Abstract

Aims

Whereas syncopal episodes are a frequent complication of cardiovascular disorders, including heart failure (HF), little is known whether syncopes impact the prognosis of patients with HF. We aimed to assess the impact of a history of syncope (HoS) on overall and hospitalization‐free survival of these patients.

Methods and results

We pooled the data of prospective, nationwide, multicentre studies conducted within the framework of the German Competence Network for Heart Failure including 11 335 subjects. Excluding studies with follow‐up periods <10 years, we assessed 5318 subjects. We excluded a study focusing on cardiac changes in patients with an HIV infection because of possible confounding factors and 849 patients due to either missing key parameters or missing follow‐up data, resulting in 3594 eligible subjects, including 2130 patients with HF [1564 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), 314 patients with heart failure with mid‐range ejection fraction, and 252 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)] and 1464 subjects without HF considered as controls. HoS was more frequent in the overall cohort of patients with HF compared with controls (P < 0.001)—mainly driven by the HFpEF subgroup (HFpEF vs. controls: 25.0% vs. 12.8%, P < 0.001). Of all the subjects, 14.6% reported a HoS. Patients with HFrEF in our pooled cohort showed more often syncopes than subjects without HF (15.0% vs. 12.8%, P = 0.082). Subjects with HoS showed worse overall survival [42.4% vs. 37.9%, hazard ratio (HR) = 1.21, 99% confidence interval (0.99, 1.46), P = 0.04] and less days alive out of hospital [HR = 1.39, 99% confidence interval (1.18, 1.64), P < 0.001] compared with all subjects without HoS. Patients with HFrEF with HoS died earlier [30.3% vs. 41.6%, HR = 1.40, 99% confidence interval (1.12, 1.74), P < 0.001] and lived fewer days out of hospital than those without HoS. We could not find these changes in mortality and hospital‐free survival in the heart failure with mid‐range ejection fraction and HFpEF cohorts. HoS represented a clinically high‐risk profile within the HFrEF group—combining different risk factors. Further analyses showed that among patients with HFrEF with HoS, known cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. age, male sex, diabetes mellitus, and anaemia) were more prevalent. These constellations of the risk factors explained the effect of HoS in a multivariable Cox regression models.

Conclusions

In a large cohort of patients with HF, HoS was found to be a clinically and easily accessible predictor of both overall and hospitalization‐free survival in patients with HFrEF and should thus routinely be assessed.

Keywords: Heart failure, Syncope, Morbidity, Mortality, Survival, Prognosis

1. Introduction

Syncopal episodes are a common medical problem in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Syncope is defined as a transient loss of consciousness due to cerebral hypoperfusion, characterized by a rapid onset, short duration, and spontaneous complete recovery—often caused by alterations in pathophysiology, for example, arrhythmia, vegetative dysregulation, or haemodynamic changes.1 All these entities are also altered in heart failure (HF).1, 2, 3 Patients suffering from HF account for nearly 1–2% of the adult population in developed countries, rising up to ≥10% among people above 70 years of age with a still very poor outcome.2, 4 Syncope associated with cardiovascular disease may have a poor prognosis.5 Hence, we sought to investigate whether the history of syncope (HoS) has an impact on the survival of patients suffering from HF.

Regarding the latest guidelines, patients with HF are mainly categorized into HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), HF with mid‐range ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) due to different underlying aetiologies, demographics, co‐morbidities, and response to therapies.2, 6 All three entities present with altered systolic left ventricle (LV) function; although the left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) remains preserved among patients with HFpEF, their prevalence and prognoses are comparable.7

Observations showed that patients with HFrEF are predominantly at risk for fatal arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death.8, 9 Data from small cohorts suggested an association of HoS of any origin with a higher burden for fatal arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death among HFrEF cohorts.10

Syncopal episodes are associated not only with arrhythmia but also with LV dysfunction—even regardless of the LVEF.11 Patients with HF with syncopal episodes show more often LV dysfunction than patients with HF without HoS. Nonetheless, a previous study examining a large HFpEF cohort suggested to evaluate the impact of syncopes especially in this population based on trends they could observe.12

Because syncopal episodes are a widespread condition with a lifetime cumulative incidence as high as 35% in the general population5, further analyses challenging these findings in a cohort of patients with HF are required.

We therefore aimed to assess the prevalence and prognostic utility of HoS in patients with HF. We hypothesized that HoS is associated with worse survival and shorter time to hospitalization in patients with HF.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

The German Competence Network for HF (CNHF) constitutes one of Europe's largest HF research programmes. Its rationale and design have been previously described.13 It is a prospective, nationwide, multicentre framework of observational cohort and interventional studies aiming to describe clinical characteristics and mechanisms leading to and accelerating HF and elucidating therapeutic implications. From the beginning of the CNHF, a uniform basic clinical dataset for all studies was complemented containing 190 predefined items that were collected by all subjects included in CNHF studies.13 This approach allows for pooled data analysis of study results. Standardized case report forms, centrally run databases with automated revision and consistency checks and development of standard operating procedures for all pertinent workflows, further support the process of high‐quality data collection and analysis.13

2.2. Study sample

From a pooled database with 11 335 subjects from the 20 prospective HF studies of the German CNHF, five studies provided details of a 10 year follow‐up (5318 subjects). One trial of those focused only in patients with an HIV infection and alterations of their cardiac function. Because this HIV only population might change our pooled cohort due to the con‐medication and potential other confounders, we excluded this study and focused on the remaining four studies with 4443 subjects (Diast‐CHF, IKARIUS, CIBIS‐Eld, and INH).14, 15, 16, 17 Here, 438 subjects were missing on follow‐up details, and 411 were not completed in key parameters (e.g. echocardiography details such as LVEF or E/e′, aortic valve stenosis, and electrocardiogram (ECG) details; for more details, see Appendix A). Therefore, we analysed 3594 subjects in total, including 2130 patients with HF (HFrEF: n = 1564, HFmrEF: n = 314, and HFpEF: n = 252) and 1464 subjects without HF, who we considered as controls.

