Abstract

Objectives

To explore women’s experiences of breastfeeding beyond infancy (>1 year). Understanding these experiences, including the motivators, enablers and barriers faced, may help inform future strategies to support and facilitate mothers to breastfeed for an optimal duration.

Design

An exploratory qualitative study using an interpretive approach. Nineteen semistructured interviews were conducted (in person, via phone or Skype), transcribed and thematically analysed using the framework method.

Setting

Participants drawn from across the UK through online breastfeeding support groups.

Participants

Maximum variation sample of women currently breastfeeding a child older than 1 year, or who had done so in the previous 5 years. Participants were included if over 18, able to speak English at conversational level and resident in the UK.

Results

The findings offer insights into the challenges faced by women breastfeeding older children, including perceived social and cultural barriers. Three core themes were interpreted: (1) parenting philosophy; (2) breastfeeding beliefs; (3) transition from babyhood to toddlerhood. Women had not intended to breastfeed beyond infancy prior to delivery, but developed a ‘child-led’ approach to parenting and internalised strong beliefs that breastfeeding is the biological norm. Women perceived a negative shift in approval for continued breastfeeding as their child transitioned from ‘baby’ to ‘toddler’. This compelled woman to conceal breastfeeding and fostered a reluctance to seek advice from healthcare professionals. Mothers reported feeling pressured to breastfeed when their babies were young, but discouraged as children grew. They identified best with the term ‘natural-term breastfeeding’.

Conclusions

This study suggests that providing antenatal education regarding biological weaning ages and promotion of guidelines for optimum breastfeeding duration may encourage more women to breastfeed for longer. Promoting the concept of natural-term breastfeeding to mothers, and healthcare professionals, employers and the public is necessary to normalise and encourage acceptance of breastfeeding beyond infancy.

Keywords: qualitative research, public health, maternal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This interpretive, exploratory qualitative study contributes to the growing, but limited, literature on longer term breastfeeding and identifies some potential practical solutions which may support women to breastfeed for an optimal duration.

Due to the potentially sensitive nature of the topic, it can be difficult to identify and access breastfeeding women; however, this study used social media as a platform for recruitment, which allowed construction of a maximum variation sample, thereby increasing transferability.

This study has a relatively large sample size with rich data, and analytic data saturation was achieved.

Participants were predominantly white and highly educated, which could limit transferability; however, this may also reflect that this demographic is most likely to breastfeed past infancy.

One of the authors has breastfed an older child, so a reflexive approach was important to mitigate the ways in which this may have inadvertently shaped data collection; a second analyst provided a different stance.

Introduction

The fundamental importance of breastfeeding to the health and development of children is well established.1 The Lancet Breastfeeding Series synthesises comprehensive evidence demonstrating that breastfeeding offers the best nutritional start for infants, conferring short-term benefits such as lower infectious morbidity and mortality, as well as life-long protection against obesity and diabetes mellitus.1 2 Mothers who breastfeed also benefit from reduced risk of breast cancer, and potentially ovarian cancer and diabetes.1

The WHO currently recommends that infants in all settings should be exclusively breastfed until 6 months of age, after which they should receive nutritious complementary foods alongside continued breastfeeding for 2 years or beyond.3 However, it is important to highlight that the WHO recommendation lacks clarity regarding the duration for which the benefits of breastfeeding are sustained beyond 24 months.

Significant efforts have been made to promote breastfeeding, often focused on educating new and expectant mothers regarding benefits of breastfeeding,4 which to some extent have been successful. The last national Infant Feeding Survey (IFS) was conducted in 2010, and the results showed that 81% of babies born in the UK were breastfed at birth.5 However, that proportion fell sharply: at 6 months post partum, the proportion of mothers exclusively breastfeeding was around 1%, and only 25% of infants were still receiving any breast milk.5 Breastfeeding status after 6 months was not recorded and so it is difficult to estimate breastfeeding rates beyond this.6 The IFS has now been discontinued, and data relating to breastfeeding initiation in England is captured and reported by National Health Service Digital via the Maternity Services Data Set, and breastfeeding status at 6–8 weeks through the Children and Young People’s Health Services Data Set.7 As such, more recent data on breastfeeding rates at 6 months are unavailable. However, in 2018, Scotland published the results of its Maternal and Infant Nutrition Survey, in which 43% of respondents reported providing breast milk to their infants at 6 months,8 although no data were provided about exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months. These data suggest that more women are breastfeeding and for longer. It is therefore important to understand the experiences and needs of these mothers who continue breastfeeding beyond 6 months.

A recent large meta-analysis determined that breastfeeding should continue until at least 2 years to achieve its full effect.1 Protection from infectious diseases has been shown to persist into at least the second year of life, and longer breastfeeding durations were associated with a higher IQ, and a lower risk of obesity in the long term.1 2 Additionally, fostering optimal breastfeeding duration has economic advantages, both in terms of reducing healthcare expenditure through decreasing infant morbidity and mortality,9 and increasing children’s educational potential and likely future earnings, while simultaneously promoting social equity.10

