Abstract

Background:

Extended-release (XR) naltrexone can prevent relapse to opioid use disorder following detoxification. However, one of the barriers to initiating XR-naltrexone is the recommendation for a 7–10-day period of abstinence from opioids prior to the first dose.

Objectives:

The current study evaluated the feasibility of an XR-naltrexone induction protocol that can be implemented over 1 week in the outpatient clinic.

Methods:

Participants (N = 44) were seen in the clinic daily. On Day 1, after abstaining from opioids for at least 12 h, they received buprenorphine 6–8 mg. Adjunctive medications (clonidine, clonazepam, zolpidem, trazodone, and prochlorperazine) were dispensed on Days 2–5, while ascending oral doses of naltrexone were given on Days 3–5 starting with 1 mg dose. An injection of XR-naltrexone was given on Day 5, 1 h after receiving and tolerating naltrexone 24 mg.

Results:

Of the 44 participants (38 males), 35 (80%) were heroin users and 9 (20%) used prescription opioids. A total of 26 participants (59%) completed the induction and received their first injection of XR-naltrexone. XR-naltrexone was initiated in 54% (19/35) of heroin users and 78% (7/ 9) of prescription opioid users.

Conclusion:

The results support the feasibility of a week-long outpatient induction onto XR-naltrexone with ascending doses of naltrexone and standing doses of adjunctive medications. By circumventing the need for a protracted period of abstinence and mitigating the severity of withdrawal symptoms experienced during naltrexone titration, this strategy has the potential to increase patient acceptability and access to relapse prevention treatment with XR-naltrexone.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder, XR-naltrexone, opioid, heroin, detoxification, outpatient

Introduction

Opioid use disorder (OUD) continues to be the driving force behind rising rates of drug overdoses in the United States. One of the recent additions to treatment options for OUD is an extended-release preparation of naltrexone (XR-naltrexone), an opioid antagonist approved by the FDA in 2010 as Vivitrol for the prevention of relapse following opioid detoxification (1). The main advantage of XR-naltrexone is the extended duration of its action, protecting individuals from relapse for a month, circumventing the need for daily pill-taking that would often lead to non-adherence with oral naltrexone. Treatment with XR-naltrexone has been associated with improved treatment retention, abstinence from opioids, and reduced craving compared with placebo (1), doubling treatment retention as compared to treatment with oral naltrexone (2). Once initiated, effectiveness of XR-naltrexone is comparable to buprenorphine, another FDA-approved treatment that can be used outside of the specialty treatment setting (3,4).

One of the main barriers to initiating XR-naltrexone in active opioid users is the need for a resolution of physiological dependence from opioids (detoxification) prior to the first naltrexone dose to avoid precipitating withdrawal. The most commonly used strategy for individuals wishing to start XR-naltrexone is an opioid agonist taper, usually 4–7 days of decreasing buprenorphine or methadone doses, followed by 7–10 days of “washout” after the last dose on an opioid (Package Insert for Vivitrol). Unfortunately, many find this period of opioid taper and washout difficult, due to persisting withdrawal symptoms and cravings, and are unable to complete it. This is especially difficult when the detoxification is taking place in an outpatient setting as compared to an inpatient one (5,6). Inpatient treatment is limited in availability and expensive, and outpatient treatment is an important alternative (7). This highlights the need for the development of rapid and effective methods for outpatient initiation of XR-naltrexone.

The desired method would allow to initiate treatment with XR-naltrexone in patients using opioids at the time of evaluation. Such method will be safe and well tolerated, shorter than the standard regimen, and feasible on an outpatient basis. It was previously demonstrated that outpatient transition from heroin or prescription opioid use to XR-naltrexone could be achieved in 7 days, using a regimen of buprenorphine, clonidine and other ancillary medications, and gradual up-titration of oral naltrexone (8). In this method, naltrexone is administered without waiting for opioids to washout beginning with small oral doses which do not precipitate withdrawal but prepare the system to tolerate a large dose of naltrexone given with the injection (9). Here we report a modification of this procedure that shortens it to 5 days as naltrexone is titrated over 3 days rather than 5 days. The goal was to develop a protocol that could be implemented during the Monday–Friday period, a more feasible option within standard outpatient specialty treatment programs and primary care settings.

