Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is associated with a prothrombotic state in infected patients. After presenting a case of right ventricular thrombus in a patient with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), we discuss the unique challenges in the evaluation and treatment of COVID-19 patients, highlighting our COVID-19–modified pulmonary embolism response team algorithm. (Level of Difficulty: Beginner.)

Key Words: clot in transit, pulmonary embolism, right ventricle, thrombus, vascular disease

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID-19, coronavirus disease-2019; CTA, computed tomography angiography; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; Pao2, partial arterial pressure of oxygen; PE, pulmonary embolism; PERT, pulmonary embolism response team; PPE, personal protective equipment; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; VTE, venous thromboembolism

Graphical abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is associated with a prothrombotic state in infected patients. After presenting a case of right ventricular…

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19)–related critical illness and multiorgan dysfunction in a subset of those infected (1). Those who develop critical illness may experience a hypercoagulable state and, in extreme cases, disseminated intravascular coagulation (2,3). Investigators from Wuhan, China, have reported finding microthrombi in the pulmonary vasculature of patients on autopsy (4). Previously, select patients with SARS-CoV-1 displayed diffuse pulmonary microthrombi and cases of overt pulmonary embolism (PE), suggesting this class of virus may predispose to coagulation disorders (5). More recent reports suggest cases of overt PE in COVID-19 patients (6, 7, 8). Furthermore, research by Dutch and Chinese investigators has suggested a rate approaching 30% for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in critically ill patients (9,10). The Computerized Registry of Patients with Venous Thromboembolism (RIETE) has reported a total of >300 COVID-19 patients from Europe to date who were diagnosed with VTE; it is not known, however, if this exceeds the expected incidence of VTE in critically ill patients (Dr. Manual Monreal, personal communication, April 2020).

Learning Objectives

-

•

To understand clinical findings that may prompt further diagnostic evaluation for VTE in critically ill COVID-19 patients.

-

•

To explore treatment options for COVID-19 patients with VTE.

-

•

To understand the unique challenges in diagnosis and treatment of VTE in patients with COVID-19.

Given this increased potential for hypercoagulable events, yet being mindful of exposure risks and practical considerations in caring for COVID-19 patients, we present a COVID-19 patient with clot in transit, along with an algorithm for diagnosing and treating VTE in COVID-19 patients.

History of Presentation

A 44-year-old man was admitted after 2 days of shortness of breath and nonproductive cough. Upon presentation, the patient had a temperature of 99.3°F, heart rate of 152 beats/min, blood pressure of 102/84 mm Hg, and a respiratory rate of 44 breaths/min. He was hypoxic with a peripheral oxygenation saturation of 86%, while breathing 6 l/min of supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula with an additional 15 l/min applied by non-rebreather mask.

Medical History

The patient’s medical history was notable only for obesity (body mass index 31 kg/m2) and type 2 diabetes.

Differential Diagnosis

The primary differential diagnosis for the patient’s presentation includes bacterial pneumonia, viral upper or lower respiratory tract infection, and PE. Given the patient’s age, few medical comorbidities, and the significant community spread of SARS-CoV-2 virus, COVID-19 illness was the most likely diagnosis.

