Abstract

Background:

Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disease characterized by low bone density resulting in increased fracture susceptibility. This research was constructed to uncover the potential therapeutic application of osteoblasts transplantation, generated upon culturing male rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) in osteogenic medium (OM), OM containing gold (Au-NPs) or gold/hydroxyapatite (Au/HA-NPs) nanoparticles, in ovariectomized rats to counteract osteoporosis.

Methods:

Forty rats were randomized into: (1) negative control, (2) osteoporotic rats, whereas groups (3), (4) and (5) constituted osteoporotic rats treated with osteoblasts yielded from culturing BM-MSCs in OM, OM plus Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs, respectively. After 3 months, osterix (OSX), bone alkaline phosphatase (BALP), sclerostin (SOST) and bone sialoprotein (BSP) serum levels were assessed. In addition, gene expression levels of cathepsin K, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κb ligand (RANKL), osteoprotegerin (OPG) and RANKL/OPG ratio were evaluated using real-time PCR. Moreover, histological investigation of femur bone tissues in different groups was performed. The homing of implanted osteoblasts to the osteoporotic femur bone of rats was documented by Sex determining region Y gene detection in bone tissue.

Results:

Our results indicated that osteoblasts infusion significantly blunted serum BALP, BSP and SOST levels, while significantly elevated OSX level. Also, they brought about significant down-regulation in gene expression levels of cathepsin K, RANKL and RANKL/OPG ratio versus untreated osteoporotic rats. Additionally, osteoblasts nidation could restore bone histoarchitecture.

Conclusion:

These findings offer scientific evidence that transplanting osteoblasts in osteoporotic rats regains the homeostasis of the bone remodeling cycle, thus providing a promising treatment strategy for primary osteoporosis.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Osteoblasts, Gold, Hydroxyapatite, Bone remodeling

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a chronic skeletal ailment manifested by a rapid loss in bone mass which ultimately ends up with increased bone fragility with a high tendency to fracture. The major problem with osteoporosis is that it is an asymptomatic disorder until a bone fracture occurs, particularly, in the aged patients who once get one fracture; they become more susceptible to further fractures [1]. Thus, early diagnosis of osteoporosis is necessary to avoid the first fracture [2]. Osteoporosis is estimated to affect approximately 200 million women worldwide, with 8.9 million annual fracture incidents [3]. It is expected to globally affect about 14 million people above the age of 50 years by the end of 2020, resulting in an increased rate of bone fractures [4].

Fracture-associated osteoporosis is more prevalent in females above 55 years than males since it is affecting one out of every three women and 1 out of 12 men, leading to considerable unfavorable health outcomes [1, 5]. According to the latest International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) report, about 28.4% of postmenopausal Egyptian women are estimated to have osteoporosis, and Egyptian women have been found to have a rapid loss in bone mass relative to their western counterparts [6].

Bone fractures usually result in immobility and poor quality of life, especially hip fracture that is much related to high morbidity and mortality rate [7]. Major risk factors contributing to such disease are obesity, lack of physical activity, and inadequate calcium consumption [8].

The bone remodeling cycle is greatly based on the balance between bone formation and bone resorption via decay of the old bone matrix by osteoclasts and replacement and formation of a new one by osteoblasts [9]. Primary osteoporosis usually affects postmenopausal women due to estrogen deficiency. Since after menopause, estrogen shows declined levels, resulting in an imbalance in the bone remodeling process favoring bone resorption over formation [10]. Such imbalance leads to significant enhancement in osteoclastogenesis, which in turn yields extensive bone loss [11]. The current therapies for osteoporosis either target resorptive events, such as bisphosphonates, strontium ranelate, calcitonin, and the selective estrogen-receptor modulator or anabolic events such as parathyroid hormone fragments and sclerostin inhibitors [12]. However, such treatment modalities fail to overcome the resulting structural damage, and they only aim to mitigate the intensity of bone remodeling events and the risk of further fractures, in addition to having certain restrictions regarding their efficacy and long-term safety [13]. Hence, there is a pressing need to introduce an effective approach with promising therapeutic possessions and low side effects for the treatment of osteoporosis.

Bone regeneration through mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) infusion has been found to induce osteogenesis, thus offering a rational therapeutic opportunity for the treatment of primary osteoporosis [14]. Stem cell implantation in both animals and humans has been extensively used for treating many diseases. However, systemic transplantation of MSCs in vivo has failed to stimulate an osteogenic response in bone owing to the failure of MSCs to migrate to the bone surface unless they were genetically manipulated or recruited after certain injuries. Even if the infused MSCs are targeted to the bone, they are usually found to engraft in the upper metaphysic, epiphysis, or within the bone marrow sinusoids, besides the issue of the short-term engraftment [15]. To overcome this obstacle in using MSCs for bone regeneration, this study was established to unearth the possible implementation of the systemic infusion of osteoblasts derived from male rat BM-MSCs co-cultured with osteogenic medium (OM) alone or combined with either gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) or gold/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite (Au/HA-NPs) in repairing bone deterioration in an experimental model of primary osteoporosis.

