Abstract

Background

The Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System (ESSQS) was introduced in Japan to improve the quality of laparoscopic surgery. This cohort study investigated the short‐ and long‐term postoperative outcomes of colorectal cancer laparoscopic procedures performed by or with qualified surgeons compared with outcomes for unqualified surgeons.

Methods

All laparoscopic colorectal resections performed from 2010 to 2013 in 11 Japanese hospitals were reviewed retrospectively. The procedures were categorized as performed by surgeons with or without the ESSQS qualification and patients' clinical, pathological and surgical features were used to match subgroups using propensity scoring. Outcome measures included postoperative and long‐term results.

Results

Overall, 1428 procedures were analysed; 586 procedures were performed with ESSQS‐qualified surgeons and 842 were done by ESSQS‐unqualified surgeons. Upon matching, two cohorts of 426 patients were selected for comparison of short‐term results. A prevalence of rectal resection (50·3 versus 40·5 per cent; P < 0·001) and shorter duration of surgery (230 versus 238 min; P = 0·045) was reported for the ESSQS group. Intraoperative and postoperative complication and reoperation rates were significantly lower in the ESSQS group than in the non‐ESSQS group (1·2 versus 3·6 per cent, P = 0·014; 4·6 versus 7·5 per cent, P = 0·025; 1·9 versus 3·9 per cent, P = 0·023, respectively). These findings were confirmed after propensity score matching. Cox regression analysis found that non‐attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons (hazard ratio 12·30, 95 per cent c.i. 1·28 to 119·10; P = 0·038) was independently associated with local recurrence in patients with stage II disease.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic colorectal procedures performed with ESSQS‐qualified surgeons showed improved postoperative results. Further studies are needed to investigate the impact of the qualification on long‐term oncological outcomes.

The outcomes of 586 procedures performed or attended by surgeons certified by the Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System (ESSQS) were compared with 842 procedures performed by surgeons without the ESSQS qualification. Attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons led to superior outcomes in terms of duration of surgery, and operative complication and reoperation rates. Non‐attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons was independently associated with local recurrence in patients with stage II disease.

Qualification and outcomes in colorectal surgery

Antecedentes

El Sistema de Certificación de Habilidades Quirúrgicas Endoscópicas (Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System, ESSQS) fue introducido en Japón para mejorar la calidad de la cirugía laparoscópica. En este estudio de cohortes se investigaron los resultados postoperatorios a corto y a largo plazo de las intervenciones laparoscópicas de cáncer colorrectal realizadas por o con la asistencia de cirujanos con certificación en comparación con cirujanos no certificados.

Métodos

Todas las resecciones colorrectales laparoscópicas realizadas entre 2010 y 2013 en 11 hospitales japoneses fueron revisadas retrospectivamente. Los procedimientos se clasificaron en función de si habían sido realizados por cirujanos con o sin certificación del ESSQS, y las características clínicas, patológicas y quirúrgicas de los pacientes se utilizaron para emparejar los subgrupos mediante puntuaciones de propensión. Las variables de resultado incluyeron los resultados postoperatorios y a largo plazo

Resultados

En total se analizaron 1.428 procedimientos, incluyendo 586 y 842 procedimientos realizados con y sin cirujanos certificados por ESSQS, respectivamente. Tras el emparejamiento, se seleccionaron dos cohortes de 426 pacientes para la comparación de resultados a corto plazo. Se observó una mayor prevalencia de resecciones rectales (50,3% versus 40,1%, P = 0,0001) y un tiempo quirúrgico más corto (230 versus 238 min, P = 0,04) en el grupo ESSQS. Las tasas de complicaciones intra‐ y postoperatorias y de reoperaciones fueron significativamente más bajas en el grupo ESSQS que en el grupo no ESSQS (1,2%, 4,6% y 1,9% versus 3,6%, 7,5% y 3,9%, P = 0,01; 0,03, y 0,02, respectivamente). Estos hallazgos se confirmaron tras el análisis de emparejamiento por puntaje de propensión. El análisis de regresión de Cox mostró que la no participación de cirujanos certificados con ESSQS (razón de oportunidades, odds ratio, OR 12,3; i.c. del 95%, 1,28–119,1; P = 0,03) se asoció independientemente con la recidiva local en los casos en estadio II.

Conclusión

Los procedimientos colorrectales laparoscópicos realizados por cirujanos certificados por ESSQS presentaron mejores resultados postoperatorios. Son necesarios más estudios para determinar el impacto de la certificación en los resultados oncológicos a largo plazo.

Introduction

In 2004, the Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery (JSES) introduced the Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System (ESSQS)1, 2, 3 to maintain and improve the quality of laparoscopic surgery. Candidacy for the ESSQS requires academic achievements (3 conference presentations and 2 papers on laparoscopic surgery), laparoscopic experience (including 20 advanced procedures such as colorectal resection and gastrectomy, or 50 basic procedures such as cholecystectomy and inguinal hernia repair), attendance at JSES official training seminars, and 2 years of general surgical experience after the board certification by the Japan Surgical Society. The examination is based on anonymized unedited random video review and scoring by two or three expert laparoscopic surgeons designated by the JSES. ESSQS‐certified surgeons in the colorectal surgery section are qualified to perform sigmoidectomies for colonic cancer and high anterior resections for rectosigmoid cancer.

Only 20–30 per cent of ESSQS examinees are considered adequate for qualification each year, and currently less than 10 per cent of Japanese general surgeons are ESSQS‐certified. Still, it remains unclear whether technically qualified surgeons could safely perform procedures after ESSQS certification. It has been reported that mentoring and tutoring by an ESSQS‐qualified surgeon are efficient methods for teaching laparoscopic colorectal surgical skills4, and that supervision by an ESSQS‐certified surgeon affects the safety of laparoscopic colectomy performed by a junior surgeon5. However, no large study has investigated whether this qualification can actually improve the safety of the laparoscopic resections.

