care workers in Bahrain. JAMA. 2011;306(5):475–6. 10.1001/jama.2011.1091 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Garfield R. Health professionals in Syria. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):205–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61507-X . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Garfield R, Dresden E, Boyle JS. Health care in Iraq. Nursing Outlook. 2003;51(4):171–7. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20031121. Revision Date: 20150818. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gately R. Humanitarian aid to Iraqi Civilians during the war: A US nurse's role. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2004;30(3):230–6. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Gearey J. A call to unite: physicians must help children in areas of conflict. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2007;176(10):1407–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20070713. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Vostanis P. Healthcare professionals in war zones are vulnerable too. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing. 2015;22(10):747–8. 10.1111/jpm.12272 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20151218. Revision Date: 20161130. Publication Type: Editorial. Journal Subset: Core Nursing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Vogel L. UN inaction emboldens attacks on health care. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2016;188(17–18):E415–E6. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Voelker R. Iraqi health minister works to reform, restore neglected system. JAMA—Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(6):639 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Viola JM. On the letters on the war. The American journal of nursing. 2003;103(5):16; discussion . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Veronese G, Pepe A, Massaiu I, De Mol AS, Robbins I. Posttraumatic growth is related to subjective well-being of aid workers exposed to cumulative trauma in Palestine. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2017;54(3):332–56. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Veronese G, Pepe A, Afana A. Conceptualizing the well-being of helpers living and working in war-like conditions: A mixed-method approach. International Social Work. 2016;59(6):938–52. 10.1177/0020872814537855 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20161111. Revision Date: 20170203. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Allied Health. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Veronese G, Pepe A. Sense of Coherence as a Determinant of Psychological Well-Being Across Professional Groups of Aid Workers Exposed to War Trauma. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;18:18 10.1177/0886260515590125 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Veronese G. Self-perceptions of well-being in professional helpers and volunteers operating in war contexts. Journal of health psychology. 2013;18(7):911–25. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Abandonments Varley E., Solidarities and Logics of Care: Hospitals as Sites of Sectarian Conflict in Gilgit-Baltistan. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2016;40(2):159–80. 10.1007/s11013-015-9456-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Varley E. Targeted doctors, missing patients: Obstetric health services and sectarian conflict in Northern Pakistan. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;70(1):61–70. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.VanRooyen M, Venugopal R, Greenough PG. International humanitarian assistance: where do emergency physicians belong? Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2005;23(1):115–31. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20051028. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.VanRooyen MJ, Eliades MJ, Grabowski JG, Stress ME, Juric J, Burkle FM Jr. Medical relief personnel in complex emergencies: perceptions of effectiveness in the former Yugoslavia. Prehospital & Disaster Medicine. 2001;16(3):145–9. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20030711. Revision Date: 20150820. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Urlic I. Recognizing inner and outer realities as a process: On some countertransferential issues of the group conductor. Group Analysis. 2005;38(2):249–63. . [Google Scholar]

- 157.Turk T, Aboshady OA, Albittar A. Studying medicine in crisis: Students' perspectives from Syria. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Taylor & Francis Ltd; 2016. p. 861–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Tschudin V, Schmitz C. The impact of conflict and war on international nursing and ethics. Nursing Ethics. 2003;10(4):354–67. 10.1191/0969733003ne618oa . Language: English. Entry Date: 20050425. Revision Date: 20150818. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Double Blind Peer Reviewed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Tiembre I, Benie J, Coulibaly A, Dagnan S, Ekra D, Coulibaly S, et al. Impact of armed conflict on the health care system of a sanitary district in Cote d'Ivoire. [French] Impact du conflit arme sur le systeme de sante d'un district sanitaire en Cote d'Ivoire. Medecine Tropicale. 2011;71(3):249–52. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Teela KC, Mullany LC, Lee CI, Poh E, Paw P, Masenior N, et al. Community-based delivery of maternal care in conflict-affected areas of eastern Burma: perspectives from lay maternal health workers. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(7):1332–40. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.033 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20090710. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Tanabe M, Robinson K, Lee CI, Leigh JA, Htoo EM, Integer N, et al. Piloting community-based medical care for survivors of sexual assault in conflict-affected Karen State of eastern Burma. Conflict & Health [Electronic Resource]. 2013;7(1):12 10.1186/1752-1505-7-12 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Taira BR, Cherian MN, Yakandawala H, Kesavan R, Samarage SM, DeSilva M. Survey of Emergency and Surgical Capacity in the Conflict-Affected Regions of Sri Lanka. World Journal of Surgery. 