Abstract

Aims

Adequate health insurance coverage is necessary for heart transplantation (HT) candidates. Prior studies have suggested inferior outcomes post HT with public health insurance. We sought to evaluate the effects of insurance type on transplantation rates, listing status and mortality prior to HT.

Methods and results

Patients ≥18 years old with a left ventricular assist device implanted and listed with 1A status were identified in the United Network for Organ Sharing registry between January 2010 and December 2017, with follow‐up through March 2018. Patients were grouped based on the type of insurance private/self‐pay (PV), Medicare (MC), and Medicaid (MA) at the time of listing. We conducted multivariable competing risks regression analysis on listing status and mortality on the waiting list, stratified by insurance type at the time of listing. We identified 2604 patients listed in status 1A (PV: 51.4%, MC: 32.1%, and MA: 16.5%). MA patients were younger (43.5 vs. 56.4 for MC vs. 51.5 for PV, P < 0.001) and less frequently White (P < 0.001). The cumulative incidence of HT did not differ among the three insurance types (PV: 74.8%, MC 76.3%, and MA 71.1%, P = 0.14). The cumulative mortality on the waiting list prior to HT was not different among groups (PV: 29.3%, MC 26.3%, and MA 21.8%, P = 0.94). Μore patients with MA were removed from the list because of improvement of their condition (MA 40.3% vs. MC 28.3% and PV 32.8%).

Conclusions

We did not detect any disparities in listing status and mortality among different insurance types.

Keywords: LVAD, Insurance, Heart transplantation

Introduction

Heart transplantation (HT) is the preferred treatment option for patients with refractory stage D heart failure. Despite cardiac (cardiac allograft vasculopathy) and non‐cardiac barriers (infections and malignancies) to long‐term survival, outcomes of HT recipients continue to improve steadily over the past 30 years with 1‐year survival exceeding 85% and median survival of 11 years for adult recipients.1 The observed improvements in survival of HT recipients is due to better donor and recipient selection, advances in immunosuppression, development of multidisciplinary transplant teams, and prompt identification and treatment of cardiac and non‐cardiac complications. However, the ongoing shortage of donors is the main barrier to HT; hence, wait‐list mortality remains a problem despite a decline in wait‐list mortality since 2005 because of the use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs).2, 3

According to the three‐tier donor allocation system prior to October 2018 created by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), status code 1A is designated for listed candidates requiring mechanical circulatory support (30 days after LVAD implantation or with LVAD malfunction and complications such as thromboembolism, infection, ventricular arrhythmias and aortic regurgitation, total artificial heart, and temporary mechanical circulatory support), continuous mechanical ventilation, or continuous infusion of multiple inotropes in addition to haemodynamic monitoring.4 As of 18 October 2018, a new allocation system became effective5 aiming to reduce wait‐list mortality, to limit the number of exemptions to high priority statuses, and to ensure fair allocation of organs to the sickest candidates. The prior status 1A is now divided into three new statuses 1, 2, and 3.

HT is an option for patients with adequate health insurance coverage. A significant number of patients have public insurance (Medicare or Medicaid), and these programmes are crucial for eligibility to HT and post HT care for those candidates that cannot afford private insurance programmes. Although access to public health insurance is critical for vulnerable populations, earlier studies have raised concerns about higher mortality, rates of rejection, and decreased graft survival with Medicare/Medicaid compared with private insurances6, 7, 8 not only for HT recipients but also for other solid organ transplant recipients.9, 10 Transition from private to public insurance after HT is also associated with worse outcomes whereas transition for private insurance is related to improved outcomes.11 Potential adverse impact of public health insurance on outcomes post HT is attributed to limited access to post‐transplant care and limited coverage of immunosuppression therapy.12

The characteristics and outcomes of continuous‐flow LVAD recipients listed as status 1A based on insurance status are not well described. Therefore, we used a multicentre nationally representative data set to (i) evaluate the incidence of HT among different insurance types, (ii) evaluate the reasons for list removal, and (iii) assess mortality on the waiting list among adults with LVADs listed as 1A status for HT.

