Abstract

Averrhoa carambola is commonly known as star fruit because of its peculiar shape, and its fruit is a rich source of minerals and vitamins. It is also used in traditional medicines in countries such as India, China, the Philippines, and Brazil for treating various ailments, including fever, diarrhea, vomiting, and skin disease. Here, we present the first draft genome of the Oxalidaceae family, with an assembled genome size of 470.51 Mb. In total, 24,726 protein-coding genes were identified, and 16,490 genes were annotated using various well-known databases. The phylogenomic analysis confirmed the evolutionary position of the Oxalidaceae family. Based on the gene functional annotations, we also identified enzymes that may be involved in important nutritional pathways in the star fruit genome. Overall, the data from this first sequenced genome in the Oxalidaceae family provide an essential resource for nutritional, medicinal, and cultivational studies of the economically important star-fruit plant.

Subject terms: Plant evolution, Plant genetics

Introduction

The star-fruit plant (Averrhoa carambola L.), a member of the Oxalidaceae family, is a medium-sized tree that is distinguished by its unique, attractive star-shaped fruit (Supplementary Fig. 1). A. carambola is widely distributed around the world, especially in tropical countries such as India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, and is considered an important species; thus, it is extensively cultivated in Southeast Asia and Malaysia1,2. It is also a popular fruit in the markets of the United States, Australia, and the South Pacific Islands3. Star fruits have a unique taste, with a slightly tart, acidic (in smaller fruits) or sweet, mild flavor (in large fruits). Star fruit is a good source of various minerals and vitamins and is rich in natural antioxidants such as vitamin C and gallic acid. Moreover, the presence of high amounts of fiber in these fruits aids in absorbing glucose, retarding glucose diffusion into the bloodstream and controlling the blood glucose concentration.

In addition to its use as a food source, star fruit is utilized as an herb in India, Brazil, and Malaysia and is widely used in traditional Chinese medicine preparations4 as a remedy for fever, asthma, headache, and skin diseases5. Several studies have demonstrated the presence of various phytochemicals, such as saponins, flavonoids, alkaloids, and tannins, in the leaves, fruits, and roots of star-fruit plants6,7; these compounds are known to confer antioxidant and specific healing properties. A study by Cabrini et al.5 indicated that the ethanolic extract from A. carambola is highly effective in minimizing the symptoms of ear swelling (edema) and cellular migration in mice. A flavonoid compound (apigenin-6-C-β-fucopyranoside) isolated from A. carambola leaves showed anti-hyperglycemic action in rats, and might show potential for use in the treatment and prevention of diabetes8. Moreover, 2-dodecyl-6-methoxycyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione (DMDD) extracted from the roots of A. carambola exhibits potential benefits in the treatment of obesity, insulin resistance, and memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease9,10.

Although A. carambola plays very significant roles in traditional medicine applications, there are very limited studies on A. carambola at the genetic level, mainly due to a lack of genome information. Therefore, filling this genomic gap will help researchers to fully explore and understand this agriculturally important plant. As a part of the 10KP project11,12, the draft genome of A. carambola collected from the Ruili Botanical Garden in Yunnan, China, was assembled in this study using an advanced 10X genomics technique to further elucidate the evolution of the Oxalidaceae family. A fully annotated genome of A. carambola will serve as a foundation for pharmaceutical applications of the species and the improvement of breeding strategies for the star-fruit plant.

Results

Genome assembly and evaluation

Based on k-mer analysis, a total of 35,655,285,391 k-mers were used, with peak coverage of 75. The A. carambola genome was estimated to be ~475 Mb in size (Supplementary Fig. 2). To perform genome assembly, a total of 156 Gb of clean reads were utilized by Supernova v2.1.113. The final assembly contained 69,402 scaffold sequences, with an N50 of 2.76 Mb, and 78,313 contig sequences, with an N50 of 44.84 Kb, for a total assembly size of 470.51 Mb (Table 1). Completeness assessment was performed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) version 3.0.114 with Embryophyta odb9. The results showed that 1327 (92.20%) of the expected 1440 conserved plant orthologs were detected as complete (Supplementary Table 1). To further evaluate the completeness of the assembled genome, we performed short read mapping using clean raw data with BWA-MEM software15. In total, 943,278,896 (99.12%) reads could be mapped to the genome, and 88.13% of them were properly paired (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1.

Statistics of genome assembly.

| Contig | Scaffold | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | Number | Size (bp) | Number | |

| N90a | 5420 | 12,457 | 7033 | 3988 |

| N80 | 13,875 | 7548 | 39,210 | 608 |

| N70 | 23,325 | 5165 | 34,6109 | 131 |

| N60 | 33,460 | 3619 | 1,307,770 | 60 |

| N50 | 44,841 | 2503 | 2,757,598 | 35 |

| Longest | 717,770 | – | 14,768,062 | – |

| Total size | 431,262,337 | – | 470,508,511 | – |

| Total number (≥2 kb) | – | 18,820 | – | 10,777 |

| Total number (≥100 bp) | – | 78,313 | – | 69,402 |

aNxx length is the maximum length (L) such that xx% of all nucleotides lie within contigs (or scaffolds) with a size of at least L.

