Abstract

Suicide is a serious public health issue, particularly for Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islander youth living in rural communities in Hawai‘i. The Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative (HCCI) for Youth Suicide Prevention was implemented to address these concerns and used a strength-based, youthleadership approach to suicide prevention. A qualitative study was completed with youth leaders and adult community coordinators to evaluate the impacts of participating in HCCI. Participants included 9 adult community coordinators and 17 youth leaders ages 13–18 years. Coordinator interviews took place at a location of the interviewee's convenience, and youth leader focus groups were conducted at 1 of 6 rurally-based community organizations. A team of university staff members coded transcripts using a narrative approach and grouped codes into themes. Five themes emerged that fit with an adapted socio-ecological model framework, which included increased knowledge in suicide risk, pride in leadership identity, sense of positive relationships, positive affirmation from community members, and sustainability. Future efforts that focus on youth-related issues are encouraged to integrate a youth leadership model and preventive approach while considering implications such as long-term funding and capitalizing on community strengths and resources.

Keywords: Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, socio-ecological model, suicide prevention, youth

Introduction

Suicide is a serious public health concern. In the United States, suicide is the second leading cause of death for individuals 10–24 years.1–2 Youth suicide prevention strategies have been implemented in various communities and schools to address concerns related to suicide.2–4 Yet studies evaluating the outcomes and impact of suicide prevention programs have generally focused on individual-level changes, such as gatekeepers’ or individual participants’ increased knowledge of suicide prevention and perceived preparedness to help individuals in distress.5–6 Limited research has examined youth-led suicide prevention programs and their potential impacts, and even fewer have evaluated the impacts of suicide prevention programs on multiple levels.7–8

In Hawai‘i, suicide is the second leading cause of death for individuals ages 10–34 years9 and the leading cause of injury-related deaths.10 Youth living in rural communities, and especially Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islanders (NHOPI), are at greater risk of suicide.11 This disparity has been observed in other Indigenous communities and may be attributed to historical trauma and structural inequalities stemming from colonization.12 Despite these disparities, strengths persist in Native Hawaiian communities. For instance, many Native Hawaiian youth report receiving a large amount of emotional and moral support from community members.13

The Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative (HCCI) for Youth Suicide Prevention was created to prevent youth suicide and increase early intervention by engaging youth leaders, community members, and health professionals in Hawai‘i.14–16 Partnerships were developed between the University of Hawai‘i Department of Psychiatry, the Prevent Suicide Hawai‘i Task Force, and 6 rurally-based organizations that serve NHOPI youth.15 HCCI community coordinators were hired in each of the 6 organizations and were responsible for recruiting, training, and facilitating youth leadership groups in their communities. Community coordinators and youth leaders were certified as Connect trainers.7,20 Connect is an evidence-based training program that trains gatekeepers on how to respond to youth who exhibit early warning signs of suicide, decrease stigma surrounding suicide and mental health, increase knowledge of suicide prevention, and increase awareness of community resources.17 In collaboration with HCCI stakeholders, Connect was culturally tailored.7,18 Community coordinators and youth leaders also organized events, activities, and campaigns in their respective communities to promote community awareness of suicide prevention and resources.

HCCI used a youth leadership model that focused on 4 components of prevention: youth empowerment, relationship and team-building activities, suicide prevention training, and community awareness events.16 The youth leaders were also trained in safe messaging guidelines,19 which is an evidence-based suicide prevention strategy that focuses on producing public messages about suicide in a way that is unlikely to increase risk of suicidality for vulnerable individuals.20 The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impacts of the HCCI program based on qualitative data from youth leaders and HCCI community coordinators.

Methods

Participants

Nine adult community coordinators and more than 100 youth leaders participated in HCCI over 4 years. All 9 coordinators were interviewed for this study. Three were male, 6 were female, and the majority were NHOPI. A total of 17 youth leaders (ages 13–18) participated in focus groups that occurred at 4 community organizations. Youth who participated in the focus groups were predominantly male, and the majority were NHOPI.

Measures

Semi-structured guides were developed for coordinator interviews and youth leader focus groups. The questions for the coordinator interviews included, “Were there any benefits you experienced from being an HCCI community coordinator?” Some of the questions for the focus groups included, “What have you learned throughout your experience?” and “How has your family or community responded to your involvement in this youth group?”