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of the ESSQS certification on the safety and oncological outcomes of laparoscopic colorectal resections.

Methods

All laparoscopic colorectal resections performed from January 2010 to December 2013 in Hokkaido University Hospital and ten affiliated hospitals were reviewed retrospectively. Inclusion criteria for the study were stage 0, I, II or III confirmed adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum. Patients who had other synchronous or metachronous cancers (excluding in situ cancer) within 5 years and had undergone chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery were excluded.

The ethics committees of Hokkaido University Hospital and all participating hospitals approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, in accordance with the guidelines of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

For each patient, data extracted from records included: clinical features, demographics, presentation, surgical data, postoperative outcome and follow‐up.

Procedures were categorized according to whether they were performed by surgeons with or without the ESSQS qualification, and patients' clinical, pathological and surgical features were used to match subgroups using propensity scoring.

Outcome measures

Groups were compared for differences in short‐ and long‐term outcomes. Short‐term results included: duration of surgery, blood loss, conversion rate, intraoperative complication rate (defined as injury to major vessels, intestinal tract or surrounding organs, or another intraoperative accidental event), postoperative complication rate, reoperation rate, length of postoperative hospital stay, number of harvested lymph nodes, and R0 resection rate. Postoperative complications were assessed according to the Clavien–Dindo classification6. Follow‐up was conducted in day clinics. The 5‐year overall recurrence‐free and local recurrence‐free rates (defined as the time from surgery to recurrence or local recurrence) were compared in patients with pathological stage II and III cancers. In addition, the association between overall and local recurrence and intervention by ESSQS‐qualified or unqualified surgeon was examined in patients with stage II and III cancer.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are reported as mean values with 95 per cent confidence intervals. All statistical tests were performed using an α level of 0·05 (two‐sided). χ2 and Student's t tests were used for categorical and non‐normal continuous data respectively.

The following clinical, surgical and pathological features were selected as factors for propensity score matching: age, sex, BMI, ASA fitness grade, previous laparotomy, obstruction, cT status, cN status, clinical stage, procedure, anastomosis, lymph node dissection (D1, D2 or D3) and diverting stoma. Propensity scores were generated using multivariable logistic regression models with attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons as the outcome.

Survival curves for the studied groups were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log rank test. Cox regression with co‐variable adjustment was performed separately for patients with stage II and those with stage III disease, with selected prognostic values (attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeon, rectal cancer, age, sex, primary tumour size and depth, lymph node metastasis, extent of lymph node dissection, BMI, ASA grade, occurrence of postoperative complication, R status, tumour differentiation, adjuvant chemotherapy, and lymph and venous vessel invasion of the primary lesion). Simple linear regression was performed to assess the relationship between institutional heterogeneity (number of beds, annual volume of colorectal cancer surgery, number of surgeons, and the proportion of operations performed or attended by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons in each institution) and the rate of postoperative complications.

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP® Pro version 14.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

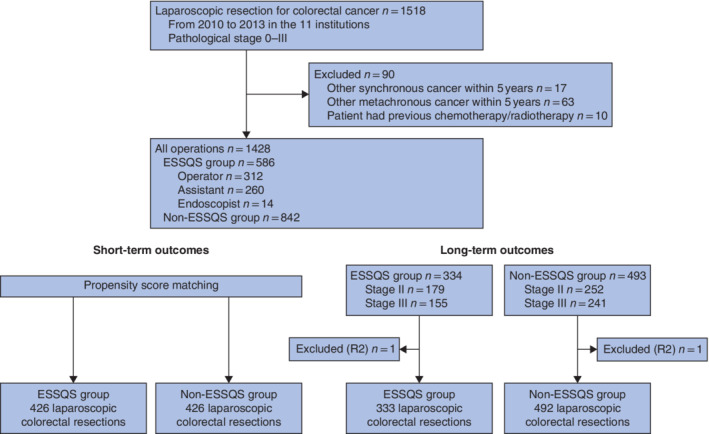

A total of 1428 laparoscopic colorectal procedures that met the inclusion criteria were performed in 2010–2013, including 586 procedures performed with or by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons and 842 procedures performed by non‐ESSQS‐qualified surgeons. Seven ESSQS‐qualified surgeons attended 177, 154, 143, 102, seven, two and one operation respectively. Each ESSQS‐qualified surgeon contributed as an operator (312 operations), assistant (260) or endoscopist (14) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System.

Institutional characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean number of beds was 507·0 and a mean of 519·5 and 92·0 annual cases of general surgery and colorectal surgery were identified, respectively. The mean number of attending surgeons was 6·7 and the rate of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancers was 48·9 per cent. There was no correlation between the proportion of operations attended by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons and institutional volume (number of beds: R2 = 0.08, P = 0.397; general surgery volume: R2 = 0.10, P = 0.334; colorectal surgery volume: R2 = 0.06, P = 0.515).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 11 institutions

| Institution | % of operations attended by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons | No. of beds | No. of surgeons | Annual no. of colorectal operations | % of colorectal operations done laparoscopically | No. of registered patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 97 | 944 | 5 | 47 | 75 | 92 |

| B | 71·3 | 519 | 14 | 172 | 44·6 | 254 |

| C | 88 | 382 | 5 | 74 | 78 | 155 |

| D | 0 | 747 | 8 | 98 | 42 | 160 |

| E | 3 | 539 | 10 | 145 | 40·5 | 133 |

| F | 13·6 | 410 | 5 | 91 | 50 | 132 |

| G | 47·0 | 358 | 4 | 64 | 51 | 115 |

| H | 100 | 498 | 4 | 65 | 51 | 102 |

| I | 0 | 300 | 6 | 65 | 43 | 99 |

| J | 0 | 430 | 5 | 81 | 38 | 97 |

| K | 1 | 450 | 8 | 110 | 24·4 | 89 |

| Mean | 38·3 | 507·0 | 6·7 | 92·0 | 48·9 | 129·8 |

ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System.