Investigations

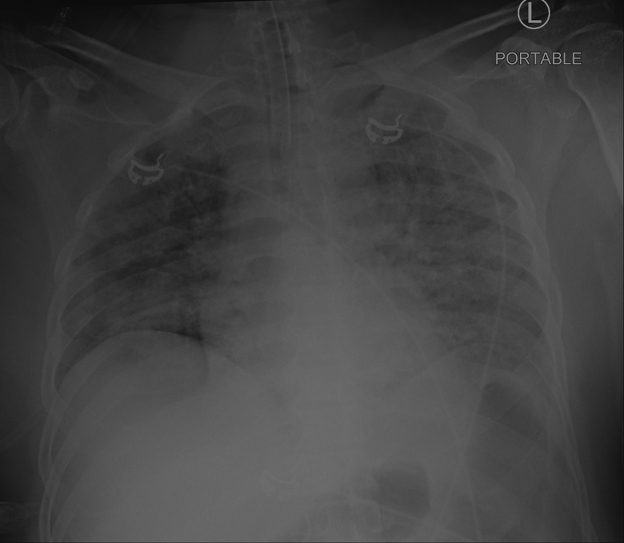

The patient’s chest radiograph revealed diffuse bilateral hazy opacities (Figure 1). Results of the SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab polymerase chain reaction test were positive. Initial venous blood gas analyses were significant for a pH of 7.09, partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide 41 mm Hg, and partial arterial pressure of oxygen (Pao2) 33 mm Hg with a lactate level of 12 mmol/l. After intubation, the patient’s arterial blood gas analysis improved slightly to pH 7.14, partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide 53 mm Hg, and Pao2 193 mm Hg with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 100%. The Pao2:fraction of inspired oxygen ratio of 193, along with his chest radiograph findings of diffuse bilateral hazy opacities, was consistent with moderate acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (11). The patient’s initial laboratory studies (Table 1) were most notable for a white blood cell count of 27.8 × 103/μl and serum creatinine of 1.88 mg/dl. His high-sensitivity troponin-T level was initially 46 ng/l, with a subsequent value of 154 ng/l; N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide was 14,535 pg/ml, ferritin was 3,495 ng/l, and D-dimer was >20 μg/ml (upper limit of detection).

Figure 1.

Chest Radiograph Demonstrating Bilateral Opacities Indicative of ARDS

Anterior posterior portable chest radiograph with fluffy bilateral infiltrates significant for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to coronavirus disease-2019 illness.

Table 1.

Laboratory Values and Normal Ranges for the Described Case

| Patient Value | Normal Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Venous blood gas, initial | ||

| pH | 7.09 | 7.36–7.41 |

| Paco2, mm Hg | 53 | 40–45 |

| Pao2, mm Hg | 33 | 30–49 |

| Lactate, mmol/l | 12 | 0.5–2.2 |

| Arterial blood gas, subsequent | ||

| pH | 7.14 | 7.35–7.45 |

| Paco2, mm Hg | 53 | 32–45 |

| Pao2, mm Hg | 193 | 72-104 |

| Pao2:Fio2 | 193 | >300 |

| Complete blood count, initial | ||

| White blood cell count, × 103/dl | 27.8 | 3.12–8.44 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 15.9 | 12.6–17.0 |

| Platelets, × 103/μl | 471 | 156–325 |

| Chemistries, cardiac, and Inflammatory biomarkers (initial unless otherwise specified) | ||

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.88 | 0.7–1.3 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.8 | 3.9–5.2 |

| High-sensitivity troponin-T, initial, ng/l | 46 | ≤22 |

| High-sensitivity troponin-T, subsequent, ng/l | 154 | ≤22 |

| N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, pg/ml | 14,535 | 0.0–138.0 |

| Ferritin, ng/l | 3,495 | 30.0–400.0 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/ml | 5.89 | ≤0.08 |

| High sensitivity C-reactive protein, mg/l | >300 | 0.0–10.0 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, mm/h | 97 | 0–15 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/l | 1,468 | 135–225 |

| D-dimer, μg/ml | >20.0 | ≤0.8 |

| Prothrombin time, s | 17.0 | 11.9–14.4 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, s | 27.6 | 23.9–34.7 |

Fio2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; Paco2 = partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; Pao2= partial arterial pressure of oxygen.