Procedures

At the start of HCCI, coordinators completed written consent forms and youth leaders submitted youth assent forms and parental consent forms to participate in ongoing evaluation activities of HCCI. Prior to the interviews and focus groups, coordinators were orally re-consented and youth leaders re-consented by re-signing youth assent forms. Coordinator interviews lasted 60–90 minutes at a location of the coordinator's convenience. Youth leader focus groups took approximately 60 minutes and were conducted at the community organization's site. Interviews and focus groups were conducted by HCCI staff members. This study was approved by the University of Hawai‘i's Institutional Review Board (CHS #19411).

Data Management and Analysis

Interviews and focus groups were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and verified by HCCI staff members. Data were analyzed using NVivo Version 11 (QSR International: Burlington, MA).21–22 The research team used a narrative approach to analyze data. To ensure reliability, HCCI staff members collectively coded 1 of the youth focus groups using consensus coding to create the codebook. HCCI staff members worked in pairs to independently code the remaining interviews and focus groups. If coding pairs disagreed, a third researcher was consulted to achieve consensus among the group.

Results

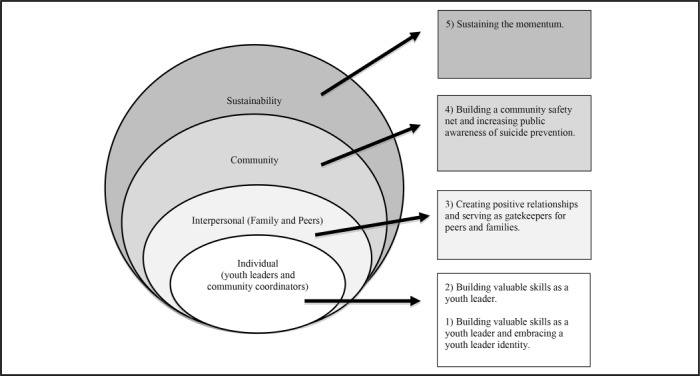

Five program impact themes were identified. The themes aligned with an adapted socio-ecological model (SEM), which was modified into the following levels: (1) the individual level, ie, coordinators and youth leaders; (2) the interpersonal level, ie, peers and families of the youth leaders and community coordinators; and (3) the community level, ie, broader community, recipients of the gatekeeper trainings and community awareness activities (Figure 1). Table 1 provides the major themes and level of impact according to the adapted SEM, codebook definition, and an example of each theme.

Figure 1.

Adapted Socio-Ecological Model of the Impacts of Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative on Youth Leaders and Coordinators

Table 1.

Summary of Themes

| Theme | Codebook Definition | Examples (Quotes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1: Youth leaders building valuable skills and embracing a youth leader identity Individual Level |

Code when interviewee refers to 1 of the following:

|

“My other friend who is also in this group was talking to a boy on Facebook and he admitted that he had thoughts about doing suicide, so she messaged him, and she had the protocols. The first step is always asking, ‘Are you thinking about doing suicide?’ And then he said, ‘Yes.’ so she went on to the next step, which was ‘Do you already have a plan?’ and he said, ‘No.’ So if they say “no,” you just try to talk to them and get them to feel comfortable enough to explain their situation and then if they're comfortable, try to connect them. And so that's what she did.” -Youth Leader, Focus Group |

| 2: Community Coordinators building valuable skills Individual Level |

Code when interviewee refers to 1 of the following:

|

“For me, of course it's being from a generation where it's kind of taboo to talk about it [suicide]. I never really had a sit-down talk about suicide prevention ever or just about the topic of suicide…I didn't know why people would be at risk of suicide until now. So, it benefited me a great deal, knowing all of the risk factors and warning signs, I didn't know that. And then ways of how-to safe message, that's another one I didn't know - and self-care.” -Adult Coordinator, Key Informant Interview |

| 3: Creating positive relationships and serving as gatekeepers for peers and families Interpersonal Level |

Code when interviewee refers to 1 of the following:

|

“I liked that we all had fun but at the same time, we're learning things about suicide and how to help prevent it. Some of the people in our group didn't really talk to each other, and a while after that, we got closer - we bonded.” -Youth Leader, Focus Group |

| 4: Building a community safety net and increasing public awareness of suicide prevention Community Level |

