Abstract

Background

Pressure ulcers (PU), one of the common challenging public health problems affecting patient with spinal cord injury. PUs occurs over bony areas of the body where pressure and tissue distortion is greatest. It has a significant impact to the patient and health care system. Moreover, it has psychological, physical, social burden and decrease the quality of life (QoL) of patients. Despite its serious complications, limited evidence is available on the global magnitude of pressure ulcers among patient with spinal cord injury. Hence, this review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the global magnitude of pressure ulcers among patient with spinal cord injury.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, African Journals Online, PsycINFO, and Web of Science were systematically searched to retrieve related articles. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline was followed. DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was applied to obtain the pooled effect size. To investigate heterogeneity across the included studies, I2 test was employed. Publication bias was examined using funnel plot and Egger’s regression test statistic. Sensitivity analysis was deployed to see the effect of a single study on the overall estimation. Analysis was done using STATA™ Version 14 software.

Results

A total of 24 studies which comprises of 600,078 participants were included in this study. The global pooled magnitude of pressure ulcers among patients with spinal cord injury was 32.36% (95% CI (28.21, 36.51%)). Based on the subgroup analysis, the highest magnitude of pressure ulcer was observed in Africa 41.19% (95% CI: 31.70, 52.18).

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that about one in three patients with spinal cord injury had pressure ulcers. This implies that the overall global magnitude of pressure ulcer is relatively high. Therefore, policy maker and other concerned body should be design country context- specific preventive strategies to reduce the burden of pressure ulcers in patients with spinal cord injury.

Keywords: Pressure ulcers, Spinal cord injury, Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Ethiopia

Background

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a life-threatening and debilitating injury with tremendous immediate and long-term extensive impact on the medical, social, psychological and economic aspects of clients, their caregivers and the society [1–3]. The annual incidence rate of SCI is 44 cases per 1, 000, 000 people in Tehran [4], and 5.5 to 195.4 cases per million in European countries [5]. Spinal cord injured patients have a high risk of developing pressure ulcers due to motor and sensory impairments, immobility, changes in skin composition, and prolonged hospital stays [6, 7]. PUs are a serious, costly, and life-long complication of SCI. Around, 30–40% of clients with spinal cord injuries develop pressure ulcers during the acute and rehabilitation phases [8].

Pressure ulcer and its treatment is one of the most challenging clinical problems in hospitals specially among patients with spinal cord injury [9]. Even though several pressure ulcer classification systems are available, National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) is the commonest method. According to the NPUAP consensus development conference, pressure ulcers are classified based on severity from suspected deep tissue injury through unstageable, with suspected deep tissue injury representing the earliest stage of pressure ulcer formation, and unstageable is defined as “full thickness tissue loss in which the base of the ulcer is covered by slough (yellow, tan, gray, green, or brown) and/or eschar (tan, brown, or black) in the wound bed” [10].

Though PU is largely preventable patient safety problems, they have major impacts to the affected individual and on the health care system. It highly affects the psychological, physical, social well-being and the quality of life of the affected individuals [11–13]. Likewise, it leads to recurrent hospitalizations, multiple surgeries, potentially devastating complications, increased costs for patient care, morbidity and early mortality [9, 14, 15]. PU carry a significant economic burden, with treatment costs of a PU far exceeding preventive costs. For example, a study done in Canada, revealed that the total monthly cost for treatment of PU among SCI was 18,758 USD [3]. Pressure ulcer may account for 25% of the overall cost of treating paraplegic and tetraplegic persons [16]. Moreover, a study done in Canada showed average monthly cost for treatment of PU in patients with SCI was $4745 [17].

Large differences have been reported on the magnitude of PUs patients with SCI in different studies. For instance, it varying from 11 to 50% in the current publications [6, 18]. Similarly, a study done in Switzerland reported that the incidence of PU was 2.31 per patient-year [18]. Poor pressure relief practices lead to PU development in persons with SCI [10]. Management and care of PU has become a serious public health challenge, with longer hospital stays than for other causes. Preventive measures to decrease the development of PUs consisted of basic skin care, pressure dispersion using fenestrated foams and alternating weight-bearing sites by regular frequent positioning [7]. In addition, the key targets for interventions has been advocated to reduce the burden of pressure ulcers in patient with SCI. These interventions includes identification of risk factors, patient education, acute intensive care, and support body surfaces [19].

