Abstract

Head and neck cancers usually occur in the elderly age group and about half of the cases occur at the age > 60 years with majority detected in an advanced stage with increased morbidity and decreasing compliance to therapy. Since there are limited data available for the adequate treatment of elderly head and neck cancer patients, we proposed a study to analyze tolerance and response based on age, site, modality of treatment received, and implication of nutrition vs weight loss during treatment. Fifty-five patients were enrolled in this study, which was conducted between November 2015 and April 2017, and those who met the eligibility criteria were evaluated with a detailed history and physical examination, and biochemical, pathological, and radiological investigations. Patients were staged based on TNM staging and treated as per the standard guidelines. Patients were assessed with the weekly routine blood investigation, weight loss, and toxicity. The response was assessed after 6 weeks and documented as per RECIST criteria. 52/55 (94.5%) patients completed the treatment, and 48/55 (92.3%) had a complete response at 6 weeks (p value 0.000) with a mean treatment duration of 46.67 days and mean weight loss of 5.44 kg with 55.4% having GR-II mucositis, 40% having GRIII mucositis at the time of completion of treatment. Sixty-eight percent having GRII and 38.2% having GR I dermatitis and 80% had moderate pain. Subgroup analysis was done based on age, site, and treatment modality. Patients were also assessed for nutrition vs weight loss. We concluded that elderly patients tolerate and respond well to radical treatment with acceptable toxicities; hence, age should not be a barrier to decide treatment.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Elderly, Radiotherapy

Introduction

The incidence of head and neck cancer in elderly patients is rising all over the world and in India too. Head and neck cancer usually occurs in old age. About half of the cases are detected after the age of 60 years. As per data published by the government of India in 2011 under the heading “Situation analysis of the elderly in India”, cut-off age for defining the elderly is kept at 60 years [1]. Head and neck cancers are commonly treated with combined modalities, and among them, radiotherapy has a vital role because of its complex anatomical relation to important anatomical structures, the function of which should be preserved for a good quality of life. Sequencing of multimodality treatment in case of head and neck cancers depends on site, size, stage, comorbidities, and general condition but not on age. It is assumed that elderly patients have reduced tolerance to multimodality therapy due to associated comorbidities, multiorgan dysfunction, and underestimation of life expectancy, which may lead to under treatment. The newly detected cases of head and neck cancers in geriatric are estimated to cross 60% by 2030 [2]. The consensus on managing elderly patients with head and neck cancer is not well established. These head and neck cancers are commonly detected in advanced stages (III and IV) which need more than one treatment modality [3]. However, combined modality treatment leads to reduced tolerance in elderly patients due to increased toxicity and morbidity. These are the factors which may lead to compromise in the treatment of elderly patients with head and neck cancers, and importantly, they are not included in major randomized trials on which treatment guidelines are based; in a meta-analysis of 93 clinical trials, only 4% of patients were > 70 years [4] There is limited data available regarding the elderly head and neck cancer patient’s compliance with treatment and response assessment. Hence, we have conducted a study to assess whether:

Elderly patients will have increased toxicity and decreased tolerance to treatment

Decreased quality of life after radical treatment compared with younger cohort

Influence of other related factors specific to elderly patients like comorbidities, nutritional support, treatment duration in the tolerance, and response to treatment

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The study design is a longitudinal follow-up study.

Source of Study Subjects

Biopsy-confirmed head and neck cancer patients of 60 years and above undergoing radical chemoradiation at our medical college and hospitals from November 2015 to April 2017 were the subjects of this study.

Rationale for Sample Size

Based on the literature review, a study conducted by Vivek Tiwari et.al. (2015) had observed that the treatment tolerance of concurrent chemotherapy was 70.8%. In the present study, expected similar results with a 95% confidence level and 17% of relative precision requires a sample size of 55.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics of treatment tolerance and response analyses were presented in terms of percentage, and its 95% confidence interval was estimated.

The chi-square test was used to find the association between the age, sex, stage, tolerance, and response.

Inclusion Criteria

Age 60 years and above.

