Abstract

Introduction:

Youth with callous-unemotional (CU) traits show severe and chronic forms of antisocial behavior, as well as deficits in socioaffiliative processes, such as empathy, guilt, and prosocial behavior. Adolescence represents a critical developmental window when these socioaffiliative processes can help to deepen the strength of supportive peer friendships. However, few studies have explored the relationship between CU traits and friendship quality during adolescence. In the current study, we used data from the Pathways to Desistance dataset to examine reciprocal and longitudinal associations between CU traits and friendship quality at three assessment points separated by 6 months each during adolescence.

Methods:

The sample included adolescents who had interacted with the justice system (age at baseline, M=16.04, SD=1.14; N=1354; 13.6% female). CU traits were assessed using the callousness scale of the self-reported Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory and friendship quality using a scale adapted from the Quality of Relationships Inventory. Models accounted for co-occurring aggression, impulsive-irresponsible traits, grandiose-manipulative traits, age, gender, location, and race.

Results:

At every assessment point, CU traits were uniquely related to lower friendship quality. Moreover, we found evidence for reciprocal effects between the first two assessment points, such that CU traits were related to decreases in friendship quality over time, while lower friendship quality simultaneously predicted increases in CU traits across the same period.

Conclusions:

Interventions for CU traits could benefit from including specific modules that target the social processes associated with adaptive and successful friendships, including empathic listening and other-orientated thinking.

Keywords: affiliation, antisocial behavior, callous-unemotional traits, friendship, psychopathology

A large body of research has established the importance of adolescent friendships for the development of successful adult relationships and socialization (Buhrmester, 1990; Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Crosnoe, 2000; Crosnoe & Needham, 2004; De Wied, Branje, & Meeus, 2007). During adolescence, the amount of time that children spend outside the home and among peers dramatically increases, with peer friendships becoming increasingly influential on social interactions and behavior (Buhrmester, 1990; Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Hartup, 1996). In particular, friendships provide a framework for adolescents to learn and refine socioemotional skills that support the development of positive relationships in adulthood (Crosnoe, 2000; Crosnoe & Needham, 2004). Through interactions with friends and peers, adolescents are able to cement their cooperation skills and hone their ability to understand the perspectives of others (Meeus, 2016). High levels of friendship quality and supportive friendships are typically indexed by concern, liking, loyalty, and mutual obligation between friends (Barry & Wentzel, 2006; Vitaro, Boivin, & Bukowski, 2009). More broadly, friendship quality is evidenced by strong social connections with friends (e.g., counting on friends to provide support and help) and companionship (e.g., shared activities) (Padilla-Walker, Fraser, Black, & Bean, 2015).

Several interpersonal and affiliative processes contribute to the development and maintenance of healthy, positive, and high-quality adolescent friendships, (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Chow, Ruhl, & Buhrmester, 2013; De Wied et al., 2007). First, empathy (i.e., sharing in the perspectives and feelings of others) is thought to play a critical role in the development of quality adolescent friendship by promoting prosocial responding (De Wied et al., 2007). For example, in response to intimate or emotionally sensitive information, an empathic response from a peer can help validate the disclosing friend’s experiences, build trust, and deepen the friendship. More specifically, the ability to enact a sensitive and caring response to a peer relies on sensitively recognizing and resonating with the emotions of that person, a core component of empathy (Spinrad et al., 2006). Second, guilt represents the aversive moral emotion that accompanies knowledge that one has committed a misdeed that could harm a relationship or friendship (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994). Within this scenario, the onset of guilt prompts an individual to apologize, enact reparation behaviors, and seek to resolve the conflict (De Wied et al., 2007; Roberts, Strayer, & Denham, 2014). Thus, empathy, guilt, and conflict resolution represent three highly interrelated mechanisms to promote emotional support and the development and maintenance of high-quality friendships.

At the same time, having high quality friendships could serve to promote prosocial, caring, and empathic behaviors because adolescents are motivated to maintain or improve their social relationships. Having a close network of friends provides opportunities for enacting prosocial behaviors with adolescents repeatedly required to take the perspectives of others, cooperate, and develop other-orientated responsiveness to promote socioemotional connections and companionship (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015). Moreover, close connections with friends might help to increase prosocial and caring behaviors because adolescents learn or mimic such skills from friends who model these types of positive social behaviors or who positively reinforce, validate, or expect such behavior (Wentzel, Barry, & Caldwell, 2004). Accordingly, an absence of high quality friendships may be detrimental to the development and stability of prosocial and caring behaviors across adolescence.

