Abstract

Although sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has become a standard of care for management of axilla in breast cancer patients, the technique of SLNB is still not well defined. Unlike radioactive sulfur colloid which requires nuclear medicine facilities, methylene blue dye is readily available. The purpose of this study is to validate the use of methylene blue dye alone for SLNB in early breast cancer patients. 60 patients of early breast cancer were randomized to receive either methylene blue alone (Group A-30 patients) or a combination of both methylene blue and radioactive colloid (Group B-30 patients) for detection of sentinel lymph nodes. Sentinel lymph node biopsy was done followed by complete axillary dissection in all patients. In both Groups A and B, sentinel node was identified in all 30 patients, giving identification rate of 100%. In group A, sentinel node was the only positive node in 1 patient, with a false-positive rate of 14.2%. The negative predictive value was 91.3%. The sensitivity of the procedure in predicting further axillary disease was 75% with a specificity of 95.45%. The overall accuracy was 90%. In group B, sentinel node was the only positive node in 2 cases, giving a false-positive rate of 28.7%. The negative predictive value was 95.65%. The sensitivity of the procedure in predicting further axillary disease was 83.33% with a specificity of 91.67%. The overall accuracy was 90%. Although the false-negative rate was slightly higher with methylene blue alone than that using combination (8.6%–4.3%), it was statistically insignificant. Similarly the sensitivity (75%–83.33%), specificity (95.45–91.67%), and negative predictive value (91.3%–95.67%) were also comparable between groups A and B, respectively. Negative predictive value and false-negative rates are comparable, whether blue dye is used alone or a combination of blue dye and radioactive colloid is used. Sentinel lymph node biopsy with blue dye alone is reliable and can be put to clinical practice more widely, even if nuclear medicine facilities are not available in resource constrained centers, so as to reduce long-term morbidity of axillary dissection, with similar oncological outcomes.

Keywords: Sentinel, Breast cancer, Blue dye, Radioactive colloid

Introduction

Controversy has long existed regarding the biologic implications and surgical treatment of regional lymph node metastasis in invasive breast cancer. Axillary lymph node metastases are “indicators but not governors” of outcome in breast cancer. With the advent of sentinel lymph node biopsy and its widespread application, the need for complete axillary evaluation has been questioned [1–9].

The status of the axillary lymph nodes is one of the most important prognostic indicators for overall survival in breast cancer [10]. Axillary lymph node dissection helps in guiding further axillary and adjuvant systemic treatment and has a very low false-negative rate. However the morbidity associated with the procedure including lymphedema (15–30%), neuropathy (78%), hematomas, and seromas (10–52%) so also treatment cost, length of operation, and prolonged inpatient stay is well recognized [11]. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has now become the standard of care for axillary staging of appropriate group of patients; but the technique to be employed is still not standardized.

Methylene blue dye is readily available for use in patients. Radioactive sulfur colloid on the other hand is available only in selected centers with nuclear medicine facilities. The aim of this study was to validate the use of methylene blue dye alone for sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients, as compared to a combination of methylene blue dye and radioactive sulfur colloid. This is more so important in developing countries where radioactive sulfur colloid is not readily available.

Materials and Methodology

The study was conducted over a period of one and half year from June 2015 to December 2016. Preoperative workup included clinical examination, imaging (mammogram and ultrasound of breast), and Tru-cut biopsy from tumor. Patients with biopsy-proven invasive carcinoma were subsequently included. Using USG, nodes were characterized as suspicious, indeterminate, or benign. Lymph nodes with an even cortex measuring < 3 mm were characterized as benign. Lymph nodes with either an even cortex measuring ≥ 3 mm or with focal cortical thickening but with a cortical thickness measurement of < 3 mm were considered indeterminate, and lymph nodes with focal cortical thickening measuring > 3 mm (or with a completely absent fatty hilum) were considered suspicious for metastatic disease [12]. Suspicious or indeterminate nodes underwent USG-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). Inclusion criteria included patients with clinical T stage, T1 and T2 (size less than 5 cm), with no palpable axillary nodes. All patients underwent ultrasound axilla and were included only if they had non-suspicious axillary lymph nodes or suspicious lymph nodes negative FNAC. Both mastectomy and breast conservation surgery (BCS) patients were included. Patients with clinical T stage, T3 and T4; clinically positive axillary lymph nodes; previous surgery in breast or axilla; those who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy; patients with multicentric tumors; and male breast cancer were excluded from study.