Materials and methods

In vitro osteoblasts generation

The protocols involved in in vitro osteoblasts generation and characterization are described in our previous research [16]. In brief, male rat BM-MSCs cultures of 3rd passage were differentiated into osteoblasts through culturing in osteogenic differentiation medium (OM), containing 5.0 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid and 0.1 μM dexamethasone [17] or OM supplemented with either gold (Au-NPs) or gold/hydroxyapatite (Au/HA-NPs) for 14 days. The identity of the generated osteoblasts was confirmed by estimating the osteoblast-specific genes [Runt-related transcription factor-2 (Runx-2) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2)] expression levels using real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and detecting the bone matrix mineralization using alizarin red S assay.

In vivo study

Animals

Forty adult female albino rats of Wistar strain (150–180 g) were procured from the Central Animal House Facility of the National Research Centre, Giza, Egypt. The rats were allocated in clean cages in an environmentally controlled area of 25 ± 1 °C temperature, alternating day/night cycle and humidity of (55–60) %. The rats were left for adaptation with such conditions for two weeks before initiating the experiment with free access to tap water and standard rodent pellets (Wadi El-Kabda Co., Cairo, Egypt).

Model creation and cell transplantation

After the acclimatization period, the rats were randomized into five groups (8 rats/group), one group was referred as the sham group that was subjected to sham surgery in which only the periovarian fat pads were removed while keeping both ovaries intact, and was intravenously injected with a single dose of sterile saline, 3 months after the surgery. The other four groups were surgically ovariectomized under anesthesia at Hormones Department, Medical Research Division, National Research Centre, Egypt and then left for 3 months to induce experimental primary osteoporosis [18]. Then, these groups were assigned as osteoporotic group that was left untreated but intravenously injected via tail vein with a single dose of saline, OM group which was intravenously injected via tail vein with a single dose of osteoblasts (suspended in PBS) generated from in vitro culturing of male rat BM-MSCs in osteogenic medium (3 × 106 cells/rat), Au-NPs group which was intravenously injected with a single dose of osteoblasts generated from in vitro culturing of male rat BM-MSCs in OM supplemented with Au-NPs (3 × 106 cells/rat) and Au/HA-NPs group which was intravenously injected with a single dose of osteoblasts generated from in vitro culturing of male rat BM-MSCs in OM supplemented with Au/HA-NPs (3 × 106 cells/rat) [19]. All groups were left for three months.

After the treatment period was over, all rats were permitted to fast overnight and then the blood samples were withdrawn from the retro-orbital venous plexus under anesthesia. The serum was obtained by centrifugation of the blood samples at 1800 xg for 10 min at 4 °C using a cooling centrifuge (Sigma 2 K-15, Osterode, Germany) for further biochemical determinations. After blood collection, the animals were rapidly sacrificed and the right femur bones of rats were excised, cleaned from any attached muscles, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at –80 °C for later molecular analysis. While left femur bones of rats were carefully cleaned and preserved in formal saline (10%) for the histological examination.

Biochemical assays

Serum osterix (OSX) (Cat. # KN0994Ra), and bone alkaline phosphatase (BALP) (Cat. # KN0818Ra), sclerostin (SOST) (Cat. # KN0995Ra) and bone sialoprotein (BSP) (Cat. # KN0993Ra) levels were estimated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using kits supplied from Kono Biotech Co., Ltd (Zhejiang, China) under the guidance of the producer.

Molecular genetics analysis

Quantitative gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the femur bone tissue of rats in each group using the method of trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, Cat. #15596-018) combined with RNeasy mini kit for total RNA purification from animal cells (Cat. #74104, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instruction. The RNA quantity and quality were assessed by the aid of NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) using ratio. Then, RNA aliquots were pre-treated with DNase I, RNase-free (1U/μl) (Cat. # EN0521, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA). After that, complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using Revert Aid first strand cDNA synthesis kit (Cat. # K1621, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Lithuania) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Cat. # 204141, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was employed to perform quantitative gene expression analysis of (cathepsin K, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κb ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin (OPG)) in the bone tissues using StepOne Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s manual. 10X Quantitect Primer Assays (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) were used for all target genes: cathepsin K (Cat. # QT00375599), RANKL (Cat. # QT00195125) and OPG (Cat. # QT00177170). β-actin (Cat. # QT00193473) was used as an endogenous control. Relative mRNA expression with respect to corresponding control value was quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt comparative method after normalization with β-actin gene [20].

Data were represented as the fold change in the gene expression level in the osteoporotic group as compared to the sham group. While for all osteoblasts-infused groups, data were expressed as the fold change in the gene expression relative to the untreated osteoporotic group.

