Abstract

Objectives.

Evaluate the prevalence of meeting the updated 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (150 unbouted minutes in moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity [MVPA]) and determine cross-sectional factors associated with Guideline attainment in a community-based cohort of adults with or at elevated risk for knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Methods.

Physical activity was monitored for one week in a subset of Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) participants with or at increased risk for knee OA. Accelerometer-measured weekly MVPA minutes were calculated; sociodemographic (age, sex, race, education, and working status) and health-related (BMI, comorbidity, depressive symptoms, radiographic knee OA, and frequent knee symptoms) factors were assessed. We evaluated the prevalence of meeting 2018 Guidelines and used multivariate partial proportional odds model to identify factors associated with Guideline attainment, controlling for other factors in the model.

Results.

Among 1922 participants (age 65.1 [SD 9.1] years, BMI 28.4 [4.8] kg/m2, 55.2% women), 44.1% men and 22.2% women met the 2018 PA Guidelines. Adjusted cross-sectional factors associated with not-meeting 2018 Guidelines were: women, older age, higher BMI, non-Whites, depressive symptoms, not working, and frequent knee symptoms.

Conclusion.

In community-recruited adults with or at high risk for knee OA, more than 50% of men and nearly 80% of women failed to achieve the 2018 recommended level of at least 150 weekly unbouted minutes of MVPA. Study findings support gender and racial disparity in Guideline attainment and suggest addressing potentially modifiable factors (e.g., BMI, depressive symptoms, and frequent knee symptoms) to optimize benefits in PA-promoting interventions.

Keywords: Physical activity, Guidelines, Osteoarthritis, Knee

INTRODUCTON

Among Americans 45 years and older, 43% have frequent knee pain, aching or stiffness, primarily due to knee osteoarthritis (OA).1 Knee OA is responsible for as much chronic disability as cardiovascular disease2 and has been linked to increased risk of all-cause mortality;3 its impact is likely to increase with the aging population, obesity epidemic, and paucity of disease-modifying treatment. Physical activity (PA) and exercise therapy are recommended as the first-line intervention and self-management of knee OA.4 PA is particularly beneficial for this population, given that many adults with knee OA also have comorbidities that may benefit from regular PA, such as cardiovascular disease,5 diabetes,6 and hypertension.7

Unlike the prior 2008 PA recommendation, the newly published 2018 PA Guidelines for Americans8 by the Department of Health and Human Services no longer require PA to occur in bouts of at least 10 minutes to count as ‘healthful’. Current evidence confirmed any amount of moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA (MVPA) contributes to health benefits, independent of the amount of bouted MVPA.9,10 Knee pain and/or fear of aggravating symptoms and joint damage are commonly identified barriers to achieving the recommend PA participation in the setting of knee OA.11,12 The updated 2018 PA Guidelines that give credit to every minute of MVPA is a welcoming modification because older adults with chronic knee complaints may find it challenging to accrue sustained MVPA ≥ 10 minutes needed to meet the prior recommendation of 150-min bouted MVPA per week. We recently reported, in individuals with lower extremity joint symptoms, attaining approximately 60-min MVPA per week (no bout constraint) significantly increased the likelihood of maintaining disability-free status over 4 years.13 This benchmark serves as an achievable intermediate step toward meeting the updated PA Guidelines and motivates those with chronic knee pain and/or functional limitations to engage in PA.

It is widely recognized that men and women differ in their PA levels;14–16 approaches that address this gender gap could potentially have a significant health impact.17 Proportion of men and women with or at elevated risk for knee OA meeting the updated PA Guidelines (i.e.,150-min weekly unbouted MVPA) and the disability-free threshold (i.e., 60-min weekly unbouted MVPA) have not been documented. Cross-sectional factors associated with meeting each threshold have not been examined. We sought to (1) evaluate the prevalence of attaining ≥ 150 vs. 60–149 vs. < 60 weekly minutes of unbouted MVPA; and (2) determine cross-sectional factors associated with Guideline attainment, in a community-based cohort of adults with or at elevated risk for knee OA.

METHODS

Study Sample.

The Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) is a prospective observational cohort study of 4796 men and women aged 45–79 years at enrollment, all with or at increased risk of developing symptomatic, radiographic knee OA. Annual OAI evaluations began in 2004 at four clinical sites: Baltimore MD, Columbus OH, Pittsburgh PA, and Pawtucket RI. The OAI recruited progression and incidence sub-cohorts.18 Progression sub-cohort participants were required to have symptomatic, radiographic knee OA, defined as the presence of both of the following in at least one knee at baseline: pain, aching or stiffness in or around the knee on most days for at least 1 month during the past 12 months; and a definite tibiofemoral osteophyte. Incidence sub-cohort participants did not have symptomatic, radiographic knee OA in either knee at baseline but had characteristics that placed them at increased risk of developing it during the study. The age-specific criteria for established risk factors included knee symptoms in a native knee in the past 12 months; being overweight, defined according to sex- and age-specific cutpoints for weight; knee injury causing difficulty walking for at least a week; history of any knee surgery; family history of a total knee replacement for OA in a biological parent or sibling; Heberden’s nodes; repetitive knee bending at work or outside of work; and aged 70–79 years. Exclusion criteria18 were rheumatoid or inflammatory arthritis; severe bilateral joint space narrowing; unilateral total knee replacement and severe contralateral joint space narrowing; bilateral total knee replacement or plan for it in the next 3 years; contraindications to MRI or inability to fit in the scanner or in the knee coil (i.e., men over 285 lbs and women over 250 lbs); positive pregnancy test; inability to provide a blood sample; use of walking aids other than a single straight cane for more than 50% of the time during ambulation; comorbid conditions precluding participation in a 4-year study; and current participation in a double-blind randomized trial.

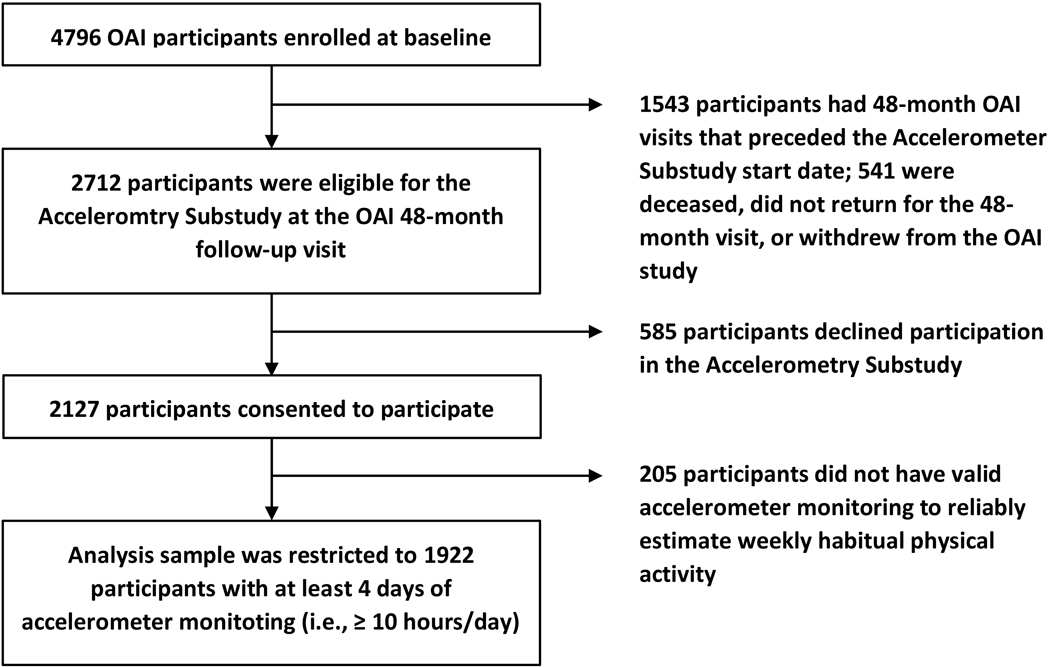

An accelerometry substudy was conducted at the 48-month OAI clinic visit in 2127 participants. Eligibility for the substudy required a scheduled OAI follow-up visit between August 2008 and July 2010, with staggered starting months across the OAI sites. The sample derivation is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Analysis sample derivation.

Accelerometer-measured PA at the 48-month OAI Clinic Visit.

Trained research personnel at each OAI site gave uniform scripted in-person instructions to wear the uniaxial accelerometer (ActiGraph GT1M, Pensacola, FL) for 7 consecutive days on a belt at the natural waistline on the right hip in line with the right axilla from arising in the morning until retiring, except during bath/shower and water activities. The reliability of accelerometry-based PA measures has been documented (ICC = 0.80 to 0.98).19–22 Accelerometer counts have strong relationships with energy expenditure,23–25 supporting its validity. Energy expenditure estimated by accelerometers vs. whole- room indirect calorimetry had correlations ranged from r = 0.82 during sedentary time to r = 0.96 during walking, with correlation for all activities at r = 0.95.25 Accelerometer nonwear periods were defined as intervals of ≥ 90 minutes with zero activity counts allowing for 2 consecutive interrupted minutes with counts below 100.26 For reliable estimates of weekly habitual PA, we restricted analyses to 1922 (90.4%) participants with at least 4 days of valid accelerometer monitoring (i.e., ≥ 10 hours/day).27 Daily unbouted (2018 Guidelines) minutes spent in MVPA were computed by using the cutpoint of ≥ 2020 activity counts/minute.26 Weekly MVPA minutes were summed for participants with 7 valid monitoring days or estimated as 7 times the average daily total for those with 4–6 valid monitoring days. To compare 2018 PA Guideline attainment with 2008 Guideline attainment, we also calculated each participant’s weekly bouted MVPA minutes (2008 Guidelines), using the same raw accelerometry data. Bouted MVPA minutes were defined as minutes consisting of ≥ 2020 activity counts/minute, accumulated in bouts of a minimum duration of 10 minutes.26