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction was defined as the diagnosis of HF and LVEF <40%, HFmrEF as the diagnosis of HF and 40% > LVEF < 50%, and HFpEF as the diagnosis of HF and LVEF >50% at the time of study inclusion.

All studies included complied with the Declaration of Helsinki; the protocols were approved by the responsible Ethics Committees, and all patients gave written informed consent.

2.3. Endpoint

The endpoints in focus were defined as time to mortality from any cause or time to first hospitalization (hospitalization‐free survival).

Death and hospitalizations, including date and diagnoses, were documented and reported throughout all studies at personal or telephone visits. Patients who were lost to follow‐up were excluded from the analysis.

2.4. Statistical methods

Study cohort and subgroups are described by number (%) for categorical data and by mean (standard deviation) for most scale variables. For the skew distributed N terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) values, median, lower quartile, and upper quartile are presented.

We compared frequencies by χ 2 test. Inverse survival curves for mortality and hospitalization were calculated and plotted by the Kaplan–Meier method. Groups were compared by log‐rank test. Observation times were truncated at 126 months.

Searching baseline variables associated with (hospitalization‐free) survival time, we built multivariable Cox regression models. Starting with the variables from Table 1, we excluded irrelevant variables by backward selection using the Akaike information criterion. Final models were built with the variables selected that way to obtain correct estimates for the hazard ratio (HR). Odds ratios and HRs were calculated including 99% confidence interval.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the population analysed based on HF entities

| No HF | HFrEF | HFmrEF | HFpEF | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1464 | n = 1564 | n = 314 | n = 252 | N = 3594 | ||||||

| General | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| or | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % |

| or | Median | [Quartiles] | Median | [Quartiles] | Median | [Quartiles] | Median | [Quartiles] | Median | [Quartiles] |

| History of syncope | 187 | 12.8% | 234 | 15.0% | 40 | 12.7% | 23 | 25.0% | 524 | 14.6% |

| Age | 65.5 | 8.3 | 66.3 | 13.3 | 70.2 | 9.6 | 72.3 | 7.1 | 66.7 | 11.0 |

| Female sex | 758 | 51.8% | 435 | 27.8% | 82 | 26.1% | 159 | 63.1% | 1434 | 39.9% |

| BMI | 28.7 | 4.7 | 27.0 | 4.7 | 27.8 | 4.4 | 29.5 | 5.2 | 27.9 | 4.8 |

| HR (at rest, 1/min) | 71 | 12 | 74 | 13 | 73 | 13 | 68 | 12 | 72 | 12 |

| Systolic BP | 147 | 22 | 123 | 19 | 135 | 20 | 147 | 23 | 135 | 24 |

| Diastolic BP | 83 | 12 | 74 | 12 | 79 | 12 | 81 | 13 | 79 | 12 |

| Medical history | ||||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 327 | 22.3% | 480 | 30.7% | 88 | 28.0% | 67 | 26.6% | 962 | 26.8% |

| Hypertension | 1157 | 79.0% | 1066 | 68.2% | 260 | 82.8% | 230 | 91.3% | 2713 | 75.5% |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 570 | 38.9% | 872 | 55.8% | 201 | 64.0% | 147 | 58.3% | 1790 | 49.8% |

| Hyperuricaemia | 185 | 12.6% | 626 | 40.0% | 70 | 22.3% | 45 | 17.9% | 926 | 25.8% |

| Family history of MI | 182 | 12.4% | 254 | 16.3% | 50 | 15.9% | 41 | 16.3% | 527 | 14.7% |

| Smoking—No | 752 | 51.4% | 682 | 43.8% | 146 | 46.6% | 161 | 64.1% | 1741 | 48.6% |

| Ex‐smoker | 544 | 37.2% | 635 | 40.8% | 137 | 43.8% | 68 | 27.1% | 1384 | 38.6% |

| Smoker | 167 | 11.4% | 239 | 15.4% | 30 | 9.6% | 22 | 8.8% | 458 | 12.8% |

| CAD | 218 | 14.9% | 792 | 50.6% | 193 | 61.5% | 82 | 32.5% | 1285 | 35.8% |

| MI | 102 | 7.0% | 599 | 38.3% | 134 | 42.7% | 38 | 15.1% | 873 | 24.3% |

| Primary valve disease | 7 | 0.5% | 36 | 2.3% | 14 | 4.5% | 3 | 1.2% | 60 | 1.7% |

| Valve surgery | 8 | 0.5% | 57 | 3.6% | 13 | 4.1% | 6 | 2.4% | 84 | 2.3% |

| RV pacemaker | 17 | 1.2% | 147 | 9.4% | 19 | 6.1% | 11 | 4.4% | 194 | 5.4% |

| BV pacemaker | 0 | 0.0% | 65 | 4.2% | 6 | 1.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 71 | 2.0% |

| Resuscitation | 22 | 1.5% | 117 | 7.5% | 15 | 4.8% | 8 | 3.2% | 162 | 4.5% |

| PAOD | 56 | 3.8% | 137 | 8.8% | 31 | 9.9% | 25 | 10.0% | 249 | 6.9% |

| Cerebro‐vascular disease | 88 | 6.0% | 172 | 11.0% | 38 | 12.1% | 28 | 11.1% | 326 | 9.1% |

| COPD | 99 | 6.8% | 216 | 13.8% | 31 | 9.9% | 21 | 8.3% | 367 | 10.2% |

| Primary pulmonary hypertension | 3 | 0.2% | 23 | 1.5% | 3 | 1.0% | 3 | 1.2% | 32 | 0.9% |

| Depression | 140 | 9.6% | 136 | 8.7% | 12 | 3.8% | 35 | 13.9% | 323 | 9.0% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 33 | 2.3% | 404 | 25.9% | 71 | 22.8% | 35 | 13.9% | 543 | 15.2% |