Patients receiving radiation therapy for histologically proven head and neck malignancies with radical intent.

Exclusion Criteria

Patient with previous history of irradiation.

Severe uncontrolled comorbidities.

Postoperative cases.

Method

After obtaining the ethical committee approval, all eligible patients, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, were enrolled and informed consent for participation was taken. After a detailed history and physical examination, including the weight of the patient, baseline investigations which include routine blood counts, biopsy, CT scans/PET CT scan/MRI scan, and metastatic workup were done. Patients were appropriately staged according to TNM staging. Radiation therapy planning was done in the supine position with a thermoplastic mask and simulated by CT scan. Radiation treatment delivery was by conformal radiotherapy to a dose of 66–70 Gy in conventional fractionation with or without chemotherapy. Patients were assessed with weekly routine blood investigation, weight monitoring, and toxicity and documented as per common toxicity criteria version 2.0. Assessment of response would be done at the end of 6 weeks post-treatment and documented as per RECIST criteria. The pain was measured according to the visual analog scale and graded as mild (VAS 0–3) moderate [4–6], and severe [7–10].

Statistical Analysis of the Data

Data were analyzed using statistical software, SPSS Inc. Release 2009.PASW statistics for windows version 18.0, Chicago. The p value of < 0.05 was considered for statistical significance.

Variables like age, gender, diagnosis, stage, site, comorbidities, technique, weight loss, and treatment duration of the tumor were summarized using percentage, mean and standard deviation. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to find the correlation between age with treatment tolerance, age with response, radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy with response and tolerance, site and stage vs tolerance and response, age with weight loss, technique with tolerance and response, comorbidities with tolerance and response. Acute toxicities were expressed in terms of percentage according to grade, at the time of completion of treatment.

Results

Demographic Details (Table 1)

Table 1.

Demographic details of the patients

| Parameters | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | ||

| 60–70 | 38 | 69.1 |

| 70–80 | 13 | 23.6 |

| More than 80 | 4 | 7.3 |

| Sex distribution | ||

| Male | 50 | 90.9 |

| Female | 5 | 9.1 |

| Site wise distribution | ||

| Oral cavity | 3 | 5.5 |

| Oropharynx | 19 | 34.5 |

| Hypopharynx | 18 | 32.7 |

| Larynx | 12 | 21.8 |

| Nasopharynx | 3 | 5.5 |

| Stage wise distribution | ||

| I | 2 | 3.6 |

| II | 7 | 12.7 |

| III | 18 | 32.7 |

| IVA | 23 | 41.8 |

| IVB | 5 | 3.1 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Yes | 14 | 25.5 |

| No | 41 | 74.5 |

The mean age of the study population was 66.5 years, with age ranging from 60 to 93 years. Fifty were males and 5 were females. 34.5% of the cases had oropharyngeal malignancies forming the majority with 32.7% and hypopharyngeal malignancies being the second most common diagnosis.

Stage Wise Distribution of Cases

The stage IVA being the most common stage consists of 41.8% followed by stage III consisting of 32.7%, stage II 12.7%, stage I 3.6%, and stage IVB 3.1%.

Frequency of Comorbidity

74.5% of Patients had no associated comorbidities and only 25.5% of patients had comorbidities.

Treatment-Related Factors (Table 2)

Table 2.

Treatment details of the patients

| Techniques used for radiotherapy | ||

| 3DCRT | 7 | 12.7 |

| IMRT | 44 | 80 |

| IGRT | 2 | 3.6 |

| VMAT | 2 | 3.6 |

| Duration of treatment completion | ||

| Less than 55 days | 49 | 89.1 |

| More than 55 days | 2 | 3.6 |

| Default | 4 | 7.3 |

| Nutritional techniques | ||

| Peg tube | 16 | 29.1 |

| Ryles tube | 3 | 5.5 |

| No intervention | 36 | 65.5 |

| Frequency of patient who received chemotherapy | ||

| Completed | 33 | 60 |

| Incomplete | 10 | 18.2 |

| Not planned | 12 | 21.8 |

Peg tube percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, 3DCRT 3-dimension conformal radiotherapy, IMRT intensity-modulated radiotherapy, IGRT image-guided radiotherapy, VMAT volumetric-modulated arc therapy

Techniques Used for the Treatment

80% of patients were treated with IMRT, 12.7% of the patients were treated by 3DCRT, and 3.6% of patients were treated with VMAT and IGRT each.