Almost all women are biologically able to breastfeed, except for those with a (very) few limiting medical disorders.11 While initiation rates are high,5 most women discontinue much earlier than recommendations advise. It has been suggested that once breastfeeding has been established, one of the main factors influencing breastfeeding duration is the social environment in which breastfeeding occurs,12 with a wide range of social, cultural and market factors shaping decisions to continue, or persist.13 Research has found that worries about breastfeeding in public are prevalent,14 and negative reactions from others, and the feelings invoked by those reactions, contribute to decisions about how long to breastfeed.15 Previous qualitative research with breastfeeding mothers has found that many receive persistent, unsolicited advice about the need to wean and are encouraged to discontinue from nursing ‘too long’.4 Breastfeeding behaviours are, it seems, open to public evaluation, commented on and criticised by family, friends and strangers,16 resulting in stigma and social sanctioning.4 17 While a substantial body of qualitative research exists examining women’s breastfeeding experiences, there are relatively fewer studies that have explored experiences of breastfeeding beyond 6 months.18 The small number of more recent studies has found that women nursing older children feel highly scrutinised,19 frequently face negative attitudes and criticism from others,18–21 and experience marginalisation.19

Building on this limited literature, this interpretive qualitative study aims to focus explicitly on women’s experiences of breastfeeding beyond infancy (>1 year of age). Understanding women’s experiences, including the motivators, enablers and barriers faced, may help inform future strategies to support and facilitate mothers to breastfeed for an optimal or ‘natural-term’ duration. Throughout the paper, the term ‘weaning’ is used to describe the process of stopping breastfeeding and is distinct from the process of introducing supplementary foods.

Methods

Aim

To explore women’s experiences of breastfeeding beyond 1 year of age including: beliefs and motivations regarding breastfeeding beyond infancy, perceptions of support, perceptions of enablers, facilitators and barriers to continued breastfeeding and the influence of these factors on feeding decisions.

Design and setting

This exploratory, interpretive qualitative study was deemed the most appropriate design to explore decision-making processes, beliefs and experiences,22 and particularly well suited to researching breastfeeding experiences.23 The study is reported using Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research guidelines24 (see online supplementary additional file 1). Semistructured interviews were chosen to better elicit accounts that provided a deep understanding of women’s perceptions and their impact on their behaviour.25 They were favoured over a group data collection approach in order to allow individual narratives to be explored. Interviews were conducted face to face, or via phone or Skype, depending on participant preference and location so as not to limit participation due to geographical location or cost.

bmjopen-2019-035199supp001.pdf (43.5KB, pdf)

Participants

Participants were women aged at least 18 years currently breastfeeding a child older than 1 year, or who had done so in the previous 5 years. Participants were included if able to speak English at conversational level and willing and able to provide informed consent. Given that the social and cultural climate in which breastfeeding occurs has been shown to influence women’s experiences,12 only women resident in the UK who had breastfed for an extended period were eligible to participate.

Sampling and recruitment

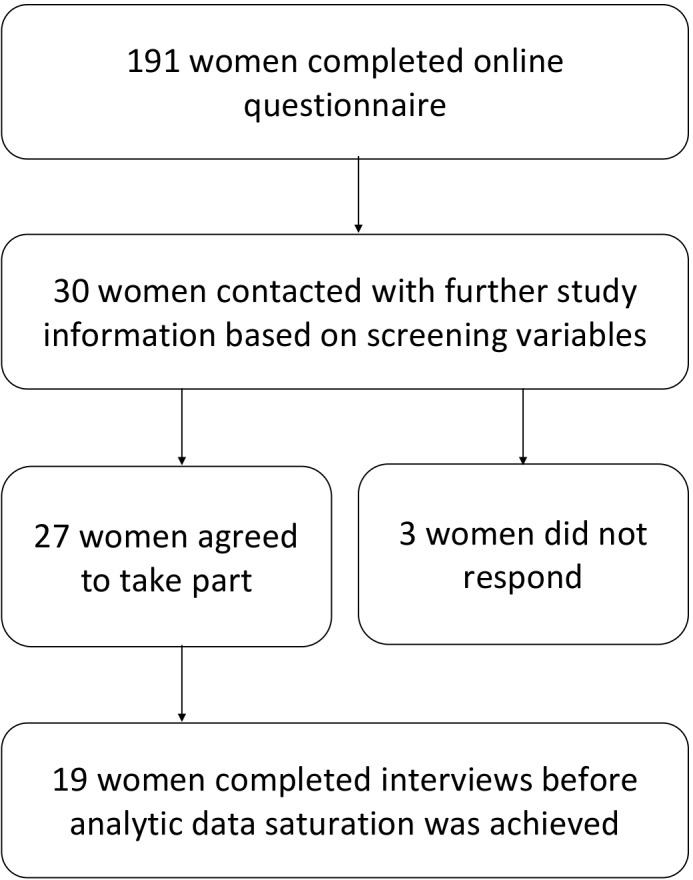

A purposive sample using a maximum variation sampling frame26 including age, number of children and longest duration breastfeeding one child was employed. Recruitment adverts were posted through online Facebook breastfeeding support groups. Potential participants were invited to complete an online screening survey, which assessed eligibility and collected data on selected sampling variables to facilitate sample construction. One hundred ninety-one women completed the survey, all of which were eligible. Based on sampling frame variables highlighted above, 30 women were contacted via email with further detailed study information: 27 were willing to take part; 3 did not respond. Data collection continued to be scheduled until analytic saturation was achieved, defined as the point when no further themes or concepts were surfaced from further interviews.27 Nineteen interviews contributed to the final dataset from across the UK. Women who were not interviewed were politely informed by email that data were no longer being actively collected. A flow chart of this process is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart summary of recruitment and sampling process.