The presence of callous-unemotional (CU) traits in youth is characterized by striking deficits in empathy, guilt, and prosocial behaviors (Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, 2014; Waller et al., 2019a), as well as impairments in socioaffiliative processes, such as physical and verbal affection (Waller et al., 2016) and eye-contact (Dadds et al., 2012). CU traits are also related to severe and chronic forms of antisocial behavior and psychopathic traits (Frick et al., 2014), including interpersonally harmful forms of antisocial behavior, such as proactive aggression (Kimonis et al., 2008) and bullying (Muñoz, 2008). Surprisingly, however, few studies have examined the relationship between friendship quality and CU traits during adolescence, which could provide further insight into the social factors that could contribute to the development and maintenance of CU traits or that could inform novel social intervention targets to help reduce risk for CU traits and antisocial behavior across adolescence (Hyde, Waller, & Burt, 2014).

A handful of studies exist that begun to explore links between CU traits and friendship quality during adolescence. For example some studies have reported associations between the broader psychopathic traits phenotype and difficulties in peer relationships (Muñoz, Kerr, & Besic, 2008), as well as lower quality romantic relationships and friendships (Backman, Laajasalo, Jokela, & Aronen, 2018). However, these findings do not necessarily speak to deficits in friendship quality that could arise specifically in relation to CU traits, as opposed to broader features of psychopathy, such as impulsivity, manipulativeness, or thrill-seeking. In studies conducted in children that have isolated the relation of CU traits and friendship quality by controlling for attention-deficit behaviors or conduct problems, CU traits have been linked to peer rejection and dislike (Piatigorsky & Hinshaw, 2004) and greater experience of physical and verbal peer victimization (Fontaine, Hanscombe, Berg, McCrory, & Viding, 2018). Moreover, CU traits were linked to more peer rejection particularly when children had co-occurring conduct problems and poor impulse control (Andrade, Sorge, Djordjevic, & Naber, 2015; Waller, Hyde, Baskin-Sommers, & Olson, 2017). These studies suggest that CU traits make it harder for children and adolescents to develop quality friendships in the first place because these youth find themselves quickly rejected by peers.

At the same time, in a sample of children aged 8–13 years old, Haas and colleagues also found that CU traits were related to children reporting less intimate exchange and less satisfaction within friendships (Haas, Becker, Epstein, & Frick, 2018). In addition, in a sample of school-aged children, those with high and stable CU traits across three annual follow-ups beginning at age 9 reported experiencing lower support from peers relative to children with low CU traits across the same period (Fanti, Colins, Andershed, & Sikki, 2017). Finally, in a sample of 8–11 year old children with social, emotional, and behavioral difficulties, Warren, Jones and Frederickson (2015) found that despite children with high CU traits being more socially rejected and rated more negatively by peers than children with low levels of CU traits, the social self-concept of these children was not negatively impacted. Together these studies suggest that children high on CU traits may partly fail to develop adaptive and positive friendships because of peer rejection and reduced motivation for seeking out friendships, as well as less enjoyment from maintaining social closeness with others (Waller & Wagner, 2019).

However, no studies have explored longitudinal relationships between CU traits and individual differences in friendship quality across adolescence, a developmental period characterized by growing independence from parents and more time spent with friends developing peer relationships (Hartup, 1996). Further, while plausible that children high on CU traits are at risk for poorer friendship quality over time, it is also possible that experiencing poorer friendship quality could contribute to chronicity in CU traits over time. Within this framework, and as outlined above, an absence of supportive friendships could mean that adolescents have fewer opportunities to enact empathic, prosocial, and caring behaviors within the context of social relationships (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015), further increasing the risk of peer rejection and poor friendship quality, ultimately compounding risk for CU traits in a bidirectional cascade. To explore this potential reciprocity in links between CU traits and poor friendship quality during adolescence, prospective longitudinal studies that examine bidirectional associations between CU traits and poor friendship quality over time are needed.

Current Study

The current study addressed these questions by examining the relationship between CU traits and friendship quality during adolescence. In particular, we examined both cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships between CU traits and friendship quality and tested longitudinal and reciprocal links between CU traits and friendship quality across three assessment periods. We operationalized friendship quality using a measure that assessed both companionship and social connection within friendships. We hypothesized that CU traits would be associated with lower friendship quality across all time-points. Importantly, we hypothesized that these relationships would be specific to CU traits rather than aggression more broadly or other related dimensions of psychopathic traits, including grandiose-manipulative and impulsive-irresponsible traits. Second, we examined longitudinal relationships between CU traits and friendship quality. We hypothesized that there would be reciprocal relationships across time such that higher CU traits would be related to decreases in friendship quality over time, while lower friendship quality would simultaneously be related to increases in CU traits over time.

