On 11 March 2020, The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID‐19 a pandemic and began announcing global health recommendations to decrease morbidity and mortality. Serendipitously, our team of health and social scientists captured data related to the diffusion of information about COVID‐19 and breastfeeding and prompted this commentary.

Since December 2019, we have been capturing Twitter data and employing social network analyses to examine the diffusion of pseudoscience and misinformation related to breastfeeding. We focused on breastfeeding as the death of 800,000 infants and 20,000 mothers may be prevented annually with universal, exclusive and sustained breastfeeding (Bode, Raman, Murch, Rollinc, & Gordon, 2020; Victora et al., 2016). Recently, we were reviewing our latest capture and realized we had data on COVID‐19 and breastfeeding, and as such, this commentary relates to our “just in time” findings that may be of importance to the many agencies (governmental and non‐governmental) and research groups who focus on diffusing information related to the pandemic.

The spread of health (mis)information particularly in times of crisis may cost human lives (Caulfield et al., 2019). As such, it becomes even more critical to track and evaluate the extent to which messages from health authorities are accurately diffused. However, in‐depth tracking is challenging at scale especially in online dynamic spaces. On Twitter alone, one of the largest social media platforms worldwide, estimates indicate that more than 410 million tweets with #Covid19 or #Coronavirus have been shared to date. Collecting, analysing and reporting data of this breadth and depth are difficult given both the amount of data and the dynamic evolution of data over time. Rather than present the totality of data, we present findings about the diffusion of information related to “breastfeeding and COVID‐19” that were unintentionally captured.

We have been harvesting all tweets and general user profile information from common breastfeeding hashtags (e.g., #breastfeeding, #normalizebreastfeeding and #breastmilk) resulting in a large dataset from which we now have two papers under review. The hashtags were a starting point that made sure we were locating our work in the correct research “location.” In the midst of that work, on 16 March, the WHO released its interim guidelines for breastfeeding during the COVID‐19 outbreak (World Health Organization (March 16, 2020), followed by UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative on 17 March (UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative, 2020). As such, we ended up quite by accident capturing all tweets related to breastfeeding and #COVID‐19 and #coronavirus. We conducted a social network analysis including several network metrics, structural communities (users who interact more frequently among each other than others) and key diffusers (top 5% of users with highest degree centrality), and then categorized users and tweets using inductive qualitative coding (Daly, 2010; Del Fresno, Daly, & Segado, 2016; Lee, DeCamp, Dredze, Chisolm, & Berger, 2014).

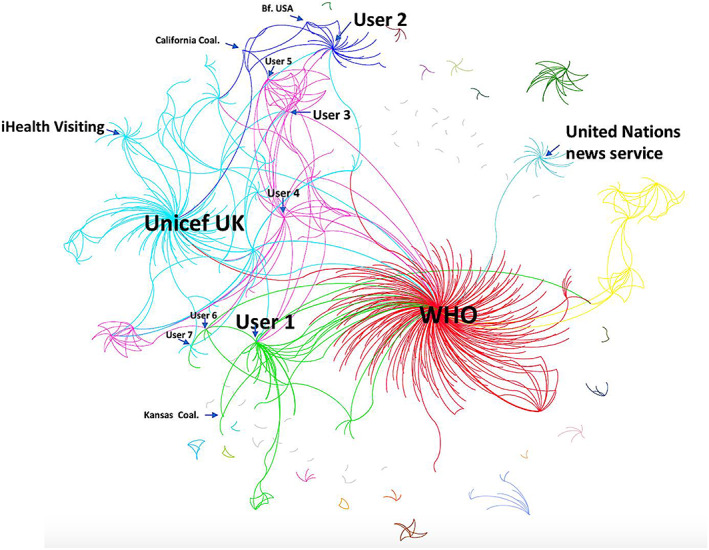

Our findings indicate a “breastfeeding and COVID‐19” social network totaling 756 unique users, 880 tweets and 28 distinct communities (Figure 1 ; Table 1). While communities do have their own patterns of interactions, it is the WHO along with seven other professional users that act as key diffusers of information (UNICEF UK baby Friendly Initiative, UN News Service, Institute of Health Visiting in the UK, two academics involved in public health policy with leadership positions, and two international board certified lactation consultants [IBCLC]). We also identified network brokers who connected otherwise disconnected communities and bridged messages across the network. These included a non‐governmental agency (Breastfeeding USA), professional coalitions (California Breastfeeding Coalition and Kansas Breastfeeding Coalition), and professionals (two academics in nursing and midwifery, one academic in public health, one medical anthropologist, and an IBCLC).

FIGURE 1.

“Breastfeeding and COVID‐19” overall social network on Twitter. Each dot represents a unique user that tweeted to the network until 27 March 2019. The lines between the dots reflect exchanged tweets (tweets, retweets or mentions). The size of selected user names reflect central diffusers and brokers based their overall degree centrality and betweenness, respectively. The colour of the lines represent communities based on interaction behaviour in the network. Map represents n = 756 users, 880 tweets and 28 communities. Key diffusers: WHO, World Health Organization; Unicef UK, UNICEF UKbaby Friendly Initiative; United Nations news service; ihealth Visiting, Institute of Health Visiting in the United Kingdom, users 2 and 3, two academic researchers involved in public health policy with leadership positions; users 1 and 4, two international board certified lactation consultants (IBCLC). Key brokers: Bf USA, non‐governmental agency Breastfeeding USA; California Coal., Breastfeeding Coalition; Kansas Coal., Kansas Breastfeeding Coalition; users 6 and 7, academic researchers in nursing and midwifery, user 3, one academic researcher in public health policy and leadership; user 5, a medical anthropologist, user 1, an IBCLC

TABLE 1.