Code when interviewee refers to 1 of the following:

|

“The kids were always open to spread the word, which is good because if it's coming from them, the parents, the adults, the people in the community would listen. It was good to talk about it and bringing the issues up in the community that we can talk about it and that there's help, local help and national help, but overall local help that you can get. And it's not a bad thing to get help. And also, just talking about suicide in general to the whole public. It helped the community a lot I think.” -Adult Coordinator, Key Informant Interview |

| 5: Sustaining the momentum Sustainability |

Code when interviewee refers to 1 of the following:

|

“Overall I have to say the administration [is] extremely supportive. They do try to be community-based as much as possible. They took it a step further than what we were expecting, but it was a positive one. The director made the decision to incorporate it into their curriculum” -Adult Coordinator, Key Informant Interview |

Individual Level: Youth leaders and community coordinators

Theme 1: Youth leaders gained valuable skills and embraced a youth leader identity. According to youth leaders, HCCI helped youth develop valuable skills related to suicide prevention and leadership. The increased knowledge and awareness of suicide prevention was primarily attributed to the youth-focused version of the Connect training. Youth shared stories of how their training helped them become gatekeepers in their schools and communities. Youth leaders assisted in the assessment of crisis situations, conveyed the severity of suicide risk to a trusted adult, and identified community resources with community coordinators and trusted adults. Community coordinators validated the development of valuable skills among youth leaders and referred to youth leaders as the “eyes and ears” of their peers and community.

Youth leaders identified gaining empathy, creativity, and networking skills as a result of their participation in HCCI. Youth leaders also described increased leadership skills and starting to see themselves as leaders. The most common leadership skills included taking on initiatives, fulfilling responsibilities, and learning to manage time. The majority of youth also indicated increased pride in making a difference in their community and growing confidence to take on other leadership roles. The community coordinators also confirmed witnessing this youth development throughout the program.

Theme 2: Community coordinators built valuable skills. Community coordinators also reported gaining valuable career development skills. They discussed how their understanding and comfort with the topic of suicide prevention increased. All coordinators reported increased knowledge of utilizing effec tive strategies to initiate conversations about suicide and raise awareness of suicide prevention. Coordinators also reported enhancing their public speaking skills and community and youth organizing skills by serving as trusted adults for youth leaders while guiding them in coordinating the suicide prevention events. Although the overall focus of HCCI was suicide prevention, coordinators noted the ability to apply the prevention framework in which they were trained to other sensitive health topics, such as child abuse.

Interpersonal Level: Family and Peers

Theme 3: Creating positive relationships and serving as gatekeepers for peers and families. A common theme was the creation of positive relationships among the HCCI youth leaders and community coordinators. HCCI provided opportunities for youth to create positive relationships with each other, community coordinators, other trusted adults, and the larger community. HCCI brought together a diverse group of youth with a shared purpose to address the issue of suicide in their communities. Many of the organizations recruited youth leaders from various social groups who minimally interacted before joining the group. Youth leaders were able to create friendships and bonds while addressing difficult emotions in a shared safe space. Youth leaders also explained that participating in HCCI enhanced their relationships with peers and family members because the leaders were recognized for the positive impacts they were making in their communities. For instance, youth leaders reported that their friends or classmates sought them out if they were in crisis. Similarly, youth leaders and community coordinators reported that family members began to recognize youth leaders and community coordinators as resources in the community with knowledge about suicide prevention. As a result, family members initiated discussions about suicide and mental health with youth leaders and community coordinators.

Community Level

Theme 4: Building a community safety net and increasing public awareness of suicide prevention. Youth leaders and community coordinators shared that their work helped to build a safety net in their community. For example, informal sources of support, such as trusted adults who have frequent contact with the youth, were identified and received training on suicide prevention. Program participation also facilitated partnerships between organizations with similar missions, strengthening the community safety net.17

Coordinators and youth leaders reported witnessing an increased awareness of suicide and suicide prevention in their communities as a result of community awareness events. Community awareness events varied by group and included sign-waving activities, outreach activities, family-friendly events, and t-shirt campaigns. Increased awareness was evidenced by schools and the general community recognizing the youth leader groups and their overall mission. According to participants, people in the community grew receptive to the topic of suicide and were willing to help the youth-led groups. This also helped to address the stigma often associated with suicide and provided a safe opportunity for community members to share personal stories of mental health challenges.

