Highlights

-

•

COVID-19 is a common pathology that may affect diverse organs, including the central and peripheral nervous system.

-

•

Coronaviruses have important neurotropic potential and they cause neurological alterations that range from mild to severe.

-

•

CoV may affect any age group; the main symptoms are headache, dizziness, and altered consciousness.

-

•

The neurological symptoms caused by CoV (MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV2) are similar.

Abbreviations: ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; ADEM, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis; ANHE, acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy; BBE, Bickerstaff’s encephalitis; βCoV, betacoronavírus; CoV, coronavirus; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; DPP4, dipeptidil peptidase 4; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF); GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HCoV, Human coronavirus; HCoV-229E, Human coronavirus 229E; HCoV-OC43, Human coronavirus OC43; ICU, intensive care unit; IL, interleukin; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS‐CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Keywords: Coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Neurologic manifestations, Encephalopathy

Abstract

Objective

To describe the main neurological manifestations related to coronavirus infection in humans.

Methodology

A systematic review was conducted regarding clinical studies on cases that had neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. The search was carried out in the electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and LILACS with the following keywords: “coronavirus” or “Sars-CoV-2” or “COVID-19” and “neurologic manifestations” or “neurological symptoms” or “meningitis” or “encephalitis” or “encephalopathy,” following the Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Results

Seven studies were included. Neurological alterations after CoV infection may vary from 17.3% to 36.4% and, in the pediatric age range, encephalitis may be as frequent as respiratory disorders, affecting 11 % and 12 % of patients, respectively. The Investigation included 409 patients diagnosed with CoV infection who presented neurological symptoms, with median age range varying from 3 to 62 years. The main neurological alterations were headache (69; 16.8 %), dizziness (57, 13.9 %), altered consciousness (46; 11.2 %), vomiting (26; 6.3 %), epileptic crises (7; 1.7 %), neuralgia (5; 1.2 %), and ataxia (3; 0.7 %). The main presumed diagnoses were acute viral meningitis/encephalitis in 25 (6.1 %) patients, hypoxic encephalopathy in 23 (5.6 %) patients, acute cerebrovascular disease in 6 (1.4 %) patients, 1 (0.2 %) patient with possible acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, 1 (0.2 %) patient with acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy, and 2 (1.4 %) patients with CoV related to Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Conclusion

Coronaviruses have important neurotropic potential and they cause neurological alterations that range from mild to severe. The main neurological manifestations found were headache, dizziness and altered consciousness.

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoV) introduction are pleomorphic RNA viruses whose crown-shaped peplomers are from 80 to 160 nM in size, with 27–32 kb positive polarity (Sahin, 2020). They belong to the family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales, and they spread pathologically in the respiratory, intestinal, liver, and nervous systems (Yin, 2020). They are also zoonotic pathogens considered highly deleterious to human beings given their association with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Sahin, 2020). In addition to respiratory repercussions, accumulated clinical evidence strongly suggests that opportunistic pathogens are capable of overcoming immune responses and affecting extrarespiratory organs, including the central nervous system (CNS).

In addition to their structural characteristics and biological classifications, the recombination rates of CoVs are very high due to the constant development of transcription errors and RNA dependent RNA polymerase jumps (Sahin, 2020). Genomic analysis has indicated that SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 share a highly homological sequence, which also justifies assigning both to the betacoronavirus (βCoV) clade. In agreement with this, public evidence has shown that COVID‐19 also shares similar pathogenesis with pneumonia induced by SARS‐CoV or Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV. The neuroinvasive mechanisms of CoVs have been documented in almost all βCoVs, including SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, human coronavirus (HCoV)-229E, and HCoV-OC43 (Li, Bai, & Hashikawa, 2020; Wu et al., 2020).

Given the possible important repercussions on the CNS and the urgent need to understand COVID-19 clearly, the objective of this study is to discuss, by means of a systematic review, the interface between SARS-CoV-2 and the human nervous system, analyzing its neurotropism and neurological manifestations in patients diagnosed with CoV.

