Abstract

Migratory birds are potential transmitters of bacterial antibiotic resistance. However, their role in the environmental dissemination of bacterial antibiotic resistance and the extent of their impact on the environment are not yet clear. Qinghai Lake is one of the most important breeding and stopover ground for the migratory birds along the Central Asian Flyway. Here, we investigated the bacterial antibiotic resistance in the environment and among the migratory birds around the lake. The results of culture-based analysis of bacterial antibiotic resistance, quantitative PCR and metagenomic sequencing indicate that migratory birds are one major source of bacterial antibiotic resistance in the environment around Qinghai Lake. Network analysis reveals the co-occurrence patterns of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and bacterial genera. Genetic co-localization analysis suggests high co-selection potential (with incidence of 35.8%) among different ARGs, but limited linkage (with incidence of only 3.7%) between ARGs and biocide/metal resistance genes (BMRGs). The high genetic linkage between ARGs and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) is still largely confined to the bacterial community in migratory birds (accounting for 96.0% of sequencing reads of MGE-linked ARGs), which indicates limited horizontal transfer of ARGs to the environment. Nevertheless, the antibiotic resistance determinants carried by migratory birds and their specific genetic properties (high co-selection and mobility potential of the ARGs) remind us that the role of migratory birds in the environmental dissemination of bacterial antibiotic resistance deserves more attention.

Keywords: Antibiotic resistance gene, Migratory birds, Environmental dissemination, Biocide/metal resistance gene, Mobile genetic element, Horizontal gene transfer

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Migratory birds are a major source of antibiotic resistance around Qinghai Lake.

-

•

Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes is confined in migratory birds.

-

•

There is high co-selection potential between antibiotic resistance genes.

-

•

Migratory birds deserve more attention for spreading antibiotic resistance.

1. Introduction

Thousands of tons of antibiotics are consumed annually in medical and agricultural settings worldwide (Van Boeckel et al., 2015). The discharge of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant bacteria at hotspots (waste water treatment plants, aquaculture ponds and animal farm) leads to the environmental dissemination of bacterial antibiotic resistance (Knapp et al., 2010). The resulting proliferation and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs all over the world pose a great threat to human and animal health (Berendonk et al., 2015). The activities of wild life, especially those migratory ones, aggravate this situation, which can mediate the international transfer or the transfer to remote area of bacterial antibiotic resistance (Cristobal-Azkarate et al., 2014; Hernando-Amado et al., 2019).

Due to their high mobility, migratory birds have attracted the attention of scientists during the outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza for their role in global dissemination of influenza virus (Liu et al., 2005; Normile, 2006; Olsen et al., 2006). The number of migratory birds worldwide is as high as 5 billion a year (Guenther et al., 2012). Their migration flyways cover all continents including the Antarctica. The role of migratory birds in facilitating the transfer of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes has been gradually recognized (Guenther et al., 2012; Atterby et al., 2016; Ramey et al., 2018; Marcelino et al., 2019). The potential of intercontinental transportation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes via avian migration was also proposed (Liakopoulos et al., 2016; Mohsin et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2020).

Qinghai Lake is the largest salt-water lake in China and one of the most important breeding and stopover grounds for many migratory birds along the Central Asian Flyway. Qinghai Lake is in the northeastern part of Qinghai province. The lake is less affected by human activities due to the official protection and National Nature Reserve policies. However, >150,000 migratory birds use this lake as breeding or stopover ground annually (Zheng et al., 2018). In our previous work, we reported the transportation of bacterial antibiotic resistance from a polluted urban river (Jin River, Chengdu, China) to surrounding environment (Wangjianglou Park) mediated by the wild birds (the egrets) (Wu et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2020). In the similar manner, the migratory birds may transport antibiotic-resistant bacteria or resistance genes from other places along the migration route to the environment around Qinghai Lake. The antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes, as well as their potential transportation between the environment and the migratory birds under such a unique geographical background were seldom reported.

In this present study, the antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes existing in the environment and the migratory birds around Qinghai Lake were investigated via culture-based analyses of bacterial antibiotic resistance, quantitative PCR of resistance genes and metagenomic sequencing of environmental DNA samples (Supplementary Fig. S1). The aim of this study is to explore the possibility and extent of bacterial antibiotic resistance transmission through migratory birds in the wild environment such as Qinghai Lake watershed. The genetic linkages among different antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), between ARGs and biocide/metal resistance genes (BMRGs), and between resistance genes (ARGs or BMRGs) and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) were evaluated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sampling

Sampling efforts were carried out at 8 sites around Qinghai Lake in June 2017 (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). It was in the early middle stage of the breeding season by when most of the migratory birds using Qinghai Lake as breeding ground had been back in the place. The sampling specimen includes water, soil/sands and bird feces. Water samples were collected in sterile 1-L bottles. Beach soil/sands were collected from the foreshore using a trowel. Multiple soil/sand samples were collected within a half-meter-radius circle, pooled, and stored in the brand-new self-sealing bags. Fresh droppings of migratory birds were collected in autoclaved 50-mL Falcon tubes. Detailed information for the sampling efforts is summarized in Table S1. In total, we collected 26 bird feces, 18 water samples and 24 sand/soil samples. Among the 26 bird feces samples, 18 were from bar-headed geese (Anser indicus, AI), 2 were from great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo, PC), 2 were from great black-headed gulls (Larus ichthyaetus, LI) and one was from ruddy shelducks (Tadorna ferruginea, TF). We strictly distinguished the types of bird feces during the sampling. It is worth noting that some of the feces samples may be contributed by multiple birds from the same kind. Therefore, the actual number of birds that contributed to the collected feces samples should exceed 26. We also collected feces of local ruminants, including 3 sheep (SH) feces and 3 yak (Bos grunniens, BG) feces. Among the 18 feces samples from bar-headed geese, three (B2-3, B3-2 and B8-1, refer to Table S2) were somehow in smaller size. We designated these three goose feces samples as type A (AIA) and the other 15 samples as type B (AIB). The details information and experimental treatment for all samples are summarized in Table S2.

2.2. E. coli isolation

E. coli strains were isolated from environmental and bird feces samples with the previously reported method (Cui et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2018). Briefly, solid samples (soil or feces) were extracted bacterial cells with sterile distilled water. The extracts or the water samples were filtered through sterile 0.45 μm S-Pak® membranes (Millipore, Billerica, United States) after proper dilution. To ensure the uniform distribution of bacteria on the membrane, extra sterile distilled water was added before exerting the vacuum to evenly disperse the bacterial cells. The bacterial-cell-bearing membranes were transferred onto membrane-Thermotolerant E. coli (mTEC) agar to selectively grow E. coli (EPA, 2002). Presumptive E. coli colonies were authenticated by indole–methyl red–Voges–Proskauer–citrate (IMViC) tests. Verified E. coli strains were stored in glycerol (15%) at −40 °C for the subsequent analysis.

