Abstract

Background

The third Sustainable Development Goal aims to ensure healthy lives and to promote well-being for all at all ages. The health system plays a key role in achieving these goals and must have sufficient human resources in order to provide care to the population according to their needs and expectations.

Methods

This paper explores the issues of unemployment, underemployment, and labor wastage in physicians and nurses in Mexico, all of which serve as barriers to achieving universal health coverage. We conducted a descriptive, observational, and longitudinal study to analyze the rates of employment, underemployment, unemployment, and labor wastage during the period 2005–2017 by gender. We used data from the National Occupation and Employment Survey. Calculating the average annual rates (AAR) for the period, we describe trends of the calculated rates. In addition, for 2017, we calculated health workforce densities for each of the 32 Mexican states and estimated the gaps with respect to the threshold of 4.45 health workers per 1000 inhabitants, as proposed in the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health.

Results

The AAR of employed female physicians was lower than men, and the AARs of qualitative underemployment, unemployment, and labor wastage for female physicians are higher than those of men. Female nurses, however, had a higher AAR in employment than male nurses and a lower AAR of qualitative underemployment and unemployment rates. Both female physicians and nurses showed a higher AAR in labor wastage rates than men. The density of health workers per 1000 inhabitants employed in the health sector was 4.20, and the estimated deficit of workers needed to match the threshold proposed in the Global Strategy is 70 161 workers distributed among the 16 states that do not reach the threshold.

Conclusions

We provide evidence of the existence of gender gaps among physicians and nurses in the labor market with evident disadvantages for female physicians, particularly in labor wastage. In addition, our results suggest that the lack of physicians and nurses working in the health sector contributes to the inability to reach the health worker density threshold proposed by the Global Strategy.

Keywords: Gender inequality, Physicians, Nurses, Employment, Labor wastage

Resumen (Spanish)

Antecedentes

El tercer Objetivo de Desarrollo Sostenible busca alcalzar vidas saludables y promover el bienestar para todos en todas las edades. Por lo cual, el sistema de salud es clave para lograr estos objetivos, y debe tener suficientes recursos humanos para brindar atención a la población de acuerdo con sus necesidades y expectativas.

Métodos

Exploramos el desempleo, subempleo y desperdicio laboral en médicos y enfermeras en México como barreras para lograr la Cobertura Universal de Salud. Realizamos un estudio descriptivo, observacional y longitudinal para analizar las tasas de empleo, subempleo, desempleo y desperdicio laboral en el período 2005-2017, por género en ambas profesiones. Utilizamos la Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo. Calculamos tasas anuales promedio (TAP) para el período para describir las tendencias. Además, para 2017 calculamos las densidades de la fuerza laboral para todos los 32 estados, y estimamos sus brechas con respecto al umbral de 4.45 propuesto en la Estrategia Global sobre Recursos Humanos para la Salud.

Resultados

La TAP de las médicas empleadas era más bajo que el de los médicos, y la TAP del subempleo, el desempleo y el despilfarro laboral para las médicas eran más altas que en los hombres. Las enfermeras tienen una TAP más alta en el empleo que los enfermeros y una TAP más baja de subempleo y desempleo. Tanto las médicas como las enfermeras muestran unas TAP más altas en las tasas de desperdicio laboral. La densidad de trabajadores por cada 1,000 habitantes empleados en el sector de la salud fue de 4.2, y el déficit estimado para alcanzar el umbral propuesto en la Estrategia Global es de 70,161 trabajadores. Hipotéticamente, si todos los desempleados, subempleados y aquellos dedicados a las actividades del hogar estuvieran empleados en el sector de la salud, la densidad sería de 7.16.

Conclusiones

Encontramos evidencia sobre la existencia de brechas de género entre médicos y enfermeras en el mercado laboral con desventajas evidentes para las médicas, y particularmente en el desperdicio laboral. Además, mostramos la falta de médicos y enfermeras trabajando en el sector de la salud para alcanzar el umbral propuesto en la Estrategia Global.

Palabras clave: Desigualdad de género, médicos, enfermeras, mercado laboral, desperdicio laboral

Background

The third Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3) aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. To this end, all national governments have been called upon to achieve universal health coverage (UHC), which must include financial risk protection, access to basic quality health care services, and access to safe, effective, quality essential medicines. Consequently, health systems play a key role in achieving these ends, and therefore, they must have an adequate number of available and accessible human resources for health (HRH) to offer a wide variety of services to the population [1–3] and accelerate progress towards UHC [4, 5]. In addition, increases in HRH have been linked to a better quality of health services and increased development of solid and sustainable health systems [6].

The 2016 Human Resources for Health Report highlights the importance of aligning the health workforce with the population’s health needs, service coverage, and health outcomes [2, 7, 8]. Currently, most middle-income countries have a greater health workforce availability than a few years ago [3], which has been shown to positively impact health outcomes [6, 7]. Nevertheless, despite progress in HRH, there are still problems related to shortages of health workers, imbalances in geographical distribution, barriers to inter-professional collaboration, poor working conditions, unequal gender distribution, and limited availability of data regarding health workforce [9, 10].

Globally, we must address the HRH deficit, as well as inequalities in its distribution [11]. These problems with lack of medical personnel are widely recognized as the most insurmountable obstacles to improving health system performance and access to health services, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Besides, the health workforce is changing its gender profile. While there is an increase of women in medicine, an increase in men has been reported in nursing [12]. These phenomena can, in part, be explained by changing gender roles in Western societies.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that in order to achieve the SDGs by 2030 as planned, 18 million more health workers are needed in LMIC [6]. In the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health (GSHRH), the WHO deemed that a density of 4.45 physicians, nurses, and midwives per 1000 inhabitants is the threshold required to achieve UHC [4].

In the Americas, about 70% of countries have enough physicians, nurses, and midwives to provide basic health services, but those countries still face challenges related to distribution, migration, and lack of training [13], especially in rural or high-marginalized areas [14].