The etiology of PUs is complex and rooted in multiple risk factors. Studies suggest that risk factors for PU in patient with SCI include duration after SCI (> 1 year) [20], age (older age), sex (being male) [20, 21], poor nutritional status [22], quadriplegia [23–25], smoking [6, 26], comorbidity [23, 27], severe Braden scores [28], weight (being underweight) [26], lower level of education [20, 21], and lack of an intimate partner [21] were some of the risk factors associated with PU. Similarly, it has been reported that patients with higher-level spinal cord injuries are more susceptible than those with lower-level lesions [13]. Hence, identification of risk factors used as benchmarks to design appropriate prevention measure, to improve client safety and efficient utilization of resources.

PUs among SCI clients remains unrelenting problem and a major issue in nursing care across the globe. Prevention of PU is a key role of nurses, and is considered a quality indicator of nursing care [29]. Thought most previous studies have been conducted, to assess the magnitude of PU in acute care setting, intensive care unit, and on public hospitals; however the global magnitude of PU among patient with SCI remains unknown. Hence, this study aimed to estimate the global burden of PU among spinal cord injured patients. Findings from the current study could be serve as benchmark for institutional health care policy-makers to implement appropriate preventive measures to reduce and prevent PU. In addition, it will assist clinicians in estimating burden of PU as part of an overall quality indicator for facilities and an assessment of the effectiveness prevention strategies.

Methods

Search strategy and database

A two-step search strategy was used to identify all relevant literature. First, six electronic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, Africa Journals Online, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycINFO were systematically searched. Second, a manual search of grey literatures was performed to identify additional relevant research to augment our meta-analysis. All electronic sources of information were searched for the period of January 1, 2000 to July 2, 2019. The search was conducted using the following terms and phrases: “pressure ulcer”, “pressure injury”, “decubitus ulcer”, “spinal cord injury”, and “prevalence”. Boolean operators like “AND” and “OR” were used to combine search terms.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) All observational studies which report the prevalence PU among SCI; (2) articles published in peer reviewed journals and grey literature:(3) published in the English language between 2000 to 2019; (4) we imposed no restriction on the area where it is conducted; and (5) the group of patients admitted without PUs. Studies were excluded on any one of the following conditions: (1) Patients admitted with PU; (2) they have poor quality score as per the stated criteria; and (3) articles in which fail to estimate the outcome (PU).

Selection and quality assessment

Data were extracted by three authors using a pre-piloted and standardized data extraction format prepared in a Microsoft excel. For each included study, the following data were extracted: the name(s) of the author (‘s), year of publication, study area, study design, sample size, prevalence, data collection year, and data collection methods. The quality of each included study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS). Articles were included in the analysis if they scored ≥7 out of 10 points in three domains of the equally weighted modified NOS components for a cohort studies [30], (Additional file 1). In addition, for cross-sectional studies quality assessment tool, score of ≥5 out of 10 considered as high quality score [31], (Additional file 2). On the other hand, to assess the risk of bias within studies tools developed for observational studies by Hoy and colleagues was used [32]. The tool has ten items to assess the risk of bias (i.e. external validity has four items and internal validity has six items). Based on these items the overall risk of study bias could be summary as low risk of bias, moderate risk of bias, and high risk of bias. The quality score of each study were extracted from each incorporated article by three independent authors. Any disagreements during data extraction were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Statistical analysis

To obtain the meta-weighted burden of pressure ulcer among SCI, a meta-analysis using random-effects model DerSimonian and Laird method was employed. Cochran’s Q chi-square statistics and I2 statistical test was conducted to assess the random variations between primary studies [33]. In case of high heterogeneity, subgroup analysis to reduce heterogeneity, and meta regression analysis to explore sources of heterogeneity were utilized. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of a funnel plot and objectively using the Egger bias test [34, 35]. Sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate whether the pooled effect size was influenced by individual studies. The data were analysed using STATA™ Version 14 statistical software [36].

Data synthesis and reporting

The results of this review were reported based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was followed [37]. Moreover, results were presented using forest plots and summary tables.