Methods

Participants

We used data from the Pathways to Desistance project, a multisite, longitudinal study of 1354 juvenile offenders (Schubert et al., 2004). Participants in the current study were youths charged with a serious offense at a court appearance in Philadelphia, PA (N=700) or Phoenix, AZ (N=654). Eligibility for baseline participation included being aged 14–18 years and recently charged with a felony or serious non-felony offense (e.g., misdemeanor weapons offense or sexual assault). A large proportion of offenses for participants were drug-related, thus the proportion with a drug-related offense was capped at 15% to ensure sample heterogeneity in terms of offending. Sixty seven percent of eligible youth who could be located agreed to enroll in the study.

Ethical Considerations

Recruitment and assessment procedures were approved by the IRBs of participating universities. Juveniles were located based on age and adjudicated charge according to names provided by the courts. Once consent was obtained, interviews were arranged in the facility if the juvenile was confined, the juvenile’s home, or an alternative agreed-upon location.

Procedure

Baseline interviews were conducted an average of 36.9 days (SD=20.6) after court appearances and administered over 2 days in two separate 2-hour sessions. Interviewers and participants sat side-by-side facing a computer, and questions were read aloud to avoid problems caused by reading difficulties, with answers also being given aloud. For sensitive questions, a portable keypad was provided to ensure confidentiality of answers. Adolescents were informed of the requirement for confidentiality set by the U.S. Department of Justice that prohibits disclosure of information to anyone outside the research staff, except in cases of suspected child abuse. Adolescents were paid $50 for participating. Participants completed follow-up interviews at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 48, 60, 72 and 84 months past baseline. The current study focused specifically on the relationship between CU traits and friendship quality in adolescence and included data from only the first three follow-up interviews to retain an adolescent population (i.e., at later assessment waves, the average age was >18, with more participants transitioning into emerging adulthood). In the current study, “Time 1”, “Time 2”, and “Time 3” refer to the interviews that took place 6 months, 12 months, and 18 months post-baseline, respectively. Note that a measure of CU traits was only available beginning at the 6-month assessment (not at baseline).

Measures

Friendship Quality.

Friendship quality was assessed by asking participants about their five closest reported friends using the Friendship Quality Scale, a ten-item questionnaire adapted from the Quality of Relationships Inventory designed to assess the depth of adolescent friendships (Pierce, Sarason, Sarason, Solky-Butzel, & Nagle, 1997). The items in this scale specifically focused on supportive qualities of friendship including companionship and connection (e.g. “How much can you count on your friend for help with a problem,” “How much can you count on your friend if a family member died”, and “How much would you miss your friend if you could not see or talk with him/her for a month”) (Supplemental Table 1). Two items focused on negative friendship influences and peer pressure (e.g. “How much has your friend tried to influence you to do something wrong”) were reverse scored. Responses were coded on a 4-point Likert scale from “not at all” to “very much”. The friendship quality scale had good internal consistency at all three time-points (range, α=.80-.82).

Callous-Unemotional Traits.

CU traits were assessed at all three time-points using the CU traits subscale of the Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory (YPI; Andershed, Gustafson, Kerr, & Stattin, 2002), a 50-item self-report measure of psychopathy that forms three dimensions: grandiose-manipulative (e.g. dishonest charm, grandiosity, lying, manipulation), impulsive-irresponsible (e.g. impulsiveness, irresponsibility, thrill-seeking), and CU traits (e.g. remorselessness, callousness, unemotionality). Note that we included the impulsive-irresponsible and grandiose-manipulative dimensions in analyses to ensure specificity of any effects of CU traits. Internal consistencies of each scale were high across the three time points: (CU traits: range, α=.73-.76; Grandiose-Manipulative: range, α=.91-.92; Impulsive-Irresponsible: range, α=.82–85). Important, there was minimal overlap in item content between the measure of CU traits and friendship quality (see Supplemental Table 1).

Aggression.

We assessed aggression at all three time-points using the suppression of aggression subscale (e.g., “people who get me angry better watch out”) of the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory (WAI; Weinberger & Schwartz, 1990), a widely-used assessment of an individual’s social-emotional adjustment within the context of external constraints. The measure asks participants to rank how much (1= false to 5= true) their behavior in the past six months matches a series of statements. Higher scores indicate more positive behavior (i.e., better suppression of aggression). The suppression of aggression subscale showed good internal consistency across all three time points (time 1, α=.79, time 2, α=.78; time 3, α=.82). This construct was included to establish specificity of any effects of CU traits on friendship quality, over and above the influence of broader aggression (Bagwell & Coie, 2004), and indeed, lower scores on the suppression of aggression measure were correlated with worse friendship quality (see Supplemental Table 2).

Covariates.

