Abstract

Background:

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE), can give rise to long-term mental and physical health consequences as well as additional stressors later in the life course. This study aims to examine differing profiles of trajectories of adversity over the life course and investigate their association with socioeconomic and health outcomes.

Methods:

We used population representative data from the Washington State 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey (n = 7,953). Six ACE items were paired with six Adverse Adulthood Experience (AAE) items in respondents’ adulthood that parallel the ACE (e.g. physical abuse in childhood and physical victimization in adulthood). We applied latent class analysis to identify distinct trajectories of adversity; then tested for differences across trajectories in terms of demographic, socioeconomic, and health measures.

Results:

Six latent classes were identified: individuals with high AAE: (1. Consistently High, 2. Substance Abuse and Incarceration, 3. Adult Interpersonal Victimization) and individuals with low AAE (4. Repeat Sexual Victimization, 5. High to Low, and 6. Consistently Low). The Consistently High group had the highest prevalence of ACE and AAE and fared poorly across wide ranging outcomes. Other groups displayed specific patterns of ACE and AAE exposures (including salient subgroups such as those with incarceration exposure) as well as differences in demographic characteristics, illustrating disparities.

Conclusions:

Subgroup analyses such as this are complementary to population generalized findings. Understanding differences in life course patterns of adversity can shed light on interventions in earlier life and better target service provision to promote health and well-being.

Keywords: Adverse Childhood Experiences, life course, health, well-being, latent class analysis, stress

Introduction

The long-term health consequences of adversity in childhood have a robust and growing evidence base. Adult physical health outcomes including asthma, general health status, cardiovascular disease and mortality (Exley, Norman, & Hyland, 2015; Kelly-Irving et al., 2013; Su, Jimenez, Roberts, & Loucks, 2015) as well as physiological markers indicative of several complex diseases such as telomere length, inflammatory markers and DNA methylation are linked to adverse childhood experiences (ACE) (Mehta et al., 2013; O’Donovan et al., 2011; Slopen, Kubzansky, McLaughlin, & Koenen, 2013). Substantial evidence also indicates that ACE negatively impact mental health outcomes such as depression and anxiety (Green et al., 2010; Lindert et al., 2014; Nurius, Green, Logan-Greene, & Borja, 2015; Pearlin, Schieman, Fazio, & Meersman, 2005). In addition, ACE have been associated with intimate partner violence in adulthood (Montalvo-Liendo et al., 2015), as well as other social and psychological problems such as substance abuse, homelessness, criminal behavior and lower educational and occupational attainment at various points over the life course (Cutuli & Herbers, 2014; Giovanelli, Reynolds, Mondi, & Ou, 2016; Mersky, Topitzes, & Reynolds, 2013; Minh et al., 2013; Oppenheimer, Nurius, & Green, 2016). Further compounding the stress of ACE, those who are embedded within particularly stressful current day contexts such as poverty, household dysfunction, and system involvement also tend to have worse outcomes (Logan-Greene, Kim, & Nurius, 2016; Mersky et al., 2013; Rebbe, Nurius, Courtney, & Ahrens, 2018; Zielinski, 2009).

Early life stressors, such as ACE, can give rise to additional stressors later in the life course, a concept referred to as stress proliferation (Pearlin, 2010; Pearlin et al., 2005). Chronic and repeated stressors, that is, cumulative stress is thought to have an effect on several physiological systems as described by the concept of allostatic load (McEwen & Seeman, 1999). The life course perspective is arguably the best way to understand the health impacts of cumulative stress, as it provides a theoretical framework from which to understand the impact of ACE later in life. Specifically we use the life course health development theory to inform our work (Halfon et al., 2014). It posits that (1) risks and resiliencies throughout the life span help shape health and well-being, (2) adapting to adversity (via negative or positive coping behaviors) is important for survival and (3) timing of adversity (whether in a critical or sensitive period) may also help explain later life health.

Although much research has focused on the broad spectrum of ACE, less attention has been paid to understanding how these adversities are distributed over the life course and across the population (Edwards et al., 2005; Felitti, 2009; Merrick, Ford, Ports, & Guinn, 2018;). Measuring and understanding patterns of adversities that contribute to long-term health consequences can help design interventions in early life to buffer the effects of both early life and future adversities. Furthermore, evaluating adulthood adversity provides opportunities for further intervention and service provision specifically for those seeking assistance from primary care, human services and safety net providers. Many people only start to deal with the negative consequences of ACE later in life when clinical evidence begins to manifest and negative health outcomes arise. Regardless of when service providers encounter individuals with ACE, services or interventions for this population hold strong potential for lasting benefits to improve lives.

In this study we identify life course trajectories of adversity using latent class analysis (LCA). The use of LCA, a person-oriented analytic approach, differs from variable oriented techniques such as traditional regression modelling which focus on specific variables of interest averaged across a whole sample. Variable oriented approaches are useful in highlighting the overall impact of ACE on population health, but do not allow for the identification of population subgroups. Examining the heterogeneity of adverse experiences within populations can highlight the need to tailor individual and family treatment and support to the specific context at hand. Furthermore, understanding population heterogeneity allows us to better understand why some individuals with ACE do not go on to suffer the same negative health consequences as others. Many researchers have called for a more extensive look at resilience and coping strategies that buffer the ill effects of ACE and cumulative stress (Leitch, 2017; Traub & Boynton-Jarrett, 2017). Thus, person-oriented analytic findings do not stand in opposition to findings established through traditional methods, but rather address complementary questions aimed at understanding meaningful variations across the life course that can help predict risk or resilience.

In this study we create trajectories of adversity over the life course by identifying adversities in adulthood that echo those in childhood. We then describe differences in current socioeconomic resources and health based on the trajectories of adversity we identified. We hypothesized that heterogeneous patterns would be found, reflecting differing forms of adversity rather than just differences in level of adversity alone (e.g., low, medium, high adversity), suggesting a need for differential treatment and intervention approaches. We theorized that differing patterns of adversity would demonstrate that some adversities may co-occur. Additionally, we expect patterns of adversity to reflect social or economic resources that individuals can access to protect against later life adversity and which service providers may be able to draw upon for supportive and educational interventions.

Methods

Sample

The 2011 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) for Washington State was used for this study. The BRFSS is a cross-sectional, random-digit-dial population-based telephone survey conducted by the Washington State Department of Health in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Study participants were non-institutionalized English or Spanish speaking adults, aged 18 years or older. Most participants lived in a household with a working landline telephone; however, a small number of participants were selected and responding via cell phone. BRFSS provided sampling weights were not used in this analysis.

Measures

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE):

Respondents were asked if before the age of 18 anyone in their household experienced any of the following adverse experiences: serious mental illness, substance abuse (which combined alcohol abuse and drug abuse), incarceration, parental divorce or separation, physical abuse at home by parent or adult or if the respondent was subject to sexual abuse (which combined three items: being touched sexually, touching someone sexually, forced to have sex by someone 5 years older or an adult) (Bynum et al., 2010). The combination of various items (e.g. alcohol and drug abuse constituted substance abuse) resulted in a total of six ACE. Items pertaining to verbal abuse and witnessing domestic violence were not used as there were no equivalent items pertaining to adulthood experiences, which was the basis of our analytic strategy to present life course trajectories. For this study we used a cumulative ACE score only for descriptive analysis. The items were summed (no = 0, yes = 1) to create a six point ACE score where one point is given for each of the adversities listed above. In order to create trajectories using LCA, each of these six individual ACE were used as separate indicators.