| Anaemia | 91 | 6.5% | 411 | 27.0% | 77 | 26.0% | 45 | 18.6% | 624 | 18.1% |

| Laboratory | ||||||||||

| Haemoglobin (mmol/L) | 8.7 | .76 | 8.5 | 1.20 | 8.5 | 1.10 | 8.4 | 0.9 | 8.6 | 1.0 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140 | 2.45 | 140 | 3.85 | 140 | 3.84 | 140 | 3 | 140 | 3 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.32 | 0.53 | 4.32 | 0.51 | 4.44 | 0.57 | 4.20 | 0.49 | 4.32 | 0.53 |

| eGFR (Cock.‐Gold) | 59.3 | [59.8, 83.5] | 59.3 | [45.1, 79.5] | 59.1 | [47.8, 73.5] | 62.4 | [49.6, 75.4] | 65.0 | [51, 81] |

| NT‐proBNP | 91 | [49, 175] | 2369 | [885, 6108] | 832 | [402, 1963] | 296 | [181, 616] | 321 | [96, 1729] |

| ECG | ||||||||||

| Rhythm—Sinus | 1409 | 96.6% | 1027 | 65.8% | 226 | 72.4% | 206 | 82.1% | 2868 | 80.1% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 32 | 2.2% | 389 | 24.9% | 66 | 21.2% | 35 | 13.9% | 522 | 14.6% |

| Pacemaker | 14 | 1.0% | 133 | 8.6% | 20 | 6.4% | 8 | 3.2% | 175 | 5.1% |

| Other | 4 | 0.3% | 11 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.8% | 17 | 0.5% |

| Heart rate (ECG) | 67 | 11 | 79 | 18 | 74 | 16 | 67 | 13 | 72 | 16 |

| QT time | 392 | 32 | 394 | 57 | 398 | 48 | 409 | 37 | 395 | 46 |

| LBBB | 23 | 1.6% | 478 | 31.1% | 48 | 15.5% | 12 | 4.8% | 561 | 15.8% |

| RBBB | 72 | 4.9% | 139 | 9.0% | 21 | 6.8% | 28 | 11.2% | 260 | 7.3% |

| AV‐block | 173 | 11.9% | 164 | 11.1% | 31 | 10.4% | 32 | 13.1% | 400 | 11.5% |

| Echocardiography | ||||||||||

| LVEF | 61.2 | 6.3 | 29.1 | 7.0 | 42.4 | 2.6 | 60.1 | 7.4 | 45.5 | 16.6 |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; BV pacemaker, biventricular pacemaker; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECG, electrocardiogram; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid‐range ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HR, hazard ratio; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusive disease; RBBB, right bundle branch block; RV pacemaker, right ventricular pacemaker; SD, standard deviation.

All tests were performed two‐tailed at significance level α = 1%. The analyses were carried out by means of IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25 and the free statistical software R, version 3.6 including the package survival.

3. Results

3.1. Subject population

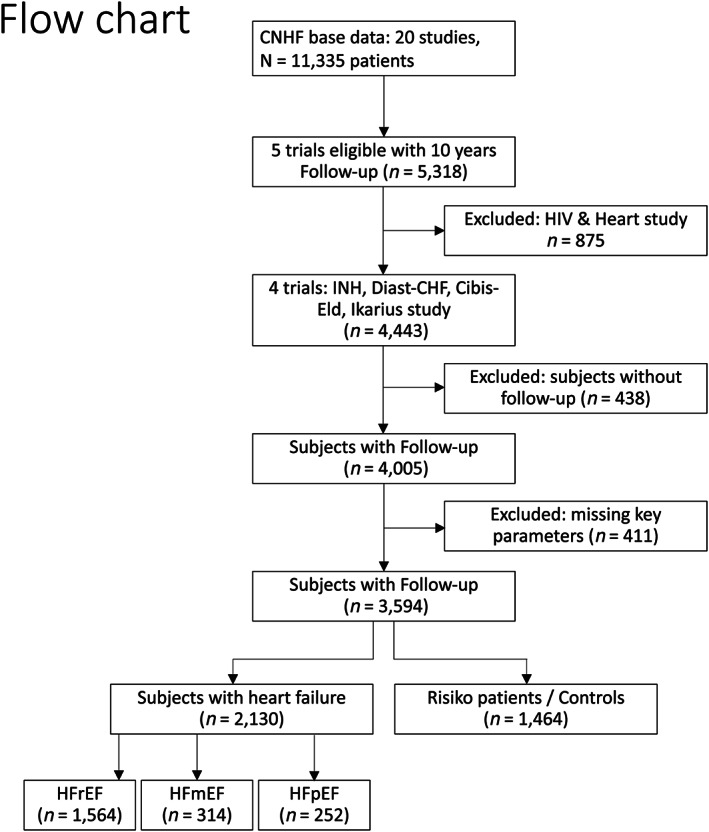

A total of 11 335 subjects were screened for analysis from the database; 3594 subjects were eligible and provided sufficient data for analysis (Figure 1 ). Of them, 1564 patients were with HFrEF (43.5%), 314 (8.7%) with HFmrEF, and 252 with HFpEF (7.0%), and 1464 were subjects without HF (40.7%). We considered the subjects without HF as controls in our study. Baseline characteristics of the different HF entities as well as the controls are described in Table 1. Table 2 describes the characteristics of the cohort with HoS versus the cohort without HoS.

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart (patients from the pooled databases). CNHF, Competence Network for Heart Failure; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction. *Not all studies provided the same inclusion and exclusion criteria; if basic data were missing according to our protocol, they were excluded (see Appendix A).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the population analysed based on the presence of HoS

| No HoS | HoS | Total | Cohen's d | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3070 | n = 524 | N = 3594 | OR | ||||

| General | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Probability of superiority |

| or | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| or | Median | [Quartiles] | Median | [Quartiles] | Median | [Quartiles] | |

| Age | 66.5 | 11.0 | 68.1 | 10.9 | 66.7 | 11.0 | 0.15 |

| Female sex | 1208 | 39.3% | 226 | 43.1% | 1434 | 39.9% | 0.86 |

| BMI | 28.0 | 4.8 | 27.7 | 4.8 | 27.9 | 4.8 | −0.05 |

| HR (at rest,) | 72 | 12 | 71 | 13 | 72 | 12 | −0.12 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 136 | 24 | 134 | 25 | 135 | 24 | −0.09 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 79.1 | 12.3 | 77.1 | 13.3 | 78.8 | 12.5 | −0.16 |