Duration of the Treatment Completion

The mean overall treatment time is 46.67 days with 89.1% completed treatment within 55 days and 3.6% of patient completing in more than 55 days.

Nutritional Intervention during the Treatment

Out of 55 patients, 16 patients (5.5%) underwent Ryle’s tube insertion, 16 underwent percutaneous gastrostomy before starting the treatment, and 36 patients (65.5%) did not receive any intervention during the treatment.

Frequency of Patient who Received Chemotherapy

Thirty-three patients completed planned chemotherapy and 12 patients received only radiotherapy, and 10 patients did not complete the planned chemotherapy.

Tolerance to Treatment (Table 3)

Table 3.

Results for the tolerance of the treatment

| Tolerance to the treatment | |||||

| Treatment | Frequency | Percentage | |||

| Complete | 52 | 94.5 | |||

| Incomplete | 3 | 5.5 | |||

| Tolerance to chemoradiation vs radiotherapy | |||||

| Radiotherapy | |||||

| Complete | Incomplete | Total | |||

| Chemo | Completed | 33 | 0 | 33 | P = 0.045 |

| Incomplete | 8 | 2 | 10 | ||

| Not planned | 11 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Age group wise tolerance to treatment | |||||

| Treatment | |||||

| Age | Complete | Incomplete | Total | ||

| < 70 | 36 | 2 | 38 | ||

| 70–80 | 13 | 0 | 13 | ||

| > 80 | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Total | 52 | 3 | 55 | ||

Fifty-two patients completed the radiation treatment out of 55 patients constituting 94.5%.

Tolerance to Chemoradiotherapy vs Radiotherapy

Out of 33 patients who received chemoradiation, all 33 patients completed the treatment; out of 12 who were planned only for radiotherapy, 11 completed the treatment; and among those who discontinued chemotherapy, 8 patients completed treatment; thus, making the patients who received only radiotherapy tolerate the treatment better with p value 0.045.

Age Group with Tolerance of Treatment

Out of 38 patients aged less than 70 years, 36 completed the treatment; out of patients aged 70–80 years, 13 out of 13 completed the treatment; and 3 out of 4 patients aged more than 80 years completed the treatment.

Response to Treatment After 6 Weeks According to RECIST Criteria (Table 4)

Table 4.

Results for the response to the treatment

| Response to the treatment after 6 weeks of completion | ||||||

| Response | Frequency | Percentage | ||||

| Complete | 48 | 92.3 | ||||

| Partial | 4 | 7.7 | ||||

| Persistent | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Progressive | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Age group with response to treatment | ||||||

| Response | ||||||

| Complete | Partial | Defaulted | Total | |||

| Age | < 70 | 35 | 2 | 1 | 38 | |

| 70–80 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 13 | ||

| > 80 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Total | 48 | 5 | 2 | 55 | ||

| Site wise response to the treatment | ||||||

| Response | ||||||

| Site | Complete | Partial | Persistent | Progressive | Defaulted | Total |

| Oral cavity | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Oropharynx | 17 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

| Hypopharynx | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Larynx | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Nasopharynx | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 48 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 55 |

| Response to chemoradiation vs radiotherapy | ||||||

| Response | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | Complete | Partial | Defaulted | Total | ||

| Completed | 31 | 2 | 0 | 33 | ||

| Incomplete | 7 | 2 | 1 | 10 | ||

| Not planned | 10 | 1 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Total | 48 | 5 | 2 | 55 | ||

