Abstract

Aims

The assessment of frailty in older adults with heart failure (HF) is still debated. Here, we compare the predictive role and the diagnostic accuracy of physical vs. multidimensional frailty assessment on mortality, disability, and hospitalization in older adults with and without HF.

Methods and results

A total of 1077 elderly (≥65 years) outpatients were evaluated with the physical (phy‐Fi) and multidimensional (m‐Fi) frailty scores and according to the presence or the absence of HF. Mortality, disability, and hospitalizations were assessed at baseline and after a 24 month follow‐up. Cox regression analysis demonstrated that, compared with phy‐Fi score, m‐Fi score was more predictive of mortality [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.05 vs. 0.66], disability (HR = 1.02 vs. 0.89), and hospitalization (HR = 1.03 vs. 0.96) in the absence and even more in the presence of HF (HR = 1.11 vs. 0.63, 1.06 vs. 0.98, and 1.14 vs. 1.03, respectively). The area under the curve indicated a better diagnostic accuracy with m‐Fi score than with phy‐Fi score for mortality, disability, and hospitalizations, both in absence (0.782 vs. 0.649, 0.763 vs. 0.695, and 0.732 vs. 0.666, respectively) and in presence of HF (0.824 vs. 0.625, 0.886 vs. 0.793, and 0.812 vs. 0.688, respectively).

Conclusions

The m‐Fi score is able to predict mortality, disability, and hospitalizations better than the phy‐Fi score, not only in absence but also in presence of HF. Our data also demonstrate that the m‐Fi score has better diagnostic accuracy than the phy‐Fi score. Thus, the use of the m‐FI score should be considered for the assessment of frailty in older HF adults.

Keywords: Multidimensional frailty, Older adults, Heart failure

Introduction

In older adults, heart failure (HF) is a public health problem whose importance is likely to grow in the coming years because of the progressive increase in survival of patients with cardiac diseases. 1 , 2 However, in HF patients, the prognosis is worse in the elderly, with higher mortality, both inhospital and long term. 1 , 2 The incidence of hospitalization for HF in older adults is also increasing, exceeding 70% of total hospital admissions. 1 , 2 Age‐related cardiac diseases, together with ageing processes, worsen the clinical manifestations of HF in older adults. 3

According to most definitions, frailty is a clinical state in which an individual is more vulnerable to developing dependency and/or mortality when exposed to a stressor. 4 In 2001, Fried and colleagues focused on a physical phenotype of frailty based on the assessment of unintentional weight loss, muscle weakness, slow walking speed, low physical activity, and exhaustion (phy‐Fi). 5 On the other hand, Rockwood and colleagues developed a concept of multidimensional frailty involving co‐morbidity, disability, psychological, and social components, along with physical impairments (frailty index). 6

Although there is a significant amount of data on the association between frailty and HF in older adults, so far the approach to the problem has not been conclusive. 7 Specifically, there has been inconsistency in the assessment of the type of frailty especially when considering physical or multidimensional phenotype. 7 , 8 In older HF patients, frailty is frequently identified with physical frailty, which is only one of the aspects of clinical frailty; this can often lead to a prognostic underestimation. 8 , 9 In order to approach multidomain frailty, an Italian version of the frailty index (m‐Fi), modified by adding the assessment of nutritional and socio‐economic statuses (which represent critical points in the management of HF patients), has been recently published. 10

Thus, the present study aimed at prospectively comparing the diagnostic accuracy of multidimensional (m‐Fi) and physical (phy‐Fi) frailty assessment in predicting mortality, disability, and hospitalization in elderly HF patients.

Methods

Study population

We enrolled 1077 elderly (≥65 years) subjects consecutively admitted to the ‘Geriatric Evaluation outpatients Unit' of Federico II University Hospital (Naples, Italy). The study received full ethical approval according to the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. All participants signed an informed consent form, and the institutional review boards approved the study. Neither patients nor the public was involved in the design, conduct, reporting, and dissemination of our research.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

The study population underwent a comprehensive geriatric assessment that included the following: anthropometric measurements, such as body mass index; physiological, pathological, and pharmacological anamnesis; cognitive function evaluation with Mini Mental State Examination; depression screening with geriatric depression scale; co‐morbidity evaluation with a cumulative illness rating scale (CIRS‐Comorbidity and CIRS‐Severity); assessment of drugs burden; disability with basic (BADL) and instrumental activity of daily living; physical performance with 4 m gait speed; physical activity with physical activity scale for the older adults; nutritional state with mini nutritional assessment; social support evaluation with social support scale [scored from 17 (participants with the lowest support) to 0 (participants with the highest support)], and Tinetti mobility test.

Biochemical assessment

C‐reactive protein (CRP), BNP (pg/mL), and glomerular filtration rate (mg/dL) were assessed at baseline.

Multidimensional frailty assessment

Multidimensional frailty (m‐Fi) was assessed using a 40 item tool, previously validated in Italian older adult outpatients from the Campania Region (Italy). 9 Briefly, this tool has been adapted from the Canadian frailty index and explores the four domains of frailty: physical, mental, nutritional, and socio‐economic. 11 The m‐Fi differs from the Canadian frailty index for the nutritional domain, assessed with the mini nutritional assessment, and the socio‐economic domain, evaluated with the social support scale. Accordingly, patients were stratified by m‐Fi score in lightly (0.1–16), moderately (16.1–27.0), and severely (>27.0) frail (see references in Supporting Information).