Result

Search results

We found a total of 1053 articles. Of these, 1027 studies were found from PubMed (611), Scopus (171), PsycINFO (10), Google Scholar (76), Web of Science (92), and Africa Journals Online (67). In addition, the remaining 26 were retrieved through manual search. Of these, 529 articles were excluded due to duplication. Following the removal of duplicate studies, the titles and abstracts were evaluated, and 407 studies were excluded after reading of titles and abstracts base on the pre-specified inclusion criteria. Then, a total 117 full text articles were assessed for their eligibility based on the pre-set inclusion criteria. After reviewing the full text, based on the pre-defined criteria and quality assessment, 24 articles were included for the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart diagram of the study selection

Baseline characteristic of the included studies

A total of 24 studies with 600,078 study participants were included to estimate the pooled prevalence of PU among SCI patients. In this meta-analysis, various countries were represented across a globe: 8 of studies were from America [6, 38–43], 7 from Europe [18, 23, 44–48], 5 from Asia [20, 28, 49–51], and 4 from Africa [7, 22, 24, 52]. The highest prevalence of PU (56%) was reported from Europe [44], whereas the lowest prevalence (11%) was reported in a study conducted in America [6]. With respect to sample size, the number of study participants varied from 38 to 7489. The quality score of each primary study, based on the Newcastle- Ottawa quality score assessment, was moderate to high for all 24 articles assessed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demonstrates the baseline characteristic of primary studies

| First Author | Pub. year | study country, continent | study design | sample size | Prevalence% (95%CI) |

Data Collection year |

data collection methods | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ash, D etal [44] | 2002 | United Kingdom, Europe | Cross-sectional | 144 | 56(47.9,64.1) | 1998 to 2000 | document review | 7 |

| Brienza,D., et al. [38] | 2017 | United States, North America | cohort | 104 | 37.5(28.2,46.8) | 2008–2012 | observation and examination | 7 |

| Chopra,T.,et al. [53] | 2016 | United States, North America | Cross-sectional | 201 | 38(31.3,44.7) | January 2004 and December 2008 | document review | 7 |

| DeJong, G., et al. [39] | 2014 | United states, north America | Cohort | 159 | 13.1(7.8,18.3) | NA | Document review | 7 |

| Eslami V et al. [20] | 2012 | Iran, Asia | Cross-sectional | 7489 | 34.6(33.5,35.7) | June 2007 to June 2009 | physical examination | 9 |

| Fazel FS, etal [28] | 2018 | Iran,Asia | cohort | 580 | 28.1(24.4,31.7) | June 2013 to December 2015 | Observation and examination | 8 |

| Garber, S.L., et al. [40] | 2000 | United states, North America | Cohort | 118 | 31(22.2,39.3) | NA | Interview and exam | 8 |

| Haisma, J.A., et al. [45] | 2007 | Netherlands,Europe | cohort | 212 | 36(29.5,42.5) | May 2000 and September 2003 | Self-report | 8 |

| Idowu, O., et al. [22] | 2011 | Nigeria,Africa | cohort | 105 | 45.9(36.4,55.4) | 1 October 2004 and 30November 2006 | Skin examination | 8 |

| Iyun A.O. etal [7] | 2012 | Nigeria, Africa | cohort | 67 | 47.7(35.7,59.7) | January 2003 to June 2004 | Self-report and documentation | 7 |

| Joseph, C. and L.N. Wikmar [24] | 2015 | south Africa,Africa | cohort | 141 | 29.8(22.2,37.4) | 15 September 2013 to 14 September 2014 | observation and examination | 8 |

| Kovindha, A. et al. [49] | 2015 | Thailand, Asia | Cross-sectional | 129 | 26.4(18.8,34) | 1 January 2013 to 31December 2013 | Self-report | 7 |

| Krishnan,S., et al. [41] | 2017 | United States, North America | Cross-sectional | 3098 | 20.3(18.9,21.7) | 1993 to 2006 | document review | 8 |

| Li,C., et al. [6] | 2016 | United States,North America | Cross-sectional | 350 | 11(7.6,14.4) | August 2011 to February 2014 | Self-report | 8 |

| Löfvenmark I et al. [52] | 2016 | Botswana,Africa | cohort | 38 | 48(32.1,63.9) | 1February 2011 to 31January 2013 | Skin examination | 8 |

| Raghavan, P., et al., [46] | 2003 | United kingdom, Europe | Cross-sectional | 472 | 23(19.2,26.8) | NA | Observation and exam | 7 |

| Richard-Denis, A., et al. [42] | 2016 | Canada,North America | Cohort | 123 | 33.3(24.9,41.6) | January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2011 | Document review | 7 |

| Saunders et al. [43] | 2013 | United States, North America | Cross-sectional | 2549 | 19.9(18,21.7) | NA | mail-in survey | 9 |

| Scheel-Sailer, A., et al. [47] | 2013 | Switzerland,Europe | cohort | 185 | 25.4(19.1,31.7) | 1 September 2009 to 28February 2010 | observation and examination | 7 |