| NYHA I | 110 | 6.1% | 16 | 4.7% | 126 | 5.9% | — |

| NYHA II | 990 | 55.2% | 165 | 49.0% | 1155 | 54.3% | |

| NYHA III | 645 | 36.0% | 146 | 43.3% | 791 | 37.2% | |

| NYHA IV | 47 | 2.6% | 10 | 3.0% | 57 | 2.7% | |

| Medical history | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 829 | 27.0% | 133 | 25.4% | 962 | 26.8% | 1.09 |

| Hypertension | 2303 | 75.0% | 410 | 78.2% | 2713 | 75.5% | 0.83 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1491 | 48.6% | 299 | 57.1% | 1790 | 49.8% | 0.71 |

| Hyperuricaemia | 752 | 24.5% | 174 | 33.2% | 926 | 25.8% | 0.65 |

| Family history of MI | 426 | 13.9% | 101 | 19.3% | 527 | 14.7% | 0.67 |

| Smoking—No | 1471 | 48.1% | 270 | 51.6% | 1741 | 48.6% | — |

| Ex‐smoker | 403 | 13.2% | 55 | 10.5% | 458 | 12.8% | |

| Smoker | 1186 | 38.8% | 198 | 37.9% | 1384 | 38.6% | |

| CAD | 1084 | 35.3% | 201 | 38.4% | 1285 | 35.8% | 0.88 |

| MI | 744 | 24.2% | 129 | 24.6% | 873 | 24.3% | 0.98 |

| Primary valve disease | 49 | 1.6% | 11 | 2.1% | 60 | 1.7% | 0.76 |

| Valve surgery | 67 | 2.2% | 17 | 3.2% | 84 | 2.3% | 0.67 |

| RV pacemaker | 134 | 4.4% | 60 | 11.5% | 194 | 5.4% | 0.35 |

| BV pacemaker | 48 | 1.6% | 23 | 4.4% | 71 | 2.0% | 0.35 |

| Resuscitation | 96 | 3.1% | 66 | 12.6% | 162 | 4.5% | 0.22 |

| PAOD | 200 | 6.5% | 49 | 9.4% | 249 | 6.9% | 0.68 |

| Cerebro‐vascular disease | 255 | 8.3% | 71 | 13.5% | 326 | 9.1% | 0.58 |

| COPD | 295 | 9.6% | 72 | 13.7% | 367 | 10.2% | 0.67 |

| Primary pulmonary hypertension | 20 | 0.7% | 12 | 2.3% | 32 | 0.9% | 0.28 |

| Depression | 242 | 7.9% | 81 | 15.5% | 323 | 9.0% | 0.47 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 464 | 15.2% | 79 | 15.2% | 543 | 15.2% | 1.00 |

| Anaemia | 529 | 18.0% | 95 | 18.6% | 624 | 18.1% | 0.94 |

| Laboratory | |||||||

| Haemoglobin (mmol/L) | 8.58 | 1.03 | 8.52 | 0.99 | 8.58 | 1.02 | −0.06 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140.1 | 3.3 | 139.5 | 3.4 | 140.0 | 3.4 | −0.17 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.34 | 0.52 | 4.25 | 0.53 | 4.32 | 0.53 | −0.17 |

| eGFR (Cock.‐Gold, ml/min/1.73 m²) | 66 [52. 81] | 63 [47. 77] | 65 [51. 81] | 0.45 | |||

| NT‐proBNP | 316 [92.5. 1651] | 339 [125. 2027] | 321 [96. 1729 | 0.53 | |||

| ECG | |||||||

| Rhythm—Sinus | 2475 | 80.9% | 393 | 75.4% | 2868 | 80.1% | — |

| Atrial fibrillation | 449 | 14.7% | 73 | 14.0% | 522 | 14.6% | |

| Pacemaker | 28 | 0.9% | 13 | 2.5% | 41 | 1.1% | |

| Other | 13 | 0.4% | 4 | 0.8% | 17 | 0.5% | |

| Heart rate (ECG, bpm) | 73 | 16 | 72 | 16 | 72 | 16 | −0.07 |

| QT time | 394 | 45 | 402 | 49 | 395 | 46 | 0.18 |

| LBBB | 460 | 15.1% | 101 | 19.6% | 561 | 15.8% | 0.74 |

| RBBB | 211 | 6.9% | 49 | 9.5% | 260 | 7.3% | 0.72 |

| Echocardiography | |||||||

| LVEF | 45.5 | 16.5 | 45.8 | 17.4 | 45.5 | 16.6 | 0.02 |

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; BV pacemaker, biventricular pacemaker; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECG, electrocardiogram; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid‐range ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HoS, history of syncope; HR, hazard ratio; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; PAOD, peripheral arterial occlusive disease; RBBB, right bundle branch block; RV pacemaker, right ventricular pacemaker; SD, standard deviation.

3.2. Prevalence of history of syncope

Of all the subjects, 14.6% (524/3594) reported HoS (Table 2). Patients with HFrEF in our pooled cohort showed more often syncopes than subjects without HF (15.0% vs. 12.8%, P = 0.082) and more than with patients with HFmrEF (15.0% vs. 12.7%, P = 0.31) but distinctly less than with patients with HFpEF (15.0% vs. 25.0%, P < 0.001). HoS was most prevalent among patients with HFpEF.