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2. A total of 337 men and 249 women with a mean age of 67·6 years were treated in the ESSQS group, and 474 men and 368 women with a mean age of 68·5 years had surgery performed by non‐ESSQS‐qualified surgeons. No differences in BMI or history of previous surgery were observed between the two groups. The frequency of preoperative co‐morbidity with ASA grade III or above was higher in the ESSQS group than in the non‐ESSQS group (13·5 versus 8·2 per cent respectively; P = 0·013). In addition, 3·4 and 1·8 per cent of patients in the ESSQS and non‐ESSQS groups respectively had a preoperative obstruction due to the tumour that required decompression (P = 0·049). The ESSQS group had more patients who underwent rectal resection (295 (50·3 per cent) versus 341 (40·5 per cent); P < 0·001) and D3 lymph node dissection (67·1 versus 60·9 per cent; P = 0·007) than the non‐ESSQS group. The types of colonic anastomosis and the frequency of double‐stapling technique using linear and circular staplers in the entire cohort were different between the two groups. Moreover, combined resection of surrounding organs was performed significantly more in the ESSQS group (2·0 versus 0·6 per cent; P = 0·025). Surrounding organs involved in combined resections included the small bowel (5), uterus and its adnexa (3), ureter (1) and bladder (3) in the ESSQS group and small bowel (2), uterus and its adnexa (2) and bladder (1) in the non‐ESSQS group.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| ESSQS group (n = 586) | Non‐ESSQS group (n = 842) | P ‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) * | 67·6 (66·7–68·5) | 68·5 (67·8–69·3) | 0·143§ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 337 : 249 | 474 : 368 | 0·649 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) * | 23·1 (22·9–23·5) | 23·0 (22·7–23·3) | 0·427§ |

| ASA fitness grade III–IV | 79 (13·5) | 69 (8·2) | 0·013 |

| Previous laparotomy | 144 (24·6) | 209 (24·8) | 0·915 |

| Obstruction | 20 (3·4) | 15 (1·8) | 0·049 |

| Tumour location | 0·046 | ||

| Colon | 390 (66·6) | 602 (71·5) | |

| Rectum | 196 (33·4) | 240 (28·5) | |

| cT category | 0·136 | ||

| cT0 | 27 (4·6) | 36 (4·3) | |

| cT1 | 152 (25·9) | 197 (23·4) | |

| cT2 | 108 (18·4) | 159 (18·9) | |

| cT3 | 272 (46·4) | 383 (45·5) | |

| cT4 | 27 (4·6) | 67 (8·0) | |

| cN category | 0·002 | ||

| cN0 | 481 (82·1) | 633 (75·2) | |

| cN1 | 77 (13·1) | 172 (20·4) | |

| cN2 | 25 (4·3) | 36 (4·3) | |

| cN3 | 3 (0·5) | 1 (0·1) | |

| Clinical stage | 0·021 | ||

| 0 | 27 (4·6) | 36 (4·3) | |

| I | 249 (42·5) | 323 (38·4) | |

| II | 205 (35·0) | 274 (32·5) | |

| III | 105 (17·7) | 209 (24·8) | |

| Procedure† | < 0·001 | ||

| Right colectomy | 154 (26·3) | 284 (33·7) | |

| Transverse colectomy | 33 (5·6) | 35 (4·2) | |

| Left colectomy | 21 (3·6) | 31 (3·7) | |

| Sigmoidectomy | 78 (13·3) | 149 (17·7) | |

| High anterior resection | 157 (26·8) | 182 (21·6) | |

| Low anterior resection | 101 (17·2) | 147 (17·5) | |

| Hartmann procedure | 13 (2·2) | 0 (0) | |

| ISR | 3 (0·5) | 0 (0) | |

| APR | 21 (3·6) | 12 (1·4) | |

| Total coloproctectomy | 3 (0·5) | 2 (0·2) | |

| Combined resection | |||

| Surrounding organ | 12 (2·0) | 5 (0·6) | 0·025 |

| Multiple procedures | 15 (2·6) | 33 (3·9) | 0·160 |

| Anastomosis † | < 0·001 | ||

| FEEA | 127 (21·7) | 388 (46·1) | |

| Triangular | 155 (26·5) | 47 (5·6) | |

| Albert–Lembert method | 0 (0) | 36 (4·3) | |

| Side‐to‐end | 2 (0·3) | 11 (1·3) | |

| DST | 258 (44·0) | 328 (39·0) | |

| CAA or IAA | 6 (1·0) | 0 (0) | |

| Lymph node dissection † | 0·007 | ||

| D1 | 15 (2·6) | 37 (4·4) | |

| D2 | 178 (30·4) | 287 (34·1) | |

| D3 | 393 (67·1) | 513 (60·9) | |

| LLND | 7 (1·2) | 5 (0·6) | 0·353 |

| Diverting stoma | 39 (6·7) | 21 (2·5) | < 0·001 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean (95 per cent c.i.).

Indicates some missing data. ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System; ISR, intersphincteric resection; APR, abdominoperineal resection; FEEA, functional end‐to‐end anastomosis; DST, double‐stapling technique; CAA, coloanal anastomosis; IAA, ileal J pouch–anal anastomosis; LLND, lateral lymph node dissection.

χ2 test, except §Student's t test.

Short‐term outcomes

Duration of surgery (230 versus 238 min; P = 0·045) and postoperative hospital stay (14·5 versus 16·3 days; P = 0·002) were significantly shorter in the ESSQS group. Intraoperative and postoperative complication rates (grade III or above) were 1·2 and 4·6 per cent respectively in the ESSQS group, and 3·6 and 7·5 per cent in the non‐ESSQS group (Table 3). Significant differences in intraoperative accidental bleeding from major vessels and postoperative anastomotic leakage were observed between the groups. The reoperation rate was also significantly lower in the ESSQS group than in the non‐ESSQS group (1·9 versus 3·9 per cent; P = 0·023), particularly reoperation due to anastomotic leak (0·7 versus 2·3 per cent; P = 0·035). No differences in conversion rate, blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes or pathological R0 rate were found (Table 3).