We included other covariates that could influence relationships between friendship quality and predictor variables. (1) Gender: 13.5% of participants were female. (2) Race: 42% of participants were African-American, 34% Hispanic-American, 20% Caucasian, 3% biracial, and 2% Native-American; models included a single recoded race variable (non-Caucasian=0, Caucasian=1). (3) Age. Age at baseline (M=16.04, SD=1.14). (4) Location. To account for the fact that interviews with participants varied in location, with some carried out in participants’ homes and others in a detention center or other locked facility, which could impact the ability to form meaningful interpersonal connections and friendships with peers, we created a binary location variable, which we accounted for in relevant models (0=at home/somewhere else in the community vs. 1=in a detention center, jail, or other locked facility). The proportion of the sample in a detention center, jail, or other locked facility each assessment wave was as follows: time 1=50%, time 2=37%, time 3=32%).

Analytic Strategy

All models were tested in Mplus version 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015). While the amount of missing data was low (covariance coverage =.71-.96), we used full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to accommodate any missing data and provide less biased estimates than likewise or pairwise deletion (Enders, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002). First, within multivariate regression analyses, we explored the associations between CU traits and friendship quality in adolescence at each time point, controlling for gender, age, race, location of interview, grandiose-manipulative traits, impulsive-irresponsible traits, and aggression. Second, to examine the bidirectional relationship between CU traits and friendship over time, we explored a longitudinal, cross-lagged panel model with gender, race, and age included as covariates.

Results

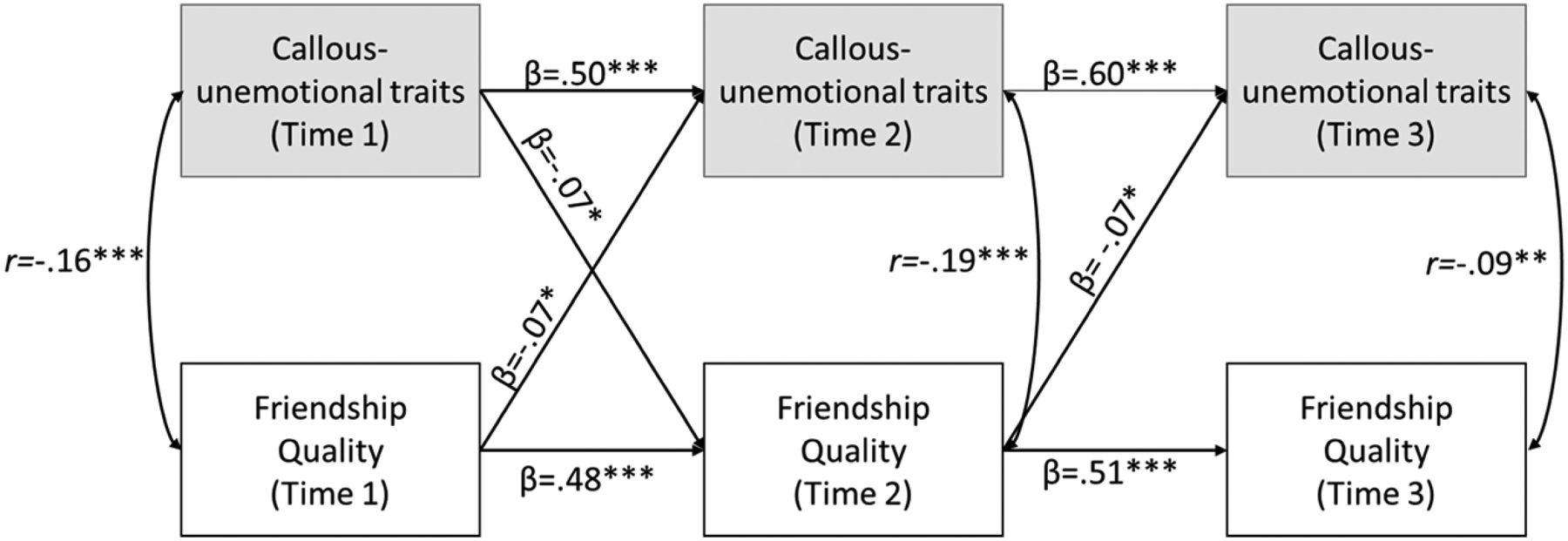

Descriptive statistics between all study variables are presented in Table 1 and bivariate correlations in Supplemental Table 2. Within all three cross-sectional regression models, we found that CU traits were significantly related to lower friendship quality at Time 1 (β =−.11, p<.01), Time 2 (β=−.25, p<.01), and Time 3 (β =−.11, p<.01; Table 2), controlling for gender, age, race, grandiose-manipulative and impulsive-irresponsible traits, location, and aggression at each time point. Within the longitudinal model, and beyond stability in friendship quality and CU traits (range, β=.48-.60, p<.001), we found evidence for reciprocal effects. Specifically, lower friendship quality at Time 1 predicted higher CU traits at Time 2 (β=−.07, p<.05), while simultaneously, higher CU traits at Time 1 predicted lower friendship quality at Time 2 (β =−.07, p<.05). Lower friendship quality at Time 2 also predicted higher CU traits at Time 3 (β =−.07, p< .05), although higher CU traits at Time 2 were unrelated to lower friendship quality at time 3. (Figure 1; Supplemental Table 3). The pattern of findings was largely unchanged with the addition of covariates (Supplemental Table 4).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of main study variables