Assessment of Sociodemographic and Health-related Factors at the 48-month OAI Clinic Visit.

Sociodemographic and health-related variables were selected for analysis based on plausible rationale and/or previous literature concerning PA in persons with or at elevated risk for knee OA. Race was by self-report (White or Caucasian, Black or African American, Asian, and Other non-White); education by self-report (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, some graduate school, and graduate degree). BMI (kg/m2) was computed using measured body weight and height. Comorbidity was assessed by the adapted version of Charlson Comorbidity Index (range: 0–10);28 depressive symptoms by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (range: 0–60).29 Working status (yes vs. no) was assessed by questions on whether respondents currently do any paid or unpaid work, including self-employed work. Knee OA disease severity by Kellgren/Lawrence (K/L) grade (range: 0–4) was evaluated centrally by two experts, blinded to each other’s reading and all other data. Radiographic knee OA was defined as ≥ K/L 2 in at least one knee; frequent knee symptoms defined as having pain, aching or stiffness for ≥ half of the days of a month (in the past year) in at least one knee.

Statistical Analysis.

Descriptive summary for three categories of weekly unbouted MVPA minutes (≥ 150 vs. 60–149 vs. < 60 minutes) were reported separately for men and women. To identify cross-sectional factors independently associated with attaining 150-min weekly MVPA (compared to < 150-min MVPA) and 60-min weekly MVPA (compared to < 60-min MVPA), we used multivariate partial proportional odds model. Examined factors included: sex (women vs. men), age (unit: 5 years), BMI (unit: kg/m2), race (White vs. non-White), education (college graduate or above vs. non-college graduate), comorbidity (score 1 and ≥ 2 vs. 0), depressive symptoms (CES-D score ≥ 16 vs. < 16), working status (yes vs. no), presence of radiographic knee OA (yes vs. no), and report of frequent knee symptoms (yes vs. no). We reported adjusted odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals separately for ≥ vs. < 150-min and ≥ vs. < 60-min weekly unbouted MVPA.

RESULTS

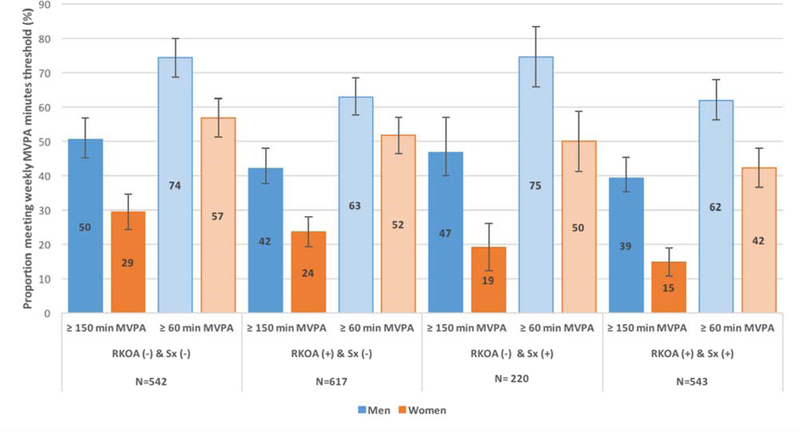

Table 1 shows sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of 1922 participants (mean age 65.1 [SD 9.1] years, BMI 28.4 [4.8] kg/m2, 55.2% women) in each of the three weekly unbouted MVPA minute categories (i.e., ≥ 150, 60–149, and < 60 minutes), presented separately for men and women. Specifically, 44.1% men and 22.2% women met the 2018 PA Guidelines. In contrast, applying the 2008 PA Guidelines (≥ 150-min weekly bouted MVPA) to the same raw accelerometry data, 17.2% men and 9.2% women met the 2008 Guidelines. Proportion of men and women attaining respective 150-min and 60-min weekly unbouted MVPA among (1) those without either radiographic knee OA or frequent knee symptoms, (2) those with radiographic knee OA but without frequent knee symptoms, (3) those with frequent knee symptoms but without radiographic knee OA, and (4) those with both radiographic knee OA and frequent knee symptoms, are plotted in Figure 2. As shown in Table 2, being a woman, older, non-White, and not working; and having higher BMI, depressive symptoms, and frequent knee symptoms were each associated with reduced odds of attaining the 2018 PA Guidelines (150-min weekly unbouted MVPA) (reference group: persons achieving < 150 minutes). Being a woman, older, and not working; and having higher BMI, any comorbidity, and depressive symptoms were each associated with reduced odds of attaining 60-minute threshold (reference group: persons achieving < 60 minutes).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by physical activity levels among men and women