Data collection

Prior to interview, all participants provided informed consent. In the case of telephone or Skype interviews, this was competed electronically. Participants were requested to complete a short demographic questionnaire to facilitate description of the sample (see the Results section). Interviews were conducted by AJT (female, two children). A topic guide was developed, informed by the existing literature on breastfeeding determinants (see box 1), and used flexibly as a framework for the semistructured interviews. Analysis occurred concurrently with data collection, allowing iterative updating of the topic guide and coding frame. Open questions were used to facilitate extended answers, and probes to extract further detail. Interviews were conducted either face to face (n=6), via telephone (n=8), or via Skype (n=5), and lasted an average of 45 min (range: 28–77 min). Face to face interviews were conducted in the participants’ own homes at mutually agreed times. Participants’ children or other family members could be present, at participants’ discretion. Interviews were digitally audio recorded with consent, and brief field notes made to aid reflection. All participants were offered a £10 shopping voucher on interview completion.

Box 1. Sample of discussion guide prompts.

Sample prompts for discussion

When you were pregnant with your first baby, what were your thoughts on breastfeeding?

Can you tell me your thoughts on weaning? How did you/do you plan to manage the process?

Why have you chosen/did you choose to continue breastfeeding your child?

How do you feel about nursing in public? Has this changed over time and how?

Can you tell me about support you have had for continuing to breastfeed?

Are you part of any breastfeeding support groups? Why did you join, and what do you get from these groups?

Has anything ever made you consider stopping breastfeeding?

Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and anonymised, removing any personal identifying information. Transcripts were read repeatedly to enable familiarisation and immersion. Interview transcripts were coded inductively by one of the authors (AJT), facilitated by NVivo V.11 software, and analysed thematically, guided by the framework method (see table 1).28 Initial codes and themes were discussed and agreed by two authors (AJT and LLJ), before developing an analytical framework into which subsequent transcripts were charted. Charting produced a highly organised matrix of summarised data, which allowed data to be compared and contrasted while retaining the wider context of each case, thereby encouraging thick description. The analytical framework was finalised after extensive discussion between authors.

Table 1.

Analysis process

| Summary of framework approach analysis procedure | |

| Stage 1: transcription | Audio recordings are used to produce a verbatim transcription of the interview. Since the content is what is of primary interest, clean verbatim transcriptions are sufficient. The transcription process is a good opportunity to begin immersion in the data. |

| Stage 2: familiarisation | Familiarisation with whole interviews using audio recordings and/or transcripts and any field notes is a vital stage in interpretation. Any initial analytical notes, thoughts or impressions are recorded. |

| Stage 3: coding |

Transcripts are read line by line, and a label (‘code’) is applied to each passage which summarises the important messages from that section. Because this study was inductive in nature, an open coding framework was applied, that is, coding anything potentially relevant rather than applying predefined codes. |

| Stage 4: development of analytical framework | When some initial transcripts have been coded, the researcher decides on a set of codes which will then be applied to all subsequent transcripts. Codes can be grouped together into categories or themes. |

| Stage 5: application of analytical framework |

The working analytical framework is applied to all subsequent transcripts, and is iteratively updated as new codes emerge. In this study, NVivo software was used to facilitate this stage. |

| Stage 6: charting data into framework matrix |

A matrix is generated using a spreadsheet, and the data from each transcript are ‘charted’ into the matrix. Data are summarised by category from each transcript, in a way which reduces the volume of data while still retaining the original meanings and sentiments of the participant. Interesting or illustrative quotations are also included in the matrix. |

| Step 7: interpretation | Gradually, characteristics of the data are identified, and theories or models explaining the narrative can be developed. |

Patient and public involvement

There were no funds or time allocated for patient and public involvement so we were unable to involve patients. We have invited patients to help us develop our dissemination strategy.

Results

Nineteen interviews contributed to the final dataset. Table 2 contains a summary of participants’ demographic characteristics.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics table

| Participant Identifier | Age (years) | Number of children | Duration breast feeding (years) | Currently breast feeding? | Marital status | Employment status | Highest level of education | Ethnicity |

| P1 | 40–49 | 1 | 3–4 | Yes | Married | Employed—part time | Postgraduate | White British |

| P2 | 30–39 | 1 | 1–2 | Yes | Married | Employed—part time | Postgraduate | White British |

| P3 | 30–39 | 2 | 2–3 | No | Married | Employed—full time | Postgraduate | White British |

| P4 | 30–39 | 2 | 3–4 | Yes | Married | Student | Postgraduate | White British |

| P5 | 30–39 | 2 | 2–3 | No | Married | Self-employed | Postgraduate | White British |

| P6 | 40–49 | 2 | 5–6 | Yes | Married | Employed—full time | Postgraduate | White British |

| P7 | 40–49 | 4 | 5–6 | Yes | Married | Homemaker | Bachelor’s degree | White Other |

| P8 | 30–39 | 1 | 1–2 | Yes | Married | Employed—full time | Postgraduate | White Other |

| P9 | 40–49 | 1 | 7–8 | Yes | Single | Self-employed | Bachelor’s degree | White British |

| P10 | 20–29 | 2 | 3–4 | Yes | Married | Employed—full time | Bachelor’s degree | White British |

| P11 | 30–39 | 1 | 3–4 | Yes | Cohabiting | Employed—full time | Bachelor’s degree | White British |

| P12 | 20–29 | 1 | 1–2 | Yes | Cohabiting | Employed—full time | Bachelor’s degree | White British |

| P13 | 30–39 | 3 | 3–4 | Yes | Married | Homemaker | Bachelor’s degree | White British |

| P14 | 30–39 | 1 | 3–4 | Yes | Cohabiting | Employed—part time | A level | White British |

| P15 | 30–39 | 4 | 4–5 | Yes | Married | Self-employed | Postgraduate | White British |

| P16 | 30–39 | 2 | 3–4 | Yes | Married | Homemaker | Postgraduate | White British |

| P17 | 20–29 | 2 | 5–6 | Yes | Single | Homemaker | GCSE | White British |

| P18 | 30–39 | 1 | 2–3 | Yes | Married | Employed—full time | Postgraduate | Asian British |

| P19 | 30–39 | 1 | 1–2 | Yes | Married | Employed—part time | Bachelor’s degree | White British |