| Sheerin, F. etal [48] | 2005 | Ireland, Europe | Cross-sectional | 82 | 37(26.5,47.4) | December 2000 to December 2002 | document review | 7 |

| Taghipoor, K.D., et al. [51] | 2009 | Iran, Asia | Cross-sectional | 3791 | 39.1(37.5,40.6) | NA | Document review | 7 |

| Tchvaloon,E., et al. [50] | 2007 | Israel, Asia | cohort | 143 | 26.6(19.4,33.8) | 1962 and 2004 | document review | 7 |

| van der Wielen H et al. [18] | 2016 | Switzerland,Europe | cohort | 185 | 50(42.8,57.2) | September 2009 to February 2010 | observation | 7 |

| Verschueren J et al. [23] | 2011 | Netherlands, Europe | cohort | 193 | 36.5(29.7,43.3) | NA | observation and examination | 8 |

N/A not applicable

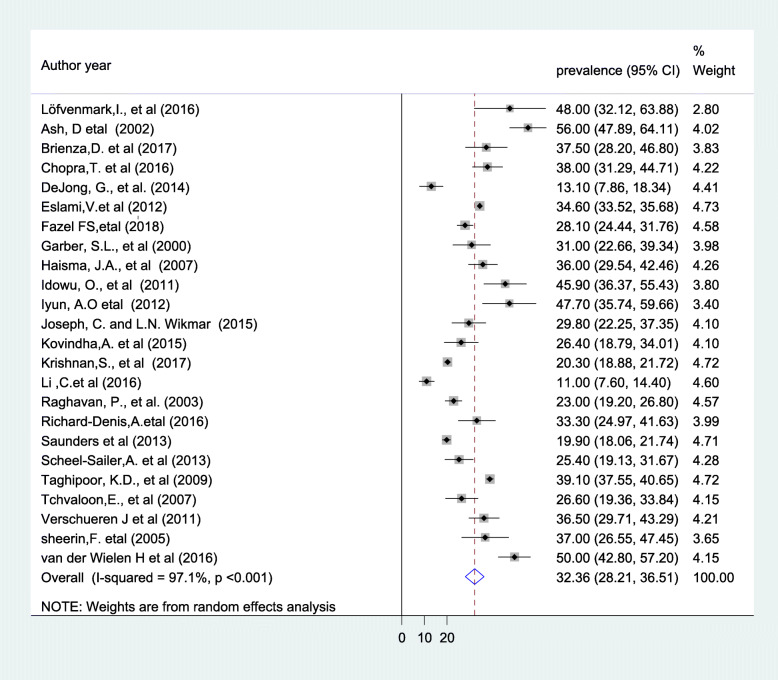

Global burden of pressure ulcer among patients with spinal cord injury

The finding of current meta-analysis using a random effects model indicated that the global pooled magnitude of PU in patients with SCI was found to be 32.36% (95% CI: 28.21–36.51), (Fig. 2) with a substantial level of heterogeneity (I2 = 97.1%; P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