Out of the 66 patients identified, 6 were excluded and 60 patients were randomized with computer-generated sequences into two arms (30 each). One arm received methylene blue alone (group A), and the other received both methylene blue and radioactive sulfur colloid (group B) for detection of sentinel lymph nodes (SLNs).

Technique

1) Methylene blue arm (group A): Injected with 5 ml of methylene blue peritumorally in subcutaneous tissue about 10 mins prior to incision and injection site adequately massaged for 5 min.

2) Methylene blue and radioactive colloid arm (Group B): Injected with 1 mCi (mCi) of filtered technetium-99 m sulfur colloid ([99mTc]TSC) in a total volume of 1 mL of normal saline periareolar, intradermally about 2 h prior to surgery and then 10 min prior to incision patient; they were injected with methylene blue (5 ml) in the peritumoral area.

Steps

While performing BCS/mastectomy, sentinel lymph nodes were removed first and sent for histopathological analysis (frozen section). In BCS, patient’s axillary dissection was started first, making a small skin incision just below and parallel to axillary hairline. During mastectomy, superior flap was raised, followed by dissection in axilla. In both the group of patients, gentle dissection was done towards the lateral border of pectoralis major muscle till draining blue lymphatic was identified, which was followed and node removed. In group A, all LNs which were stained blue were removed. In group B, an intraoperative gamma-detecting probe was used to help guide in dissection. SLNs were identified if they are blue, if they have in vivo radioactive counts (hot nodes) at least two times greater than background count of the axilla, or if they had both these characteristics [Fig. 1 and 2]. Radioactive nodes were removed until the background radioactivity of the axilla was lower than 10% of the ex vivo count of the hottest node removed. Nodes that are hard and highly suspicious for metastatic tumor were also removed and defined as SLNs irrespective of radioactivity or blue dye staining. This was followed by wide excision/mastectomy and complete axillary dissection, without waiting for the frozen section report. Histopathological examination (HPE) for sentinel LNs was performed by frozen section and permanent sections with H&E (hematoxylin and eosin), whereas the non-SNs were evaluated by H&E alone. Patients were discharged when fit and asked to follow up with histopathology report.

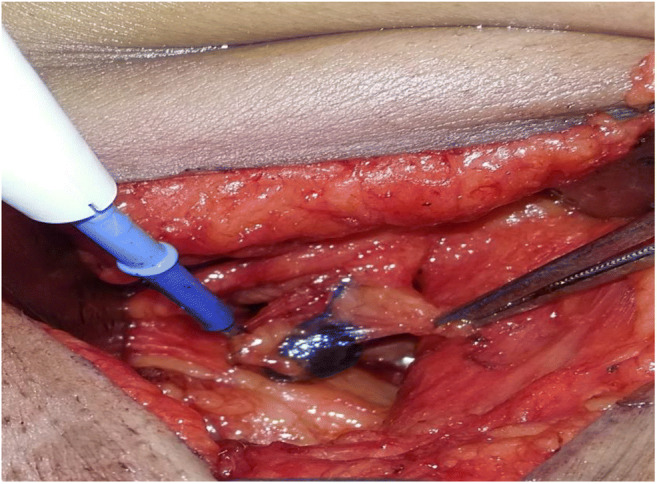

Fig. 1.

Blue sentinel lymph node with draining lymphatic

Fig. 2.