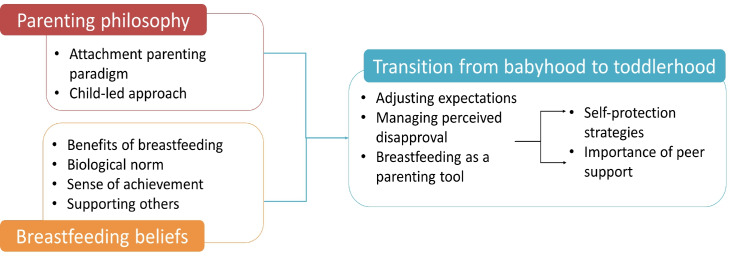

Three core themes were interpreted within the dataset: (1) parenting philosophy; (2) breastfeeding beliefs; (3) transition from babyhood to toddlerhood (figure 2). Exemplar quotations are embedded in the text, and further quotes are available in online supplementary additional file 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of themes.

bmjopen-2019-035199supp002.pdf (50.5KB, pdf)

Parenting philosophy

Attachment parenting paradigm

Women’s parenting styles and choices fell under the theme labelled attachment parenting paradigm (see the Discussion section for more explanation of this term), and women described their approach as ‘gentle parenting’ (P14) which they felt contributed to their successful breastfeeding relationships. Some women identified themselves as ‘attachment parents’ (P16), while others were unfamiliar with the term but described parenting practices consistent with the philosophy. All women breastfed their children on demand during infancy, all but two regularly coslept with their children, and all felt it was important to rapidly respond to infant crying: ‘I’ve not been one to leave my child crying on their own. Children cry, that’s fine, if they’re with somebody.’ (P11). Most women had not intended to be ‘attachment parents’ prior to delivery, but instead adopted the approach after the child was born through an instinctive desire to respond to their child’s cues and subsequently learnt more about the philosophy. Forming a secure attachment with children was identified as being important. Continuing to breastfeed, they felt promoted child security and confidence:

…because they [child] have that closeness with you, security of breastfeeding, they’re generally much more comfortable and settled when they’re away from you. And we’ve never had an issue with him going to someone else, he’ll quite happily go and play or go and be in a classroom. (P1)

Women felt their chosen parenting style was different but gave their child the self-assurance to be more independent. Participants felt there was a culture of forcing babies to be overly independent at a young age, ‘the majority of people still cry it out’ (P14). They described parents were under social pressure to conform to certain behaviours, such as sleep training. As this mother describes:

There were so many things that I felt I had to stop, like I had to stop sleeping with the baby, they have to go to their cot, you have to sleep train them. (P14)

Women felt that societal attitudes surrounding infant sleep were particularly unhelpful for breastfeeding mothers, and could damage nursing relationships:

Health visitors telling you to sleep train your baby that’s breastfed because they wake up to feed at night time. It’s quite normal for a breastfed child to wake to feed at night. (P10)

That’s also something that you see in the press and the national health recommendations ‘don’t co-sleep, don’t bedshare’. I think they put the wrong slant on it, because it’s such an important part of a successful breastfeeding relationship. (P2)

The women were aware of the link between cosleeping and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS; see the Discussion section), but most felt that the perceived benefits of cosleeping outweighed the risk narrative from other sources.

Child-led approach

In all aspects of parenting, women emphasised the importance of following the child’s cues and allowing the child to do things at their own pace: ‘I’m very much about letting him do things when he’s ready’ (P9). For most participants, this philosophy also extended to weaning. Women explained that they continued to breastfeed because their child was not yet ready to stop: ‘I would have quite happily have stopped two years ago but he’s kind of led it, and I’ve just let him really’ (P6). Women generally felt that allowing their child to self-wean was more important than continuing to breastfeed for a specified length of time:

No one gives you a medal for breastfeeding, but I feel like I’ll get one if I can complete his breastfeeding journey on his terms…I feel like I’ll give myself one for it. (P10)

Breastfeeding beliefs

Benefits of breastfeeding

All the women strongly believed that breastfeeding had been, and continued to be, beneficial for their children in terms of nutrition and bonding. Health benefits were cited as the most important, including improved long-term health outcomes, and avoidance of short-term illnesses: ‘Although he got ill when he was a toddler, I do believe his illnesses were shorter and probably less frequent.’ (P6). Participants also explained that when their children were ill they would often continue nursing even if they refused other foods and liquids, and were reassured that this would provide hydration and antibodies:

When he is sick he can have my milk and I don’t have to worry quite so much about whether he’s hydrated and I know that he’ll probably get better faster. (P7)

Biological norm

A narrative repeatedly expressed was the strong belief that continued breastfeeding is the biological norm: ‘For me the biggest thing is that it’s biologically normal. And it’s a normal thing to do. Other cultures see it as normal.’ (P5). Women believed that adhering to the practices to which our ancestors were adapted would allow children to achieve their biological potential. Most participants discussed human biological weaning ages as a justification: ‘It’s the biological norm for us as organisms…they naturally wean when they lose their milk teeth and their jaw shape changes so they can’t latch.’ (P11). Participants also cited traditional societies who continue to breastfeed their child beyond infancy:

I’ve read about other societies that children will feed until they get their back molars when they’re about 6 or 7. (P4)