| N | Min | Max | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friendship Quality Tl | 1180 | 1.30 | 4.00 | 3.35 | 0.49 |

| Friendship Quality T2 | 1195 | 1.30 | 4.00 | 3.33 | 0.50 |

| Friendship Quality T3 | 1142 | 1.30 | 4.00 | 3.33 | 0.51 |

| CU traits Tl | 1079 | 7.00 | 58.00 | 33.33 | 6.91 |

| CU traits T2 | 1260 | 15.00 | 55.00 | 32.49 | 6.70 |

| CU traits T3 | 1227 | 13.00 | 59.00 | 32.09 | 6.88 |

| Grandiose-Manipulative traits Tl | 1079 | 12.00 | 80.00 | 40.19 | 11.78 |

| Grandiose-Manipulative traits T2 | 1260 | 19.00 | 80.00 | 38.91 | 11.38 |

| Grandiose-Manipulative traits T3 | 1227 | 11.00 | 80.00 | 38.25 | 11.65 |

| Impulsive-Irresponsible traits T1 | 1079 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 35.60 | 8.29 |

| Impulsive-Irresponsible traits T2 | 1260 | 15.00 | 60.00 | 34.73 | 8.37 |

| Impulsive-Irresponsible traits T3 | 1227 | 15.00 | 59.00 | 33.91 | 8.70 |

| Suppression of Aggression Tl | 1261 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.82 | .96 |

| Suppression of Aggression T2 | 1260 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.91 | .94 |

| Suppression of Aggression T3 | 1228 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.95 | .98 |

Note. Higher scores for friendship quality variables indicate high quality.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional multivariate regression analyses showed that lower friendship quality was uniquely associated with higher levels of CU traits at each time point during adolescence.

| Outcome variable: Friendship Quality -Time 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors - Time 1 | B | SE | β | P |

| CU traits | −.01 | .003 | −.10 | .01 |

| Grandiose-Manipulative traits | −.001 | .002 | −.03 | .46 |

| Impulsive-Irresponsible traits | −.001 | .003 | −.02 | .64 |

| Aggression | −.004 | .02 | −.01 | .83 |

| Gender | −.21 | .04 | −.15 | <.001 |

| Age | .004 | .01 | .01 | .73 |

| Race | −.13 | .04 | −.11 | <001 |

| Interview location | .06 | .03 | .06 | .05 |

| Outcome variable: Friendship Quality -Time 2 | ||||

| Predictors - Time 2 | B | SE | β | P |

| CU traits | −.02 | .003 | −.24 | <001 |

| Grandiose-Manipulative traits | .001 | .002 | .01 | .91 |

| Impulsive-Irresponsible traits | .003 | .002 | .05 | .21 |

| Aggression | .01 | .02 | .02 | .62 |

| Gender | −.19 | .04 | −.13 | <001 |

| Age | .004 | .01 | .01 | .75 |

| Race | −.12 | .04 | −.10 | .001 |

| Interview location | .07 | .03 | .07 | .02 |

| Outcome variable: Friendship Quality - Time 3 | ||||

| Predictors - Time 3 | B | SE | β | P |

| CU traits | −.01 | .003 | −.10 | .01 |

| Grandiose-Manipulative traits | −.001 | .002 | −.01 | .79 |

| Impulsive-Irresponsible traits | −.002 | .003 | −.04 | .38 |

| Aggression | .02 | .02 | .03 | .35 |

| Gender | −.17 | .04 | −.11 | <.001 |

| Age | .002 | .01 | .004 | .90 |

| Race | −.09 | .04 | −.07 | .01 |

| Interview location | .02 | .03 | .02 | .61 |

Note. We also modeled covariances between all predictor variables in the models (results available on request).