Gamma probe with indicator showing reading of hot node

Fisher’s exact test, chi-squared test, and t test were used to compare data between the two groups. Values of P less than or equal to 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the sentinel lymph node biopsy were analyzed after final histopathology report was available. False negative indicated number of patients with negative sentinel lymph nodes but positive nodes on completion axillary dissection specimen. Negative predictive value (NPV) of test indicated ability to accurately predict node-negative status of patient when sentinel lymph node was negative.

Results

The mean age of patients in group A was 56.6 ± 11.26 years, whereas in group B, it was 53.5 ± 11.05 years. Mean BMI was 23.37 ± 1.58 and 23.23 ± 1.34 in Group A and group B, respectively. The most common histology was invasive ductal cell carcinoma identified in 26 patients in group A and 27 patients in group B. 10 (33.3%) and 14 (46.6%) patients in group A and group B underwent modified radical mastectomy (MRM), respectively, whereas 20 (66.6%) and 16(53.3%) patients underwent breast-conserving surgery (BCS) in groups A and B, respectively. None of the patients experienced any side effects after methylene blue dye injection in either group [Table 1].

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| Group A (methylene blue) | Group B (combined technique) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 30 | 30 |

| Mean age of patients (years) | 53.5 | 54.5 |

| Histology | ||

| 1) IDC | 26 | 27 |

| 2) ILC | 0 | 1 |

| 3) Medullary variant | 2 | 2 |

| 4) Mucinous variant | 2 | 1 |

| Type of surgery | ||

| 1) MRM | 10 | 14 |

| 2) BCS | 20 | 16 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 23.37 | 23.23 |

IDC invasive ductal carcinoma, ILC invasive lobular carcinoma, MRM modified radical mastectomy, BCS breast conserving surgery, BMI body mass index

In both Groups A and B, sentinel node was identified in all 30 patients, with identification rate of 100%. A mean of 3.16 sentinel nodes (range of 1–9) and 3.2 sentinel nodes (range of 1–6) was identified in groups A and B, respectively. The sentinel lymph node was found to contain metastatic disease in 7 cases in both groups. Mean no. of lymph node identified on completion of axillary dissection was 14.5 and 15 in groups A and B, respectively. Concordance between frozen and final histopathological assessment of sentinel lymph nodes was 100% in both groups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Final histopathological (HPE) analysis

| Group A (methylene blue) | Group B (combined technique) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

pT stage pT1 p T2 |

14 (46%) 16 (54%) | 11 (37%) 19 (63%) | > 0.05 |

|

pN stage p N0 N positive |

21(58%) 9 (42%) | 21(58%) 9(42%) | 1 |

| Sentinel lymph identification (%) | 100% | 100% | 1 |

| Mean no. of sentinel lymph node identified | 3.16 | 3.2 | > 0.05 |

| Mean no. of lymph node identified on completion of axillary dissection | 14.5 | 15 | > 0.05 |

| Positive sentinel lymph nodes | 7 (23.33%) | 7(23.33) | 1 |

| Concordance between frozen and final HPE (%) | 100% | 100% | – |

In group A, sentinel node was the only positive node in 1 patient (14.2%). The negative predictive value was 91.3%. The sensitivity of the procedure in predicting further axillary disease was 75% with a specificity of 95.45%. The overall accuracy was 90%. Six patients (85.71%) with a positive sentinel node had further involved non-sentinel axillary nodes. In group B, sentinel node was the only positive node in 2 patients (28.7%). The negative predictive value was 95.65%. The sensitivity of the procedure in predicting further axillary disease was 83.33% with a specificity of 91.67%. The overall accuracy was 90%. 5 patients (71.42%) with a positive sentinel node had further involved axillary nodes [Table 3].

Table 3.