The primary objective of this open-label clinical trial was to demonstrate the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of a week-long outpatient XR-naltrexone induction procedure. The primary outcome was the proportion of participants that received the first XR-naltrexone injection. Secondary outcomes included opioid withdrawal and craving, opioid and other drug use measured by urine toxicology and self-report, and safety measured by observed and reported adverse events.

Methods

Subjects

We recruited opioid-using participants presenting for treatment at the university-based research clinic between April 2015 and July 2017, during two separate time periods when other studies were not recruiting. Eligible were men and women between 18 and 60 years of age that met DSM-5 criteria for current opioid use disorder of at least 6 months’ duration, supported by urine toxicology positive for opioids, and were seeking treatment with XR-naltrexone. Participants were required to be in otherwise good health, based on complete medical history and physical examination, and to be competent to give written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included current use of methadone or buprenorphine, women who were pregnant, lactating, or unable to use adequate contraceptive methods, individuals with an active medical or psychiatric illness which might make participation hazardous, being physiologically dependent on alcohol or sedatives (other substance use disorders were not exclusionary), having a history of allergic or adverse reaction to any of the study medications, having any chronic organic mental disorder, having a history of accidental opioid drug overdose in the last 3 years, and having a medical condition that requires ongoing opioid analgesia. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and all participants gave written informed consent.

Study procedures and medications

The protocol was organized around the Monday–Friday workweek. Participants who met inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled in the study and signed study consent, which usually took place on Friday before the induction week. During the consent visit, participants received education and instructions to prepare for opioid withdrawal and naltrexone induction. They were asked to abstain from opioids for at least 12 h, beginning Sunday afternoon, and present to the clinic on Monday morning to start treatment with buprenorphine. Participants received a one-day supply of adjunctive medications (clonidine, clonazepam, and zolpidem) to be taken as needed to reduce the discomfort of emerging opioid withdrawal during the initial abstinence.

Participants were asked to come to the clinic daily during the induction week (Monday through Friday), and stay for 1–3 h each day to allow for medication dosing, safety monitoring, and collection of study measures. Vital signs and withdrawal severity were assessed at arrival, before and after administration of any medications, and before departure from the clinic. Participants were given buprenorphine (Day 1), ancillary medication (Day 2–5), and naltrexone (Day 3–5) as per protocol. Table 1 (top panel) summarizes a schedule of standing doses of medications offered to all participants, unless the patient refused, or it was not safe (e.g., clonidine was withheld in case of low blood pressure). All participants received daily psychoeducation about the withdrawal and medication management from a physician and a weekly session with a therapist which included elements of motivational interviewing and relapse prevention therapy.

Table 1.

Study medications given during study days. Top panel represents scheduled (standing) doses (mg) while the bottom line represents the actual doses administered [standing + as needed doses: mean (SD)].a

| Study Day | Buprenorphine | Naltrexone | Clonidineb | Clonazepam | Zolpidem | Trazodone | Prochlorperazine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | 2+2+2 (+2prn) | prn | prn | prn | prn | prn | |

| Day 2 | |||||||

| Day 3 | 1 + 2 | 0.1 qid | 0.5 qid | 10 qHS | 100 qHS | 10 bid | |

| Day 4 | 3 + 3 | ||||||

| Day 5 | 6 + 6 + 12 | ||||||

| Day 1 | 6.6 (2.6) | 0 | 0.11 (0.20) | 0.78 (1.34) | 4.7 (7.0) | 27.8 (61.5) | 8.1 (16.5) |

| Day 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.37 (0.28) | 1.94 (0.34) | 7.7 (4.3) | 51.6 (50.8) | 15.5 (13.4) |

| Day 3 | 0 | 2.5 (2.5) | 0.29 (0.16) | 2.25 (1.63) | 7.2 (5.1) | 72.2 (66.0) | 20.8 (15.7) |

| Day 4 | 0 | 9.5 (6.6) | 0.29 (0.20) | 1.97 (1.01) | 7.3 (7.0) | 65.6 (48.3) | 21.1 (16.7) |

| Day 5 | 0 | 24.8 (5.1) | 0.32 (0.18) | 1.76 (1.30) | 9.6 (8.8) | 64.0 (49.0) | 13.6 (11.4) |

additional doses of adjunctive medications were given as needed for the evening prior to the first dose of buprenorphine, during Days 1–5, and the 1 week after the XR-naltrexone injection.