2. Methods

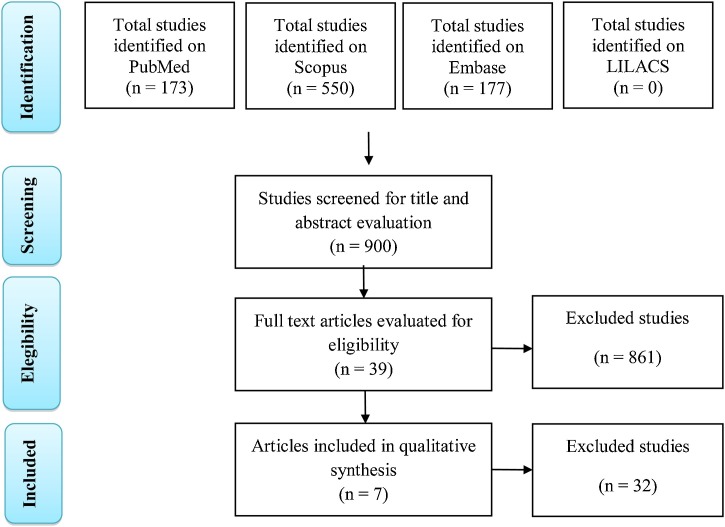

A systematic review was conducted in the electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and LILACS, selecting articles published until April 10, 2020, with the following keywords: “coronavirus” or “Sars-CoV-2” or “COVID-19” and “neurologic manifestations” or “neurological symptoms” or “meningitis” or “encephalitis” or “encephalopathy,” following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Original articles that studied neurological manifestations of patients with CoV infection were selected. There were no restrictions on language or search time. No limit was used for the initial date to identify articles published in the literature until April 10, 2020.Two researchers examined the databanks, and evaluation was solicited from a third researcher in the event of discrepancies or doubts regarding the sources’ relevance.

Only clinical studies containing neurological manifestations associated with COVID-19 and other human CoVs were included. Due to the scarcity of studies on COVID-19, case reports were included only for SARS-CoV-2 infection. The following exclusion criteria were applied: case reports of other CoVs, animal studies, reviews of the literature, and studies that did not cover neurological repercussions of CoV in humans. Data related to the neurological clinical manifestations associated with CoV infection were extracted. The primary outcome was analysis neurological repercussions and their prevalence in the clinical evolution of human patients affected by CoV.

3. Results

Initially, 900 studies were indentifies in the databases searched (173 in PubMed, 550 in Scorpus, 177 in Embase, and 0 in LILACS). Following exclusion based on title and abstract, 39 articles were selected for full-text analysis. Finally, seven articles were selected as relevant to the present study (Fig. 1 ), namely, two studies on the neurological behavior of MERS-CoV, a study on the cytokine profile of patients with CoV infections in the CNS, a study on the characteristics of patients who died after CoV infection, a study on the neurological manifestations of patients hospitalized for COVID-19, and two case reports of COVID-19 with neurological alterations. The main characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Table 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flowchart summarizing the search strategy for studies. Adapted from Moher et al. (2009).

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the selected studies.

| Author and Year | Study Location | Objective | Methodology | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabi et al. (2015) | Saudi Arabia | To observe the association between three cases with neurological symptoms in patients with MERS-CoV. | Retrospective data collection in three cases admitted to the ICU in King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh with MERS-CoV. | The patients presented severe neurological syndrome, characterized by altered consciousness, ataxia, and focal motor deficit. Brain MRI revealed striking changes. | Involvement of the CNS should be considered in patients with MERS-CoV and progressive neurological disease; it is necessary to elucidate the pathophysiology further. |

| Li et al. (2017) | China | To explore cytokine expression profiles of children hospitalized with CoV-CNS and CoV-respiratory infections. | The authors collected and analyzed clinical and laboratory data of 183 children hospitalized with clinical suspicion of acute encephalitis and 236 children with acute respiratory tract infection in Hunan, China. | A fraction of the sample with acute encephalitis was identified with CoV infection. Patients with CoV-CNS infection presented a different cytokine profile than those with CoV-respiratory infection. | CoV-CNS infection may be common and express multiple cytokines with possible immune impairment of the nervous system. |