Methods

The UNOS database registry follows all prospective candidates listed for organ transplantation, documenting any change in status and date of any transplant. The registry records additional clinical information at the time of transplant and continues to follow the recipient post transplant. Registry data include standard demographic, clinical, and laboratory information at the time of listing, as well as the patient's priority to receive an organ, known as the UNOS status.

Candidates ≥18 years of age with an implanted LVAD and 1A status for heart transplant from January 2010 to December 2017 with follow‐up through March 2018 were included. These patients were grouped into the following categories based on type of insurance at time of listing: private/self‐pay (PV), Medicare (MC), and Medicaid (MA). Among 109 183 patients listed for HT during the study period, we excluded patients less than 18 years old (n = 9176), those who underwent transplantation before 2010 (n = 48 774) as they were more likely to have a first generation pulsatile flow device, those not in status 1A (n = 43 756), and those in status 1A not supported by a durable LVAD. Patients with other forms of insurance status including foreign government payment (n = 94) were excluded from the study.

The main outcomes were cumulative incidence of heart transplant, mortality on the waiting list prior to heart transplant, and removal from the waiting list prior to transplant because of clinical deterioration or improvement such that transplant is no longer appropriate.

Statistical analysis

Patients were classified based on insurance status at listing into private/self‐pay, Medicare, and Medicaid. We compared baseline characteristics between the three groups using χ 2‐test test for categorical variable and Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variable. Reasons for removal from waiting list were reported as percentages after stratification by insurance status. We then evaluated the association between insurance status at listing and two pre‐specified outcomes—mortality and transplant—in separate analyses. Because the occurrence of one of the outcomes will prevent the other from manifesting, we accounted for this by use of competing risks regression, according to the model of Fine and Gray. Variables that were adjusted for include age, gender, race, body mass index, diabetes, prior cardiac surgery, dialysis‐dependent, cerebrovascular disease, and presence of an implanted defibrillator. For transplant analysis, occurrence of mortality prior to transplant was included in the model as a competing event and vice versa. All analyses were performed using STATA 15 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) with level of significance set at 0.05.

Results

We identified a total of 2604 adults (PV: 51.4%, MC: 32.1%, and MA: 16.5%) with an LVAD listed as 1A status for HT from January 2010 to December 2017. The patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. MA patients were younger (43.5 vs. 56.4 for MC vs. 51.5 for PV, P < 0.001) and less frequently White (38.69% vs. 60.76% for MC vs. 68.15% for PV, P < 0.001). MC patients were more likely to be male patients (80.50% vs. 74.13% for MA vs. 77.70% for PV, P = 0.03) and diabetic (38.88% vs. 24.01% for MA vs. 28.15% for PV, P < 0.001). They were more likely to have an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (84.62% vs. 68.24% for MA vs. 68.14% for PV, P < 0.001) and prior cardiac surgery (60.05% vs. 50.58% for MA vs. 51.26% for PV, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of left ventricular assist device patients listed as status 1A according to insurance type

| Patient characteristics | Private (n = 1339) | Medicare (n = 836) | Medicaid (n = 429) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 51.5 (12.4) | 56.4 (1.4) | 43.5 (12.9) | <0.001 |

| Male, % | 77.70 | 80.50 | 74.13 | 0.03 |

| White, % | 68.15 | 60.76 | 38.69 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 27.5 (5.0) | 28.7 (5.0) | 27.9 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 28.15 | 38.88 | 24.01 | 0.00 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, % | 5.85 | 7.60 | 6.31 | 0.27 |

| ICD, % | 68.14 | 84.62 | 68.24 | 0.00 |

| Dialysis dependent | 4.59 | 2.85 | 4.66 | 0.10 |

| Prior cardiac surgery, % | 51.26 | 60.05 | 50.58 | 0.00 |

| Mean PAP | 28.9 (10.7) | 28.4 (10.6) | 28.5 (10.5) | 0.52 |

| Mean PCWP | 19.8 (9.6) | 18.4 (9.4) | 18.9 (10.0) | 0.01 |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 4.5 (1.5) | 4.5 (1.3) | 4.5 (1.4) | 0.44 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 1.0 (1.6) | .94 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.9) | 0.77 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.3 (0.81) | 1.3 (0.77) | 1.2 (0.59) | 0.00 |

| PRA class 1, % | 31.77 | 31.92 | 38.22 | 0.28 |

| PRA class 2, % | 23.29 | 24.43 | 31.41 | 0.11 |

BMI, body mass index; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PRA, panel reactive antibodies; SD, standard deviation.