Results of sentinel lymph node localization comparing both groups

| Group A (methylene blue) | Group B (combined technique) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 30 | 30 | |

| Pathological negatives | 23/30 | 22/30 | > 0.05 |

| Negative predictive value (%) | 91.3 | 95.65 | > 0.05 |

| False negative (%) | 2/23–8.6% | 1/23–4.34% | > 0.05 |

| Only SN positivity (%) | 1/7–14.2% | 2/7–28.57% | > 0.05 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 75 | 83.33 | > 0.05 |

| Specificity (%) | 95.45 | 91.67 | > 0.05 |

| Accuracy (%) | 27/30–90% | 27/30–90% | 1 |

SN sentinel node

Discussion

SLNB is a minimally invasive staging tool in node-negative patients with proven technical feasibility and reproducibility. Its advantages include minimal tissue dissection, availability of limited tissue for focused histopathological evaluation as also low incidence of lymphedema, and arm morbidity by avoiding ALND in SLN-negative patients. The two most common methods for detecting sentinel lymph nodes are by using either radioactive tracer or a blue dye. Both these methods have undergone technical refinements over many years. In 1996, Albertini first reported his series using combination of radioactive tracer and dye for sentinel lymph node biopsy [13]. Since then, many studies have recommended combination technique for SLNB [11, 14–20]. However concerns regarding availability of nuclear medicine facilities have dampened its widespread use in developing countries. With this study and literature review, we have tried to address this debatable topic.

The two arms in our study were comparable in terms of age, BMI, predominant histology on HPE, and type of surgery performed (modified radical mastectomy versus breast-conserving surgery). In present study, identification was 100% irrespective of the age in both groups. The results from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-32 trial [21] showed a statistically significant, but not clinically relevant, difference in identification rates by 49 years of age or less versus 50 years of age or more. Similarly, the mean BMI did not affect the identification of sentinel lymph nodes in both groups. Some other studies have shown progressive increase in failure rate with increase in BMI above 26 [22].

Blue Dye-Only Group (Group A)

The type of vital dye used for SLNB varies in different studies. We prefer methylene blue as it is safe, readily available, and inexpensive, and studies have shown it to be equivalent to isosulfan blue [23, 24]. The identification rate and sensitivity in our study using methylene blue dye alone were 100% and 75%, respectively, which is comparable to similar studies in which blue dye was also used [18, 25]. The negative predictive value in our study (91.3%) was also comparable to other studies using blue dye [11, 16, 25, 26]. The false negative (8.6%) was better than other studies using blue alone [11, 18, 26] [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparing results of blue dye alone group (group A)

| Author | Year | No. of patients | Success (%) | Sensitivity (%) | NPV (%) | False negative (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morrow [29] | 1999 | 50 | 88 | 95 | – | – | 96 |

| Motomura[18] | 2001 | 93 | 84 | 81 | 93 | 19 | 95 |

| Cserni [30] | 2002 | 76 | 92.1 | 89.6 | 81.5 | 10.4 | 92.9 |

| Radovanovic[11] | 2004 | 50 | – | 82 | 86.9 | 17.6 | 68 |

| Varghese [25] | 2007 | 173 | 96 | 75 | 96 | 3.7 | 87 |

| Present study | 2019 | 30 | 100 | 75 | 91.3 | 8.6 | 90 |

NPV negative predictive value

Combination Group (Group B)

All the patients in combination group had at least one sentinel lymph node identified. This is better than or comparable to other studies using combination technique [17, 18, 25]. The negative predictive value (95.65%) and false negativity which are the most important determinants of efficacy of technique were similar to other studies [11, 25]. However, the sensitivity using combination technique (83.3%) was less as compared to other studies [11, 18, 27]. This may be in part related to smaller sample size of our study [Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparing results of combination group (group B)

| Author | Year | No. of patients | Success (%) | Sensitivity (%) | NPV (%) | False negative (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morrow[29] | 1999 | 42 | 86 | 97 | – | _ | 96 |

| Motomura[18] | 2001 | 138 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| Cserni [30] | 2002 | 72 | 100 | 96.7 | 97.7 | 3.3 | 98.6 |