Genome annotation

A total of 68.15% of the assembled A. carambola genome was composed of repetitive elements (Supplementary Table 3). Among these repetitive sequences, LTRs were the most abundant, accounting for 61.64% of the genome. DNA class repeat elements represented 4.19% of the genome; LINE and SINE classes accounted for 0.28% and 0.016% of the assembled genome, respectively. For gene prediction, we combined homology-based and de novo-based approaches and obtained a non-redundant set of 24,726 gene models with 4.11 exons per gene on average. The gene length was 3457 bp on average, while the average exon and intron lengths were 215 and 827 bp, respectively. The gene model statistical data compared with seven other closely related species are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. To evaluate the completeness of the gene models for A. carambola, we used BUSCO with Embryophyta odb9. A total of 1281 (88.9%) complete orthologs were detected from the predicted star fruit gene sets (Supplementary Table 4).

Functions were assigned to 16,490 (66.69%) genes. These protein-coding genes were then subjected to further exploration against the KEGG, NR, and COG protein sequence databases16, in addition to the SwissProt and TrEMBL databases17, and InterProScan18 was finally used to identify domains and motifs (Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Fig. 4). Noncoding RNA genes in the assembled genome were also annotated. We predicted 759 tRNA, 1341 rRNA, 90 microRNA (miRNA), and 2039 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) genes in the assembled genome (Supplementary Table 6).

Since star fruit is an important cultivated plant, the identification of disease resistance genes was one of the focuses of our study. Nucleotide-binding site (NBS) genes play an important role in pathogen defense and the cell cycle. We identified a total of 80 non-redundant NBS-encoding orthologous genes in the star fruit genome (Supplementary Table 7). Among these genes, TIR (encoding the toll interleukin receptor) motif was found to be significantly smaller than in other eudicot plants, except for cocoa. Unlike other plants, the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) motif was not the most or second most common motif in the NBS gene family in star fruit19.

Genome evolution

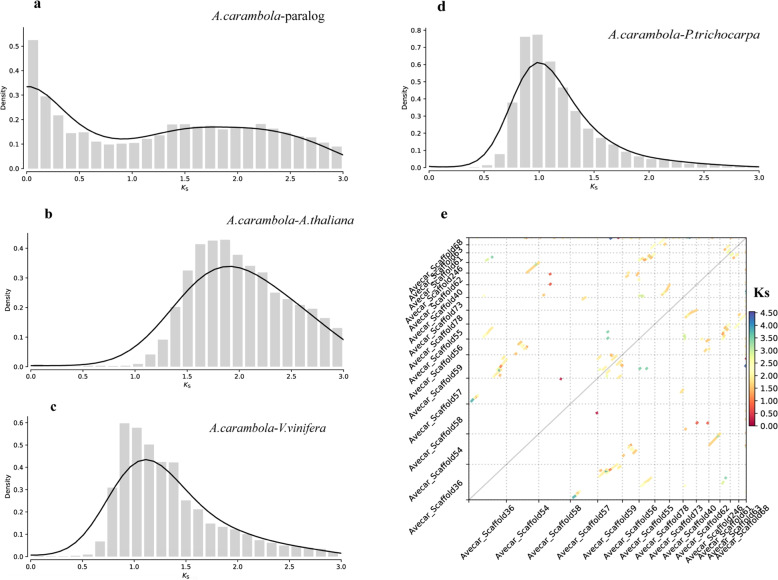

The characterization of the star fruit genome can provide necessary data for further analyzing the evolutionary history of Oxalidaceae. A γ whole-genome triplication event affected over 75% of extant angiosperms and was associated with the early diversification of the core eudicots. To investigate evolutionary events at the genomic level in star fruit, we identified 1134 paralogous gene families on the basis of the 24,726 gene models. The synonymous substitution rates (Ks) in the duplicated genes (Ks = 1.9) suggested that an ancient γ event occurred in star fruit (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, we assessed the intergenomic collinearity among the Arabidopsis20, poplar21, and grape22 genomes and identified relationships among star fruit orthologues. The mean Ks values from the one-to-one orthology analysis of star fruit in relation to Arabidopsis, poplar, and grape were 1.8, 1.0, and 1.2, respectively (Fig. 1b–d). The results confirmed the shared ancient whole-genome duplications (WGDs) event between the four species. Moreover, we generated whole-genome syntenic dotplots of star fruit based on the Ks value (Fig. 1e). Over 50% of the syntenic blocks shared a Ks rate between 1.0 and 2.0, and only ~10% of the gene pairs exhibited a Ks below 1.0, which indicated that no recent WGDs have occurred in the star fruit genome.

Fig. 1. The analysis of A. carambola whole-genome duplications.