Table 3.

Operative outcomes

| ESSQS group (n = 586) | Non‐ESSQS group (n = 842) | P ‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of surgery (min) * | 230 (224–237) | 238 (234–244) | 0·045§ |

| Blood loss (ml) * | 51·7 (38·9–64·4) | 59·7 (49·0–70·4) | 0·342§ |

| Conversion | 16 (2·7) | 32 (3·8) | 0·270 |

| Intraoperative complication | 7 (1·2) | 30 (3·6) | 0·014 |

| Bleeding | 1 (0·2) | 13 (1·5) | 0·021 |

| Injury to intestinal tract | 2 (0·3) | 4 (0·5) | 0·999 |

| Injury to surrounding organs | 3 (0·5) | 8 (1·0) | 0·533 |

| Other | 1 (0·2) | 5 (0·6) | 0·424 |

| Postoperative complication † | 27 (4·6) | 63 (7·5) | 0·025 |

| Bleeding | 3 (0·5) | 3 (0·4) | 0·975 |

| Superficial SSI | 0 (0) | 3 (0·4) | 0·390 |

| Deep SSI | 2 (0·3) | 4 (0·5) | 0·999 |

| Anastomotic leak | 7 (1·2) | 31 (3·7) | 0·007 |

| Ileus | 4 (0·7) | 12 (1·4) | 0·291 |

| Cardiac, pulmonary or cerebral | 3 (0·5) | 0 (0) | 0·136 |

| Other | 8 (1·4) | 10 (1·2) | 0·956 |

| Reoperation | 11 (1·9) | 33 (3·9) | 0·023 |

| Bleeding | 1 (0·2) | 2 (0·2) | 0·990 |

| Deep SSI | 0 (0) | 1 (0·1) | 0·999 |

| Anastomotic leak | 4 (0·7) | 19 (2·3) | 0·035 |

| Ileus | 3 (0·5) | 4 (0·5) | 0·999 |

| Other | 3 (0·5) | 7 (0·8) | 0·697 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) * | 14·5 (13·6–15·4) | 16·3 (15·6–17·1) | 0·002§ |

| No. of harvested lymph nodes * | 18·0 (17·2–19·0) | 18·3 (17·6–19·1) | 0·681§ |

| Pathological R0 resection | 570 (97·3) | 832 (98·8) | 0·099 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean (95 per cent c.i.).

Grade III or above according to the Clavien–Dindo classification. ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System.

χ2 test, except §Student's t test.

For rectal resections, both high and low anterior resections were performed more quickly in the ESSQS group (high anterior resection: mean 222 versus 244 min, P = 0·001; low anterior resection: 280 versus 309 min, P = 0·004). Blood loss was also lower in the ESSQS group for low anterior resection (43·0 versus 73·7 ml; P = 0·039), as were the intraoperative complication (0 versus 6·1 per cent; P = 0·002) and conversion (2·0 versus 6·8 per cent; P = 0·066) rates. The intraoperative complication rate for sigmoidectomy performed by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons was lower (0 versus 4·7 per cent; P = 0·014), as was the reoperation rate for right colectomy (0·6 versus 3·5 per cent; P = 0·042) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Short‐term outcomes by procedure

| ESSQS group (n = 586) | Non‐ESSQS group (n = 842) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of surgery (min) | |||

| Right colectomy | 204 (195–214) | 210 (203–217) | 0·353‡ |

| Transverse colectomy | 220 (194–246) | 210 (184–235) | 0·575‡ |

| Left colectomy | 227 (192–263) | 238 (209–266) | 0·650‡ |

| Sigmoidectomy | 206 (191–222) | 215 (204–227) | 0·344‡ |

| High anterior resection | 222 (213–232) | 244 (235–253) | 0·001‡ |

| Low anterior resection | 280 (266–296) | 309 (297–322) | 0·004‡ |

| Blood loss (ml) | |||

| Right colectomy | 69·4 (34·2–104·6) | 65·5 (39·5–91·5) | 0·857‡ |

| Transverse colectomy | 47·7 (19·5–75·7) | 34·5 (7·2–61·9) | 0·507‡ |

| Left colectomy | 28·2 (−37·6–93·9) | 81·4 (33·2–141·5) | 0·169‡ |

| Sigmoidectomy | 52·8 (25·8–80·0) | 44·1 (24·3–63·8) | 0·653‡ |

| High anterior resection | 25·8 (11·4–40·2) | 40·5 (26·9–54·1) | 0·145‡ |

| Low anterior resection | 43·0 (20·7–65·4) | 73·7 (55·1–92·3) | 0·039‡ |

| Intraoperative complication | |||

| Right colectomy | 4 of 154 (2·6) | 5 of 284 (1·7) | 0·562 |

| Transverse colectomy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Left colectomy | 0 (0) | 2 of 31 (6) | 0·235 |