Women identified best with the term ‘natural-term breastfeeding’, explaining that breastfeeding beyond infancy is an aspect of biological heritage. All participants expressed dislike of the term ‘extended breastfeeding’ because ‘it makes it sound not-normal’ (P18), and believed that the practice was perceived as ‘extended’ due to culturally imposed expectations:

I believe in natural-term breastfeeding. It’s important that people know it’s not extended, it’s normal! (P13)

Sense of achievement

All participants expressed pride in their breastfeeding and believed it was an important achievement. Paradoxically, successful breastfeeding engendered pride for participants while they simultaneously expressed the belief that breastfeeding was normal and natural. The women rationalised this inconsistency by describing breastfeeding as challenging and therefore that success demonstrated commitment. Some women expressed feelings of failure and guilt due to difficulties conceiving or traumatic births, but felt a sense of redemption having successfully breastfed:

For me breastfeeding has been healing. I didn’t give birth in the way that I wanted to so being able to breastfeed has been a gift. It will be one of my greatest achievements (P9)

I think that because I couldn’t conceive them [naturally], I couldn’t give birth to him naturally…I think it made me more determined to [breast]feed. It was the one thing I could do. (P6)

Supporting others

All the women expressed a desire to support other breastfeeding mothers. Many acknowledged having experienced challenges in their own breastfeeding journeys, and felt they would not have succeeded without support. Most participants reported that ‘there’s a real lack of quality support’ (P1), and worried that women are sometimes encouraged to give up breastfeeding rather than supported to continue. Support was considered particularly important given that many people have mothers and grandmothers who did not breastfeed so: ‘There’s not the natural support that we would traditionally have had in the family’ (P11).

Additionally, participants found that conversations around breastfeeding were often a ‘very difficult discussion’ (P1) with new or expectant mothers because their desire to support women could be perceived as pressure or criticism: ‘It’s hard to say without sounding like I’m attacking people who do things differently.’ (P13). Although the women felt proud of their own breastfeeding achievements and wanted to share their experiences, they described concern that expressing this could be perceived by others as conceited.

Transition from babyhood to toddlerhood

Adjusting expectations

All of the women had planned to initiate breastfeeding, but had not intended to breastfeed beyond 1 year at the time of their first pregnancy. Instead, participants readjusted their breastfeeding intentions as children grew. Many of the women reported that they had not been aware of the recommendations regarding breastfeeding duration antenatally, and had been unaware it was possible to continue to feed an older child:

I think it’s very ingrained in our society that kids don’t breastfeed: Babies wean onto solids and that’s the end of it. That’s what I thought happened. I didn’t realise it [lactation] carried on. (P12)

Moreover, prior to having children, many women felt that breastfeeding an older child was ‘weird’ (P1) or ‘crazy’ (P13), and as such had to overcome their own prejudices as their children grew and continued to breastfeed.

All women had breastfed on demand when their infants were very young, but began to introduce boundaries as their babies became toddlers. The reasons for introducing boundaries varied, but were commonly cited as practical reasons such as encouraging children to sleep for longer stretches, and to avoid the need for nursing outside the home. The women felt it was important that the child could understand these boundaries and therefore rationalise and negotiate to agree mutually acceptable restrictions. Some women night weaned their children, while others would limit the number or length of feeds. This negotiation process was important in allowing mothers to continue nursing, because continued breastfeeding without restrictions became tiring and impractical:

He has that little bit more understanding… We now have a limit that there’s a time in the evening by which he needs to have milk because I find the later it gets the more uncomfortable. I’m tired, I get fed up, so he’s respecting that. (P9)

Managing perceived disapproval

Women described how perceived approval for breastfeeding changed as their child transitioned from ‘baby’ to ‘toddler’. Participants felt pressured to breastfeed when their babies were young, but discouraged as their child grew. Women were criticised for continuing to nurse and were openly questioned by family and coworkers about weaning intentions. The age at which they became aware of this sea change in attitudes varied, but was typically between 1 and 2 years. The child’s chronological age was a factor in this attitudinal shift; the child’s physical size and developmental abilities were also influential. Milestones perceived as significant in transitioning to toddler were walking and the child being ‘able to ask for it [breast milk]’ (P11). Participants described being made to feel like an ‘outcast’ (P14) or ‘outsider’ (P17). Although the women felt judged, perceived disapproval was not sufficient to motivate weaning for most women. When asked whether anything had ever made them consider stopping breastfeeding, one participant explained she had struggled to cope with persistent criticism from coworkers:

I feel very under the microscope since I’ve come back to work. I’ve had comments like ‘well you’re still feeding her, what do you expect? She’s still using you as a dummy. (P19)

The women perceived that their decision to breastfeed was not considered private by family members or coworkers, and found their choices being discussed publicly:

They all think I’m mad, the whole family! They’re quite nice to my face… It’s more that I know when I’m not in the room that comments are made about it, and I know she [my mother] has said things to my husband. (P6)

Self-protection strategies

In response to expressions of disapproval, women developed various self-protection strategies. Some women were open about their ongoing nursing but felt the need to have ‘scientific research to back it up’ (P11) so they could ‘leap up and defend’ (P5) their decisions. Several women felt protected by the WHO recommendation of breastfeeding for 2 years. However, most women concealed the fact they were breastfeeding an older child. Participants who had previously felt confident to breastfeed in public began to avoid feeding outside of the home:

I would never feed him in public. I probably didn’t feed him in public much after he was two. (P6)

When I picked her up from nursery she would always want a feed and I didn’t just feed her there, I would go and hide somewhere…I didn’t even tell the nursery staff I was still breastfeeding. (P16)

Women avoided conversations about nursing and would ‘keep it quiet’ (P12) or lead others to believe their children were weaned:

You reach a point where other people assume that the child has weaned and there is no reason to correct that assumption…it’s just easier for both parties. (P7)

Accessing support

Peer support groups were important for participants to feel ‘accepted’ (P2) and women were comforted ‘knowing that other people are doing it’ (P10). Many women attended in-person support groups, but online groups became increasingly important as children aged. Peer advice was often sought as many women felt unable to seek professional support for fear of disapproval. Participants reported that healthcare professionals (HCPs) advised weaning as a solution to problems: ‘They’re like 'can’t they just stop?'’ (P10), and several participants reported being offended by comments made by doctors. One participant was asked: ‘Surely you’re not still breastfeeding? Are you going to do that until she goes to university?’ (P16), and another told that continuing to breastfeed would be detrimental to her child:

The consultant made some comments about how I should be considering weaning and not feeding my baby anymore because of her age… he told me there were no benefits to breastfeeding beyond two, and he told me that breastfeeding hinders children’s development. (P5)

Women perceived that many HCPs were not aware of the benefits of breastfeeding and often anticipated negative responses; they therefore did not trust advice if the provider was perceived as unsupportive.

Participants reported that they developed personal concerns during subsequent pregnancies, including uncertainty about whether nursing during pregnancy is safe, and questions regarding the possibility or practicalities of tandem nursing more than one child. Women sought advice on these topics from peer groups, as there was concern that professionals may have insufficient knowledge to provide support, or offer advice coloured by ‘opinion rather than evidence’ (P5).

Breastfeeding as a parenting tool

When children became toddlers, women described using breastfeeding as a practical ‘parenting tool’ (P2). Participants explained that breastfeeding was an effective way to calm and ‘reset’ (P1) toddlers, and was useful to ‘control their behaviour’ (P6). Women would offer breast milk as a ‘modified cuddle’ (P4) if children hurt themselves or became frightened:

If he does get really upset about something and he can’t calm down usually he can settle with having a little bit of milk. So for me it’s like this cure all—it’s so wonderful; I rely on it quite a lot. (P7)

One participant explained that breastfeeding had helped her child cope with a hospital admission:

…they had to put a cannula in. I had him facing me while his arm was out, and I nursed him through that because it was so very distressing. (P9)

Many participants also found breastfeeding a useful tool to manage night-waking, and was described as an ‘easy way to get them back to sleep’ (P12).

Discussion

This study explored the experiences of 19 women who breastfed their child beyond 1 year of age and contributes to the limited, but growing, literature exploring experiences of longer term breastfeeding. Women in this study actively expressed dislike for the term 'extended breastfeeding', which is the label often used to describe the practice of breastfeeding beyond infancy in the academic literature29 and by HCPs; they identified best with the term natural-term breastfeeding. Women reported feeling pressured to breastfeed when their babies were young, but equally felt pressured to discontinue as children grew. Most participants were unaware of WHO guidelines for duration of breastfeeding and thought breastfeeding an older child was ‘weird’ prior to delivery. Women described having to overcome their own prejudices towards breastfeeding older children, and perceived that doing so was considered socially deviant. It was perceived by the women that most HCPs disapprove of breastfeeding beyond infancy, which fostered reluctance to seek advice and support.

Strengths of this study include its relatively large sample size with rich data, and that analytic data saturation was achieved. Due to the potentially sensitive nature of breastfeeding beyond infancy, women are often difficult to identify and access.29 Many previous studies have recruited via advocacy groups6 17 30 31; however, these women may be considerably more open about their breastfeeding status and findings may not be transferable to breastfeeding mothers in general. This study used social media as a platform for recruitment, which allowed construction of a maximum variation sample including women of a range of ages, with different numbers of children, and a wide range of breastfeeding duration, thereby increasing transferability. Employing telephone and Skype interviews as a method of data collection meant participation was not limited by geographical location. Criticisms of these methods suggest that they may impair rapport formation and, in the case of telephone interviews, limit interpretation of non-verbal cues.32 33 However, the interviewer did not feel that rapport was compromised compared with face to face interviews, and research suggests that they are a viable alternative to face-to-face qualitative interviews.32 33 Limitations of the study include that participants were predominantly white and highly educated; however, this may also reflect that this demographic is most likely to breastfeed past infancy.29 These findings may, therefore, not be transferable to women from non-white backgrounds, and exploring the experiences of women from black and minority ethnic communities is an important area for future research to ensure they are supported. It is also notable that only 7 (37%) of the 19 participants were employed full time, and further research exploring the impact of work on breastfeeding continuation may be valuable.

As in all qualitative research, researcher position and reflexivity were important considerations. The interviewer (AJT) is a mother of two who has breastfed an older child herself, and therefore it was important to adopt a reflexive approach34 to mitigate the ways in which this may have inadvertently shaped data collection. The ‘insider’35 position of the interviewer may have been advantageous as participants can be more willing to share their experiences with someone who they perceive to be understanding of their situation.35 In addition, the researcher was equipped with insights to understand implied content, and hence potentially elicit a deeper understanding of the phenomenon.35 An inductive approach to analysis was adopted to ensure that interpreted themes were rooted in the data,36 with a second analyst (LLJ) providing a different stance during interpretation as this researcher had not breastfed beyond infancy.