| Kim et al. (2017) | South Korea | To evaluate neurological manifestations in patients with MERS-CoV. | Retrospective analysis of clinical, laboratory, and imaging records of 23 patients with MERS-CoV in South Korea. | Four patients were found to have neurological complications during treatment for MERS. The most probably diagnoses were GBS, BBE, ICU-acquired weakness, or other toxic or infectious neuropathy. | Neurological complications exist in MERS-CoV. They are not rare, and they interfere with prognosis and may require adequate treatment. |

| Mao et al. (2020) | China | To study neurological manifestations of patients hospitalized with COVID-19. | Retrospective study through review of clinical records and laboratory and imaging exams of 214 patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. | A number of patients had neurological manifestations in the central or peripheral nervous system or proven skeletal muscular injuries. | SARS-CoV-2 may infect the nervous system and lead to neurological manifestations, especially in severe cases. |

| Chen et al. (2020) | China | To describe the clinical characteristics of patients who died of COVID-19. | Retrospective case series through study of clinical, laboratory, and imaging data of 113 patients who died of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. | Hypoxic encephalopathy was a common complication in patients who died, showing a potential association with clinical outcome. | The development of neurological complications is strongly associated with negative results in patients with COVID-19. |

| Moriguchi et al. (2020) | Japan | To report a case of neurological involvement associated with SARS-CoV-2. | Clinical analysis of the case, report of symptoms, and specimen collection testing for SARS-CoV-2 were conducted. | Magnetic resonance showed abnormal findings in the medial temporal lobe, including the hippocampus, suggesting encephalitis, hippocampal sclerosis, or post-convulsive encephalitis. | The study indicated the neuroinvasive potential of the virus, as well as its presence even when nasopharyngeal sample tests negative. |

| Poyiadji et al. (2020), | United States of America | To report the first presumed case of acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy associated with COVID-19. | Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 was made by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR assay. The authors analyzed CSF, as well as CT and MRI. | Noncontrast head CT demonstrated symmetric hypoattenuation in thalamic regions. Brain MRI demonstrated lesions that enhanced the hemorrhagic rim. | To the extent that the number of cases of COVID-19 increases around the world, clinical physicians and radiologists should be aware of this presentation among patients who present COVID-19 and altered mental status. |

Legends: BBE: Bickerstaff’s encephalitis, GBS: Guillain-Barré syndrome, ICU: Intensive Care Unit.

The present study included 409 patients diagnosed with CoV infection who presented neurological symptoms. The median age range of patients in the studies ranged from 3 to 62 years of age. The following neurological alterations were described: headache (69; 16.8 %), dizziness (57, 13.9 %), altered consciousness (46; 11.2 %), vomiting (26; 6.3 %), epileptic crises (7; 1.7 %), neuralgia (5; 1.2 %), and ataxia (3; 0.7 %). The most common presumed diagnoses were acute viral meningitis/encephalitis in 25 (6.1 %) patients, hypoxic encephalopathy in 23 (5.6 %) patients, acute cerebrovascular disease in 6 (1.4 %) patients, 1 (0.2 %) patient with possible ADEM, 1 (0.2 %) patient with acute necrotizing hemorrhagic encephalopathy (ANHE), and 2 (1.4 %) patients with CoV related to GBS.

In Wuhan, of the 214 patients with COVID-19 evaluated, 78 (36.4 %) presented neurological alterations. In relation to MERS, of the 23 patients evaluated in South Korea, four (17.3 %) evolved with neurological symptoms. In a study of 183 patients in the pediatric age range (under 16 years of age) with encephalitis, 22 (12 %) had CoV infection. These data are very similar to those in patients with respiratory syndrome (236 patients), 26 of which (11 %) had confirmed diagnosis of CoV-respiratory tract infection. Evaluating mortality in patients infected by CoV, 25 patients (22.1 %) who died showed altered consciousness in a study of 799 patients with 113 deaths (14.1 %).

4. Discussion

A priori, several studies have described the association of CoVs with CNS diseases, such as ADEM and multiple sclerosis. Furthermore, it is known that the mortality of viral encephalitis is approximately 29 %, and almost 50 % of those who survive have a high risk of developing neurological disorders. The effect of CoV infection is influenced by diverse factors, including environmental interference, genetics, and immune-mediate processes. Cytokines are widely known as important inflammatory response mediators (Bell, Taub, & Perry, 1996). This panorama includes interleukin (IL)-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine that induces terminal differentiation of B cells in plasma cells, stimulates secretion of antibodies, and improves T lymphocyte responses in secondary lymphoid organs. Furthermore, IL-8 is a chemokine that functions as a potent chemotactic agent for polymorphonuclear cells and lymphocytes, associated with the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. These are in addition to MCP-1, a chemokine that may initiate transmigration of monocytes across the blood-brain barrier (Kaplanski et al., 1995).