| Characteristics | Weekly unbouted MVPA minutes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 60 min | 60–149 min | ≥ 150 min | ||

| Men | n | n (row %) | ||

| Overall | 861 | 283 (32.9%) | 198 (23.0%) | 380 (44.1%) |

| Age, years | ||||

| 49–59 | 315 | 43 (13.7%) | 83 (26.3%) | 189 (60.0%) |

| 60–69 | 264 | 79 (29.9%) | 56 (21.2%) | 129 (48.9%) |

| ≥ 70 | 282 | 161 (57.1%) | 59 (20.9%) | 62 (22.0%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 168 | 41 (24.4%) | 38 (22.6%) | 89 (53.0%) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 389 | 112 (28.8%) | 92 (23.7%) | 185 (47.6%) |

| Obese (≥ 30) | 304 | 130 (42.8%) | 68 (22.4%) | 106 (34.9%) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 763 | 251 (32.9%) | 169 (22.1%) | 343 (45.0%) |

| Non-White | 98 | 32 (32.7%) | 29 (29.6%) | 37 (37.8%) |

| Education | ||||

| College graduate or above | 779 | 242 (31.1%) | 182 (23.4%) | 355 (45.6%) |

| Non-college graduate | 82 | 41 (50.0%) | 16 (19.5%) | 25 (30.5%) |

| Comorbidity score | ||||

| 0 | 589 | 153 (26.0%) | 140 (23.8%) | 296 (50.3%) |

| 1 | 138 | 66 (47.8%) | 29 (21.0%) | 43 (31.2%) |

| ≥ 2 | 134 | 64 (47.8%) | 29 (21.6%) | 41 (30.6%) |

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||

| CES-D score < 16 | 776 | 248 (32.0%) | 174 (22.4%) | 354 (45.6%) |

| CES-D score ≥ 16 | 85 | 35 (41.2%) | 24 (28.2%) | 26 (30.6%) |

| Current Working Status | ||||

| Working | 521 | 113 (21.7%) | 131 (25.1%) | 277 (53.2%) |

| Not working | 340 | 170 (50.0%) | 67 (19.7%) | 103 (30.3%) |

| Radiographic Disease | ||||

| RKOA (−) | 340 | 87 (25.6%) | 85 (25.0%) | 168 (49.4%) |

| RKOA (+) | 521 | 196 (37.6%) | 113 (21.7%) | 212 (40.7%) |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Frequent knee symptoms (−) | 515 | 163 (31.7%) | 115 (22.3%) | 237 (46.0%) |

| Frequent knee symptoms (+) | 346 | 120 (34.7%) | 83 (24.0%) | 143 (41.3%) |

| Women | n | n (row %) | ||

| Overall | 1061 | 527 (49.7%) | 298 (28.1%) | 236 (22.2%) |

| Age, years | ||||

| 49–59 | 304 | 82 (27.0%) | 114 (37.5%) | 108 (35.5%) |

| 60–69 | 381 | 171 (44.9%) | 124 (32.5%) | 86 (22.6%) |

| ≥ 70 | 376 | 274 (72.9%) | 60 (16.0%) | 42 (11.2%) |

| BMI | ||||

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 320 | 124 (38.8%) | 93 (29.1%) | 103 (32.2%) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 367 | 189 (51.5%) | 99 (27.0%) | 79 (21.5%) |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 374 | 214 (57.2%) | 106 (28.3%) | 54 (14.4%) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 836 | 410 (49.0%) | 225 (26.9%) | 201 (24.0%) |