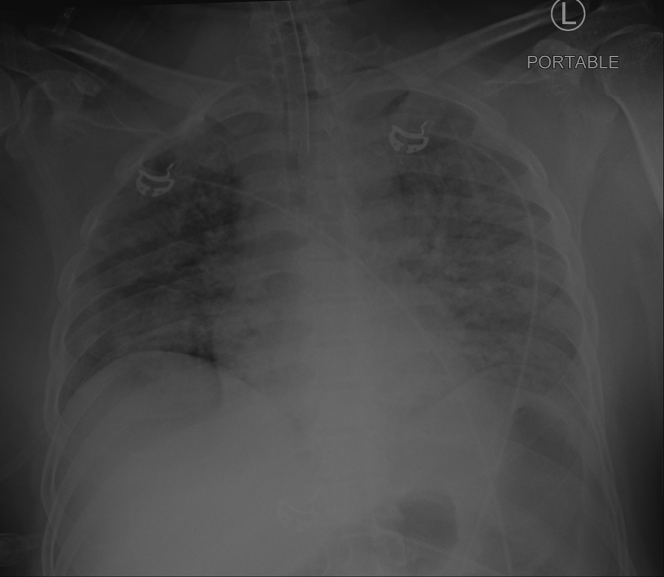

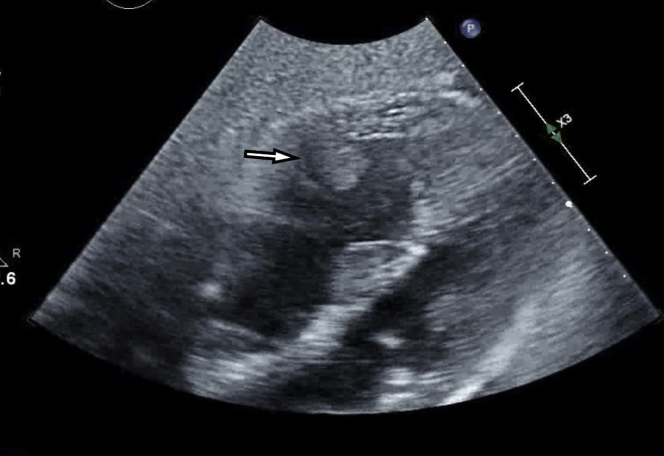

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was obtained given the severity of hypoxemia, hemodynamic instability, and elevated D-dimer out of concern for acute PE. The TTE revealed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45% with global hypokinesis, and a moderate to severely dilated right ventricle with moderate to severely reduced right ventricular systolic function (Video 1). There was a flattening of the interventricular septum throughout the cardiac cycle consistent with both pressure and volume overload of the right ventricle. Additionally noted was a 1.5 × 1.7 cm well-circumscribed mobile echodensity attached to the right ventricular free wall concerning for clot in transit (Figure 2).

Online Video 1.

Right Ventricular Clot in Transit

Subcostal view on transthoracic echocardiogram. The right ventricle is enlarged with severe dysfunction. There is a thrombus attached to the mid-right ventricle free wall.

Figure 2.

Thrombus Visualized in the Mid–Right Ventricle

Subcostal view on transthoracic echocardiogram. The right ventricle is enlarged, and there is a thrombus adherent to the free wall of the mid–right ventricle.

Management

The patient was intubated for hypoxemic respiratory failure and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). During the patient’s initial course in the ICU, he became progressively hypotensive over the course of the first 6 h, requiring maximum doses of norepinephrine (40 μg/min) and vasopressin (2.4 U/h). Given his progressive shock in the setting of high inflammatory markers, he was started on 1 mg/kg of intravenous methylprednisolone per day. A TTE was obtained with the resultant findings described earlier. Given these findings, the pulmonary embolism response team (PERT) was consulted, and the patient was administered 100 mg (over 2 h) of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and systemic anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin once the tPA infusion was complete. The patient was started on a dobutamine infusion for inotropic support and considered for venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in case his hemodynamic condition worsened.

After administration of tPA, the patient was weaned off pressors within 24 h. He was subsequently weaned off inotropic support over the ensuing 3 days. His repeat TTE revealed normal left ventricular systolic function and mild dilation of the right ventricle with preserved right ventricular systolic function. The previously observed clot in transit was no longer visualized, and right ventricular function was improving (Video 2). Bilateral lower extremity venous Doppler ultrasounds were negative for deep vein thrombosis. The patient had no immediate bleeding complications after administration of tPA.