scheduled clonidine doses were held if SBP < 100

scheduled clonazepam doses were held for excessive sedation

On Day 1 (Monday), after an overnight abstinence from opioids, participants were assessed for withdrawal severity using the COWS (Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale) (10). COWS score of 6 or greater was required before the buprenorphine 2 mg was given, and participants waited in the clinic when necessary for withdrawal to reach that threshold. Additional two doses of buprenorphine 2 mg were given in the clinic at hourly intervals, for a total of 6 mg. An additional 2 mg dose was given to take in the evening at home if withdrawal symptoms persisted. Ancillary medications were given as needed for participants with persistent withdrawal in the clinic on Day 1, despite receiving buprenorphine. On Days 2 through 5, while in the clinic, participants were administered standing doses of clonidine and clonazepam to minimize withdrawal symptoms and anxiety and prochlorperazine to prevent nausea and received additional doses of ancillary medications as needed for persistent withdrawal. At the end of each clinic visit patients were sent home with additional doses of adjunctive medications to manage residual withdrawal and insomnia. Both trazodone and zolpidem were offered as some patients found it beneficial to combine them while others had a preference for one medication over the other.

On Days 3 through 5 oral doses of naltrexone were given in addition to doses of adjunctive medications. Naltrexone was given in two doses, 1 h apart, to assure tolerability of the first daily dose (COWS increases two or less), and the daily dose could be adjusted depending on the clinical situation. On Day 3 after pre-medicating with clonidine, clonazepam, and prochlorperazine, oral naltrexone is started at 1 mg dose, with an additional 2 mg dose administered later if no increase in withdrawal was observed. On Day 4, naltrexone 3 mg is administered followed by an additional 3–9 mg dose as tolerated. On Day 5, naltrexone 6 mg is administered followed by another 6 mg, and 12 mg given at 1-h intervals.

If the total of 24 mg dose oral naltrexone was tolerated without an increase in withdrawal, XR-naltrexone was administered as an intramuscular gluteal injection. In cases where there was an increase in withdrawal (COWS score change >2) after naltrexone doses given on Day 5, participants received additional doses of ancillary medications and XR-naltrexone injection was not given, which happened only in participants who continued using opioids during the induction period. Participants that were unable to complete XR-naltrexone induction, mostly because of continuing opioid use, were offered stabilization on buprenorphine/naloxone and referral to continuing treatment in the community.

Additional doses of clonidine 0.1 mg bid, clonazepam 0.5 mg qid, and zolpidem 10 mg qHS were given as needed for up to 1 week after the first XR-naltrexone injection. All participants were offered one or two additional monthly XR-naltrexone injections, depending on the availability of medication samples, in addition to weekly visits with a psychiatrist and weekly relapse prevention therapy. At the completion of the study all participants were referred for treatment in the community.

All study medications, including the first dose of XR-naltrexone for each participant, were purchased by the investigators and prepared by the research pharmacy at New York State Psychiatric Institute. The pharmacy compounded small doses of oral naltrexone using commercially available product. Samples of XR-naltrexone 380 mg dose (Vivitrol), used for the second and third monthly dose, were provided by Alkermes. All treatment was given at no cost to participants and they were compensated $20 for their time completing assessments at the end of every clinic visit and could earn up to $460 if every study visit was attended.

Measures

Opioid withdrawal symptoms were assessed before and after administration of medications during the study Days 1–5, and at each clinic visit afterward, using the self-reported Subjective Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) (11) and the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) (10) rated by a physician or nurse. The SOWS includes 16 common symptoms of withdrawal rated on a severity scale from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely with a possible score ranging from 0 to 64. The COWS is an 11-item scale completed by a trained observer including several signs of opioid withdrawal with a possible score of 0–48. An additional opioid withdrawal item used the same Likert scale as the SOWS (range 0–4) to evaluate difficulty with sleep. Opioid craving was assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) of heroin/opioid desire intensity since the previous visit (0–100). Drug use was determined on-site using a urine toxicology panel that included tests for opioids, methadone, oxycodone, buprenorphine, cocaine, amphetamines, tetrahydrocannabinol, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates. Also, self-reports of drug use were collected using the Timeline Followback method (12).