| Radovanoic [11] | 2004 | 100 | – | 95 | 95 | 4.5 | 83 |

| Varghese [25] | 2007 | 156 | 98 | 70 | 96 | 4 | 84 |

| Present study | 2019 | 30 | 100 | 83.3 | 95.6 | 4.34 | 90 |

NPV negative predictive value

Comparing Group A and Group B

In the present study, whether blue was used alone or a combination was used, the identification of sentinel lymph nodes was 100%. In the multi-institutional ACOSOG Z0010 trial with 5237 patients, the percentage of failed SLNB with blue dye alone was 1.4%, and combination was 1.2% (P = 0.28), supporting the observation that each of these techniques is highly successful in experienced hands with no real difference in accuracy [28]. The mean number of sentinel lymph nodes identified was similar in both group A and group B in our study (3.16 vs 3.2). The probable reason for higher lymph node yield in our study as compared to other studies [11, 18, 25, 28–30] may be a more thorough search for not only hot and blue nodes but also any other palpable node in the axilla. Although the false-negative rate using dye alone was higher than that using combination (8.6% vs 4.3%), it was statistically insignificant. Similarly, the sensitivity (75%–83.33%), specificity (95.45–91.67%), and negative predictive value (91.3%–95.67%) were also comparable between groups A and B, respectively, and were statistically insignificant (p > 0.05).

Studies trying to compare these two techniques have had conflicting results. Whereas two well-conducted randomized trials by Morrow et al. and Varghese et al. [25, 31] have shown no significant difference in outcomes, few older studies [11, 18, 30, 31] have shown better results with combination. Notably in many of this studies [18, 30, 31], SLNB was performed with dye alone in initial cases, and radiocolloid was subsequently added to dye in later cases. The probability that dye alone patients performed inferiorly as they were part of learning curve of the surgeons cannot be ruled out. All surgeons in our study had an experience of minimum of 20 cases of SLNB before study cases were operated. In one of these studies [30], the learning phase cases were excluded from analysis of dye alone group, but still combination group performed better. However, on analyzing blue, hot, or both hot and blue sentinel nodes separately, the number of blue staining positive sentinel lymph node was equal to those that were hot (94.1%). Thus the ability to detect positive sentinel lymph nodes appears comparable despite study showing higher accuracy with combination. Moreover, being a non-randomized study, bias cannot be ruled out.

Few have argued for radiocolloid use in that it allows use of preoperative lymphoscintigraphy scan in localizing hot nodes [18, 30]. However, practically its only advantage may be with respect to detection of extra-axillary nodes, the value of which is debatable [32–34]. Use of intraoperative gamma probe and additional preoperative lymphoscintigraphy mapping will merely increase the cost of SLNB without any tangible benefits [35–37]. Other mentioned advantages include a more focal dissection guided by gamma probe in the region of hot spot [18]. However, as the combination is used, it is necessary that attempts are made to identify the blue draining lymphatics as well, if not identified during dissection of hot spot. Thus the extent of dissection essentially remains the same if not more. Moreover, few surgeons may avoid detailed search for blue nodes if adequate number of hot nodes were identified, decreasing the number of identified blue SLNs [31]. Besides the cost of radiocolloid and gamma probe [29], waiting time following administration of radiocolloid requires that patient cannot be posted as first case in morning. This is an inconvenience for both the surgeon and the patient. Although it can be partly overcome by injecting the dye on previous day, it increases the hospital stay by a day. The use of radioactivity also requires a coordinated effort between the surgical and nuclear medicine teams which may not always be possible [38].

There are certain limitations in our study. Firstly, we did not label and analyze each node separately as being blue, hot, or both. Secondly, the sample size was considerably small, diminishing the power of our study. Although many centers have moved on to combination technique, consideration should be given to use blue dye alone whenever radioactive tracer is not available instead of accepting the high morbidity of complete axillary dissection. Cost issues, especially in countries where most of the population does not have insurance cover, should not limit the use of SLNB. It is essential that the surgeon adapts to the facilities available and at the same time be oncologically sound.