Adverse Adulthood Experiences (AAE) are six adverse experiences in respondents’ adulthood that parallel six of the original ACE: serious mental illness measured by the Kessler-6 scale (nervous, hopeless, restless, depressed, effortless, worthless), substance abuse (binge drinking/drug abuse/marijuana use), incarceration, divorce/separation/widowhood, physical victimization (slap, hit, kick, punch, beat by intimate partner), or sexual victimization (attempted or completed forced sex). Similar to ACE, a cumulative AAE score was used for descriptive analysis and each individual AAE indicator was used to create trajectories.

Demographic characteristics used in this study were age (range: 18–97), gender (0 = male, 1 = female), race/ethnicity (white, black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander and mixed or other race/ethnicity), 1 = veteran) and sexual orientation (0 = heterosexual, 1 = gay/lesbian, 2 = bisexual).

Conceptually similar variables from the WA state BRFSS were grouped into domains related to SES resources and health as described below.

Socioeconomic Resources

Socioeconomic Status included (1) annual household income (8-level ordinal scale: $0 to ≥$10,000; $10,000 to ≥$15,000; $15,000 to ≥$20,000; $20,000 to ≥$25,000; $25,000 to ≥$35,000; $35,000 to ≥$50,000; $50,000 to ≥$75,000; and $75,000 or more; M = 6.02, SD = 1.90), (2) highest education completed (4-level ordinal scale: not high school graduate, high school graduate, some college, college graduate; M = 3.07, SD = 0.91), and (3) inability to work (0 = employed, self-employed, homemaker, student, and retiree, 1 = unemployed or unable to work due to other reasons; M = 0.12, SD = 0.32).

Food and Housing Insecurity included (1) poor nutrition (not affording nourishing food: 0 = never to 4 = always;M = 0.45, SD = 0.91), (2) food insecurity (sum of five indicators that over the past 12 months within respondent’s household sometimes or often food didn’t last, ate unbalanced meals, cut meal size or skipped meal, ate less than needed, and was left hungry; M = 0.34, SD = 1.04), (3) residential insecurity (lacked ability to pay rent/mortgage: 0 = never to 4 = always; M = 0.78, SD = 1.13), and (4) homelessness (sum of “yes” responses to residing in a transitional housing, a shelter, or voucher lodging and/or a vehicle, abandoned building, or public outdoors (range: 0–2, M = 0.02, SD = 0.15).

Health Care Access included (1) healthcare coverage (0 = none, 1 = private or public insurance; M = 0.90, SD = 0.30), (2) medical cost barrier (0 = none, 1 = needed see a doctor but not able because of cost; M = 0.11, SD = 0.31), (3) routine checkup (M = 3.40, SD = 1.00), and (4) dental checkup (M = 3.43, SD = 1.02) (the latter two assessed as: 0 = never, 1= 5 or more years, 2 = within the past 5 years, 3 = within the past 2 years, and 4 = within the past year).

Health Behaviors and Health

Health behaviors included (1) tobacco use (0 = never, 1 = past or current; M = 0.46, SD = 0.50), (2) body mass index (0 = neither overweight or obese, 1 = overweight, 2 = obese, using self-reported height and weight to calculate BMI; M = 0.92, SD = 0.79), (3) number of minutes per week for total physical exercise, such as calisthenics, golf, or walking (range: 08400; M = 499, SD = 669), and (4) use of seatbelts (0 = never, 1= seldom, 2 = sometimes, 3 = nearly always, and 4 = always; M = 3.91, SD = 0.43).

Disability included (1) serious injury in workplace (M = 0.05, SD = 0.22), (2) limited activity due to physical, mental, or emotional problems (M = 0.35, SD = 0.48), and (3) health problems with special equipment (M = 0.11, SD = 0.31) (three indicators above measured as “yes/no”).

Physical Health was comprised of: (1) chronic illness index (sum of “yes” responses to 11 self-reported diagnoses (heart attack, angina, stroke, cancer, diabetes, arthritis, asthma, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and kidney disease) (range: 0–11, M = 1.96, SD = 1.63), (2) self-reported health status (Likert-type scale: poor = 0 to excellent = 4; M = 2.49, SD = 1.07), (3) number of days per month physical health was not good (M = 4.28, SD = 8.73), and (4) number of days per month that poor health disrupts usual activities (M = 5.30, SD = 9.25) (the latter two ranged: 0–30).

Mental Health included (1) number of days per month mental health was not good (M = 3.07, SD = 7.30), (2) number of days per month that emotional problem disrupts doing work (M = 0.86, SD = 4.04) (the above two ranged: 0–30 days), and (3) receiving medicine or treatment for mental disorder (0 = no, 1 = yes; M = 0.14, SD = 0.35).

Statistical Analysis

To examine the underlying trajectories of adversity from childhood to adulthood, an LCA was conducted. LCA posits that relationships among observed variables (here, a total of 12 parallel adversity items in both childhood and adulthood) are explained by estimable latent classes and can thus identify and test support for underlying configurations of adversity (Oliver, Kretschmer, & Maughan, 2014). The classes identified by LCA are mutually exclusive and exhaustive and are based on similarities in respondent’s answers to ACE and AAE questions. All respondents with no missing data on the six ACE and comparable six indicators of AAE were used for this analysis. This yields a dataset of adults aged 18 years and older as the unit of analysis (n = 7,953). The resulting classes represent the underlying configurations of adversity across the life course.

LCA using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was conducted in Mplus v7.3. Several model fit statistics were examined in order to determine the optimal number of classes: 1) Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), a commonly used index that applies a penalty based on the number of parameters, with smaller values suggesting a better fit (Muthén & Muthén, 2007), 2) Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) adjusted likelihood ratio test that tests the superiority of a K class model against K-1 class model; where p-values less than 0.05 indicate better fit and 3) relative entropy, which is rescaled by Mplus so that values near one indicate higher certainty in classification and values near zero indicate lower certainty (Ford, Grasso, Hawke, & Chapman, 2013). In addition, substantive knowledge and sample size considerations were taken into account when deciding on the final number of classes.

In order to examine health among the different adversity trajectory groups (LCA classes), we compared means of each indicator using a series of Wald tests (significance level of p < 0.05). Means were calculated in Mplus using the ‘BCH’ command, a feature, which allows for a 3-step approach to incorporate additional variables into the LCA (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014). An overall Wald test indicates if the classes significantly differed from each other on the indicator of interest and pairwise Wald tests indicated which of two specific trajectory groups differed significantly from each other. Given the categorical nature of LCA, Wald tests are an appropriate statistical approach to compare covariates across different latent classes.

Results

Latent Class Analysis

We chose a six-class solution to best describe trajectories of life course adversity. Although the BIC statistic was slightly lower for the 5-class solution, we believed that the additional group created in the 6-class solution was a meaningful addition to the experiences of adversity. Entropy, another measure of fit, was only slightly higher for the 7-class solution compared to the 6-class (0.716 vs 0.712 respectively). In this case, the additional class did not contribute meaningfully to our understanding of trajectories of adversity. The LMR statistic was significant (102.1, p<0.05) indicating an improvement in fit comparing the six- to the five-class solution, but no improvement compared to the seven-class solution (p = 0.17). Fit statistics for the 1 to 7 class solutions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Fit statistics for 1–7 class solutions

| BIC | LMR | LMR p-value | Entropy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Class | 78401.799 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2-Class | 73302.678 | 5171.483 | <.001 | 0.739 |

| 3-Class | 72797.150 | 616.925 | <.001 | 0.716 |

| 4-Class | 72556.808 | 353.991 | <.001 | 0.678 |

| 5-Class | 72535.652 | 136.668 | <.01 | 0.704 |

| 6-Class | 72549.355 | 102.105 | <.05 | 0.712 |

| 7-Class | 72591.187 | 74.216 | .17 | 0.716 |

Note: BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; LMR, Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test.