The distribution of synonymous substitution rate (Ks) distance values observed for a A. carambola-paralog, b A. carambola–A. thaliana ortholog, c A. carambola–V. vinifera ortholog, and d A. carambola–P. trichocarpa ortholog. e The A. carambola paralog colinear blocks are colored according to Ks values.

Gene family analysis and phylogenetic tree

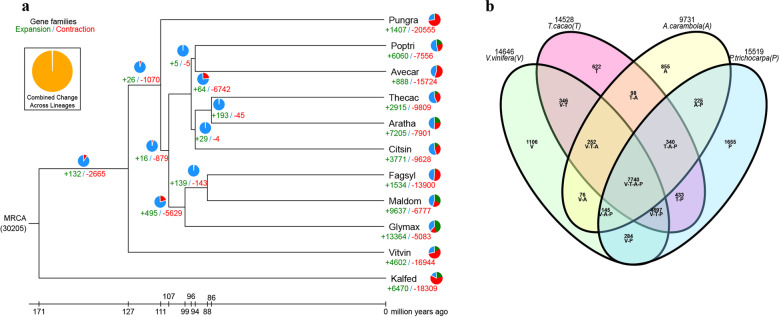

We performed A. carambola gene family analysis using OrthoMCL software23 with protein and nucleotide sequences from A. carambola and 10 other plant species (A. thaliana, C. sinensis, F. sylvatica, G. max, K. fedtschenkoi, M. domestica, P. granatum, P. trichocarpa, T. cacao, V. vinifera) based on an all-versus-all BLASTP alignment with an E-value cutoff of 1e−05. The 24,726 predicted protein-coding genes in A. carambola were assigned to 9731 gene families consisting of 15,301 genes, while 9425 genes were not organized into groups and were unique to A. carambola (Supplementary Table 8, Fig. 2b). In total, 163 single-copy orthologs corresponding to the 11 species were extracted from the clusters and used to construct the phylogenetic tree. The constructed tree topology supported the APG IV24 system in which Oxalidales (A. carambola) and Malpighiales (P. trichocarpa) are sister clades that belong to the same cluster (rosids). Based on the phylogenetic tree, A. carambola was estimated to have separated from P. trichocarpa, V. vinifera, and K. fedtschenkoi approximately 94.5, 110.2, and 126.3 Mya, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 2. Gene family analysis and phylogenetic tree construction.

a Phylogenetic tree showing the sizes of expanded and contracted gene families. Pungra: P. granatum; Poptri: P. trichocarpa; Avecar: A. carambola; Thecac: T. cacao; Aratha: A. thaliana; Citsin: C. sinensis; Fagsyl: F. sylvatica; Maldom: M. domestica; Glymax: G. max; Vitvin: V. vinifera; Kalfed: K. fedtschenkoi. b Venn diagram of the number of shared gene families within A. carambola, V. vinifera, T. cacao, and P. trichocarpa.

We also analyzed the expansion and contraction of the gene families between species using CAFÉ25. The results showed that 888 gene families were substantially expanded and that 15,724 gene families were contracted in A. carambola (Fig. 2a). In total, 2916 and 6057 genes identified in A. carambola came from expanded and contracted families, respectively, where contraction was approximately two times more common than expansion.

Gene ontology (GO) and KEGG functional enrichment analyses were subsequently performed for all expanded gene families. The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results are shown in Table 2, and the GO-enrichment results are listed in Supplementary Table 9. In a previous study, several flavonoids were isolated from the fresh fruit of A. carambola, which are known to reduce harmful inflammation26. In our study, the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway was found to be significantly enriched among the expanded families. Terpenoids are yet another important type of compound that has been isolated from star fruit27 and has been proven to exhibit anti-inflammatory activities. A. carambola likely synthesizes terpenoids via the diterpenoid biosynthesis pathway.

Table 2.

Enriched KEGG pathways of unique genes of A. carambola showing expansion.

| Pathway ID | KEGG description | Adjusted P-value (≤0.05) | Number of genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| map03020 | RNA polymerase | 3.51E–09 | 30 |

| map00904 | Diterpenoid biosynthesis | 1.00E–05 | 18 |

| map00240 | Pyrimidine metabolism | 3.16E–05 | 34 |

| map01100 | Metabolic pathways | 7.17E–05 | 234 |

| map00901 | Indole alkaloid biosynthesis | 7.17E–05 | 15 |

| map00230 | Purine metabolism | 7.17E–05 | 36 |

| map00565 | Ether lipid metabolism | 0.00014092 | 14 |

| map01110 | Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites | 0.00038039 | 142 |

| map02010 | ABC transporters | 0.00080624 | 20 |

| map00902 | Monoterpenoid biosynthesis | 0.00116462 | 9 |

| map00460 | Cyanoamino acid metabolism | 0.00270665 | 18 |

| map00941 | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 0.03063434 | 17 |

| map00190 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.0354555 | 19 |

| map00940 | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 0.0354555 | 32 |

| map00062 | Fatty acid elongation in mitochondria | 0.0354555 | 7 |

| map00563 | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol(GPI)-anchor biosynthesis | 0.03937265 | 8 |

| map00040 | Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 0.0426558 | 21 |

Genes specifically involved in star fruit nutrition pathways

Star fruit is an excellent source of various minerals and vitamins, especially natural antioxidants, such as l-ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and riboflavin (vitamin B2)1,26. Through the ortholog searches in KEGG pathways, we identified enzymes that are potentially involved in the vitamin C and vitamin B2 biosynthesis pathways in A. carambola.