| Sigmoidectomy | 0 (0) | 7 of 149 (4·7) | 0·014 |

| High anterior resection | 2 of 157 (1·3) | 7 of 182 (3·8) | 0·124 |

| Low anterior resection | 0 (0) | 9 of 147 (6·1) | 0·002 |

| Conversion | |||

| Right colectomy | 5 of 154 (3·2) | 9 of 284 (3·2) | 0·964 |

| Transverse colectomy | 2 of 33 (6) | 0 (0) | 0·139 |

| Left colectomy | 1 of 21 (5) | 2 of 31 (6) | 0·798 |

| Sigmoidectomy | 1 of 78 (1) | 3 of 149 (2·0) | 0·691 |

| High anterior resection | 3 of 157 (1·9) | 7 of 182 (3·8) | 0·276 |

| Low anterior resection | 2 of 101 (2·0) | 10 of 147 (6·8) | 0·066 |

| Postoperative complication | |||

| Right colectomy | 9 of 154 (5·8) | 18 of 284 (6·3) | 0·837 |

| Transverse colectomy | 1 of 33 (3) | 2 of 35 (6) | 0·590 |

| Left colectomy | 3 of 21 (14) | 3 of 31 (10) | 0·610 |

| Sigmoidectomy | 2 of 78 (3) | 9 of 149 (6·0) | 0·247 |

| High anterior resection | 5 of 157 (3·1) | 10 of 182 (5·5) | 0·286 |

| Low anterior resection | 6 of 101 (5·9) | 16 of 147 (10·9) | 0·169 |

| Reoperation | |||

| Right colectomy | 1 of 154 (0·6) | 10 of 284 (3·5) | 0·042 |

| Transverse colectomy | 0 (0) | 1 of 35 (3) | 0·246 |

| Left colectomy | 3 of 21 (14) | 3 of 31 (10) | 0·610 |

| Sigmoidectomy | 0 (0) | 4 of 149 (2·7) | 0·065 |

| High anterior resection | 2 of 157 (1·3) | 4 of 182 (2·2) | 0·505 |

| Low anterior resection | 4 of 101 (4·0) | 10 of 147 (6·8) | 0·324 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean (95 per cent c.i.). ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System.

χ2 test, except

Student's t test.

Short‐term outcomes in the propensity score‐matched cohort

Short‐term outcomes were also compared following propensity score matching. Some 426 patients from each group were included in the matched cohort. After matching, each ESSQS‐qualified surgeon in the ESSQS group contributed as an operator (214), assistant (202) or endoscopist (10). There was no difference between groups for any preoperative factor or procedure (age, sex, BMI, ASA grade, previous laparotomy, obstruction, tumour location, cT and cN status, clinical stage, type of procedure, combined resection, anastomosis, lymph node dissection, lateral lymph node dissection and diverting stoma). Duration of surgery (226 versus 249 min; P = 0·001) and postoperative hospital stay (13·7 versus 17·5 days; P < 0·001) were significantly shorter in the ESSQS group. Intraoperative and postoperative complication rates (grade III or above) were 1·6 and 4·7 per cent respectively in the ESSQS group and 4·2 and 9·9 per cent in the non‐ESSQS group (Table 5). Significant differences in intraoperative accidental bleeding from major vessels (0·2 versus 1·8 per cent; P = 0·021) and postoperative anastomotic leakage (1·4 versus 5·2 per cent; P = 0·002) were observed between the groups. The reoperation rate was also lower in the ESSQS group than in the non‐ESSQS group (1·6 versus 4·9 per cent; P = 0·007), particularly that due to anastomotic leakage (0·7 versus 3·3 per cent; P = 0·014). No differences in conversion rate, blood loss, number of harvested lymph nodes, and pathological R0 rate were found (Table 5).

Table 5.

Patient characteristics and short‐term surgical outcomes in the propensity score‐matched cohort

| ESSQS group (n = 426) | Non‐ESSQS group (n = 426) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) * | 67·4 (66·4–68·5) | 67·4 (66·4–58·5) | 0·989‡ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 247 : 179 | 250 : 176 | 0·835 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) * | 23·2 (22·9–23·6) | 23·0 (22·7–23·4) | 0·447‡ |

| Tumour location | 0·310 | ||

| Colon | 270 (63·4) | 256 (60·0) | |

| Rectum | 156 (36·6) | 170 (40·0) | |

| Clinical stage | 0·868 | ||

| 0 | 21 (4·9) | 21 (4·9) | |

| I | 185 (43·4) | 173 (40·6) | |

| II | 131 (30·8) | 138 (32·4) | |

| III | 89 (20·9) | 94 (22·1) | |

| Procedure | 0·945 | ||

| Right colectomy | 110 (25·8) | 111 (26·1) | |

| Transverse colectomy | 18 (4·2) | 14 (3·3) | |

| Left colectomy | 14 (3·3) | 9 (2·1) | |

| Sigmoidectomy | 42 (9·9) | 40 (9·4) | |

| High anterior resection | 142 (33·3) | 149 (35·0) | |

| Low anterior resection | 88 (20·7) | 91 (21·4) | |

| APR | 11 (2·6) | 10 (2·3) | |

| Other | 1 (0·2) | 2 (0·5) | |

| Anastomosis | n = 415 | n = 415 | 0·537 |

| FEEA | 125 (30·1) | 125 (30·1) | |

| Triangular anastomosis | 55 (13·3) | 47 (11·3) | |

| DST | 230 (55·4) | 241 (58·1) | |

| Other | 5 (1·2) | 2 (0·5) | |

| Lymph node dissection | 0·956 | ||

| D1 | 12 (2·8) | 12 (2·8) | |

| D2 | 133 (31·2) | 129 (30·3) | |

| D3 | 281 (66·0) | 285 (66·9) | |

| Diverting stoma | 17 (4·0) | 20 (4·7) | 0·614 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Duration of surgery (min)* | 226 (219–234) | 249 (241–256) | 0·001‡ |

| Blood loss (ml)* | 48·7 (35·6–61·8) | 57 9 (44·7–71·0) | 0·329‡ |

| Conversion | 9 (2·1) | 16 (3·8) | 0·153 |

| Intraoperative complication | 7 (1·6) | 18 (4·2) | 0·025 |

| Postoperative complication | 20 (4·7) | 42 (9·9) | 0·003 |

| Reoperation | 7 (1·6) | 21 (4·9) | 0·007 |

| No. of harvested lymph nodes* | 17·5 (16·4–18·6) | 18·9 (17·8–20·0) | 0·078‡ |

| Pathological R0 resection | 416 (97·7) | 420 (98·6) | 0·449 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean (95 per cent c.i.). ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System; APR, abdominoperineal resection; FEEA, functional end‐to‐end anastomosis; DST, double‐stapling technique.

χ2 test, except

Student's t test.