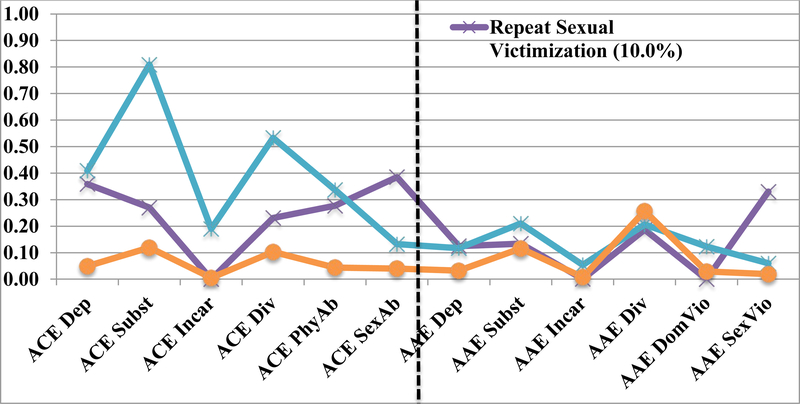

Given the six-class solution, we grouped our trajectory classes into two groups; the first distinguishing individuals with high AAE: 1) Consistently High, 2) Substance Abuse and Incarceration, 3) Adult Interpersonal Victimization and the second composed of individuals with low AAE: 4) Repeat Sexual Victimization, 5) High to Low, and 6) Consistently Low. The LCA groupings differed in their adversity configurations as highlighted in Figures 1 to 3.

Figure 1.

Response Probabilities of Six Latent Classes

Note: ACE Dep=Depression, ACE Subst=Substance Abuse, ACE Incar=Incarceration, ACE Div=Divorce/Separation, ACE PhyAb=Physical Abuse, ACE SexAb=Sexual Abuse. AAE Dep=Adult Depression, AAE Subst=Adult Substance Abuse, AAE Incar=Adult Incarceration, AAE Div=Adult Divorce/Separation, AAE DomVio=Adult Domestic Violence, AAE SexVio=Adult Sexual Violence.

Figure 3.

Response Probabilities of Latent Classes with Low AAE

Note: ACE Dep=Depression, ACE Subst=Substance Abuse, ACE Incar=Incarceration, ACE Div=Divorce/Separation, ACE PhyAb=Physical Abuse, ACE SexAb=Sexual Abuse. AAE Dep=Adult Depression, AAE Subst=Adult Substance Abuse, AAE Incar=Adult Incarceration, AAE Div=Adult Divorce/Separation, AAE DomVio=Adult Domestic Violence, AAE SexVio=Adult Sexual Violence.

Adversity Profiles

As shown in Figures 1 through 3 and Table 2, the adversity profiles of these groups differ significantly. The Consistently High group, which comprises about 7% of the study population, had the highest prevalence of ACE on all six individual adversities, with 91.4% reporting ≥ 3 ACE. They also reported the highest levels of AAE with 57.4% of the group reporting ≥ 3 AAE. They had the highest probabilities of both childhood physical and sexual abuse and the highest probability of adult depression relative to other classes. The Substance Abuse and Incarceration group (the smallest group at 2.2% of the study population) reported relatively high levels of incarceration and childhood divorce but a smaller proportion reported ≥ 3 ACE (approximately 16%). In terms of AAE, they had the highest prevalence of adult substance abuse and incarceration with 48.3% reporting ≥ 3 AAE. The Adult Interpersonal Victimization group (6.8% of the study population) does not report a high number of ACE, only 4% report ≥3 ACE, but a sizable proportion of the group reported one of the more severe adversities, sexual abuse in childhood (28%). In adulthood, however, this group reported high levels of physical and sexual abuse and divorce with almost 40% reporting ≥ 3 AAE.

Table 2:

Mean and Standard Deviation of ACE and AAE score and Percent of ACE, overall and across six Latent Class Groups

| Total (N=7953) | Consistently High (N=509) | Substance Abuse & Incarceration (N=145) | Adult Interpersonal Victimization (N=483) | Repeat Sexual Victimization (N=569) | High to Low (N=1,064) | Consistently Low (N=5,183) | F test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE mean score (SD) | 1.05 (1.29) | 3.81 (1.00) | 1.45 (1.07) | 1.05 (0.86) | 1.91 (0.79) | 2.66 (0.87) | 0.34 (0.51) | F(5, 7902)=4343.67*** |

| AAE mean score (SD) | 0.84 (1.02) | 2.81 (1.12) | 2.58 (0.98) | 2.37 (0.76) | 0.98 (0.81) | 0.73 (0.78) | 0.46 (0.60) | F(5, 7902)=1739.72*** |

| % ≤ 2 ACE | 85.55 | 8.65 | 84.14 | 96.6 | 79.26 | 51.31 | 100 | NA |

| % ≥ 3 ACE | 14.5 | 91.4 | 15.9 | 3.9 | 20.7 | 48.7 | 0 | |

| % ≤ 2 AAE | 92.22 | 42.64 | 51.73 | 60.04 | 95.78 | 98.21 | 99.67 | NA |

| % ≥ 3 AAE | 7.78 | 57.4 | 48.28 | 39.97 | 4.22 | 1.78 | 0.33 |

ACE: Adverse childhood experiences, AAE: Adverse adulthood experiences

The mean AAE and ACE scores were created by summing the responses to 6 adversity items, scale between 0 – 6

The sample sizes presented in the F test column do not equal the total sample size (7952) because some participants had missing data on ACE items.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Among the 3 groups with lower AAE, the Repeat Sexual Victimization group (10% of study population) had the 2nd highest prevalence of childhood sexual abuse (39%, only the Consistently High group reported a higher prevalence, 72%), and moderate levels of physical abuse in childhood (prevalence of 28%) and sexual violence in adulthood (prevalence of 33%). The High to Low group (13.6% of population) reported high prevalence of all ACE except sexual abuse, with a particularly high prevalence of parental substance abuse (81%) and nearly half the group reporting ≥ 3 ACE. In adulthood this pattern is reversed for this group with the profile of AAE being comparable to the other low AAE groups. Lastly, the Consistently Low group makes up the majority of the study population, 60.7%, and has low levels of ACE and AAE relative to the other groups. Among this group, approximately 68% report zero ACE and 59% report zero AAE.

Demographic Characteristics of the Trajectories

Demographic characteristics of the total population and the six latent classes are shown in Table 3; the overall average age of the sample was 58.0 years (SD = 15.7). Demographic characteristics varied significantly across the 6 trajectory groups. The Consistently High group was characterized by more females (85.3%) and younger respondents (between 18 – 54 years old), identifying as sexual minorities (9%), and more Native American and Mixed race respondents (9.8%) compared to the total population (4%). The Substance Abuse and Incarceration group had a substantially greater proportion of males, veterans, younger ages, and Latino, Black and Mixed race respondents. Females were also more prevalent in the Adult Interpersonal Victimization as were respondents 45 years and older. Among the Repeat Sexual Victimization group, there were more females and more civilians but otherwise this group resembled the overall sample. The Consistently Low group was, by contrast, more balanced by sex, with a greater prevalence of older, White, heterosexual respondents. They resembled the total sample most closely as they were the largest of the six trajectory groups.