PCR detection of the sex-determining region on the Y chromosome in femur bones of the treated female rats

Sex determining region on the Y chromosome (SRY) gene of the injected osteoblasts derived from the male rat BM-MSCs was detected by PCR to assure the accommodation of injected osteoblasts (resulted from in vitro culturing male rat BM-MSCs in OM either alone or combined with Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs) to the femur bones of the recipient female rats. Male rat genomic DNA (as a positive control) and female rat genomic DNA (as a negative control) were included in each run. In brief, frozen femur bones of female rats in different groups were ground using mortar and pestle by the aid of liquid nitrogen, followed by the extraction of the genomic DNA using QIAamb DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany. Cat. # 51304), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality and concentration were evaluated using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) at 260 nm and 280 nm wavelength. The subsequent conventional PCR was performed using 100 ng of DNA in a final volume of 20 μl containing 10X Dream Taq green PCR buffer (pH 8.8) (Cat. # EP0712), 10 mM dNTPs mix (Cat. # R0241), 5 U/μl of Dream Taq DNA polymerase (Cat. # EP0712), and 10 μM of each of forward and reverse SRY primer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR cycles were carried out using a gradient thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with the following steps; 5 min initial denaturation at 94 °C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30s, annealing at 66 °C for 30s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min and then one cycle of a final extension at 72 °C for 8 min.

Primer sequence for SRY (Genbank accession no. NC_024475) was designed manually using DNASTAR Lasergene 7.1 SeqBuilder software producing PCR product of 118 bp size. The sequence of forward and reverse primers for SRY gene is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

SRY gene primer sequences used for conventional PCR

| SRY primer | Sequence | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Forward | 5′-CTCAACAGAATCCCAGCATG-3′ | (71–90) |

| Reverse | 5′-GTCTTC AGTCTCTGCGCCT-3′ | (170–188) |

Histological examination

After fixation of the rat femur bones in 10% formal saline for 24 h, they were decalcified by formic acid solution (10%), dehydrated by a series of alcohols of different grades, followed by being embedded in molten paraffin bee wax at 56 °C for 24 h. Paraffin tissue blocks were cut into slices of 4 µm thick by rotary microtome, deparaffinized and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological investigation under the electric light microscope (Olympus BX51 microscope, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan) [21].

Statistics

The attained results are delineated as means ± standard deviations (S.D). Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) program, version 17, followed by the least significant difference (LSD) to compare the significance between groups. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Percent of change, indicating the percentage of the difference relative to the corresponding control group, was also calculated using this formula:

Results

Bone turnover markers monitoring

Table 2 points to the influence of treatment with osteoblasts (generated from in vitro culturing of BM-MSCs in OM either alone or in combination with Au-NPs or Au-HA-nanocomposite) on the serum levels of bone turnover indices (OSX, BALP, SOST, and BSP) in the osteoporotic rats. The osteoporotic rats elicited a significant elevation (p < 0.05) in the serum BALP, SOST and BSP levels with a percent change of 33.13%, 328.07%, and 99.35%, respectively, in concomitant with a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in serum OSX level (–61.03%) versus the sham group. On the opposite side, treatment of osteoporotic groups with osteoblasts (derived from BM-MSCs differentiation by either OM alone or supplemented with Au-NPs or Au/HA-nanocomposite) yielded a significant rise (p < 0.05) in serum OSX level by 126.6%, 146.4%, and 134.66%, respectively, when compared with the osteoporotic group.

Table 2.

The outcomes of treatment with osteoblasts on bone turnover markers’ level in primary osteoporosis rat model

| Group | Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSX (pg/ml) | BALP (ng/ml) | SOST (pg/ml) | BSP (pg/ml) | |

| Sham | 481.2 ± 20.72 | 50.70 ± 3.86 | 130.00 ± 41.07 | 218.20 ± 12.31 |

| Osteoporotic |

187.5 ± 124.37a,b (− 61.03%) |

67.50 ± 11.45a (33.13%) |

556.50 ± 71.53a (328.07 %) |

435.00 ± 124.37a (99.35%) |

| OM |

425.0 ± 25.00b (126.6 %) |

55.00 ± 8.10b (–18.51%) |

520.00±90.82a (− 6.55%) |

377.00 ± 95.95a (–13.33%) |

| Au-NPs |

462.0 ± 92.03b (146.4%) |

47.10 ± 2.65b (–30.22%) |

191.86±27.01b,c (− 65.52%) |

233.20 ± 33.78b,c (– 46.39%) |

| Au/HA-NPs |

440.0 ± 22.36b (134.66%) |

58.00±11.51 (–14.07%) |

422.00±98.33a,b,c,d (− 24.16 %) |

290.00 ± 72.02b,c (– 33.33%) |

Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.)

aSignificant change at p < 0.05 versus the sham group

bSignificant change at p < 0.05 versus the osteoporotic group

cSignificant change at p < 0.05 versus the OM group

dSignificant change at p < 0.05 versus the Au-NPs group

(%): Percentage change versus the corresponding control value

Regarding SOST and BSP serum levels, significant decline (p < 0.05) was noticed in the osteoporotic groups infused with osteoblasts (derived from BM-MSCs differentiation in OM supplemented with either Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs) by – 65.52% and – 46.39%, respectively, for Au-NPs and by − 24.16% and − 33.33%, respectively, for Au/HA-NPs, relative to the osteoporotic group, while the infusion of osteoblasts resulted from in vitro culture in OM alone exhibited insignificant blunting (p > 0.05) in serum SOST and BSP levels with a percent change of − 6.55% and − 13.33%, respectively, with respect to those of the osteoporotic group. Injection of the osteoporotic group with the generated osteoblasts (either through the culturing with OM alone or combined with Au-NPs) displayed significant drop (p < 0.05) in serum BALP level with a percent change of − 18.51% and − 30.22%, respectively, relative to the osteoporotic group. Meanwhile, injection with osteoblasts, resulted from culturing of BM-MSCs with Au/HA-NPs combined with OM, brought about an insignificant diminution (p > 0.05) in the serum level of BALP (− 14.07%) compared to the osteoporotic group.