The global pooled prevalence of PU in patients with SCI

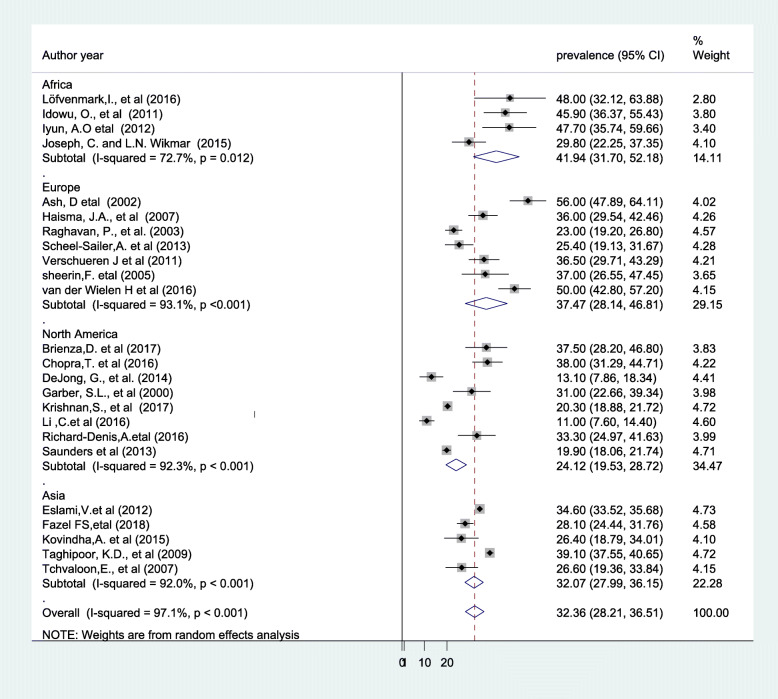

Sub-group analysis

The presence of significant heterogeneity among the primary studies requires the need to conduct subgroup analysis. As a result, the finding of subgroup analysis using study design showed that the highest magnitude of pressure ulcer was observed among study done using cohort design which was 34.85% (95% CI: 28.50, 41.19), I2 = 88.4%) (Fig. 3). Concerning with study continent, high magnitude of pressure ulcers was observed among study done in Africa which was 41.94%(95% CI: 31.70, 52.18), I2 = 72.7%) of our included primary studies, (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing subgroup analysis by study design

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing subgroup analysis by study continent

Meta- regression analysis

In the present review, we conducted meta-regression analysis by considering year of publication, and sample size as covariates of interest to identify the possible sources of random variations across primary studies. But, the result of the meta-regression analysis showed that both covariates were not statistically significant source of heterogeneity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Meta regression analysis for the included studies to identify source of heterogeneity

| Covariate (source) | Coefficient | Standard error | P-value | 95% Conf. Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication year | −0.416 | 0.530 | 0.442 | − 1.526, 0.694 |

| Sample size | 0.0002 | 0.001 | 0.869 | −0.003, 0.0035 |

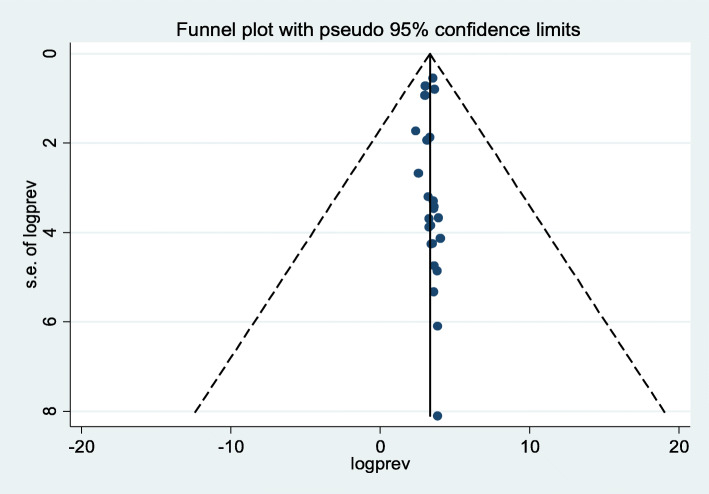

Publication bias

To identify the presence of publication bias funnel plot, and Egger’s regression test were performed. Therefore, we obtained that there was no publication bias among the included studies, as illustrated by the symmetrical distribution of a funnel plot (Fig. 5). Likewise, Egger’s regression test results, showed that there was no statistically significant publication bias across the included studies as evidenced by (P = 0.74).

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot to test the presence of publication bias of the 24 studies

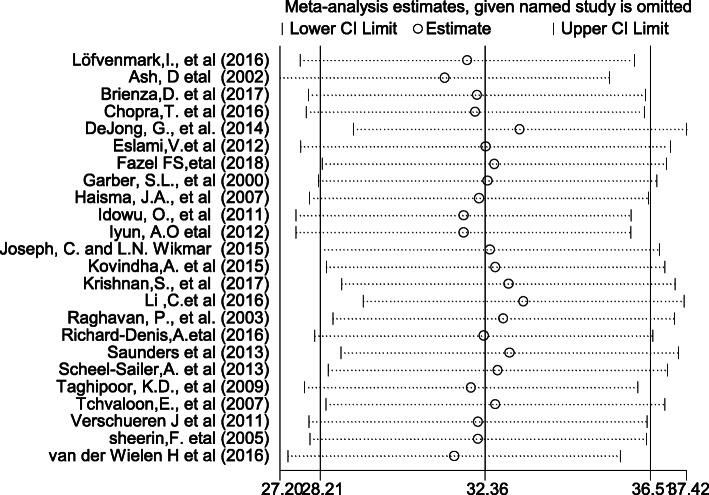

Sensitivity analysis

The finding of sensitivity analysis using random effects model revealed that no single study affected the overall magnitude of pressure ulcer among SCI (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Result of sensitivity analysis of the 24 studies

Discussion

The current meta-analysis provided up-to-date knowledge on the magnitude of PU among spinal cord injured patients. The present findings revealed that the global pooled prevalence of PU in patients with SCI was 32.36% (95% CI: 28.21, 36.51%). This finding is much higher than a meta-analysis study done on global prevalence of PU in public hospitals at14.8% [54]. This indicated that PU is highly prevalent among patients with spinal cord injury, and reflect an inadequately prevention and management of PU risk factors.