In Mexico, in the 1990s, the unemployment rate of physicians was 12% while 8% had a job in a non-medical area [15]. Importantly, inactivity, unemployment, underemployment, and lower wages were concentrated in female physicians [16]. In 2008, 87% of physicians were working in the health sector and 10% had a non-medical job.

In Mexico, there is a great heterogeneity among nurses in terms of levels of training (i.e., technical, professional, and postgraduate) [17], which has contributed to the appearance of inequities in wages, as well as allocation and geographic distribution.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OCDE) [18], Mexico has a density above the threshold of 4.45 proposed in the GSHRH. However, we hypothesized that not all the 32 Mexican states reach the threshold due to unequal distribution throughout the country, and even if there was no unemployment, underemployment, and labor wastage in the health sector, some states of high marginalization would not reach the threshold. In addition, behind this hypothesis, we believe that although the number of professionals has increased over time, a possible cause of labor wastage in the country may be partly because women in both professions have fewer job opportunities and a large percentage of them are dedicated to household activities in a full-time basis.

Methods

Objective

The present study analyzes trends in employment, quantitative and qualitative underemployment, unemployment, and labor wastage rates for both physicians and nurses by gender between 2005 and 2017. Additionally, for 2017, we estimate the gap in the availability of HRH for each of the 32 Mexican states and compare it to the threshold proposed in the GSHRH, 4.45 health workers per 1000 inhabitants. For the second objective, we consider two scenarios: (a) calculating the densities only with the personnel employed in the health sector and (b) calculating the densities considering the entire available health workforce, including health personnel that are employed, unemployed, underemployed, and those dedicated to household activities on a full-time basis.

Study design

We conducted a descriptive, observational, and longitudinal study to estimate the rates of employment, underemployment, unemployment, and labor wastage for both physicians and nurses from 2005 to 2017. For our estimates, we used data from the National Occupation and Employment Survey (ENOE, in Spanish). This survey uses a two-stage sampling, probabilistic design to enhance representativeness at the national and state levels. It is carried out with the objective of collecting information about the occupational characteristics of the Mexican population. The data is used to calculate and release official employment indicators. The units of analysis are households and the population aged 15+. Data is collected every 3 months using a longitudinal design, where, each quarter, 20% of households are replaced, so that each household remains in the sample for five quarters (INEGI) [19]. In order to describe trends, we analyze data from the third quarter (Trim-III) of each year from the period 2005–2017 (excluding each quarter of the remaining sample from the third quarter of the following year, except for 2017 where we take all households). The estimations for the size of the population are based on the projections of the National Population Council (CONAPO, in Spanish) [20] as well as the grouping of the states according to their level of marginalization (i.e., very high, high, medium, low, and very low) [21].

Variables

We estimate the rates of employment, unemployment, underemployment, and labor wastage as well as the average annual rate (AAR) and the average annual growth rate (AAGR) from 2005 to 2017. Our definition of health workforce (HW) includes two occupational categories: physicians and nurses (including technicians) who have completed professional schooling. The following definitions are used to estimate the rates and constitute the employment pattern of the HW [15, 16, 22, 23]:

Employed health workforce (E): physicians and nurses who work 20 h or more per week and perform health care or administrative functions in the health sector.

Unemployed health workforce (U): physicians and nurses who were seeking work at the time of the survey because they were not linked to an economic activity.

Quantitative underemployment (QnU): physicians and nurses whose work are underutilized because they work less than 20 h per week performing functions according to their profession or practice their profession as a secondary occupation.

Qualitative underemployment (QlU): physicians and nurses who work but in a non-medical job.

Household activities (H): physicians and nurses who exclusively perform household activities on a full-time basis.

Potential health workforce (PHW): we included the following groups as potential workforce E, U, QnU, QlU, and H.

Employment, unemployment, underemployment, and labor wastage rates are calculated as follows:

Rate of employment =

Rate of unemployment =

Rate of quantitative underemployment =

Rate of qualitative underemployment =

Rate of labor wastage = ×1000

To summarize and describe the trends in rates over the period 2003–2017, the AAR and AAGR were estimated as follows:

Average annual rate (AAR) =

Average annual growth rate (AAGR) = (where i is the rate of E, U, QnU, QlU, and wastage)

Finally, in order to estimate the gap between the current number of health workers and the 4.45 per 1000 inhabitants threshold recommended in GSHRH, we estimate two measures for health workforce density:

Employed health workforce density (EHWD) =

Potential health workforce density (PHWD) =

Statistical analysis

We performed the analysis on two levels. (1) At the national level, we estimated the rates of employment, quantitative and qualitative underemployment, unemployment, and labor wastage by gender and profession, and their AAR and AAGR from 2005 to 2017. (2) For 2017 and for each profession stratified by gender, we calculated the percentages and CI95% according to the employment pattern, age, schooling, and marital status; chi-square tests for nominal variables and Wilcoxon tests for ordinal variables were performed in order to assess the statistical differences. Further, at the state level, we estimated the percentages of employment and labor wastage for both physicians and nurses; states were grouped according to the level of marginalization, and we calculated the average percentage of each group.

Finally, considering the EHWD and PHWD for each state in Trim III-2017, we estimated the gap between each of these density indicators and the threshold of 4.45 per 1000 inhabitants as recommended in the GSHRH. The analyses were performed using STATA MP 13.0 accounting for the complex survey design, and statistical significance was set to the value P < 0.05.

Results

During the period 2005–2017, the average annual rate (AAR) of employment was 792 per 1000 physicians and the average annual growth rate (AAGR) was 0.22%. Both quantitative and qualitative underemployment rates remained stable with no major changes (AAGR 0.89 and 1.81, respectively), and for every 1000 physicians, on average, 128 had a non-medical job (Table 1). The analysis of employment rates by gender reveals a lower AAR for women than for men (767 vs. 806). Likewise, the AAR and AAGR of qualitative underemployment and unemployment estimations for female physicians were higher than those for men.