Sustainability

Theme 5: Sustaining the Momentum. Although youth leaders and community coordinators described the overall process and outcomes of HCCI as positive, they expressed the challenge to sustain the momentum. All coordinators agreed that the 1-year funding support they received was too short for the youth leader groups to meet their goals and/or sustain their efforts of suicide prevention. The community coordinators spoke about the importance of having organizational support to facilitate the success of the program, while community coordinators and youth leaders collectively discussed the importance of engaging more leaders and adults to increase buy-in from the community. Youth leaders enthusiastically expressed their interest to continue the program and see it grow to reach the wider community. This sentiment was expressed by most coordinators who felt HCCI motivated youth to continue their efforts irrespective of organizational support.

Discussion

This study identified multi-level impacts, including benefits and challenges of HCCI. Findings highlight the importance of involving youth as leaders in suicide prevention efforts rather than solely as recipients. Through HCCI, youth leaders increased skills related to suicide prevention and leadership. HCCI also provided a space for relationship-building between peers and trusted adults who provided guidance and support. For youth, having positive adult figures is a major protective factor during development.23 Providing youth with structured opportunities, connections to people, and environments also aid in the positive development.24–25 These findings align with other strength-based approaches that have been incorporated in suicide prevention efforts, such as the Sources of Strength program, a suicide prevention program that aims to build socioecological protective factors and decrease suicide risk factors.26

Youth leaders and community coordinators reported being identified as gatekeepers by their peers, family members, and the general community due to their ability to provide access to resources. The development of protocols and participation in suicide prevention trainings helped to establish processes for supporting people in crisis. The youth-led activities helped to initiate conversations about suicide in the community while reducing stigma that is often associated with this topic, which reflect the findings from similar studies.27–28 Community organizations with similar missions were also able to collaborate, increasing the visibility of community strengths and helping to facilitate a safety net in community. Recognition of community strengths and resources is important, especially when integrating best practices of suicide prevention, such as safe messaging, into the community.

Despite the benefits of the program and participants responding favorably to HCCI, sustainability was challenging. Lengthening the time period for funding mechanisms would have been beneficial to ensure sufficient support was in place for staff to dedicate their time and efforts. It is recommended that future program planners provide ample time for relationship-building, provide ongoing and responsive team-building opportunities throughout the program, and pay close attention to the needs and dynamics of the group.16 Although efforts were made to find alternative funding to ensure long-term suicide prevention efforts in the community, few resources were secured. Rather than community specific programming, a state-wide initiative was established to maintain the safety net created during the HCCI program. Long-term (multi-year) funding continues to be sought in order to provide support to individuals and organizations who would like to continue raising awareness in the community and thus address the stigma around sensitive topics related to mental health concerns.

The findings of this study may be limited by the role of HCCI staff in the data collection, which could have led to social desirability bias. Participants may have felt pressured to provide only positive feedback. Nonetheless, suggestions for sustainability and success of future programs were readily provided, and areas of improvement were identified. This openness may have been due to the existing relationships and the trust that HCCI staff had with community partners. Furthermore, findings may reflect the perceptions of a limited sample of youth leaders. Obtaining multiple perspectives from the other youth leaders who participated in the HCCI program as well as other stakeholders in the community, such as peers, family members, school staff, and community members would help to validate these findings.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the youth leaders, community partners, and university staff of the Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative for their ongoing support and dedication to suicide prevention and mental wellness.

Abbreviations

- HCCI

Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative for Youth Suicide Prevention

- NHOPI

Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander

- SAMHSA

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- SEM

socio-ecological model

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclosure Statement

This work was supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) under grant number 1U79SM060394. The views, opinions and content of this publication are those of the authors and contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of SAMHSA.

References

- 1.Heron M. National vital statistics reports. Deaths: Leading causes for 2015. https://www.cdc. gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr66/nvsr66_05.pdf. November 27, 2017. Accessed November 16, 2019. [PubMed]