3.3. Overall and hospitalization‐free survival

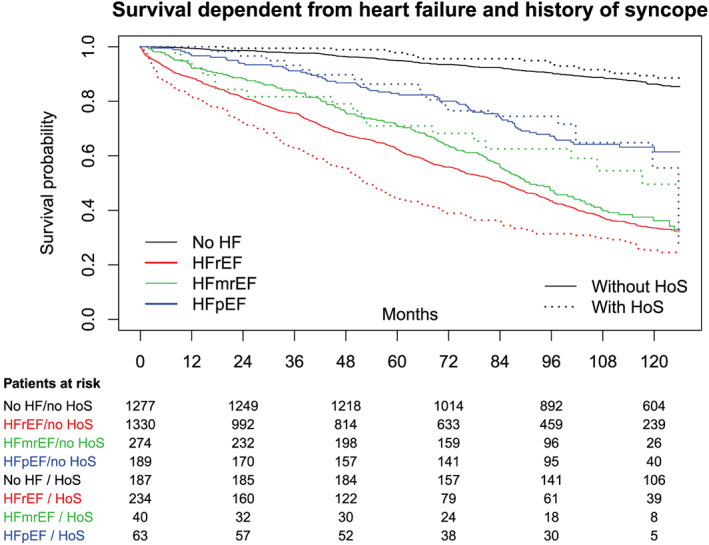

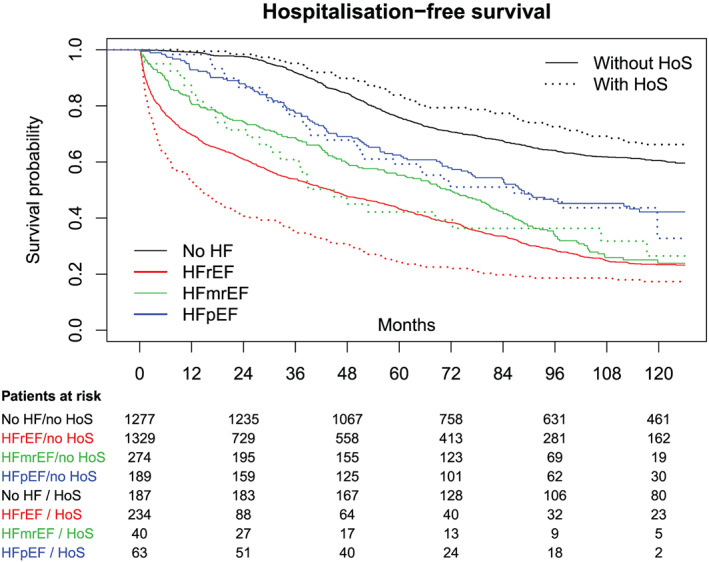

Among all subjects, those with HoS showed a worse 126 month survival [57.6% vs. 62.1%, HR = 1.17, 99% confidence interval (0.96, 1.41), P = 0.038] (Figure 2 ) and a worse hospitalization‐free survival up to 126 months follow‐up [43.1% vs. 45.5%, HR = 1.15, 99% confidence interval (0.98, 1.35), P = 0.03]. However, both are not significant at the 1% level.

Figure 2.

Ten year overall survival in the HF and control cohorts. HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, HF with mid‐range ejection fraction; HFpEF, HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction; HoS, history of syncope.

Among all patients with HFrEF, those with HoS showed a worse overall survival than those without HoS [30.3% vs. 41.6%, HR = 1.40, 99% confidence interval (1.12, 1.74), P < 0.001; Figure 2 ]. Also, hospitalization‐free survival was altered in the same manner in this cohort [with HoS: 21.8%, without HoS: 31.2%, HR = 1.49, 99% confidence interval (1.21, 1.83); Figure 3 ].

Figure 3.

Hospitalization‐free survival within a 10 year follow‐up in all cohorts. HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, HF with mid‐range ejection fraction; HFpEF, HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, HF with reduced ejection fraction; HoS, history of syncope.

Exploring the data of patients with HFmrEF and HFpEF resulted in no significant difference in overall or hospitalization‐free survival between patients with HoS and patients without HoS (HFmrEF: P = 0.85; HFpEF: P = 0.48).

3.4. Assessment of added single value to syncopes

We analysed the characteristics and risk factors associated with the endpoints in patients with HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF as well as in patients without HF separately (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors associated with mortality and hospital‐free survival.

| Hazard ratio | 99% confidence interval | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Risk factors multiply associated with all‐cause mortality | ||||

| Female sex | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.95 | 0.001 |

| Age (decades) | 1.74 | 1.57 | 1.92 | <0.001 |

| Smoking status (ref. non‐smoker) | ||||

| Ex‐smoker | 1.15 | 0.97 | 1.37 | 0.033 |

| Smoker | 1.59 | 1.20 | 2.09 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.28 | 1.09 | 1.50 | <0.001 |

| Anaemia | 1.27 | 1.07 | 1.52 | <0.001 |

| log10(NT‐proBNP) | 2.10 | 1.83 | 2.42 | <0.001 |

| CHD | 1.40 | 1.18 | 1.65 | <0.001 |

| Defibrillator | 1.53 | 1.10 | 2.12 | 0.001 |

| Primary valve disease | 1.43 | 0.94 | 2.17 | 0.030 |

| NYHA class (ref. no HF or NYHA I) | ||||

| II | 1.97 | 1.51 | 2.56 | <0.001 |

| III | 2.33 | 1.74 | 3.12 | <0.001 |

| IV | 3.86 | 2.36 | 6.32 | <0.001 |

| Medication | ||||

| Beta‐blockers | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| Diuretics | 1.32 | 1.06 | 1.65 | 0.001 |

| Model 2: Risk factors multiply associated with all‐cause mortality and hospitalization (first of both) | ||||

| Female sex | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 0.007 |

| Age (decades) | 1.48 | 1.37 | 1.60 | <0.001 |

| Smoking status (ref. non‐smoker) | ||||

| Ex‐smoker | 1.08 | 0.94 | 1.25 | 0.158 |

| Smoker | 1.32 | 1.05 | 1.65 | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.25 | 1.09 | 1.43 | <0.001 |

| CHD | 1.23 | 1.02 | 1.48 | 0.005 |

| History of MI | 1.26 | 1.04 | 1.52 | 0.002 |

| NYHA class (ref. no HF or NYHA I) | ||||

| II | 1.56 | 1.29 | 1.91 | <0.001 |

| III | 1.98 | 1.57 | 2.48 | <0.001 |

| IV | 3.31 | 2.11 | 5.20 | <0.001 |

| log10(NT‐proBNP) | 1.61 | 1.43 | 1.82 | <0.001 |

| Primary valve disease | 1.33 | 0.89 | 2.00 | 0.066 |

| Defibrillator | 1.38 | 1.02 | 1.88 | 0.006 |

| Anaemia | 1.28 | 1.09 | 1.50 | <0.001 |

| Medication with beta‐blockers | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.93 | <0.001 |