Table 3:

Percent Distribution of Demographic Characteristics of Total Population and six Latent Class Groups

| Total (n=7953) | Consistently High (N=509) | Substance Abuse & Incarceration (N=145) | Adult Interpersonal Victimization (N=483) | Repeat Sexual Victimization (N=569) | High to Low (N=1,064) | Consistently Low (N=5,183) | X2 Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–34 | 8.42 | 10.26 | 14.48 | 3.96 | 6.73 | 15.60 | 7.19 | X2 (15, N=7860)=418.52*** |

| 35–44 | 11.40 | 17.16 | 16.55 | 8.54 | 14.34 | 13.23 | 10.24 | ||

| 45–64 | 44.90 | 59.17 | 55.17 | 48.54 | 54.69 | 49.43 | 40.82 | ||

| 65 or older | 35.28 | 13.41 | 13.79 | 38.96 | 24.25 | 21.74 | 41.74 | ||

| Gender | Male | 40.71 | 14.73 | 87.59 | 15.32 | 22.32 | 46.71 | 45.13 | X2 (5, N=7908)=540.56*** |

| Female | 59.29 | 85.27 | 12.41 | 84.68 | 77.68 | 53.29 | 54.87 | ||

| Race | White | 88.17 | 84.81 | 83.33 | 87.71 | 89.07 | 85.85 | 89.06 | X2 (30, N=7850)= 167.38*** |

| Latinx | 4.62 | 3.55 | 5.56 | 3.75 | 4.06 | 6.46 | 4.47 | ||

| Black | 1.10 | 1.38 | 3.47 | 1.88 | 0.88 | 1.71 | 0.82 | ||

| Asian | 1.95 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 1.23 | 0.38 | 2.73 | ||

| Native American | 0.93 | 2.76 | 1.39 | 1.25 | 1.06 | 1.90 | 0.49 | ||

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.12 | ||

| Mixed race | 3.07 | 7.10 | 6.25 | 4.58 | 3.53 | 3.42 | 2.31 | ||

| Sexual Orientation | Heterosexual | 97.70 | 91.00 | 99.30 | 97.67 | 97.50 | 97.79 | 98.33 | X2 (10, N=7691)= 166.68*** |

| Homosexual | 1.60 | 4.00 | 0.70 | 1.69 | 1.79 | 1.82 | 1.31 | ||

| Bisexual | 0.70 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.36 | ||

| Veteran Status | Not veteran | 84.55 | 94.96 | 77.24 | 92.75 | 90.33 | 82.99 | 82.67 | X2 (5, N=7904)= 101.25*** |

| Veteran | 15.45 | 5.31 | 22.76 | 7.25 | 9.67 | 17.01 | 17.33 |

The sample sizes presented in the X2 column do not equal the total sample size (7952) because some participants had missing data on demographic characteristics.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Socioeconomic Resources and Health

Tables 4 and 5 present the results of the Wald tests and indicate that overall the means for all the indicators were different from each other. That is, all the SES and health indicators listed in tables 4 and 5 are strongly associated with the 6 identified classes. We also evaluated differences in means between each of the pairs of trajectory groups (i.e. Consistently High vs Substance Abuse and Incarceration, Consistently High vs Adult Interpersonal Victimization, etc.) resulting in a total of 15 possible comparisons.

Table 4:

Means (Standard Errors) and Overall Wald statistics for Each Latent Class Group by Socioeconomic and Resource Domains+

| Consistently High (1) | Substance Abuse & Incarceration (2) | Adult Interpersonal Victimization (3) | Repeat Sexual Victimization (4) | High to Low (5) | Consistently Low (6) | Wald statistic*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic Status | |||||||

| Income b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,j,k,l,m,n | 4.46 (0.13) | 4.43 (0.28) | 5.24 (0.14) | 6.89 (0.14) | 6.16 (0.09) | 6.17 (0.03) | 302.68 |

| Education a,b,c,e,f,g,h,i,j,k,m,n,o | 2.86 (0.05) | 2.36 (0.11) | 3.08 (0.06) | 3.42 (0.06) | 2.87 (0.04) | 3.11 (0.02) | 131.36 |

| Inability to work b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,l,n,o | 0.45 (0.03) | 0.5 (0.06) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.03) | 0.14 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.01) | 308.67 |

| Food/Housing Insecurity | |||||||

| Poor nutrition a,b,c,d,e,i,l,n,o | 1.72 (0.12) | 0.86 (0.20) | 0.66 (0.09) | 0.45 (0.10) | 0.62 (0.07) | 0.24 (0.02) | 248.50 |

| Food insecurity a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,j,l,m,o | 1.80 (0.11) | 1.07 (0.20) | 0.42 (0.08) | 0.20 (0.07) | 0.43 (0.06) | 0.14 (0.01) | 331.64 |

| Residential insecurity b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,l,n,o | 2.15 (0.13) | 1.66 (0.29) | 0.97 (0.10) | 0.83 (0.12) | 1.02 (0.08) | 0.52 (0.02) | 256.15 |

| Homelessness b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,o | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.20 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 106.01 |

| Health Care Access | |||||||

| Healthcare coverage a,b,c,e,f,g,h,i,m,o | 0.82 (0.02) | 0.60 (0.06) | 0.91 (0.02) | 0.94 (0.02) | 0.86 (0.02) | 0.93 (0.01) | 80.07 |

| Medical cost barrier b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,l,n,o | 0.37 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.05) | 0.12 (0.02) | 0.14 (0.03) | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.01) | 223.02 |

| Routine checkup b,c,d,e,f,g,i,k,m,o | 3.04 (0.07) | 3.03 (0.14) | 3.49 (0.06) | 3.50 (0.07) | 3.29 (0.05) | 3.46 (0.02) | 56.49 |

| Dental checkup a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,j,m,o | 2.94 (0.07) | 2.59 (0.15) | 3.41 (0.07) | 3.62 (0.07) | 3.38 (0.05) | 3.50 (0.02) | 121.11 |

Higher values indicate higher income, more education, receiving healthcare coverage, routine checkups, and dental checkups. For other variables higher values are worse.

All Wald statistic p-value <.001

Significant difference at .05 level between:

1st (Consistently High) and 2nd (Substance Abuse and Incarceration) groups;

1st and 3rd groups.;

1st and 4th groups;

1st and 5th groups;

1st and 6th groups;

2nd and 3rd groups;

2nd and 4th groups;

2nd and 5th groups;

2nd and 6th groups;

3rd and 4th groups;

3rd and 5th groups;

3rd and 6th groups;

4th and 5th groups;

4th and 6th groups;

5th and 6th groups.