Of note, the Au-NPs group revealed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the serum level of SOST when compared with both OM and Au/HA-NPs groups and a significant diminution (p < 0.05) in the BSP serum level relative to the OM group. Also, the Au/HA-NPs group showed a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in the serum levels of SOST and BSP as compared to the OM group. These findings denoted that Au-NPs followed by Au/HA-NPs group exerted the most modulating effect on the bone resorption markers. From another point of view, Au-NPs group showed a reduced serum level of BALP, but this decline was not significantly different when compared to both Au/HA-NPs and OM groups and exhibited an elevated OSX serum level, but such elevation was not statistically different compared with Au/HA-NPs and OM groups. These data suggested that all osteoblast-infused groups had similar influence regarding the bone formation markers.

Molecular genetics outcomes

Quantitative gene expression analysis

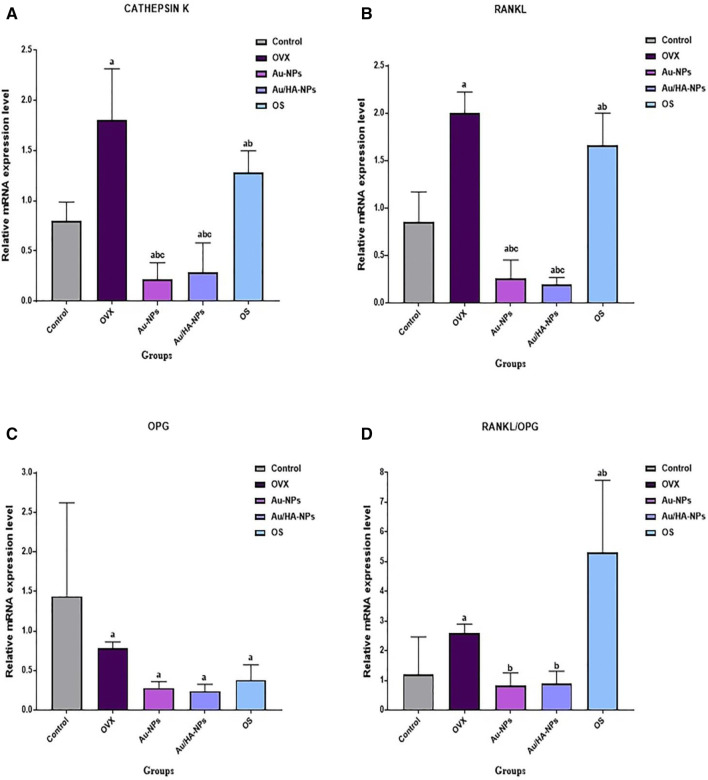

Figure 1 illustrates the influence of osteoblasts infusion, resulted from in vitro culturing of BM-MSCs in OM either alone or combined with Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs, on the expression pattern of cathepsin K, RANKL, OPG, and RANKL/OPG ratio in the osteoporotic rat model. Osteoporotic rats exhibited a significant amplification (p < 0.05) of cathepsin K and RANKL gene expression levels as compared to the sham group. On the other side, this group showed a significant down-regulation (p < 0.05) of OPG gene expression level relative to the sham group, leading to significant enhancement (p < 0.05) in the overall ratio of RANKL/OPG versus the sham group. On the other hand, all osteoblast-treated groups (OM, Au-NPs and Au/HA-NPs groups) experienced a significant down-regulation (p < 0.05) in the expression patterns of cathepsin K and RANKL genes when compared to the osteoporotic group. Surprisingly, the treatment with osteoblasts, resulted from in vitro differentiation of BM-MSCs in OM either alone or supplemented with Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs, resulted in an insignificant change (p > 0.05) in OPG gene expression level as compared with the osteoporotic group. However, all osteoblasts-treated groups produced an overall significant decline (p < 0.05) in the RANKL/OPG ratio with respect to the osteoporotic group.

Fig. 1.

Quantitative gene expression patterns of A cathepsin K, B RANKL, C OPG and D RANKL/OPG ratio in the bone tissue of different experimental groups. Data are expressed as Mean ± S.D. a: Significant change at p < 0.05 in comparison with the Sham group, b: Significant change at p < 0.05 in comparison with the osteoporotic group, c: Significant change at p < 0.05 in comparison with OM group

Noteworthy, both Au-NPs and Au/HA-NPs groups presented a significant down-regulation (p < 0.05) in the gene expression levels of cathepsin K, RANKL, and RANKL/OPG ratio when compared with the OM group. However, there is an insignificant difference (p > 0.05) between Au-NPs and Au/HA-NPs group regarding their effect on the gene expression levels of cathepsin K, RANKL and RANKL/OPG ratio, which suggests that both groups are equally effective in down-regulating the transcript levels of these genes.