In line with other studies,19 20 37 38 the decision to continue breastfeeding beyond infancy was shaped by parenting philosophy, and women reported childcare practices consistent with the attachment parenting paradigm. However, this study found that the adoption of this strategy was gradual, and not necessarily held prior to delivery. The adoption of it occurs as the breastfeeding mother learns to parent, and instinctually follows the cues of her infant, ultimately leading to the realignment of parenting beliefs and reinterpretation of health advice. The philosophy holds such importance that the women ultimately adopt subversive and secretive behaviour to continue breastfeeding, which they perceive as necessary to optimally nurture the child. Further, this study found that the philosophy evolved as children grew. Initially, it was entirely ‘child led’, but as children became able to rationalise and negotiate the women introduced boundaries. This negotiation was important for women to continue, as breastfeeding without boundaries became arduous or impractical. Attachment parenting has its roots in Attachment Theory,39 which posits that a strong emotional and physical connection to at least one primary caregiver is critical to development. The term ‘attachment parenting’ describes a style of parenting which is highly responsive to infant cues,40 and typical behaviours include cosleeping, feeding on demand, extensive carrying and holding of infants and rapid response to crying.41 Research suggests that this parenting style is associated with enhanced brain and social development, including peer relationships and schooling, and in the longer term more favourable responses to stress.41

Cosleeping was believed to be important in establishing a successful nursing relationship; however, cosleeping and night feeding are not aligned with contemporary western cultural expectations29 which value prolonged periods of independent sleep.42 For women who wish to cosleep, the provision of safe cosleeping advice may help facilitate establishment and maintenance of successful breastfeeding. It is important to note that there is an association between cosleeping and SIDS.43 44 The National Institute of Clinical Excellence recommends that parents should be informed of this association, but the guidance also states that the causes of SIDS are likely to be multifactorial and a possible causality link with cosleeping is not clearly established.44

One motivator for breastfeeding beyond infancy which was repeatedly discussed was a strong belief in breastfeeding as a biological norm. This echoes prior studies on longer term breastfeeding, in which mothers narrated their decisions to continue breastfeeding as ‘natural’37 and ‘evolutionarily appropriate’.19 From an evolutionary perspective, modern human children are adapted to be breastfed for several years.45 46 Anthropological research estimates that the human biological weaning age falls between two and seven-and-a-half years of age, if based on physiological parameters alone.45 Providing education on biological weaning ages could contribute to normalisation of this behaviour and motivate more women to breastfeed for longer.

Women perceived that breastfeeding an older child was considered socially deviant, and experienced open comments and criticism, mirroring the findings of previous research.6 17–21 37 Women also perceived that most HCPs disapprove of, or are uneducated about, breastfeeding beyond infancy, which fostered reluctance to seek advice and support from professionals. Although UK child health records contain documentation to facilitate conversations regarding infant feeding, the last section which formally documents a discussion about breastfeeding occurs during the 9–12-month developmental review. Given that women were hesitant to actively seek support, inclusion of a discussion around breastfeeding at the 2-year review may promote normalcy and afford women a ‘safe’ opportunity to discuss any issues with an HCP. It may also be prudent for midwives to discuss breastfeeding with multiparous women early during subsequent pregnancies, as women reported that becoming pregnant again prompted breastfeeding concerns. Assessing the views and knowledge of HCPs about this is an important area for future research, to establish whether additional training or guidance is needed.

Conclusion

Enabling optimal breastfeeding duration has potentially enormous health, social and economic advantages.1 2 9 Women experience cultural and social barriers to breastfeeding their children beyond infancy, which may compel women to conceal the behaviour. Moreover, women are reluctant to seek support from HCPs due to fear of judgement or pressure to wean. HCPs should be aware of the benefits of optimal duration breastfeeding, and be mindful of their terminology when consulting with women, for example, using language such as natural-term breastfeeding rather than extended breastfeeding. Inclusion of a breastfeeding section, to facilitate formal documentation, at the 2-year review may promote normalcy and afford women a safe window of opportunity to discuss potential issues. Education regarding biological weaning ages and promotion of WHO guidelines for minimum breastfeeding duration may encourage more women to breastfeed for longer. As well as promoting natural-term breastfeeding to mothers, education targeting the public and HCPs is necessary to encourage normalisation and acceptance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the administrators of the social media groups who kindly allowed recruitment adverts to be posted on their sites. They thank the women who took part for their time and candour, without whom this study would not have been possible. They also thank the reviewers for their helpful and constructive comments on their manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @amyjanethompson, @drlauraljones

Contributors: AJT conceived the study and designed it in collaboration with LLJ. AJT conducted and transcribed the interviews and he also coded the data. Initial drafts of the manuscript were written by AJT, which were reviewed and edited by LLJ and AET. All authors contributed to analysis and interpretation and also read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was sought and a favourable decision obtained from the University of Birmingham Internal Ethics Review Committee (ref: IREC2017/1319061). All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the risk of compromising the individual privacy of participants, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016;387:475–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016;387:491–504. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01044-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation Breastfeeding. Available: https://www.who.int/topics/breastfeeding/en/ [Accessed 10 Jan 2019].

- 4.Stearns CA. Cautionary tales about extended breastfeeding and weaning. Health Care Women Int 2011;32:538–54. 10.1080/07399332.2010.540051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAndrew F, Thompson J, Fellows L, et al. Infant feeding Survery 2010, 2012. Available: http://doc.ukdataservice.ac.uk/doc/7281/mrdoc/pdf/7281_ifs-uk-2010_report.pdf [Accessed 10 Jan 2019].

- 6.Dowling S, Pontin D. Using liminality to understand mothers' experiences of long-term breastfeeding: 'Betwixt and between', and 'matter out of place'. Health 2017;21:57–75. 10.1177/1363459315595846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS England Maternity and breastfeeding statistics. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/maternity-and-breastfeeding/ [Accessed 10 Jan 2019].

