Abstract

Aim

According to guidelines, a prognosis should be discussed with all heart failure (HF) patients. However, many patients do not have these conversations with a healthcare provider. The aim of this study was to describe attitudes of cardiologists in Sweden and the Netherlands regarding this topic.

Methods and results

A survey was sent to 250 cardiologists in Sweden and the Netherlands with questions whether should the prognosis be discussed, what time should the prognosis be discussed, whom should discuss, what barriers were experienced and how difficult it is to discuss the prognosis (scale from 1–10). A total of 88 cardiologists participated in the study. Most cardiologists (82%) reported to discussing the prognosis with all HF patients; 47% at the time of diagnoses. The patient's own cardiologist, another cardiologist, the HF nurse, or the general practitioner could discuss this with the patient. Important barriers were cognitive problems (69%) and a lack of time (64%). Cardiologists found it not very difficult to discuss the topic (mean score 4.2) with a significant difference between Swedish and Dutch cardiologist (4.7 vs. 3.7; P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Most cardiologists found it important to discuss the prognosis with HF patients although there are several barriers. Swedish cardiologists found it more difficult compared with their Dutch colleagues. A multidisciplinary approach seems important for improvement of discussing prognosis with HF patients.

Keywords: Communication, Heart failure, Palliative care, Prognosis

1. Introduction

International guidelines and guidance documents recommend that prognosis should be discussed with heart failure (HF) patients.1, 2, 3 However, many patients do not have these conversations4 and have poorer understanding of their prognosis compared with patients with lung cancer.5 Most patients prefer doctors to initiate these conversations; however, healthcare providers often wait until the patient ask questions about their prognosis.6

In a previous study, HF patients reported that professionals provided patients with little information regarding prognosis and that the communication was mainly focused on HF management.7

A survey among 274 HF nurses in Sweden and the Netherlands8, 9 showed that 63–69% of the nurses reported that the cardiologist should have the responsibility to discuss the prognosis with their patient, although 19% also found it a shared responsibility of doctor and HF nurse. The question raises what the attitude of cardiologists is regarding this topic. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe attitudes of cardiologists on discussing prognosis with HF patients with a focus on barriers and how difficult they experience these conversations.

2. Methods

A total of 275 HF cardiologists (150 in Sweden and 125 in the Netherlands) were invited by email to participate in a survey. The names and email addresses of the cardiologists were retrieved through the Swedish network of cardiologists (RiksSvikt) and the National Society of Cardiology in the Netherlands (Nederlandse Vereniging voor Cardiologie). After 4 weeks, a reminder was send by email.

The questionnaire was adapted from a previously used questionnaire developed for HF nurses in Sweden and the Netherlands.8 Prognosis in this study was defined as ‘the expected trajectory of a disease in a specific individual’. The cardiologists were asked to complete a 10‐item questionnaire about communicating prognosis, including nine predefined possible barriers in these discussions. They also were asked to select a time point in the disease trajectory when they would discuss prognosis for the first time with the following possible answers: ‘at time diagnosis was assessed’, ‘first period of decompensated HF’, ‘second period of decompensated HF’, ‘in case of a serious decrease of the condition’, or ‘just before end of life’. Furthermore, they were asked whether they thought if patients would be upset when prognosis was discussed with them with possible answers ‘always’, ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘seldom’, or ‘never’. Finally, they were asked to rate their experienced difficulty with discussing prognosis on a scale from 1 (not difficult at all) to 10 (very difficult). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample; t‐tests and chi‐square tests were performed to assess differences between the groups.

3. Results

A total of 88 cardiologists (43 in the Netherlands; 45 in Sweden; response rate 34%) completed the questionnaire (mean age 51 ± 9; 23% women).