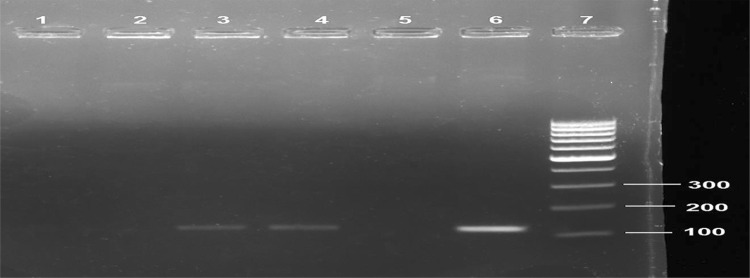

SRY gene detection in the femur bones of osteoporotic female rats

Figure 2 illustrates the expression of the SRY gene in the femur bones of female recipients in the different groups. Femur bones obtained from the osteoporotic rats showed negative expression of the SRY gene (lane 1). While that of osteoporotic rats treated with osteoblasts (derived from BM-MSCs culturing in OM alone) displayed no expression of the SRY gene (lane 2). Interestingly, the SRY gene was only detected in the femur bones from Au-NPs and Au/HA-NPs groups (lanes 3 and 4), respectively. These findings document the successful homing of the male donor osteoblasts to the injured femur bones of the female recipients from Au-NPs and Au/HA-NPs groups.

Fig. 2.

Representative agarose gel image displaying SRY gene expression in the femur bones of different groups by conventional PCR. SRY gene amplicon size is 118 bp. Osteoporotic group (lane 1), OM group (lane2), Au-NPs group (lane 3), Au/HA-NPs group (lane 4), negative control female rats (lane 5), positive control male rat (lane 6), and 100 bp DNA ladder (lane 7)

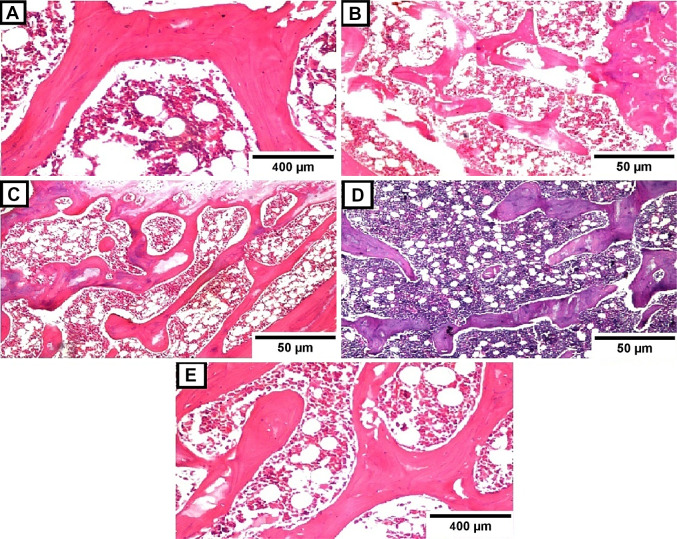

Histological observations

Figure 3 shows the histological features of the bone tissue section stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) from the different studied experimental groups. The optical micrograph of a femur bone tissue section of rat in the sham group displayed normal histoarchitecture of the bone trabeculae with osteoblasts arranged in groups in the Haversian system with bone marrow cells in between (Fig. 3A). On the contrary, the microscopic observation of a femur bone tissue section of the osteoporotic rat exhibited severe bone resorption in the smaller-sized bone trabeculae, indicating osteoporosis induction in this group (Fig. 3B). While the histological examination of the femur bone tissue section obtained from rats in the OM group denoted mild bone resorption in some bone trabeculae (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Transverse sections through the bone tissues stained with hematoxylin & eosin (H&E). Bone tissue sections obtained from: A Sham group (H&E, × 40); B Osteoporotic group (H&E, × 16); C OM group (H&E, × 16); D Au-NPs group (H&E, × 16) and E Au/HA-NPs group (H&E, × 40)

Interestingly, photomicrographs of femur bone tissue sections of osteoporotic rats infused with osteoblasts generated from BM-MSCs cultured in OM supplemented with either Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs revealed no histopathological change in the articular cartilaginous surface with a normal size bone trabeculae and intact bone marrow in addition to calcium deposition in the Haversian system (Fig. 3D, E, respectively).

Discussion

With increasing the aging sector in the population in most countries, bone disorders have become a critical health burden, resulting in increased risk for bone fractures. Therefore, the need for effective diagnostic tools to be utilized in the screening and follow-up of such diseases has strikingly increased. Biochemical indices, in addition to imaging techniques, have been shown to be essential for assessment and diagnosis of metabolic bone disorders, especially osteoporosis, since they represent relatively inexpensive non-invasive diagnostic tools [22].

On the experimental level, ovariectomy is regarded as the most attractive procedure to identify the pathological mechanism of postmenopausal events for developing new therapeutic approaches in order to manage postmenopausal osteoporosis [23]. Ovariectomized rat models were found to go through the same phenomena of the bone remodeling process just like those happening in postmenopausal osteoporosis as a result of estrogen deficiency in females. Moreover, the rat model attains osteoporosis within a short period (3 months) as compared to rabbits (6 months) which makes them an interesting model for this procedure [24].