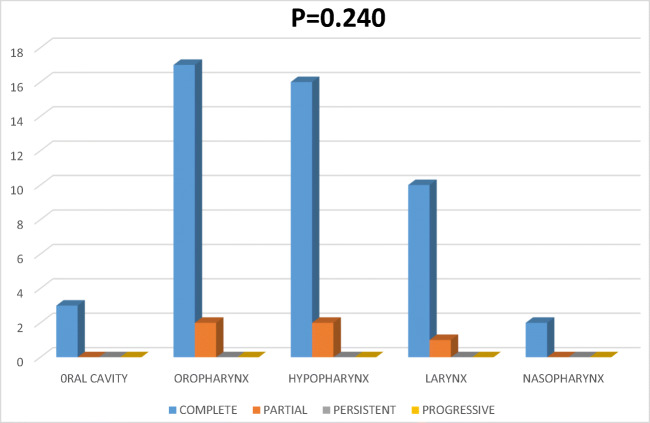

Forty-eight patients (92.3%) had a complete response 6 weeks after the treatment, 4% had partial response, and none had persistent and progressive disease. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Graph showing response to treatment at 6 weeks

Age Group with Response to Treatment

Thirty-five patients out of 38 between the age group of 60–70 years showed complete response, 10 out of 13 patients showed complete response, and 3 patients showed partial response between 70 to 80 years, and 3 out of 4 patients showed complete response and default treatment among > 80 years of age group.

Site Wise Response Rate to the Treatment (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Graph showing site vs response

Among 19 oropharyngeal carcinoma patients, 17 showed complete response and 2 showed partial response. Among 18 patients of hypopharyngeal carcinoma, 16 showed complete response and 2 showed partial response. Three out of 3 oral cavity carcinoma patients showed complete response and 10 out of 12 larynx carcinoma patients showed complete and 1 showed partial response and 2 out of 3 nasopharyngeal carcinomas patient showed a complete response.

Frequencies of Toxicities at the Time of Completion of Treatment (Table 5)

Table 5.

Frequency of acute toxicities during the treatment

| Mucositis | ||

| Grade | Frequency | Percentage |

| Grade 1 | 3 | 5.5 |

| Grade 2 | 30 | 54.5 |

| Grade 3 | 22 | 40.0 |

| Total | 55 | 100.0 |

| Dermatitis | ||

| Grade | Frequency | Percentage |

| Grade 0 | 1 | 1.8 |

| Grade 1 | 21 | 38.2 |

| Grade 2 | 33 | 60.0 |

| Total | 55 | 100.0 |

| Pain | ||

| Grade | Frequency | Percentage |

| Mild | 5 | 9.1 |

| Moderate | 44 | 80.0 |

| Severe | 6 | 10.9 |

| Total | 55 | 100.0 |

| Weight loss | ||

| Weight loss | Frequency | Percentage |

| < 5 kg | 29 | 52.7 |

| 6–10 kg | 21 | 38.2 |

| 11–15 kg | 5 | 9.1 |

| Total | 55 | 100.0 |

MUCOSITIS

54.5% patients had grade ii and 40% patient had grade iii mucositis at the time of completion of the treatment.

Dermatitis

Sixty percent of patients were having grade ii dermatitis, and 38.2% were having grade i dermatitis at the time of completion of the treatment.

Pain

Eighty percent of the patients had moderate pain, 10.9% were having severe pain, and 9.1% of patients had mild pain at the time of completion of the treatment.

Weight Loss

Mean weight loss of the study group was 5.44 kg with 38.1% of patients lost 6–20 kg, 52.1% lost less than 5 kg, and 9.1% of patients lost more than 11 kg.

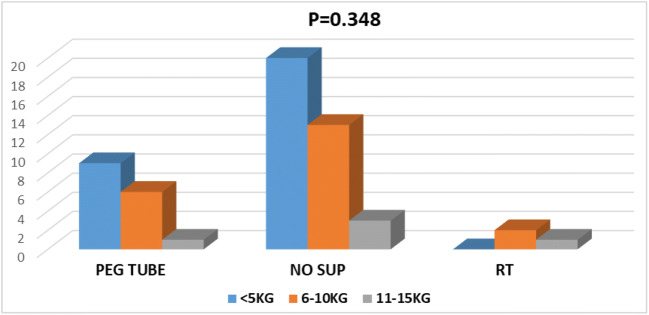

Feeding Procedure vs Weight Loss (Table 6)

Table 6.