Safety

Safety measures included reported and observed adverse events assessed at each study visit. Vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure, oral temperature, and respiratory rate) were performed three or more times daily during the detoxification sessions, and daily at follow-up visits. Physical exams, laboratory parameters (cell blood count, complete metabolic panel, and pregnancy test), and ECG were performed at screening.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and clinical features, and efficacy measures. Measures of opioid withdrawal and craving scores were examined daily over the course of study Days 1 through 5. SOWS, COWS, and opioid craving scales were compared to the baseline scores using paired Student’s t-tests (two-tailed; alpha = 0.05). Number and percent of subjects experiencing adverse events or with clinically significant laboratory, or vital sign findings were also recorded.

Results

Treatment retention

Forty-four participants were enrolled in the study. Table 2 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (N = 44). All participants met the criteria for OUD and had the on-site urine test positive for opioids on study consent day.

Table 2.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of participants (N = 44).

| DEMOGRAPHICS | Percentage/(SD) |

|---|---|

| Age in years | 36.3 (10.33); |

| range 23–60 | |

| Male gender | (38/44) 86.4% |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | (5/44) 11.4% |

| Caucasian | (27/44) 61.4% |

| Hispanic | (10/44) 22.7% |

| Route of drug administration | |

| IN | (18/44) 40.9% |

| IV | (16/44) 36.6% |

| PO | (6/44) 13.6% |

| Smoked | (4/44) 9.1% |

| Type of primary opioid used and the average amount | |

| Heroin | (35/44) 79.5% |

| Amount (#bags of heroin) average (SD) and range | 9.9 (6.7) |

| 2–30 bags | |

| Prescription Opioids | (9/44) 20.5% |

| Amount (mg morphine equivalents) average (SD) and range | 261.4 (303.1) |

| 80–900 mg |

Of the 44 subjects that consented to the study, 26 (59%) successfully completed the induction and received the first XR-naltrexone injection, 25 received their first injection of XR-naltrexone on Day 5 according to the protocol. One participant requested a slower induction after consenting to the study, he received naltrexone 6 mg on Day 5, and because the clinic was closed on the weekend he took naltrexone at home (12 mg on Saturday and 24 mg on Sunday) and returned to the clinic to receive XR-naltrexone on Monday. In total, XR-naltrexone was received by 54.3% (19 out of 35) of heroin users and 77.7% (7 out of 9) of prescriptionopioid users.

Eighteen participants (41%) did not receive the XR- naltrexone – eight dropped out of treatment before receiving the first dose of oral naltrexone (early dropout: Days 1–2) and ten dropped out after receiving oral naltrexone (late dropout: Days 3–5). Of participants who dropped out early, three did not return after consent to start buprenorphine, one was unable to initiate buprenorphine because of continued opioid use, one had increase in withdrawal severity after receiving 4 mg of buprenorphine and dropped out of treatment, and three received buprenorphine but were unable to receive naltrexone because of continued opioid use. Of participants who dropped out late, two were unable to tolerate Day 3 naltrexone dosing, four dropped after receiving Day 4 naltrexone, and four participants were unable to tolerate Day 5 naltrexone. Those patients were referred out to continue buprenorphine maintenance treatment.

The second monthly was administered to 77% (20/ 26) and third injection to 63% (12/19) of participants eligible to receive it as the availability of medication samples was limited.