In the current study, the ovariectomized group revealed a significant drop in serum OSX level, which is greatly supported by the study of Zhou et al. [25], also it showed a significant elevation in the serum levels of BALP, SOST, and BSP, as opposed to the sham-operated group. The latter findings are in harmony with the study of Abuohashish and Co-workers [26], Kim et al. [27], Shaarawy and Hasan [28], respectively. Moreover, the current outcomes indicated a significant up-regulation of the RANKL gene expression level in concomitant with a significant down-regulation of the OPG gene expression level, leading to an overall significant enhancement of RANKL/OPG ratio in the bone tissue of the ovariectomized group versus the sham-operated group. Such findings fit those of Li et al. [29]. Ultimately, the ovariectomized group displayed a significant over-expression of the cathepsin K gene in comparison with the sham-operated group, which greatly coincides with the finding of Govindarajan et al. [30].

The above-mentioned findings could be attributed to the estrogen deficiency associated with ovariectomy, resulting in promoting the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [31], which is responsible for repressing OSX expression [32] and inducing SOST over-expression through increasing the transcriptional activity of myocyte enhancer factors 2 (MEF2) [27]. Also, the elevated level of TNF-α could increase RANKL and cathepsin K mRNA expression, while decreasing OPG mRNA expression [33, 34]. Furthermore, estrogen decline, following ovariectomy, is responsible for stimulating the osteoclastic bone resorption and matrix degradation and hence increases the secretion of BALP in the blood, resulting in the observed increase in its level [26]. Additionally, estrogen deficiency reduces the transcriptional activity of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) [35], leading to the observed elevation in the serum BSP level. Since ERα silencing in human MSCs during the osteoblastogenesis has been reported to yield a significant up-regulation in BSP gene expression level [36].

The osteoblast is a bone-forming cell derived from MSCs through various regulatory transcription factors, such as BMP and Wnt pathways [37]. The current study denoted the successful homing of sex-mismatched osteoblasts (derived from male rat BM-MSCs incubated in OM supplemented with either Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs), after intravenous infusion, to the site of injured femur bones of ovariectomized female rats. Their homing was documented by the detection of the SRY gene in the female’s femur bone tissue as evidenced by PCR. However, SRY gene was not detected in the bone tissue of ovariectomized rats treated with osteoblasts derived from BM-MSCs incubated in OM alone. This could be ascribed to the synergistic effect of the studied nanostructures with OM on the in vitro osteogenic differentiation of BM-MSCs for inducing bone formation in vivo. These results are in agreement with those reported by Song et al. [38] who observed the homing of male dog derived BM-MSCs in the bone cavities of female recipients through the detection of the SRY gene. Okabe and his colleagues [39] confirmed the safety of osteoblast infusion since almost all cells were cleared toward the site of the defect without any inclusion within any other non-target organs and with no histopathological alterations. However, the mechanism underlying the migration of implanted osteoblasts from blood circulation to the femur bone of osteoporotic female rats, to participate in the bone formation process, has not yet been clearly specified and needs further investigation.

In the present work, the cultured osteoblasts infusion in the ovariectomized rats, resulted from in vitro differentiation of BM-MSCs either in OM alone or in combination with Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs, elicited a significant increment in the serum level of OSX in association with a remarkable decline in BALP, BSP and SOST serum levels as compared to the ovariectomized rats. In addition, significant down-regulation of both RANKL and cathepsin K gene expression levels and a decreased RANKL/OPG ratio were detected in the osteoblast-treated groups versus the ovariectomized group. A study of Liu et al. [40] demonstrated that MSCs transplantation mitigates joint damage and osteoporosis through improving the impaired osteogenic differentiation ability of MSCs in arthritic mice through the suppression of TNF-α, which leads to the significant up-regulation of osteogenic genes, including Runx-2 and OSX. In support of the other studies [41, 42], our study suggests that BMP signaling activation, following osteoblast injection, may be responsible for the transcriptional activation of osteogenic genes, such as OSX. Also, the decline in TNF-α production, as a result of osteoblast transplantation, promotes the inhibition of bone resorption and osteoclastogenesis [43, 44], leading to the reduction of bone turnover markers; BALP, BSP, and SOST. The present study also hypothesizes that such a drop in these markers could be ascribed to the Wnt pathway activation, following the osteoblast infusion in the osteoporotic rats, which is known to inhibit osteoclastogenesis events via reducing the transcriptional level of RANKL, affecting the overall RANKL/OPG ratio [45]. Of note, the decreased gene expression level of RANKL contributes to the down-regulation of cathepsin K gene expression level via suppressing the nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 1 (NFATC1) activity [30].

Unexpectedly, OPG gene expression level revealed insignificant changes in all treated groups (OM, Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs) when compared with the ovariectomized group, suggesting the role of implanted osteoblasts in modulating the osteoclastogenesis, hence, alleviating bone resorption rather than contributing to the bone formation process. The study of Pramusita et al. [46] revealed that the treatment of osteoblasts, derived from rat BM-MSCs, with melatonin, causes a diminished RANKL level and insignificantly changes OPG level as compared to the control, resulting in the overall decline in the RANKL/OPG ratio.