CHD, coronary heart disease; HF, heart failure; NT‐proBNP, N terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

In particular, age [HR = 1.48, 99% confidence interval (1.37, 1.60), P < 0.001] and clinical severity of HF, measured both in higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) class [for NYHA II: HR = 1.56, 99% confidence interval (1.29, 1.91), P < 0.001; for NYHA III: HR = 1.98, 99% confidence interval (1.57, 2.48), P < 0.001; for NYHA IV: HR = 3.31, 99% confidence interval (2.11, 5.20), P < 0.001] and in higher NT‐proBNP levels [for log10(NT‐proBNP) HR = 1.61, 99% confidence interval (1.43, 1.82), P < 0.001], were strong predictors of a reduced overall and hospitalization‐free survival. Male sex, age, smoking (both smokers and ex‐smokers), diabetes, coronary artery disease, and anaemia were also associated with reaching early one of the endpoints. Taking these factors into account, HoS showed no added information on the endpoints, that is, the effect of HoS is completely explained by the other factors.

4. Discussion

In this analysis, we show that syncopes represent clinically a high‐risk profile among patients with HFrEF. Our data indicate the increased prevalence of HoS in patients with HF and a strong association of syncopes in patients with HFrEF with reduced overall and hospitalization‐free survival compared with patients with HFmrEF and HFpEF as well as controls without HF within a 10 year follow‐up. Our analysis is the first to focus on syncopes in a large HF population, including only pooled prospective data.

This is a highly relevant finding as risk assessment remains a main goal within HF diagnostics and therapy and the assessment of HoS adds significantly to an easily accessible characterization of this HF population.

While due to the study designs the causes for syncope were not recorded, the presence of HoS provides relevant information. Our multiple model calculations showed that the value of HoS as a predictive parameter is explained by the risk profile that patients with HFrEF with HoS suffer from, including co‐morbidities. They suffer from these risk factors more often and in a higher degree than patients with HFrEF without HoS, that is, patients with HFrEF with HoS are sicker than those without HoS. This highlights that HoS represents a clinically and easily accessible insight into a prognostic pattern for both the overall survival and the time to the first hospitalization.

History of syncope is like a multi‐parameter risk score providing not a number at high risk but a clinical symptom.

Exploring the outcome differences between the HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF groups, further investigation of the underlying pathophysiology of the syncopes is required, so we challenged our results with different interpretations.

With stroke volume being impaired in both HFrEF and HFpEF, reduced cardiac output is unlikely to describe the mechanism of action.

Regarding an arrhythmogenic genesis and potential sudden cardiac death, much has been debated about the significance of LVEF per se as a prognostic value, especially because the association of low LVEF with fatal arrhythmia or death from worsening HF is not proportional and controversial.2, 18 Recent trials showed the heterogeneous benefit from implantable cardioverter–defibrillator (ICD) therapy within the HFrEF population, for example, no benefit in non‐ischaemic cardiomyopathy, leaving the risk assessment in different cardiomyopathies to debate.18 Our analyses explain the increased risk not monocausal but in a holistic approach, which is a representative clinical symptom.

In our cohort, patients with HoS were more likely to suffer from arrhythmia clearly evident in more implanted cardiac devices (ICD, right ventricular, and LV pacemakers) as well as history of resuscitation. Ruwald et al.19 showed in patients with HFrEF with implanted ICDs that syncopes are, irrespective of the cause, indicators for increased mortality, and we could confirm this finding.

Autonomic dysfunction (AD) plays a major role in both sudden cardiac death and syncopes as well as in HF.20 In addition, HF is also associated with chronotropic incompetence (CI).21 CI leads to the limitation of physical activity and amplifies the HF symptoms. Unfortunately, we have only ECG results and have no access to the ECG raw data, holter ECG recordings, or cardiac stress tests, which constrains us in evaluating the influence of AD and CI on our results.

Casiglia et al.22 showed that orthostatic hypotension (OH) correlates with cardiovascular co‐morbidities and provides a morbidity burden but without any impact on survival data. Because we do not have data from tilt testing or other diagnostic tools for OH, we cannot measure the value of OH, but we consider the impact of OH on our data very low because both hospital‐free and overall survival are affected in patients with HoS.

Moreover, because HF is characterized by upregulation of the sympathetic nervous system and abnormal responsiveness of the parasympathetic nervous system and that influences also AD as well as OH, we need to highlight an increase in cardiac adrenergic drive as a potential origin of syncopes.23 Both chronotropy and inotropy are altered by the level of adrenergic drive and make the circulation susceptible for sudden changes and syncopes through limited response in heart rate and blood pressure. This system is altered not only by HF but also by medication. Particularly, beta‐blockers aim to reduce the sympathetic effect on the heart and are a recommended therapy for patients suffering from HFrEF. As a result, patients suffer from an iatrogenic chronotropic incompetence and reduced blood pressure, both relevant factors in the origin of syncopes.24 Furthermore, adrenergic receptors of the vasculature are key not only to cardiac syncopes but also to neurally mediated syncopes—not to differentiate in our cohort as we do not have any information on the origin.25, 26 In our cohort, blood pressure did not show a relevant association with the endpoints and was omitted from the risk model. Beta‐blockers showed an effect on the survival endpoint. We see this finding in the context of patients with HFrEF with HoS showing a worse outcome than patients with other HF entities, and beta‐blockers are more frequently taken among patients with HFrEF than among others. At the same time, these patients suffer probably more often by the side‐described side effects of beta‐blockers; beta‐blockers explain the syncopes only partially in our risk model.

Furthermore, HF medication per se, for example, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, also triggers syncopes as a side effect.27 A Danish register study revealed a substantial association between cardiovascular pharmacotherapy and syncopes.28 Likewise, the Danish study confirmed that the cardiovascular risk factors such as chronic kidney disease, anaemia, diabetes, and other co‐morbidities are associated not only with cardiovascular mortality but also with HoS, and we could show this in a prospective HF population.