2009:1–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Taha AA, Westlake C. Palestinian nurses' lived experiences working in the occupied West Bank. International Nursing Review. 2017;64(1):83–90. 10.1111/inr.12332 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20170216. Revision Date: 20170216. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Continental Europe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Stone-Brown K. Syria: a healthcare system on the brink of collapse. BMJ. 2013;347:f7375 10.1136/bmj.f7375 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Squires A, Sindi A, Fennie K. Health system reconstruction: perspectives of Iraqi physicians. Global Public Health. 2010;5(6):561–77. 10.1080/17441690903473246 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20110107. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Squires A, Sindi A, Fennie K. Reconstructing a health system and a profession: priorities of Iraqi nurses in the Kurdish region. Advances in Nursing Science. 2006;29(1):55–68. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20060804. Revision Date: 20150818. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Southall D. Armed conflict women and girls who are pregnant, infants and children; a neglected public health challenge. What can health professionals do? Early Human Development. 2011;87(11):735–42. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20130830. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Sousa C, Hagopianb A. Conflict, health care and professional perseverance: A qualitative study in the West Bank. Global Public Health. 2011;6(5):520–33. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Solberg K. Gaza's health and humanitarian crisis. The Lancet. 2014;384(9941):389–90. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Slagstad K. Even wars have rules. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening: tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke. 2016;136(10):891 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Skirtz A. Whither the social workers? why the silence? Social Work. 2008;53(3):286–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Siriwardhana C, Adikari A, Bortel T, McCrone P, Sumathipala A. An intervention to improve mental health care for conflict-affected forced migrants in low-resource primary care settings: a WHO MhGAP-based pilot study in Sri Lanka (COM-GAP study). Trials [Internet]. 2013; 14:[423 p.]. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/844/CN-01119844/frame.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Sinha S, David S, Gerdin M, Roy N. Vulnerabilities of Local Healthcare Providers in Complex Emergencies: Findings from the Manipur Micro-level Insurgency Database 2008–2009. PLoS Currents. 2013;(APR 2013) (no pagination)(ecurrents.dis.397bcdc6602b84f9677fe49ee283def7). . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Singh JA, DePellegrin TL. Images of war and medical ethics: physicians should not permit filming of their patients without consent. BMJ: British Medical Journal (International Edition). 2003;326(7393):774–5. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20030613. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Simunovic VJ. Health care in Bosnia and Herzegovina before, during, and after 1992–1995 war: a personal testimony. Conflict & Health [Electronic Resource]. 2007;1:7 10.1186/1752-1505-1-7 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Ghaleb S, Mukwege DM, Roberts R, Sulkowicz KJ, Vlassov VV. Protect Syria's doctors: an open letter to world leaders. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lancet; 2016. p. 1056–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Gilbert M. Protect health personnel in war zones!. [Norwegian] Beskytt helsepersonell i krigssoner! Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening. 2002;122(9):892 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Gluncic V, Pulanic D, Prka M, Marusic A, Marusic M. Curricular and extracurricular activities of medical students during war, Zagreb University School of Medicine, 1991–1995. Academic Medicine. 2001;76(1):82–7. 10.1097/00001888-200101000-00022 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Gold S. Caring for Gaza's victims of war. Nursing Standard. 2009;23(26):64–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20090417. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Goldberger JJ, Popp RL, Zipes DP. Israel-Gaza conflict. The Lancet. 2014;384(9943):577–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Goniewicz K, Goniewicz M, Pawlowski W. [Protection of medical personnel in contemporary armed conflicts]. Wiadomosci Lekarskie. 2016;69(2 Pt 2):280–4. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Gordon JS. Healing the wounds of war: Gaza Diary. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2006;12(1):18–21. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Gulland A. Attacks on health workers in conflict areas should be documented for advocacy purposes, conference hears. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;347 (no pagination)(f7259). . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Gulland A. Doctors urge Syrian government to allow them access to patients. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;347:f5698 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Gulland A. Medical students perform operations in Syria's depleted health system. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346 (no pagination)(f3107). . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Gulland A. WHO condemns attacks on healthcare workers in Yemen. BMJ (Online). 2015;350 (no pagination)(h2914). . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187.Haar RJ, Footer KH, Singh S, Sherman SG, Branchini C, Sclar J, et al. Measurement of attacks and interferences with health care in conflict: validation of an incident reporting tool for attacks on and interferences with health care in eastern Burma. Conflict & Health [Electronic Resource]. 