The result of the subgroup analysis based on study design (cross-sectional vs cohort) showed that the highest pooled prevalence of PU was observed from those studies with cohort design 34.85% (95%CI: 28.50, 41.19). This variation might be in case of cohort design the outcome variable was obtained through observation, skin assessment, physical examination, and with certain follow up time, whereas in cross-sectional studies data were collected with document review and self-report. Therefore, these situations may contribute for variation across study designs. Similarly, the result of subgroup analysis based on continent revealed that the highest magnitude of PU was reported in Africa 41.94%, followed by Europe 37.47%. The possible explanations for this variation might be due methodological differences, variation in quality of care, differences in health seeking behavior between the populations, policy and strategy difference [9, 55].

This study has clinical implications in that the increase burden of PU in SCI patients should alarm policy makers and clinician to enhance patient awareness on the impact of PU, to adhere preventive measures, to improve patient safety, to minimize treatment cost, and to design treatment strategies for PU among patients with SCI. In addition, the finding serves as a bench mark to health care professional to provide a attention on the application of standardized care, and represents a marker of quality of care.

The current review and meta-analysis has some limitations: First, inclusion of English only articles, when this was international based review; Second, this study do not identify the predictors of pressure ulcers among patients with spinal cord injury; Third, it may not be representative of the entire content, as no data were found form all of the globe; and fourth, all included studies were reported hospital-based data.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that about one in three patients with spinal cord injury had pressure ulcers. This implies that the overall global magnitude of pressure ulcer is relatively high. Therefore, policy makers and other concerned body should be design country context specific effective preventive strategies to decrease the burden of PU among patients with SCI, and to improve the overall quality of healthcare service at large. Furthermore, further research is needed to identify associated factors for the development of PU among patient with SCI.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Methodological quality assessment of cohort studies using modified Newcastle - Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Additional file 2. Methodological quality assessment of cross-sectional studies using modified Newcastle - Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence Interval

- NPUAP

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel

- PU

Pressure Ulcer

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SCI

Spinal Cord Injury

Authors’ contributions

WSS and TYA developed the protocol and involved in the design, selection of study, data extraction, and statistical analysis and developing the initial drafts of the manuscript. YAA, HM and TYA involved in data extraction, quality assessment, statistical analysis and revising. WSS and YAA prepared the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data analyzed during the current meta-analysis is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12891-020-03369-0.