Histological investigation of a femur bone tissue section of the ovariectomized rat revealed bone resorption in the small-sized bone trabeculae. This observation goes hand by hand with the study of Abuohashish et al. [26]. This is certainly attributed to the estrogen deficiency responsible for bone resorption and osteoporosis [47]. The optical micrograph of a femur bone tissue section from the rats infused with osteoblasts, derived from incubation of BM-MSCs in OM alone, revealed mild trabecular bone resorption that could be owing to the inability of implanted osteoblasts to home to the site of the bone defect as confirmed by SRY gene analysis. However, photomicrographs of the femur bone tissue sections of the ovariectomized rats infused with the cultured osteoblasts (Au-NPs and Au/HA-NPs groups) revealed a marked resolution of the histological architecture of the osteoporotic femur bones. This finding is in accordance with that of Sadat-Ali et al. [48], who commented that the intravenous infusion of BM-MSCs-derived osteoblasts in the ovariectomized rats supports the bone formation in the injured distal femur and lumbar spine, and augments the thickness of the trabeculae, suggesting that such desirable effect could be due to the homing of the injected osteoblasts to the site of bone surface rather any other tissues.

Conclusively, the outcomes of the current attempt emphasize the synergistic effect of OM with nanostructures (Au-NPs or Au/HA-NPs) in motivating the osteogenic differentiation of BM-MSCs. Moreover, this investigation denoted that intravenous delivery of osteoblasts in the osteoporotic rat model affords bone repair via retaining bone remodeling cycle. Hence, the generated osteoblasts in the present study could establish a fruitful base for the configuration of cell-based therapy in osteoporosis which needs to be translated to the clinical milieu.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully appreciate the financial support of the National Research Centre, Egypt (Thesis fund no. 71511). Also, the authors express sincere appreciation to Prof. Adel Bakeer Kholousy, Professor of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University for his kind participation in histological examination of this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no financial conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