Median time from LVAD implantation to listing was 132 for PV, 232 for MC, and 157 for MA, and median time to transplantation was 251 days for PV, 353 days for MC, and 297 days for MA. At the time of transplantation, 84% of PV, 87.9% of MC, and 75.5% of MA maintained their insurance type, whereas 11.5% of PV transitioned to MC, 7.7% of MC to PV, and 16.3% of MA to MC (Table 2). During the study period, the rates of PV decreased from 58% of listed LVAD patients to 46% in 2017. The rates of MC patients increased from 25% in 2010 to 37% in 2017. The rates of MA remained relatively stable and less than 20% from 2010 to 2017. The trends of insurance coverage are depicted in Figure 1 .

Table 2.

Transitions to different insurance types between listing an transplantation

| Insurance status at transplantation | Insurance status at the time of listing | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Private (n = 979) | Medicaid (n = 624) | Private (n = 294) | |

| Private (n = 900) | 828 (84.5%) | 48 (7.7%) | 24 (8.2%) |

| Medicare (n = 710) | 113 (11.5%) | 549 (87.9%) | 48 (16.3%) |

| Medicaid (n = 287) | 38 (3.8%) | 27 (4.3%) | 222 (75.5%) |

% in parenthesis represent percentage of each group at listing. Insurance status was missing for ~28% of the patients at transplant.

Figure 1.

Trends of insurance type from 2010 to 2017.