2.3. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 11 antibiotics against the E. coli isolates were determined via a modified broth micro-dilution method as per ISO 20776-1:2006 CLSI using 96-well microtiter plates (CLSI, 2019). Briefly, the overnight cell cultures of E. coli isolates were 103-fold diluted and thereafter used to inoculate the testing 96-well plates containing antibiotics of different concentrations. A flame-sterilized 48-pin replicator was used to accelerate the inoculating operation. The MIC endpoints were determined as the lowest concentration with no visible growth after 20 h of incubation at 37 °C. Duplicate tests were conducted for each antibiotic concentration. Positive and negative controls were conducted in antibiotic-free media to assess the growth of E. coli isolates and sterility of the assay, respectively. Quality control of the procedure was conducted by using the susceptive E. coli ATCC 25922.

The multiple-antibiotic resistance index (MARI) was calculated for each type of sample (Krumperman, 1983; Wu et al., 2018). The antibiotic resistance patterns of the E. coli isolates from different samples were compared via non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS). The MICs of E. coli isolates were log-transformed, z-scaled, and used as input data for NMDS. The NMDS was performed in Matlab_2016Ra (MathWorks, Natick, MA, United States) with the mdscale function (Wu et al., 2018).

2.4. DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from sand/soil (1 g each), bird feces (around 0.5 g each) and filtration retentate of water (from about 300 mL water sample each filtered through GN-6 0.45 μm membranes) with the FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, France), following the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of DNA extract was evaluated by gel electrophoresis.

2.5. Quantification of ARGs and MGEs via qPCR

Selected DNA samples (Supplementary Table S2) were evaluated for the abundances of ARGs and MGEs via qPCR. The 16S rRNA gene was used as reference standard. The abundances of ARGs and MGEs were expressed as the amount ratios of target genes to the reference gene (Wu et al., 2018). Twenty-one genes were chosen for the quantification, which included typical ARGs conferring resistance to the 11 antibiotics we tested in this work, as well as some important MGE sequences (Supplementary Table S3). Each qPCR was operated in triplicate. Calculated abundances of target genes in different samples were visualized in a heatmap. The relative abundances of target genes were log-transformed, z-scaled, and used as input data for heatmap construction in Matlab_2016Ra (MathWorks, Natick, MA, United States).

2.6. High-throughput sequencing and data treatment

DNA extracts of the same sample type were pooled together to make 9 composite DNA samples representing fresh water (FW), salt water (SW), sand/soil (SS), sheep feces (SH), yak feces (BG), bar-headed goose feces A (AIA), bar-headed goose feces B (AIB), great cormorant feces (PC) and great black-headed gull feces (LI), respectively. The DNA sample extracted from the ruddy shelduck feces (TF) did not pass the quality test before sequencing. Therefore, we abandoned to sequence this sample. Metagenomic libraries were generated from 1 μg DNA per sample using TruSeq™ DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, USA), following manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, the DNA sample was sheared ultrasonically to 250–300 base pair fragments, then DNA fragments were end-polished, A-tailed, and ligated with the dual-index adaptors for Illumina sequencing with further PCR amplification. High-throughput sequencing was performed at the Hangzhou Woosen Biotechnology on the Illumina Hiseq 2000 platform using a paired-end (2 × 150) sequencing strategy. The sequence data are publicly accessible in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA589661. The detail of the metagenomic sequencing data is shown in the Supplementary Dataset S1.

We obtained an average of around 10.5 Gb (giga bases) of metagenomic data for each DNA sample, resulting in a total of 94.3 Gb sequencing data. The raw reads were quality filtered via Sickle (https://github.com/najoshi/sickle). We used SeqPrep (https://github.com/jstjohn/SeqPrep) to merge paired-end Illumina reads that are overlapping into a single longer read. Clean reads from each sample were assembled with SOAPdenovo software (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/, Version 1.06) (Li et al., 2008). Assembled contigs longer than 500 bp were used for the prediction of open reading frames (ORFs) utilizing MetaGene (http://metagene.cb.k.u-tokyo.ac.jp/) (Noguchi et al., 2006), and a non-redundant ORF set was obtained by using CD-HIT software (http://www.bioinformatics.org/cd-hit/) with thresholds of identity and coverage at 95% and 90%, respectively (Li and Godzik, 2006). Finally, clean reads were mapped back (with an identity >95%) to the non-redundant ORF set using SOAPaligner (http://soap.genomics.org.cn/) to calculate the gene abundance for each sample (Li et al., 2008).

Subsequently, the non-redundant ORF set was analyzed by BLASTx against the Non-redundant protein sequences (NR) database with E-value ≤1 × 10−5 (Altschul et al., 1997). The taxonomic annotations were obtained from the taxonomic information in related to the NR database, and the relative species abundance is calculated using the sum of the corresponding gene abundances of the species. The ORFs were also compared against the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database with E-value ≤1 × 10−5 for analyzing the metabolic function of the bacterial community.

2.7. Annotation and quantification of ARGs, BMRGs and MGEs

In order to analyze the abundance of ARGs, BMRGs and MGEs in the sequencing samples, we downloaded several related databases from relevant websites and constructed local databases for BLAST searching. The non-redundant ORF set was searched for ARGs against the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD, https://card.mcmaster.ca) using BLASTP with E-value ≤1 × 10−5 (McArthur et al., 2013). A query sequence was annotated as an ARG-like fragment if it had ≥80% amino acid identity with the subject sequence in the CARD and the alignment length ≥25 amino acids. To investigate the BMRGs, the ORF set was compared against the BacMet database (http://bacmet.biomedicine.gu.se) using BLASTP with E-value ≤1 × 10−5 (Pal et al., 2014). Similarly, the amino acid identity and alignment length thresholds were set as 80% and 25 amino acids, respectively. To determine the MGEs, the ORF set was matched against the databases of ACLAME (plasmids, pro-phages and viruses, http://aclame.ulb.ac.be) (Leplae et al., 2004), INTEGRALL (integrons, http://integrall.bio.ua.pt) (Moura et al., 2009) and ISfinder (inserting sequences, https://www-is.biotoul.fr) with the similar method. When encountering multiple hits in the database, we just kept the subject sequence with the highest identity (score).