Accordingly, IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 contribute to severe progression of respiratory diseases in SARS infections. The expression of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is frequently induced during CoV infections, resulting in systemic infection, where it is possible to identify an increase in inflammatory fluids, as in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and severe respiratory syncytial virus infection (Dodd, Giddings, & Kirkegaard, 2001). Other studies have suggested that granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) also has pro-inflammatory functions and that it plays critical roles in the development of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, such as autoimmune encephalomyelitis (Zhang et al., 2004).

Accordingly, analyses by Yuanyuan Li et al. (2017) showed a relation in increased serum levels of these inflammatory precursors described in patients whose CNS was affected. The authors observed a significant increase in serum G-CSF in patients with CoV-CNS or CoV-respiratory infections. G-CSF is one of the main regulators of granulocytosis, which plays a central role in stimulating the proliferation of granulocytic precursors, improves their terminal differentiation, and stimulates their release from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood. Furthermore, GM-CSF stimulates stem cells to produce granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils) and monocytes. These results showed (1) that infection induces a high level of GM-CSF in CSF serum and (2) that peripheral cell, monocyte, and neutrophil counts were significantly higher in patients with CoV-CNS infection than in patients with CoV-respiratory infection and healthy controls. These findings may suggest that GM-CSF plays an important role in controlling CNS infection through the induction of neutrophils and the proliferation and/or accumulation of monocytes in the infection site.

Li et al. (2017) emphasize that IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 were significantly accumulated in the CSF of patients with CoV-CNS infection. IL-6 has neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects, and it may increase the blood concentration and permeability of the barrier. High levels of IL-6 lead to progressive neurological disorders with neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. The higher levels of IL-8 in the CSF observed in this study are consistent with the fact that viral infection of the CNS may induce proliferation of microglia and astrocytes, resulting in the release of IL-8. MCP-1 is also a chemokine that may initiate monocyte transmigration across the blood-brain barrier and recruit inflammatory cells to the CNS, thus facilitating the entrance of cells infected by the virus, also amplifying the inflammatory response, which damages the brain. These accumulated cytokines can also contribute to immune damage in the CNS in patients with CoV infection similar to that observed in other viral encephalitis. In conclusion, the study suggests that CoV-CNS infection is common and many cytokine profiles are involved in the host’s initial immune response to infection, which may induce immune compromise in the brain. This study, thus, underlines the importance of CoV’s neurotrophic capacity and its involvement in the CNS.

The studies by Ling Mao et al. (2020) in Wuhan, the initial epicenter of the COVID-19 infection, report that patients with COVID-19 may present neurological manifestations. In an analysis of 214 patients with COVID-19, 126 patients (58.9 %) had non-severe infection, and 88 (41.1 %) had severe infection, according to their respiratory status. Compared with patients with non-severe infections, patients with severe disease were older, and they presented more underlying disorders, especially hypertension, and fewer typical symptoms of COVID-19, such as fever and cough. Overall, 78 patients (36.4 %) presented neurological manifestations, more in the CNS (24.8 %) that in the peripheral nervous system (8.9 %), and muscle injury (10.7 %). Regarding alterations in the CNS, the following were observed, in descending order of prevalence: dizziness, headache, impaired consciousness, cerebrovascular events (ischemic or hemorrhagic), ataxia, and epilepsy. In the peripheral nervous system, hypogeusia, hyposmia, and neuralgia were described. The authors, thus, emphasize that, during the epidemic period of COVID-19, when attending patients with neurological manifestations, doctors should suspect SARS-CoV-2 infection as a differential diagnosis in order to avoid diagnostic delays, misdiagnoses, and loss of opportunity to treat and prevent further transmission.

