Abstract

Introduction

Family caregivers (FCGs) play an integral, yet often invisible, role in the Canadian health-care system. As the population ages, their presence will become even more essential as they help balance demands on the system and enable community-dwelling seniors to remain so for as long as possible. To preserve their own well-being and capacity to provide ongoing care, FCGs require support to the meet the challenges of their daily caregiving responsibilities. Supporting FCGs results in better care provision to community-dwelling seniors receiving health-care services, as well as enhancing the quality of life for FCGs. Although FCGs rely upon health-care professionals (HCPs) to provide them with support and services, there is a paucity of research pertaining to the type of health workforce training (HWFT) that HCPs should receive to address FCG needs. Programs that train HCPs to engage with, empower, and support FCGs are required.

Objective

To describe and discuss key findings of a caregiver symposium focused on determining components of HWFT that might better enable HCPs to support FCGs.

Methods

A one-day symposium was held on February 22, 2018 in Edmonton, Alberta, to gather the perspectives of FCGs, HCPs, and stakeholders. Attendees participated in a series of working groups to discuss barriers, facilitators, and recommendations related to HWFT. Proceedings and working group discussions were transcribed, and a qualitative thematic analysis was conducted to identify key themes.

Results

Participants identified the following topic areas as being essential to training HCPs in the provision of support for FCGs: understanding the FCG role, communicating with FCGs, partnering with FCGs, fostering FCG resilience, navigating healthcare systems and accessing resources, and enhancing the culture and context of care.

Conclusions

FCGs require more support than is currently being provided by HCPs. Training programs need to specifically address topics identified by participants. These findings will be used to develop HWFT for HCPs.

Keywords: family caregiving, caregiver, health workforce training, competencies

INTRODUCTION

The Canadian population is aging rapidly. For the first time in Canadian census history, the population over age 65 exceeds that of children under 15 years of age.(1) By 2035, 20% of Canadians will be over age 65.(2) While medical advances and a focus on prevention have resulted in more fit and healthy older adults, current projections suggest that health gains will stabilize and likely decrease as people live longer into old age.(3) Thus, care needs are expected to increase significantly, leaving upcoming generations with responsibilities for which they may not be prepared.(4)

Family caregivers (FCG)—individuals who take on an unpaid role providing emotional, physical or practical support in response to an illness, disability or age-related need—tend to 80% of seniors’ care needs.(5,6) In 2007, FCGs provided 1.5 billion hours of care, equivalent to the work hours of 1.2 million full-time employees.(4) Currently, 5.9 million Canadians are FCGs for an older adult.(4) In the years ahead, it is expected that smaller families, the involvement of women in the workforce, geographical separation, and divorce will reduce the number of FCGs.(7,8)

Although some positive outcomes related to caregiving have been documented, FCGs more frequently experience significant caregiver burden(9) and costs to their own well-being.(9,10) This is especially true for those providing over 20 hours of care weekly, or when employment or child-rearing demands compound their workload.(7,8,11) A third of FCGs of home care clients report feeling distressed; up from 16% in 2010.(12,13) Further, FCGs are often marginalized by existing health-care systems(14) and their personal needs frequently go unmet.(15)

Notwithstanding, the plethora of national reports recommending fundamental changes in the way FCGs are identified, assessed, and supported, the health workforce continues to focus on patient needs rather than those of FCGs.(10,11) FCGs rely on health-care providers (HCPs), such as physicians, nurses, social workers, and occupational therapists, to provide services, yet there is a paucity of literature on education HCPs receive about FCGs and factors that may prevent or enable the provision of adequate support.(10,16–18)

To address this gap, we aimed to identify barriers and facilitators faced by HCPs in supporting FCGs, as well as knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed by HCPs to provide comprehensive services to FCGs. Importantly, FCGs themselves were engaged in identifying requisite HCP competencies in this practice area.(10) Emergent themes from this study will inform the development of a competency framework and health workforce training (HWFT) curricula aimed at enabling HCPs to provide better caregiver-centered care. It is envisioned that such competency-based, caregiver-centred care curricula will underpin standards for licensure, certification, and service delivery to FCGs.(12,16,19)

METHODS

A one-day Health-care Workforce Training in Supporting Family Caregivers of Seniors in Care symposium was held February 22, 2018 in Edmonton, Alberta, to engage multi-level, interdisciplinary stakeholders and FCGs in discussions around gaps in services available to FCGs and HWFT that might better equip HCPs to support FCGs. The symposium was the fourth in a series sponsored by Edmonton’s Covenant Health’s Network of Excellence in Seniors’ Health and Wellness. Focused on family caregivers, the preceding symposia were: Supporting Family Caregivers of Seniors: Improving Care and Caregiver Outcomes (2014); Supporting Family Caregivers of Seniors within Acute and Continuing Care Systems (2016); and Fostering Resilience in Family Caregivers of Seniors in Care (2017).(10, 20–22) Sixty multi-level interdisciplinary participants from the previous symposia were invited to register.

Prior to the symposium, participants were provided with the 2016 and 2017 FCG symposia reports, a literature review, and an environmental scan of HWFT. A survey was also distributed pre-symposium to gain information about key areas in which to support FCGs, and the learning needs of HCPs specific to supporting FCGs. Survey questions focused on communication between HCPs and FCGs, assessment of FCG needs, health system navigation, access to resources, health system culture change, and organizational support for HCP training.

On the day of the symposium, participants were presented with information about health workforce support. Facilitated 60-minute working groups followed, which focused on assessment of caregiver needs, culture change, communication, system navigation and access to resources, and organizational support. Written consent was obtained prior to the symposium, and working group sessions were recorded and transcribed. An evaluation form was distributed post-symposium via email and responses were collated.

Participants

Twenty-nine people responded to the pre-symposium survey and 40 individuals participated in the one-day symposium including FCGs (n=8), frontline HCPs (n=6), managers (n=3), senior services organizers (n=3), non-governmental organization leaders (n=6), academics (n=11), and policy-makers (n=3). Although we categorized participants by primary role, many had more than one role. Over half of the participants indicated that they were FCGs, and several academics were also practising professionals including several physicians, a nurse, a social worker and an occupational therapist.

Data Analysis

The authors have a realist theoretical perspective, which assumes that there is an external reality which can be observed and studied empirically.(23) The researchers do not suppress individual background and experiences; rather, experience provides a more substantive approach to analysis and theory refinement. Aligned with this perspective, thematic analysis of working group findings and evaluations followed Braun and Clarke’s qualitative methodology, and included both deductive and inductive approaches.(24) This included immersion in, and review of, transcripts of the working group proceedings (RF) to identify key emergent themes. Structured categories were initially imposed on the data by two of the authors (RF, SBP) to organize findings into barriers, facilitators, and recommendations associated with HWFT and topics discussed in the focus groups. This deductive approach identified current practices and actionable changes relevant to HWFT. Preliminary analytical notes facilitated refinement of open axial coding. Themes were then iteratively modified to ensure that they accurately captured the codes, were supported by the data, made sense, and were distinct. Further inductive analysis and validation was supported by five of the authors (SBP, JP, WD, WJ and SA) informed by Rachael Fisher’s preliminary analysis.