Table 5:

Means (Standard Errors) and Overall Wald statistics for Each Latent Class Group by Health and Health Behaviors*

| Consistently High (1) | Substance Abuse & Incarceration (2) | Adult Interpersonal Victimization (3) | Repeat Sexual Victimization (4) | High to Low (5) | Consistently Low (6) | Wald statistic** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Behaviors | |||||||

| Tobacco use a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,j,l,m,o | 0.76 (0.03) | 1.02 (0.05) | 0.52 (0.03) | 0.40 (0.04) | 0.54 (0.02) | 0.39 (0.01) | 440.95 |

| Body mass index b,d,e,i,n,o | 1.13 (0.05) | 1.12 (0.09) | 0.96 (0.05) | 1.02 (0.06) | 0.96 (0.04) | 0.86 (0.01) | 48.80 |

| No. minutes/week for total physical exercisec,j,n | 507.79 (42.44) | 455.82 (77.89) | 566.99 (52.47) | 362.41 (42.52) | 450.50 (34.55) | 524.45 (12.91) | 17.35 |

| Use of seatbelts in car b,c,e,f,g,i,k,m,n,o | 3.84 (0.03) | 3.72 (0.08) | 3.94 (0.02) | 3.99 (0.02) | 3.87 (0.02) | 3.92 (0.01) | 29.32 |

| Disability | |||||||

| Serious injury c,d,e,g,i,j,l | 0.13 (0.03) | 0.14 (0.05) | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 22.29 |

| Limited activity b,c,d,e,g,h,i,k,l,m,n,o | 0.71 (0.03) | 0.61 (0.06) | 0.49 (0.03) | 0.46 (0.04) | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.27 (0.01) | 363.26 |

| Health problems with special equipment b,d,e,h,i,j,k,l | 0.27 (0.02) | 0.18 (0.04) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.09 (0.01) | 75.82 |

| Physical Health | |||||||

| Chronic illness index c,d,e,j,k,l | 2.55 (0.12) | 2.00 (0.26) | 2.30 (0.11) | 1.85 (0.12) | 1.95 (0.09) | 1.89 (0.03) | 46.44 |

| Self-reported health status b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i,j,l,m,o | 1.78 (0.07) | 1.81 (0.14) | 2.35 (0.07) | 2.64 (0.08) | 2.40 (0.05) | 2.61 (0.02) | 215.40 |

| No. days/month physically unhealthy b,c,d,e,f,h,i,l,m,n | 11.83 (0.70) | 8.96 (1.38) | 4.80 (0.60) | 5.97 (0.70) | 3.64 (0.41) | 3.09 (0.14) | 207.10 |

| No. days/month poor health disrupts usual activitiesa,b,c,d,e,h,i | 11.85 (0.67) | 7.70 (1.47) | 4.78 (0.74) | 5.49 (0.75) | 4.21 (0.56) | 3.95 (0.24) | 135.23 |

| Mental Health | |||||||

| No. days/month mentally unhealthya,b,c,d,e,i,l,n,o | 12.07 (0.66) | 6.39 (1.20) | 3.87 (0.53) | 3.94 (0.57) | 4.15 0.40) | 1.48 (0.10) | 400.33 |

| No. days/month to emotional problem disrupts doing work a,b,c,d,e,i,l,n,o | 5.90 (0.50) | 1.96 (0.70) | 0.95 (0.31) | 1.03 (0.33) | 1.01 (0.22) | 0.20 (0.05) | 199.14 |

| Receiving Rx/Tx for mental disorder a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,l,m,n,o | 0.50 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.20 (0.03) | 0.27 (0.03) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.01) | 381.02 |

Higher values indicate more time spent on physical exercise, use of seatbelts in car, better self-reported health status, and receiving treatment for mental disorder. For other variables higher values are worse.

All Wald statistic p-value <.01

Significant difference at .05 level between:

1st (Consistently High) and 2nd (Substance Abuse and Incarceration) groups;

1st and 3rd groups.;

1st and 4th groups;

1st and 5th groups;

1st and 6th groups;

2nd and 3rd groups;

2nd and 4th groups;

2nd and 5th groups;

2nd and 6th groups;

3rd and 4th groups;

3rd and 5th groups;

3rd and 6th groups;

4th and 5th groups;

4th and 6th groups;

5th and 6th groups.

A brief summary of the socioeconomic resources and health characteristics of each of the six trajectory groups follows.

Consistently High:

This group tends to fare poorly on socioeconomic resource domains. They report poor nutrition and food insecurity more than other groups, but are similar to the Substance Abuse and Incarceration group (another poor functioning group) on several of the other SES metrics (e.g. income, inability to work, residential insecurity, medical cost barriers). For physical health, they report the highest number of days that poor health disrupts their usual activity, but similar levels of poor self-reported health status, days of poor physical health, activity limitation and other disability measures and compared to the Substance Abuse and Incarceration group. In terms of mental health, they report the highest number of poor mental health days and emotional problems; but, also reported receiving treatment for mental health disorders at a higher rate than other groups.

Substance Abuse and Incarceration:

This group reports the lowest level of education relative to the other groups. In terms of access to care, this group reported the lowest level of health care coverage and fewer dental checkups compared to the other groups. They also exhibit higher tobacco use compared to the other groups, poor self-reported health status and a high number of poor physical health days. They also report significantly higher number of mentally unhealthy days but with comparatively fewer receiving mental health treatment.

Adult Interpersonal Victimization:

This group reported moderate levels of income, education and proportion unable to work. Their health status was poor on serious injury and chronic illness, similar to the two groups described above. Overall they had better health outcomes compared to the Consistently High and Substance Abuse and Incarceration groups but worse compared to the three groups with lower AAE.

Repeat Sexual Victimization:

This group has relatively a high SES resource profile, reporting the highest income and education level of any group. They report the highest level of education and income as well as good access to health care. As for health indicators they are moderate on some (e.g. activity limitation, days of poor physical and mental health) and better off on others (e.g. lower tobacco use, higher seat belt use, lower serious injury, higher self–rated health). They are among the higher proportion groups to have received mental health treatment.

High to Low:

This group also reported moderate levels of SES resources, with the exception of education and health care coverage, where they report one of the lowest levels (similar to Consistently High). Overall their health status is in the moderate range, not among the worse but not among the best either. Tobacco use, BMI, activity limitation and self-reported health status are at moderate levels.

Consistently Low:

Overall this group has among the best SES and health profiles compared to the other groups. Although they may not have the highest SES resource levels on all the indicators (e.g. income and education are higher among Repeat Sexual Victimization) many of the health status indicators are better than the other groups (e.g. days of poor mental and physical health, activity limitation and BMI).

Discussion

This paper provides a useful contribution to the literature by establishing informative differences in life course adversity trajectories among population representative adults. Moreover, groups with these differing profiles of adversity reflected significant differences across a range of adult health outcomes. Our a priori hypothesis, that heterogeneous patterns would be found, reflecting differing forms and levels of adversity, and that these patterns would reflect differences in health as well as social and economic resources, was confirmed.

Using LCA, we identified six latent class groups. Several groups display patterns of both childhood and adult adversity that reinforce disadvantage in current health and well-being. Specifically the Consistently High and Substance Abuse and Incarceration groups are worse off relative to the others. Although the Consistently High group appears to be receiving mental health services, it is unclear if their service provision is sufficient, as evidenced by the number of poor mental health days. Furthermore, this group could use improvements in access to care and physical health services given their high number of poor physical health days and disproportionate level of disability related outcomes. This suggests the importance of both physical and mental health providers assessing adversity histories to better serve clients and to connect them with beneficial resources.

On the systems level, better integration of physical and mental health services would benefit this population, as would early assessment of ACE that could identify risk factors before chronic conditions are clinically manifest, thus allowing greater opportunity for prevention and resilience. Furthermore,, it has been shown that the relatively small population with several mental and physical health conditions account for a larger percent of total healthcare expenditure (Buttorff, Ruder, & Bauman, 2017). In our study, this may be the Consistently High and Substance Abuse groups that could benefit from more intensive service provision -- that includes an individual’s social context – which could potentially result in reductions in health care costs.