Table 1.

Physicians: rates of employment, quantitative and qualitative underemployment, and unemployment, by gender. Mexico 2005–2017

| Rates × 1 000* | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | AAR | AAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All physicians | |||||||||||||||

| N* | 202 421 | 222 017 | 202 619 | 239 011 | 242 738 | 261 089 | 238 299 | 251 861 | 243 903 | 220 122 | 229 035 | 215 676 | 263 538 | ||

| Employment | 797 | 770 | 835 | 809 | 796 | 773 | 787 | 776 | 793 | 809 | 733 | 806 | 806 | 792 | 0.22 |

| Quantitative underemployment | 55 | 76 | 62 | 55 | 66 | 78 | 72 | 70 | 70 | 61 | 67 | 48 | 51 | 64 | 0.98 |

| Qualitative underemployment | 131 | 133 | 97 | 127 | 124 | 117 | 125 | 120 | 130 | 112 | 176 | 138 | 127 | 128 | 1.81 |

| Unemployment | 17 | 21 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 32 | 16 | 34 | 7 | 17 | 24 | 8 | 16 | 17 | 34.49 |

| Women | |||||||||||||||

| N* | 64 624 | 73 314 | 79 531 | 79 875 | 87 532 | 98 042 | 93 623 | 96 338 | 100 171 | 81 358 | 88 736 | 94 496 | 121 128 | ||

| Employment | 785 | 699 | 861 | 788 | 771 | 719 | 743 | 728 | 821 | 762 | 704 | 789 | 797 | 767 | 0.61 |

| Quantitative underemployment | 76 | 89 | 40 | 57 | 53 | 95 | 87 | 58 | 52 | 64 | 61 | 47 | 49 | 64 | 2.09 |

| Qualitative underemployment | 120 | 162 | 94 | 139 | 161 | 113 | 137 | 157 | 119 | 150 | 207 | 154 | 148 | 143 | 6.13 |

| Unemployment | 18 | 49 | 6 | 16 | 16 | 73 | 34 | 57 | 8 | 23 | 29 | 9 | 6 | 26 | 54.55 |

| Men | |||||||||||||||

| N* | 137 797 | 148 703 | 123 088 | 159 136 | 155 206 | 163 047 | 144 676 | 155 523 | 143 732 | 138 764 | 140 299 | 121 180 | 142 410 | ||

| Employment | 802 | 806 | 819 | 819 | 810 | 805 | 815 | 806 | 774 | 836 | 751 | 818 | 813 | 806 | 0.22 |

| Quantitative underemployment | 45 | 69 | 77 | 54 | 74 | 68 | 62 | 78 | 83 | 59 | 71 | 49 | 54 | 65 | 4.80 |

| Qualitative underemployment | 136 | 119 | 99 | 121 | 104 | 119 | 118 | 97 | 137 | 90 | 157 | 126 | 109 | 118 | 1.82 |

| Unemployment | 16 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 19 | 6 | 14 | 22 | 7 | 24 | 12 | 45.37 |

AAR average annual rate, AAGR average annual growth rate

*Professionals dedicated to household activities are not included in this table

Regarding nursing, the calculated AAR revealed that, for every 1000 nurses, there were 701 employed for 20 h or more per week, 43 were employed for fewer than 20 h, 226 held a non-medical job, and 30 were unemployed (Table 2). The analysis by gender showed that even though the employment rate of nurses was higher for women (706) than in men (654), the rate was decreasing for both genders. That said, the decrease is more rapid for men (AAGR = − 0.76%). The AAR and AAGR of qualitative underemployment and unemployment were lower for female nurses.

Table 2.

Nurses: rates of employment, quantitative and qualitative underemployment, and unemployment rates, by gender. Mexico 2005–2017

| Rates × 1 000 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | AAR | AAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All nurses | |||||||||||||||

| N* | 242 615 | 262 686 | 265 191 | 267 477 | 313 070 | 293 819 | 265 734 | 322 045 | 333 749 | 338 678 | 368 520 | 374 248 | 461 377 | ||

| Employment | 689 | 712 | 721 | 716 | 710 | 681 | 668 | 697 | 705 | 723 | 716 | 707 | 664 | 701 | -0.26 |

| Quantitative underemployment | 51 | 37 | 25 | 48 | 51 | 59 | 46 | 40 | 49 | 34 | 42 | 33 | 46 | 43 | 4.16 |

| Qualitative underemployment | 232 | 233 | 225 | 210 | 208 | 209 | 261 | 227 | 226 | 219 | 212 | 222 | 248 | 226 | 0.95 |

| Underemployment | 28 | 18 | 29 | 26 | 30 | 51 | 25 | 36 | 20 | 23 | 29 | 38 | 41 | 30 | 10.76 |

| Women | |||||||||||||||

| N* | 229 379 | 243 848 | 244 208 | 243 485 | 288 128 | 264 242 | 243 441 | 282 406 | 296 571 | 290 456 | 320 630 | 320 293 | 390 397 | ||

| Employment | 684 | 721 | 737 | 716 | 717 | 681 | 664 | 703 | 723 | 729 | 721 | 712 | 674 | 706 | -0.06 |

| Quantitative underemployment | 52 | 35 | 27 | 50 | 55 | 64 | 48 | 45 | 46 | 35 | 43 | 34 | 49 | 45 | 4.18 |

| Qualitative underemployment | 235 | 225 | 207 | 211 | 198 | 201 | 261 | 217 | 212 | 211 | 209 | 223 | 246 | 220 | 0.93 |

| Underemployment | 29 | 19 | 29 | 23 | 30 | 53 | 26 | 34 | 19 | 25 | 27 | 31 | 31 | 29 | 7.95 |

| Men | |||||||||||||||

| N* | 13 236 | 18 838 | 20 983 | 23 992 | 24 942 | 29 577 | 22 293 | 39 639 | 37 178 | 48 222 | 47 890 | 53 955 | 70 980 | ||

| Employment | 767 | 603 | 530 | 715 | 632 | 682 | 706 | 648 | 559 | 689 | 683 | 675 | 610 | 654 | -0.76 |

| Quantitative underemployment | 42 | 65 | 9 | 23 | 3 | 10 | 21 | 4 | 77 | 29 | 38 | 26 | 29 | 29 | 170.96 |

| Qualitative underemployment | 183 | 332 | 436 | 202 | 327 | 274 | 260 | 300 | 333 | 270 | 237 | 219 | 262 | 280 | 8.92 |

| Underemployment | 8 | 0 | 25 | 60 | 39 | 35 | 13 | 47 | 32 | 12 | 42 | 80 | 99 | 38 | 54.17 |