Opioid withdrawal and craving

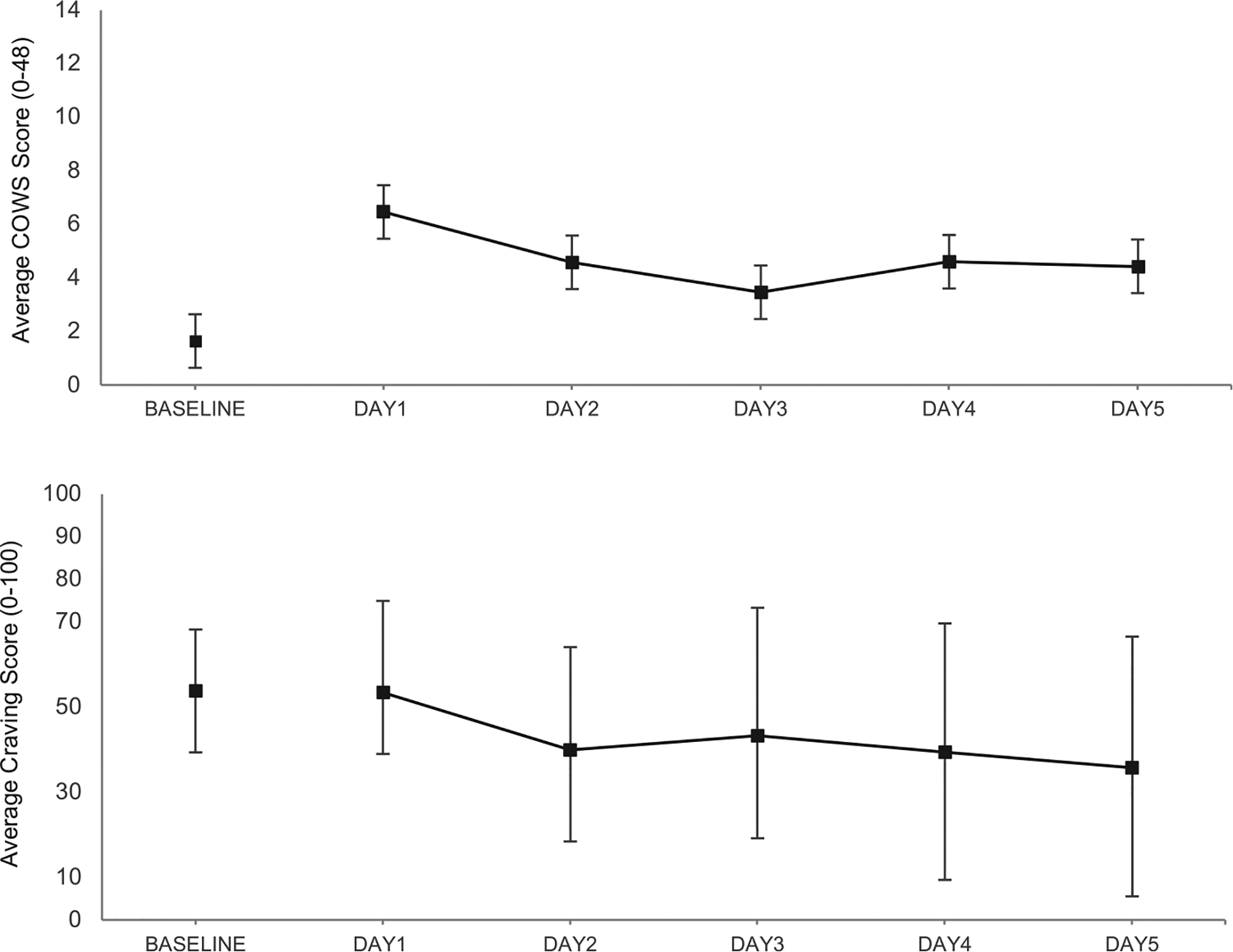

At baseline, during the study consent visit, most patients presented in no or minimal withdrawal, with the average opioid craving of moderate severity. During the 5 days of the study, withdrawal severity in participants that remained in treatment was on average mild or lower (COWS range for mild severity is 5–12). Figure 1 shows COWS withdrawal and craving scores at baseline and throughout the detoxification/induction period. The Clinician-rated withdrawal severity (COWS) was a mean of 4.19 (SD 2.99), with the highest severity on Day 1, right before the first dose of buprenorphine was given. Withdrawal severity decreased over the subsequent 4 days. COWS severity showed a significant decrease between Days 1 and 2 (p = .03), Days 1 and 3 (p = .002), and Days 1 and 4 (p = .047). Participant-rated withdrawal severity (SOWS) was a mean of 24.5 (SD 19.0) and did not change throughout the 5-day treatment period. Rating on the additional insomnia severity item was a mean of 1.69 (SD 1.40) (range 0, not at all, to 4,extremely) and did not significantly change throughout the 5-day treatment period. There was no difference in the insomnia severity during the first 2 days of induction between participants that completed and those that did not complete the XR-naltrexone induction (mean of 1.96 [SD1.34] vs. 1.90 [SD 1.42], respectively). Opioid craving score was on average 43.9 (SD 25.5) (range 0, not at all, to 100, extremely) and significantly decreased between Days 1 and 5 (p = .02).

Figure 1.

Observed daily mean scores (SD) on Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) the top panel and Opiate Craving Scale (VAS) the bottom panel during the 5-days of the protocol.