| Non-White | 225 | 117 (52.0%) | 73 (32.4%) | 35 (15.6%) |

| Education | ||||

| College graduate or above | 887 | 417 (47.0%) | 255 (28.7%) | 215 (24.2%) |

| Non-college graduate | 174 | 110 (63.2%) | 43 (24.7%) | 21 (12.1%) |

| Comorbidity score | ||||

| 0 | 762 | 344 (45.1%) | 230 (30.2%) | 188 (24.7%) |

| 1 | 192 | 110 (57.3%) | 43 (22.4%) | 39 (20.3%) |

| ≥ 2 | 107 | 73 (68.2%) | 25 (23.4%) | 9 (8.4%) |

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||

| CES-D score < 16 | 917 | 448 (48.9%) | 258 (28.1%) | 211 (23.0%) |

| CES-D score ≥ 16 | 144 | 79 (54.9%) | 40 (27.8%) | 25 (17.4%) |

| Current Working Status | ||||

| Working | 529 | 193 (36.5%) | 173 (32.7%) | 163 (30.8%) |

| Not working | 532 | 334 (62.8%) | 125 (23.5%) | 73 (13.7%) |

| Radiographic Disease | ||||

| Radiographic knee OA (−) | 422 | 191 (45.3%) | 120 (28.4%) | 111 (26.3%) |

| Radiographic knee OA (+) | 639 | 336 (52.6%) | 178 (27.9%) | 125 (19.6%) |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Frequent knee symptoms (−) | 644 | 296 (46.0%) | 179 (27.8%) | 169 (26.2%) |

| Frequent knee symptoms (+) | 417 | 231 (55.4%) | 119 (28.5%) | 67 (16.1%) |

MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity; BMI = body mass index; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale

Figure 2.

In OAI participants with or at elevated risk for knee OA (n=1922), proportion of men and women meeting respective unbouted 150-min and 60-min weekly MVPA among 4 mutually exclusive groups: 1) those without either radiographic knee OA (RKOA) or frequent knee symptoms (Sx) (n=542), 2) those with RKOA but without Sx (n=617), 3) those with Sx but without RKOA (n=220), and 4) those with both RKOA and Sx (n=543).

Table 2.

Associations of sociodemographic and health-related factors with meeting respective 150-min and 60-min weekly unbouted MVPA thresholds n = 1922

| Factors | Adjusted odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) from multivariate partial proportional odds model | |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 150-min weekly MVPA (reference: < 150-min) | ≥ 60-min weekly MVPA (reference: < 60-min) | |

| Women (reference: men) | 0.36 (0.29, 0.45) | 0.49 (0.39, 0.60) |

| Age (per 5 years) | 0.68 (0.63, 0.73) | 0.60 (0.56, 0.65) |

| BMI (per kg/m2) | 0.91 (0.89, 0.94) | 0.90 (0.88, 0.92) |

| Whites (reference: non-Whites) | 1.49 (1.09, 2.05) | 1.14 (0.86, 1.51) |

| College graduate or above (reference: non-college graduate) | 1.21 (0.83, 1.74) | 1.28 (0.95, 1.73) |

| Comorbidity Score (reference: 0) | ||

| 1 | 0.81 (0.60, 1.09) | 0.65 (0.50, 0.85) |

| ≥ 2 | 0.74 (0.52, 1.07) | 0.71 (0.51, 0.97) |

| Depressive symptoms (CES-D score ≥ 16) (reference: < 16) | 0.61 (0.43, 0.88) | 0.71 (0.52, 0.98) |

| Current working (reference: not working) | 1.36 (1.05, 1.76) | 1.46 (1.15, 1.84) |

| Radiographic knee OA (reference: no radiographic knee OA) | 1.03 (0.83, 1.29) | 0.98 (0.79, 1.22) |

| Frequent knee symptoms (reference: no frequent knee symptoms) | 0.77 (0.61, 0.96) | 0.85 (0.68, 1.05) |

MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity; BMI = body mass index; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale; OA = osteoarthritis

DISCUSSION

Among adults with or at elevated risk for knee OA, 44.1% men and 22.2% women met the 2018 PA Guidelines of 150-min weekly unbouted MVPA; 67.1% men and 50.3% women met the less demanding disability-free threshold of 60-minute weekly unbouted MVPA. Applying the less restrictive 2018 PA Guidelines, instead of the prior 2008 Guidelines, the proportion of men and women meeting 2018 Guidelines was more than double the 2008 Guideline attainment rate (i.e. 44.1% vs. 17.2% men and 22.2% vs. 9.2% women met the 2018 compared to the 2008 Guidelines of 150-min weekly bouted MVPA). Cross-sectional factors associated with not-meeting the 150-min weekly unbouted MVPA threshold were: being a woman, older age, higher BMI, non-Whites, depressive symptoms, not working, and frequent knee symptoms. Factors associated with not-meeting the 60-min threshold were: being a woman, older age, higher BMI, any comorbidity, depressive symptoms, and not working. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the prevalence and associated factors of 2018 PA Guideline attainment in adults with or at high risk for knee OA. A previous analysis of the US general population aged 18 years and older in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) cohort reported that 58.1% men and 32.6% women met the 2018 PA Guidelines.16 NHANES subgroup analysis indicated that 39.6% of older adults (men and women combined) aged 45–64 years and 12.3% of those aged 65+ years met the Guidelines.16 Likewise, time spent in daily MVPA were similarly low in both the OAI and NHANES cohorts.30 Compared to the general population, older adults with or at high risk for knee OA exhibited a similar pattern of gender disparity and comparable low rate of Guideline attainment.