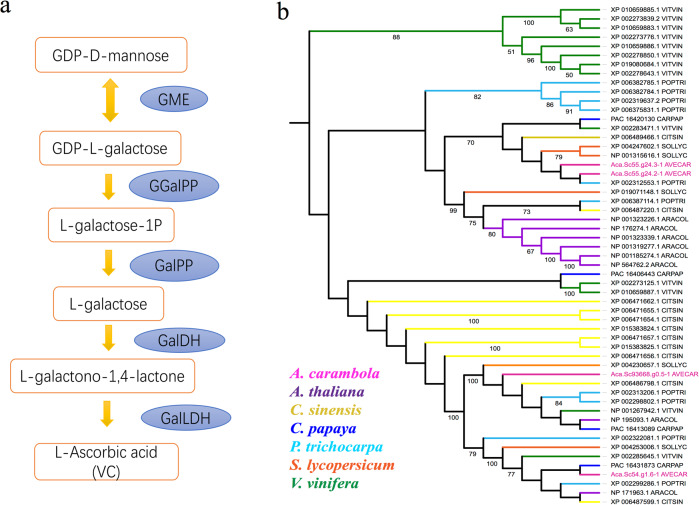

In a previous report, a major component of plant ascorbate was reported to be synthesized through the l-galactose pathway28, in which GDP-d-mannose is converted to l-ascorbate through four successive intermediates, as summarized in Fig. 3a. Laing et al. 29 reported the identification of l-galactose guanylyltransferase-encoding homologous genes from Arabidopsis and kiwifruit that encode enzymes that catalyze the conversion of GDP-l-galactose to l-galactose-1-P. In this study, five necessary enzymes (GalDH, GalLDH, GGalPP, GalPP, and GME) involved in the vitamin C pathway were identified, suggesting the possibility of ascorbic acid synthesis in star fruit (Table 3). For l-galactose dehydrogenase (GalDH), we identified four paralogous genes in the star fruit genome. The copy number of GalDH genes in star fruit is close to that in tomato (5) and papaya (4) but approximately half that in other species (10 in poplar, 11 in orange, 8 in Arabidopsis, and 13 in grape, Supplementary Table 12). Further evolutionary analysis showed three clusters in the phylogenetic tree, and the most ancient cluster comprised all the grape genes. Among the other two sister clusters, one is ancient and comes from poplar, including four genes, and the other is closer to orange, including seven genes. The four genes in star fruit are divided into two clusters and were recently separated from their ancestors (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Genes involved in vitamin C metabolism.

a A proposed model for l-ascorbic acid biosynthesis pathways in star fruit. Genes identified as being involved in the pathways are shown in blue circles. b Phylogenetic analysis of the GalDH gene family in A. carambola (rose red), A. thaliana (purple), C. sinensis (yellow), C. papaya (blue), P. trichocarpa (sky blue), S. lycopersicum (orange), and V. vinifera (green).

Table 3.

List of genes involved in the vitamin C and vitamin B2 pathways.

| Pathway | Enzyme | Description | Copy numbers | Gene ID | Protein (AA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C pathway | GalDH | l-galactose dehydrogenase | 4 | Aca.sc093668.g0.5 | 332 |

| Aca.sc000054.g1.6 | 334 | ||||

| Aca.sc000055.g24.2 | 351 | ||||

| Aca.sc000055.g24.3 | 594 | ||||

| GalLDH | l-galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase | 5 | Aca.sc000059.g19.35 | 601 | |

| Aca.sc000229.g0.29 | 603 | ||||

| Aca.sc000078.g43.5 | 598 | ||||

| Aca.sc100684.g0.3 | 99 | ||||

| Aca.sc102574.g0.3 | 99 | ||||

| GGalPP | GDP-l-galactose phosphorylase | 3 | Aca.sc150475.g0.5 | 275 | |

| Aca.sc150564.g0.4 | 288 | ||||

| Aca.sc098705.g0.4 | 410 | ||||

| GalPP | l-galactose-1-phosphate phosphatase | 2 | Aca.sc006151.g1 | 181 | |

| Aca.sc000246.g13.57 | 360 | ||||

| GME | GDP-d-mannose-3′,5′-epimerase | 2 | Aca.sc096116.g0.5 | 383 | |

| Aca.sc000061.g13.42 | 383 | ||||

| Vitamin B2pathway | RIB3 | 3,4-dihydroxy 2-butanone 4-phosphate synthase | 3 | Aca.sc000063.g38.15 | 545 |

| Aca.sc000056.g65.27 | 572 | ||||

| Aca.sc000071.g11.34 | 590 | ||||

| RIB4 | 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase | 1 | Aca.sc023103.g76.2 | 185 | |

| RIB5 | riboflavin synthase | 1 | Aca.sc000036.g2.16 | 343 | |

| RFK | riboflavin 5′-phosphotransferase | 1 | Aca.sc000058.g77.42 | 539 | |

| FLAD1 | FMN adenylyltransferase | 1 | Aca.sc000058.g25.58 | 520 |

GalDH l-galactose dehydrogenase, GalLDH l-galactono-1,4-lactone dehydrogenase, GGalPP GDP-l-galactose phosphorylase, GalPP l-galactose-1-phosphate phosphatase, GME GDP-d-mannose-3′,5′-epimerase.