Conclusions

Negative predictive value and false-negative rates are comparable, whether blue dye is used alone or a combination of blue dye and radioactive colloid is used. Sentinel lymph node biopsy with blue dye alone is reliable and can be put to clinical practice more widely, even if nuclear medicine facilities are not available in resource-constrained centers, so as to reduce long-term morbidity of axillary dissection.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cady B. Lymph node metastases. Indicators, but not governors of survival. Arch Surg. 1984;119:1067–1072. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390210063014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, et al. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1522–1530. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartgrink HH, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Bonenkamp JJ, Klein Kranenbarg E, Songun I, Welvaart K, van Krieken J, Meijer S, Plukker JT, van Elk P, Obertop H, Gouma DJ, van Lanschot J, Taat CW, de Graaf PW, von Meyenfeldt M, Tilanus H, Sasako M. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: who may benefit? Final results of the randomized Dutch gastric cancer group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2069–2077. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pezim ME, Nicholls RJ. Survival after high or low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during curative surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1984;200:729–733. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198412000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slingluff CL, Jr, Stidham KR, Ricci WM, et al. Surgical management of regional lymph nodes in patients with melanoma. Experience with 4682 patients. Ann Surg. 1994;219:120–130. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199402000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisenburger T. H. Effects of postoperative mediastinal radiation on completely resected stage II and stage III epidermoid cancer of the lung. LCSG 773. Chest. 1994;106(6):297S–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gervasoni JE, Jr, Sbayi S, Cady B. Role of lymphadenectomy in surgical treatment of solid tumors: an update on the clinical data. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2443–2462. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucci A, Jr, Kelemen PR, Miller C, III, et al. National practice patterns of sentinel lymph node dissection for breast carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:453–458. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00798-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asselius G. De lactibus sine ladeis venis. Medilanis, apud lob Bidellium: Milan; 1627. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baiba J. Grube and Armando E. Giuliano (2009) Breast. Comprehensive management of benign and malignant diseases. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences ,: Chapter 55. Lymphatic Mapping and Sentinel Lymphadenectomy for Breast Cancer ;971–1006