The abundance of an annotated ARG, BMRG or gene related to a MGE in a DNA sample was calculated according to the following equation (Li et al., 2015).

| (1) |

where n is the number of reference sequences of the same ARG, BMRG or gene related to a MGE; N mapped reads is the number of reads in one metagenome sample mapped a reference sequence, L reference sequence the length of the reference sequence; N 16S sequence is the reads number of the 16S sequence identified from the same metagenome sample. L 16S sequence is the average length of 16S sequences, which was calculated to be 1445 bp from sequences of Greengenes database.

2.8. Co-localization analysis

In order to evaluate the horizontal transfer potential of resistance genes (ARGs or BMRGs), we introduced the concept of mobility incidence (Ju et al., 2019), which calculated the probability of co-localization of a resistance gene with MGEs (mobility incidence of the resistance gene). However, in our case, the definition of mobility incidence is slightly different. For individual metagenome sample, the mobility incidence (M%) of an ARG/BMRG is defined as the ratio of detection rate (reads number) of the ARG/BMRG co-localized with at least one MGE on the same contig/scaffold against the total detection rate (reads number) of all ARGs/BMRGs from the same metagenome sample. For an individual ARG/BMRG, the mobility incidence (M%) is the ratio of detection rate of the ARG/BMRG co-localized with at least one MGE on the same contig/scaffold against the total detection rate (reads number) of the same ARG/BMRG among all metagenome samples. To evaluate the co-selection potential between different ARGs or between ARGs and BMRGs, we adopted the similar tactics, i.e. calculating the probability (incidence) of co-localization among different ARGs or between ARGs and BMRGs.

2.9. Network analysis

Network analysis was used to visualize the association between ARGs and bacterial community. This would explore the preferred gene types of co-selection events in the environment. A correlation matrix was constructed by calculating all possible pairwise Spearman's rank correlations (ρ) among ARGs and bacterial genera (Li et al., 2015). Only connections with a strong (Spearman's ρ > 0.8) and significant (P value <0.01) correlation were retained for network analysis. Correlation coefficient and P value were calculated and filtered with RStudio using package Psych (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych). Finally, Gephi (v0.9.2) was used for network visualization, analysis and parameter calculation (Bastian et al., 2009).

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial antibiotic resistance

Totally, 723 E. coli strains were isolated from the collected samples (Supplementary Table S2). 75 isolates were recovered from soil/sand (SS), 93 from fresh water (FW), 60 from the ruddy shelduck feces (TF), 60 from great cormorant feces (PC), 60 from great black-headed gull feces (LI), 80 from bar-headed goose feces of type A (AIA), 115 from bar-headed goose feces of type B (AIB), 90 from sheep feces (SH) and 90 from yak feces (BG). The bacterial antibiotic resistance patterns and levels of different samples are exhibited in Fig. 1 and Table 1 . The highest level of bacterial antibiotic resistance occurs in migratory birds, especially the bar-headed geese (Table 1, AIA and AIB with MARIs of 0.181 and 0.127, respectively) and great black-headed gulls (LI, MARI = 0.144). One E. coli isolate from the feces of bar-headed geese is even resistant to 10 antibiotics (Fig. 1). The bacterial antibiotic resistance pattern varies among different migratory birds. The E. coli isolates from the feces of bar-headed geese show high resistance rate against beta-lactams (cefalexin and ceftriaxone), colistin, and quinolones (ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid), while isolates from cormorant feces exhibit the highest resistance against ampicillin (Table 1). The differentiated antibiotic resistance patterns of these resistant E. coli strains indicate that these resistant isolates are unlikely to be duplicate strains of the same E. coli clone. The bird feces samples with lower bacterial antibiotic resistance are from great cormorants (PC, MARI = 0.074) and ruddy shelducks (TF, MARI = 0.059). The fresh water also gives high bacterial antibiotic resistance (MARI = 0.140). The bacterial antibiotic resistance in local soil/sand (FW, MARI = 0.052) and ruminants (sheep and yaks, MARI = 0.004 and 0.002, respectively) are low. We did not recover any E. coli from salt-water samples except for three isolates from W8-1. Most of the soil/sand (SS) E. coli (96%) were isolated from the soil/sand samples collected at sampling site 3. Most of the fresh water (FW) E. coli isolates (75%) were recovered from the freshwater samples collected at sampling sites 3 (n = 36) and 4 (n = 34).

Fig. 1.

Antibiotic resistance phenotype of E. coli isolates. NMDS analysis reflects the antibiotic resistance pattern of the E. coli isolates recovered from different samples. Red points indicate the E. coli isolated from soil/sand samples. Green ones indicate the isolates from fresh water. Magenta ones are for the isolates from migratory birds and the yellow ones for isolates from local ruminants. The Kruskal stress is 0.1489. A contour map of multidrug resistance (MDR) of the E. coli isolates is generated via interpolating the MDR data of these strains and lined behind the NMDS plot (Wu et al., 2018). The numbers on the contour lines are the numbers of antibiotics that one strain is resistant to. The degree of the MDR is indicated by a color bar with warm color (yellow) representing high level of MDR and cool color (blue) for low MDR degree. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 1.

Resistance percentage and MARI of E. coli isolates from different samples.

| Sample type (Number of isolates) |

AIA (n = 80) |

AIB (n = 115) |

LI (n = 60) |

PC (n = 60) |

TF (n = 93) |

BG (n = 90) |

SH (n = 90) |

FW (n = 93) |

SS (n = 75) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Nalidixic acid | 47.5 | 14.8 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 40.0 | 0 | 0 | 41.9 | 17.3 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 40.0 | 37.4 | 48.3 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 0 | 2.2 | 29.0 | 10.7 | |

| Ampicillin | 3.8 | 36.5 | 33.3 | 50.0 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 20.4 | 2.7 | |

| Tetracycline | 15.0 | 14.8 | 33.3 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 0 | 24.7 | 18.7 | |

| Cefalexin | 52.5 | 9.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ceftriaxone | 11.3 | 9.6 | 18.3 | 0 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 0 | 15.1 | 1.3 | |

| Colistin | 17.5 | 11.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gentamicin | 5.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.8 | 2.7 | |

| Streptomycin | 2.5 | 6.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.4 | 4.0 | |

| Kanamycin A | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.2 | 0 | |

| Amikacin | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 0 | |

| MARI | 0.181 | 0.127 | 0.144 | 0.074 | 0.059 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.140 | 0.052 | |

3.2. Abundance of ARGs and MGE sequences determined via qPCR

The relative abundance of ARGs and MGE sequences in environmental samples determined via qPCR is exhibited as a clustered heatmap (Fig. 2 ). Among the 21 tested genes, 12 are detected the highest relative abundance in bird feces samples, 5 are detected the second highest relative abundance in bird feces samples. Some ARGs conferring resistance against the same type of antibiotics are clustered together, such as the resistance genes against tetracycline (tetW, tetO and tetL), the resistance genes against fluoroquinolone (qnrA and qnrS) and the resistance genes against beta-lactamase genes (bla NMD-1 and bla CTX-M-14) etc.