We also identified possible enzymes involved in the riboflavin (vitamin B2) biosynthesis pathway in star fruit (Fig. 4a, Table 3). Through catalysis by RIB3, RIB4, and RIB5, riboflavin can ultimately be produced from the d-ribulose 5-phosphate compound. Furthermore, in the investigation of the possible biosynthesis pathway of the special product oxalate in star fruit, we identified three enzymes, citrate synthase (CS), isocitrate lyase (aceA), and aconitate hydratase (ACO), that can potentially catalyze the transformation of oxalacetic acid to glyoxylate within the glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism pathway (Supplementary Table 10).

Fig. 4.

Identification of genes involved in the (a) riboflavin and (b) flavonoid biosynthesis pathways. Genes identified as being involved in the two pathways are shown in blue circles. FLAD1 FMN adenylyltransferase, RIB3 3,4-dihydroxy 2-butanone 4-phosphate synthase, RIB4 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase, RIB5 riboflavin synthase, RFK riboflavin 5′-phosphotransferase, ANR anthocyanidin reductase, ANS leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase, CCOAMT caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase, CHI chalcone isomerase, CHS chalcone synthase, CYP75A flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase, CYP75B1 flavonoid 3′-monooxygenase, CYP98A coumaroylquinate 3′-monooxygenase, DFR flavanone 4-reductase, F3H naringenin 3-dioxygenase, HCT shikimate O-hydroxycinoyltransferase.

In the A. carambola gene family analysis, the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the expanded gene families revealed that 17 genes participate in the flavonoid synthesis pathway (P-value = 0.03, Table 3). Previous studies have proved that flavonoids can be isolated from A. carambola and other plants from the Oxalidaceae family1,9,26,30–33. Here, we identified 11 enzymes that could be potentially involved in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 11). The two enzymes in the pathway showing the highest copy numbers are shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase (HCT) and chalcone synthase (CHS), with 23 and 21 copies, respectively. Among the end-point products, apigenin, cyanidin, epicatechin, and quercetin have been extracted from the leaves, fruits or bark of A. carambola in previous studies6,34–36.

Discussion

This study presents the first draft genome in the Oxalidaceae family. The sequenced species, A. carambola (star fruit), is widely cultivated and utilized as an edible fruit and serves as an important source of minerals and vitamins, in addition to presenting phytomedicinal properties. The assembled genome size was 470.51 Mb, with a scaffold N50 of 2.76 Mb. We cannot compare this genome size with those of other species in this family, but we found similar genome sizes in the closest order Malpighiales of 434.29 Mb in Populus trichocarpa and 350.62 Mb in Ricinus communis. However, the chromosome-level genome will be required to better understand the diploid character of this species.

In total, 24,726 gene models were identified from A. carambola. This gene number is relatively smaller than those from earlier reports for A. thaliana, P. trichocarpa, or T. cacao. The length distribution of the exons of the predicted star fruit proteins was consistent with those in other species, although the predicted intron and CDS lengths tended to be shorter than those in other species (Supplementary Fig. 3). The proportion of predicted genes containing an InterPro functional domain was 52.3%, and the proportion that could be aligned with the NCBI nr database (66.4%) was the highest among all databases. It is likely that A. carambola is the only species in the Oxalidaceae family whose genome has been assembled so far; there might be some evolutionarily unique genes in this family remaining to be annotated.

We subsequently performed gene family analysis together with the other 10 species and identified the significant expansion of 888 gene families containing 2916 unique genes in A. carambola. These genes were significantly enriched (P-value ≤ 0.05) within 28 GO classes, including 18 biological process, 2 cellular component, and 8 molecular function categories (Supplementary Table 6). The biological process of DNA binding contained the most genes (60) within the expanded families. Within the significantly enriched biological processes, the defense response to fungus might be related to the antimicrobial property of star fruits identified in previous studies1. On the other hand, we found that oxidoreductase activity was enriched in the molecular function GO class, which could be one of the potential reasons for the antioxidant activity of star fruits.

The genome evolution analysis indicated that star fruit only shared an ancient γ event, and no recent WGD was observed. In a genome evolution study of poplar, which belongs to Malpighiales, the existence of a hexaploidization event and recent duplication were reported21. This result could partially explain why star fruit has half the number of gene sets compared to poplar.