- 11.Radovanovic Z, Golubovic A, Plzak A, Stojiljkovic B, Radovanovic D. Blue dye versus combined blue dye radioactive tracer technique in detection of sentinel lymph node in breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30(9):913–917. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mainiero MB, Cinelli CM, Koelliker SL, Graves TA, Chung MA. Axillary ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration in the preoperative evaluation of the breast cancer patient: an algorithm based on tumor size and lymph node appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(5):1261–1267. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 1996;276:1818–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mariani G, Villa G, Gipponi M, et al. Mapping sentinel lymph node in breast cancer by combined lymphoscintigraphy, blue dye, and intraoperative gamma-probe. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2000;15:245–252. doi: 10.1089/108497800414338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doting M, Jansen L, Niewig O, et al. Lymphatic mapping with intralesional tracer administration in breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2000;88:2546–2552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imoto S, Hasebe T. Initial experience with sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer at the National Cancer Center Hospital East. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1999;29:11–15. doi: 10.1093/jjco/29.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMasters KM, Tuttle TM, Carlson DJ, Brown CM, Noyes RD, Glaser RL, Vennekotter DJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer: a suitable alternative to routine axillary dissection in multi-institutional practice when optimal technique is used. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(13):2560–2566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motomura Kazuyoshi, Inaji Hideo, Komoike Yoshifumi, Hasegawa Yoshihisa, Kasugai Tsutomu, Noguchi Shinzaburo, Koyama Hiroki. Combination technique is superior to dye alone in identification of the sentinel node in breast cancer patients. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2001;76(2):95–99. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200102)76:2<95::aid-jso1018>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frisell J, Bergqvist L, Liljegren G, et al. Sentinel node in breast cancer—a Swedish pilot study of 75 patients. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:179–183. doi: 10.1080/110241501750099311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tafra L, Lannin DR, Swanson MS, et al. Multicenter trial of sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer using both technetium sulfur colloid and isosulfan blue. Ann Surg. 2001;233:51–59. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, et al. Technical outcomes of sentinel-lymph-node resection and conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in patients with clinically node-negative breast cancer: Results from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:881–888. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Galimberti V, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy to avoid axillary dissection in breast cancer with clinically negative lymph-nodes. Lancet. 1997;349:1864–1867. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eldrageely K, Vargas MP, Khalkhali I, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping of breast cancer: a case-control study of methylene blue tracer compared to isosulfan. Am Surg. 2004;70:872–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blessing W, Stolier A, Teng S, et al. Comparison of methylene blue and isosulfan blue dyes for sentinel node mapping in breast cancer: a trial born out of necessity. Am J Surg. 2002;184:341–345. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varghese P, Mostafa A, AbdelRahman AT, Akberali S, Gattuso J, Canizales A, Wells CA, Carpenter R. Methylene blue dye versus combined dye radioactive tracer technique for sentinel lymph node localisation in early breast. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(2):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan A, Howisey R, Aldape H, et al. Initial experience in a community hospital with sentinel lymph node mapping and biopsy for evaluation of axillary lymph node status in palpable invasive breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1999;72:24–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199909)72:1<24::aid-jso6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smillie T, Hayashi A, Rusnak C, et al. Evaluation of feasibility and accuracy of sentinel node biopsy in early breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2001;181:427–443. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00613-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cote R, Giuliano AE, Hawes D, Ballman KV, Whitworth PW, Blumencranz PW, et al. ACOSOG Z0010: a multicenter prognostic study of sentinel node (SN) and bone marrow (BM) micrometastases in women with clinical T1/T2 N0 M0 breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(Suppl. 18):CRA504. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrow M, Rademaker AW, Bethke KP, et al. Learning sentinel node biopsy: Results of a prospective randomized trial of two techniques. Surgery. 1999;126:714–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cserni G, Rajtar M, Boross G, Sinko M, Svebis M, Baltas B. Comparison of vital Dye guided lymphatic mapping and dye plus gamma probe guided sentinel node biopsy in breast cancer. World J Surg. 2002;26:592–597. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cavanese G, Gipponi M, Catturich A, et al. Sentinel lymph nodemapping in early-stage breast cancer: technical issues and results withvital blue dye mapping and radio-guided surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2000;74:61–68. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200005)74:1<61::aid-jso14>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klauber-DeMore N, Bevilacqua JL, Van Zee KJ, Borgen P, Cody HS. Comprehensive review of the management of internal mammary lymph node metastases in breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:547–555. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen RC, Lin NU, Golshan M, Harris JR, Bellon JR. Internal mammary nodes in breast cancer: diagnosis and implications for patient management—a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4981–4989. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dome’nech-Vilardell A, Baje’n MT, Benítez AM, Ricart Y, Mora J, Rodríguez-Bel L, et al. Removal of the internal mammary sentinel node in breast cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30:962–970. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328330addf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun X, Liu JJ, Wang YS, Wang L, Yang GR, Zhou ZB, Li YQ, Liu YB, Li TY. Roles of preoperative lymphoscintigraphy for sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40(8):722–725. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burak WE, Jr, Walker MJ, Yee LD, Kim JA, Saha S, Hinkle G, et al. Routine preoperative lymphoscintigraphy is not necessary prior to sentinel node biopsy for breast cancer. Am J Surg. 1999;177:445–9. 11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMasters KM, Wong SL, Tuttle TM, Carlson DJ, Brown CM, Dirk Noyes R, et al. Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy for breast cancer does not improve the ability to identify axillary sentinel lymph nodes. Ann Surg. 2000;231:724–31. 12. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200005000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox CE, Haddad F, Bass S, Cox JM, Ku N, Berman C, et al. Lymphatic mapping in the treatment of breast cancer. Oncology. 1998;12:1283–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]