Feeding procedures vs weight loss

| Wt loss | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding procedure | < 5KG | 6–10KG | 11–15KG | |

| Peg tube | 9 | 6 | 1 | 16 |

| No sup | 20 | 13 | 3 | 36 |

| RT | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 29 | 21 | 5 | 55 |

Out of 36 patients without any feeding procedure, 20 patients lost less than 5 kg, 13 patients lost 6–10 kg, and 3 patients lost more than 11 kg (Fig. 3). In 16 patients with PEG tube feeding, 9 patients lost less than 5 kg, 6 patients lost 6–10 kg, and 1 lost more than 11 kg. Among 3 patients with RT tube, 2 lost 6–10 kg and 1 lost > 11kg.

Fig. 3.

Graph showing feeding procedure vs weight loss

Discussion

Head and neck cancer pose a major burden among all cancers in India and commonly occurs in the 5th and 6th decade of life due to the increased duration of exposure to tobacco consumption or smoking. There is a thought that since elderly patients may not tolerate radical treatment because of multiorgan compromise, associated comorbidity and considering the survival and lack of social and economic support, and dependency in old age, they are denied of undergoing aggressive treatment approach like younger counterparts. Our study was conducted to assess the tolerance of radical radiation treatment to elderly head and neck cancer patients. We analyzed 55 eligible patients prospectively as compared with similar retrospective study by Vivek Tiwari et al. [5] which analyzed 112 patients of mean age 70.04 years. The mean age in the study is 66.5 years. And similar prospective study Omar k Jilani et al. assessed 73 patients with median age about 74 years. [6] There is no clear consensus in defining an elderly age group.

Generally, elderly patients are one whose general health condition influences the decision making in cancer care compared with younger [7]. In our study, we considered ≥ 60 years as per data published by the government of India in 2011 under the heading “Situation analysis of the elderly in India”, the cut-off age for defining the elderly is kept as 60 years [1]. Our study showed excellent tolerance of radical radiation treatment to older head and neck cancer patients with 95% (50) patients completing the treatment as opposed to 74.57% of patients completing the treatment in Vivek Tiwari et al. study [5]. The good number of patients completing the treatment in our study may be because only 25% of the patients were having associated comorbidity which may have contributed to the high rate of completion of treatment. Complete response at 6 weeks after treatment was 92.3%, which is a promising result. The uniqueness of our study is exclusion of post-operative cases to remove surgery as a confounding factor to assess the tolerance of radical radiotherapy, but included patient receiving concurrent chemotherapy. Analysis in response to radiotherapy depending on the subset did not show any significant differences, even though few studies showed poor prognosis or response of oropharynx and hypopharynx over larynx and nasopharynx and it also depends on other factors. In our study, the prominent sites were oropharynx (34.5%), hypopharynx (32.7%), and larynx (21.8%) as compared with the oral cavity (5.5%) and nasopharynx (5.5%); hence, the statistical significance could not be drawn with this much of the variation in the number of patients among the subsites. The stage of the disease is also a significant prognostic factor involved in treatment decision and outcome of the head and neck cancer patients. In our study, the common stage was stage IVA 41.8%, followed by stage III 32.7%, stage II 12.7%, stage IV B 9.1%, and stage I 3.6%, which is similar to the study where stages of the disease at diagnosis were similar between the elder and younger patients, stage I and II were 31.1% vs 29.8% and 37.9% vs 37% in stage III and 31% vs 33.2% stage IV disease, respectively [8]. Head and neck cancers commonly present in the advanced stage, especially in the oropharynx, nasopharynx, and hypopharynx over the larynx and oral cavity leading to hinder the response to treatment and survival outcomes [9]. Adding chemotherapy to radiotherapy increases acute toxicity even though it has shown benefit in local control and survival benefit. The survival benefits of adding chemotherapy to radiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck carcinoma is 4.5% at 1 year, which makes chemotherapy an important component in the treatment of advanced head and neck cancers, but shows reduced benefit after age 70 years [4].