Moreover, among the enriched KEGG pathways, we identified enzymes involved in nutritional metabolic pathways, including the vitamin C, vitamin B2, oxalate, and flavonoid pathways. Although potential functional enzymes have been identified from the genome, these functional pathways should be verified by experimental studies in the future.

In summary, it can be expected that this draft genome will facilitate the elucidation of the development of specific important traits in star fruit plants, such as the biosynthesis pathways of pharmacologically active metabolites, and will contribute to the improvement of breeding strategies for star fruit plants.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and sequencing

Leaf samples of A. carambola were collected from the Ruili Botanical Garden, Yunnan, China. Genomic DNA was extracted by using the cetyl-triethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method37. 10X Genome sequencing was performed to obtain high-quality reads. High-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA was loaded onto a Chromium Controller chip with 10X Chromium reagents and gel beads, and the rest of the procedures were carried according to the manufacturer’s protocol38. Then, the BGISEQ-500 platform was used to produce 2 × 150 bp paired-end sequences, generating a total of 206.28 Gb of raw data. The raw reads were filtered using SOAPfilter v2.2 with the following parameters: “-q 33 -i 600 -p -l -f -z -g 1 -M 2 -Q 20”. After filtering low-quality reads, ~114.42 Gb of clean data (high-quality reads >Q35) remained for the next step.

Estimation of A. carambola genome size

All 114.42 Gb clean reads obtained from the BGISEQ-500 platform were subjected to 17 kmer frequency distribution analysis with Jellyfish39 using the parameters “-k 17 -t 24”. The frequency graph was drawn, and the A. carambola genome size was calculated using the formula: genome size = k-mer_Number/Peak_Depth.

De novo genome assembly

The linked read data were assembled using Supernova v2.1.1 software13 using the “--localcores = 24 --localmem=350 --max reads 280000000” parameter. To fill the scaffold gaps, GapCloser version 1.1240 was used with the parameters “-t 12 -l 155”. Finally, the total assembled length of the A. carambola genome was 470.51 Mb, with a scaffold N50 of 275.76 Kb and a contig N50 of 44.84 Kb.

Repeat annotation

For transposable element annotation, RepeatMasker v3.3.041 and RepeatProteinMasker v3.3.041 were applied against Repbase v16.1042 to identify known repeats in the A. carambola genome. Tandem repeats were identified using Tandem Repeats Finder v4.07b43. De novo repeat identification was conducted using the RepeatModeler v1.0.544 and LTR_FINDER v1.0545 programs, followed by RepeatMasker v3.3.041 to obtain the final results.

Gene prediction

Prior to the gene prediction analysis, we masked the repetitive regions of the genome. MAKER-P v2.3146 was utilized to predict protein-coding genes based on homology and de novo prediction evidence. For homology-based prediction, the protein sequences of Theobroma cacao, Prunus persica, Prunus mume, Prunus avium, Populus trichocarpa, Populus euphratica, and Arabidopsis thaliana were aligned against the A. carambola genome using BLAT47. Then, the gene structure was predicted using GeneWise48. To optimize different ab initio gene predictors, we constructed a series of training sets for de novo prediction data. Complete gene models according to homology evidence were picked for training with the Augustus tool49. Genemark-ES v4.2150 was self-trained using the default criteria. The first round of MAKER-P analysis was also run using the default parameters on the basis of the above evidence, with the exception of “protein2genome”, which was set to “1”, yielding only protein-supported gene models. SNAP51 was then trained with these gene models. The default parameters were used to run the second and final rounds of MAKER-P, generating the final gene models.

Functional annotation

The predicted gene models were functionally annotated by aligning their protein sequences against the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)52, Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG)16, SwissProt17, TrEMBL, and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant (NR) protein databases with BLASTP (E-value ≤ 1e–05). Protein motifs and domains were identified by comparing the sequences against various domain databases, including the PFAM, PRINTS, PANTHER, ProDom, PROSITE, and SMART databases, using InterProScan v5.2118. For ncRNA annotation, tRNA genes were identified with tRNAscan-SE v1.2353. For the identification of rRNA genes, we aligned the assembled data against the rRNA sequences of A. thaliana using BLASTN (E-value ≤ 1e–05). miRNAs and snRNAs were predicted by using INFERNAL54 software against the Rfam database55.

To classify the NBS domains in the star fruit protein sequences, we used hidden Markov models (HMM) to search for the Pfam NBS (NB-ARC) family PF00931 with an E-value cutoff of 1.0. To detect TIR domains, the amino acid sequences were also screened by using the HMM model Pfam TIR PF01582 (E-value ≤ 1.0). Moreover, to identify LRR motifs, we performed an HMM search for Pfam LRR models (E-value ≤ 1.0) against star fruit NBS-encoding amino acid sequences.

To compare the orthologous genes in the vitamin C, vitamin B2, flavonoid and oxalate pathways between other plant species (P. trichocarpa, C. sinensis, A. thaliana, S. lycopersicum, C. papaya, and V. vinifera), we also annotated the protein sequences by aligning them against the KEGG database52 with BLASTP (E-value ≤ 1e–05) and then performed filtering according to Pfam domains annotated using InterProScan v5.2118.