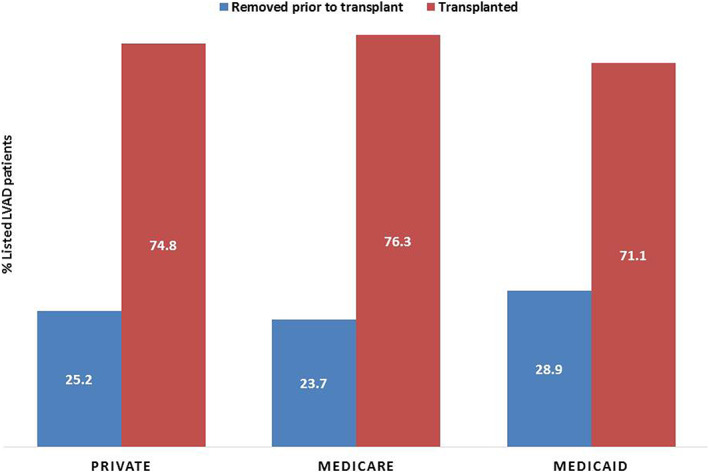

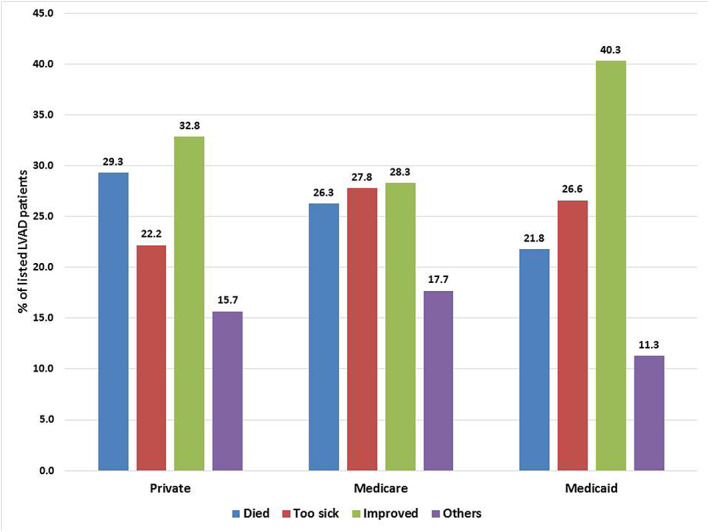

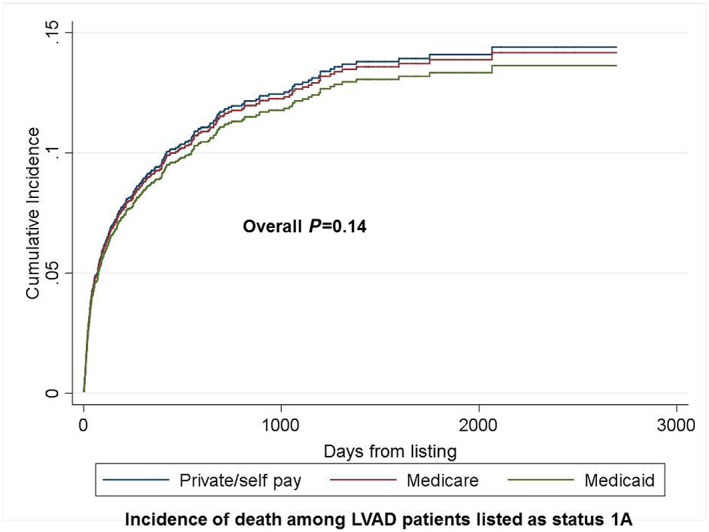

As shown in Figure 2 , the cumulative incidence of heart transplant was similar among the three insurance types (PV: 74.8%, MC 76.3%, and MA 71.1%, P = 0.14). A numerically higher portion of MA patients were removed from the wait list prior to HT compared with MC and PV (28.9% vs. 23.7% vs. 25.2%, respectively). Multivariate regression analysis suggested that the cumulative incidence of HT did not differ significantly among groups as displayed on Figure 3 [MC: sub‐hazard ratio (SHR) = 1.1, 95% confidence intervals (CI) = 0.98–1.2, P = 0.08 with PV as reference; and MA: SHR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85–1.1, P = 0.71 with PV as reference]. With regard to reasons for the removal of 660 patients prior to HT, more patients with MA were removed from the list because of improvement of their condition (MA 40.3% vs. MC 28.3% vs. PV 32.8%), and more patients with PV were removed from the list because of death (PV 29.3%, MC 26.3%, and MA 21.8%; Figure 4 ). Among PV patients, a numerically lower percentage was removed because of being too sick for HT (PV 22.2%, vs. MC 27.8% vs. MA 26.6%). The cumulative mortality on the waiting list prior to HT was not different among the groups (PV: 29.3%, MC 26.3%, and MA 21.8%, P = 0.94; MC: SHR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.75–1.2, P = 0.9 with PV as reference; and MA: SHR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.67–1.3, P = 0.73 with PV as reference, Figure 5 ).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of transplantation among left ventricular assist device patients listed as status 1A.

Figure 3.

Rates of patients who were transplanted or removed from transplant list, stratified by insurance status.

Figure 4.

Reasons for removal of 660 patients prior to transplant, stratified by insurance status.

Figure 5.

Cumulative incidence of death among left ventricular assist device patients listed as status 1A.

Discussion

The salient findings of this analysis of insurance coverage among LVAD recipients listed as status 1A in the previous allocation system from a nationally representative multicentre database can be summarized as follows: (i) approximately half of these patients have public health insurance coverage (Medicare or Medicaid) with the rates of MC increasing and those of PV coverage decreasing during the study period; (ii) Medicare HT candidates tend to be older male patients with higher body mass index and higher rates of prior cardiac surgery while Medicaid patients were younger and less likely Whites; (iii) more Medicaid patients were removed from the wait list, mainly because their status improved, whereas more HT candidates with private insurance coverage died on the wait list; (iv) overall, the incidence of HT was similar among groups; and (v) wait‐list mortality was not different among the three types of insurance coverage.