AAR average annual rate, AAGR average annual growth rate

*Professionals dedicated to household activities are not included in this table

Table 3 shows that labor wastage rates in both physicians and nurses were greater for women than for men in almost every year of the 2005–2017 period. In 2005, women represented 35.4% and 95.8% of workforce among physicians and nurses, respectively, whereas in 2017, those percentages were 48.5% and 87.8%, respectively. Nevertheless, the AAR of labor wastage in both female physicians and female nurses is higher than men.

Table 3.

Rates of labor wastage in physicians and nurses, by gender; Mexico

| Rates × 1 000** | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | AAR | AAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians (N) | 216 073 | 235 672 | 219 424 | 255 268 | 262 094 | 284 615 | 264 306 | 266 915 | 264 245 | 241 550 | 246 442 | 234 733 | 292 035 | ||

| Women (%) | 35.4 | 35.0 | 42.1 | 36.9 | 38.8 | 41.3 | 41.7 | 40.6 | 43.4 | 40.9 | 40.8 | 46.4 | 48.5 | ||

| Men (%) | 64.6 | 65.0 | 57.9 | 63.1 | 61.2 | 58.7 | 58.3 | 59.4 | 56.6 | 59.1 | 59.2 | 53.6 | 51.5 | ||

| Physicians (rate) | 253 | 274 | 229 | 243 | 263 | 291 | 291 | 267 | 268 | 263 | 319 | 260 | 273 | 269 | 1.23 |

| Women | 336 | 379 | 258 | 332 | 336 | 400 | 369 | 352 | 282 | 372 | 379 | 315 | 318 | 341 | 1.31 |

| Men | 208 | 218 | 207 | 190 | 217 | 214 | 235 | 210 | 257 | 187 | 278 | 212 | 230 | 220 | 2.64 |

| Nurses (N) | 313 245 | 337 709 | 335 117 | 351 807 | 393 197 | 368 618 | 359 431 | 388 177 | 428 357 | 436 853 | 455 892 | 482 463 | 591 801 | ||

| Women (%) | 95.8 | 94.2 | 93.6 | 93.2 | 93.6 | 91.9 | 93.7 | 89.7 | 91.0 | 88.7 | 89.3 | 88.3 | 87.8 | ||

| Men (%) | 4.2 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 10.3 | 9.0 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 12.2 | ||

| Nurses (rate) | 467 | 446 | 430 | 456 | 435 | 457 | 506 | 422 | 451 | 439 | 421 | 452 | 482 | 451 | 0.57 |

| Women | 477 | 448 | 426 | 468 | 439 | 469 | 520 | 429 | 450 | 454 | 432 | 464 | 493 | 459 | 0.63 |

| Men | 233 | 420 | 478 | 285 | 377 | 321 | 308 | 359 | 461 | 325 | 331 | 357 | 402 | 358 | 8.71 |

AAR average annual rate, AAGR average annual growth rate

**Includes employment, quantitative and qualitative underemployment, underemployment, and household activities

In 2017, in Mexico, there were 292 035 physicians and 591 801 nurses, of which 72.7% and 51.8% were employed 20 h or more in the health sector, respectively. By age, 16.8% of physicians and 27.7% of nurses were younger than 30 years of age, and 15.2% of physicians and 8.3% of nurses were 60 years and older. With regard to education, 25.7% of physicians were specialists or had postgraduate schooling, while 48.3% of nurses were technicians, and only 0.9% had a specialization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of physicians and nurses. Mexico, ENOE Trim III-2017

| Physicians | Nurses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | |

| N | 292 035 | 141 728 | 150 307 | 591 801 | 519 408 | 723 93 |

| n | 1 070 | 444 | 626 | 2 118 | 1 824 | 294 |

| % | 100.0 | 48.5 | 51.5 | 100.0 | 87.8 | 12.2 |

| Employment pattern | ||||||

| Employment | 72.7 [68.4, 76.6] | 68.2 [60.6, 74.9] | 77.0 [72.2, 81.2]* | 51.8 [48.5, 55.0] | 50.7 [47.3, 54.1] | 59.8 [54.6, 64.8]* |

| Quantitative underemployment | 4.6 [3.2, 6.6] | 4.1 [2.6, 6.6] | 5.1 [3.1, 8.3] | 3.6 [2.5, 5.2] | 3.7 [2.5, 5.5] | 2.9 [1.5, 5.4] |

| Qualitative underemployment | 11.5 [9.2, 14.2] | 12.7 [9.3, 17.0] | 10.3 [7.7, 13.6] | 19.4 [16.7, 22.3] | 18.5 [15.6, 21.7] | 25.7 [20.7, 31.4] |

| Underemployment | 1.4 [0.7, 2.8] | 0.5 [0.2, 1.1] | 2.3 [1.1, 4.8] | 3.2 [2.0, 5.1] | 2.3 [1.5, 3.5] | 9.7 [8.2, 11.3] |

| Household activities | 9.8 [7.5, 12.5] | 14.5 [11.0, 18.9] | 5.3 [3.3, 8.2] | 22.0 [19.4, 24.9] | 24.8 [21.9, 28.1] | 2.0 [0.9, 4.3] |