Physical frailty assessment

Physical frailty (phy‐Fi score) 5 was calculated by considering the following items of m‐Fi score: the need for help when lifting 10 lbs, a weight loss of more than 10 lbs over the previous year, a decrease of physical activity over the past months, the sensation that everyday living is an effort, and 4 m gait speed <10 s) (8). Accordingly, patients were stratified by phy‐Fi score in lightly (1–2), moderately (3), and severely (>3) frail.

Heart failure diagnosis

The diagnosis of HF was considered possible when the subjects reported: (i) a medical diagnosis of HF, (ii) a specific treatment for HF (beta blockers, ace‐inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers, diuretics, and digitalis), (iii) signs of HF (dyspnoea, lung rales, and/or pretibial oedema), or (iv) anamnestic presence of clinical or radiographic findings of cardiomegaly or pulmonary oedema or ventricular dilatation and abnormalities of ventricular kinetics assessed by echocardiography. The specific aetiology of HF was determined and confirmed according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and BNP, when available. 12

Outcomes

Mortality, disability (defined as ≥1 BADL lost from the baseline), and hospitalizations were assessed at baseline and after 24 months of follow‐up.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected and analysed using SPSS software (version 13.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Characteristics of the sample are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Participants were stratified by degree of multidimensional and physical frailty (light, moderate, and severe) and according to the presence or absence of HF. ANOVA test with Bonferroni's post hoc correction was performed to compare continuous variables across groups. Differences between continuous variables, divided according to the presence or absence of HF, were analysed by means of Student's t‐test. Differences among dichotomous data were analysed using the χ 2 test. Logistic regression was used to examine receiving operating characteristics curves to compare the performance of multidimensional (m‐Fi) vs. physical frailty in predicting the outcomes; area under curves (AUC) between 0.8 and 0.9 was considered good. Multivariate Cox regression analysis and survival curves, adjusted for age and sex, were used to evaluate the predictive value of physical (phy‐Fi) and multidimensional (m‐Fi) and in the presence and absence of HF on mortality and disability and hospitalization. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Out of the 1077 study participants, 12 were excluded because they did not present any degree of frailty, while 158 were lost at follow‐up. The 907 enrolled elderly subjects were divided based on the presence or absence of HF and stratified according to m‐Fi and phy‐Fi frailty scores (Tables 1 and 2 ).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population stratified by physical (phy‐Fi) and multidimensional (m‐Fi) frailty score in absence of heart failure

| Variables | All | Frailty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Moderate | Severe | |||||

| phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | ||

| n = 717 (79.1%) | 161 (22.5%) | n = 247 (34.4%) | 296 (41.3%) | n = 231 (32.2%) | 260 (36.3%) | n = 239 (33.3%) | |

| Age (years) | 81.3 ± 6.5 | 79.5 ± 6.3 | 79.8 ± 6.7 | 80.1 ± 6.4 | 81.8 ± 6.1 | 82.2 ± 6.3 | 82.4 ± 6.2 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 283 (39.5) | 59 (57.5) | 127 (51.4) | 127 (51.4) | 79 (35.4) | 113 (30.8) | 77 (32.2) |

| BMI | 27.1 ± 4.9 | 26.4 ± 3.3 | 26.6 ± 3.9 | 27.6 ± 5.2 | 27.4 ± 5.5 | 27.6 ± 5.1 | 27.7 ± 5.4 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 576 (80.3) | 60 (58.6) | 174 (70.4) | 205 (83.0) | 186 (83.4) | 311 (84.7) | 216 (90.4) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 170 (23.7) | 19 (18.0) | 56 (22.7) | 69 (27.9) | 46 (20.6) | 82 (22.4) | 68 (28.5) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 185 (25.8) | 16 (9.9) | 49 (19.8) * | 64 (21.6) | 78 (33.8) * | 105 (40.4) | 90 (37.7) |

| CIRS‐C score | 3.6 ± 2.0 | 2.5 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 1.9 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 1.9 | 4.4 ± 1.9 |

| BADL lost | 1.8 ± 1.8 | 1.5 ± .1.9 | 0.5 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 3.3 ± 1.6 * |

| NYHA II–III, n (%) | 176 (24.5) | 10 (10) | 25 (10.1) | 59 (24.0) | 68 (30.5) | 106 (29.0) | 83 (34.7) |

| LVEF ≤45%, n (%) a | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| BNP (pg/mL) b | 282 ± 410 | 200 ± 310 | 354 ± 310 | 262 ± 220 | 565 ± 730 | 342 ± 140 | 530 ± 420 |

| GFR (mL/min) c | 68.5 ± 21.4 | 71.2 ± 14.6 | 68.8 ± 20.2 | 65.2 ± 21.8 | 61.2 ± 11.6 | 58.8 ± 16.4 | 52.4 ± 12.8 |

| Drugs (n) | 5.6 ± 2.9 | 4.7 ± 2.9 | 5.5 ± 2.8 | 5.8 ± 2.7 | 5.7 ± 2.8 | 6.2 ± 2.9 | 6.2 ± 3.1 |

| CRP (mg/dL) a | 0.64 ± 0.50 | 0.38 ± 0.40 | 0.50 ± 0.42 | 0.40 ± 0.48 | 0.65 ± 0.40 | 0.48 ± 0.42 | 0.51 ± 0.40 |

| m‐Fi, score | 20.4 ± 9.1 | 7.0 ± 6.4 | 8.7 ± 5.5 | 16.6 ± 6.9 | 20.1 ± 6.4 | 25.0 ± 5.7 | 28.1 ± 4.3 * |

| Fried's score | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 1.0 |

BADL, basic activity of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CIRS‐C, cumulative index rating scale–quantity; CRP, C‐reactive protein; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

P < 0.05 vs. phy‐Fi.