Opioid use during the study

Of the 44 participants that consented to the study, 17 participants (17/44 or 39%) reported opioid use during the 5 days of induction and 2 participants did not return to initiate Day 1. The number of participants who remained in treatment and reported using illicit opioids during the 5-day detoxification period were 4 on Day 1, 5 on Day 2, 0 on Day 3, 4 on Day 4, and 1 on Day 5. Of the 26 people that received XR-naltrexone, 10 participants (10/26 or 38%) reported using opioids at some point during the induction week but they were able to tolerate increasing doses of naltrexone and received XR-naltrexone.

Overall, 13/26 participants (52%) had a urine toxicology test positive for opioids (morphine or buprenorphine) on Day 5 and were able to receive the XR-naltrexone injection. Of the 13 participants who were positive for opioids on Day 5, 4 (31%), reported using illicit opioids at least once since Day 1. The remaining 13 participants who used illicit opioids during the induction dropped before Day 5.

Medication doses and safety

The actual doses of study medications that participants received (standing plus as needed doses) are summarized in Table 1 (bottom panel). Average daily doses are comparable across study Days 2–5 with the average daily doses of clonidine 0.32 mg, clonazepam 1.98 mg, zolpidem 7.95 mg, Trazodone 63.4, and prochlorperazine 17.8. Doses administered were within target dose ranges outlined in the protocol (Table 1; top panel). There was no indication that clonazepam or zolpidem, given daily in the doses determined by the protocol to take at home during the induction, or after the XR-naltrexone injection, were misused or caused excessive sedation or withdrawal with the need for a taper, based on self-report of participants.

As expected, most of participants experienced adverse events consistent with opioid withdrawal. Eleven of the 44 enrolled participants (25%) reported experiencing one or more adverse events (AE) that were at least moderate in severity. These included (and the % of participants reporting it): diarrhea (9.1%), nausea/vomiting (6.8%), difficulty sleeping (6.8%), irritability (6.8%), muscle cramps/twitching (4.5%), dizziness (4.5%), abdominal pain (4.5%), anxiety (4.5%). No serious adverse events (SAE) or overdoses occurred among study participants during the observation period.

Discussion

Results of this study show that of selected individuals with OUD who are actively using opioids 59% may successfully initiate treatment with XR-naltrexone on an outpatient basis within a 5–7 days workweek. The rate of successful initiation of treatment with XR-naltrexone is even higher, more than 75%, in individuals who are using prescription opioids. Importantly, participants who remained in treatment experienced low levels of withdrawal severity and moderate levels of craving, which remained stable or improved over the 5-day course of in-clinic treatment. Most adverse events were consistent with the syndrome of opioid withdrawal and no SAEs were observed. Adjunctive medications used in this protocol were well tolerated, though might have not been high enough for participants that were not able to initiate treatment with XR-naltrexone. The most common reason for the failure of induction, as reported by participants, was continuing use of illicit opioids and the inability to tolerate increasing doses of naltrexone and for those patients an inpatient treatment setting may be more appropriate.

The 59% rate of XR-naltrexone induction success observed in the present study was comparable to the 56% success rate observed in the accelerated induction, naltrexone-assisted treatment arm in the study of Sullivan et al. (8). Sullivan and colleagues used similar doses of adjunctive medications but a slower 7-day protocol, and the induction rates were comparable with the present study, 46% for heroin and 74% for prescription opioid users. This suggests that the success rates for both protocols are comparable, but the present protocol is shorter and therefore may be more feasible for outpatient treatment settings and less costly to implement. The advantage of a shorter protocol may be particularly relevant for prescription opioid users who have higher induction success rate.

The overall induction success rate in the present study is lower than the 75% rate reported by Mannelli et al. (13) with a 7-day outpatient induction protocol in a sample of 20 individuals with OUD (60% heroin users). Mannelli and colleagues proposed administering buprenorphine during Days 1–3, and starting oral naltrexone on day 1 of the induction but using lower starting doses of 0.25–0.5 mg. However, a recent out-patient, multisite randomized and blinded study that evaluated a protocol modeled on Mannelli et al., comparing the buprenorphine/naltrexone arm to placebo buprenorphine/naltrexone, and placebo/placebo arm with XR-naltrexone injection on Day 8 did not show a difference between groups (14). In this study, 40.5–46% of participants received the first XR-naltrexone dose (56% in prescription opioid and 37% in heroin users), suggesting that with a longer protocol, ancillary medications administered as standing doses may be sufficient to alleviate withdrawal symptoms during the washout from opioids with no added benefit of buprenorphine along with low dose oral naltrexone.