Fig. 2.

The heatmap of the qPCR determined abundance (log-transformed) of ARGs and MGEs among different samples. The legend for the heatmap denotes corresponding log-transformed values of the abundances of these genes. Genes (rows) were clustered based on Euclidean distance.

3.3. Bacterial community profile

Taxonomic annotation of the metagenomic sequencing data against the NR database indicates that the bacteria are the dominant domain, accounting for >96% of the DNA sequencing reads. Among them,Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are the major constituents, averagely accounting for 57.9%, 15.9% and 7.6% of the bacterial community (Supplementary Fig. S4) respectively, followed by Actinobacteria (3.6%), Verrucomicrobia (3.3%) and Planctomycetes (2.6%). Proteobacteria is the dominant bacterial phylum in the feces of various migratory birds. Its relative abundances in the feces of great cormorants (PC), bar-headed geese A (AIA), great black-headed gulls (LI) and bar-headed geese B (AIB) are 96.0%, 89.3%, 87.2% and 71.9%, respectively. A considerable proportion of Planctomycetes is detected in fresh (14.9%) and salt (7.1%) water. The rumen-specific microbe (Fibrobacteres) of ruminants is detected in the feces of sheep (13.3%) and yaks (0.76%). The hierarchical cluster analysis demonstrates that the bacterial communities in the feces of migratory birds are similar among different avian species and are obviously different from other environmental bacterial community. Fresh water, salt water and soil/sand samples are clustered together for their similar structure of bacterial community. The feces samples of sheep and yaks are also grouped together.

The metabolic functions of the metagenome in different samples were obtained by annotating the metagenomic sequences against the KEGG database. The hierarchical cluster analysis of the environmental samples based on the composition of metabolic modules of their bacterial communities also gives similar mode of clustering (Supplementary Fig. S5).

The samples AIA and AIB shared high similarity in both bacterial community structure and metabolic module composition. Accordingly, we believe that these two types of samples can be regarded as the same one, although the appearance of the two samples is somehow different.

3.4. Abundances of ARGs and BMRGs

According to the criteria of the BLAST searching (identity >80%, E-value ≤1 × 10−5), 115 major ARGs (with relative abundance >10−4 in at least one sample) were annotated among 9 metagenome samples. Most of these ARGs are detected in the feces of migratory birds (n = 105) and local ruminants (n = 61) (Fig. 3A), while ruminants and migratory birds share 53 ARGs. The ARGs detected in the feces of migratory birds are mainly from bar-headed geese (AIA and AIB) and great black-headed gulls (LI) (Fig. 3B). Based on the annotation results of metagenomic data, we calculated the abundances of ARGs, BMRGs and MGEs in all metagenome samples. Feces samples of migratory birds show relatively higher ARG abundance (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Dataset S2). Bar-headed geese have the highest ARG abundance, followed by great black-headed gulls (LI) and great cormorants (PC). Although ruminants share a large portion of ARGs with migratory birds (n = 53), the abundance of these ARGs in ruminants is much lower than that in migratory birds (Fig. 3D). The lowest abundance of ARGs occurs in soil/sand (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Dataset S2). Most ARGs are of the class Drug Efflux (n = 63), representing three types of classic multidrug efflux pumps: resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND)-type (n = 34), major facilitator superfamily (MFS)-type (n = 23) and ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-type (n = 6), followed by the resistance genes against beta-lactam (n = 17, Fig. 3D and Supplementary Dataset S3). The abundance of ARGs in different sample types derived from metagenomic sequencing data is in good accordance with their bacterial antibiotic resistance. The only exception is the fresh water. The E. coli isolates from fresh water exhibit high antibiotic resistance with MARI of 0.140, while the ARG abundance in the metagenome sample of FW is low. We noticed that the freshwater E. coli isolates were mostly recovered from the water samples collected at sites 3 and 4. Site 3 is the active location of migratory birds, while site 4 is the estuary of Heima River. The estuary of Heima River is near the town of Heima River where the river may suffer from anthropogenic impacts. When we performed the metagenomic sequencing, we pooled the DNA samples from W1-1, W1-2, W3-3, W4-1, W4-2, and W5-1 together as a composite sample of FW. We also recovered E. coli isolates from freshwater samples W1-1 (n = 13) and W5-1 (n = 7). Only one of the 20 isolates showed multi-drug resistance. Therefore, the high rate of antibiotic resistance among the fresh-water isolates is believed to be the result of sampling bias.

Fig. 3.

Antibiotic resistance genotype of nine composited metagenome samples. Venn diagrams exhibit the number of shared and unique ARGs among different metagenome samples (A and B). Panel (A) indicates the distribution of ARGs among all metagenome samples. Panel (B) indicates the distribution of ARGs among the metagenome samples of different migratory birds. The relative abundances of ARG types among different samples are shown in panel (C). The insertion diagram enlarges the detail for four samples with low abundance of ARGs. In detailed relative abundances of ARGs (calculated with Eq. (1)) among different samples are exhibited in panel (D). MLS: Macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin.

BMRGs are a class of stress resistance genes that are most likely to form co-selection effects with ARGs. Due to the situations called “cross-resistance” (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012), i.e. the same gene conferring resistance to both antibiotic and metal, a lot of entries in the BacMet database are duplicated with those in the CARD database. We filtered the results and only kept the unique items in BacMet. The abundance of BMRGs among the metagenome samples is positively correlated with the abundance of ARGs (Fig. S6). The highest abundance is detected in AIB, followed by AIA and LI (Supplementary Dataset S4). The lowest abundance of BMRGs also occurred in soil/sand (SS). Most metal resistance genes are of the type Multimetal (n = 33). Thirty-seven kinds of biocide resistance genes are detected among all metagenome samples. The resistance genes against specific metals such as copper (Cu, n = 9), arsenic (As, n = 7), zinc (Zn, n = 5), mercury (Hg, n = 3), nickel (Ni, n = 3), aluminum (Al, n = 2), chromium (Cr, n = 2) and tellurium (Te, n = 1) are also detected (Supplementary Fig. S7 and Dataset S5). Only two cases are confirmed for the co-localization of BMRGs and ARGs on the same contig/scaffold (Supplementary Table S4).