- 2.King KA, Smith J. Project SOAR: A training program to increase school counselors’ knowledge and confidence regarding suicide prevention and intervention. J School Health. 2000;70:402–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lafromboise TD, Lewis HA. The Zuni Life Skills Development Program: A school/community-based suicide prevention intervention. Suicide Life-Threat. 2008;38:343–353. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasco S, Wallack C, Sartin RM, Dayton R. The impact of experiential exercises on communication and relational skills in a suicide prevention gatekeeper-training program for college resident advisors. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60:134–140. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.623489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bean G, Baber KM. Connect: An effective community-based youth suicide prevention program. Suicide Life-threat. 2011;41:87. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capp K, Deane FP, Lambert G. Suicide prevention in Aboriginal communities: Application of community gatekeeper training. AustNZJPubl Heal. 2001;25:315–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer RJ, Kapusta ND. A social-ecological framework of theory, assessment, and prevention of suicide. Front psychol. 2017;8:1756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry CS. Adolescent Suicide and Families: An Ecological Approach. Adolescence. 1993;28:291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Foundation for Suicide Prevention State fact sheets. Suicide facts and figures: Hawai‘i 2019. https://afsp.org/about-suicide/state-fact-sheets/#Hawaii. Updated 2020. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 10.Galanis D. Honolulu, HI: 2014. Jan 23, Hawaii Department of Health, Injury Prevention Program. PowerPoint Presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Prevent Suicide Hawai‘i Taskforce Report to the Hawai‘i State Legislature Twenty-ninth Legislature, 2018. 2017. Dec 28, State of Hawai‘i. https://health.hawaii.gov/opppd/files/2018/01/HCR66-stratplan_report_180109_final2_with-appendix.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2020.

- 12.Brave Heart MYH, Chase J, Elkins J, Altschul DB. Historical trauma among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research, and clinical considerations. JPsychoactive Drugs. 2011;43:282–290. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medeiros S. Ho‘omau i Nā ‘Ōpio : findings from the 2008 pilot test of the Nā ‘Ōpio: Youth development and assets survey. In: Tibbetts K, Kamehameha Schools R, Evaluation D, editors. Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools, Research & Evaluation Division; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung-Do JJ, Napoli SB, Hooper K, Tydingco T, Bifulco K, Goebert D. Youth-led suicide prevention in an Indigenous rural community. Psychiatr Times. 2014. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/cultural-psychiatry/youth-led-suicide-prevention-indigenous-rural-community.

- 15.Chung-Do JJ, Goebert DA, Bifulco K, Tydingco T, Alvarez A, Rehuher D., Wilcox P. Hawai‘i's Caring Communities Initiative: Mobilizing rural and ethnic minority communities for youth suicide prevention. JHealth Disparities Res Pract. 2015;8:108–123. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugimoto-Matsuda J, Rehuher D. Suicide prevention in diverse populations: a systems and readiness approach for emergency settings. (Cultural Psychiatry) Psychiatr Times. 2014;31:40G. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wyman PA, Brown CH, Inman J, et al. Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. J Consult Clin Psych. 2008;76:104–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung-Do JJ, Bifulco K, Antonio M, Tydingco T, Helm S, Goebert DA. A cultural analysis of the NAMI-NH connect suicide prevention program by rural community leaders in Hawai‘i. JRural Mental Health. 2016;40:87–102. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gould M, Jamieson P, Romer D. Media contagion and suicide among the young. Am Behav Sci. 2003;46:1269–1284. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung-Do JJ, Goebert DA, Bifulco K, et al. Insights in Public Health: Safe messaging for youth-led suicide prevention awareness: Examples from Hawai’i. Hawai’i J Med Public Health. 2016;75:144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Beyond constant comparison qualitative data analysis: Using NVivo. School Psychology Quarterly. 2011;26:70–84. [Google Scholar]

- 22.NVivo qualitative data analysis Software. QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 11, 2016.

- 23.Werner EE. Resilient children. Young children. 1984;40:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damon W. What is positive youth development? ANN Am Acad Polit SS. 2004;591:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Von Eye A, Bowers EP, Lewin-Bizan S. Individual and contextual bases of thriving in adolescence: A view of the issues. J Adolescence. 2011;34:1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyman PA, Brown CH, Lomurray M, et al. An outcome evaluation of the Sources of Strength suicide prevention program delivered by adolescent peer leaders in high schools. Am J Public Health. 2010;100((9)):1653. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millstein R, Sallis J. Youth advocacy for obesity prevention: the next wave of social change for health. Pr Pol Res. 2011;1((3)):497–505. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0060-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winkleby MA, Feighery EC, Altman DA, Kole S, Tencati E. Engaging ethnically diverse teens in a substance use prevention advocacy program. Am J Health Promot. 2001;15((6)):433–436. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.6.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]