Dear Editor,

In late February 2020 the Lombardy region (Italy) was dramatically hit by a new infectious coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (Sars-CoV-2). COVID-19 is paucisymptomatic in the majority of patients but can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in up to 30% of cases and to death in 3 to 5% of cases [1]. Accumulating evidence suggests that severe COVID-19 manifestations are sustained by a “cytokine storm” triggered by Sars-CoV-2 mediated inflammasome activation [2,3]. Of note, this hyper-inflammatory state is typically preceded by 5 to 10 days of spiking fever that takes over mild influenza-like symptoms, suggesting that, after a first phase characterized by viral spread, COVID-19 might progress to an uncontrolled cytokine release syndrome [[1], [2], [3]].

COVID-19 was aggressively faced by the Italian healthcare authorities with restrictive containment measures but, despite that, Lombardy still records 11.337 deaths, 12.043 hospitalized individuals, and 1.073 critically ill patients at the time of writing [www.salute.gov.it]. Because these numbers exceed the maximum capacity of available intensive care units (ICU), patients are asked to stay at home until advanced respiratory impairment, thus increasing the lethality of COVID-19 [4]. In shortage of ICU beds, treating patients at risk of developing hyper-inflammatory ARDS in outpatient settings becomes, therefore, imperative in order to impact disease course and to relieve the pressure on hospitals' structures. Yet, in the absence of effective antiviral therapies and reliable predictors of negative disease progression, this neglected category of patients can rely only on supportive measures while awaiting for clinical deterioration and transportation to emergency departments.

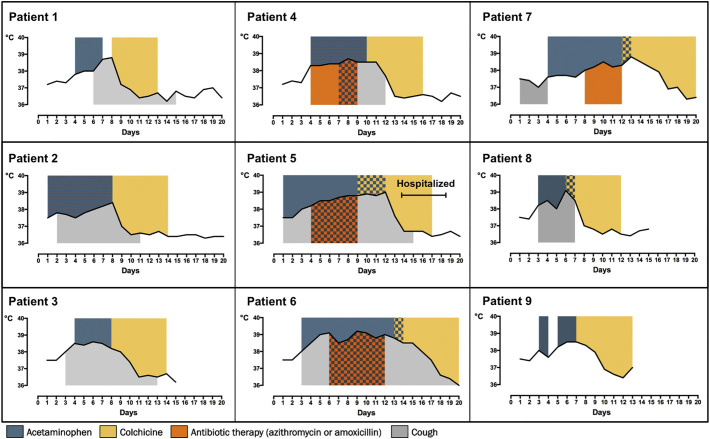

We herein report the favourable outcome of 9 domiciliary consecutive COVID-19 patients treated with a loading dose of 1 mg oral colchicine 12 h apart followed by 1 mg daily colchicine until third day of axillary temperature < 37.5 °C. Colchicine was started after a median of 8 days (range 6–13) from COVID-19 onset and after 3 to 5 days of spiking fever despite acetaminophen or antibiotic treatment. As shown in Fig. 1 , colchicine led to defervescence within 72 h in all patients. Only one patient was hospitalized because of persisting dyspnea and discharged after four days of low-flow oxygen therapy. Colchicine was in general well tolerated. Two patients reported a mild diarrhea that did not interfere with the completion of the treatment.

Fig. 1.

Time-course of fever progression in patients treated with colchicine.

Colchicine is an alkaloid extracted from the autumn colchicum, an herbaceous plant belonging to the Liliaceae family. Its analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties has been known since ancient times, and colchicine is now approved to treat autoinflammatory conditions such as gout, familiar Mediterranean fever, and pericarditis [5]. In the present study, colchicine was used off-label based on its capability to interfere with pathogenic mechanisms implicated in COVID-19 related hyper-inflammation, including inflammasome activation and cytokines release [2,3,5]. In addition, by interfering with the polymerization of microtubules, colchicine inhibits the chemotaxis of monocytes and neutrophils, cells that have been abundantly found in the lungs of COVID-19 patients [[1], [2], [3],6]. Our hypothesis-driven experience supports the use of colchicine in outpatient settings to intercept rampant “cytokine storm” in a subset of patients with hyper-inflammatory phenotype clinically characterized by persistent high fever.

Notably, this population of patients is considered at high risk of progression to respiratory failure, and typically shows increased serum levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 [[1], [2], [3]]. Based on this evidence, patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 are currently being treated with anti-cytokine biologic drugs including the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra and the IL-6 receptor blockers tocilizumab and sarilumab [[7], [8], [9]]. Yet, although these targeted approaches have provided encouraging results in preliminary retrospective cohorts, they do not seem to induce a prompt recovery as optimistically expected, likely because administered at a later stage of the disease when irreversible organ damage is already established [[7], [8], [9]]. Treating COVID-19 patients early in the rampant phase of systemic inflammation becomes, therefore, essential in order to prevent tissue damage caused by an uncontrolled “cytokine storm”. In this regard, identifying the right therapeutic window where anti-inflammatory treatment might perform better is not a trivial concern since early colchicine administration could impair physiological immune response to Sars-CoV-2 while late administration might not be as effective on established ARDS.

Keeping into consideration the limitations of an uncontrolled case series, our study cohort represents the first describing the use of colchicine in COVID-19 on the territory. In a setting overwhelmed by COVID-19 and in shortage of ICU resources - as Lombardy was when hit by the pandemic - colchicine may allow relieving pressure on emergency departments and reducing hospitalizations. Large randomized controlled trials in both inpatient and outpatient settings will definitively confirm the utility of colchicine in the current and future COVID-19 outbreaks.

References

- 1.Wang Dawei, Hu Bo, Hu Chang. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020:e201585. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuki K., Fujiogi M., Koutsogiannaki S. COVID-19 pathophysiology: a review. Clin. Immunol. 2020;215 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felsenstein S., Herbert J.A., McNamara P.S., Hedrich C.M. COVID-19: immunology and treatment options. Clin. Immunol. 2020;215 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remuzzi G., Remuzzi A. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mancuso G., Boffini N., Dagna L. Colchicine as a new therapeutic option for antithyroid arthritis syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019:kez547. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P., Haberecker M., Andermatt R., Zinkernagel A.S., Mehra M.R. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavalli G., De Luca G., Campochiaro C., Della-Torre E., Ripa M., Canetti D. Interleukin-1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheum. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30127-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campochiaro C., Della-Torre E., Cavalli G., De Luca G., Ripa M., Boffini N. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in severe COVID-19 patients: a single-Centre retrospective cohort study. Eur J Int Med. May 22, 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.021. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Della-Torre E., Campochiaro C., Cavalli G., De Luca G., Napolitano A., La Marca S. 2020. Interleukin-6 Blockade with Sarilumab in Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia with Systemic Hyper-Inflammation. (Under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]