Using the research questions as a lens, the transcripts were reviewed line by line and codes were assigned to segments of text to identify emerging themes. This process was recursive, and involved alternating back and forth between data analysis and reading of the literature to derive prominent themes from the data. The collaborative approach to inductive analysis enables researchers to enrich interpretation, as well as evaluate individual interpretations and biases.(23) This combined inductive and deductive collaborative approach enhanced analytical rigour and trustworthiness of the data. NVivo 11 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) was used to categorize data by topic for further exploration and thematic development.

RESULTS

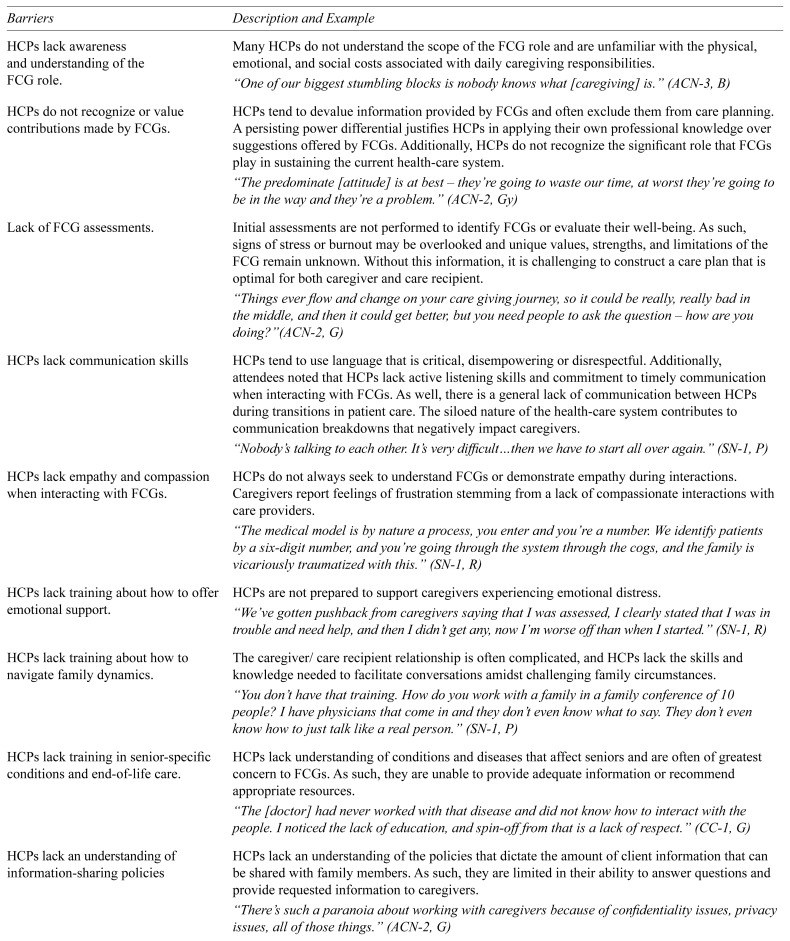

Symposium participants identified facilitators and barriers to care provision to FCGs by HCPs. Facilitators included well-meaning professionals, increased awareness of and attention to FCGs, the availability of client-centred care curricula and community services, access to providers specialized in system navigation, the recognized need for health-care culture change, and promotion of resilience-building practices. Barriers included a lack of awareness and undervaluing of FCGs, system fragmentation and structural demands, engrained HCP practices and attitudes, policies limiting information-sharing with FCGs, a lack of FCG assessments, poor communication, a paucity of HWFT regarding the delivery of emotional support to FCGs and navigation of family dynamics, and inadequate knowledge of conditions impacting older adults (See themes in Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Barriers and facilitators to caregiver-centered care

| Barriers | Description and Example |

|---|---|

| HCPs lack awareness and understanding of the FCG role. | Many HCPs do not understand the scope of the FCG role and are unfamiliar with the physical, emotional, and social costs associated with daily caregiving responsibilities. “One of our biggest stumbling blocks is nobody knows what [caregiving] is.” (ACN-3, B) |

| HCPs do not recognize or value contributions made by FCGs. | HCPs tend to devalue information provided by FCGs and often exclude them from care planning. A persisting power differential justifies HCPs in applying their own professional knowledge over suggestions offered by FCGs. Additionally, HCPs do not recognize the significant role that FCGs play in sustaining the current health-care system. “The predominate [attitude] is at best – they’re going to waste our time, at worst they’re going to be in the way and they’re a problem.” (ACN-2, Gy) |

| Lack of FCG assessments. | Initial assessments are not performed to identify FCGs or evaluate their well-being. As such, signs of stress or burnout may be overlooked and unique values, strengths, and limitations of the FCG remain unknown. Without this information, it is challenging to construct a care plan that is optimal for both caregiver and care recipient. “Things ever flow and change on your care giving journey, so it could be really, really bad in the middle, and then it could get better, but you need people to ask the question – how are you doing?”(ACN-2, G) |

| HCPs lack communication skills | HCPs tend to use language that is critical, disempowering or disrespectful. Additionally, attendees noted that HCPs lack active listening skills and commitment to timely communication when interacting with FCGs. As well, there is a general lack of communication between HCPs during transitions in patient care. The siloed nature of the health-care system contributes to communication breakdowns that negatively impact caregivers. “Nobody’s talking to each other. It’s very difficult…then we have to start all over again.” (SN-1, P) |

| HCPs lack empathy and compassion when interacting with FCGs. | HCPs do not always seek to understand FCGs or demonstrate empathy during interactions. Caregivers report feelings of frustration stemming from a lack of compassionate interactions with care providers. “The medical model is by nature a process, you enter and you’re a number. We identify patients by a six-digit number, and you’re going through the system through the cogs, and the family is vicariously traumatized with this.” (SN-1, R) |

| HCPs lack training about how to offer emotional support. | HCPs are not prepared to support caregivers experiencing emotional distress. “We’ve gotten pushback from caregivers saying that I was assessed, I clearly stated that I was in trouble and need help, and then I didn’t get any, now I’m worse off than when I started.” (SN-1, R) |

| HCPs lack training about how to navigate family dynamics. | The caregiver/care recipient relationship is often complicated, and HCPs lack the skills and knowledge needed to facilitate conversations amidst challenging family circumstances. “You don’t have that training. How do you work with a family in a family conference of 10 people? I have physicians that come in and they don’t even know what to say. They don’t even know how to just talk like a real person.” (SN-1, P) |

| HCPs lack training in senior-specific conditions and end-of-life care. | HCPs lack understanding of conditions and diseases that affect seniors and are often of greatest concern to FCGs. As such, they are unable to provide adequate information or recommend appropriate resources. “The [doctor] had never worked with that disease and did not know how to interact with the people. I noticed the lack of education, and spin-off from that is a lack of respect.” (CC-1, G) |

| HCPs lack an understanding of information-sharing policies | HCPs lack an understanding of the policies that dictate the amount of client information that can be shared with family members. As such, they are limited in their ability to answer questions and provide requested information to caregivers. “There’s such a paranoia about working with caregivers because of confidentiality issues, privacy issues, all of those things.” (ACN-2, G) |