3.5. Mobility potential of ARGs and BMRGs

The abundance of MGEs among the metagenome samples is out of our expectation. The highest abundances of plasmid, IS and integron all occur in the sample of SW (Supplementary Fig. S8). Some cases for co-localization of ARGs and MGE sequences on the same contig/scaffold are listed in Supplementary Table S5. Different from the abundance distribution of MGEs, the co-localization of ARGs and MGEs was mainly detected in the migratory birds and ruminants. According to the calculated mobility incidences (M%), the horizontal transfer potential of various resistance genes in migratory birds is the highest, followed by that in the local ruminants (Supplementary Fig. S9A and B). The lowest horizontal transfer potential of resistance genes occur in those local environment samples (salt water, fresh water and soil/sand samples). The horizontal transfer potential of each resistance gene type is shown in Supplementary Fig. S9C and D (C for ARGs and D for BMRGs).

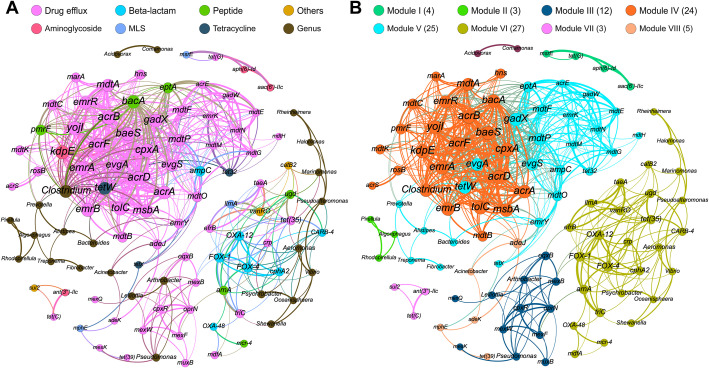

3.6. Co-occurrence patterns of ARGs and bacterial genera

The co-occurrence network derived from the strong (ρ > 0.8) and significant (P < 0.01) correlations among bacterial genera and ARGs are exhibited in Fig. 4 . The network consists of 106 nodes and 612 edges. ARGs of the same type exhibit high co-occurrence rate (Fig. 4A). Some bacterial genera (such as Clostridium) are closely related to ARGs (Fig. 4A). The correlations between bacterial genera and ARGs are summarized in Table S6. Based on the algorithm of fast unfolding of communities in large network, the entire network can be clustered into 9 major modules with modularity index of 0.478 (Blondel et al., 2008). Three main modules occupied 76 out of 105 nodes and 548 out of 612 edges (Fig. 4B). The most densely connected node is defined as the hub of a module, which can act as the indicator of the module (Li et al., 2015). Its abundance reflects the abundances of other co-occurring ARGs in the same module (Supplementary Fig. S10). The hub and co-occurring ARGs of the three main modules are listed in Supplementary Table S7.

Fig. 4.

The network revealing the co-occurrence patterns among ARGs and bacterial genera. In the graph, each colored dot represents a kind of ARG or bacterial genera. The nodes are colored according to their types (A) or to their modularity classes (B). The size of each node is proportional to the number of its connections (degree). Each line (edge) represents the co-occurrence of two objects. Edge width is proportional to Spearman's ρ value. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

The level of bacterial antibiotic resistance is found to be higher in every aspect of this study (phenotype, genotype, the number of ARG types and the relative abundance of ARGs) in some specific migratory birds (bar-headed geese and great black-headed gulls, i.e. AI and LI) than that in the surrounding environment around Qinghai Lake. Notably, there are some inconsistencies among the drug-resistance phenotype of E. coli isolates, qPCR quantitative results of resistance genes and metagenomic sequencing data. Three possible reasons may explain these inconsistencies. First, we only recovered E. coli isolates from a few samples and analyzed their resistance phenotype. The antibiotic resistance of specific bacteria may not fully reflect the overall resistance of the whole bacterial community. In addition, the bacterial antibiotic resistance in individual samples (such as the freshwater samples of site 3) is not universal, which may not reflect the common characteristics of the same kind of samples. Therefore, great care should be taken when interpreting the phenotypic data of bacterial antibiotic resistance, especially for the fecal samples of migratory birds with small number, such as the fecal sample of ruddy shelduck, from which the antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli isolated is weak. It cannot rule out the possibility of individuals with high bacterial antibiotic resistance. Second, the variety of resistance genes we selected for qPCR quantification is very limited, which may not fully reflect the level of bacterial antibiotic resistance in each sample. Third, although the method of metagenomic sequencing can obtain the most comprehensive information about the bacterial antibiotic resistance in the sample, we might ignore the possible differences between individual samples of the same type due to the fact that we mixed the DNA extracts of the same sample type for metagenomic sequencing. Furthermore, the analysis of the metagenomic data depends on the relevant database, in our case the CARD. As we know, the database includes a lot of nontransferable nonspecific drug-efflux genes that may be just involved in some detoxification process (Martinez et al., 2009). However, based on the results from this study, we can still draw the conclusion that the migratory birds are one of the main sources for the bacterial antibiotic resistance in the environment of Qinghai Lake. The abundance of ARGs or movable ARGs is still the highest in migratory birds without considering those drug-efflux genes (Supplementary Fig. S11).