Echocardiography was available in 68.0% of participants (n = 488).

BNP was available in 37.0% of participants (n = 265).

GFR was available in 86.0% of participants (n = 617).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study population stratified by physical (phy‐Fi) and multidimensional (m‐Fi) frailty score in presence of heart failure

| Variables | Frailty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Moderate | Severe | |||||

| phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | ||

| n = 190 (20.9%) | n = 31 (16.3%) | n = 45 (23.7%) | n = 78 (41.1%) | n = 67 (35.3%) | n = 81 (42.6%) | n = 78 (41.1%) | |

| Age (years) | 81.5 ± 6.4 | 78.8 ± 7.3 | 79.7 ± 7.3 | 82.2 ± 6.8 | 81.5 ± 5.9 | 81.1 ± 6.2 | 82.3 ± 6.2 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 105 (55.3) * | 20 (85.0) | 37 (82.2) | 46 (72.7) | 32 (47.8) * | 40 (38.6) | 36 (46.2) * |

| BMI | 28.2 ± 7.8 | 30.3 ± 10.7 | 27.6 ± 5.6 | 28.36 ± 5.0 | 27.6 ± 5.2 | 26.1 ± 4.4 | 25.3 ± 11.1 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 168 (88.4) * | 22 (95.0) | 41 (91.1) | 54 (83.6) | 56 (83.6) | 93 (90.0) | 71 (81.6) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 102 (53.7) * | 14 (60) | 30 (66.7) | 34 (53.0) | 31 (46.3) * | 54 (52.3) | 41 (47.1) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 71 (37.7) | 11 (35.5) | 19 (42.2) * | 21 (26.9) | 28 (41.8) * | 39 (48.1) | 78 (48.7) |

| CIRS‐C score | 4.8 ± 2.5 * | 5.4 ± 5.4 | 4.6 ± 3.9 | 4.5 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 2.0 | 5.0 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 2.0 * |

| BADL lost | 2.2 ± 2.0 * | 0.8 ± 1.7 | 0.7 ± 1.4 | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 2.8 ± 1.9 | 3.5 ± 1.6 * |

| NYHA II–III, n (%) | 169 (88.9) * | 20 (85.0) | 39 (87.0) | 56 (88.0) | 59 (88.0) | 93 (90.0) | 71 (91.0) |

| LVEF ≤45%, n (%)† | 127 (66.8) * | 8 (35.0) | 17 (38.0) | 38 (60.0) | 46 (69.0) | 80 (78.0) | 64 (82.0) * |

| BNP (pg/mL) b | 572 ± 620 * | 300 ± 420 * | 362 ± 520 | 452 ± 420 * | 654 ± 410 | 520 ± 420 * | 765 ± 630 * |

| GFR (mL/min) c | 41.4 ± 11.6 * | 48.6 ± 18.6 | 65.3 ± 28.2 | 51.2 ± 10.4 | 55.2 ± 14.6 | 45.2 ± 16.4 | 38.0 ± 16.6 |

| Drugs (n) | 7.8 ± 3.0 * | 7.9 ± 2.7 | 8.4 ± 2.9 | 7.2 ± 3.1 | 7.5 ± 3.2 | 8.8 ± 3.1 | 8.1 ± 3.1 |

| CRP (mg/dL) a | 0.95 ± 0.30 * | 0.35 ± 0.40 | 0.51 ± 0.57 | 0.38 ± 0.34 | 0.60 ± 0.48 | 0.44 ± 0.38 | 1.10 ± 0.50 * |

| m‐Fi, score | 23.3 ± 7.7 * | 12.1 ± 4.4 | 12.1 ± 2.9 | 22.5 ± 6.2 | 22.2 ± 3.1 * | 28.3 ± 4.8 | 30.7 ± 2.4 * |

| Fried's score | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 1.3 * |

BADL, basic activity of daily living; BMI, body mass index; CIRS‐C, cumulative index rating scale–quantity; CRP, C‐reactive protein; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

P < 0.05 vs. phy‐Fi.

Echocardiography was available in 72.0% of participants (n = 137).

BNP was available in 41.0% of participants (n = 78).

GFR was available in 88.0% of participants (n = 167).