4.1. Study limitations

However, as stated, the present study has several limitations. The limitations primarily involve the study population and the validity of the registered HoS. This analysis of pooled data by the German CNHF, like any other study, deals with the possibility of unmeasured confounding biases while providing access to a large number of patients. In particular, considering the total network population, although studies were harmonized within the framework, they still were different, including different inclusion and exclusion criteria, biomarker assay methods, and reported parameters. All subjects were seen at sites conducting studies of the German CNHF; therefore, the study population despite its size is not equivalent to real‐world data. These effects are set against a long follow‐up and a high quality of the endpoint data because they were registered in studies and were not from registries. Regarding the validity of HoS, the major limitation refers to the fact that the syncopes were not categorized based on pathophysiological causes in the databases. Hence, we do not have data on further aetiological work‐up of these syncopes.

5. Conclusions

We show for the first time that syncopes represent a high‐risk profile and poorer overall and hospital‐free survival in a large HF cohort from several prospective studies, resulting in a higher mortality and a shorter hospital‐free survival especially in the HFrEF cohort compared with the HFmrEF group, the HFpEF group, or the controls without HF.

This is highly relevant because this finding offers a better and easily accessible characterization of the HF cohort; HoS may change diagnostic and therapeutic decisions regarding closer follow‐ups and further risk assessment.

The pathophysiology of HoS remains undefined, while it is a valuable predictor for overall and hospitalization‐free survival in patients with HF. Noting this should include HoS in the standard evaluation of every patient. HoS shows a high‐risk profile for mortality and hospitalization in the HFrEF cohort.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Competence Network for Heart Failure, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude towards all participating patients and subjects, the colleagues involved in the German Competence Network for HF, and the involved personnel who supported the clinical studies. We would especially like to acknowledge the contribution of Tobias Daniel Trippel, who supported and guided this analysis substantially throughout all phases.

APPENDIX A.

Inclusion criteria:

Completed basic clinical dataset

Exclusion criteria:

No echocardiography details on left ventricle ejection fraction or E/e′

Aortic valve stenosis

No laboratory details on serum electrolytes, haemoglobin or creatinine

No details on blood pressure

No details on co‐morbidities

No details on implanted implantable cardioverter–defibrillator or pacemaker devices

No electrocardiogram details

Previous resuscitation

Regular alcohol consumption

Hashemi, D. , Blum, M. , Mende, M. , Störk, S. , Angermann, C. E. , Pankuweit, S. , Tahirovic, E. , Wachter, R. , Pieske, B. , Edelmann, F. , Düngen, H.‐D. , and the German Competence Network for Heart Failure (2020) Syncopes and clinical outcome in heart failure: results from prospective clinical study data in Germany. ESC Heart Failure, 7: 942–952. 10.1002/ehf2.12605.