It is also important to note that the Consistently High group has a larger proportion of sexual minorities, which further underscores disproportional exposure to adversity for this population (Austin, Herrick, & Proescholdbell, 2016) as well as the need for appropriate care. In addition, the pattern displayed by this group may reflect those especially vulnerable to intergenerational adversity, representing another opportunity where early intervention may help improve later life health and overall quality of life. Both the Consistently High and Substance Abuse and Incarceration groups are still relatively young and showing signs of impairment and ill health earlier than other groups. Intervening among these populations earlier in the life course could prevent premature morbidity and mortality.

The Substance Abuse and Incarceration group overall reports unfavorable status second only to Consistently High. This includes low income, education and employment indicators as well as the highest reported tobacco use, worse self-reported physical health, and less receipt of mental health treatment. A striking feature of this group is their high levels of food and residential insecurity and ever homeless as well as disproportionate representation by males and those of Black, Latino and Mixed Race heritage—reflective of incarceration disparities. This population would appear to benefit from additional and coordinated service provision, and in some cases transitional service supports (e.g., from incarceration or military service). Given the large population of veterans in this group, strengthening services within the Veterans Administration or elsewhere that veterans seek care or focusing attention on the development of new and effective interventions in this population may help alleviate some of the health burden and stress associated with their multiple stressors. WA has a sizeable population of veterans (about 600,000 or 8.5% of the population) further aligning our findings with the context of our state’s demographics (Census Bureau, 2018, March 8). Features of the Substance Abuse and Incarceration group suggest a marginalized population. One of the critiques of the ACE literature is that studies have been unable to identify marginalized groups because study populations have been largely white and middle class (Cronholm et al., 2015). By using an LCA approach our study was able to identify a potentially marginalized group. These results provide support for additional service provision and interventions aimed at this population.

Adult Interpersonal Victimization constituents are overly represented by those who have suffered from intimate partner violence (IPV) and/or sexual victimization. Research has shown that those suffering from sexual abuse in childhood are more likely to suffer from IPV and sexual revictimization as adults (Barnes, Noll, Putnam, & Trickett, 2009; Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012; Montalvo-Liendo et al., 2015). Clinicians working with adult IPV and sexual abuse victims may not be including assessment of early life adversity, which would provide potentially useful life course trauma information that has implications for treatment. Since sexual victimization may or may not be perpetrated by an intimate partner and may have long lasting mental and physical health consequences, this is an important area for discussion with a health or social service professional. This group has higher childhood sexual abuse and parental substance abuse and in terms of adulthood adversity, they have much higher rates of divorce, physical and sexual violence. Therefore we might conclude that current poor health profiles are being driven by childhood sexual abuse and reinforced through physical and sexual violence in adulthood.

Although the Repeat Sexual Victimization group has moderate health and comparatively high SES, it is notable that compared to the other low AAE groups they report the highest number of days physically unhealthy and days that health disrupts daily activities as well as higher rates of treatment for mental health. Although biomarker data are not available, it may be that early stress activated by child sexual abuse and parental substance abuse triggered biological dysregulation that are reflected in poorer health during adulthood. Other indicators do not seem to directly reflect the negative effects of adversity. Therefore, it may be that their financial resources, access to health care, and openness to mental health treatment as well as other resiliencies (that we are unable to capture) have provided some protection against broader socioeconomic and health behavior impairments.

The High to Low group has lower education, higher rates of food insecurity and smoking and poorer self-rated health compared to the other two low AAE groups. Their profile suggests that despite early childhood adversity they go on to have relatively few adult adversities. This could point to coping strategies and protective factors over the life course that has buffered negative health consequences. However, the low education and high tobacco use observed in this group also suggest the lasting impact of ACE on later life. Given the relatively large size of this group (second largest), understanding their coping and protective factors could help design prevention and resilience interventions that improve health.

The importance of interventions, resilience factors and prevention in reducing the negative impact of ACE on health throughout the life course cannot be understated. Cognitive behavior therapy has been shown to improve outcomes among those who have experienced ACE (Macdonald et al., 2016). An online intervention designed to help college students cope with adversity was especially effective among those with ACE and is an example of an intervention that addresses needs earlier in the life course (Ray, Arpan, Oehme, Perko, & Clark, 2019). For children, multicomponent interventions focused on parenting education, mental health counseling, referrals to services or social support can improve children’s behavioral and mental health problems (Marie-Mitchell & Kostolansky, 2019). In terms of resilience factors, one systematic review suggests that resilience factors at the individual, family and community level can benefit young people after exposure to ACE and that understanding how multiple resilience factors work together may help shed light on how resiliencies impact long term outcomes (Fritz, de Graaff, Caisley, van Harmelen, & Wilkinson, 2018). In addition, positive interpersonal experiences with family friends, school and the community may also buffer the negative mental health impact of ACE (Bethell, Jones, Gombojav, Linkenback, & Sege, 2019). Lastly, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have outlined a comprehensive set of strategies to prevent ACE, they include: strengthening economic resources for families, promoting norms that discourage violence; promoting a healthy early childhood; improving skills to handle stress and emotions among parents and youth; connecting youth to services; and improving primary care providers ability to identify and support patients with ACE and provide trauma-informed care (Merrick et al., 2019).

Putting Results in the Context of Theory

The life course health development theory (LCHD), as put forth by Halfon and colleagues (2014), is helpful in putting our findings into a theoretical context. Several tenants of LCHD help explain the trajectories we observed. First, many different risks and resiliencies throughout the life span are critical in shaping health and well-being. For example, we could theorize that the High to Low group had more protective factors in adulthood which could explain their better health status (relative to other groups), i.e. buffering resources in adulthood helps reduce the effects of ACE. In addition, we see in the High to Low group lower levels of cumulative stress in adulthood that could also be contributing to their improved health in later life. By contrast, the Consistently High group shows the opposite pattern: the accumulation of chronic stressors well into adulthood takes a toll on socioeconomic circumstances and health. The differing impacts of cumulative stress reinforce the idea that dose (e.g., number of ACE), duration (childhood and adulthood) and the combination of risk and protective factors during childhood and beyond are critical to understanding the differing outcomes among groups who face similar adversity in childhood.

Furthermore, the identification of physiological manifestation of ACE (i.e. via inflammation or other subclinical markers) that precede full blown disease may provide early-stage opportunities for intervention (Danese & McEwen, 2012; Slopen et al., 2013). In clinical settings, asking about one’s history of stress and adversity may help prevent or lessen the severity of future disease even in the presence of subclinical symptoms. For individuals with known childhood adversity, and particularly with beginning signs of adulthood challenges, examination for signs of subclinical symptoms could support more intentional interventions in preventing the development of future health and quality of life problems.

Beyond the specific risks and resiliencies people face, the ability to adapt in the face of adversity is a critical survival mechanism used by many over the course of human history. As shown in our results, even the worse off groups are exhibiting some adaptivity in the sense of responding to physiological dysregulations generated by stress exposure. Although the behaviors by some may not be health promoting, they are nevertheless examples of adaptive response. This is well outlined in the adaptive-calibration model originally developed by Del Giudice and colleagues and a prominent component of LCHD (Del Giudice, Ellis, & Shirtcliff, 2011; Halfon, Larson, Lu, Tullis, & Russ, 2014). This model specifies a developmental framework of neurobiological efforts by human systems to re-regulate their systems and functioning in the context of stress exposure. An illustration of adaptive response can be found in the Substance Abuse and Incarceration group, where they appear to use health-deleterious coping behaviors such as smoking and lack of care seeking behavior to deal with the challenges they face. As described in the LCHD, health improves when environmental conditions meet the needs of social or physiological systems but declines when they do not.