The standard concurrent chemotherapy used in head and neck cancer is cisplatin or carboplatin. In our study, patient tolerated well to concurrent chemoradiation compared with radiotherapy alone, this is due to the good performance score of patients selected for chemotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone. However, the response remains similar for both. In our study, the patients who received a minimum of 200 mg/m2 cumulative dose was considered an adequate chemotherapy for cisplatin and 4 patients received non-cisplatin chemotherapy. Unlike other sites, radiation in head and neck cancer poses greater challenges in treatment because of the compact arrangement of critical structures, although there has been technological advancement in radiotherapy delivery, thus, reducing normal tissue toxicities. Toxicities in the head and neck region also associated with other factors like the technique of radiation. In our study, the majority of the patients (87.3%) underwent higher technology like IMRT, IGRT, and VMAT which helps in reducing toxicities in head and neck cancers. The severity of acute toxicities also depends on other factors like concurrent chemotherapy, stage, and nodal size [10]. The grades of acute toxicity in our study as per CTCAE v2.0 were grade II/III mucositis 54.5/40%, respectively, grade I/II dermatitis were 38.2/60% respectively; moderate and severe pain 80% and 10.9% respectively; and 9.1% of patients lost more than 11 kg, 38.2% of patients lost 6–10 kg, and 52.7% lost < 5 kg; and no grade IV toxicities were seen in our patients. This result shows less toxicity compared with a similar prospective study by Omar k Jilani which showed grade II/III acute toxicities in 96% of patients and grade IV toxicity was seen only by 4% [6]. Results in our study are because of the prophylactic nutritional supplement techniques and the use of higher technology. However, our study did not assess the late toxicities. We may assess late toxicities in the future. In a study which the outcomes of treatment among older and younger patient have been assessed showed an increase in toxicity, but an equal response to the treatment comparing both cohorts [11]. Completion of planned treatment in head and neck cancer is of paramount importance for better outcomes. Non-compliance to the treatment has been reported to be detrimental in disease control and survival [12]. Studies have shown delay or interruption of the treatment leading to an increase in overall treatment duration significantly decreasing the overall survival. Radiotherapy oncology prospective randomized trial between 1978 and 1991 reported a significant reduction in 3-year local control from 27 to 13% and 3-year absolute survival from 26 to 13% in patients with prolongation of treatment duration of 14 days or more [13]. Patel et al. showed that poor compliance to treatment resulted in a significantly higher risk of persistent neck disease in stage III/IV cancers [12]. In our study, the mean treatment duration was 46.67 days with 89.1% completing the treatment within 55 days, 3.6% of patients took more than 55 days due to an infection and acute toxicities. Our study did not show any significant interruption or prolongation of treatment between patient receiving radiotherapy alone vs concurrent chemoradiation but 8 patients stopped chemotherapy owing to acute toxicities, though they completed the planned radiotherapy. The supportive care during the head and neck cancer treatment is of utmost importance, in the head and neck cancers, compared with any other site because of functional impairment of critical structures which helps in swallowing, respiration, and speech. The acute toxicities like mucositis, pain, nausea, vomiting, and dysphagia will lead to significant interruption in the treatment or discontinuation of the treatment and morbidity during treatment. Nutritional support is an important part of head and neck cancer patients undergoing treatment, especially in elderly patients. Unfortunately, literature is limited, specifically, to nutrition during head and neck cancer treatment. In a study by Michal et al. which assessed the requirement of nutritional support comparing patients aged above 70 years with patient aged below 70 years undergoing chemoradiation showed 89% of patients among patients aged above 70 required feeding procedure compared with 69% of younger patients requiring feeding procedures [11]. And in an analysis of 5 cross-sectional studies of head and neck cancer patients, nutritional deficiency statistically correlated with age and symptoms [14]. There is controversy in using prophylactic feeding tubes for head and neck cancer patients: in one way, it helps to prevent significant weight loss and dehydration during treatment compared with therapeutic feeding tube and in another way, it will lead to feeding tube dependency by causing atrophy of swallowing functions after the treatment. But data is insufficient for conclusions [12]. However, the placement of feeding tubes during the treatment may be difficult and lead to increased overall treatment time. In our study, patients who had advanced disease and likely to have severe dysphagia underwent prophylactic PEG tube placement before the start of treatment to avoid unwanted weight loss, and delay in overall treatment time. This may be one of the reasons for patient’s compliance to the treatment in our study and mean weight loss of 5.44 kg with 9.1% [5] of patients losing weight more than 11 kg, 38.1% losing 6–11 kg and 52.7% losing less than 5 kg only.