Most of ARGs (58 out of 61) detected in ruminants are also detected in migratory birds (Fig. 3A), and the relative abundance of these shared ARGs is mostly higher in migratory birds (Fig. 3D). The shared ARGs between migratory birds and local ruminants (Fig. 4A) may be due to their sharing the same fresh water resources (Supplementary Fig. S3G), while the disparity in the abundance of ARGs among the species may reflect the transmission direction of ARGs: mostly from migratory birds to ruminants. The types and abundance of ARGs in different species of migratory birds should be related to their feeding habits and migration routes. Bar-headed geese and ruddy shelducks are herbivorous. Great cormorants prey on fish. While greater black-headed gulls utilize multiple food resources. As regarding the migration route, bar-headed geese are considered one of the highest-flying birds. Their migration includes crossing a broad front of the Himalayas and covers the wide area between India and Mongolia along the Central Asian Flyway (Takekawa et al., 2009). Great black-headed gulls and ruddy shelducks breeding in Qinghai Lake migrate to the coast of the Bay of Bengal to overwinter (Chu et al., 2008; Muzaffar et al., 2008; Takekawa et al., 2013). Both India and Bangladesh have suffered heavily from the contamination of bacterial antibiotic resistance (Kakkar et al., 2017; Ahmed et al., 2019). High levels of antibiotic resistance have been detected in wild birds (gulls, Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus) in these areas (Hasan et al., 2014). This may explain why these migratory birds carry significantly higher level of bacterial antibiotic resistance than the local environment around Qinghai Lake. Great cormorants give low degree of bacterial antibiotic resistance and accordingly low abundance of ARGs, which may be because of their special migratory habit and migration route. Unfortunately, no detailed information is available for the migration of the great cormorants around Qinghai Lake. We also observed various migratory birds gathering to share fresh water sources (Supplementary Fig. S3E and G). Therefore, antibiotic-resistant bacteria or resistance genes may be exchanged among migratory birds of various species. Our results confirmed that migratory birds of different species shared 10 common ARGs (Fig. 3B). Usually, ARGs shared among different environmental compartments are believed to exhibit more mobility (with higher mobility incidences). However, according to the mobility analysis of ARGs in this work, it is not the case. Procrustes analysis demonstrates close correlations between the composition of shared bacterial community and the contents of shared ARGs among different environmental compartments (Supplementary Fig. S12), which indicates that the transfer of ARGs in the environment of low selective pressure is mainly through the exchange of resistant bacteria.

In the co-occurring network analysis, the abundance of the hub gene of each module reflects the abundance of co-occurring ARGs of the same module, and indicates the origin of ARGs in the module (Supplementary Fig. S10). We can derive that the ARGs of module IV mainly originate from bar-headed geese B (AIB, Supplementary Fig. S10A). The ARGs of module V mainly originate from local ruminants (sheep and yaks, Supplementary Fig. S10B). The ARGs of module VI most likely originate from multiple migratory birds (Supplementary Fig. S10C): bar-headed geese (AIA, AIB), great black-headed gulls (LI) and great cormorants (PC). As we have incorporated the bacterial genera into the network analysis, it is interesting that the bacterial genera of the ruminant-originated module V include typical gut bacteria: Prevotella, Bacteroides and Fibrobacter. Prevotella is related to diet of more carbohydrates, especially fiber (Wu et al., 2011). Fibrobacter is the major rumen bacteria (Montgomery et al., 1988). The bacterial genera in the migratory-birds-originated module VI mostly are halophilic (Halomonas), osmotolerant and psychrophilic (Psychrobacter), which is related to the characteristics of local environment and climate. Some genera are typical marine or aquatic bacteria such as Vibrio, Marinomonas, Rheinheimera (Zhong et al., 2014), Oceanisphaera and Shewanella (Satomi et al., 2003). It is reasonable to detect marine bacteria in the feces-droppings of aquatic birds inhabiting around the saltwater lake. There are two possible reasons for the formation of modular structure in the co-occurrence network of ARGs. First, some ARGs are related to specific bacterial genera, which present in the bacterial communities in relation to specific environmental conditions (Li et al., 2015). Modules IV and V, which consist of many ARGs of the type of Drug efflux, are more likely to be in this situation. Some of the bacterial genera of these two modules are possible hosts of ARGs. More attention should be paid to the bacterial genus Clostridium of module IV, one of the main bacterial genera of gut microbial community in bar-headed geese (Wang et al., 2017). It is closely related to multiple ARGs (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Table S6). Members of this genus were associated with waterborne diseases and were used as fecal indicator (Skanavis and Yanko, 2001). The favorable germination and growth of the species, Clostridium difficile, in gut microbiome have been associated with antibiotic treatment (Theriot et al., 2014). Second, the situations of co-resistance, i.e. ARGs responsible for the resistance against two or more antibiotics are adjacent to each other on one MGE (Seiler and Berendonk, 2012), present in the bacterial communities that have experienced special multi-antibiotic selective pressure, may result in the enrichment of these ARGs. Module VI containing ARGs against specific antibiotics such as beta-lactam, glycopeptide and phenicol etc. should be of this situation. The clustering of ARGs was often discovered in the environment under heavy anthropogenic impacts, via the method of quantitative PCR (Johnson et al., 2016) and metagenomic sequencing (Li et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2019). We detected the co-localization of some ARGs with high co-occurrence rate (with incidence of 35.8%) on the same contigs/scaffolds (Table S8). Most of the co-localized ARGs are of the same module in the co-occurrence network. Quite some of these co-localized ARGs encode subunits of the same efflux pump. The co-localization of ARGs conferring resistance to different antibiotics is also observed, such as the colocalized ARGs conferring resistance to tetracycline (tet(G)) and aminoglycoside (aph(6)-Id). Therefore, the strong statistical correlation between resistant genes is determined by their actual physical linkage at the DNA molecular level. Co-selection will occur between genetically linked ARGs (Johnson et al., 2016). There are only several cases (with low incidence of 3.7%) that metal resistance genes and ARGs are located on the same contigs/scaffolds (Supplementary Table S4), indicating low probability of co-selection between two kinds of resistance genes. This finding is consistent with the previously reported metagenomic sequencing results (Ju et al., 2019). However, as mentioned in the previous report, the limited assembly length of sequencing data may underestimate the co-selection potential if there are large gaps between these genes.

According to the calculated mobility incidences for ARGs (Supplementary Fig. S9A), the horizontal transfer potential of ARGs is much higher in migratory birds (accounting for 96.0% of sequencing reads of MGE-linked ARGs) than in local environment. Considering that the relative abundance of ARGs is much lower in the environment than in migratory birds, the abundance of movable ARGs in local environment is very low. Therefore, the movable ARGs seem to be still confined to the bacterial community in migratory birds, which indicates that a large-scale horizontal transfer of ARGs has not yet formed in the environment around Qinghai Lake. On the other hand, the relative abundance of ARGs in the migratory birds (AIA and LI in Fig. 3D) is one to two orders of magnitude lower than that ever reported in the poultry (chicken) (Li et al., 2015). The level of bacterial antibiotic resistance in the environment around Qinghai Lake is further lower (SW, FW and SS in Fig. 3D). The overall anthropogenic influence on this environment is weak. Based on our study, although the migratory birds are a major source of environmental ARGs around Qinghai Lake, their impact on the overall bacterial antibiotic resistance in the surrounding environment is limited.