Lastly, although it is difficult to evaluate specific critical and sensitive periods given our data, the timing of childhood adversity may help explain poor health in adulthood. As illustrated by the life course approach and incorporated as a central tenant of the LCHD, identification of critical and sensitive periods may provide a robust explanation for the heterogeneity seen in adult health outcomes (Johnson, Riley, Granger, & Riis, 2013). Grasso and colleagues (2016) found that children exposed to trauma early in childhood are at higher risk to be exposed again later in childhood. They point to childhood sexual trauma and then the experience of trauma in adolescents as being particularly detrimental to adolescent outcomes. If adversity occurs during sensitive periods, it may alter biological systems (e.g. gene expression) which would explain poor adult health outcomes. Furthermore, the notion that the social environment becomes embodied via physiological pathways further illustrates the interaction between the multiple domains we inhabit (Shonkoff & Garner, 2012). Groups, such as Consistently High and Substance Abuse and Incarceration, may have experienced ACE during sensitive periods thus explaining the observed impact on adult health.

Putting Results in the Context of Existing Research

Several studies have used LCA to gain a better understanding of the health impacts of stress and adversity. Many studies have focused on adversity in childhood and its impact on adolescent emotional, behavioral and cognitive outcomes (Charak, Ford, Modrowski, & Kerig, 2019; Grasso, Dierkhising, Branson, Ford, & Lee, 2016; Karsberg, Armour, & Elklit, 2014; Oliver et al., 2014), while others focus solely on adult adversity and its subsequent health impact (Deleuze et al., 2015; Gilman et al., 2013). A few studies have evaluated the impacts of ACE on adulthood health and well-being outcomes without taking into account adulthood adversity (Keane, Magee, & Kelly, 2016; Roos et al., 2016). Although similar to a life course approach, the omission of adulthood adversity may hamper their ability to identify later life risks and resiliencies as well as opportunities for intervention that can impact adult health and well-being. It is important to note that the studies cited above have been conducted in populations throughout the globe, indicating the consistent effects of ACE on physical and mental health.

Research conducted in a Swedish birth cohort, used a similar approach to ours in the selection of childhood and adulthood adversity (Almquist and Brännström 2018). The authors evaluate receipt of social assistance unemployment, and mental health problems in adulthood and match them to the same adversity in the participant’s family during childhood. They go on to create profiles (using sequence analysis) of adulthood adversity and examine the association with childhood adversity, finding that participants exposed to one or more of these adversities during childhood had higher odds of experiencing them as adults. The deleterious effects of cumulative disadvantage are well highlighted in this study. Previous work in this same cohort used LCA to create classes based on adulthood adversity and evaluated these classes against childhood adversities to find that adversity in childhood was associated with higher risk of being in a more disadvantaged adulthood cluster (Almquist 2016). Given the differences in the variables used it is difficult to make direct comparisons with our study, but these studies exemplify the recurrence of adversity over the life course as well as the rich life course perspective gained from examining both ACE and AAE.

Strengths & Limitations

Our study has several strengths. First this is a creative use of surveillance data to assess life course adversity. This kind of surveillance data is readily available and contains rich information about both child and adulthood adversity that can be used by researchers interested in examining related questions (e.g., see (Putnam-Hornstein, Needell, & Rhodes, 2013) regarding the value of population-based data for risk and protection assessments. It should be noted that the Almquist’s (2016, 2018) studies that examine both ACE and AAE use Swedish data where linkages to a large number of national registries is possible. Although this is not possible in the U.S. context, the BRFSS, limitations withstanding, allows us to capture life course adversity in the absence of robust life course cohorts. In addition, although respondents to the BRFSS are a representative population we were still able to identify marginalized subgroups in the data. Furthermore, our large sample size allowed us to identify several distinct classes. Several earlier studies were able to identify two or three class solutions, usually corresponding to high, medium and low adversity (Karsberg et al., 2014; Young-Wolff et al., 2013), missing some of the nuance and richness seen in the classes we identified.

In terms of limitations ours is a descriptive, cross-sectional study. Future work using longitudinal data will help better understand causal relationships. In addition, the retrospective collection of ACE does not allow for the assessment of timing of childhood adversity. A more robust examination of critical and sensitive periods would require more detail on when in childhood these adversities occurred and how long they lasted. This type of information is critical to predicting future health outcomes. We should also note that the Substance Abuse and Incarceration group was comparatively small. Data for this group is important given the current context and growing trends of incarceration, but should be interpreted with caution until a more in depth examination of this group is available. Lastly the health measures used here were self-reported and some were captured with a single item. Although the corpus of findings reinforces interpretation, caution is merited as to measurement sufficiency in clinical domains.

Conclusion

This study used person-centered analysis to begin to address important knowledge gaps regarding life course adversity. Findings suggest six distinct, substantively meaningful subgroups based on adversity in both childhood and adulthood. The classes we identified can help inform the work of service providers. Beyond the traditional primary care and mental health providers, other service providers such as disability services, juvenile and criminal justice settings, and family serving services as well as support systems including shelters, food banks and welfare offices can also be engaged. Our findings further suggest that early life adversity can be targeted through schools, parenting supports, transitional supports into early adulthood and through the engagement of work places where parents are employed. The often specialized nature of services provided in many settings today may benefit from a more holistic view, thus providing clients with services to address many of their needs at once. By infusing awareness of life course adversity across the many health and safety net services we can help identify adversity as early as possible and may help actively foster resilience.

Figure 2.

Response Probabilities of Latent Classes with High AAE

Note: ACE Dep=Depression, ACE Subst=Substance Abuse, ACE Incar=Incarceration, ACE Div=Divorce/Separation, ACE PhyAb=Physical Abuse, ACE SexAb=Sexual Abuse. AAE Dep=Adult Depression, AAE Subst=Adult Substance Abuse, AAE Incar=Adult Incarceration, AAE Div=Adult Divorce/Separation, AAE DomVio=Adult Domestic Violence, AAE SexVio=Adult Sexual Violence.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, P2C HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology at the University of Washington and a grant via the Foundation for Healthy Generations.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Almquist YB (2016). Childhood origins and adult destinations: The impact of childhood living conditions on coexisting disadvantages in adulthood. International Journal of Social Welfare, 25(2), 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Almquist YB, & Brannstrom L. (2018). Childhood adversity and trajectories of disadvantage through adulthood: Findings from the Stockholm birth cohort study. Social Indicators Research, 136(1), 225–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, & Muthén B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Using the bch method in mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary model. Mplus Web Notes, 21(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, Herrick H, & Proescholdbell S. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences related to poor adult health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 106(2), 314–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JE, Noll JG, Putnam FW, & Trickett PK (2009). Sexual and physical revictimization among victims of severe childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33(7), 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell C, Jones J, Gombojav N, Linkenbach J, & Sege R. (2019). Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample: Associations Across Adverse Childhood Experiences Levels. JAMA Pediatrics, e193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttorff C, Ruder T, & Bauman M. (2017). Multiple chronic conditions in the United States: RAND Santa Monica, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum L, Griffin T, Riding D, Wynkoop K, Anda R, Edwards V, et al. (2010). Adverse childhood experiences reported by adults-five states, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59(49), 1609–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Knoble NB, Shortt JW, & Kim HK (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 231–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau. (2018, March 8). Veterans statistics. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2015/comm/veterans-statistics.html