References

- 1.Jang Y, Wang Y-H, Wang J-D. Return to work after spinal cord injury in Taiwan: the contribution of functional independence. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(4):681–686. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumont RJ, Okonkwo DO, Verma S, Hurlbert RJ, Boulos PT, Ellegala DB, Dumont AS. Acute spinal cord injury, part I: pathophysiologic mechanisms. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2001;24(5):254–264. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White BA, Dea N, Street JT, Cheng CL, Rivers CS, Attabib N, Kwon BK, Fisher CG, Dvorak MF. The economic burden of urinary tract infection and pressure ulceration in acute traumatic spinal cord injury admissions: evidence for comparative economics and decision analytics from a matched case-control study. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34(20):2892–2900. doi: 10.1089/neu.2016.4934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rahimi-Movaghar V, Moradi-Lakeh M, Rasouli MR, Vaccaro AR. Burden of spinal cord injury in Tehran, Iran. Spinal Cord. 2010;48(6):492. doi: 10.1038/sc.2009.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jazayeri SB, Beygi S, Shokraneh F, Hagen EM, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury worldwide: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(5):905–918. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C, DiPiro N, Cao Y, Szlachcic Y, Krause J. The association between metabolic syndrome and pressure ulcers among individuals living with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2016;54(11):967. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyun AO, Malomo AO, Oluwatosin OM, Ademola SA, Shokunbi MT. Pattern of presentation of pressure ulcers in traumatic spinal cord injured patients in university college hospital, Ibadan. Int Wound J. 2012;9(2):206–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathew A, Samuelkamaleshkumar S, Radhika S, Elango A. Engagement in occupational activities and pressure ulcer development in rehabilitated south Indian persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51(2):150. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kruger EA, Pires M, Ngann Y, Sterling M, Rubayi S. Comprehensive management of pressure ulcers in spinal cord injury: current concepts and future trends. J Spinal Cord Med. 2013;36(6):572–585. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black J, Baharestani MM, Cuddigan J, Dorner B, Edsberg L, Langemo D, Posthauer ME, Ratliff C, Taler G. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel's updated pressure ulcer staging system. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20(5):269–274. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000269314.23015.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaisas S, Pyatak EA, Blanche E, Blanchard J, Clark F. Lifestyle changes and pressure ulcer prevention in adults with spinal cord injury in the pressure ulcer prevention study lifestyle intervention. Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69(1):6901290020p6901290021–6901290020p6901290010. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2015.012021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorecki C, Brown JM, Nelson EA, Briggs M, Schoonhoven L, Dealey C, Defloor T, Nixon J, group EQoLPUP Impact of pressure ulcers on quality of life in older patients: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1175–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lala D, Dumont FS, Leblond J, Houghton PE, Noreau L. Impact of pressure ulcers on individuals living with a spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(12):2312–2319. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause JS, Saunders LL. Health, secondary conditions, and life expectancy after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(11):1770–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krause JS, Zhai Y, Saunders LL, Carter RE. Risk of mortality after spinal cord injury: an 8-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(10):1708–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Fort M, Espagnacq M, Albert T, Lefèvre C, Perrouin-Verbe B, Ravaud J-F. Risk of pressure ulcers in tetraplegic people: a French survey crossing regional experience with a long-term follow-up. Eur J Pub Health. 2018;28(6):993–999. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan BC, Nanwa N, Mittmann N, Bryant D, Coyte PC, Houghton PE. The average cost of pressure ulcer management in a community dwelling spinal cord injury population. Int Wound J. 2013;10(4):431–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Wielen H, Post M, Lay V, Gläsche K, Scheel-Sailer A. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers in spinal cord injured patients: time to occur, time until closure and risk factors. Spinal Cord. 2016;54(9):726. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zakrasek E, Creasey G, Crew J. Pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury in developing nations. Spinal Cord. 2015;53(1):7. doi: 10.1038/sc.2014.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eslami V, Saadat S, Arejan RH, Vaccaro A, Ghodsi S, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2012;50(12):899. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, DeVivo MJ, Jackson AB. Pressure ulcer prevalence in people with spinal cord injury: age-period-duration effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(6):1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Idowu O, Yinusa W, Gbadegesin S, Adebule G. Risk factors for pressure ulceration in a resource constrained spinal injury service. Spinal Cord. 2011;49(5):643. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verschueren J, Post M, De Groot S, Van der Woude L, Van Asbeck F, Rol M. Occurrence and predictors of pressure ulcers during primary in-patient spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2011;49(1):106. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joseph C, Wikmar LN. Prevalence of secondary medical complications and risk factors for pressure ulcers after traumatic spinal cord injury during acute care in South Africa. Spinal Cord. 2016;54(7):535. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correa G, Fuentes M, Gonzalez X, Cumsille F, Pineros J, Finkelstein J. Predictive factors for pressure ulcers in the ambulatory stage of spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord. 2006;44(12):734. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krause JS, Vines CL, Farley TL, Sniezek J, Coker J. An exploratory study of pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: relationship to protective behaviors and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(1):107–113. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.18050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gould LJ, Olney CM, Nichols JS, Block AR, Simon RM, Guihan M. Spinal cord injury survey to determine pressure ulcer vulnerability in the outpatient population. Med Hypotheses. 2014;83(5):552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2014.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fazel FS, Derakhshanrad N, Yekaninejad MS, Vosoughi F, Derakhshanrad A, Saberi H. Predictive value of Braden risk factors in pressure ulcers of outpatients with spinal cord injury. Acta Medica Iranica. 2018;56:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL, et al. Risk assessment scales for pressure ulcer prevention: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(1):94–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McPheeters ML, Kripalani S, Peterson NB, Idowu RT, Jerome RN, Potter SA, Andrews JC. Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): Quality-assessed Reviews. UK: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2012. Quality improvement interventions to address health disparities: closing the quality gap-revisiting the state of the science. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Modesti PA, Reboldi G, Cappuccio FP, Agyemang C, Remuzzi G, Rapi S, Perruolo E, Parati G, Settings EWGoCRiLR Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, Baker P, Smith E, Buchbinder R. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman D. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context: Wiley; 2008.