Conclusion

Tolerance and response to radical chemoradiation for elderly head and neck cancer patients are good, and age should not be the only factor to refuse standard treatment. Close monitoring of patients with comorbidity is required, especially in the latter half of radiation to identify the toxicity for effective management.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr. Shiva Raj, N S statistician, Ramaiah Medical College, Bengaluru, for the statistics of the present work.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

A. S. Kirthi Koushik, Email: kirthi.koushik@gmail.com

K. S. Sandeep, Email: sandeepksrt15@gmail.com

M. G. Janaki, Email: drjanakimg@gmail.com

Ram Charith Alva, Email: drrcalva@gmail.com.

Irappa Vithoba Madabhavi, Email: irappamadabhavi@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Situation analysis of elderly in India | life expectancy | old age. (2011) Available from. https://www.scribd.com/document/102693341/Situation-Analysis-of-Elderly-in-India. Accessed 11 Jul 2019

- 2.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seiwert TY, EEW C. State-of-the-art management of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(8):1341–1348. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignon J-P, le Maître A, Maillard E, Bourhis J, MACH-NC Collaborative Group Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomized trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiwari V, Yogi V, Yadav S, Singh O, Ghori H, Peepre K (2015) Assessment of treatment tolerance and response of elderly head and neck cancer patients: a single-institution retrospective study. Clin Cancer Investig J 4:349–353

- 6.Jilani OK, Singh P, Wernicke AG, Kutler DI, Kuhel W, Christos P, et al. Radiation therapy is well tolerated and produces excellent control rates in elderly patients with locally advanced head and neck cancers. J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3(4):337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Socinski MA, Morris DE, Masters GA, Lilenbaum R. American College of Chest Physicians. Chemotherapeutic management of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):226S–243S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.226S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mountzios G. Optimal management of the elderly patient with head and neck cancer: issues regarding surgery, irradiation, and chemotherapy. World J Clin Oncol. 2015;6(1):7. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v6.i1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biazevic Maria Gabriela Haye, Antunes José Leopoldo Ferreira, Togni Janina, Andrade Fabiana Paula de, Carvalho Marcos Brasilino de, Wünsch-Filho Victor. Survival and quality of life of patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer at 1-year follow-up of tumor resection. Journal of Applied Oral Science. 2010;18(3):279–284. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572010000300015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.VanderWalde NA, Fleming M, Weiss J, Chera BS. Treatment of older patients with head and neck cancer: a review. Oncologist. 2013;18(5):568–578. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michal SA, Adelstein DJ, Rybicki LA, Rodriguez CP, Saxton JP, Wood BG, Scharpf J, Ives DI. Multi-agent, concurrent chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell cancer in the elderly. Head Neck. 2012;34(8):1147–1152. doi: 10.1002/hed.21891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel UA, Patadia MO, Holloway N, Rosen F. Poor radiotherapy compliance predicts persistent regional disease in advanced head/neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(3):528–533. doi: 10.1002/lary.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pajak TF, Laramore GE, Marcial VA, Fazekas JT, Cooper J, Rubin P, et al. Elapsed treatment days--a critical item in the radiotherapy quality control review in head and neck trials: RTOG report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;20(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90132-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy BA. Advances in quality of life and symptom management for head and neck cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2009;21(3):242–247. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32832a230c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]