This study was conducted according to the ethical considerations for the experimental animals and approved by the Ethical Committee for Medical Research of the National Research Centre, Giza, Egypt, which follows the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Approval No.15106).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Compston JE, McClung MR, Leslie WD. Osteoporosis. Lancet. 2019;393:364–376. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akkawi I, Zmerly H. Osteoporosis: current Concepts. Joints. 2018;6:122–127. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1660790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Tawab SS, Sabs EK, Elweshahi HM, Ashry MH. Knowledge of osteoporosis among women in Alexandria (Egypt): a community based survey. Egypt Rheumatol. 2015;38:225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobeih HS, Abd Elwahed AT. Knowledge and perception of women at risk for osteoporosis: educational intervention. Egypt Nurs J. 2018;15:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrawal VK, Gupta DK. Recent update on osteoporosis. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2013;2:164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hossien YE, Tork HMM, El-Sabeely AA. Osteoporosis knowledge among female adolescents in Egypt. Am J NursSci. 2014;3:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sözen T, Özışık L, Başaran NÇ. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017;4:46–56. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin X, Xiong D, Peng YQ, Sheng ZF, Wu XY, Wu XP, et al. Epidemiology and management of osteoporosis in the people’s republic of china: current perspectives. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1017–1033. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S54613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pino AM, Rosen CJ, Rodríguez JP. In osteoporosis, differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) improves bone marrow adipogenesis. Biol Res. 2012;45:279–287. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602012000300009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji MX, Yu Q. Primary osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2015;1:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng X, McDonald JM. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:121–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luhmann T, Germershaus O, Groll J, Meinel L. Bone targeting for the treatment of osteoporosis. J Control Release. 2012;161:198–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kular J, Tickner J, Chim SM, Xu J. An overview of the regulation of bone remodeling at the cellular level. Clin Biochem. 2012;45:863–873. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez JR, Kouroupis D, Li DJ, Best TM, Kaplan L, Correa D. Tissue engineering and cell-based therapies for fractures and bone defects. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2018;6:105. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao W, Lane NE. Target delivery of mesenchymal stem cells to bone. Bone. 2015;70:62–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahmoud S, Ahmed HH, Mohamed MR, Amr KS, Aglan HA, Ali MAM, et al. Role of nanoparticles in osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotechnology. 2020;72:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10616-019-00353-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yi C, Liu D, Fong CC, Zhang J, Yang M. Gold nanoparticles promote osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells through p38 MAPK pathway. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6439–6448. doi: 10.1021/nn101373r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Power RA, Iwaniec UT, Magee KA, Mitova-Caneva NG, Wronski TJ. Basic fibroblast growth factor has rapid bone anabolic effects in ovariectomized rats. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:716–723. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed HH, Mahdy EE, Shousha WG, Rashed LA, Abdo SM. Potential role of bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells with or without injectable calcium phosphate composite in management of osteoporosis in rat model. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;5:494–504. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 (-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banchroft JD, Stevens A, Turner DR. Theory and practice of histological techniques. 4. New York: Churchil Livingstone; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seibel MJ. Clinical application of biochemical markers of bone turnover. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2006;50:603–620. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302006000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sophocleous A, Idris AI. Rodent models of osteoporosis. Bonekey Rep. 2014;3:614. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2014.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Goh J, Das De S, Ge Z, Ouyang H, Chong JS, et al. Efficacy of bone marrow-derived stem cells in strengthening osteoporotic bone in a rabbit model. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1753–1761. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou W, Liu Y, Shen J, Yu B, Bai J, Lin J, et al. Melatonin increases bone mass around the prostheses of ovx rats by ameliorating mitochondrial oxidative stress via the SIRT3/SOD2 signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:4019619. doi: 10.1155/2019/4019619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abuohashish HM, Ahmed MM, Al-Rejaie SS, Eltahir KE. The antidepressant bupropion exerts alleviating properties in an ovariectomized osteoporotic rat model. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36:209–220. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim BJ, Bae SJ, Lee SY, Lee YS, Baek JE, Park SY, et al. TNF-α mediates the stimulation of sclerostin expression in an estrogen-deficient condition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;424:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaarawy M, Hasan M. Serum bone sialoprotein: a marker of bone resorption in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2001;61:513–522. doi: 10.1080/003655101753218274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li CW, Liang B, Shi XL, Wang H. OPG/RANKL mRNA dynamic expression in the bone tissue of ovariectomized rats with osteoporosis. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:9215–9224. doi: 10.4238/2015.August.10.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Govindarajan P, Böcker W, El Khassawna T, Kampschulte M, Schlewitz G, Huerter B, et al. Bone matrix, cellularity, and structural changes in a rat model with high-turnover osteoporosis induced by combined ovariectomy and a multiple-deficient diet. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:765–777. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfeilschifter J, Köditz R, Pfohl M, Schatz H. Changes in proinflammatory cytokine activity after menopause. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:90–119. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu X, Beck GR, Jr, Gilbert LC, Camalier CE, Bateman NW, Hood BL, et al. Identification of the homeobox protein Prx1 (MHox, Prrx-1) as a regulator of osterix expression and mediator of tumor necrosis factor alpha action in osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:209–219. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamdy NA. Targeting the RANK/RANKL/OPG signaling pathway: a novel approach in the management of osteoporosis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;8:299–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa AG, Cusano NE, Silva BC, Cremers S, Bilezikian JP. Cathepsin K: its skeletal actions and role as a therapeutic target in osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:447–456. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armstrong VJ, Muzylak M, Sunters A, Zaman G, Saxon LK, Price JS, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a component of osteoblastic bone cell early responses to load-bearing and requires estrogen receptor alpha. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20715–20727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delhon I, Gutzwiller S, Morvan F, Rangwala S, Wyder L, Evans G, et al. Absence of estrogen receptor-related-α increases osteoblastic differentiation and cancellous bone mineral density. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4463–4472. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katsimbri P. The biology of normal bone remodeling. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017;26:e12740. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song G, Habibovic P, Bao C, Hua J, van Blitterswijk CA, Yuan H, et al. The homing of bone marrow MSCs to non-osseous sites for ectopic bone formation induced by osteoinductive calcium phosphate. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2167–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okabe YT, Kondo T, Mishima K, Hayase Y, Kato K, Mizuno M, et al. Biodistribution of locally or systemically transplanted osteoblast-like cells. Bone Joint Res. 2014;3:76–81. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.33.2000257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu C, Zhang H, Tang X, Feng R, Yao G, Chen W, et al. mesenchymal stem cells promote the osteogenesis in collagen-induced arthritic mice through the inhibition of TNF-α. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:4069032. doi: 10.1155/2018/4069032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leong WF, Zhou T, Lim GL, Li B. protein palmitoylation regulates osteoblast differentiation through bmp-induced osterix expression. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rahman MS, Akhtar N, Jamil HM, Banik RS, Asaduzzaman SM. TGF-β/BMP signaling and other molecular events: regulation of osteoblastogenesis and bone formation. Bone Res. 2015;3:15005. doi: 10.1038/boneres.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lam J, Takeshita S, Barker JE, Kanagawa O, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL. TNF-alpha induces osteoclastogenesis by direct stimulation of macrophages exposed to permissive levels of RANK ligand. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1481–1488. doi: 10.1172/JCI11176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao B, Grimes SN, Li S, Hu X, Ivashkiv LB. TNF-induced osteoclastogenesis and inflammatory bone resorption are inhibited by transcription factor RBP-J. J Exp Med. 2012;209:319–334. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobayashi Y, Maeda K, Takahashi N. Roles of Wnt signaling in bone formation and resorption. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2008;44:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pramusita A, Mastutik G, Putra ST. Role of melatonin in down-regulation of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand: osteoprotegerin ratio in rat—bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cells. JKIMSU. 2018;7:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davidge ST, Zhang Y, Stewart KG. A comparison of ovariectomy models for estrogen studies. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R904–R907. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.3.R904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sadat-Ali M, Al-Turki HA, Acharya S, Al-Dakheel DA. Bone marrow-derived osteoblasts in the management of ovariectomy induced osteoporosis in rats. J Stem Cells Regen Med. 2018;14:63–68. doi: 10.46582/jsrm.1402010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]