Online Video 2.

Post–Tissue Plasminogen Activator Treatment of the Right Ventricle

Discussion

The usual risk stratification schema for acute PE rely on a combination of hemodynamic clinical parameters, such as hypoxemia, tachycardia, and hypotension along with serum biomarkers, such as troponin or brain natriuretic peptide, followed by confirmatory imaging tests (12). Severe COVID-19–related ARDS may present with many similar hemodynamic and biomarker derangements masking underlying VTE. Furthermore, the usual imaging modalities for PE may not be routinely performed given the resource constraints imposed by crisis and the need to minimize exposure to the patient, requisite personal protective equipment (PPE), and the transport required. PERT teams, as multidisciplinary collaborations, are poised to provide guidance on the diagnosis and management of VTE in the setting of severe COVID-19 illness.

The combined effects of the systemic inflammatory response and immobilization during hospital stay make VTE an important item on the list of differential diagnoses. There are no currently accepted risk scores for the prediction of significant PE in the context of severe COVID-19 illness. This makes clinical suspicion an important aspect of decision-making regarding further testing or empirical treatment. In general, unexplained hypoxemia above what is expected for the severity of ARDS, unexplained right heart failure, or a severely elevated D-dimer may prompt further testing in the right clinical setting.

Diagnostic Laboratory Tests and Imaging

In lieu of computed tomography angiography (CTA) or ventilation-perfusion scanning to detect PE, other modalities may be used as surrogates to help in the decision of whether to start therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in COVID-19 patients. Duplex compression ultrasound of the upper and lower extremities can detect deep vein thrombosis with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity in patients with significant extremity swelling (13).

TTE can detect pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction. A focused bedside TTE may supply information regarding signs of right ventricular strain, diminished right ventricular function, or right ventricular/left ventricular ratio >1. These markers may be consistent with a clinically significant PE (12). An extremity duplex ultrasound examination and TTE may even be performed by the same clinical provider in the same clinical setting using a portable or handheld device as a bedside screen to limit exposure and PPE use.

Both troponin and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels may be elevated in the setting of severe COVID-19 illness. D-dimer elevations are also common and have been associated with significant prevalence of underlying VTE (14). Another potential risk stratification tool would be the sepsis-induced coagulopathy score, which uses common clinical and laboratory values to identify subsets of higher risk patients. A sepsis-induced coagulopathy score >4 is associated with worse outcomes at 28 days (15).

Diagnostic CTA remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of acute PE. Nonetheless, exceptional circumstances specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as potential infection of clinical or ancillary staff by a patient with poorly controlled cough and refractory hypoxemia limiting patient transport, may make empirical anticoagulation preferable to CTA or ventilation-perfusion scanning. The clinical team should always carefully balance the risks and benefits of empirical anticoagulation without objective imaging. CTA should be performed at the discretion of the treating team, and if needed after discussion with the PERT team, so that considerations can be made based on feasibility and safety of performing the confirmatory test versus the risk of empirical treatment under these conditions.

Treatment

Patients admitted to the hospital with COVID-19 critical illness should be given VTE prophylaxis as standard of care, unless contraindicated. Retrospective, observational data suggest a possible benefit to more intensive anticoagulation; however, this association should be verified in prospective randomized controlled trials before changing treatment algorithms, given the known risks associated with therapeutic anticoagulation (16).

The preferred anticoagulation for hemodynamically stable COVID-19 patients with proven VTE is enoxaparin 1 mg/kg subcutaneously twice daily (based on total body weight; maximum 196 kg). Using low-molecular-weight-heparin will reduce the use of PPE because routine monitoring with activated partial thromboplastin time or heparin assay is not necessary. Dose adjustment or the use of unfractionated heparin should be considered for those patients with reduced kidney function.