| Barriers and facilitators to caregiver-centered care | HCPs experience tension between task-focused demands of their daily jobs and the desire to engage in person-centred care. The system tends to reward efficiency over interpersonal relationships, and HCPs do not have a means of recording time spent with FCGs for billing purposes. As such, HCPs feel limited in their ability to engage with FCGs. “There’s never enough time to do the communicating because they’re just overwhelmed with the tasks that they have to take within a short amount of time. It’s just a hindrance. Communication is a hindrance.” (C-1, Gy) |

| System fragmentation. | Supportive services exist, however, they are disconnected. HCPs lack an understanding of the system and are unable to assist FCGs as they attempt to navigate through different levels of care. As such, FCGs are unaware of resources and often unable to access beneficial services. A strong need for integration and communication between existing services was identified. “The system is broken, it’s all in pieces, so we need to fix it and help each other out.” (SN-1, B) |

| Engrained practices and attitudes within health-care settings. | Practices and attitudes that have long been embedded in health-care persist when they remain unexamined and unchallenged. Health-care workers tend to adopt the standards that are modelled in their workplace even when these engrained ways of doing do not facilitate adequate support for caregivers. “When you get to the root cause, people are really uncomfortable to do things differently.” (CC-1, Gy) |

|

| |

| Facilitators | |

|

| |

| The role of FCGs is increasingly recognized by the health-care system. | Attendees noted increasing awareness in society and government agencies of the vital role that FCGs play in caring for seniors. “…it’s documented how much money caregivers are putting into the system and saving the system, so it’s happening and now we need to protect them.” (C-2, B) |

| HCPs are well-intended. | HCPs generally have the desire to improve the quality of life of their clients by providing individualized care. “We go into health-care to help people.” (SN-1, P) |

| Person-centred care is being taught by post-secondary institutions. | Undergraduate and graduate level curricula introduce the concept of person-centred care and teach strategies for implementing key principles. “[Education] is encompassed in person-centred care philosophies, so you’re not just looking at the patient, you’re looking at the whole picture.” (ACN-3, G) |

| Existing and emerging resilience-building programs. | There is a wide body of research regarding resilience which may inform program development aimed at increasing caregiver resilience. “[Certain] organizations already have a template for that…so there are pockets of things happening.” (SN-3, P) |

| Health-care and social services exist. | Attendees identified services within Alberta that offer support for caregivers. Although adjustments need to be made to system organization, there is an existing structure upon which to build. “There are some parts of the system I think that do listen and help to facilitate things for caregivers. There are some good experiences.” (SN-2, B) |

| Certain HCPs are trained in system navigation. | Knowledgeable case managers and social workers within the system can assist FCGs with navigating the system. “In a social work job description is system navigator resource, like that is part of our role. Unfortunately, there’re not enough out there.” (SN-1, P) |

| Recognition of need for culture change within health-care organizations. | Professionals recognize that many health-care institutions have become unwelcoming and frightening environments for caregivers. “…[caregivers] don’t feel welcome. It’s not a welcoming environment.” (C-2, B) |

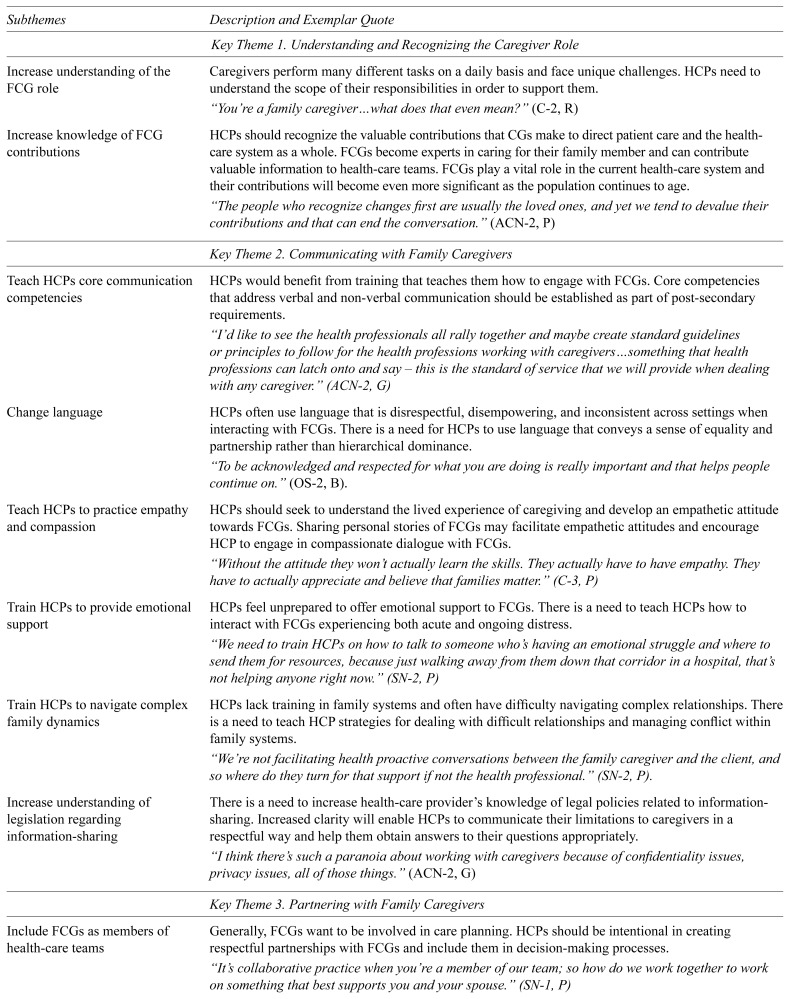

Stakeholders emphasized that HWFT is needed that involves competency development specific to supporting FCGs of older adults. Six competency development themes emerged from the data analysis: 1) understanding and recognizing the caregiver role; 2) communicating with FCGs; 3) partnering with FCGs; 4) fostering resilience among caregivers; 5) navigating health and social systems, and accessing resources; and 6) enhancing the culture and context of care (see Table 2). What follows is a description of each theme.

TABLE 2.

Key themes, subthemes, and descriptions for caregiver-centred care

| Subthemes | Description and Exemplar Quote |

|---|---|

| Key Theme 1. Understanding and Recognizing the Caregiver Role | |

|

| |

| Increase understanding of the FCG role | Caregivers perform many different tasks on a daily basis and face unique challenges. HCPs need to understand the scope of their responsibilities in order to support them. “You’re a family caregiver…what does that even mean?” (C-2, R) |

| Increase knowledge of FCG contributions | HCPs should recognize the valuable contributions that CGs make to direct patient care and the health-care system as a whole. FCGs become experts in caring for their family member and can contribute valuable information to health-care teams. FCGs play a vital role in the current health-care system and their contributions will become even more significant as the population continues to age. “The people who recognize changes first are usually the loved ones, and yet we tend to devalue their contributions and that can end the conversation.” (ACN-2, P) |

|

| |

| Key Theme 2. Communicating with Family Caregivers | |

|

| |

| Teach HCPs core communication competencies | HCPs would benefit from training that teaches them how to engage with FCGs. Core competencies that address verbal and non-verbal communication should be established as part of post-secondary requirements. “I’d like to see the health professionals all rally together and maybe create standard guidelines or principles to follow for the health professions working with caregivers…something that health professions can latch onto and say – this is the standard of service that we will provide when dealing with any caregiver.” (ACN-2, G) |