3.1. Timing and responsibility

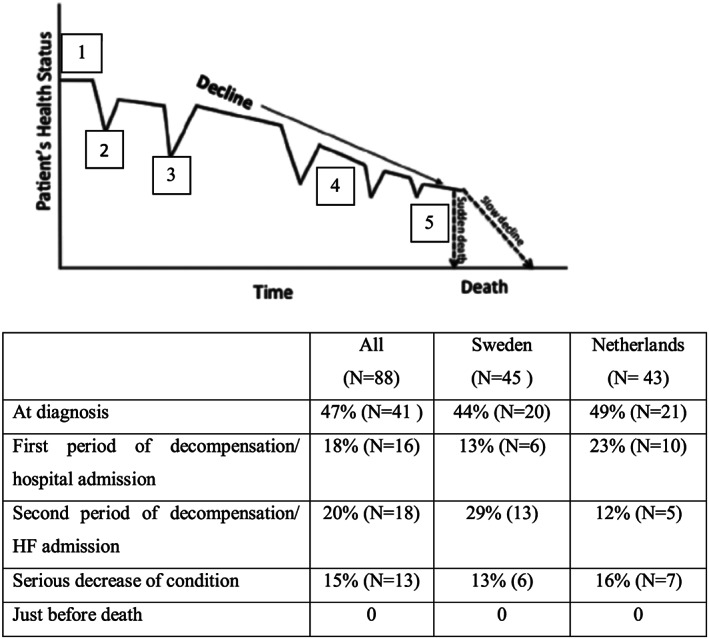

Most cardiologists (82%) reported that prognosis should be discussed with all HF patients somewhere in the disease trajectory. Regarding timing of the discussion, 47% of the cardiologist stated that prognosis should be discussed at the time of diagnosis, although 18% found the first period of decompensated HF or HF hospitalization the best time to discuss it with the patient. Sixteen percent wanted to discuss the prognosis only in case of a serious decrease in the HF condition (Figure 1 ). There were no significant differences in time points to discuss the prognosis between Swedish and Dutch cardiologists.

Figure 1.

Preferred time to discuss prognosis with heart failure patients.

Almost all participants (97%) stated that the discussion about prognosis should be initiated by the patient's own cardiologist, but 65% also reported that another cardiologist, the HF nurse (51%), or the general practitioner (28%) could discuss this with the patient.

3.2. Barriers

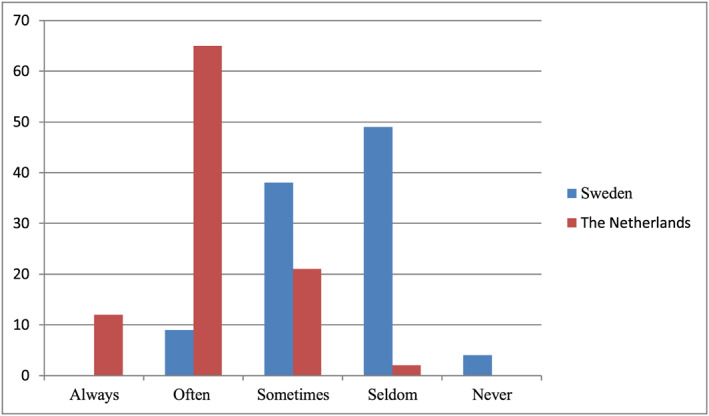

A total of 36% reported that patients would be upset often with a significant difference between the Netherlands and Sweden (65% vs. 9%; P < 0.01) (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

To what extent the cardiologists believed that patients would be upset if prognosis was discussed with them.

The most‐reported barriers to discuss prognosis were cognitive problems of the patient (69%), a lack of time (64%), and that the patient was not ready for it (60%). Other important barriers were the unpredictability of the disease (53%) and fear that the patient would be worried or lose hope (50%), with no significant differences between Sweden and the Netherlands (Table 1).

Table 1.

Barriers to discuss prognosis with heart failure patients

| Barriers | Cardiologists (N = 88) |

|---|---|

| Cognitive problems | 69% (61) |

| Lack of time | 64% (56) |

| Patient not ready for it | 60% (53) |

| Unpredictable course of heart failure | 53% (47) |

| Fear patient is worried/would lose hope | 50% (44) |

| Family not ready for it | 39% (34) |

| Several comorbidities | 36% (32) |

| Low educational level | 28% (25) |

| Do not know how to talk about it | 7% (6) |

| Other reasons | 35% (31) |

Although the mean reported difficulty in discussing prognosis was rather low (4,2 ± 2), about a quarter of the participants rated >6. Swedish cardiologists reported a higher rate in difficulty in discussing prognosis compared with Dutch participants (4.7 vs. 3.7; p < .05).

4. Discussion

Most of the participating cardiologists in this survey (82%) reported that it is important to discuss the prognosis with their HF patients during the disease trajectory and did not think it was very difficult to discuss this. However, almost one out of five cardiologists stated that it is not necessary to discuss this with all of their HF patients.

Important barriers to discussing the prognosis were both related to the patient or their condition (cognitive problems and unpredictability of HF), to the environment (not enough time), or the perception of the cardiologist (afraid of taking away hope). This last reason was also reported in other studies.4, 8, 10 Hope, however, can be seen as a positive future orientation, and is not necessarily associated with cure, but also with hope for better moments or for a good death, in accordance with patient's own values and beliefs.11

In an earlier survey on discussing prognosis among HF nurses in Sweden,8 it was found that nurses more often reported the unpredictability as most important barrier to discuss prognosis compared with cardiologists in our study (77 vs. 53%).