- 8.Scottish Maternal and Infant Nutrition Surgery Scottish maternal and infant nutrition surgery 2017, 2018. Available: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/statistics-publication/2018/02/scottish-maternal-infant-nutrition-survey-2017/documents/00531610-pdf/00531610-pdf/govscot%3Adocument [Accessed 10 Jan 2019].

- 9.Pokhrel S, Quigley MA, Fox-Rushby J, et al. Potential economic impacts from improving breastfeeding rates in the UK. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:334–40. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen K. Breastfeeding: a smart investment in people and in economies. Lancet 2016;387:416. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00012-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Acceptable medical reasons for use of breast-milk substitutes, 2009. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/69938/WHO_FCH_CAH_09.01_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 10 Jan 2019]. [PubMed]

- 12.Kukla R. Ethics and ideology in breastfeeding advocacy campaigns. Hypatia 2006;21:157–80. 10.1111/j.1527-2001.2006.tb00970.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cattaneo A. Academy of breastfeeding medicine founder's lecture 2011: inequalities and inequities in breastfeeding: an international perspective. Breastfeed Med 2012;7:3–9. 10.1089/bfm.2012.9999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheeshka J, Potter B, Norrie E, et al. Women's experiences breastfeeding in public places. J Hum Lact 2001;17:31–8. 10.1177/089033440101700107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer K. The emotional resonances of breastfeeding in public: the role of strangers in breastfeeding practice. Emot Space Soc 2018;26:33–40. 10.1016/j.emospa.2016.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauck YL, Irurita VF. Incompatible expectations: the dilemma of breastfeeding mothers. Health Care Women Int 2003;24:62–78. 10.1080/07399330390170024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckley KM. Beliefs and practices related to extended breastfeeding among La Leche League mothers. J Perinat Educ 1992;1:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowling S, Brown A. An exploration of the experiences of mothers who breastfeed long-term: what are the issues and why does it matter? Breastfeed Med 2013;8:45–52. 10.1089/bfm.2012.0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faircloth CR. ‘If they want to risk the health and well-being of their child, that's up to them’: Long-term breastfeeding, risk and maternal identity. Health Risk Soc 2010;12:357–67. 10.1080/13698571003789674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faircloth C. ‘What Science Says is Best’: Parenting Practices, Scientific Authority and Maternal Identity. Sociol Res Online 2010;15:85–98. 10.5153/sro.2175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman KL, Williamson IR. Why aren't you stopping now?!' Exploring accounts of white women breastfeeding beyond six months in the East of England. Appetite 2018;129:228–35. 10.1016/j.appet.2018.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britten N, Jones R, Murphy E, et al. Qualitative research methods in general practice and primary care. Fam Pract 1995;12:104–14. 10.1093/fampra/12.1.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leeming D, Marshall J, Locke A. Understanding process and context in breastfeeding support interventions: the potential of qualitative research. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13:e12407. 10.1111/mcn.12407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dicicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ 2006;40:314–21. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. London: Sage Publications, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of Grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brockway M, Venturato L. Breastfeeding beyond infancy: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2016;72:2003–15. 10.1111/jan.13000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendall-Tackett KA, Sugarman M. The social consequences of long-term breastfeeding. J Hum Lact 1995;11:179–83. 10.1177/089033449501100316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gribble KD. Long-Term breastfeeding; changing attitudes and overcoming challenges. Breastfeeding Rev 2008;16:5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lo Iacono V, Symonds P, Brown DHK. Skype as a tool for qualitative research interviews. Sociol Res Online 2016;21:103–17. 10.5153/sro.3952 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trier-Bieniek A. Framing the telephone interview as a participant-centred tool for qualitative research: a methodological discussion. Qualitative Research 2012;12:630–44. 10.1177/1468794112439005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger R. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research 2015;15:219–34. 10.1177/1468794112468475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drake P. Grasping at methodological understanding: a cautionary tale from insider research. Int J Res Meth Educ 2010;33:85–99. 10.1080/17437271003597592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faircloth C. ‘Natural’ Breastfeeding in Comparative Perspective: Feminism, Morality, and Adaptive Accountability. Ethnos 2017;82:19–43. 10.1080/00141844.2015.1028562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faircloth C. “Culture means nothing to me”: Thoughts on nature/culture in narratives of long-term breastfeeding. Cambridge Anthropol 2008;28:63–84. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowlby J. Attachment. London: Pelican, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sears W, Sears M. The attachment parenting book. Massachusetts: Little, Brown and Company, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller PM, Commons ML. The benefits of attachment parenting for infants and children: a behavioral developmental view. Behav Dev Bull 2010;16:1–14. 10.1037/h0100514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van den Berg M, Ball HL, Practices BHL. Practices, advice and support regarding prolonged breastfeeding: a descriptive study from Sri Lanka. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2008;26:229–43. 10.1080/02646830701691376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hauck FR, Thompson JMD, Tanabe KO, et al. Breastfeeding and reduced risk of sudden infant death syndrome: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2011;128:103–10. 10.1542/peds.2010-3000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) Addendum to clinical guideline 37, postnatal care, 2014. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg37/evidence/cg37-postnatal-care-full-guideline-addendum2 [Accessed 9 Sep 2019]. [PubMed]

- 45.Dettwyler KA. A time to Wean: the hominid blueprint for the natural age of weaning in modern human populations. in Stuart-Macadam : Breastfeeding: biocultural perspectives. New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1995: 39–73. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dettwyler KA. When to wean: biological versus cultural perspectives. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2004;47:712–23. 10.1097/01.grf.0000137217.97573.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035199supp001.pdf (43.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035199supp002.pdf (50.5KB, pdf)