| Age group | ||||||

| 20–29 | 16.8 [13.2, 21.2] | 20.5 [14.2, 28.6] | 13.4 [9.8, 18.1]* | 27.7 [24.8, 30.9] | 25.0 [22.2, 28.1] | 47.2 [42.8, 51.6]* |

| 30–39 | 24.7 [19.6, 30.7] | 27.2 [19.1, 37.1] | 22.4 [17.3, 28.3] | 24.3 [21.4, 27.5] | 24.1 [21.0, 27.6] | 25.5 [19.4, 32.7] |

| 40–49 | 21.8 [14.1, 32.2] | 26.6 [13.0, 46.8] | 17.4 [12.8, 23.2] | 22.8 [19.9, 25.9] | 23.2 [20.1, 26.5] | 20.0 [12.9, 29.6] |

| 50–59 | 21.4 [18.0, 25.2] | 20.5 [15.6, 26.4] | 22.3 [18.3, 26.9] | 16.8 [14.4, 19.5] | 18.2 [15.5, 21.2] | 6.9 [5.4, 8.7] |

| 60–69 | 12.7 [10.2, 15.7] | 4.6 [2.9, 7.1] | 20.3 [16.7, 24.5] | 5.7 [4.0, 8.2] | 6.5 [4.5, 9.3] | 0.4 [0.3, 0.7] |

| 70+ | 2.5 [1.6, 4.0] | 0.7 [0.3, 1.8] | 4.2 [2.5, 6.9] | 2.6 [1.6, 4.3] | 3.0 [1.8, 4.9] | |

| Schooling | ||||||

| Technician | 48.3 [45.1, 51.6] | 49.0 [45.5, 52.5] | 43.9 [38.9, 48.9] | |||

| Graduate | 74.3 [65.0, 81.9] | 74.0 [54.8, 86.9] | 74.7 [69.1, 79.6] | 50.8 [47.5, 54] | 50.2 [46.7, 53.6] | 55.0 [49.9, 60] |

| Specialty/postgraduate | 25.7 [18.1, 35.0] | 26.0 [13.1, 45.2] | 25.3 [20.4, 30.9] | 0.9 [0.5, 1.7] | 0.9 [0.4, 1.7] | 1.2 [0.4, 3.5] |

| Marital status | ||||||

| No partner | 36.3 [30.9, 42] | 44.7 [34.4, 55.5] | 28.3 [23.8, 33.3]* | 43.0 [39.5, 46.6] | 42.9 [39.1, 46.7] | 44.1 [39.3, 48.9] |

| With partner | 63.7 [58, 69.1] | 55.3 [44.5, 65.6] | 71.7 [66.7, 76.2] | 57.0 [53.4, 60.5] | 57.1 [53.3, 60.9] | 55.9 [51.1, 60.7] |

| Location | ||||||

| Rural | 2.7 [2.4, 3.0] | 2.0 [1.7, 2.5] | 3.3 [3.1, 3.4] | 6.5 [5.9, 7.1] | 6.8 [6.2, 7.5] | 3.8 [3.3, 4.3] |

| Urban | 97.3 [97, 97.6] | 98.0 [97.5, 98.3] | 96.7 [96.6, 96.9] | 93.5 [92.9, 94.1] | 93.2 [92.5, 93.8] | 96.2 [95.7, 96.7] |

*P value < 0.05

For both physicians and nurses, women had lower percentages of employment (68.2 and 50.7%, respectively) compared to men (77.0 and 59.8%, respectively). A higher percentage of women were dedicated to household activities (14.5% of female physicians and 24.8% of female nurses compared to 5.3% male physicians and 2.0% of male nurses). Regarding age, 13.4% of male physicians were in the 20–29 age group, whereas 20.5% of female physicians were in that age bracket. For nurses, a lower percentage of female nurses were in the age bracket 20–25 (25.0%) compared to the percentage of men in that bracket (47.2%).

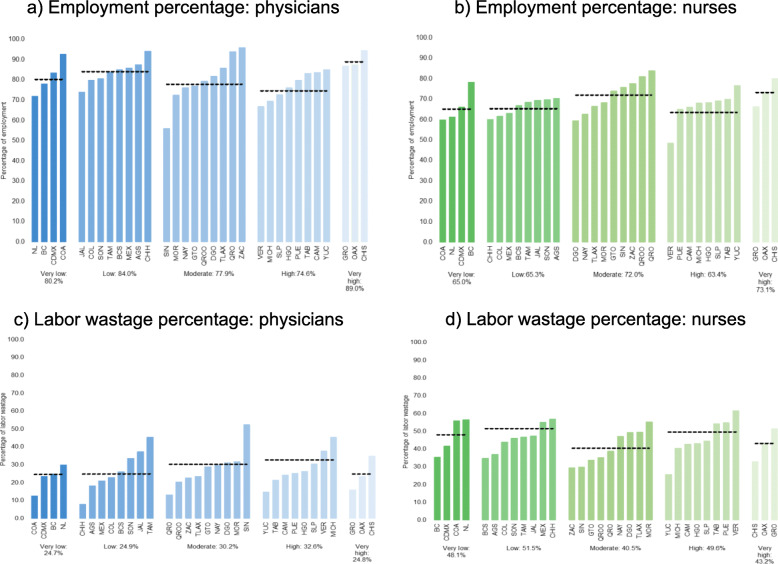

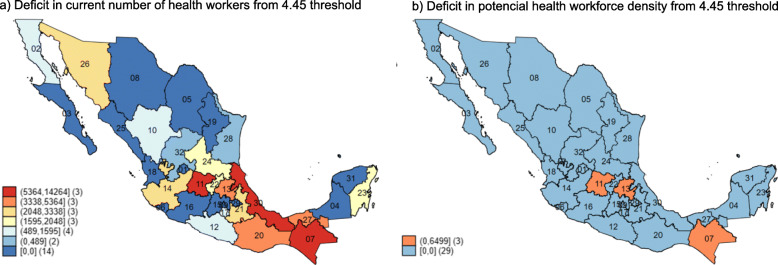

Figure 1 shows the heterogeneity of employment and labor wastage rates for physicians and nurses among the states grouped by level of marginalization. States with the highest marginalization had the highest employment average for both physicians and nurses (Fig. 1a, b). The highest physician labor wastage percentage was found in states with high and moderate marginalization (Fig. 2c). For nurses, the opposite was true, higher labor wastage percentages were found in the states categorized as low and very low categories (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 1.