Both a considerable number of cardiologists in the current study (64%) and HF nurses (52%) in the previous study reported that lack of time was an important barrier to discussing the prognosis.

Our survey showed that only 7% of the cardiologists reported that it was very difficult to discuss the prognosis with their patients. In a survey among cardiology clinicians in the US, it was found that almost 20% of the participants (N= 95) reported low or very low confidence in discussing prognosis with HF patients,10 and 30% did not feel well equipped to discuss advance care planning with HF patients and their family. It was found earlier that knowledge and confidence to discuss difficult subjects, for example sex, can be important.12

The difference between these studies might be partly explained by a possible response bias in our study with cardiologists who were positive regarding this topic responded more often than their colleagues who were more reluctant to discuss prognosis with their patients.

Because knowledge or confidence does not seem to be the most important barrier to discussing the prognosis with HF patients, providing more education would not be sufficient. Structural changes such as providing more time or communication tools (for example a question prompt list) might be more effective to improve the discussion about the prognosis with all HF patients.

The response rate of 34% limits generalizability, and probably, it were those who are already interested in the subject that responded.

5. Conclusion

Most cardiologists in this survey did not find it difficult to discuss prognosis with their HF patients and suggested it should be discussed at the time of diagnosis. Barriers to discussing the prognosis were related to the patient (cognitive problems and not being ready for it), to the organization (lack of time), or to the healthcare provider (afraid of taking away hope). Most cardiologists reported that the patient's own cardiologist should discuss the prognosis with the patient, although also other health care providers (cardiologist on the ward, HF nurse, and general practitioner) could discuss this. Therefore, a multidisciplinary team approach using appropriate communication tools, seems important to improve discussing prognosis with HF patients.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from FORTE [2017‐02227]

Declaration of Interest

For all authors: none declared.

van der Wal, M. H. L. , Hjelmfors, L. , Strömberg, A. , and Jaarsma, T. (2020) Cardiologists' attitudes on communication about prognosis with heart failure patients. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 878–882. 10.1002/ehf2.12672.

References

- 1. Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M, Rutten FH, McDonagh T, Mohacsi P, Murray SA, Grodzicki T, Bergh I, Metra M, Ekman I, Angermann C, Leventhal M, Pitsis A, Anker SD, Gavazzi A, Ponikowski P, Dickstein K, Delacretaz E, Blue L, Strasser F, McMurray J. Advanced Heart Failure Study Group of the HFA of the ESC. Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009; 11: 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur J Heart Fail. 2016; 18: 891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Diepen S, Katz JN, Albert NM, Henry TD, Jacobs AK, Kapur NK, Kilic A, Menon V, Ohman EM, Sweitzer NK, Thiele H, Washam JB, Cohen MG. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; and Mission: Lifeline. Contemporary management of cardiogenic shock: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017; 17: e232–e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, Seamark D, Parker C, Gariballa S, Small N. Communication in heart failure: perspectives from older people and primary care professionals. Health Soc Care Community. 2006; 14: 482–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth A, Benton TF, Clausen H. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. BMJ. 2002; 325: 929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barclay S, Momen N, Case‐Upton S, Kuhn I, Smith E. End‐of‐life care conversations with heart failure patients: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011; 61: e49–e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hjelmfors L, Sandgren A, Strömberg A, Mårtensson J, Jaarsma T, Friedrichsen M. ‘I was told that I would not die from heart failure’: patient perceptions of prognosis communication. Appl Nurs Res. 2018; 41: 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hjelmfors L, Strömberg A, Friedrichsen M, Mårtensson J, Jaarsma T. Communicating prognosis and end‐of‐life care to heart failure patients: a survey of heart failure nurses' perspectives. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014; 13: 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van der Wal MHL, Hjelmfors L, Strömberg A, Jaarsma T. Nurses perspectives on discussing prognosis and end‐of‐life in heart failure patients in the Netherlands (abstract ESC 2014)

- 10. Dunlay SM, Foxen JL, Cole T, Feely MA, Loth AR, Strand JJ, Wagner JA, Swetz KM, Redfield MM. A survey of clinician attitudes and self‐reported practices regarding end‐of‐life care in heart failure. Palliat Med. 2015; 29: 260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davidson PM, Dracup K, Phillips J, Daly J, Padilla G. Preparing for the worst while hoping for the best: the relevance of hope in the heart failure illness trajectory. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007; 22: 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jaarsma T, Strömberg A, Fridlund B, De Geest S, Mårtensson J, Moons P, Norekval TM, Smith K, Steinke E. Thompson DR; UNITE research group. Sexual counselling of cardiac patients: Nurses' perception of practice, responsibility and confidence. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010; 9: 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]