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged model examining bidirectional relationship between friendship quality and CU traits over time Note. ***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05. Figure shows only significant pathways, including correlation coefficients for within-time associations (r) and standardized beta coefficients for longitudinal regression pathways (β). Estimates for all pathways modeled are presented in Supplemental Table 2. The pattern of results was similar including pathways from impulsive-irresponsible traits, grandiose-manipulative traits, aggression, gender, age, and race on all variables in the model (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

We provide consistent evidence that higher levels of CU traits are uniquely related to poorer friendship quality at three different assessments points in adolescence separated by 6 months each. Moreover, the relationship between CU traits and lower friendship quality remained significant after accounting for grandiose-manipulative and impulsive-irresponsible traits, aggression, setting, and other demographic factors, suggesting that something specific about the characteristic features of CU traits, as opposed to psychopathic traits or aggression more broadly, impairs the development of healthy friendships and social affiliation with others. In particular, our results speak to the importance of empathy, prosociality, guilt, and cooperation, essential socioemotional skills that are impaired among youth with CU traits, to the maintenance of high-quality friendships. We also found preliminary evidence for a bidirectional relationship between CU traits and friendship quality over time, but only for the first two assessment points. In particular, across the first two assessment points, poorer friendship quality predicted increases in CU traits over time while CU traits simultaneously predicted decreases in friendship quality. However, while lower friendship quality was related to increases in CU traits across the final two waves, CU traits were not associated with decreases in friendship across this time.

Extant research supports the notion that healthy friendships are indexed by high levels of companionship, connection, and prosocial behavior (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015). Moreover, friendships provide youth with multiple opportunities to be sensitive to their friends’ needs, develop social intimacy, enact supportive behaviors, and even recognize or apologize for hurting a friend’s feelings (De Wied et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2014). Our results suggest that experiencing these healthy friendship processes could help to reduce levels of CU traits. At the same time, at least for the first two assessment waves, higher levels of CU traits also predicted significant decreases in friendship quality over time. Thus, while supportive friendships could help to foster empathic and prosocial skills, such positive friendship qualities could be predicated on children being able to form and maintain friendships in the first place; a feat that may be challenging for children with CU traits who often experience heightened levels of peer rejection (Andrade et al., 2015; Waller et al., 2017), report more conflict in their relationships (Muñoz et al., 2008), and fall prey to more physical and verbal victimization (Fontaine et al., 2018).

One explanation for our findings centers on the deficits in socioaffiliative processes that are thought to underpin CU traits (Viding & McCrory, 2019; Waller & Hyde, 2018; Waller & Wagner, 2019). In particular, preliminary research supports the notion that children high on CU traits show disrupted socioaffiliative processes that could impair the development of adaptive friendships, including reduced motivation for seeking out or enjoyment from maintaining social closeness with others (Waller & Wagner, 2019). For example, CU traits in childhood have been linked to lower parent-directed verbal and physical affection (Waller et al., 2016), lower observed social affiliation (Waller, Wagner, Flom, Ganiban, & Saudino, 2019b), reduced eye-contact with caregivers (Dadds et al., 2012), and less neural sensitivity to the laughter of others and desire to join in with others’ laughter, thought to be indicative of impaired propensity for social connectedness (O’Nions et al., 2017). Evidence also suggests that adolescents with CU traits tend to be highly reward-driven but view social status and dominance as more rewarding than cultivating prosocial or affiliative peer bonds (Pardini & Byrd, 2012). Accordingly, interventions that help adolescents with CU traits to develop supportive friendships might be a novel way of helping to reduce the stability and chronicity of CU traits, especially since high quality friendships have been linked to increases in prosocial behavior over time (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015), and given that higher quality friendship consistently predicted CU traits in our bidirectional model (but not vice versa). Along these lines, a systematic review of youth-focused treatments for CU traits concluded that social skills-focused interventions could be valuable for reducing CU traits (Wilkinson, Waller, & Viding, 2016). Taken in conjunction with our findings, these studies suggest that interventions focused on boosting the socioaffiliative skills necessary for building positive and high-quality friendships might be beneficial for reducing CU traits (Hyde et al., 2014; Waller & Wagner, 2019).