Pathological outcomes and survival

Overall, no differences in tumour depth, node status, pathological stage or tumour size were observed between subgroups. However, the ESSQS group had a higher rate of adenocarcinoma with undifferentiated features (20·0 versus 14·4 per cent; P = 0·007) (Table 6). The rate of lymph vessel invasion in the ESSQS and non‐ESSQS group was 51·0 and 40·6 per cent respectively (P < 0·001), and the venous vessel invasion rate was 51·2 and 41·6 per cent (P < 0·001).

Table 6.

Pathological features

| ESSQS group (n = 586) | Non‐ESSQS group (n = 842) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pT category | |||

| pT0 | 32 (5·5) | 49 (5·8) | 0·695 |

| pT1a | 7 (1·2) | 9 (1·1) | |

| pT1b | 140 (23·9) | 180 (21·4) | |

| pT2 | 95 (16·2) | 163 (19·4) | |

| pT3 | 269 (45·9) | 382 (45·4) | |

| pT4a | 35 (6·0) | 48 (5·7) | |

| pT4b | 8 (1·4) | 11 (1·3) | |

| pN category | |||

| pN0 | 427 (72·9) | 598 (71·0) | 0·491 |

| pN1 | 122 (20·8) | 199 (23·6) | |

| pN2 | 31 (5·3) | 40 (4·8) | |

| pN3 | 6 (1·0) | 5 (0·6) | |

| Pathological stage | |||

| 0 | 39 (6·7) | 49 (5·8) | 0·784 |

| I | 213 (36·3) | 300 (35·6) | |

| II | 179 (30·5) | 252 (29·9) | |

| III | 155 (26·5) | 241 (28·6) | |

| Tumour size (mm) * | 34·5 (32·8–36·2) | 34·4 (33·0–35·9) | 0·939‡ |

| No. of metastatic nodes * | 0·79 (0·61–0·98) | 0·73 (0·58–0·89) | 0·617‡ |

| Lymph vessel invasion | 299 (51·0) | 342 (40·6) | < 0·001 |

| Venous vessel invasion | 300 (51·2) | 350 (41·6) | < 0·001 |

| Differentiated adenocarcinoma | 553 (94·4) | 805 (95·6) | 0·287 |

| With undifferentiated features | 116 (20·0) | 121 (14·4) | 0·007 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||

| Stage II | 56 of 179 (31·3) | 36 of 252 (14·3) | < 0·001 |

| Stage III | 108 of 155 (69·7) | 173 of 241 (71·8) | 0·652 |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are mean (95 per cent c.i.). ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System.

χ2 test, except

Student's t test.

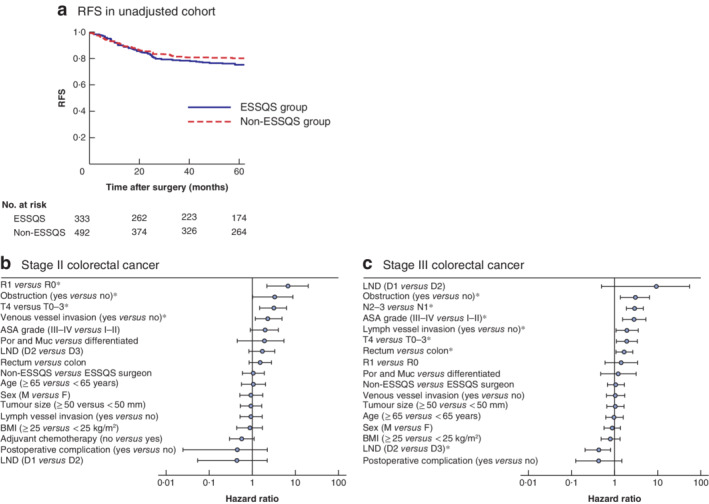

The median length of follow‐up was 60 months for both groups. Of 333 patients in the ESSQS group 31 (9·3 per cent) were lost to follow‐up, and of 492 patients in the non‐ESSQS group 39 (7·9 per cent) were lost to follow‐up (P = 0·485). The 5‐year overall recurrence‐free survival rates for patients with stage II–III cancers were 76·1 (95 per cent c.i. 71·0 to 80·6) and 80·5 (76·5 to 83·9) per cent in the ESSQS and non‐ESSQS group respectively (P = 0·221) (Fig. 2 a).

Figure 2.

Association between intervention by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons and recurrence‐free survival in patients with stage II and III cancers a Kaplan–Meier analysis of recurrence‐free survival (RFS) in an unadjusted cohort of patients with stage II and III colorectal cancer operated on by ESSQS‐certified or non‐ESSQS‐qualified surgeons. P = 0·221 (log rank test). b,c Cox regression analysis of recurrence. Hazard ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals for each risk factor for patients with stage II (b) and stage III (c) disease. *P < 0·050. ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System; LND, lymph node dissection; Por, poorly differentiated; Muc, mucinous.

In Cox regression analysis for stage II and stage III disease (excluding R2), R1 resection, obstruction, T4 status and venous vessel invasion were significantly associated with recurrence in stage II, whereas obstruction, node status, high ASA grade, lymph vessel invasion, T4 status and rectal cancer were significantly associated with recurrence in stage III. However, attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons was not an independent factor (stage II: hazard ratio (HR) 1·05, 95 per cent c.i. 0·58 to 1·89, P = 0·881; stage III: HR 1·07, 0·69 to 1·67, P = 0·761) (Fig. 2 b,c).