2014;8(1):23 10.1186/1752-1505-8-23 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188.Haber Y, Palgi Y, Hamama-Raz Y, Shrira A, Ben-Ezra M. Predictors of Professional Quality of Life among Physicians in a Conflict Setting: The Role of Risk and Protective Factors. Israel Journal of Psychiatry & Related Sciences. 2013;50(3):174–80. Language: English. Entry Date: 10.1038/ki.2009.504 Revision Date: 20150923. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189.Hagopian A, Ratevosian J, Deriel E. Gathering in groups: Peace advocacy in health professional associations. Academic Medicine. 2009;84(11):1485 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190.Hallam R. Response to Syria's health crisis. The Lancet. 2013;382(9893):679–80. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191.Hameed Y. Dispatch from the medical front: A doctor and a grenade. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2009;181(3–4):E40 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192.Hampton T. Health care under attack in Syrian conflict. JAMA. 2013;310(5):465–6. 10.1001/jama.2013.69374 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193.Hathout L. The right to practice medicine without repercussions: ethical issues in times of political strife. Philosophy, ethics, and humanities in medicine: PEHM. 2012;7:11 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194.O’Connor K. Nursing Ethics and the 21st-Century Armed Conflict. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2017;28(1):6–14. 10.1177/1043659615620657 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20161208. Revision Date: 20161216. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Core Nursing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195.O'Brien DP, Mills C, Hamel C, Ford N, Pottie K. Universal access: the benefits and challenges in bringing integrated HIV care to isolated and conflict affected populations in the Republic of Congo. Conflict & Health [Electronic Resource]. 2009;3:1 10.1186/1752-1505-3-1 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196.O'Brien E. Bahrain: continuing imprisonment of doctors. Lancet. 2011;378(9798):1203–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61353-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197.Oulton JA. Inside view. Armed conflict: consequences and challenges for nurses. International Nursing Review. 2003;50(2):72–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20030725. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Continental Europe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198.Simetka O, Reilley B, Joseph M, Collie M, Leidinger J. Obstetrics during Civil War: six months on a maternity ward in Mallavi, northern Sri Lanka. Medicine, conflict, and survival. 2002;18(3):258–70. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199.Sidel VW, Levy BS. Commentary: Guard against war: An expanded role for public health. European Journal of Public Health. 2006;16(3):232 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200.Physicians Sibbald B., health facilities targeted in war-torn Syria. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2013;185(9):755–6. 10.1503/cmaj.109-4492 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20130927. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. Journal Subset: Biomedical. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201.Shetty P. Protecting health-care workers in the firing line. Lancet. 2013;382(9909):e41–2. 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62627-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202.Sheik M, Gutierrez MI, Bolton P, Spiegel P, Thieren M, Burnham G. Deaths among humanitarian workers. British Medical Journal. 2000;321(7254):166–8. 10.1111/1346-8138.14697 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203.Sheather J. The Sri Lankan doctors and the challenge for medical leadership. Indian journal of medical ethics. 2009;6(4):179–81. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204.Sharony Z, Eldor L, Klein Y, Ramon Y, Rissin Y, Berger Y, et al. The role of the plastic surgeon in dealing with soft tissue injuries: Experience from the second israel-lebanon war, 2006. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2009;62(1):70–4. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205.Sharma GK, Osti B, Sharma B. Physicians persecuted for ethical practice in Nepal. Lancet. 2002;359(9316):1519 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 206.Shanks L, Schull MJ. Rape in war: The humanitarian response. Cmaj. 2000;163(9):1152–6. 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.11.1171 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 207.Shamia NA, Thabet AAM, Vostanis P. Exposure to war traumatic experiences, post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth among nurses in Gaza. Journal of Psychiatric & Mental Health Nursing. 2015;22(10):749–55. 10.1111/jpm.12264 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20151218. Revision Date: 20161130. Publication Type: Article. Journal Subset: Core Nursing. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 208.Shamia NA, Mousa Thabet AA, Vostanis P. 'Agencies need to prepare staff for trauma of war zone work'. Nursing Times. 2014;110(42):11–. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20141030. Revision Date: 20150712. Publication Type: Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- 209.Shamai M. Using social constructionist thinking in training social workers living and working under threat of political violence. Social Work. 2003;48(4):545–55. sw/48.4.545. . Language: English. Entry Date: 20050425. Revision Date: 20150820. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 210.Serle J, Fleck F. Keeping health workers and facilities safe in war. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2012;90(1):8–9. 10.2471/BLT.12.030112 . Language: English. Entry Date: 20120221. Revision Date: 20150711. Publication Type: Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 211.Hawkes N. Attacks on doctors rise as rules of conduct in conflict zones are abandoned. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2012;344:e2973 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]