There were a number of strengths to the current study, including the use of a large, longitudinal high-risk sample and testing of multivariate reciprocal effects models to isolate unique associations between CU traits and lower friendship quality. Nevertheless, our findings should be considered alongside several limitations. First, we relied on self-report for all measures. Although youth may be the best reporters of temperament or behavioral features relevant to the current study (Gartstein, Bridgett, & Low, 2012), some studies have reported that adolescents with psychopathic traits exhibit somewhat biased perspectives on their interactions with close peers, including overestimating the pervasiveness of conflict in their interactions (Muñoz et al., 2008). Related, the main effects of CU traits notwithstanding, we found that youth who were in a detention center or other locked facility reported higher friendship quality at time 2 (with a trend-level association at time 1). One on hand, it may be that these settings provide an opportunity for youth to develop close friendships, which may be important when targeting socioaffiliative skills within interventions to reduce CU traits. One the other hand, our results do not rule out the possibility that friendship quality in these settings reflects deviancy training processes or antisocial influences on youth (Reid, 2017). Future studies in other samples examining prospective links between CU traits and friendship quality or social and affiliative interactions with others could include observations and peer-ratings to avoid limitations associated with self- report data collection, as well as observational measures that can explore the potential that friendship quality emerges in the context of negative peer influences. Second, although we controlled for the ability to suppress aggression and other dimensions of psychopathic traits in our analyses, we utilized a high-risk sample of adjudicated offenders and thus our findings may not generalize to community samples. Further, as the current sample was composed of only 13.5% female participants, future studies with larger numbers of female participants are needed to better disentangle whether associations between CU traits and friendship differ between males and females, including through moderation analysis. Finally, these data were drawn from a longitudinal study that included a baseline assessment not incorporated in our models. Specifically, there was no assessment of CU traits at the baseline assessment, motivating our decision to make the 6-month follow-up assessment point our “Time 1” assessment. Thus, we do not know whether inclusion of CU traits at baseline when youth entered the study would impact the findings. Note, however, that friendship quality was assessed at baseline and inclusion of this variable in models did not alter the pattern of findings we report (results available on request).

In sum, our findings highlight the importance of studying friendships as they relate to CU traits. Effective and adaptive friendships are contingent on socioaffiliative skills, including empathy, guilt, and conflict resolution (Buhrmester, 1990; De Wied et al., 2007), processes that appear to be impaired in adolescents with higher CU traits (Waller et al., 2019a). However, our findings demonstrate that while adolescents high on CU traits may struggle to develop positive and high-quality friendships, those who do may be significantly less likely to show persistent and high levels of CU traits across time. Thus, future intervention and treatment efforts involving youth with CU traits could provide the opportunity for adolescents to participate in supportive friendship activities, where they improve their ability to prioritize the feelings of others, harness empathic listening skills, and practice conflict resolution (Waller & Wagner, 2019; Wilkinson et al., 2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

The Pathways Project was supported by funding from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2007-MU-FX-0002), National Institute of Justice (2008-IJ-CX-0023), John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, William T. Grant Foundation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, William Penn Foundation, Center for Disease Control, National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA019697), Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency, and the Arizona Governor’s Justice Commission. C.D.M. was supported by A Louis H Castor, M.D., C’48 Undergraduate Research Grant from the Center for Undergraduate Research & Fellowships at the University of Pennsylvania. R.W. was supported by Institutional Funding from the University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Carly D. Miron, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA.

Emma Satlof-Bedrick, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA.

Rebecca Waller, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA.

References

- Andershed H, Gustafson SB, Kerr M, & Stattin H (2002). The usefulness of self-reported psychopathy-like traits in the study of antisocial behaviour among non-referred adolescents. European Journal of Personality, 16(5), 383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade BF, Sorge GB, Djordjevic D, & Naber AR (2015). Callous–unemotional traits influence the severity of peer problems in children with impulsive/overactive and oppositional/defiant behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(8), 2183–2190. [Google Scholar]

- Backman H, Laajasalo T, Jokela M, & Aronen ET (2018). Interpersonal relationships as protective and risk factors for psychopathy: a follow-up study in adolescent offenders. Journal of youth and adolescence, 47(5), 1022–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, & Coie JD (2004). The best friendships of aggressive boys: Relationship quality, conflict management, and rule-breaking behavior. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88(1), 5–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CM, & Wentzel KR (2006). Friend influence on prosocial behavior: The role of motivational factors and friendship characteristics. Developmental Psychology, 42(1), 153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Stillwell AM, & Heatherton TF (1994). Guilt: an interpersonal approach. Psychological bulletin, 115(2), 243–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D (1990). Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child development, 61(4), 1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, & Furman W (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child development, 1101–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow CM, Ruhl H, & Buhrmester D (2013). The mediating role of interpersonal competence between adolescents’ empathy and friendship quality: A dyadic approach. Journal of adolescence, 36(1), 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2000). Friendships in childhood and adolescence: The life course and new directions. Social psychology quarterly, 63, 377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, & Needham B (2004). Holism, contextual variability, and the study of friendships in adolescent development. Child development, 75(1), 264–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Allen JL, Oliver BR, Faulkner N, Legge K, Moul C, … Scott S (2012). Love, eye contact and the developmental origins of empathy v. psychopathy. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200, 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wied M, Branje SJ, & Meeus WH (2007). Empathy and conflict resolution in friendship relations among adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 33(1), 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2001). A primer on maximum likelihood algorithms available for use with missing data. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(1), 128–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fanti KA, Colins OF, Andershed H, & Sikki M (2017). Stability and change in callous-unemotional traits: Longitudinal associations with potential individual and contextual risk and protective factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(1), 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine NM, Hanscombe KB, Berg MT, McCrory EJ, & Viding E (2018). Trajectories of callous-unemotional traits in childhood predict different forms of peer victimization in adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(3), 458–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, & Kahn RE (2014). Annual Research Review: A developmental psychopathology approach to understanding callous-unemotional traits in children and adolescents with serious conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(6), 532–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Bridgett DJ, & Low CM (2012). Asking questions about temperament: Self-and other-report measures across the lifespan (Zentner M & RL S Eds.): The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haas SM, Becker SP, Epstein JN, & Frick PJ (2018). Callous-unemotional traits are uniquely associated with poorer peer functioning in school-aged children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(4), 781–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW (1996). The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child development, 67(1), 1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Waller R, & Burt SA (2014). Commentary: Improving treatment for youth with callous-unemotional traits through the intersection of basic and applied science–reflections on Dadds et al. (2014). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(7), 781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeus W (2016). Adolescent psychosocial development: A review of longitudinal models and research. Developmental Psychology, 52(12), 1969–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz LC, Kerr M, & Besic N (2008). The peer relationships of youths with psychopathic personality traits: A matter of perspective. Criminal justice and behavior, 35(2), 212–227. [Google Scholar]