In following with this principle, Tao Chen et al. (2020) described the clinical characteristics of 113 patients who died of COVID-19. Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine, creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, cardiac troponin I, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, and D-dimer concentrations were distinctively higher in patients who died than in those who those who recovered. The complications most commonly observed in patients who died included acute respiratory distress syndrome (113; 100 %), type I respiratory failure (18/35; 51 %), sepsis (113; 100 %), acute cardiac lesion (72/94; 77 %), heart failure (41/83; 49 %), alkalosis (14/35; 40 %), hyperkalemia (42; 37 %), acute renal injury (28; 25 %), and hypoxic encephalopathy (23; 20 %). Hypoxic encephalopathy has been described in other analyses as associated with the group of viruses under discussion. This relation may be the result of respiratory tract involvement itself due to latent infection in conjunction with the direct action of the inflammatory process in the CNS.

MERS is also caused by infection with the CoV MERS-CoV, which belongs to the same genus βCoV, with similar structure, signs, and symptoms to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV2. However, the important difference shown is that MERS-CoV uses dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4 or CD26) as a receptor, differently from SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV2 that use ACE2. DPP4 is expressed in T cells, also present in the lungs, kidney, placenta, liver, skeletal muscles, heart, pancreas, endothelium, and brain (Arabi et al., 2015; Cui, Li, & Shi, 2019; Kim et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020; Yuan et al., 2017).

The first report of MERS-CoV occurred in 2012, in Saudi Arabia, with 1826 cases confirmed in 27 countries, with 35.5 % mortality(Arabi et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017). Patients may present as asymptomatic or have symptoms such as fever, myalgia, cough, and dyspnea, and they may evolve with pneumonia and, in more severe cases, acute respiratory syndrome, sepsis, multiple organ failure, and death. Registered neurological alterations include epileptic crises, ADEM, encephalopathy, and polyneuropathy(Arabi et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017).

Arabi et al. (2015) reported the first cases of neurological alterations caused by MERS-CoV in the literature, with three patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit (ICU) in King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The three patients, ages 74, 57, and 45 years, had previous comorbidities, and they spent part of their hospitalization in the ICU. The first case presented ataxia, vomiting, mental confusion, with chest radiography showing evidence of pulmonary infiltrate. Brain CT and MRI indicated multiply chronic lacunar strokes, without any acute alterations. The patient subsequently evolved with respiratory worsening (severe acute respiratory distress syndrome), requiring mechanical ventilation. The patient received oseltamivir, bronchodilators, methylprednisolone, peginterferon alpha-2b, and ribavirin. There was subsequent improvement in respiratory status, with neurological worsening, however. A new brain CT was performed, showing evidence of new irregular hypodensities in the periventricular deep white matter, bilateral basal ganglia, thalami, pons, cerebellum, and cerebellar pedicles, as well as a large hypodensity in the splenium and the corpus callosum. MRI revealed multiple areas of signal abnormality in the periventricular deep white matter, subcortical area, corpus callosum, pons, mesencephalon, cerebellum, and upper cervical cord.

The other two cases reported by Arabi et al. (2015) initially presented mild respiratory symptoms and fever before the neurological symptoms. Both also required mechanical ventilation. One was diagnosed with diabetic foot, acute myocardial infarction, and pulmonary edema, evolving with facial paresis seven days after onset of symptoms. Brain CT showed two subtle hypodensities in the basal ganglia and semiovale, probably representing small lacunar infarctions. One week later, brain CT was repeated, showing evidence of multiple irregular hypodensities bilaterally in the periventricular deep white matter and the bilateral basal ganglia, in addition to a large area of hypodensity in the corpus callosum. MRI showed multiple bilateral lesions in the frontal region and the corpus callosum, as well as in the temporal and parietal regions and occipital lobes, with restriction on the diffusion, consistent with acute infarction.

The last patient reported by Arabi et al. (2015), who also had severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, received peginterferon alpha-2b and ribavirin. He evolved to persistent coma and multiple organ failure. Brain CT did not show acute abnormality; however, MRI showed hyperintensity (T2WI/FLAIR) in the white matter in both hemispheres of the brain and along the corticospinal tract. The patient was diagnosed with encephalitis.