Genome evolution

The genome sequences used for orthology analysis were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) for A. thaliana (GCA_000001735.2), V. vinifera (GCA_000003745.2), and P. trichocarpa (GCA_000002775.3). Next, we used wgd software56 to perform the Ks distribution analysis. The analyses of paralogous gene families and one-to-one orthologs were performed using the “wgd mcl” command. Then, the Ks distribution for a set of paralogous families or one-to-one orthologs was constructed using “wgd ksd”. Next, we applied the “wgd kde” command for the fitting of kernel density estimates (KDEs). Finally, the colinear blocks of the A. carambola paralog were identified by I-ADHoRe57 and colored according to their median Ks value.

Gene family construction and phylogenetic analysis

For gene family analysis, OrthoMCL23 software was utilized to construct the orthologous gene families of all the protein-coding genes of A. carambola and other 10 sequenced plant species (A. thaliana, C. sinensis, F. sylvatica, G. max, K. fedtschenkoi, M. domestica, P. granatum, P. trichocarpa, T. cacao, V. vinifera). Before the application of OrthoMCL, BLASTP was used to find similar matches from different species with an E-value cutoff of 1e–05. The composition of the OrthoMCL clusters was used to calculate the total number of gene families.

Orthogroups that were present in a single copy in all species analyzed were selected and aligned using MAFFT v7.31058. Each gene tree was constructed by using RAxML v8.2.459 with the GTRGAMMA model. To construct the species phylogenetic tree, a coalescent-based method in ASTRAL v4.10.460 with 100 replicates of multilocus bootstrapping61 was used.

The divergence time between A. carambola and other species was estimated using MCMCTREE59 with the default parameters. The expansion and contraction of gene family numbers were predicted using CAFÉ25 by employing the phylogenetic tree and gene family statistics.

To further perform the phylogenetic analysis of the key enzyme GalDH in the vitamin C pathway, we annotated orthologous genes from six other plant species (A. thaliana, C. papaya, C. sinensis, P. trichocarp, V. vinifera, S. lycopersicum) using BLASTP with an E-value cutoff of 1e–05 to align coding sequences against the KEGG database. In total, 55 orthologous genes were used to generate a phylogenetic tree via the maximum likelihood (ML) method in RAxML v 8.2.459, and 20 runs were included to identify an optimal tree using the GTRGAMMA substitution model and 100 nonparametric bootstrap replicates.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2019YFC1711000), the Shenzhen Municipal Government of China (grants JCYJ20170817145512476 and JCYJ20160510141910129), the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Genome Read and Write (grant 2017B030301011), and the NMPA Key Laboratory for the Rapid Testing Technology of Drugs.

Author contributions

R.-c.M., J.L., J.-m.Z., T.Y., Y.-x.Z. and W.-x.M. collected the samples; W.-x.M. and S.K.S. conceived and conducted the experiments; Y.-n.F. and T.Y. analyzed the results; Y.-n.F. and S.K.S. wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA: https://db.cngb.org/cnsa). The raw sequencing data are under ID CNR0066625, and assembly data are under ID CNA0002506. All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Yannan Fan, Sunil Kumar Sahu

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41438-020-0306-4).

References

- 1.Muthu N, Lee SY, Phua KK, Bhore SJ. Nutritional, medicinal and toxicological attributes of star-fruits (Averrhoa carambola L.): a review. Bioinformation. 2016;12:420–424. doi: 10.6026/97320630012420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoo H, et al. A review on underutilized tropical fruits in Malaysia. Guangxi Agric. Sci. 2010;41:698–702. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray, P. K. Breeding Tropical and Subtropical Fruits, XVI. 338 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2002).

- 4.Wu S-C, Wu S-H, Chau C-F. Improvement of the hypocholesterolemic activities of two common fruit fibers by micronization processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:5610–5614. doi: 10.1021/jf9010388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabrini DA, et al. Analysis of the potential topical anti-inflammatory activity of Averrhoa carambola L. in mice. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011;2011:908059–908059. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neq026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shui G, Leong LP. Analysis of polyphenolic antioxidants in star fruit using liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1022:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Annegowda HV, Bhat R, Min-Tze L, Karim AA, Mansor SM. Influence of sonication treatments and extraction solvents on the phenolics and antioxidants in star fruits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012;49:510–514. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cazarolli LH, et al. Anti-hyperglycemic action of apigenin-6-C-β-fucopyranoside from Averrhoa carambola. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:1176–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suluvoy JK, Sakthivel KM, Guruvayoorappan C, Berlin Grace VM. Protective effect of Averrhoa bilimbi L. fruit extract on ulcerative colitis in wistar rats via regulation of inflammatory mediators and cytokines. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;91:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei X, et al. Protective effects of 2-dodecyl-6-methoxycyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione isolated from Averrhoa carambola L. (Oxalidaceae) roots on neuron apoptosis and memory deficits in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;49:1105–1114. doi: 10.1159/000493289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng S, et al. 10KP: a phylodiverse genome sequencing plan. Gigascience. 2018;7:giy013. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H, et al. Molecular digitization of a botanical garden: high-depth whole genome sequencing of 689 vascular plant species from the Ruili Botanical Garden. GigaScience. 2019;8:1–9. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giz007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisenfeld NI, Kumar V, Shah P, Church DM, Jaffe DB. Direct determination of diploid genome sequences. Genome Res. 2017;27:757–767. doi: 10.1101/gr.214874.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waterhouse RM, et al. BUSCO applications from quality assessments to gene prediction and phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;35:543–548. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasimuddin, M. et al. Efficient Architecture-Aware Acceleration of BWA-MEM for Multicore Systems. IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 314–324 (2019).