Accounting for the total amount of minutes spent in MVPA, rather than those exclusively accumulated in bouts of at least 10 minutes, the recently updated 2018 PA Guidelines are more attainable and realistic for older adults with chronic knee complaints. Applying the 2018 vs. 2008 PA Guidelines to the same raw accelerometry data, we found that the proportion of guideline-adhering men and women increased by 2.5-fold. It is important to point out that this change is due to reclassification, not behavioral change. Despite this positive shift, it is concerning that 1 in 3 men and 1 in 2 women failed to meet even the less demanding minimum of 60-min weekly unbouted MVPA (i.e., the disability-free threshold), which is equivalent to approximately 10 minutes of brisk walking per day that does not even have to be continuous. Gender disparity in PA patterns has been extensively documented.14–16 Consistent with prior studies, our analysis affirmed that men are more likely to engage in the recommended amount of PA than women. Future studies may consider examining gender-specific determinants for maintaining sufficient PA. Consistent with previous findings in the general population,31–33 more advanced age and higher BMI were each strongly associated with not meeting Guidelines in our study. We found that, compared to non- Whites, Whites were more likely to achieve 150-min weekly MVPA. In two national samples of U.S. adults, Black and Hispanic Americans reported higher level of physical inactivity than their White counterparts.34,35 Similarly, Song and colleagues observed African Americans were substantially less likely than Whites to meet the 2008 PA Guidelines in the OAI cohort.36 Taken together, racial disparity in sufficient PA participation appears to be a universal public health challenge.

Our analysis showed that presence of any comorbidity was associated with reduced odds in attaining 60-min weekly unbouted MVPA. The relationship between comorbidity and physical inactivity is well established and likely bi-directional.37–39 For example, living with chronic diseases could limit one’s ability to engage in regular PA, while persistent inactivity increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity. Depression and physical inactivity also have a plausibly reciprocal association.40 Individuals with chronic knee pain are prone to depression and anxiety.41 Our findings that having depressive symptoms significantly lowered the odds of meeting both the PA Guidelines and the disability-free threshold provide further evidence for the PA-depression relationship and support mental health as a determinant for healthy PA in this population.

Interestingly, current working status was independently associated with meeting both the PA Guidelines and the disability-free threshold. Non-workers do not have opportunities to accumulate MVPA through daily commuting and occupational activities. Conversely, they may have more opportunities to integrate structured exercise and recreational/household PA into their daily routines. For individuals with joint pain who may potentially avoid movement and exercise for fear of symptom flares, employment could necessitate regular PA. This finding builds on previous general population studies. In the NHANES cohort, full-time employment was associated with greater accelerometer-measured PA in men, but not in women.42 Among adults aged 45 to 84 years followed up over a median of 9-year interval, transition to retirement was associated with a 10% decrease in MVPA minutes, 13% increase in recreational walking, 29% increase in household activity, and 15% increase in TV watching.43

Strategies that motivate/incentivize retired or non-working men and women to enroll in volunteer or recreational programs requiring active commuting or mobility may help increase PA levels in persons with knee OA.

Our multivariate analysis showed that self-report frequent knee symptoms was an independent factor associated with reduced odds of achieving the 150 weekly MVPA minute threshold, especially in women. Specifically, 16.1% of women with complaints of frequent knee symptoms met the PA Guidelines vs. 26.2 % of women without (Table 1). At first glance, the 10% difference may appear inconsequential. A 10% relative reduction in prevalence of insufficient PA by 2025 is the goal set by World Health Organization, as one of the nine global targets to improve the prevention and treatment of non-communicable diseases,44 thus supporting its public health significance. For adults with chronic knee complaints, incorporating symptom management in PA intervention programs may optimize benefits.

The study has several strengths. The OAI provides a large, well-characterized, community-recruited, multi-site sample of men and women with or at elevated risk for knee OA. To consider the entire spectrum of knee OA disease status, we included the at-risk cohort, which represents the early stage of the disease.45,46 We used objectively measured PA by accelerometry to minimize biases of imprecise recall and social desirability by self-report. In addition to the recommended 2018 MVPA threshold, we assessed an evidence-based, functionally-important 60-minute threshold.