The success rate of XR-naltrexone induction with the present protocol compares favorably with the success rates of standard outpatient methods of detoxification. In a large outpatient study that evaluated 13-day taper of buprenorphine/naloxone vs. a 13-day treatment with clonidine, with ancillary medications available in both groups, only 29% of participants in buprenorphine/naloxone and 5% in clonidine groups were still in treatment on the day 14 with average COWS score of 4.0 (SD 3) and 5.1 (SD 3.2) and craving of 37.7 (SD 20.8) and 57.1 (SD 23.3) in buprenorphine/ naloxone and clonidine groups, respectively (5).

We have designed the present study around the five-day workweek to improve its feasibility as many outpatient treatment programs are not open 7 days a week. The average length of stay in the clinic was around 3 h each day, around 4 h on the day of the XR-naltrexone injection. This length of needed monitoring is comparable to the length of monitoring on the day of buprenorphine induction when done in the clinic, with comparable withdrawal severity. Daily monitoring and observed dosing are important as our anecdotal observations in previous trials show that patients who are not seen daily, and are asked to take oral naltrexone at home, may not be fully adherent with naltrexone. Results of the present study suggest the feasibility and tolerability of a shorter outpatient induction period with daily clinic visits, provided that extended monitoring is available. However, it is important that the protocol offers flexibility, as patients may request for need of additional days to minimize withdrawal severity before the XR-naltrexone is administered.

Almost half of all participants that received XR-naltrexone were also urine-positive for buprenorphine or morphine on the day of the injection. This suggests it may not be necessary to wait 7–10 days since the last opioid use and/or have an opioid-negative urine to be able to receive the naltrexone injection, as it is recommended in the Vivitrol package insert. Moreover, a number of participants who reported using heroin or prescription opioids during the induction, a possible occurrence during the outpatient treatment, were still able to receive the injection as they tolerated gradual titration of oral naltrexone. Some participants were not able to tolerate naltrexone induction, as evidenced by continuing use of opioids or complaints of intolerable withdrawal and for them continuing treatment with buprenorphine may be a better strategy. A naloxone challenge (0.8–1.2 mg i.m.) is also recommended in the package insert to confirm the readiness for XR-naltrexone injection; however, if a patient has tolerated 12.5–25 mg of oral naltrexone, the naloxone challenge may become unnecessary.

We hypothesize that standing or fixed dosing of non-opioid adjunctive medications may be more effective than as needed dosing to minimize withdrawal symptoms during the induction and facilitate completion of the induction. The doses of ancillary medications were comparable across study Days 2–5, and withdrawal severity or craving were stable or decreasing suggesting that patients that remained in treatment tolerated rapid titration of oral naltrexone well. It is possible that higher doses of adjunctive medication might be more effective in facilitating the XR-naltrexone induction. However, use of benzodiazepines or hypnotic agents such as zolpidem requires close safety monitoring and may not be acceptable in some treatment programs on an outpatient basis.

The present study has several limitations including the open-label, uncontrolled, and feasibility-focused study design with limited information about participants who were excluded from the study. The treatment team was very experienced in conducting outpatient naltrexone-induction procedures which may lead to better outcomes. The need for a compounding pharmacy to prepare low doses of naltrexone further limits the generalizability of study results. The open-label design precludes the evaluation of the mechanism by which the proposed protocol contributes to the success of the XR-NTX induction.

Patients responding to advertisements for research treatment, free of charge, may be more motivated than the typical patient with OUD entering treatment and therefore generalizability of results to all patients with OUD may be limited. Compensation that participants received at each study visit might have also played a role to increase treatment adherence as incentives, used as a therapeutic intervention, improve adherence with outpatient treatment utilizing naltrexone (15). Utilizing contingency management strategies may have potential therapeutic value as a part of naltrexone initiation to be studied in future research.

The present study was conducted before it became known that a locally available heroin was contaminated with fentanyl and therefore participants were not tested for fentanyl. It is not clear what proportion of patients might have been exposed to fentanyl and how it affected the outcome as there are anecdotal reports that fentanyl has made initiation of buprenorphine more difficult (16).