Rates of employment and labor wastage in physicians and nurses. ENOE TrimIII-2017

Fig. 2.

Deficit in the number of health workers from 4.45 threshold. ENOE TrimIII-2017

In 2017, there were a total of 212 359 physicians (72.7%) and 306 491 nurses (51.8%) employed 20 h or more per week in the health sector in Mexico. Given that there is a population of 123.51 million, and that the EHWD per 1000 inhabitants was 4.2 (1.72 physicians and 2.48 nurses), we estimated a deficit of 70 161 workers to reach the threshold of 4.45 per 1000 as proposed by the GSHRH. At the state level, the estimated gap is heterogeneous. There were 18 states which did not reach the threshold, and the state deficits ranged from 87 workers to 14 264 workers (Fig. 2a). If we consider the potential health workforce density (PHWD), the density per 1000 inhabitants would reach 7.16 (Table 5) and only three states would still remain below the threshold (Fig. 2b). In this scenario, we calculated that a total of 8662 health workers would be required.

Table 5.

Density of health workers by employment pattern. ENOE TrimIII-2017

| Employment pattern | Number of health workers | Cumulative number of health workers | Density | Need | States under the 4.45 threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employed (E) | 518 850 | 518 850 | 4.2 | 70 161 | 18 |

| Quantitative underemployment (QnU) | 34 849 | 553 699 | 4.48 | 57 832 | 15 |

| Qualitative underemployment (QlU) | 148 031 | 701 730 | 5.68 | 23 174 | 8 |

| Unemployment (U) | 23 185 | 724 915 | 5.87 | 21 405 | 7 |

| Household activities (H) | 158 921 | 883 836 | 7.16 | 8 662 | 3 |

In 2017, the total population in Mexico in 2017 was 123 518 269

Discussion

Our study showed that male physicians and female nurses have higher rates of employment compared to their female and male counterparts, respectively. Qualitative underemployment and unemployment are higher in female physicians and male nurses, and labor wastage is higher in both female physicians and female nurses. In this regard, a previous study in Mexico reported that qualitative underemployment among physicians was particularly higher in women in 2006, regardless of the type of academic qualifications, whereas, among nurses, qualitative underemployment was higher among men [22]. Ten years later, although the number of female physicians and male nurses has increased, gender discrepancies still exist, and underemployment and unemployment remain higher among female professionals. Moreover, some studies highlight wage differences in favor of male professionals [24, 25]. In addition, we found that quantitative underemployment is higher in female nurses. Some studies argue that women physicians are more likely to work part-time [26]. Both in medicine and nursing, common reasons for preferring part-time work include time to take care of children under 18 years old [27] or to continue with traditional household activities [28]. It is additionally highlighted that part-time physicians spend more time on teaching and research [26].

Regarding the feminization of physicians, a pattern is observed in most middle-income countries [29, 30] and is likewise becoming evident in Mexico. Between 2005 and 2017, the available workforce of female physicians in Mexico increased by 87% while available male physicians increased by only 3%. By 2017, in Mexico, almost half of the physicians employed in the health sector were women and around 75% of the health workforce (physicians and nurses) were women, with greater participation of women under 50 years than ever before. A similar trend has been observed in China, where about 51% of graduating physicians in 2005 were female, and by 2015, this percentage increased to 56% [31]. In general, the motivating factors for enrolling in medical schools are the scientific rigor of medicine and socioeconomic status and financial perspectives. For females, additional motivators include the social prestige of the profession, better opportunities to marry a professional [32], cultural preference for female physicians in conservative communities, and a desire to help poor people [33]. In response to this feminization of healthcare professions, some studies show positive and negative consequences. Researchers in Africa reported a trend that female physicians perform better standardized examinations [34], spending more time with their patients [35], writing fewer prescriptions, and referring cases more often [36]. However, some developing countries reported that female physicians work fewer hours and perform a lesser workload than their male counterparts [37, 38]. A systematic review showed a small negative impact of feminization on the availability of primary health care services in high-income countries [36].

About nursing in Mexico, we found that 12% of nurses were men in 2017, and the highest percentage of them were in the age category under 30 years old, indicating a recent trend in the growth of male nurses. A similar percentage is observed in the United States of America, where 13.6% of licensed nurses in 2015 were men [39]. The low numbers of males in nursing may be influenced by the social structure, given that this profession has been historically considered to be feminine [40]. Some authors argue that men reduce their social status when choosing the nursing profession, in contrast to women who raise their status [41]. In general, some studies explain gender discrimination in the health workforce due to the persistence of structural, social, and cultural factors that are perceived differently by stakeholders, physicians, and nurses [42].

We found a gap in training at the postgraduate level between physicians and nurses; while 25% of Mexican physicians had a postgraduate degree or specialty, only 1% of nurses had a specialty. This inequity in professional development is partly explained by the fact that the medical profession has specialty programs that are implemented under an academic program and is offered by public institutions with a monthly salary [43, 44]. In fact, we could identify only one relevant institutional initiative offering post-technical courses for nurses led by the Mexican Social Security Institute [17]. In summary, the results demonstrate important differences among physicians and nurses regarding gender and training level when they enter the labor market.