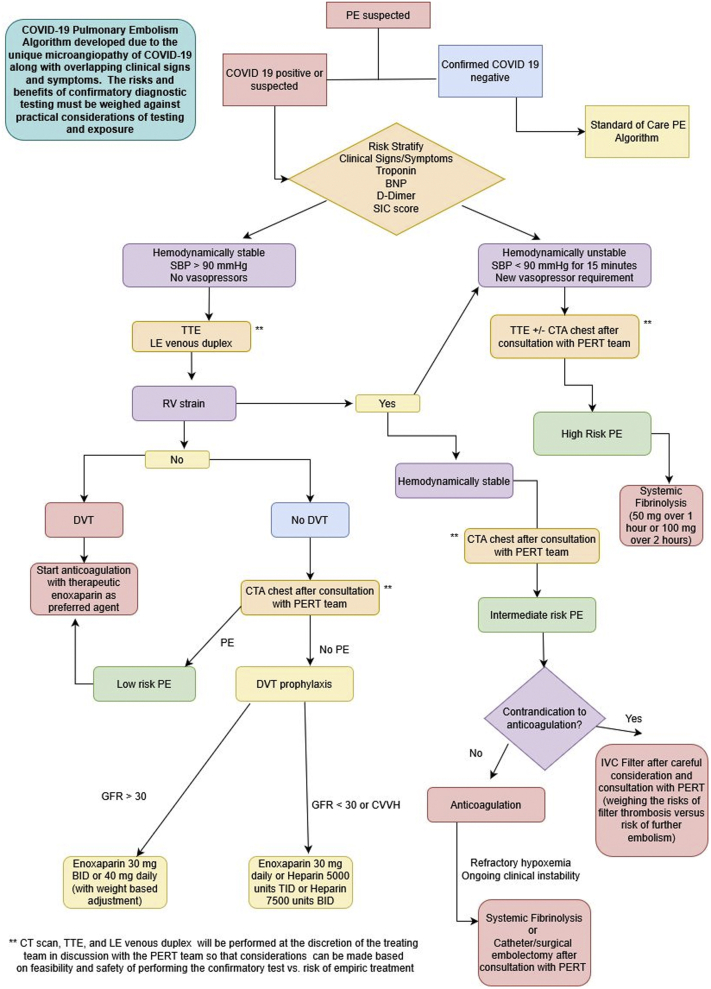

The roles for systemic thrombolysis, catheter or surgical thrombectomy, and ECMO have yet to be defined. We propose an algorithm that outlines our approach for testing and treatment for VTE in the setting of COVID-19 (Figure 3). (We note here that this algorithm is not a societal guideline but a product of consensus of PERT members at our institution.) Systemic thrombolysis remains a Class I recommendation for hemodynamically unstable PE (17). However, the hemodynamic effect of the underlying PE must be clinically distinguished from the systemic vasodilatory effects that may accompany COVID-19. In the setting of right heart strain, there have been limited anecdotal reports of success with catheter-based treatments. However, caution must be advised regarding resource utilization, including PPE, ICU beds, cardiac catheterization laboratories, and operating rooms. Similar considerations must be made for the use of ECMO in properly equipped centers.

Figure 3.

Suggested Algorithm for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism in COVID-19 Patients

Consensus algorithm determined by members of our institution’s (Columbia University Irving Medical Center) pulmonary embolism response (PERT) team. (Please note: This algorithm is not a societal guideline.) BID = twice daily; BNP = B-type natriuretic peptide; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease-2019; CTA = computed tomography angiography; DVT = deep vein thrombosis; IVC = inferior vena cava; LE = lower extremity; PE = pulmonary embolism; PERT = pulmonary embolism response team; RV = right ventricular; SBP= systolic blood pressure; SIC = sepsis-induced coagulopathy; TID = 3 times daily; TTE = transthoracic echocardiography.