Among patients without HF (79.1%), stratification by frailty showed a higher prevalence of light frailty when the assessment was performed according to m‐Fi score compared with phy‐Fi score (34.4% vs. 22.5%, respectively), while a higher prevalence of severe frailty was observed when the assessment was performed according to phy‐Fi score than when compared with m‐Fi score (36.3% vs. 33.3%, respectively). In severely frail subjects, mortality, disability, and hospitalization rates were higher when frailty was assessed by m‐Fi score rather than by phy‐Fi score (36.8% vs. 25.0%, 88.5% vs. 80.0%, and 78.2% vs. 63.6%, respectively) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Outcomes observed in the study population stratified by physical (phy‐Fi) and multidimensional (m‐Fi) frailty score in absence and in presence of heart failure (HF)

| Outcomes | Frailty | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Moderate | Severe | |||||

| phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | phy‐Fi | m‐Fi | ||

| No HF | n = 717 (79.1%) | 161 (22.5%) | n = 247 (34.4%) | 296 (41.3%) | n = 231 (32.2%) | 260 (36.3%) | n = 239 (33.3%) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 84 (11.7) | 6 (5.7) | 2 (0.8) | 23 (9.5) | 14 (6.3) | 55 (15.0) | 68 (28.5) * |

| Disability, n (%) | 448 (62.4) | 45 (43.7) | 108 (43.7) | 143 (57.7) | 155 (69.5) | 261 (71.0) | 185 (77.4) * |

| Hospitalizations, n (%) | 246 (34.3) | 16 (16.0) | 48 (19.4) | 60 (24.3) | 63 (28.3) | 169 (46.1) | 135 (56.5) * |

| HF | n = 190 (20.9%) | n = 31 (16.3%) | n = 45 (23.7%) | n = 78 (41.1%) | n = 67 (35.3%) | n = 81 (42.6%) | n = 78 (41.1%) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 39 (20.5) | 2 (9.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (17.0) | 7 (10.4) | 26 (25.0) | 32 (36.8) * |

| Disability, n (%) | 150 (78.9) | 17 (72.0) | 19 (42.2) | 51 (79.0) | 54 (80.6) | 82 (80.0) | 77 (88.5) * |

| Hospitalizations, n (%) | 104 (54.7) | 7 (30.0) | 12 (26.7) | 31 (49.0) | 24 (35.8) | 66 (63.6) | 68 (78.2) |

P < 0.05 vs. phy‐Fi.

In HF patients (20.1%), cardiac co‐morbidities, such as the prevalence of hypertension and coronary artery disease and, more importantly, extra‐cardiac co‐morbidities represented by CIRS‐C score, BADL lost, medication burden, and CRP values, were significantly higher than in no HF patients. Interestingly, m‐Fi score (23.7 ± 7.7 vs. 20.4 ± 9.1), but not phy‐Fi score (3.0 ± 1.5 vs. 2.7 ± 1.5), was significantly higher in HF patients.

As expected, all end points considered (mortality, disability, and hospitalizations) were significantly higher in HF than in no HF patients (Table 3 ). In addition, severely frail subjects had higher CIRS‐C score and CRP levels when frailty was assessed by m‐Fi score rather than by phy‐Fi score. Interestingly, while assessment by m‐Fi score included more subjects with reduced LVEF and increased BNP values into severe frailty, the prevalence of New York Heart Association class II–III subjects did not show significant differences between the two assessment tools (90.0% vs. 91.0%). HF patients with higher BNP levels (n = 78/190, 41%) presented more adverse events in presence of severe than in presence of light frailty, both when assessed with phy‐Fi score (28.5% vs. 5.0% for mortality, 81.0% vs. 70.0% for disability, and 68.0% vs. 25.0% for hospitalizations) or with m‐Fi score (40.0% vs. 0.0% for mortality, 90.0% vs. 39.5% for disability, and 81.0% vs. 24.0% for hospitalizations). In addition, significant differences were observed in mortality, disability, and hospitalizations in severely frail subjects when assessed by the m‐Fi score with respect to those assessed by phy‐Fi score (36.8% vs. 25.0%, 88.5% vs. 80.0%, and 78.2% vs. 63.6%, respectively) (Table 3 ).