| Change language | HCPs often use language that is disrespectful, disempowering, and inconsistent across settings when interacting with FCGs. There is a need for HCPs to use language that conveys a sense of equality and partnership rather than hierarchical dominance. “To be acknowledged and respected for what you are doing is really important and that helps people continue on.” (OS-2, B). |

| Teach HCPs to practice empathy and compassion | HCPs should seek to understand the lived experience of caregiving and develop an empathetic attitude towards FCGs. Sharing personal stories of FCGs may facilitate empathetic attitudes and encourage HCP to engage in compassionate dialogue with FCGs. “Without the attitude they won’t actually learn the skills. They actually have to have empathy. They have to actually appreciate and believe that families matter.” (C-3, P) |

| Train HCPs to provide emotional support | HCPs feel unprepared to offer emotional support to FCGs. There is a need to teach HCPs how to interact with FCGs experiencing both acute and ongoing distress. “We need to train HCPs on how to talk to someone who’s having an emotional struggle and where to send them for resources, because just walking away from them down that corridor in a hospital, that’s not helping anyone right now.” (SN-2, P) |

| Train HCPs to navigate complex family dynamics | HCPs lack training in family systems and often have difficulty navigating complex relationships. There is a need to teach HCP strategies for dealing with difficult relationships and managing conflict within family systems. “We’re not facilitating health proactive conversations between the family caregiver and the client, and so where do they turn for that support if not the health professional.” (SN-2, P). |

| Increase understanding of legislation regarding information-sharing | There is a need to increase health-care provider’s knowledge of legal policies related to information-sharing. Increased clarity will enable HCPs to communicate their limitations to caregivers in a respectful way and help them obtain answers to their questions appropriately. “I think there’s such a paranoia about working with caregivers because of confidentiality issues, privacy issues, all of those things.” (ACN-2, G) |

|

| |

| Key Theme 3. Partnering with Family Caregivers | |

|

| |

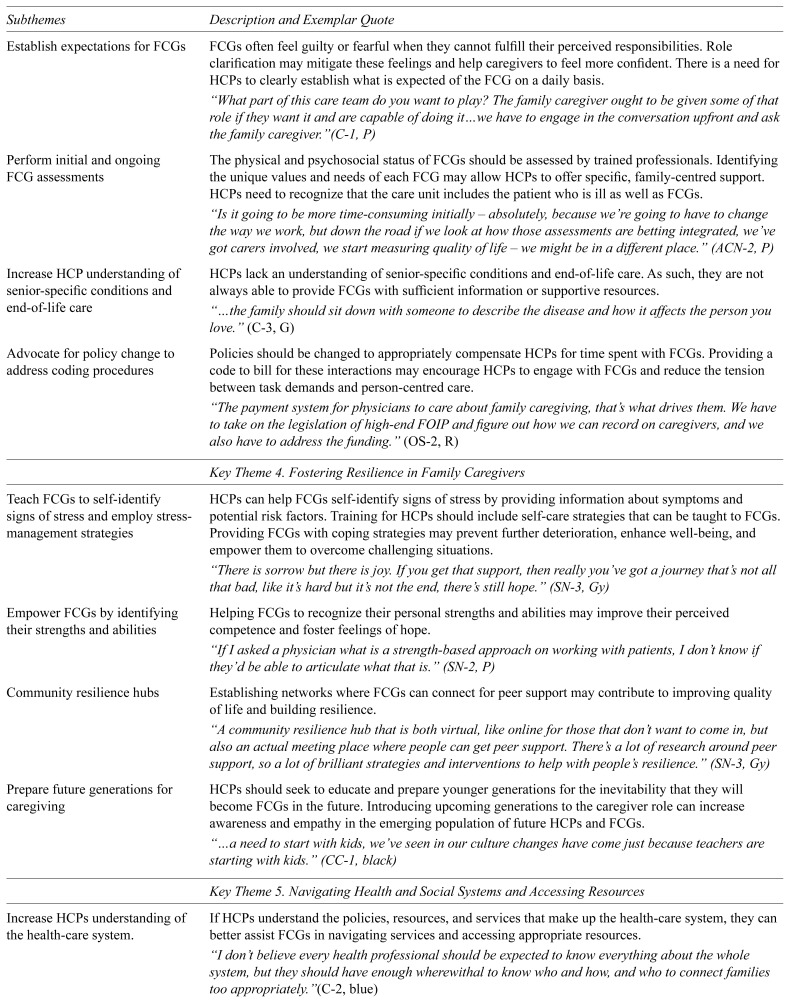

| Include FCGs as members of health-care teams | Generally, FCGs want to be involved in care planning. HCPs should be intentional in creating respectful partnerships with FCGs and include them in decision-making processes. “It’s collaborative practice when you’re a member of our team; so how do we work together to work on something that best supports you and your spouse.” (SN-1, P) |

| Establish expectations for FCGs | FCGs often feel guilty or fearful when they cannot fulfill their perceived responsibilities. Role clarification may mitigate these feelings and help caregivers to feel more confident. There is a need for HCPs to clearly establish what is expected of the FCG on a daily basis. “What part of this care team do you want to play? The family caregiver ought to be given some of that role if they want it and are capable of doing it…we have to engage in the conversation upfront and ask the family caregiver.”(C-1, P) |

| Perform initial and ongoing FCG assessments | The physical and psychosocial status of FCGs should be assessed by trained professionals. Identifying the unique values and needs of each FCG may allow HCPs to offer specific, family-centred support. HCPs need to recognize that the care unit includes the patient who is ill as well as FCGs. “Is it going to be more time-consuming initially – absolutely, because we’re going to have to change the way we work, but down the road if we look at how those assessments are betting integrated, we’ve got carers involved, we start measuring quality of life – we might be in a different place.” (ACN-2, P) |

| Increase HCP understanding of senior-specific conditions and end-of-life care | HCPs lack an understanding of senior-specific conditions and end-of-life care. As such, they are not always able to provide FCGs with sufficient information or supportive resources. “…the family should sit down with someone to describe the disease and how it affects the person you love.” (C-3, G) |

| Advocate for policy change to address coding procedures | Policies should be changed to appropriately compensate HCPs for time spent with FCGs. Providing a code to bill for these interactions may encourage HCPs to engage with FCGs and reduce the tension between task demands and person-centred care. “The payment system for physicians to care about family caregiving, that’s what drives them. We have to take on the legislation of high-end FOIP and figure out how we can record on caregivers, and we also have to address the funding.” (OS-2, R) |

|

| |

| Key Theme 4. Fostering Resilience in Family Caregivers | |

|

| |

| Teach FCGs to self-identify signs of stress and employ stress-management strategies | HCPs can help FCGs self-identify signs of stress by providing information about symptoms and potential risk factors. Training for HCPs should include self-care strategies that can be taught to FCGs. Providing FCGs with coping strategies may prevent further deterioration, enhance well-being, and empower them to overcome challenging situations. “There is sorrow but there is joy. If you get that support, then really you’ve got a journey that’s not all that bad, like it’s hard but it’s not the end, there’s still hope.” (SN-3, Gy) |

| Empower FCGs by identifying their strengths and abilities | Helping FCGs to recognize their personal strengths and abilities may improve their perceived competence and foster feelings of hope. “If I asked a physician what is a strength-based approach on working with patients, I don’t know if they’d be able to articulate what that is.” (SN-2, P) |