Finally, in terms of indicators of availability of health professionals, if we consider only those physicians and nurses employed in the health sector 20 h or more per week, Mexico has a density of 4.2 per 1000 inhabitants. Only 14 states achieved the threshold suggested in the GSHRH to reach UHC by 2030. If we consider also those who worked in the health sector less than 20 h per week, the density was 4.48 per 1000 inhabitants. The OECD reports a density of 5.33 for the same year but notes that interns and residents are included. In addition, the OECD report uses data from different sources, so double counting may occur as both physicians and nurses can work in the public and private sectors simultaneously [18]. When we consider qualitative underemployment and unemployment, the density was 5.87 and 7.16 per 1000 inhabitants respectively, when we included those dedicated to household activities on a full-time basis. Some studies argued that these negative indicators were due to the concentration of health workers in the areas of greatest development, which offer better opportunities for professional development and better wages [45]. Hence, it is necessary to develop strategies to incorporate into the labor market professionals that are part of labor wastage.

Although the GSHRH does not mention what proportions of physicians and nurses would be adequate, systematic review informs that collaboration between physicians and nurses can have a positive impact on patient outcomes and a variety of pathologies [46]. Further, they conclude that properly trained nurses are capable of as high-quality care as primary care physicians and achieve equally good results in patients [47].

Our study has some limitations. Our estimation of rates of employment does not consider physicians and nurses who participate in teaching and research activities, so quantitative underemployment may be overestimated. Furthermore, it is not possible to distinguish between those who choose to work less than 20 h and those who have to do so because of market conditions. In addition, the analysis at the state level only considers one trimester, and it is not possible to identify labor mobility that can affect rates and state densities over time. Perhaps, in the future, if we choose another quarter or year, such as 2007 or 2014, when employment was at its highest rates, the national density of HRH would reach the threshold of 4.45 per 1000 for those who worked 20 h or more. Subsequent analyses of the time series could help explain possible seasonal cycles in the behavior of rates.

Conclusion

We provide evidence on the existence of gender gaps among physicians and nurses in the labor markets. The rates of employment were higher in men, and rates of unemployment and labor wastage were higher in women. This indicator pointed the disadvantages of the health labor market in Mexico for women, and this phenomenon particularly affects nurses where most of them are female. In general, if the health workers employed 20 h or more per week are considered, the gap to reach the WHO threshold is small; however, this gap decreases as the labor wastage enters the labor market. Therefore, policies on human resources for health should be oriented towards the incorporation of labor wastage in the labor market and the achievement of gender equity in relation to job responsibilities, promotion, retention, and remuneration [48].

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- AAR

Average annual rate

- AAGR

Average annual growth rate

- CONAPO

National Population Council

- ENOE

National Survey of Occupation and Employment

- EHWD

Employed health workforce density

- GSHRH

Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health

- HRH

Human Resources for Health

- HW

Health workforce

- INEGI

National Institute of Statistics and Geography

- LMIC

Low- and middle-income countries

- OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- PHWD

Potential health workforce density

- PHW

Potential health workforce

- SDG

Sustainable Developing Goals

- UHC

Universal health coverage

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

JM: designed the original study, performed the data analysis, drafted the manuscript, and integrated the comments and suggestions of coauthors. JA: Suport in data analysis, drafted the manuscript, integration of comments and suggestions of coauthors. GN: support in data analysis and review all versions of the manuscript. GA: support in data analysis and review the paper. LD: review of all versions and coherence of the final manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the National Institute of Statistics and Geography repository [https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enoe/15ymas/].

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary material files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data available on the INEGI website provide information without identifiers. INEGI’s code of ethics is available at the following link https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/inegi/acercade/doc/codigo_etica.pdf

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mcpake B, Maeda A, Araújo C, Lemiere C, Maghraby E. Why do health labour market forces matter. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:841–846. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.118794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell J, Buchan J, Cometto G, David B, Dussault G, Fogstad H, et al. Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:853–863. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.118729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertone MP, Witter S. The complex remuneration of human resources for health in low-income settings: policy implications and a research agenda for designing effective financial incentives. Human Resources for Health. 2015;13:62. doi: 10.1186/s12960-015-0058-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030. WHO 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/global_strategy_workforce2030_14_print.pdf?ua=1. [cited 2019 Aug 3].

- 5.World Health Organization. Background document towards a global action plan for healthy lives and well-being for all. WHO, 2018. Available from: http://www.who.int/sdg/global-action-plan/GAP_mapping_doc.pdf. [cited 2019 Aug 15].

- 6.Mandeville KL, Lagarde M, Hanson K, Mills A. Human resources for health: time to move out of crisis mode. The Lancet. 2016;388(10041):220–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30952-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anand PS, Bärnighausen T. Human resources and health outcomes: cross-country econometric study. Lancet. 2004;364(9445):1603–1609. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17313-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand S, Bärnighausen T. Health workers and vaccination coverage in developing countries: an econometric analysis. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nkomazana O, Mash R, Shaibu S, Phaladze N. Stakeholders’ perceptions on shortage of healthcare workers in primary healthcare in Botswana: focus group discussions. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheffler RM, Arnold DR. Projecting shortages and surpluses of doctors and nurses in the OECD: what looms ahead. Health Econ Policy Law. 2019;14(2):274–290. doi: 10.1017/S174413311700055X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization. A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health Report. Available from: https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/GHWA-a_universal_truth_report.pdf?ua=1. [cited 2019 Sep 15].

- 12.Shen-Miller D, Smiler AP. Men in female-dominated vocations: a rationale for academic study and introduction to the special issue. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research. 2015;72(7-8):269–276. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Global health workforce shortage to reach 12.9 million in coming decades. Media Centre [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/health-workforce-shortage/en/ [cited 2019 Sep 15].