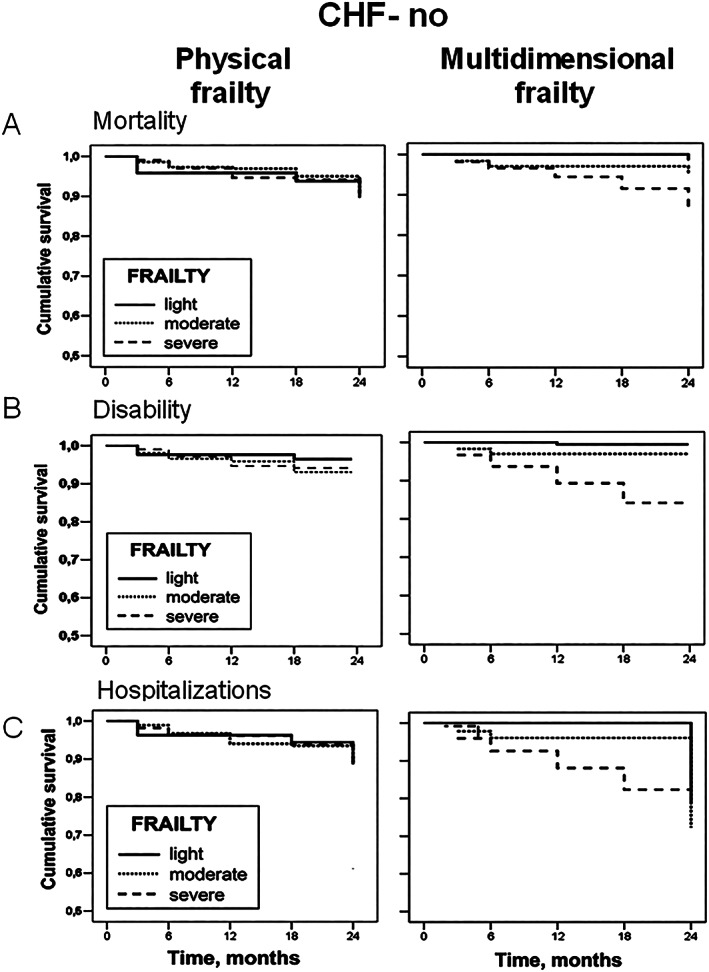

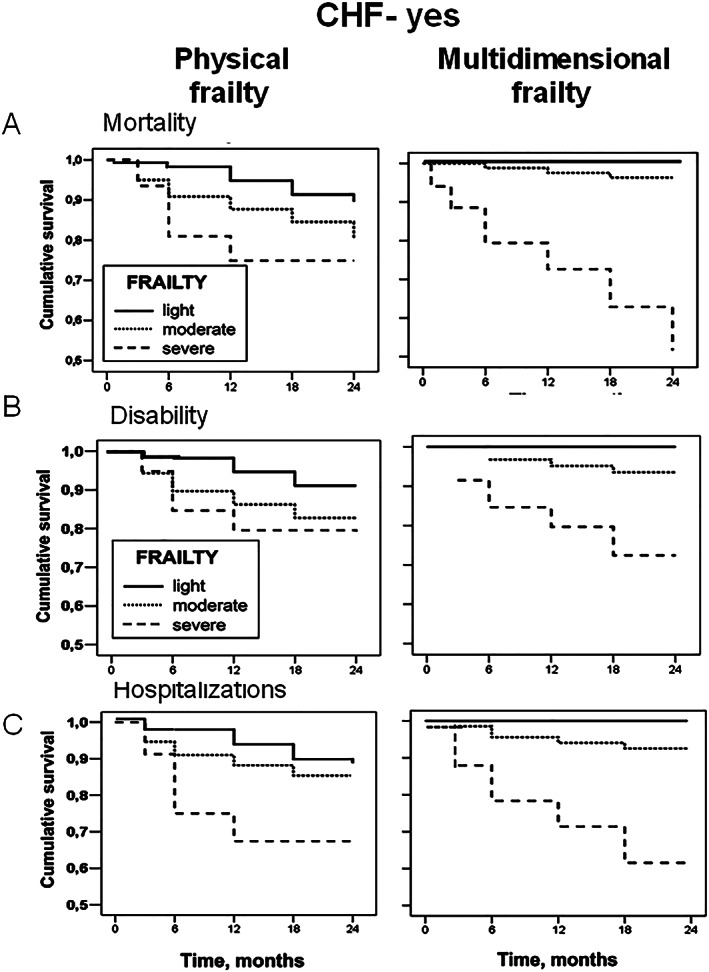

To compare the performance of m‐Fi and phy‐Fi scores in predicting outcomes, Cox regression analyses on mortality, disability, and hospitalization were performed for both tools. Figures 1 and 2 show the ability of m‐Fi and phy‐Fi scores to predict events in the absence and the presence of HF, while Table 4 reports the hazard ratios (HRs) derived from Cox regression analysis, adjusted for age and sex. The analysis showed that, when compared with phy‐Fi score, m‐Fi score is more powerful in predicting mortality (HR: 1.05 vs. 0.66), disability (HR: 1.02 vs. 0.89), and hospitalization (HR: 1.03 vs. 0.96) in absence and even more in presence of HF (mortality: HR: 1.11 vs. 0.63; disability: HR: 1.06 vs. 0.98; hospitalization: HR: 1.03 vs. 1.14) (Figures 1 and 2 ).

Figure 1.

Cox regression survival curves, adjusted for age and sex, of physical and multidimensional frailty on mortality (A), disability (B), and hospitalizations (C) in elderly patients outpatients in absence of heart failure (no HF) stratified according to the degree of frailty (light, moderate, and severe). CHF, chronic heart failure.

Figure 2.

Cox regression survival curves, adjusted for age and sex, of physical and multidimensional frailty on mortality (A), disability (B), and hospitalizations (C) in elderly HF patients stratified according to the degree of frailty (light, moderate, and severe). CHF, chronic heart failure.

Table 4.

Area under the curve in patients without and with heart failure (HF) stratified by physical (phy‐Fi) and multidimensional (m‐Fi) frailty scores

| No HF | HF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | ||||||

| Frailty | Area | 95% CI | P | Area | 95% CI | P |

| phy‐fi | 0.649 | 0.584–0.713 | <0.001 | 0.625 | 0.520–0.729 | 0.017 |

| m‐Fi | 0.782 | 0.739–0.826 | <0.001 | 0.824 | 0.766–0.881 | <0.001 |

| Disability | ||||||

| Frailty | Area | 95% CI | P | Area | 95% CI | P |

| phy‐fi | 0.695 | 0.653–0.736 | <0.001 | 0.793 | 0.720–0.865 | <0.001 |

| m‐Fi | 0.763 | 0.725–0.800 | <0.001 | 0.886 | 0.835–0.936 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalizations | ||||||

| Frailty | Area | 95% CI | P | Area | 95% CI | P |

| phy‐fi | 0.666 | 0.625–0.706 | <0.001 | 0.688 | 0.613–0.763 | <0.001 |

| m‐Fi | 0.732 | 0.694–0.770 | <0.001 | 0.812 | 0.750–0.875 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval.