- O’Nions E, Lima CF, Scott SK, Roberts R, McCrory EJ, & Viding E (2017). Reduced laughter contagion in boys at risk for psychopathy. Current Biology, 27(19), 3049–3055. e3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Fraser AM, Black BB, & Bean RA (2015). Associations Between Friendship, Sympathy, and Prosocial Behavior Toward Friends. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25(1), 28–35. doi: 10.1111/jora.12108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, & Byrd AL (2012). Perceptions of aggressive conflicts and others’ distress in children with callous-unemotional traits: “I’ll show you who’s boss, even if you suffer and I get in trouble”. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(3), 283–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatigorsky A, & Hinshaw SP (2004). Psychopathic traits in boys with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: concurrent and longitudinal correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(5), 535–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce GR, Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Solky-Butzel JA, & Nagle LC (1997). Assessing the quality of personal relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 14(3), 339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Reid SE (2017). The (anti) social network: Egocentric friendship networks of incarcerated youth. Deviant behavior, 38(2), 154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W, Strayer J, & Denham S (2014). Empathy, anger, guilt: Emotions and prosocial behaviour. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 46(4), 465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, & Graham JW (2002). Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological methods, 7(2), 147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert CA, Mulvey EP, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Losoya SH, Hecker T, … Knight GP (2004). Operational lessons from the pathways to desistance project. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 2(3), 237–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Fabes RA, Valiente C, Shepard SA, … Guthrie IK (2006). Relation of emotion-related regulation to children’s social competence: A longitudinal study. Emotion, 6(3), 498–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, & McCrory E (2019). Towards understanding atypical social affiliation in psychopathy. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(5), 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Boivin M, & Bukowski WM (2009). The role of friendship in child and adolescent psychosocial development In Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. (pp. 568–585). New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, & Hyde LW (2018). Callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood: the development of empathy and prosociality gone awry. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Hyde LW, Baskin-Sommers AR, & Olson SL (2017). Interactions between callous unemotional behaviors and executive function in early childhood predict later aggression and lower peer-liking in late-childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 597–609. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0184-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Trentacosta C, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban J, Reiss D, … Hyde LW (2016). Heritable temperament pathways to early callous-unemotional behavior. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209, 475–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, & Wagner NJ (2019). The Sensitivity to Threat and Affiliative Reward (STAR) Model and the Development of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 656–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Wagner NJ, Barstead MG, Subar A, Petersen JL, Hyde JS, & Hyde LW (2019a). A meta-analysis of the associations between callous-unemotional traits and empathy, prosociality, and guilt. Clinical Psychology Review, 101809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Wagner NJ, Flom M, Ganiban J, & Saudino KJ (2019b). Fearlessness and low social affiliation as unique developmental precursors of callous-unemotional behaviors in preschoolers. Psychological Medicine, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger DA, & Schwartz GE (1990). Distress and restraint as superordinate dimensions of self-reported adjustment: A typological perspective. Journal of Personality, 58(2), 381–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR, Barry CM, & Caldwell KA (2004). Friendships in Middle School: Influences on Motivation and School Adjustment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(2), 195–203. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S, Waller R, & Viding E (2016). Practitioner review: involving young people with callous unemotional traits in treatment–does it work? A systematic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(5), 552–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.