| Community resilience hubs | Establishing networks where FCGs can connect for peer support may contribute to improving quality of life and building resilience. “A community resilience hub that is both virtual, like online for those that don’t want to come in, but also an actual meeting place where people can get peer support. There’s a lot of research around peer support, so a lot of brilliant strategies and interventions to help with people’s resilience.” (SN-3, Gy) |

| Prepare future generations for caregiving | HCPs should seek to educate and prepare younger generations for the inevitability that they will become FCGs in the future. Introducing upcoming generations to the caregiver role can increase awareness and empathy in the emerging population of future HCPs and FCGs. “…a need to start with kids, we’ve seen in our culture changes have come just because teachers are starting with kids.” (CC-1, black) |

|

| |

| Key Theme 5. Navigating Health and Social Systems and Accessing Resources | |

|

| |

| Increase HCPs understanding of the health-care system. | If HCPs understand the policies, resources, and services that make up the health-care system, they can better assist FCGs in navigating services and accessing appropriate resources. “I don’t believe every health professional should be expected to know everything about the whole system, but they should have enough wherewithal to know who and how, and who to connect families too appropriately.”(C-2, blue) |

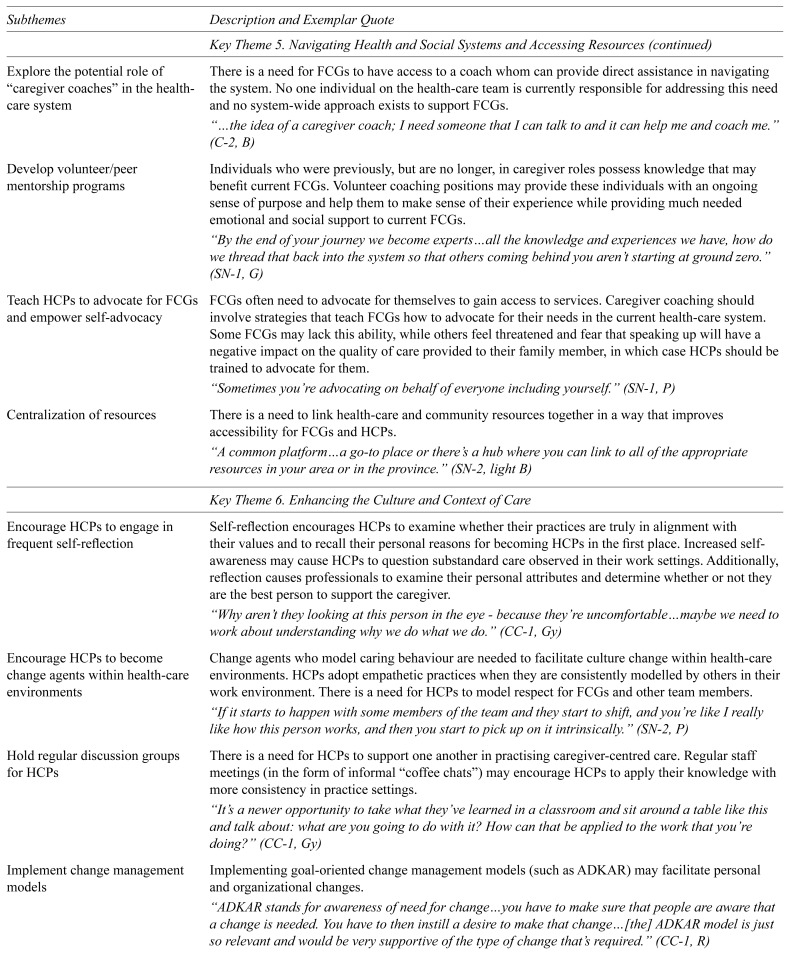

| Explore the potential role of “caregiver coaches” in the health-care system | There is a need for FCGs to have access to a coach whom can provide direct assistance in navigating the system. No one individual on the health-care team is currently responsible for addressing this need and no system-wide approach exists to support FCGs. “…the idea of a caregiver coach; I need someone that I can talk to and it can help me and coach me.” (C-2, B) |

| Develop volunteer/peer mentorship programs | Individuals who were previously, but are no longer, in caregiver roles possess knowledge that may benefit current FCGs. Volunteer coaching positions may provide these individuals with an ongoing sense of purpose and help them to make sense of their experience while providing much needed emotional and social support to current FCGs. “By the end of your journey we become experts…all the knowledge and experiences we have, how do we thread that back into the system so that others coming behind you aren’t starting at ground zero.” (SN-1, G) |

| Teach HCPs to advocate for FCGs and empower self-advocacy | FCGs often need to advocate for themselves to gain access to services. Caregiver coaching should involve strategies that teach FCGs how to advocate for their needs in the current health-care system. Some FCGs may lack this ability, while others feel threatened and fear that speaking up will have a negative impact on the quality of care provided to their family member, in which case HCPs should be trained to advocate for them. “Sometimes you’re advocating on behalf of everyone including yourself.” (SN-1, P) |

| Centralization of resources | There is a need to link health-care and community resources together in a way that improves accessibility for FCGs and HCPs. “A common platform…a go-to place or there’s a hub where you can link to all of the appropriate resources in your area or in the province.” (SN-2, light B) |

|

| |

| Key Theme 6. Enhancing the Culture and Context of Care | |

|

| |

| Encourage HCPs to engage in frequent self-reflection | Self-reflection encourages HCPs to examine whether their practices are truly in alignment with their values and to recall their personal reasons for becoming HCPs in the first place. Increased self-awareness may cause HCPs to question substandard care observed in their work settings. Additionally, reflection causes professionals to examine their personal attributes and determine whether or not they are the best person to support the caregiver. “Why aren’t they looking at this person in the eye - because they’re uncomfortable…maybe we need to work about understanding why we do what we do.” (CC-1, Gy) |

| Encourage HCPs to become change agents within health-care environments | Change agents who model caring behaviour are needed to facilitate culture change within health-care environments. HCPs adopt empathetic practices when they are consistently modelled by others in their work environment. There is a need for HCPs to model respect for FCGs and other team members. “If it starts to happen with some members of the team and they start to shift, and you’re like I really like how this person works, and then you start to pick up on it intrinsically.” (SN-2, P) |

| Hold regular discussion groups for HCPs | There is a need for HCPs to support one another in practising caregiver-centred care. Regular staff meetings (in the form of informal “coffee chats”) may encourage HCPs to apply their knowledge with more consistency in practice settings. “It’s a newer opportunity to take what they’ve learned in a classroom and sit around a table like this and talk about: what are you going to do with it? How can that be applied to the work that you’re doing?” (CC-1, Gy) |

| Implement change management models | Implementing goal-oriented change management models (such as ADKAR) may facilitate personal and organizational changes. “ADKAR stands for awareness of need for change…you have to make sure that people are aware that a change is needed. You have to then instill a desire to make that change…[the] ADKAR model is just so relevant and would be very supportive of the type of change that’s required.” (CC-1, R) |

| Improve communication between HCPs | There is a need for HCPs in different organizations and levels of care to accurately communicate information regarding FCGs. Doing so will reduce caregiver’s frustration and the need to repeatedly share information and advocate for their needs. “Communication [is needed] around how to engage with each other as care providers – which in the end extends to the family.” (CC-1, P) |

| Practice consistent language across health-care settings | Language creates culture. There is a need to eliminate language that invalidates and disrespects FCGs. Establishing guidelines for language may facilitate a culture shift that honours and respects FCGs. “We need to work towards consistent language, and that’s as simple as creating a definition document. We have to change our own language and the way we write, communicate, and speak, so that helps create change elsewhere.” (ACN-3, P) |

| Increase interdependence and multidisciplinary practice | There is a tendency for HCPs to operate in silos. Sharing knowledge and resources between HCPs facilitates more holistic patient care. There is a need to implement an interdisciplinary team approach that extends to community resources when working with FCGs. “I want health-care providers to get over their egos and the system to be less siloed so that people do really think about my needs and where I need to go, and integrated care so I don’t tell my story over and over again, so all my information is in one system that everybody shares – that would be ideal.” (C-2, B) |