The following limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. We applied the federally recommended 2018 PA Guidelines, which were developed predominantly using self-reported PA measures, to accelerometry-measured MVPA minutes in the OAI. In the absence of established accelerometer-based PA Guidelines, most researchers have used this universally accepted PA Guidelines for classifying Guideline attainment by either self-reported or device-measured PA in a wide range of population.26,47,48 With the rapidly growing use of tracking devices, future development of objectively-recorded PA Guidelines could overcome this inherent limitation. The MVPA activity count cutpoint of 2020 counts/minute was chosen based on current best practice for large epidemiological studies, such as NHANES26 and OAI.27 This threshold was benchmarked against activities that require energy expenditure of ≥ 3 METs (Metabolic Equivalent of Task) in the general population.26 There is no evidence that adults with knee OA walked at a slower pace than those without,49,50 it is therefore reasonable to assume comparable energy expenditure between these two groups.

Finally, PA occurring in water or during cycling was not captured by accelerometry, which may lead to underestimated PA. However, our prior examination indicated that OAI participants spent little time in water or cycling activities.36

In conclusion, 44.1% men and 22.2% women with or at elevated risk for knee OA met the updated 2018 PA Guidelines of 150-min weekly unbouted MVPA. Applying the 2018 PA Guidelines, instead of the prior 2008 Guidelines, to reassess previously collected accelerometer data for Guideline attainment, the proportion of men and women meeting Guidelines increased by 2.5-fold. Since it is easier to accumulate non-bouted than bouted MVPA minutes, the more attainable 2018 PA Guidelines may motivate individuals with chronic knee symptoms to initiate and maintain sufficient PA.

Approximately 33% of men and 50% of women failed to accrue even 60 unbouted minutes of MVPA per week. Being a woman, older, non-White, and not working; and having higher BMI, depressive symptoms, and frequent knee symptoms were each associated with not meeting the 2018 PA Guidelines. Being a woman, older, and not working; and having higher BMI, any comorbidity, and depressive symptoms were each associated with not meeting the disability-free threshold of 60-min weekly unbouted MVPA. PA-promoting interventions may consider addressing potentially modifiable factors, such as BMI, mental health, and knee pain, to optimize benefits in the setting of knee OA.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank OAI participants and study site investigators and coordinators for their contribution to the study.

Funding information: The work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institute of Health (R01-AR054155, P60-AR064464, and P30-AR072579)

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The institutional Review Board at each site approved the study.