In the part of environment around Qinghai Lake where is less affected by human activities, the role of migratory birds in the environmental dissemination of antibiotic resistance is more like a “hidden danger”. They do bring foreign antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes to local environment. Although the impact is limited, we can imagine that once appropriate selective pressure is imposed (such as the selective pressure against the hub genes), the co-selection effect between different ARGs will rapidly deteriorate the situation. These foreign ARGs will spread out within a short period of time due to their high potential of horizontal transfer. Because of the numerous numbers and the wide range of activities, the migratory birds need much more attention to their roles in mediating the transportation of environmental antibiotic resistance.

5. Conclusions

According to our systematic study on the bacterial antibiotic resistance of migratory birds around Qinghai Lake and the environment of their habitat, the migratory birds do carry foreign ARGs during their migration and become a major source of bacterial antibiotic resistance in the local environment. Although its impact on the receptor environment is still limited, the specific genetic properties (high co-selection and mobility potential of these ARGs) of the antibiotic resistance determinants that the migratory birds carry remind us that the role of migratory birds in the environmental dissemination of antibiotic resistance should not be ignored and deserves more attention.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yufei Lin:Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Xiaohong Dong:Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Rui Sun:Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Jiao Wu:Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - review & editing.Lejin Tian:Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing.Dawei Rao:Methodology, Writing - review & editing.Lihua Zhang:Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.Kun Yang:Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank the administration of Qinghai Lake National Natural Reserve for authorizing and assisting the collection of bird droppings samples. We thank the financial supports from the Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21677104) and the Initiating Research Fund for Talent Introduction of Sichuan University (No. YJ201355). Finally, the author (Kun Yang) would like to express his sincere thanks to his longtime friend, Dr. Zheng Yang. He is always willing to provide selfless help for the English editing of our articles. It is delightful to share the research progress and results with Zheng. At this special time of global pandemic, the author (K.Y.) hopes that Zheng and his family are all well throughout the epidemic situation of COVID-19.

Editor: Fang Wang

Footnotes

Supporting information. Information for the sampling efforts and experimental treatments (Tables S1 and S2), information of primer pairs for qPCR (Table S3), linkages between ARGs and BMRGs (Table S4) and between ARGs and MGEs (Table S5), correlations between bacterial genera and ARGs (Table S6), compositions of three main modules in the co-occurring network (Table S7), Contigs/scaffolds with multiple ARGs (Table S8); diagram illustrating the study route (Fig. S1), illustration of the sampling effort (Fig. S2), photos taken during sampling (Fig. S3), composition (Fig. S4) and metabolic subsystems (Fig. S5) of bacterial communities, abundance of BMRGs (Figs. S6 and S7), abundance and percentage of MGEs (Fig. S8), horizontal transfer potential of resistance genes (Fig. S9), Abundance of module hubs and the co-occurring ARGs (Fig. S10), relative abundance of ARGs without considering drug-efflux genes (Fig. S11), relationship between shared ARGs and shared bacterial community (Fig. S12). File type: Microsoft Word .docx file.

Datasets. Information of metagenomic datasets (Dataset S1), abundance of ARG types (Dataset S2), abundance of ARGs (Dataset S3), abundance of BMRG types (Dataset S4), and abundance of BMRGs (Dataset S5). File type: Microsoft Excel .xlsx file. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139758.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Tables and Figures

Supplementary Datasets

References

- Ahmed I., Rabbi M.B., Sultana S. Antibiotic resistance in Bangladesh: a systematic review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;80:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atterby C., Ramey A.M., Hall G.G., Jarhult J., Borjesson S., Bonnedahl J. Increased prevalence of antibiotic-resistant E. coli in gulls sampled in Southcentral Alaska is associated with urban environments. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2016;6:32334. doi: 10.3402/iee.v6.32334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian M., Heymann S., Jacomy M. International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media: San Jose, California. 2009. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. [Google Scholar]

- Berendonk T.U., Manaia C.M., Merlin C., Fatta-Kassinos D., Cytryn E., Walsh F. Tackling antibiotic resistance: the environmental framework. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;13(5):310–317. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondel V.D., Guillaume J.L., Lambiotte R., Lefebvre E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008 doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/p10008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Chen R., Jing L., Bai X., Teng Y. A metagenomic analysis framework for characterization of antibiotic resistomes in river environment: application to an urban river in Beijing. Environ. Pollut. 2019;245:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu G.Z., Hou Y.Q., Zhang G.G., Liu D.P., Dai M., Jiang H.X. Satellite tracking of the migration routes of the waterbirds breeding in Qinghai Lake. Chin. J. Nat. 2008;30(2):84–89. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI . CLSI; Wayne, PA, USA: 2019. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing—Twenty-Ninth Edition: M100. [Google Scholar]

- Cristobal-Azkarate J., Dunn J.C., Day J.M., Amabile-Cuevas C.F. Resistance to antibiotics of clinical relevance in the fecal microbiota of Mexican wildlife. PLoS One. 2014;9(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H., Yang K., Pagaling E., Yan T. Spatial and temporal variation in enterococcal abundance and its relationship to the microbial community in Hawaii beach sand and water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79(12):3601–3609. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00135-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EPA., U.S. Office of Water, U.S. EPA; Washington, DC: 2002. Method 1103.1: Escherichia coli (E. coli) in Water by Membrane Filtration Using Membrane-Thermotolerant Escherichia coli Agar (mTEC) [Google Scholar]