Socio‐economic disparities exist among HT recipients and affect outcomes post transplantation. Patients at lower socio‐economic status are more likely Medicare or Medicaid beneficiaries and less likely privately insured.13 Furthermore, the recent analysis of UNOS registry on 33 893 adult heart transplant recipients between 1994 and 2014 suggested increased risk of death or retransplantation associated with public health insurance status.13 Among patients younger than 65 years, Medicare coverage has increased significantly during the past 20 years to approximately 30%, whereas Medicaid coverage rates have remained stable and private insurance coverage has decreased, similar to the findings of our analysis.13, 14 The reason for increased Medicare coverage is the eligibility of an increasing number of stage D heart failure patients for long‐term disability benefits (at least 2 years). These data show a concerning signal of worse outcomes in an era of increased federal support for HT. Federal support is also important for LVAD recipients as Medicare and Medicaid consistently contributed to >50% of total costs of LVAD hospitalizations.15 A previous UNOS analysis of LVAD recipients listed for HT between 2004 and 2014 demonstrated that patients at higher socio‐economic status had increased risk of death on the wait list during LVAD support because of higher burden of comorbidities and clinical acuity, but those at lower socio‐economic status had an early and sustained decreased post‐transplant survival.16 The consistent evidence of worse outcomes post HT is unlikely due to sicker recipients or inferior quality donor hearts as suggested by previous analyses and confirmed by our findings. Instead, public health insurance coverage of immunosuppression medications may be challenging for many of HT recipients who do not work full time because of disability, as the copayment for these medications is higher compared with anticoagulation used during LVAD support.17 Moreover, frequent follow‐up for surveillance of rejection and levels of immunosuppressive medications, optimization of non‐immunologic risk factors for cardiac allograft vasculopathy, and early screening for malignancies can be challenging for patients with limited access to health care and can certainly impact long‐term outcomes.

The finding of worse outcomes with public health insurance was not confirmed by our analysis of status 1A recipients with LVADs. Plausible explanations for this are the following: (i) surgical and post‐implantation outcomes of patients with continuous flow LVADs have improved over time, and socio‐economic status should not be considered as a risk factor for mortality. In fact, in a recent single‐centre study, lower socio‐economic status was associated with decreased risk of death in the unadjusted analysis, and the association became non‐significant after adjustment for clinically relevant comorbidities18. (ii) Socio‐economic disparities are narrowing over time the role of multidisciplinary teams in identifying barriers to health‐care access, and assist with medication coverage has been crucial in the improvement of outcomes after observed in the last 20 years.19 iii) Patients at higher listing status often receive the highest level of care and attention with frequent visits and hospitalizations; hence, socio‐economic status may become less of a barrier in these cases. However, the lack of substantial differences in wait‐list mortality and HT incidence does not mean that public insurance coverage does not affect long‐term outcomes post HT. The new allocation system for HT will allow patients in higher clinical acuity status to be transplanted, and these patients may need more health‐care resources during their recovery. Furthermore, the recent increase in HT volume in the United States and the observed trends of increased dependency of HT patients on federal support, especially in younger patients with long‐term disability, mandate scrutinization of enrolment and improved access to public health insurance especially for the sicker HT candidates eligible for higher listing statuses. Also, previously reported barriers to coverage of immunosuppressive medications under Medicare20 should be addressed to prevent risk of graft dysfunction from medication non‐adherence.

The findings of our study should be interpreted in the context of certain limitations, including the retrospective analysis design of a registry database, the quality of the source data, and the differences in practices followed in the participating centres. Furthermore, the causes of death on the waiting list and specifics of medical and device therapy of listed patients were not available in the database. Also, patients with worsening condition may have been removed from the transplant list and this can lead to underestimation of mortality.

In conclusion, approximately half of LVAD recipients listed as status 1A have public health insurance coverage, which did not affect the incidence of transplantation and wait‐list mortality.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Briasoulis, A. , Akintoye, E. , Inampudi, C. , Hammoud, A. , and Alvarez, P. (2020) The impact of insurance type on listing status and wait‐list mortality of patients with left ventricular assist devices as bridge to transplantation. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 804–810. 10.1002/ehf2.12655.

References

- 1. Lund LH, Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Goldfarb S, Kucheryavaya AY, Levvey BJ, Meiser B, Rossano JW, Chambers DC, Yusen RD, Stehlik J, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation . The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty‐fourth adult heart transplantation report‐2017; Focus theme: allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017; 36: 1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Colvin M, Smith JM, Hadley N, Skeans MA, Carrico R, Uccellini K, Lehman R, Robinson A, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL. OPTN/SRTR 2016 annual data report: heart. Am J Transplant 2018; 18: 291–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colvin M, Smith JM, Hadley N, Skeans MA, Uccellini K, Lehman R, Robinson AM, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL. OPTN/SRTR 2017 annual data report: heart. Am J Transplant 2019; 19: 323–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network . Administrative rules and definitions https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/policies/ (accessed on 15th October 2019).