- 16.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bairoch A, Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:45–48. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quevillon E, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W116–W120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argout X, et al. The genome of Theobroma cacao. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:101. doi: 10.1038/ng.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swarbreck D, et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): gene structure and function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;36:D1009–D1014. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuskan GA, et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray) Science. 2006;313:1596–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaillon O, et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449:463. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chase MW, et al. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;181:1–20. doi: 10.1111/boj.12385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia X, Xie H, Jiang Y, Wei X. Flavonoids isolated from the fresh sweet fruit of Averrhoa carambola, commonly known as star fruit. Phytochemistry. 2018;153:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moresco HH, Queiroz GS, Pizzolatti MG, Brighente IM. Chemical constituents and evaluation of the toxic and antioxidant activities of Averrhoa carambola leaves. Braz. J. Pharmacogn. 2012;22:319–324. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wheeler GL, Jones MA, Smirnoff N. The biosynthetic pathway of vitamin C in higher plants. Nature. 1998;393:365. doi: 10.1038/30728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laing WA, Wright MA, Cooney J, Bulley SM. The missing step of the l-galactose pathway of ascorbate biosynthesis in plants, an l-galactose guanyltransferase, increases leaf ascorbate content. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9534–9539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurup SB, Mini S. Averrhoa bilimbi fruits attenuate hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, Zhang X, Tian X. Extraction and purification of flavonoids in Carambola. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 2009;40:491–493. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang D, Xie H, Jia X, Wei X. Flavonoid C-glycosides from star fruit and their antioxidant activity. J. Funct. Foods. 2015;16:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.04.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia X, Xie H, Jiang Y, Wei X. Phytochemistry flavonoids isolated from the fresh sweet fruit of Averrhoa carambola, commonly known as star fruit. Phytochem. 2018;153:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moresco HH, Queiroz GS, Pizzolatti MG, Brighente I. Chemical constituents and evaluation of the toxic and antioxidant activities of Averrhoa carambola leaves. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2012;22:319–324. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2011005000217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiwari, K., Masood, M. & Minocha, P. Chemical constituents of Gmelina phillipinensis, Adenocalymna nitida, Allamanda cathartica, Averrhoa carambola and Maba buxifolia. J. Indian Chem. Soc. (1979).

- 36.Gunasegaran R. Flavonoids and anthocyanins of three Oxalidaceae. Fitoterapia. 1992;63:89–90. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahu, S. K., Thangaraj, M. & Kathiresan, K. DNA extraction protocol for plants with high levels of secondary metabolites and polysaccharides without using liquid nitrogen and phenol. ISRN Mol. Biol.2012, 1–6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.10X Genomics. https://www.10xgenomics.com (2017).

- 39.Marçais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo R, et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience. 2012;1:18. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tarailo‐Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform.25, 4.10.11–14.10.14 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Jurka J, et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:i351–i358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W265–W268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell, M. S., Holt, C., Moore, B. & Yandell, M. Genome annotation and curation using MAKER and MAKER‐P. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform.48, 4.11.11–14.11.39 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Kent WJ. BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R. GeneWise and genomewise. Genome Res. 2004;14:988–995. doi: 10.1101/gr.1865504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanke M, Schöffmann O, Morgenstern B, Waack S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinform. 2006;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lomsadze A, Ter-Hovhannisyan V, Chernoff YO, Borodovsky M. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6494–6506. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1335–1337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nawrocki EP, et al. Rfam 12.0: updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;43:D130–D137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zwaenepoel A, Van de Peer Y. wgd—simple command line tools for the analysis of ancient whole-genome duplications. Bioinformatics. 2018;35:2153–2155. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Proost S, et al. i-ADHoRe 3.0—fast and sensitive detection of genomic homology in extremely large data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:e11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mirarab S, et al. ASTRAL: genome-scale coalescent-based species tree estimation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:i541–i548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seo T-K. Calculating bootstrap probabilities of phylogeny using multilocus sequence data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:960–971. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA: https://db.cngb.org/cnsa). The raw sequencing data are under ID CNR0066625, and assembly data are under ID CNA0002506. All other data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.