- 35.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter J. Arcsine test for publication bias in meta-analyses with binary outcomes. Stat Med. 2008;27(5):746–763. doi: 10.1002/sim.2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.StataCorp L. Stata statistical software (version release 14) College Station: Author; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brienza D, Krishnan S, Karg P, Sowa G, Allegretti A. Predictors of pressure ulcer incidence following traumatic spinal cord injury: a secondary analysis of a prospective longitudinal study. Spinal Cord. 2018;56(1):28. doi: 10.1038/sc.2017.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeJong G, Hsieh C-HJ, Brown P, Smout RJ, Horn SD, Ballard P, Bouchard T. Factors associated with pressure ulcer risk in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(11):971–986. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garber SL, Rintala DH, Hart KA, Fuhrer MJ. Pressure ulcer risk in spinal cord injury: predictors of ulcer status over 3 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(4):465–471. doi: 10.1053/mr.2000.3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishnan S, Karg PE, Boninger ML, Brienza DM. Association between presence of pneumonia and pressure ulcer formation following traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40(4):415–422. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2016.1180099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richard-Denis A, Thompson C, Bourassa-Moreau É, Parent S, Mac-Thiong J-M. Does the acute care spinal cord injury setting predict the occurrence of pressure ulcers at arrival to intensive rehabilitation centers? Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;95(4):300–308. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saunders LL, Krause JS, Acuna J. Association of race, socioeconomic status, and health care access with pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(6):972–977. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ash D. An exploration of the occurrence of pressure ulcers in a British spinal injuries unit. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(4):470–478. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haisma JA, Van Der Woude LH, Stam HJ, Bergen MP, Sluis TA, Post MW, Bussmann JB. Complications following spinal cord injury: occurrence and risk factors in a longitudinal study during and after inpatient rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(5):393–398. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raghavan P, Raza W, Ahmed Y, Chamberlain M. Prevalence of pressure sores in a community sample of spinal injury patients. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17(8):879–884. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr692oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheel-Sailer A, Wyss A, Boldt C, Post M, Lay V. Prevalence, location, grade of pressure ulcers and association with specific patient characteristics in adult spinal cord injury patients during the hospital stay: a prospective cohort study. Spinal Cord. 2013;51(11):828. doi: 10.1038/sc.2013.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheerin F, Gillick A, Doyle B. Pressure ulcers and spinal-cord injury: incidence among admissions to the Irish national specialist unit. J Wound Care. 2005;14(3):112–115. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2005.14.3.26750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kovindha A, Kammuang-Lue P, Prakongsai P, Wongphan T. Prevalence of pressure ulcers in Thai wheelchair users with chronic spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2015;53(10):767. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tchvaloon E, Front L, Gelernter I, Ronen J, Bluvshtein V, Catz A. Survival, neurological recovery and morbidity after spinal cord injuries following road accidents in Israel. Spinal Cord. 2008;46(2):145. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taghipoor KD, Arejan RH, Rasouli MR, Saadat S, Moghadam M, Vaccaro AR, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Factors associated with pressure ulcers in patients with complete or sensory-only preserved spinal cord injury: is there any difference between traumatic and nontraumatic causes? J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11(4):438–444. doi: 10.3171/2009.5.SPINE08896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Löfvenmark I, Wikmar LN, Hasselberg M, Norrbrink C, Hultling C. Outcomes 2 years after traumatic spinal cord injury in Botswana: a follow-up study. Spinal Cord. 2017;55(3):285. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chopra T, Marchaim D, Awali RA, Levine M, SM S, Chalana IK, Ahmed F. Risk factors and acute in-hospital costs for infected pressure ulcers among gunshot-spinal cord injury victims in southea stern Michigan. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(3):315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al Mutairi KB, Hendrie D. Global incidence and prevalence of pressure injuries in public hospitals: a systematic review. Wound Med. 2018;22:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xakellis GC, Jr, Frantz RA, Lewis A, Harvey P. Translating pressure ulcer guidelines into practice: it's harder than it sounds. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14(5):249–258. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Methodological quality assessment of cohort studies using modified Newcastle - Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Additional file 2. Methodological quality assessment of cross-sectional studies using modified Newcastle - Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed during the current meta-analysis is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.