Arabi et al. (2015) highlight the importance of beginning examining the neurological manifestations of CoVs due to their evident neurotropism. The great importance of the comorbidities attributed to these patients is known; in conjunction with severe acquired diseases, these findings may have been caused by other etiologies. However, the CSF of two patients showed evidence of increased protein, even when negative for MERS-CoV. In addition, the MRI findings had distinct patterns associated with other hypoxic-ischemic pathologies, viral etiologies being rather favorable, such as ADEM, which has already been described in other viral agents. Furthermore, vascular accidents have already been associated with other viral etiologies, such as varicella and HIV, making it conceivable that these are associated with MERS-CoV. In this study, laboratory examinations showed leukopenia with lymphopenia, and two patients died.

Kim et al. (2017) also affirmed the virus’s neuroinvasive potential. They conducted a study with 23 clinically severe patients, with confirmed diagnosis, undergoing treatment for MERS-CoV. All patients received triple antiviral treatment with interferon alpha-2a, high-dose ribavirin, and lopinavir/ritonavir. Four died, and another four (17.4 %) had neurological complications. Median age was 46 years, with one patient having previous comorbities. Neurological alterations were both motor and sensory. Only one of the four patients with neurological complications required mechanical ventilation. This patient presented ptosis and drowsiness, with limb ataxia, quadriparesis, and general hyporeflexia, with brain MRI and CSF within the parameters of normality. Probable diagnosis was Bickerstaff’s encephalitis (BBE) with differential diagnosis of GBS. Another patient developed mild crural paresis and hyporeflexia in the lower limbs, with diagnosis of infectious or toxic polyneuropathy. The other two patients reported sensory alterations in their members, with likely diagnosis of acute sensory neuropathy.

It is worth emphasizing that all patients almost completely recovered from their symptoms after neurological treatment, and structural alterations were not seen after imaging examinations. Furthermore, neurological complications were delayed; they did not appear concomitantly with respiratory symptoms, but rather around 2–3 weeks later. One study limitation was the evaluation of the presence of the virus in the CSF, which was performed in only one patient, with a negative result. No laboratory alterations were detailed (Kim et al., 2017).

Two recently published cases indicate that the virus’s neurotropic potential caused severe neurological diseases, such as meningitis and encephalitis. Poyiadji et al. (2020) described the first presumed case of ANHE in a patient with COVID-19. ANHE has already been described as a rare complication following other viral infections such as influenza, rubella, and coxsackievirus.

The case report describes a patient who had a three-day history of fever, cough, and altered consciousness. SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed and, as a study limitation, the presence of the virus in the CSF was not tested. Brain CT demonstrated symmetric hypointensity in the thalamus. CT angiogram and venogram were within the parameters of normality, and MRI in the T2/FLAIR sequences showed hyperintensity in the bilateral medial temporal lobe and thalamus, with evidence of hemorrhage. The patient was treated with IV immunoglobulin, without the use of high-dose corticoids (Poyiadji et al., 2020).

ANHE is a fulminant encephalopathy, and it is rare, mostly affecting the pediatric age range. It is mainly characterized by symmetric lesions on the thalamus, as well as in the white fibers, the cerebellum, and the brainstem, and it has been related to cytokine storms in the CNS. According to Mehta et al. (2020), some patients with COVID-19 may develop an increase in cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-7, granulocytecolony stimulating factor, interferon-γ inducible protein 10, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α, and tumor necrosis factor-α. This central neuroinflammation may facilitate the occurrence of encephalopathies, such as ANHE (Lin et al., 2019; Mehta et al., 2020; Poyiadji et al., 2020).

Moriguchi et al. (2020) also described the first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with COVID-19. A 34-year-old patient with headache, fever, and pharyngitis evolved on the ninth day to decreased level of consciousness and epileptic crises. Neck stiffness was identified. Increased leukocytes were detected by laboratory exams. Neutrophils were dominant; lymphocytes were relatively decreased, and C-reactive protein was increased. Chest CT revealed glass opacity, and brain MRI showed hyperintensities in the wall of the lateral ventricle and a hyperintense signal in the mesial temporal lobe and hippocampus with mild atrophy, indicating pneumonia, ventriculitis, and encephalitis, respectively. In this case, SARS-COV2 was negative on the nasopharyngeal swab but positive in the CSF.