- Charak R, Ford JD, Modrowski CA, & Kerig PK (2019). Polyvictimization, emotion dysregulation, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, and behavioral health problems among justice-involved youth: A latent class analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(2), 287–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronholm PF, Forke CM, Wade R, Bair-Merritt MH, Davis M, Harkins-Schwarz M, et al. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences: Expanding the concept of adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(3), 354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutuli J, & Herbers JE (2014). Promoting resilience for children who experience family homelessness: Opportunities to encourage developmental competence. Cityscape, 16(1), 113–140. [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, & McEwen BS (2012). Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiology and Behavior, 106(1), 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice M, Ellis BJ, & Shirtcliff EA (2011). The adaptive calibration model of stress responsivity. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(7), 1562–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze J, Rochat L, Romo L, Van der Linden M, Achab S, Thorens G, et al. (2015). Prevalence and characteristics of addictive behaviors in a community sample: A latent class analysis. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 1, 49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Anda RF, Dube SR, Dong M, Chapman DF, Felitti VJ (2005). The wide-ranging health consequences of adverse childhood experiences In Kendall-Tackett KA, & Giacomoni SM (Eds.). Child victimization: Maltreatment, bullying and dating violence, prevention and intervention. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute, Inc.. [Google Scholar]

- Exley D, Norman A, & Hyland M. (2015). Adverse childhood experience and asthma onset: A systematic review. European Respiratory Review, 24(136), 299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Academic Pediatrics, 9(3), 131–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz J, de Graaff AM, Caisley H, van Harmelen AL, & Wilkinson PO (2018). A systematic review of amenable resilience factors that moderate and/or mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and mental health in young people. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Grasso DJ, Hawke J, & Chapman JF (2013). Poly-victimization among juvenile justice-involved youths. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(10), 788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Trinh NH, Smoller JW, Fava M, Murphy JM, & Breslau J. (2013). Psychosocial stressors and the prognosis of major depression: A test of axis iv. Psychological Medicine, 43(2), 303–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli A, Reynolds AJ, Mondi CF, & Ou SR (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and adult well-being in a low-income, urban cohort. Pediatrics, 137(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso DJ, Dierkhising CB, Branson CE, Ford JD, & Lee R. (2016). Developmental patterns of adverse childhood experiences and current symptoms and impairment in youth referred for trauma-specific services. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(5), 871–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication II: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(2), 113–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfon N, Larson K, Lu M, Tullis E, & Russ S. (2014). Lifecourse health development: Past, present and future. Maternal Child Health Journal, 18(2), 344–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SB, Riley AW, Granger DA, & Riis J. (2013). The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics, 131(2), 319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsberg S, Armour C, & Elklit A. (2014). Patterns of victimization, suicide attempt, and posttraumatic stress disorder in greenlandic adolescents: A latent class analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(9), 1389–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane CA, Magee CA, & Kelly PJ (2016). Is there complex trauma experience typology for Australian’s experiencing extreme social disadvantage and low housing stability? Child Abuse and Neglect, 61, 43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Irving M, Lepage B, Dedieu D, Bartley M, Blane D, Grosclaude P, et al. (2013). Adverse childhood experiences and premature all-cause mortality. European Journal of Epidemiology, 28(9), 721–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch L. (2017). Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model. Health & justice, 5(1), 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindert J, von Ehrenstein OS, Grashow R, Gal G, Braehler E, & Weisskopf MG (2014). Sexual and physical abuse in childhood is associated with depression and anxiety over the life course: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Public Health, 59(2), 359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan-Greene P, Kim BE, & Nurius PS (2016). Childhood adversity among courtinvolved youth: Heterogeneous needs for prevention and treatment. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 5(2), 68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald G, Livingstone N, Hanratty J, McCartan C, Cotmore R, Cary M, Glaser D, et al. (2016). The effectiveness, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for maltreated children and adolescents: an evidence synthesis. Health Technology Assessment, 20(1), 508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie-Mitchell A, & Kostolansky R. (2019). A Systematic Review of Trials to Improve Child Outcomes Associated With Adverse Childhood Experiences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(5), 756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, & Seeman T. (1999). Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress. Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 30–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta D, Klengel T, Conneely KN, Smith AK, Altmann A, Pace TW, et al. (2013). Childhood maltreatment is associated with distinct genomic and epigenetic profiles in posttraumatic stress disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(20), 8302–8307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, Guinn AS (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 states. Journal of American Medical Association Pediatrics, 172(11), 1038–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, Guinn AS, Chen J, Klevens J, et al. (2019). Vital Signs: Estimated Proportion of Adult Health Problems Attributable to Adverse Childhood Experiences and Implications for Prevention - 25 States, 2015–2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(44), 999–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Topitzes J, & Reynolds AJ (2013). Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: A cohort study of an urban, minority sample in the U.S. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(11), 917–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh A, Matheson FI, Daoud N, Hamilton-Wright S, Pedersen C, Borenstein H, et al. (2013). Linking childhood and adult criminality: Using a life course framework to examine childhood abuse and neglect, substance use and adult partner violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(11), 5470–5489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalvo-Liendo N, Fredland N, McFarlane J, Lui F, Koci AF, & Nava A. (2015). The intersection of partner violence and adverse childhood experiences: Implications for research and clinical practice. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(12), 989–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B. (2007). Statistical analysis with latent variables using mplus. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nurius PS, Green S, Logan-Greene P, & Borja S. (2015). Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: A stress process analysis. Child Abuse and Neglect, 45, 143–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan A, Epel E, Lin J, Wolkowitz O, Cohen B, Maguen S, et al. (2011). Childhood trauma associated with short leukocyte telomere length in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 70(5), 465–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver BR, Kretschmer T, & Maughan B. (2014). Configurations of early risk and their association with academic, cognitive, emotional and behavioural outcomes in middle childhood. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(5), 723–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer SC, Nurius PS, & Green S. (2016). Homelessness history impacts on health outcomes and economic and risk behavior intermediaries: New insights from population data. Families in Society, 97(3), 230–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI (2010). The life course and the stress process: Some conceptual comparisons. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B(2), 207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, & Meersman SC (2005). Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(2), 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam-Hornstein E, Needell B, & Rhodes AE (2013). Understanding risk and protective factors for child maltreatment: The value of integrated, population-based data. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(2–3), 116–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray EC, Arpan L, Oehme K, Perko A, & Clark J. (2019). Helping students cope with adversity: the influence of a web-based intervention on students’ self-efficacy and intentions to use wellness-related resources. Journal of American College Health, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebbe R, Nurius PS, Courtney ME, & Ahrens KR (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and young adult health outcomes among youth aging out of foster care. Academic Pediatrics, 18(5), 502–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos LE, Afifi TO, Martin CG, Pietrzak RH, Tsai J, & Sareen J. (2016). Linking typologies of childhood adversity to adult incarceration: Findings from a nationally representative sample. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(5), 584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, & Garner AS (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Kubzansky LD, McLaughlin KA, & Koenen KC (2013). Childhood adversity and inflammatory processes in youth: A prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(2), 188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Jimenez MP, Roberts CT, & Loucks EB (2015). The role of adverse childhood experiences in cardiovascular disease risk: A review with emphasis on plausible mechanisms. Current Cardiology Reports, 17(10), 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub F, & Boynton-Jarrett R. (2017). Modifiable resilience factors to childhood adversity for clinical pediatric practice. Pediatrics, 139(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young-Wolff KC, Hellmuth J, Jaquier V, Swan SC, Connell C, & Sullivan TP (2013). Patterns of resource utilization and mental health symptoms among women exposed to multiple types of victimization: A latent class analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(15), 3059–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski DS (2009). Child maltreatment and adult socioeconomic well-being. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33(10), 666–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]