References

- 1. Brignole M, Moya A, de Lange FJ, Deharo J‐C, Elliott PM, Fanciulli A, Fedorowski A, Furlan R, Kenny RA, Martín A, Probst V, Reed MJ, Rice CP, Sutton R, Ungar A, van Dijk JG, Torbicki A, Moreno J, Aboyans V, Agewall S, Asteggiano R, Blanc J‐J, Bornstein N, Boveda S, Bueno H, Burri H, Coca A, Collet J‐P, Costantino G, Díaz‐Infante E, ESC Scientific Document Group . ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope. Eur Heart J 2018; 2018: 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola V‐P, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P, Authors/Task Force Members, Document Reviewers . 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, Blanc JJ, Brignole M, Dahm JB, Deharo JC, Gajek J, Gjesdal K, Krahn A, Massin M, Pepi M, Pezawas T, Granell RR, Sarasin F, Ungar A, VanDijk JG, Walma EP, Wieling W, Abe H, Benditt DG, Decker WW, Grubb BP, Kaufmann H, Morillo C, Olshansky B, Parry SW, Sheldon R, Shen WK, Vahanian A, Auricchio A, Bax J, Ceconi C, Dean V, Filippatos G, Funck‐Brentano C, Hobbs R, Kearney P, McDonagh T, McGregor K, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Vardas P, Widimsky P, Auricchio A, Acarturk E, Andreotti F, Asteggiano R, Bauersfeld U, Bellou A, Benetos A, Brandt J, Chung MK, Cortelli P, Da CA, Extramiana F, Ferro J, Gorenek B, Hedman A, Hirsch R, Kaliska G, Kenny RA, Kjeldsen KP, Lampert R, Molgard H, Paju R, Puodziukynas A, Raviele A, Roman P, Scherer M, Schondorf R, Sicari R, Vanbrabant P, Wolpert C, Zamorano JL. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 2631–2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bleumink GS, Knetsch AM, Sturkenboom MCJM, Straus SMJM, Hofman A, Deckers JW, Witteman JCM, Stricker BHC. Quantifying the heart failure epidemic: prevalence, incidence rate, lifetime risk and prognosis of heart failure The Rotterdam Study. Eur Heart J 2004; 25: 1614–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Soteriades ES, Evans JC, Larson MG, Chen MH, Chen L, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Incidence and prognosis of syncope. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 878–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vaduganathan M, Patel RB, Michel A, Shah SJ, Senni M, Gheorghiade M, Butler J. Mode of death in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol Elsevier 2017; 69: 556–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola V‐P, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 891–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olshansky B, Poole JE, Johnson G, Anderson J, Hellkamp AS, Packer D, Mark DB, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Syncope predicts the outcome of cardiomyopathy patients. Analysis of the SCD‐HeFT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 1277–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Middlekauff HR, Stevenson WG, Stevenson LW, Saxon LA. Syncope in advanced heart failure: high risk of sudden death regardless of origin of syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol; Elsevier Masson SAS 1993; 21: 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. El‐Menyar A, Sulaiman K, AlSadawi A, AlSheikh‐Ali A, AlMahameed W, Bazargani N, AlMotarreb A, Amin H, Asaad N, Al HK, Ridha M, Al‐Jarallah M, Al‐Thani H, Al‐Faleh H, Singh R, Panduranga P, Al SJ. Implications of a history of syncope in patients hospitalized with heart failure: insights from the Gulf CARE registry. Angiology 2017; 68: 196–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lund LH, Donal E, Oger E, Hage C, Persson H, Haugen‐Lofman I, Ennezat PV, Sportouch‐Dukhan C, Drouet E, Daubert JC, Linde C. Association between cardiovascular vs. non‐cardiovascular co‐morbidities and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2014; 16: 992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mehrhof F, Löffler M, Gelbrich G, Özcelik C, Posch M, Hense HW, Keil U, Scheffold T, Schunkert H, Angermann C, Ertl G, Jahns R, Pieske B, Wachter R, Edelmann F, Wollert KC, Maisch B, Pankuweit S, Erbel R, Neumann T, Herzog W, Katus H, Müller‐Tasch T, Zugck C, Düngen HD, Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Störk S, Siebert U, Wasem J, Neumann A, Göhler A, Anker SD, Köhler F, Möckel M, Osterziel KJ, Dietz R, Rauchhaus M, Competence Network Heart Failure . A network against failing hearts—introducing the German ‘Competence Network Heart Failure'. Int J Cardiol 2010; 145: 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morbach C, Marx A, Kaspar M, Güder G, Brenner S, Feldmann C, Störk S, Vollert JO, Ertl G, Angermann CE. Prognostic potential of midregional pro‐adrenomedullin following decompensation for systolic heart failure: comparison with cardiac natriuretic peptides. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 19: 1166–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Angermann CE, Störk S, Gelbrich G, Faller H, Jahns R, Frantz S, Loeffler M, Ertl G. Mode of action and effects of standardized collaborative disease management on mortality and mobidity in patient with systolic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2012; 5: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Düngen HD, Apostolović S, Inkrot S, Tahirović E, Töpper A, Mehrhof F, Prettin C, Putniković B, Neškovi AN, Krotin M, Sakać D, Lainščak M, Edelmann F, Wachter R, Rau T, Eschenhagen T, Doehner W, Anker SD, Waagstein F, Herrmann‐Lingen C, Gelbrich G, Dietz R. Titration to target dose of bisoprolol vs. carvedilol in elderly patients with heart failure: the CIBIS‐ELD trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13: 670–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Edelmann F, Stahrenberg R, Polzin F, Kockskämper A, Düngen HD, Duvinage A, Binder L, Kunde J, Scherer M, Gelbrich G, Hasenfuß G, Pieske B, Wachter R, Herrmann‐Lingen C. Impaired physical quality of life in patients with diastolic dysfunction associates more strongly with neurohumoral activation than with echocardiographic parameters: quality of life in diastolic dysfunction. Am Heart J Mosby, Inc 2011; 161: 797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Køber L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, Haarbo J, Videbæk L, Korup E, Jensen G, Hildebrandt P, Steffensen FH, Bruun NE, Eiskjær H, Brandes A, Thøgersen AM, Gustafsson F, Egstrup K, Videbæk R, Hassager C, Svendsen JH, Høfsten DE, Torp‐Pedersen C, Pehrson S, DANISH Investigators . Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1221–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ruwald MH, Okumura K, Kimura T, Aonuma K, Shoda M, Kutyifa V, Ruwald A‐CH, McNitt S, Zareba W, Moss AJ. Syncope in high‐risk cardiomyopathy patients with implantable defibrillators: frequency, risk factors, mechanisms, and association with mortality: results from the multicenter automatic defibrillator implantation trial‐reduce inappropriate therapy (MADIT). Circulation 2014; 129: 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tjeerdsma G, Szabó BM, van Wijk LM, Brouwer J, Tio RA, Crijns HJ, van Veldhuisen DJ. Autonomic dysfunction in patients with mild heart failure and coronary artery disease and the effects of add‐on beta‐blockade. Eur J Heart Fail 2001; 3: 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shen H, Zhao J, Zhou X, Li J, Wan Q, Huang J, Li H, Wu L, Yang S, Wang P. Impaired chronotropic response to physical activities in heart failure patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2017; 17: 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Casiglia E, Tikhonoff V, Caffi S, Boschetti G, Giordano N, Guidotti F, Segato F, Mazza A, Grasselli C, Saugo M, Rigoni G, Guglielmi F, Martini B, Palatini P. Orthostatic hypotension does not increase cardiovascular risk in the elderly at a population level. Am J Hypertens 2014; 27: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol Elsevier Inc 2009; 54: 1747–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boh‐Oka SI, Ohmori H, Kawabe T, Tutiyama Y, Shimamoto Y, Shioji SS, Obana M, Satani O, Wanaka Y, Hamada M, Baba A, Tsuda K, Hano T, Nishio I. Neurally mediated syncope and cardiac β‐adrenergic receptor function. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 2001; 38: S75–S79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ono T, Saitoh H, Atarashi H, Hayakawa H. Abnormality of α‐adrenergic vascular response in patients with neurally mediated syncope. Am J Cardiol 1998; 82: 438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saito F, Imai S, Tanaka N, Tanaka H, Suzuki K, Takase H, Aoyama H, Matsudaira K, Ebuchi T, Akamine Y, Takahashi N, Sugino K, Kanmatsuse K, Yagi H, Kushiro T. Basic autonomic nervous function in patients with neurocardiogenic syncope. Clin Exp Hypertens 2007; 29: 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kostis JB, Shelton B, Gosselin G, Goulet C, Hood WB, Kohn RM, Kubo SH, Schron E, Weiss MB, Willis PW, Young JB, Probstfield J. Adverse effects of enalapril in the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). SOLVD Investigators. Am Heart J 1996; 131: 350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ruwald MH, Hansen ML, Lamberts M, Hansen CM, Højgaard MV, Køber L, Torp‐Pedersen C, Hansen J, Gislason GH. The relation between age, sex, comorbidity, and pharmacotherapy and the risk of syncope: a Danish nationwide study. Europace 2012; 14: 1506–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]