5. Conclusion

COVID-19 is a common pathology that may affect diverse organs, including the central and peripheral nervous system. The neurological symptoms caused by CoV are similar, and they may affect any age group; the main symptoms are headache (16.8 %), dizziness (13.9 %), and altered consciousness (11.2 %). New studies should be conducted with a focus on neurological alterations, which may be severe and may further compromise patients’ clinical profiles. We have, furthermore, observed that CoV infection in the CNS leads to expression of multiple cytokines with possible impairment of the immune system, emphasizing the virus’s neurotropic capacity.

Ethical aspects

This study was carried out in accordance with the ethical aspects.

Study funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure

A.O. Correia, P.W.G. Feitosa, J.L.S. Moreira, S.A.R. Nogueira, R.B. Fonseca and M.E.P. Nobre report no relevant dosclosures.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Arabi Y.M., Harthi A., Hussein J., Bouchama A., Johani S., Hajeer A.H.…Balkhy H. Severe neurologic syndrome associated with Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus (MERS-CoV) Infection. 2015;43(4):495–501. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M.D., Taub D.D., Perry V.H. Overriding the brain’s intrinsic resistance to leukocyte recruitment with intraparenchymal injections of recombinant chemokines. Neuroscience. 1996;74(1):283–292. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Wu D., Chen H., Yan W., Yang D., Chen G., Ma K., Xu D., Yu H., Wang H., Wang T., Guo W., Chen J., Ding C., Zhang X., Huang J., Han M., Li S., Luo X.…Ning Q. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: Retrospective study. Bmj. 2020;1091(December 2019):m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd D.A., Giddings T.H., Kirkegaard K. Poliovirus 3A protein limits Interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and Beta interferon secretion during viral infection. Journal of Virology. 2001;75(17):8158–8165. doi: 10.1128/jvi.75.17.8158-8165.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplanski G., Teysseire N., Farnarier C., Kaplanski S., Lissitzky J.C., Durand J.M.…Bongard P. IL-6 and IL-8 production from cultured human endothelial cells stimulated by infection with Rickettsia conorii via a cell-associated IL-1α-dependent pathway. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;96(6):2839–2844. doi: 10.1172/JCI118354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.E., Heo J.H., Kim H.O., Song S.H., Park S.S., Park T.H.…Choi J.P. Neurological complications during treatment of middle east respiratory syndrome. Journal of Clinical Neurology (Korea) 2017;13(3):227–233. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2017.13.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.C., Bai W.Z., Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may be at least partially responsible for the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020;(February):24–27. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li H., Fan R., Wen B., Zhang J., Cao X.…Liu W. Coronavirus infections in the central nervous system and respiratory tract show distinct features in hospitalized children. Intervirology. 2017;59(3):163–169. doi: 10.1159/000453066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.Y., Lee K.Y., Ro L.S., Lo Y.S., Huang C.C., Chang K.H. Clinical and cytokine profile of adult acute necrotizing encephalopathy. Biomedical Journal. 2019;42(3):178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., Hu Y., Chen S., He Q.…Hu B. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. The Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi T., Harii N., Goto J., Harada D., Sugawara H., Takamino J., Ueno M., Sakata H., Kondo K., Myose N., Nakao A., Takeda M., Haro H., Inoue O., Suzuki-Inoue K., Kubokawa K., Ogihara S., Sasaki T., Kinouchi H.…Shimada S. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. International Journal of Infectious Diseases: IJID. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyiadji N., Shahim G., Noujaim D., Stone M., Patel S., Griffith B. COVID-19–associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology. 2020;2(2001):5–10. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin A.R. 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: A review of the current literature. Eurasian Journal of Medicine and Oncology. 2020 doi: 10.14744/ejmo.2020.12220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Xu X., Chen Z., Duan J., Hashimoto K., Yang L.…Yang C. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin C. Genotyping coronavirus SARS-CoV-2: Methods and implications. ArXiv.Org. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.04.016. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.10965v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Cao D., Zhang Y., Ma J., Qi J., Wang Q.…Gao G.F. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nature Communications. 2017;8:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15092. (China CDC) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li J., Zhan Y., Wu L., Yu X., Zhang W.…Lou J. Analysis of serum cytokines in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(8):4410–4415. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4410-4415.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]