Theme 1: Understanding and Recognizing the Caregiver Role

Participants stressed that, while FCGs play a vital role in the care of older adults, their contributions to patient care and the health-care system are often overlooked. This was seen as contributing to the lack of urgency to improve services for FCGs. As HCPs receive little training about FCGs, their understanding is limited regarding both the contributions of FCGs to patient care and the physically and emotionally demanding nature of caregiving.

Participants recommended that HCPs become familiar with caregivers’ contributions, the physical and psychosocial costs of caregiving, and the potential impacts of caregiving on the quality of life of FCGs and care recipients. Awareness of the task demands and emotional needs of caregiving is essential to helping HCPs support FCGs, advocate for policy changes, and improve HWFT.

Theme 2: Communicating with Caregivers

Participants noted that interactions between FCGs and HCPs are not always as supportive as they could be, with FCGs reporting at times feeling disrespected, unheard, and invalidated. Perceived lack of empathy and compassion increases FCGs’ frustration with and distrust of HCPs and the healthcare system. Policies and legislation that limit communication between HCPs and FCGs were also discussed. While HCPs recognized that FCGs value transparent and honest communication, they were hesitant to share information or involve FCGs in treatment planning due to privacy policies and a patient-focus. As a result, HCPs reported feeling uncomfortable interacting with FCGs; some reported making efforts to avoid interacting with them. Further, HCPs felt ill-equipped to offer emotional support and manage difficult family conversations.

Stakeholders emphasized that HWFT ought to better prepare HCPs to listen actively, convey empathy and equality, and offer emotional support.

Theme 3: Partnering with Family Caregivers

Partnering with FCGs can pose a challenge even to well-intentioned HCPs. System demands that prioritize job efficiency over spending time engaging with patients and families can make it difficult for HCPs to take time for FCGs. FCGs also do not frequently self-identify as caregivers, which makes it all the more difficult for HCPs to identify and assess their unique strengths, limitations, and needs. The absence of policies mandating engagement with and providing care to FCGs further impedes support provided to FCGs. Stakeholders noted that HCPs often do not involve FCGs in care planning and, at times, lack knowledge about medical conditions or end-of-life care. FCGs expressed concern with the lack of important information they received regarding their family member’s diagnosis. They often assumed that HCPs themselves lacked important knowledge and experience with certain conditions, causing them to doubt the quality of care their family member was receiving.

Stakeholders recommended that HCPs be mandated and trained to connect with FCGs. Partnering with FCGs was seen as being essential to improving the quality of life of both FCGs and care recipients. Stakeholders acknowledged that involving FCGs may require initial time and effort. Nonetheless, they emphasized that the insights and contribution offered by FCGs would ultimately save time and resources.

Theme 4: Fostering Resilience in Family Caregivers

Participants recognized that providing care can be simultaneously meaningful and extremely challenging. The need for HCPs to work alongside FCGs to increase their ability to cope with adversity and thrive while caregiving was seen as essential. It was generally reported that HCPs lack an understanding, however, of how to empower FCGs and facilitate their resilience. While research on resilience-building strategies exists, its application to FCGs has yet to be translated into practice.

Participants emphasized that HCPs could enhance FCG resilience by using a caregiver-centred approach, inclusive of taking time to better understand FCGs, identifying and building upon their strengths, and making educational and therapeutic resources available. HCPs could also facilitate risk-reduction by teaching FCGs to recognize and manage their physical and psychological stressors. Further, the importance of preparing younger generations for the inevitability of caregiving was identified. Participants emphasized the need to introduce youth to the concept of family caregiving and resilience-building. Establishing resilience hubs that connect health and community services may also provide FCGs with an accessible source of psychological support.

Theme 5: Navigating Health and Social Systems and Accessing Resources

Navigating the health-care system can be challenging, frustrating, and time-consuming for both HCPs and FCGs. Although various health and social services are available, they are often disconnected and under-resourced. FCGs and HCPs can also lack awareness of programs and resources available at different levels of care and within health and community organizations. This can make it difficult for HCPs to offer FCGs appropriate and timely referrals. While some HCPs (e.g., social workers) have system navigator training, others do not, and job demands and competing priorities can limit their availability to facilitate system navigation.

Stakeholders recommended increasing HCPs’ awareness of health and community resources, and equipping them with skills both to coach FCGs to make informed decisions and to advocate for their needs. Participants also emphasized the importance of reducing system fragmentation to improve accessibility for both HCPs and FCGs, and suggested designing specific coach positions to ensure that FCGs receive assistance. Participants also noted that it would be invaluable to engage previous FCGs as coaches. This may serve a dual purpose of providing experienced FCGs with an ongoing sense of meaning while also supporting individuals who are new to the caregiving role.

Theme 6: Enhancing the Culture and Context of Care

Some practices, attitudes, and standards of care that have become entrenched in health-care organizational cultures were described as being ineffective, particularly as they relate to supporting FCGs. The need for HCPs to identify, question, and challenge such practices and norms within health-care settings, as well as their own practices and potential biases, was identified.

Stakeholders suggested that goal-oriented, change management models may facilitate multi-level system change. The consistent use of people-first language across facilities was identified as a potential way to stimulate system-wide change that is acknowledging and respectful of FCGs. Fostering self-reflection, positive workplace behaviour, and interdependence between HCPs and FCGs were envisioned as ways to help facilitate a culture shift towards greater support for FCGs. It was also recommended that HCPs engage in regular staff meetings and group discussions to assess care and support provided at the unit and organizational levels.