- 14.Alcalde-Rabanal JE, Nigenda G, Barnighausen T, Velasco-Mondragon HE, Darney BG. The gap in human resources to deliver the guaranteed package of prevention and health promotion services at urban and rural primary care facilities in Mexico. Human Resources for Health. 2017;15:49. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0220-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knaul F, Frenk J, Aguilar AM. The gender composition of the medical profession in Mexico: implications for employment patterns and physician labor supply. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2000;55(1):32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knaul FM, Frenk J, Aguilar M. The gender composition of the medical profession in Mexico: implications for employment patterns and physician labor supply. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2000;55(1):32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esquivel-Rosales R. Cursos Postécnicos en enfermería, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social: una mirada al pasado. Rev Enferm Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2012;20(2):105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD. Stat [Internet] [cited 2020 Feb 24]. Disponible en: https://stats.oecd.org/.

- 19.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo 2018 [Internet]. México, 2018. Available from: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enoe/15ymas/ [cited 2018 Oct 24].

- 20.Dirección General de Información en Salud (DGIS). Cubos dinámicos: Proyecciones CONAPO versión Censo 2010 [Internet]. Secretaría de Salud. 2018. Available from: http://www.dgis.salud.gob.mx/contenidos/basesdedatos/bdc_poblacion_gobmx.html. [cited 2018 Oct 24].

- 21.Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO). Índices de Marginación por Entidad Federativa y Municipio 2010 [Internet]. Secretaría de Gobernación. 2010. Available from: http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Indices_de_Marginacion_2010_por_entidad_federativa_y_municipio. [cited 2018 Oct 24].

- 22.Nigenda G, Ruiz JA, Rosales Y, Bejarano R. Enfermeras con licenciatura en México: Estimación de los niveles de deserción escolar y desperdicio laboral. Salud Publica Mex. 2006;48(1):22–29. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342006000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nigenda G, Ruiz JA, Bejarano R. Educational and labor wastage of doctors in Mexico: towards the construction of a common methodology. Human Resources for Health. 2005;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rad EH, Ehsani-Chimeh E, Gharebehlagh MN, Kokabisaghi F, Rezaei S, Yaghoubi M. Higher income for male physicians: findings about salary differences between male and female Iranian physicians. Balkan Med J. 2019;36(3):162–168. doi: 10.4274/balkanmedj.galenos.2018.2018.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muench U, Dietrich H. The male-female earnings gap for nurses in Germany: a pooled cross-sectional study of the years 2006 and 2012. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;89:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mechaber HF, Levine RB, Manwell LB, et al. Part-time physicians…prevalent, connected, and satisfied. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):300–303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0514-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gravelle H, Hole AR. The work hours of GPs: survey of English GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(535):96–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jamieson L, Williams L, Lauder W, Dwyer T. Nurses’ motivators to work part-time. Collegian. 2007;14(2):13–19. doi: 10.1016/s1322-7696(08)60550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips SP, Austin EB. The feminization of medicine and population health. JAMA. 2009;301(8):863–864. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canesqui AM, Spinelli MADS. Family health in Mato Grosso State, Brazil: profile and assessment by physicians and nurses. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22(9):1881–1892. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006000900019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang C, Tang D. The trend and features of physician workforce supply in China: after national medical licensing system reform. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anukriti S, Dasgupta S. Marriage markets in developing countries. In: Averett S, Argys L, Hoffman S, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy; Aug. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190628963.013.5.

- 33.Kwon E. “For passion or for future family?” Exploring factors influencing career and family choices of female medical students and residents. Gender Issues. 2016;34(2):186–200. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferguson E, James D, Madeley L. Factors associated with success in medical school: systematic review of the literature. BMJ. 2002;324(7343):952–957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7343.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.French F, Andrew J, Awramenko M, Coutts H, Leighton-Beck L, Mollison J, et al. Why do work patterns differ between men and women GPs? J Health Organ Manag. 2006;20(2–3):163–172. doi: 10.1108/14777260610661556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hedden L, Barer ML, Cardiff K, McGrail KM, Law MR, Bourgeault IL. The implications of the feminization of the primary care physician workforce on service supply: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koike S, Matsumoto S, Kodama T, Ide H, Yasunaga H, Imamura T. Estimation of physician supply by specialty and the distribution impact of increasing female physicians in Japan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):180. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crossley TF, Hurley J, Jeon S-H. Physician labour supply in Canada: a cohort analysis. Health Econ. 2009;18(4):437–456. doi: 10.1002/hec.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kovner CT, Djukic M, Jun J, Fletcher J, Fatehi FK, Brewer CS. Diversity and education of the nursing workforce 2006–2016. Nurs Outlook. 2018;66(2):160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meadus RJ. Men in nursing: barriers to recruitment. Nursing Forum. 2000;35(3):5–12. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McMurry TB. The image of male nurses and nursing leadership mobility. Nurs Forum. 2011;46(1):22–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2010.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanley D, Beament T, Falconer D, Haigh M, Saunders R, Stanley K, et al. The male of the species: a profile of men in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(5):1155–1168. doi: 10.1111/jan.12905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Estados Unidos Mexicanos- Secretaría de Salud. Diario Oficial de la Federación. NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-001-SSA3-2012, Educación en salud. Para la organización y funcionamiento de residencias médicas. Available from: http://www.cifrhs.salud.gob.mx/site1/residencias/docs/rm_NOM_001_SSA3_2012.pdf. [cited 2020 Feb 15].

- 44.Fajardo-Dolci G, García-Saiso S, González-Martínez JF. La Formación De Médicos Especialistas en México. Documento de Postura. Fajardo-Dolci G, Santacrus-Varela J, Lavalle-Montalvo C, Editores. Academia Nacional de Medicina/México. 2015;pp31–42. ISBN 978-607-443-514-6.Available from: https://www.anmm.org.mx/publicaciones/CAnivANM150/L30_ANM_Medicos_especialistas.pdf.

- 45.Dussault G, Franceschini C. Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthys E, Remmen R, Van Bogaert P. An overview of systematic reviews on the collaboration between physicians and nurses and the impact on patient outcomes: what can we learn in primary care? BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0698-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD001271. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hannawi S, Al SI. Time to address gender inequalities against female physicians. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33(2):532–541. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the National Institute of Statistics and Geography repository [https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enoe/15ymas/].

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary material files.