Finally, the time effort needed to implement the protocol was significant. This may not be possible in many outpatient addiction treatment programs, but it may be suited to intensive outpatient or partial-hospital programs as extended monitoring of medication response, additional behavioral interventions (17) and psychoeducation groups are likely to further improve outcomes.

In conclusion, the study results support the feasibility and tolerability of a rapid, outpatient regimen for XR-naltrexone induction. By circumventing the need for a protracted period of abstinence this strategy has the potential to increase patient acceptability of, and access to, antagonist therapy. Continued research is needed to improve the success rate of rapid naltrexone initiation, particularly among heroin users.

Funding

This research was supported by NIDA grant [RO1DA030484].

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01377610

Disclosures

Dr. Nunes has participated as an unpaid consultant for Braeburn-Camurus, Pear Therapeutics, and Alkermes, has served as an investigator on a multi-site trial funded by Braeburn-Camurus, and has received medication for NIDA-funded studies from Indivior and Alkermes.

Dr. Bisaga participated as an unpaid consultant to Alkermes, received grant funding (through the institution) from Alkermes, has served as an investigator on a multi-site clinical trial funded by Alkermes, and has received medication for NIDA-funded studies from Alkermes.

Drs. Levin and Mariani, Ms. Mishlen and Mr. Sibai reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1506–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan MA, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M, Carpenter KM, Choi CJ, Mishlen K, Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Nunes EV. A randomized trial comparing extended-release injectable suspension and oral naltrexone, both combined with behavioral therapy, for the treatment of opioid use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:129–37. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17070732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif ZE, Benth JS, Opheim A, Sharma-Haase K, Krajci P, Kunoe N. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:1197–205. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JD, Nunes EV Jr., Novo P, Bachrach K, Bailey GL, Bhatt S, Farkas S, Fishman M, Gauthier P, Hodgkins CC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:309–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32812-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ling W, Amass L, Shoptaw S, Annon JJ, Hillhouse M, Babcock D, Brigham G, Harrer J, Reid M, Muir J, et al. A multi-center randomized trial of buprenorphine-naloxone versus clonidine for opioid detoxification: findings from the national institute on drug abuse clinical trials network. Addiction. 2005;100:1090–100. doi: 10.1111/add.2005.100.issue-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Day E, Strang J. Outpatient versus inpatient opioid detoxification: a randomized controlled trial. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;40:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SAMHSA. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS): 2016 In: Data on substance abuse treatment facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M, Choi CJ, Mishlen K, Carpenter KM, Levin FR, Dakwar E, Mariani JJ, Nunes EV. Long-acting injectable naltrexone induction: a randomized trial of outpatient opioid detoxification with naltrexone versus buprenorphine. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:459–67. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Umbricht A, Montoya ID, Hoover DR, Demuth KL, Chiang CT, Preston KL. Naltrexone shortened opioid detoxification with buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;56:181–90. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253–59. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handelsman L, Cochrane KJ, Aronson MJ, Ness R, Rubinstein KJ, Kanof PD. Two new rating scales for opiate withdrawal. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1987;13:293–308. doi: 10.3109/00952998709001515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption In: Allen JP, Litten RZ, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: psychosocial and biological methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. p. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mannelli P, Wu LT, Peindl KS, Swartz MS, Woody GE. Extended release naltrexone injection is performed in the majority of opioid dependent patients receiving outpatient induction: a very low dose naltrexone and buprenorphine open label trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;138:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisaga A, Mannelli P, Yu M, Nangia N, Graham CE, Tompkins DA, Kosten TR, Akerman SC, Silverman BL, Sullivan MA. Outpatient transition to extended-release injectable naltrexone for patients with opioid use disorder: A phase 3 randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187:171–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nunes EV, Rothenberg JL, Sullivan MA, Carpenter KM, Kleber HD. Behavioral therapy to augment oral naltrexone for opioid dependence: a ceiling on effectiveness? Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:503–17. doi: 10.1080/00952990600918973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bisaga A What should clinicians do as fentanyl replaces heroin? Addiction 2019. doi: 10.1111/add.14522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carroll KM, Weiss RD. The role of behavioral interventions in buprenorphine maintenance treatment: a review. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:738–47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]