DISCUSSION

The Health-care Workforce Training in Supporting Family Caregivers of Seniors in Care symposium aimed to identify HWFT strategies to address HCP learning and practice gaps as it relates to providing caregiver-centred care. Symposium participants highlighted barriers, facilitators, and recommendations to the provision of support for FCGs. Our analysis supports a growing body of literature demonstrating that, while awareness of FCGs is increasing, the limited care provided to FCGs can negatively impact the health of both FCGs and care recipients.(12,13,25) Further, while person-centred care provision is commonplace across Canada, providing care and support to caregivers is less so and frequently overlooked.(26) Participants advocated for a caregiver-centred care approach that focuses on identification, assessment and engagement of FCGs and use of caregiver-centred practice skills.(27)

Provision of caregiver-centred care necessitates that HCPs recognize the unique contributions and needs of FCGs, and actively and respectfully involve them as equal partners in the planning, delivery, and monitoring of patient care.(28) Cultivating caregiver-centred care, however, requires a culture shift at all levels.(29–34) HCPs can encourage one another to consistently create supportive cultures by modelling caregiver-centred care behaviours, engaging in regular discussions around the quality of care being provided to FCGs,(13,29) and making structural changes—however minor—such as adding a chair to accommodate a FCG during meetings.(35)

To support FCGs effectively, HCPs need to be aware of, and attentive to, the impact that caregiving can have on the overall quality of life of FCGs.(11,36) Recognizing such impacts may contribute to a better understanding and appreciation of the role of FCGs.(9,19) Health workforce training that emphasizes the lived experience and contributions of FCGs and consequences of caregiving(11,37) can deepen HCP understandings of FCGs. Such awareness can heighten HCP empathy toward FCGs, and foster compassionate interactions between HCPs and FCGs.(38)

Care outcomes can improve when both patients and FCGs are engaged in care delivery.(35,39,40) Person-centred care recognizes that FCGs and care recipients are experts in their unique situations, and that working together with professionals can lead to better outcomes. When HCPs support families in carrying out their roles, FCGs are better equipped to manage caregiving responsibilities and make informed decisions.(28) A key priority of HWFT programs is, therefore, to prepare HCPs to partner with FCGs. Such partnerships can promote meaningful engagement in care planning, provision, and decision-making.(28) Sharing personal experiences, collaborating with HCPs around care planning, and setting priorities for health-care organizations are not only foundational engagement activities, but also offer opportunities for HCPs to receive timely feedback from—and respond in a timely manner to—FCGs.(35,41)

FCGs want to establish meaningful relationships with HCPs.(42–43) Being consulted about the care of their older adult care partner, invited to participate in care, and provided with regular updates can lead to more positive relationships between FCGs and HCPs.(43) As the level of involvement FCGs desire may differ, it is important for HCPs to discuss FCGs’ expectations and desired levels of engagement.(10,43) Doing so can clarify expectations, and potentially reduce frustration, fear or guilt that might otherwise arise.(40)

Although communication strategies are taught in postsecondary programs, additional training in communication skills is needed.(10,39) Effective communication was identified as a primary learning objective for all HCP training programs, with research consistently demonstrating links between communication and improved patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes.(44–45) Use of respectful language, active listening, and timely communication are important competencies that can facilitate more supportive interactions with FCGs.(20)

FCGs value empathy and compassion when interacting with HCPs, and benefit from frequent validation,(20) ongoing emotional support, and provision of practical coping strategies. This is particularly the case during periods of heightened stress,(46) or when managing difficult family relationships.(47–48) Training HCPs to be empathetic and compassionate, and to help FCGs cope, become resilient,(46) manage conflicts, and navigate relationships can enable them to better support FCGs. Receipt of such support can make it possible for FCGs to continue caregiving, develop positive coping skills, overcome adversity and the negative effects of caregiving, build resilience, experience personal growth, improve self-efficacy, and foster well-being.(49)

FCGs frequently rely on HCPs to help them navigate health-care systems and connect to community resources—activities that are estimated to consume 15–50% of a caregiver’s time.(12,20,40) Finding, negotiating for and maintaining services,(50) as well as navigating the complexities of health and community systems, can be onerous and intimidating.(38,47) While HCP support with navigation can reduce FCG stress, it is important to consider that some FCGs prefer exploring resources and making decisions for themselves.(40,50) Training HCPs in system navigation and determination of FCG needs in this regard can better position HCPs to determine and provide the appropriate level of FCG support.

Privacy and billing policies that impede HCPs from delivering person-centred care and limit FCG engagement across various levels of care can be frustrating for FCGs and HCPs alike.(35) Involving FCGs in policy and program development may provide organizations and HCPs with important perspectives that they might be able to draw upon when informing and advocating for fundamental policy and practice changes.(35) Advocacy for change at the policy and practice levels is essential.

Intentional efforts are required at the individual, organizational, and systems levels to support FCGs and facilitate culture change toward more caregiver-centred care. The input of FCGs, HCPs, academics, researchers, and policy and decision-makers is critical to this endeavour. Symposium participants—offering their personal, caregiving, professional and academic expertise—were cognizant of the ever-increasing and often overlooked importance of drawing on FCGs and their lived experience when determining HCP competencies and curricula, ways to best support FCGs, and priorities around policy, practice, and culture change. Going forward, enhanced engagement with FCGs will be all the more vital to informing and mobilizing caregiver-centred care delivery across the health-care system.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. The one-day, in person format may have limited who was able to attend the symposium. There was a higher proportion of academics and administrators in attendance, and only participants who had participated in previous symposia were invited to attend. These factors may have affected the scope and generalizability of findings, which were intended to reflect themes from front line clinical interactions with FCGs. The majority of academics were also practising HCPs with knowledge of HWFT and practices. In addition, participants were assigned to working groups with discussion topics developed by the research team, which may have shaped the results. The themes were identified from previous symposia which specially sought the views of a range of stakeholders, especially FCGs. The themes and concerns identified are specific to current practices within Alberta, and therefore might not be generalizable to other locations or health-care systems. Time constraints and group dynamics may also have limited the contributions of group members. That being said, the groups were facilitated by trained facilitators who ensured everyone’s viewpoints were aired, and all participants were able to review study findings. Symposium participants were also asked to validate results and provide feedback.

CONCLUSION

The Health-care Workforce Training in Supporting Family Caregivers of Seniors in Care symposium gave participants an opportunity to identify HWFT strategies that might address learning and practice needs of HCPs as they relate to providing caregiver-centred care to FCGs. A review of the literature, survey responses, and working group findings isolated key elements of HWFT curricula including: 1) understanding and recognizing the caregiver role; 2) communicating with FCGs; 3) partnering with FCGs; 4) fostering resilience among caregivers 5) navigating health and social systems and accessing resources; and 6) enhancing the culture and context of care. Study findings will inform the development of and research around a health workforce competency framework and HWFT curriculum specific to training HCPs in best-practices for supporting FCGs and providing caregiver-centred care.

Although initial topics for HWFT were determined, specific learning objectives, content, and means of training delivery require further research. Future studies might involve a larger sample of FCGs and front line HCPs to expand further upon and validate the themes identified by the current study. Incorporating a discussion group with no assigned topic or a topic that is selected by FCGs may also be beneficial for identifying further concerns and themes. Additionally, future focus groups with HCPs and academics may centre around what training methods may be most effective and realistic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was partially funded by a Northern Alberta Academic Family Medicine Fund. Our sincere thanks to the attendees of this symposium for all of their contributions.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Statistics Canada. Age and sex, and type of dwelling data: key results from the 2016 Census. The Daily. 2017. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/170503/dq170503a-eng.pdf.