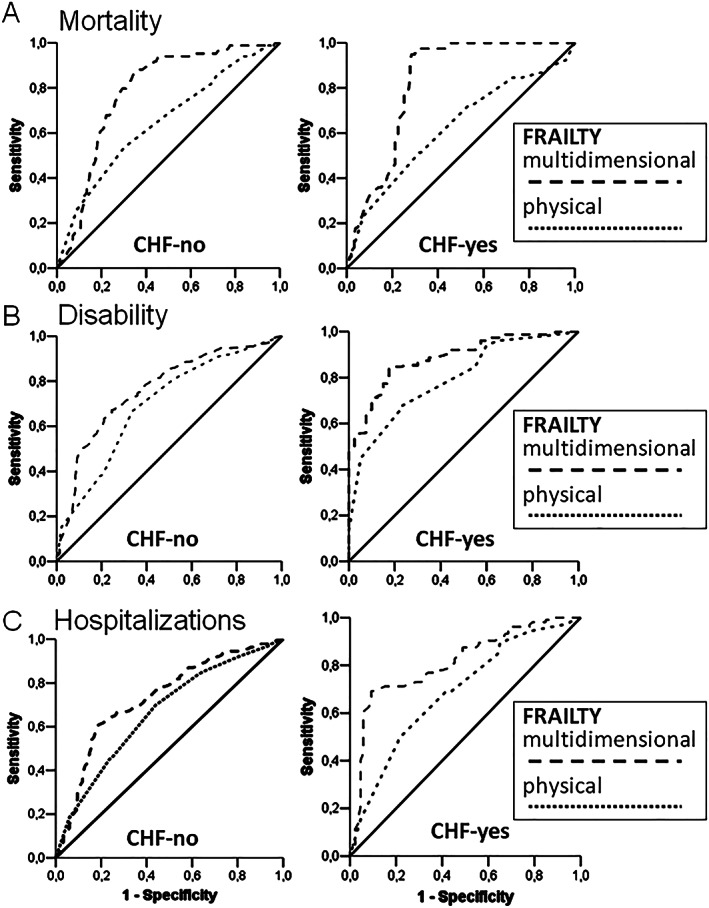

Figure 3 shows receiving operating characteristics curves for m‐Fi and phy‐Fi scores on mortality, disability, and hospitalizations either in absence (left panels) or in presence (right panels) of HF. Accordingly, AUCs values with m‐Fi score are better than phy‐Fi score for mortality, disability, and hospitalizations both in absence (0.782 vs. 0.649, 0.763 vs. 0.695, and 0.732 vs. 0.666) and in presence of HF (0.824 vs. 0.625, 0.886 vs. 0.793, and 0.812 vs. 0.688) (see Table 5 ).

Figure 3.

Area under curves analysis of physical and multidimensional frailty on mortality (A), disability (B), and hospitalizations (C) in elderly patients in absence (no HF) and in presence (HF) of heart failure. CHF, chronic heart failure.

Table 5.

Cox regression analysis adjusted for age and sex in patients without and with heart failure (HF) stratified by physical (phy‐Fi) and multidimensional (m‐Fi) frailty scores

| No HF | HF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | ||||||

| Frailty | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| phy‐Fi score | 0.66 | 0.51–1.05 | 0.127 | 0.63 | 0.43–1.07 | 0.214 |

| m‐Fi score | 1.05 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.04 | 1.11 | 1.03–1.18 | <0.05 |

| Disability | ||||||

| Frailty | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| phy‐Fi score | 0.89 | 0.77–1.16 | 0.202 | 1.15 | 0.77–1.72 | 0.472 |

| m‐Fi score | 1.02 | 1.01–1.07 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 1.02–1.09 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalizations | ||||||

| Frailty | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P |

| phy‐Fi score | 0.96 | 0.82–1.13 | 0.666 | 1.02 | 0.74–1.39 | 0.888 |

| m‐Fi score | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.004 | 1.14 | 1.05–1.18 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

Our data indicate that the m‐Fi score is able to predict outcomes in absence and, more importantly, in presence of HF better than the phy‐Fi score. Accordingly, the m‐Fi score shows better AUCs than the phy‐Fi score for mortality, disability, and hospitalizations, both in absence and in presence of HF. Thus, the m‐Fi score appears to be more accurate in identifying and defining frailty in older adults with HF.

Frailty assessment in heart failure

Heart failure is a significant and growing public health problem worldwide, with high morbidity, mortality, and economic and social costs. 1 , 2 , 3 Indeed, HF implies peculiar clinical characteristics in older adults. 3 A large population‐based study recently reported that HF patients are characterized by co‐morbidity and inadequate nutritional and socio‐economic status. 3 These ‘geriatric' traits represent features of the HF population, which often have not been considered in HF management and profoundly affect patients outcomes. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Indeed, these aspects represent the multidomain of frailty and need to be better characterized in older HF adults. 9

Although frailty is becoming one of the most critical issues in public health, its assessment remains unclear. 20 Fried et al. first defined the frailty phenotype as a condition not directly associated with a specific disease or disability, but rather with reduced physical performance, and defined by the presence of three or more of five criteria: involuntary weight loss, muscle weakness, slow walking, asthenia, and reduced physical activity. 5 In contrast, the “multidimensional” frailty has been defined as a clinical condition associated with known co‐morbidity, disability, malnutrition, and negative psychosocial components. 6 , 21 Both frailty definitions have been related to adverse outcomes. 22