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to the reported work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Dragomir AD, Woodard J, et al. Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(1):172–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1323–1330. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nüesch E, Dieppe P, Reichenbach S, Williams S, Iff S, Jüni P. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d1165. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, Arden NK, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22(3):363–388. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall AJ, Stubbs B, Mamas MA, Myint PK, Smith TO. Association between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(9):938–946. doi: 10.1177/2047487315610663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louati K, Vidal C, Berenbaum F, Sellam J. Association between diabetes mellitus and osteoarthritis: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. RMD Open. 2015;1(1):e000077. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Wang J, Liu X. Association between hypertension and risk of knee osteoarthritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(32). doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. Washington DC: U.S. DHHS; 2018. https://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loprinzi PD, Davis RE. Bouted and non-bouted moderate-to-vigorous physical activity with health-related quality of life. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:46–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke J, Janssen I. Sporadic and bouted physical activity and the metabolic syndrome in adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(1):76–83. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829f83a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone RC, Baker J. Painful choices: A qualitative exploration of facilitators and barriers to active lifestyles among adults with osteoarthritis. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36(9):1091–1116. doi: 10.1177/0733464815602114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanavaki AM, Rushton A, Efstathiou N, Alrushud A, Klocke R, Abhishek A, et al. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017042. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunlop DD, Song J, Hootman JM, Nevitt MC, Semanik PA, Lee J, et al. One Hour a Week: Moving to Prevent Disability in Adults With Lower Extremity Joint Symptoms. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):664–672. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawkins MS, Storti KL, Richardson CR, King WC, Strath SJ, Holleman RG, et al. Objectively measured physical activity of USA adults by sex, age, and racial/ethnic groups: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zenko Z, Willis EA, White DA. Proportion of Adults Meeting the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans According to Accelerometers. Front Public Health. 2019;7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Lancet Public Health. Time to tackle the physical activity gender gap. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(8):e360. doi:10.1016/S2468–2667(19)30135–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osteoarthritis Initiative. Protocol for the cohort study. oai.epi-ucsf.org/datarelease/docs/StudyDesignProtocol.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 19.Jarrett H, Fitzgerald L, Routen AC. Interinstrument Reliability of the ActiGraph GT3X+ Ambulatory Activity Monitor During Free-Living Conditions in Adults. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(3):382–387. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClain JJ, Sisson SB, Tudor-Locke C. Actigraph accelerometer interinstrument reliability during free-living in adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(9):1509–1514. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3180dc9954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welk GJ, Schaben JA, Morrow JR. Reliability of accelerometry-based activity monitors: a generalizability study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(9):1637–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trost SG, Mciver KL, Pate RR. Conducting Accelerometer-Based Activity Assessments in Field-Based Research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(11):S531. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly LA, McMillan DG, Anderson A, Fippinger M, Fillerup G, Rider J. Validity of actigraphs uniaxial and triaxial accelerometers for assessment of physical activity in adults in laboratory conditions. BMC Med Phys. 2013;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1756-6649-13-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendelman D, Miller K, Baggett C, Debold E, Freedson P. Validity of accelerometry for the assessment of moderate intensity physical activity in the field. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(9 Suppl):S442–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bouten CV, Westerterp KR, Verduin M, Janssen JD. Assessment of energy expenditure for physical activity using a triaxial accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26(12):1516–1523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–188. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song J, Semanik P, Sharma L, Chang RW, Hochberg MC, Mysiw WJ, et al. Assessing physical activity in persons with knee osteoarthritis using accelerometers: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62(12):1724–1732. doi: 10.1002/acr.20305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vilagut G, Forero CG, Barbaglia G, Alonso J. Screening for depression in the general population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thoma LM, Dunlop D, Song J, Lee J, Tudor-Locke C, Aguiar EJ, et al. Are older adults with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis less active than the general population?: Analysis from the Osteoarthritis Initiative and NHANES. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70(10):1448–1454. doi: 10.1002/acr.23511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson KB. Physical Inactivity Among Adults Aged 50 Years and Older — United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6536a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keadle SK, McKinnon R, Graubard BI, Troiano RP. Prevalence and trends in physical activity among older adults in the United States: A comparison across three national surveys. Prev Med. 2016;89:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dyck DV, Cerin E, Bourdeaudhuij ID, Hinckson E, Reis RS, Davey R, et al. International study of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time with body mass index and obesity: IPEN adult study. Int J Obes. 2015;39(2):199–207. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Andersen RE, Carter-Pokras O, Ainsworth BE. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00105-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall SJ, Jones DA, Ainsworth BE, Reis JP, Levy SS, Macera CA. Race/ethnicity, social class, and leisure-time physical inactivity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(1):44–51. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000239401.16381.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song J, Hochberg MC, Chang RW, Hootman JM, Manheim LM, Lee J, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in physical activity guidelines attainment among people at high risk of or having knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(2):195–202. doi: 10.1002/acr.21803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ . Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(2):1143–1211. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brawner CA, Churilla JR, Keteyian SJ. Prevalence of Physical Activity Is Lower among Individuals with Chronic Disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(6):1062–1067. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barker J, Smith Byrne K, Doherty A, Foster C, Rahimi K, Ramakrishnan R, et al. Physical activity of UK adults with chronic disease: cross-sectional analysis of accelerometer-measured physical activity in 96 706 UK Biobank participants. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(4):1167–1174. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindwall M, Larsman P, Hagger MS. The reciprocal relationship between physical activity and depression in older European adults: a prospective cross-lagged panel design using SHARE data. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2011;30(4):453–462. doi: 10.1037/a0023268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawker GA, Gignac MAM, Badley E, Davis AM, French MR, Li Y, et al. A longitudinal study to explain the pain-depression link in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(10):1382–1390. doi: 10.1002/acr.20298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Domelen DR, Koster A, Caserotti P, Brychta RJ, Chen KY, McClain JJ, et al. Employment and physical activity in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones SA, Li Q, Aiello AE, O’Rand AM, Evenson KR. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Retirement: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6):786–794. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.WHO | Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020. WHO; http://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/. Accessed November 30, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Favero M, Ramonda R, Goldring MB, Goldring SR, Punzi L. Early knee osteoarthritis. RMD Open. 2015;1(Suppl 1):e000062. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma L, Nevitt M, Hochberg M, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Crema M, et al. Clinical significance of worsening versus stable preradiographic MRI lesions in a cohort study of persons at higher risk for knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):1630–1636. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tudor-Locke C, Brashear MM, Johnson WD, Katzmarzyk PT. Accelerometer profiles of physical activity and inactivity in normal weight, overweight, and obese U.S. men and women. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:60. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thraen-Borowski KM, Gennuso KP, Cadmus-Bertram L. Accelerometer-derived physical activity and sedentary time by cancer type in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunlop DD, Song J, Semanik PA, Sharma L, Chang RW. Physical activity levels and functional performance in the Osteoarthritis Initiative: a graded relationship. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(1):127–136. doi: 10.1002/art.27760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bohannon RW. Population representative gait speed and its determinants. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2001. 2008;31(2):49–52. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200831020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]