- 2.Ortman J, Velkoff V, Hogan H. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Available from: https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rising demand for long-term services and supports for elderly people. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office US; 2013. Available from: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/44363-ltc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermus G, Stonebridge C, Thériault l, et al. Home and community care in Canada: an economic footprint. Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Change Foundation. Out of the shadows and into the circle: partnering with family caregivers to shift Ontario’s healthcare system. Toronto, ON: The Foundation; 2015. Available from: https://www.southwesthealthline.ca/healthlibrary_docs/Change-Foundation-strategic-plan.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barello S, Savarese M, Graffigna G. The role of caregivers in the elderly healthcare journey: insights for sustaining elderly patient engagement 1 Caregiver engagement for elderly care: what matters? In: Graffingna G, Barello S, Triberti S, editors. Patient engagement: a consumer-centered model to innovate healthcare. Chap. 9. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter GmbH; 2016. pp. 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fast J. Caregiving for older adults with disabilities: present costs, future challenges. Montreal, QC: Institute for Research on Public Policy; 2015. Available from: http://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/study-no58.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavalko E. Caregiving and the life course: connecting the personal and the public. In: Settersten RA, Angel JL, editors. Handbook of sociology of aging. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 603–18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adelman R, Tmanova L, Delgado D, et al. Caregiver burden a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052–59. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parmar J, Torti J, Brémault-Phillips S, et al. Supporting family caregivers of seniors within acute and continuing care systems. Can Geriatr J. 2018;21(4):292–96. doi: 10.5770/cgj.21.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine C. Supporting family caregivers: the hospital nurse’s assessment of family caregiver needs. Am J Nurs. 2011;111(10):47–51. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000406420.35084.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz R, Beach S, Friedman E, et al. Changing structures and processes to support family caregivers of seriously ill patients. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S36–S42. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Quality Ontario. The reality of caring: distress among caregivers of homecare patients. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guberman N, Lavoie J, Blein L, et al. Baby boom caregivers: care in the age of individualization. Gerontologist. 2012;52(2):210–18. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black B, Johnston D, Rabins P, et al. Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: findings from the maximizing independence at home study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(12):2087–95. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badovinac L, Nicolaysen L, Harvath T. Are we ready for the CARE Act?: Family Caregiving Education for Health Care Providers. J Gerontol Nurs. 2019;45(3):7–11. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20190211-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen M, Agbata I, Canavan M, et al. Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Geritr Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):130–43. doi: 10.1002/gps.4208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulz R, Czaja S. Family caregiving: a vision for the future. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26(3):358–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz R, Eden J, editors. Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charles L, Bremault-Phillips S, Parmar J, et al. Understanding how to support family caregivers of seniors with complex needs. Can Geriatr J. 2017;20(2):75–84. doi: 10.5770/cgj.20.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holroyd-Leduc J, McMillan J, Jette N, et al. Stakeholder Meeting: Integrated knowledge translation approach to address the caregiver support gap. Can J Ageing/Rev Canadienne Du Vieillissement. 2017;36(1):108–19. doi: 10.1017/S0714980816000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmar J. Group Planning Summary, Aug. 30, 2017. Edmonton, AB: Covenant Health; 2017. Fostering resilience in family caregivers of seniors in care. Retrieved from http://seniorsnetworkcovenant.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Final-Report-FCG-Symposium-2017-FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxwell J. A realist approach for qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canadian Institutes of Health Information. Supporting informal caregivers: the heart of home care. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Information; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillick MR. The critical role of caregivers in achieving patient-centered care. JAMA. 2013;310(6):575–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowe JM, Rizzo VM. The contribution of practice skills in a care management process for family caregivers. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2013;56(7):623–39. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2013.817497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolff J, Boyd C. A look at person-centered and family-centered care among older adults: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1497–504. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3359-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heschl C, Arcand A. Measures to better support seniors and their caregivers. Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada; 2019. [Accessed January 20, 2019]. https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/health-advocacy/Measures-to-better-supportseniors-and-their-caregivers-e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearson C, Watson N. Implementing health and social care integration in Scotland: Renegotiating new partnerships in changing cultures of care. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(3):e396–e403. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bokhour B, Fix G, Mueller N, et al. How can healthcare organizations implement patient-centered care? Examining a large-scale cultural transformation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):168. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2949-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dupuis S, McAiney C, Fortune D, et al. Theoretical foundations guiding culture change: the work of the Partnerships in Dementia Care Alliance. Dementia. 2016;15(1):85–105. doi: 10.1177/1471301213518935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeoman G, Furlong P, Seres M, et al. Defining patient centricity with patients for patients and caregivers: a collaborative endeavour. BMJ Innovations. 2017;3(2):76–83. doi: 10.1136/bmjinnov-2016-000157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witteman H, Chipenda Dansokho S, Colquhoun H, et al. Twelve lessons learned for effective research partnerships between patients, caregivers, clinicians, academic researchers, and other stakeholders. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):558–62. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4269-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuluski K, Kokorelias KM, Peckham A, et al. Twelve principles to support caregiver engagement in health care systems and health research. Patient Experience J. 2019;6(1):141–48. doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossman B, Webb C. Family support in late life: a review of the literature on aging, disability, and family caregiving. J Fam Soc Work. 2016;19(4):348–95. doi: 10.1080/10522158.2016.1233924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montgomery RJ, Kosloski KD. Pathways to a caregiver identity and implications for support services. In: Talley RC, Mongomery RJV, editors. Caregiving across the lifespan: research, practice, policy. New York: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith-Carrier T, Pham T, Akhtar S, et al. ‘It’s not just the word care, it’s the meaning of the word... (they) actually care’: Caregivers’ perceptions of home-based primary care in Toronto, Ontario. Age Soc. 2018;38(10):2019–40. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X1700040X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly K, Reinhard SC, Brooks-Danso A. Professional partners supporting family caregivers. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(9 Suppl):6–12. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336400.76635.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palos G, Hare M. Patients, family caregivers, and patient navigators: a partnership approach. Cancer. 2011;117(S15):3590–600. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dionne-Odom J, Azuero A, Lyons K, et al. Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1446–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Creasy KR, Lutz BJ, Young ME, et al. The impact of interactions with providers on stroke caregivers’ needs. Rehabil Nurs. 2013;38(2):88–98. doi: 10.1002/rnj.69. Epub March 25, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graneheim U, Johansson A, Lindgren B. Family caregivers’ experiences of relinquishing the care of a person with dementia to a nursing home: insights from a meta-ethnographic study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28(2):215–24. doi: 10.1111/scs.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bachmann C, Abramovitch H, Barbu C, et al. A European consensus on learning objectives for a core communication curriculum in health care professions. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(1):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denniston C, Molloy E, Nestel D, et al. Learning outcomes for communication skills across the health professions: a systematic literature review and qualitative synthesis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4):e014570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dias R, Santos R, de Sousa M, et al. Resilience of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review of biological and psychosocial determinants. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2015;37(1):12–19. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2014-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ablitt A, Jones GV, Muers J. Living with dementia: a systematic review of the influence of relationship factors. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(4):497–511. doi: 10.1080/13607860902774436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pine J, Steffen A. Intergenerational ambivalence and dyadic strain: understanding stress in family care partners of older adults. Clin Gerontol. 2019;42(1):90–100. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1356894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joling KJ, Smit F, Van Marwijk HWJ, et al. Identifying target groups for the prevention of depression among caregivers of dementia patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(2):298–306. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor M, Quesnel-Vallée A. The structural burden of caregiving: shared challenges in the United States and Canada. Gerontologist. 2017;57(1):19–25. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]