In a recent meta‐analysis, the prevalence of the frailty phenotype in HF patients ranged from 19% to 77%, while multidimensional frailty ranged from 15% to 89% of the studied populations suggesting a significant heterogeneity, and consequently, a poor specificity of the assessment. 10 More recently, Zhang et al. after selecting and analysing 20 manuscripts out of over 950 considered, published between 2005 and 2017, confirmed that frailty, either physical or multidimensional, is a powerful predictor of events. Indeed, they showed that frailty significantly increases the risk of all‐cause mortality (1.59‐fold) and hospital readmissions (1.31‐fold), regardless of the timing and setting of the assessment, . 22 While confirming the crucial role of frailty in HF, these findings highlight some aspects of how frailty has been studied in HF because its first description. In our opinion, the significant amount of data on the association between frailty and HF was generated starting from the lack of a clear definition of frailty leading to inconsistency and, eventually, to both underestimation and/or overestimation of the prognostic power of frailty. In fact, in our study, the prevalence of patients with severe frailty was higher, with a lower prevalence of light frailty, when assessed with phy‐Fi compared with m‐Fi, both in absence and in presence of HF.

In the present study, the new approach (m‐Fi score) based on a multidimensional concept, involving not only physical impairment but also mental, nutritional, and social components, has been compared with the physical phenotype (phy‐Fi score), previously identified as the gold standard of frailty.

Physical vs. multidimensional frailty score in the assessment of older heart failure patients

In our study, the prevalence of New York Heart Association class II–III subjects did not show significant differences between the two assessment tools, while reduced LVEF and increased BNP values were significantly more present in severely frail subjects assessed by the m‐Fi score as compared with phy‐Fi score. Indeed, the phy‐Fi score has the advantage of being relatively easy to perform but also the significant disadvantage of identifying a frail condition that weights only functional impairments. 5 On the other hand, HF is a syndrome characterized by signs and symptoms shared with several other medical conditions, which may include clinical features physical frailty. This overlapping negatively affects a reliable identification of frailty in the presence of HF, in which key symptoms are related to poor physical performance. Accordingly, when considering ‘physical' frailty in HF patients, frailty might be often blurred by HF‐related signs and symptoms. 10 In contrast, a multidimensional approach involving not only physical but also mental, nutritional, and psychosocial components could be a more appropriate tool for frailty identification. 9 , 23

Indeed, the use of a more reliable frailty assessment tool is crucial. Sze et al. compared the performances of three frailty assessment tools: one physical (Fried's) and two multidimensional (the Edmonton frailty score and the deficit Index) and showed that the physical frailty assessment tool showed high sensitivity and highest false‐positive rate with lower negative and positive predictive power in identifying frailty when compared with multidimensional tools, even if they do not report on event prediction ability. 24

Our comparison between physical and multidimensional frailty assessment tools confirms the trend to overestimate severe frailty (while underestimating light frailty) with the phy‐Fi score when compared with the m‐Fi score, especially in HF subjects. In addition, our frailty assessment was specifically performed in older HF outpatients in the absence of confounding factors because of the clinical setting and/or in clinical instability condition. It is important to highlight the importance of the timing of frailty assessment in terms of clinical stability. 9 Of course, the assessment of frailty in a condition of decompensated HF could lead to overestimating the incidence of physical frailty and eventually, its prognostic role. 25 Specifically, our results have been obtained in ‘community‐dwelling' and not in ‘institutionalized' older HF patients (i.e. nursing home), in whom the presence of an elevated degree of disability might be responsible for the high rate of misdiagnosed HF, especially in the presence of frailty. 26

Limitations of the study

Echocardiographic data were not available for all subjects. Other studies (i.e. Cardiovascular Health Study) enrolled subjects with HF according to criteria similar to the ones used in our current study (self‐report with medical record verification). 27 In particular, the authors indicated that self‐reported HF was confirmed in 73.3% of men and 76.6% of women. 27 In addition, typical HF symptoms, such as breathlessness and fatigue, present lack of specificity, and HF elderly patients may be often misclassified, especially in presence of co‐morbidities. However, as specified above, in our study, HF elderly patients were enrolled in our ‘outpatients facility' and, therefore, were mostly clinically stable and newly diagnosed HF represented only a small part of the sample.

Conclusions

The m‐Fi score is the result of a multidomain assessment, and it is able not only to identify multidimensional frailty but also to determine its degree. The m‐Fi score predicts mortality, disability, and hospitalization better than the phy‐Fi score in absence and, even more, in presence of HF. Thus, the m‐FI score may be an important tool for the assessment of frailty in elderly HF patients.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Testa, G. , Curcio, F. , Liguori, I. , Basile, C. , Papillo, M. , Tocchetti, C. G. , Galizia, G. , Della‐Morte, D. , Gargiulo, G. , Cacciatore, F. , Bonaduce, D. , and Abete, P. (2020) Physical vs. multidimensional frailty in older adults with and without heart failure. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 1371–1380. 10.1002/ehf2.12688.