- 5. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network . Allocation of hearts and heart‐lungs https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2412/adult_heart_approved_policy_language.pdf (accessed on 15th October 2019).

- 6. DuBay DA, MacLennan PA, Reed RD, Shelton BA, Redden DT, Fouad M, Martin MY, Gray SH, White JA, Eckhoff DE, Locke JE. Insurance type and solid organ transplantation outcomes: a historical perspective on how medicaid expansion might impact transplantation outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 2016; 223: 611–620.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Allen JG, Weiss ES, Arnaoutakis GJ, Russell SD, Baumgartner WA, Shah AS, Conte JV. Insurance and education predict long‐term survival after orthotopic heart transplantation in the United States. J Heart Lung Transplant 2012; 31: 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breathett K, Willis S, Foraker RE, Smith S. Impact of insurance type on initial rejection post heart transplant. Heart Lung Circ 2017; 26: 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allen JG, Arnaoutakis GJ, Orens JB, McDyer J, Conte JV, Shah AS, Merlo CA. Insurance status is an independent predictor of long‐term survival after lung transplantation in the United States. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011; 30: 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldfarb‐Rumyantzev AS, Koford JK, Baird BC, Chelamcharla M, Habib AN, Wang BJ, Lin SJ, Shihab F, Isaacs RB. Role of socioeconomic status in kidney transplant outcome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1: 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tumin D, Foraker RE, Smith S, Tobias JD, Hayes D Jr. Health insurance trajectories and long‐term survival after heart transplantation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2016; 9: 576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tumin D, McConnell P, Galantowicz M, Tobias JD, Hayes D Jr. Reported Nonadherence to immunosuppressive medication in young adults after heart transplantation: a retrospective analysis of a national registry. Transplantation 2017; 101: 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wayda B, Clemons A, Givens RC, Takeda K, Takayama H, Latif F, Restaino S, Naka Y, Farr MA, Colombo PC, Topkara VK. Socioeconomic disparities in adherence and outcomes after heart transplant. Circ Heart Fail 2018; 11: e004173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeFilippis EM, Vaduganathan M, Machado S, Stehlik J, Mehra MR. Emerging trends in financing of adult heart transplantation in the United States. JACC Heart Fail 2019; 7: 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel N, Kalra R, Doshi R, Bajaj NS, Arora G, Arora P. Trends and cost of heart transplantation and left ventricular assist devices: impact of proposed federal cuts. JACC Heart Fail 2018; 6: 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clerkin KJ, Garan AR, Wayda B, Givens RC, Yuzefpolskaya M, Nakagawa S, Takeda K, Takayama H, Naka Y, Mancini DM, Colombo PC. Impact of socioeconomic status on patients supported with a left ventricular assist device: an analysis of the UNOS database (United Network for Organ Sharing). Circ Heart Fail 2016; 9: e003215.27758810 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evans R. An actuarial perspective on the annual per patient maintenance immunosuppressive medication costs for transplant recipients: 1993‐2011. Am J Transplant 2013; 13: 270–271. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clemons AM, Flores RJ, Blum R, Wayda B, Brunjes DL, Habal M, Givens RC, Truby LK, Garan AR, Yuzefpolskaya M, Takeda K, Takayama H, Farr MA, Naka Y, Colombo PC, Topkara VK. Effect of socioeconomic status on patients supported with contemporary left ventricular assist devices. ASAIO J 2019. 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001009 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. Cajita MI, Baumgartner E, Berben L, Denhaerynck K, Helmy R, Schönfeld S, Berger G, Vetter C, Dobbels F, Russell CL, de Geest S, BRIGHT Study Team . Heart transplant centers with multidisciplinary team show a higher level of chronic illness management‐findings from the International BRIGHT Study. Heart Lung 2017; 46: 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Potter LM, Maldonado AQ, Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Zhang Z, Hess GP, Garrity E, Kasiske BL, Axelrod DA. Transplant recipients are vulnerable to coverage denial under Medicare Part D. Am J Transplant 2018; 18: 1502–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]