- Guenther S., Aschenbrenner K., Stamm I., Bethe A., Semmler T., Stubbe A. Comparable high rates of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in birds of prey from Germany and Mongolia. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan B., Melhus A., Sandegren L., Alam M., Olsen B. The gull (Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus) as an environmental bioindicator and reservoir for antibiotic resistance on the coastlines of the Bay of Bengal. Microb. Drug Resist. 2014;20(5):466–471. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernando-Amado S., Coque T.M., Baquero F., Martinez J.L. Defining and combating antibiotic resistance from One Health and Global Health perspectives. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4(9):1432–1442. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0503-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T.A., Stedtfeld R.D., Wang Q., Cole J.R., Hashsham S.A., Looft T. Clusters of antibiotic resistance genes enriched together stay together in swine agriculture. MBio. 2016;7(2):e02214–e02215. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02214-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju F., Beck K., Yin X.L., Maccagnan A., McArdell C.S., Singer H.P. Wastewater treatment plant resistomes are shaped by bacterial composition, genetic exchange, and upregulated expression in the effluent microbiomes. ISME J. 2019;13(2):346–360. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0277-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar M., Walia K., Vong S., Chatterjee P., Sharma A. Antibiotic resistance and its containment in India. BMJ. 2017;358:j2687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp C.W., Dolfing J., Ehlert P.A., Graham D.W. Evidence of increasing antibiotic resistance gene abundances in archived soils since 1940. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44(2):580–587. doi: 10.1021/es901221x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumperman P.H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983;46(1):165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00399869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leplae R., Hebrant A., Wodak S.J., Toussaint A. ACLAME: a CLAssification of mobile genetic elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D45–D49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Li Y., Kristiansen K., Wang J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2008;24(5):713–714. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Yang Y., Ma L., Ju F., Guo F., Tiedje J.M. Metagenomic and network analysis reveal wide distribution and co-occurrence of environmental antibiotic resistance genes. ISME J. 2015;9(11):2490–2502. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liakopoulos A., Mevius D.J., Olsen B., Bonnedahl J. The colistin resistance mcr-1 gene is going wild. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016;71(8):2335–2336. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Dong X., Wu J., Rao D., Zhang L., Faraj Y. Metadata analysis of mcr-1-bearing plasmids inspired by the sequencing evidence for horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes between polluted river and wild birds. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:352. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Xiao H., Lei F., Zhu Q., Qin K., Zhang X.W. Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus infection in migratory birds. Science. 2005;309(5738):1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1115273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelino V.R., Wille M., Hurt A.C., Gonzalez-Acuna D., Klaassen M., Schlub T.E. Meta-transcriptomics reveals a diverse antibiotic resistance gene pool in avian microbiomes. BMC Biol. 2019;17(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12915-019-0649-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J.L., Sanchez M.B., Martinez-Solano L., Hernandez A., Garmendia L., Fajardo A. Functional role of bacterial multidrug efflux pumps in microbial natural ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009;33(2):430–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur A.G., Waglechner N., Nizam F., Yan A., Azad M.A., Baylay A.J. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57(7):3348–3357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00419-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohsin M., Raza S., Roschanski N., Schaufler K., Guenther S. First description of plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in a wild migratory bird from Asia. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2016;48(4):463–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery L., Flesher B., Stahl D. Transfer of Bacteroides succinogenes (Hungate) to Fibrobacter gen. nov. as Fibrobacter succinogenes comb. nov. and description of Fibrobacter intestinalis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1988;38(4):430–435. doi: 10.1099/00207713-38-4-430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moura A., Soares M., Pereira C., Leitao N., Henriques I., Correia A. INTEGRALL: a database and search engine for integrons, integrases and gene cassettes. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1096–1098. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzaffar S.B., Takekawa Prosser D.J.J.Y., Douglas D.C., Yan B., Xing Z. Seasonal movements and migration of Pallas’s Gulls Larus ichthyaetus from Qinghai Lake, China. Forktail. 2008;24(24):100–107. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.49.4.292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi H., Park J., Takagi T. MetaGene: prokaryotic gene finding from environmental genome shotgun sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(19):5623–5630. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normile D. Avian influenza. Evidence points to migratory birds in H5N1 spread. Science. 2006;311(5765):1225. doi: 10.1126/science.311.5765.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen B., Munster V.J., Wallensten A., Waldenstrom J., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Global patterns of influenza a virus in wild birds. Science. 2006;312(5772):384–388. doi: 10.1126/science.1122438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal C., Bengtsson-Palme J., Rensing C., Kristiansson E., Larsson D.G. BacMet: antibacterial biocide and metal resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D737–D743. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey A.M., Hernandez J., Tyrlov V., Uher-Koch B.D., Schmutz J.A., Atterby C. Antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli in migratory birds inhabiting remote Alaska. Ecohealth. 2018;15(1):72–81. doi: 10.1007/s10393-017-1302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satomi M., Oikawa H., Yano Y. Shewanella marinintestina sp. nov., Shewanella schlegeliana sp. nov. and Shewanella sairae sp. nov., novel eicosapentaenoic-acid-producing marine bacteria isolated from sea-animal intestines. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003;53(Pt 2):491–499. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler C., Berendonk T.U. Heavy metal driven co-selection of antibiotic resistance in soil and water bodies impacted by agriculture and aquaculture. Front. Microbiol. 2012;3:399. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skanavis C., Yanko W.A. Clostridium perfringens as a potential indicator for the presence of sewage solids in marine sediments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2001;42(1):31–35. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(00)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa J.Y., Heath S.R., Douglas D.C., Perry W.M., Javed S., Newman S.H. Geographic variation in Bar-headed Geese Anser indicus: connectivity of wintering areas and breeding grounds across a broad front. Wildfowl. 2009;59(2009):100–123. [Google Scholar]

- Takekawa J.Y., Prosser D.J., Collins B.M., Douglas D.C., Perry W.M., Yan B. Movements of wild ruddy shelducks in the central Asian flyway and their spatial relationship to outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1. Viruses. 2013;5(9):2129–2152. doi: 10.3390/v5092129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theriot C.M., Koenigsknecht M.J., Carlson P.E., Jr., Hatton G.E., Nelson A.M., Li B. Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3114. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel T.P., Brower C., Gilbert M., Grenfell B.T., Levin S.A., Robinson T.P. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112(18):5649–5654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Zheng S.S., Sharshov K., Sun H., Yang F., Wang X.L. Metagenomic profiling of gut microbial communities in both wild and artificially reared Bar-headed goose (Anser indicus) Microbiologyopen. 2017;6(2) doi: 10.1002/mbo3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.D., Chen J., Hoffmann C., Bittinger K., Chen Y.Y., Keilbaugh S.A. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334(6052):105–108. doi: 10.1126/science.1208344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Huang Y., Rao D.W., Zhang Y.K., Yang K. Evidence for environmental dissemination of antibiotic resistance mediated by wild birds. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng R., Smith L.M., Prosser D.J., Takekawa J.Y., Newman S.H., Sullivan J.D. Investigating home range, movement pattern, and habitat selection of bar-headed geese during breeding season at Qinghai Lake, China. Animals (Basel) 2018;8(10) doi: 10.3390/ani8100182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z.P., Liu Y., Liu L.Z., Wang F., Zhou Y.G., Liu Z.P. Rheinheimera tuosuensis sp. nov., isolated from a saline lake. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014;64(Pt 4):1142–1148. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.056473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables and Figures

Supplementary Datasets