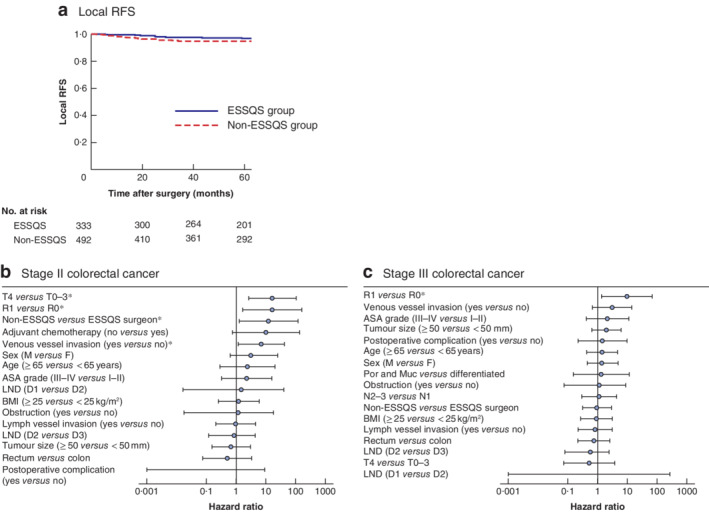

There were eight local recurrences in the ESSQS group and 22 in the non‐ESSQS group. In the ESSQS group, local recurrence occurred in the peritoneum or retroperitoneum around the primary site (4 patients), lesional lymph node (3) and anastomotic site (1), and in the non‐ESSQS group local recurrence was observed in the peritoneum or retroperitoneum around the primary site (16), lesional lymph node (3), anastomotic site (2), and both the peritoneum and anastomotic site (1). The 5‐year overall local recurrence‐free survival rate for pathological stage II–III cancers was 96·9 and 94·6 per cent in the ESSQS and non‐ESSQS group respectively (P = 0·092). In Cox regression analysis for stage II and III disease (excluding R2), non‐attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons (HR 12·30, 95 per cent c.i. 1·28 to 119·10; P = 0·038), T4 status, R1 resection and venous vessel invasion were associated with local recurrence in stage II, whereas attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons was not an independent factor associated with recurrence in stage III (HR 0·53, 95 per cent c.i. 0·14 to 1·85; P = 0·317) (Fig. 3 b,c).

Figure 3.

Association between intervention by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons and local recurrence‐free survival in patients with stage II and III cancers a Kaplan–Meier analysis of local recurrence‐free survival (RFS) in patients with stage II and III colorectal cancer operated on by ESSQS‐certified or non‐ESSQS‐qualified surgeons. P = 0·092 (log rank test). b,c Cox regression analysis of local recurrence. Hazard ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals for each risk factor for patients with stage II (b) and stage III (c) disease. *P < 0·050. ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System; LND, lymph node dissection; Por, poorly differentiated; Muc, mucinous.

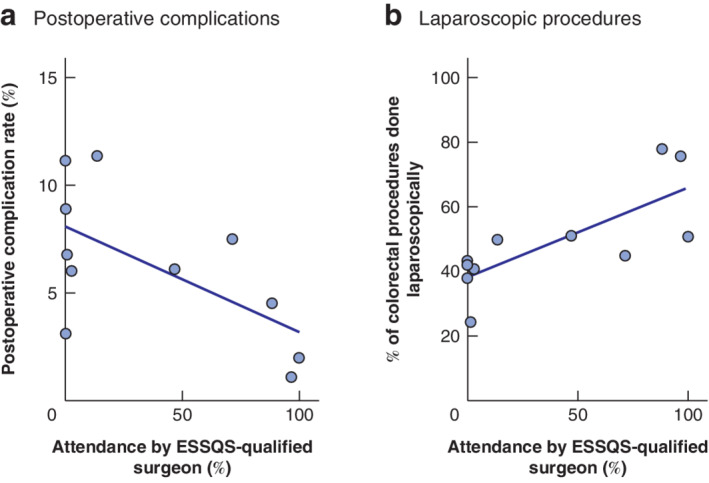

Relationship between institutional heterogeneity and postoperative complications

The rate of postoperative complications was related to the proportion of procedures that ESSQS surgeons participated in (R 2 = 0·39, P = 0·041), but had no relationship with the number of beds, annual volume of colorectal cancer procedures or number of surgeons (data not shown). Furthermore, the proportion of colorectal operations that were performed laparoscopically increased along with the proportion of operations that ESSQS surgeons participated in (R 2 = 0·57, P = 0·007) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between the proportion of procedures attended by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons and the postoperative complication rate, and the proportion of colorectal procedures done laparoscopically a Postoperative complication rate in each institution. R 2 = 0·29, P = 0·041 (linear regression). b Proportion of colorectal procedures done laparoscopically. R 2 = 0·57, P = 0·007 (linear regression). ESSQS, Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System.

Discussion

In this study, the superiority of attendance over non‐attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons in laparoscopic colorectal resection was apparent in terms of duration of surgery, intraoperative and postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo grade III or above) rates, reoperation rate and length of postoperative hospital stay. More difficult cases were reported in the ESSQS group, such as rectal cancer, patients with obstruction and high ASA grade. The procedures performed by ESSQS‐qualified surgeons were also considered to be more advanced, such as rectal resection and D3 lymph node dissection. Nevertheless, the ESSQS group had significantly shorter duration of surgery and postoperative hospital stay, lower intraoperative and postoperative complication rates, and a lower reoperation rate than the non‐ESSQS group. Additionally, the differences in duration of surgery and intraoperative complication rate were significant for advanced procedures such as anterior rectal resection. These results support the supposition that the ESSQS‐qualified surgeons have improved laparoscopic surgical skills and provide better short‐term outcomes.

These findings were further validated in the propensity score‐matched cohort. Similarly, the mean duration of surgery (226 min), blood loss (48·7 ml), conversion rate (2·1 per cent), postoperative complication rate (Clavien–Dindo grade III or above, 4·7 per cent) and reoperation rate (1·6 per cent) in the ESSQS group were comparable to the respective values of 211 min, 30 ml, 5·4 per cent, 4·6 per cent (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0 grade 3 or above) and 1·7 per cent reported in the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) 0404 study, a nationwide RCT investigating the safety of laparoscopic colectomy performed by expert surgeons7.