In our case, the patient had severe right ventricular dysfunction with a large clot in transit. Although surgical or catheter-based options were considered, the hemodynamic profile and low bleeding risk suggested that systemic thrombolysis would be the optimal approach. This approach led to dramatic improvement in the patient’s hemodynamic profile. We used the standard dose of 100 mg due to the significant right ventricular strain suggesting concomitant PE, the patient’s critical illness, and the low bleeding risk. Because a confirmed VTE was visualized on echocardiogram, tPA was a reasonable therapy. Right ventricular dysfunction in the absence of confirmed VTE is clinical conundrum that requires careful balancing of the risks and benefits of systemic thrombolysis before use but is generally discouraged.

Follow-Up

On post-tPA day 5, the patient was noted to have bleeding within the oropharynx, which ultimately required compression packing to allow for continued systemic anticoagulation, which has since been removed. He remains off of vasoactive medications and is making progress toward extubation. The patient remains hospitalized as of this writing, but the plan is to continue oral anticoagulation for at least 3 to 6 months after discharge.

Conclusions

We present a case of a clot in transit during COVID-19 critical illness. COVID-19 seems to be associated with an increased propensity for thromboembolic disease. Heightened suspicion is necessary to clinically detect VTE in this disease and treat accordingly, while mindful of the inherent risks to health-care workers and resources available, depending on the level of crisis, in the overall health system.

Footnotes

Dr. Sethi has received honoraria from Chiesi, Inc. and Janssen. Dr. Brodie has received research support from ALung Technologies; and has been on the medical advisory boards for ALung Technologies, Baxter, Breethe, Xenios, and Hemovent. Dr. Kirtane has received institutional funding to Columbia University and/or the Cardiovascular Research Foundation from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, CSI, CathWorks, Siemens, Philips, and ReCor Medical; and has received research grants, institutional funding includes fees paid to Columbia University and/or the Cardiovascular Research Foundation for speaking engagements and/or has received consulting (no speaking/consulting fees were personally received and with travel/meal reimbursements only). Dr. Parikh has received institutional grants/research support from Abbott Vascular, Shockwave Medical, TriReme Medical, and Surmodics; consulting fees from Terumo and Abiomed; and has served on advisory boards for Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, CSI, Janssen, and Philips. Dr. Rosenzweig has received research funding from Janssen/Actelion, Bayer, Gilead, Lung Rx, and SonVie. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Case Reportsauthor instructions page.

Appendix

For supplemental videos, please see the online version of this paper.

References

- 1.Siddiqi H.K., Mehra M. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical-therapeutic staging proposal. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2020;39:405–407. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thachil J., Tang N., Gando S. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1023–1026. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo W., Yu H., Gou J. Clinical pathology of critical patient with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) Preprints. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng K.H., Wu A.K., Cheng V.C. Pulmonary artery thrombosis in a patient with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:e3. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.030049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie Y., Wang X., Yang P., Zhang S. COVID-19 complicated by acute pulmonary embolism. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020 Mar 16 doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200067. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danzi G.B., Loffi M., Galeazzi G., Gherbesi E. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1858. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ullah W., Saeed R., Sarwar U., Patel R., Fischman D.L. COVID-19 complicated by acute pulmonary embolism and right-sided heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2020;2:1379–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivera-Lebron B., McDaniel M., Ahrar K. Diagnosis, treatment and follow up of acute pulmonary embolism: consensus practice from the PERT Consortium. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019;25 doi: 10.1177/1076029619853037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates S.M., Jaeschke R., Stevens S.M. Diagnosis of DVT: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(Suppl 2):e351S–e418S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iba T., Nisio M.D., Levy J.H., Kitamura N., Thachil J. New criteria for sepsis-induced coagulopathy (SIC) following the revised sepsis definition: a retrospective analysis of a nationwide survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konstantinides S.V., Meyer G., Becattini C. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2019;54:1–68. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]