References

- 1. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Colvin MM, Drazner MH, Filippatos GS, Fonarow GC, Givertz MM, Hollenberg SM, Lindenfeld J, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, Peterson PN, Stevenson LW, Westlake C. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70: 776–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P, Authors/Task Force Members; Document Reviewers . 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abete P, Testa G, Della‐Morte D, Gargiulo G, Galizia G, de Santis D, Magliocca A, Basile C, Cacciatore F. Treatment for chronic heart failure in the elderly: current practice and problems. Heart Fail Rev 2013; 18: 529–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in older adults people. Lancet 2013; 381: 752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56: M146–M156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rockwood K, Mitnitski A. Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007; 62: 722–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Afilalo J, Alexander KP, Mack MJ, Maurer MS, Green P, Allen LA, Popma JJ, Ferrucci L, Forman DE. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 747–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dent E, Kowal P, Hoogendijk EO. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Eur J Intern Med 2016; 31: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abete P, Basile C, Bulli G, Curcio F, Liguori I, Della‐Morte D, Gargiulo G, Langellotto A, Testa G, Galizia G, Bonaduce D, Cacciatore F. The Italian version of the “frailty index” based on deficits in health: a validation study. Aging Exp Clin Res 2017; 29: 913–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Testa G, Liguori I, Curcio F, Russo G, Bulli G, Galizia G, Della‐Morte D, Gargiulo G, Basile C, Cacciatore F, Bonaduce D, Abete P. Multidimensional frailty evaluation in elderly outpatients with chronic heart failure: a prospective study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019; 26: 1115–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Searle SD, Mitnitski A, Gahbauer EA, Gill TM, Rockwood K. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr 2008; 30: 8–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Denfeld QE, Winters‐Stone K, Mudd JO, Gelow JM, Kurdi S, Lee CS. The prevalence of frailty in heart failure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Cardiol 2017; 236: 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Testa G, Cacciatore F, Galizia G, Della‐Morte D, Mazzella F, Langellotto A, Russo S, Gargiulo G, De Santis D, Ferrara N, Rengo F, Abete P. Waist circumference but not body mass index predicts long‐term mortality in older adults subjects with chronic heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58: 1433–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J, Mohseni H, Hedgecott D, Perez Crespillo A, Allison M, Hemingway H, Cleland JG, McMurray JJV, Rahimi K. Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population‐based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet 2018; 391: 572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liguori I, Russo G, Aran L, Bulli G, Curcio F, Della-Morte D, Gargiulo G, Testa G, Cacciatore F, Bonaduce D, Abete P. Sarcopenia: assessment of disease burden and strategies to improve outcomes. Clin Interv Aging. 2018; 13:913–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Testa G, Della‐Morte D, Cacciatore F, Gargiulo G, D'Ambrosio D, Galizia G, Langellotto A, Abete P. Precipitating factors in younger and older adults with decompensated chronic heart failure: are they different? J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61: 1827–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rich MW, Chyun DA, Skolnick AH, Alexander KP, Forman DE, Kitzman DW, Maurer MS, McClurken JB, Resnick BM, Shen WK, Tirschwell DL, American Heart Association Older Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Stroke Council; American College of Cardiology; and American Geriatrics Society . Knowledge gaps in cardiovascular care of the older adult population: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Geriatrics Society. Circulation 2016; 24: 2103–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mazzella F, Cacciatore F, Galizia G, Della‐Morte D, Rossetti M, Abbruzzese R, Langellotto A, Avolio D, Gargiulo G, Ferrara N, Rengo F, Abete P. Social support and long‐term mortality in the elderly: role of comorbidity. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010; 51: 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin H, Zhang H, Lin Z, Li X, Kong X, Sun G. Review of nutritional screening and assessment tools and clinical outcomes in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2016; 21: 549–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Onder G, Vetrano DL, Marengoni A, Bell JS, Johnell K, Palmer K, Optimising Pharmacotherapy through Pharmacoepidemiology Network (OPPEN) . Accounting for frailty when treating chronic diseases. Eur J Intern Med 2018; 56: 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vitale C, Jankowska E, Hill L, Piepoli M, Doehner W, Anker SD, Lainscak M, Jaarsma T, Ponikowski P, Rosano GMC, Seferovic P, Coats AJ. Heart Failure Association/European Society of Cardiology position paper on frailty in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 1299–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang Y, Yuan M, Gong M, Tse G, Li G, Liu T. Frailty and clinical outcomes in heart failure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018; 19: 1003–1008.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gorodeski EZ, Goyal P, Hummel SL, Krishnaswami A, Goodlin SJ, Hart LL, Forman DE, Wenger NK, Kirkpatrick JN, Alexander KP, Geriatric Cardiology Section Leadership Council, American College of Cardiology . Domain management approach to heart failure in the geriatric patient: present and future. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 1921–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sze S, Pellicori P, Zhang J, Weston J, Clark AL. Identification of frailty in chronic heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2019; 7: 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ahmed A, Allman RM, Aronow WS, DeLong JF. Diagnosis of heart failure in older adults: predictive value of dyspnea at rest. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2004; 38: 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fung E, Hui E, Yang X, Lui LT, Cheng KF, Li Q, Fan Y, Sahota DS, Ma BHM, Lee JSW, Lee APW, Woo J. Heart failure and frailty in the community‐living elderly population: what the UFO study will tell us. Front Physiol 2018; 9: 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Psaty BM, Kuller LH, Bild D, Burke GL, Kittner SJ, Mittelmark M, Price TR, Rautaharju PM, Robbins J. Methods of assessing prevalent cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Epidemiol 1995; 5: 270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]