Among patients with stage II and III disease, local recurrence was improved in the ESSQS group compared with that in the non‐ESSQS group. In particular, non‐attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons was one of the independent risk factors for local recurrence in patients with stage II disease. However, in patients with stage III disease, the local recurrence rate was similar in the two groups, although these long‐term outcomes should be validated in larger studies. The recurrence‐free survival rate of patients with stage II–III cancers in the ESSQS group was 76·1 (95 per cent c.i. 71·0 to 80·6) per cent, which is comparable to the rate of 79 (75·6 to 82·6) per cent in the JCOG 0404 study with similar patient distributions8.

The present study is representative of real‐world practice. In 2010, laparoscopic colorectal surgery was performed in more than ten colorectal procedures per year in the 13 institutions affiliated to the Hokkaido University, although only ten of these institutions agreed to participate in the study. Therefore, there was a slight bias in the selection of institutions. A number of studies9, 10 have reported that hospital case volume or surgeon volume is associated with short‐ and long‐term outcomes in some types of cancer, including colorectal cancer. However, in the present study, the postoperative complication rate was not associated with the number of beds, annual volume of colorectal cancer procedures or number of surgeons, but was related to the attendance of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons.

This study has some other limitations. As it was not a prospective study or an RCT, there were several differences in patients' backgrounds. Furthermore, it was a regional study limited to Hokkaido Prefecture rather than nationwide, and the numbers of attending ESSQS‐qualified surgeons and advanced rectal cancers were small. Over 30 per cent of patients with low rectal cancer undergo low anterior resection using the laparoscopic approach in Japan11. However, both the short‐term safety of this procedure in the general setting and the long‐term safety have not been well established12, 13, 14, 15. Clarifying the value of ESSQS‐qualified surgeons in the performance of safe laparoscopic rectal resection is one of the issues that needs to be resolved. Finally, the circumstances surrounding laparoscopic colorectal resection are changing. The rate of laparoscopic surgery has increased year on year compared with that of open surgery, and young surgeons have more opportunity to learn and perform laparoscopic surgery safely16. In the future, nationwide studies will help to clarify fully the relevance of the ESSQS in colorectal surgical laparoscopic practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank H. Ishizu, S. Takahashi, H. Yamagami, Y. Ohno, Y. Tanaka, S. Matsuoka, K. Misawa, M. Sunahara, K. Okuda, T. Katayama, Y. Terasaki, H. Akabane, M. Koike, H. Kon, D. Kuraya, C. Shirakawa, R. Ueda, K. Sato, H. Shomura, K. Taguchi, K. Ogasawara, T. Hamada, H. Abe, H. Matsui and A. Sawada for their help with data collection and useful discussion.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding information

No funding

References

- 1. Kimura T, Mori T, Konishi F, Kitajima M. Endoscopic surgical skill qualification system in Japan: five years of experience in the gastrointestinal field. Asian J Endosc Surg 2010; 3: 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yamakawa T, Kimura T, Matsuda T, Konishi F, Bandai Y. Endoscopic Surgical Skill Qualification System (ESSQS) of the Japanese Society of Endoscopic Surgery (JSES). BH Surg 2013; 3: 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mori T, Kimura T, Kitajima M. Skill accreditation system for laparoscopic gastroenterologic surgeons in Japan. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 2010; 19: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ichikawa N, Homma S, Yoshida T, Ohno Y, Kawamura H, Wakizaka K et al Mentor tutoring: an efficient method for teaching laparoscopic colorectal surgical skills in a general hospital. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2017; 27: 479–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ichikawa N, Homma S, Yoshida T, Ohno Y, Kawamura H, Kamiizumi Y et al Supervision by a technically qualified surgeon affects the proficiency and safety of laparoscopic colectomy performed by novice surgeons. Surg Endosc 2018; 32: 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamamoto S, Inomata M, Katayama H, Mizusawa J, Etoh T, Konishi F et al; Japan Clinical Oncology Group Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Short‐term surgical outcomes from a randomized controlled trial to evaluate laparoscopic and open D3 dissection for stage II/III colon cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG 0404. Ann Surg 2014; 260: 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kitano S, Inomata M, Mizusawa J, Katayama H, Watanabe M, Yamamoto S et al Survival outcomes following laparoscopic versus open D3 dissection for stage II or III colon cancer (JCOG0404): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 2: 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Massarotti H, Rodrigues F, O'Rourke C, Chadi SA, Wexner S. Impact of surgeon laparoscopic training and case volume of laparoscopic surgery on conversion during elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis 2017; 19: 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Neree Tot Babberich MPM, van Groningen JT, Dekker E, Wiggers T, Wouters MWJM et al; Dutch Surgical Colorectal Audit . Laparoscopic conversion in colorectal cancer surgery; is there any improvement over time at a population level?. Surg Endosc 2018; 32: 3234–3246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsubara N, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Tomita N, Baba H, Kimura W et al Mortality after common rectal surgery in Japan: a study on low anterior resection from a newly established nationwide large‐scale clinical database. Dis Colon Rectum 2014; 57: 1075–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, Kim S, Kang SB, Lim SB et al Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid‐rectal or low‐rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open‐label, non‐inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 767–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, Cuesta MA, van der Pas MH, de Lange‐de Klerk ES et al; COLOR II Study Group . A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1324–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stevenson AR, Solomon MJ, Lumley JW, Hewett P, Clouston AD, Gebski VJ et al; ALaCaRT Investigators . Effect of laparoscopic‐assisted resection vs open resection on pathological outcomes in rectal cancer: the ALaCaRT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314: 1356–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ, Boller AM, George V, Abbas M et al Effect of laparoscopic‐assisted resection vs open resection of stage II or III rectal cancer on pathologic outcomes: the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314: 1346–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Homma S, Kawamata F, Yoshida T, Ohno Y, Ichikawa N, Shibasaki S et al The balance between surgical resident education and patient safety in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: surgical resident's performance has no negative impact. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2017; 27: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]