Description of users in the “Breastfeeding and COVID‐19” overall social network on Twitter

| Number of users | Number of users | |

|---|---|---|

| Professionals | 378 | 51.2 |

| Health care practitioners | 173 | 23.4 |

| Non‐governmental agencies | 95 | 12.9 |

| Researchers | 58 | 7.8 |

| Governmental agencies | 27 | 3.7 |

| Researchers and practitioners | 15 | 2.0 |

| News agencies | 10 | 1.4 |

| Interested citizens | 340 | 46 |

| Companies | 21 | 2.8 |

Note: n = 739 users. The accounts of the 17 users could not be verified.

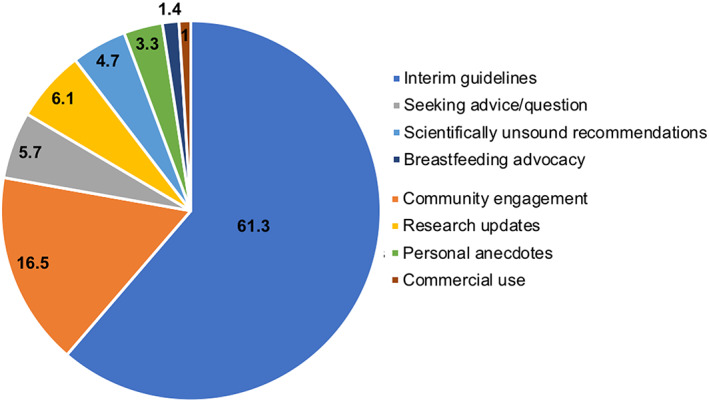

The positive side of the findings, and counter to the typical narrative around social media, is that the vast majority of tweets reflected current scientific guidance, updates from researchers about ongoing COVID‐19 studies, as well as community engagement and breastfeeding advocacy to support clinicians and families (Figure 2 , Table 2). However, despite diffusion of accurate information, we did identify 6% of the tweets that contained scientifically unfounded recommendations and tweets for commercial use (e.g., promoting brands of breast pumps and feeding bottles).

FIGURE 2.

Content analysis by percentage of 880 total tweets

TABLE 2.

Few examples of evidence‐informed advice and community engagement around breastfeeding shared on Twitter

| “When severe illness prevents a mother with #COVID19 or other complications from caring for her infant or continuing direct #breastfeeding, they should be encouraged & supported to express milk & safely provide breastmilk, with appropriate infection prevention & control measures.” Tweeted by (username, World Health Organization (WHO), account of: WHO) |

|

“Mothers with #COVID19 symptoms who are #breastfeeding or practising skin‐to‐skin contact should practise: • Respiratory hygiene, incl. during feeding • Hand hygiene before & after contact with a child • Routinely clean & disinfect surfaces which they have been in contact with” Tweeted by (username, World Health Organization (WHO), account of: WHO) |

| “Unicef UK Baby Friendly Initiative statement on infant feeding on neonatal units during the #Covid19 outbreak & guidance on how to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding for all sick and preterm babies either in transitional or neonatal care: https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/infant‐feeding‐on‐neonatal‐units‐during‐the‐covid‐19‐outbreak/” Tweeted by (usernameBaby Friendly UK, account of, UNICEF UK baby Friendly Initiative) |

| “Updated 18th March 2020 Unicef UK Baby Friendly Initiative Statement on Infant Feeding during the COVID‐19 outbreak ‐ information on how to protect support and promote #breastfeeding and guidance on #formula feeding @1stepsnutrition: https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/infant‐feeding‐during‐the‐covid‐19‐outbreak/” Tweeted by (usernameBaby Friendly UK, account of, UNICEF UK baby Friendly Initiative) |

| During this worldwide crisis, let us keep in mind that #breastfeeding can save lives. No evidence that mother's should stop breastfeeding if they have #COVID19. (Tweet was paraphrased to protect individual's identity) |

| “We are continuing to offer #breastfeeding support remotely during the Covid‐19 situation and can help answer questions, offer support and provide a listening ear. More info: https://breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/coronavirus/ #BfNSupport” Tweeted by (username: BfN, account of The Breastfeeding Network) |

In these difficult times when anecdotal health recommendations and misinformation may overwhelm the health care system and cause large numbers of preventable illness and death, it is heartening to learn that there is evidence of the flow of accurate information that supports the health of mothers and infants. However, we must stand vigilant in our information battle with COVID‐19 and continue to leverage analytical approaches that help identify if and when guidelines are tampered with before the problem and consequences become too big to fix.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

SM and AJD designed the original study. SM, AJD and DFM performed the research. SM and DFM analysed the data. SM, AJD and LB interpreted the findings. All authors wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethics approval was not required as the study only uses publicly available data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Family Larsson‐Rosenquist Foundation.

REFERENCES

- Bode, L. , Raman, A. S. , Murch, S. H. , Rollinc, N. C. , & Gordon, J. I. (2020). Understanding the mother‐breastmilk‐infant “triad”. Science, 367(6482), 1070–1072. 10.1126/science.aaw6147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, T. , Marcon, A. R. , Murdoch, B. , Brown, J. M. , Perrault, S. T. , Jarry, J. , & Hyde‐Lay, R. (2019). Health misinformation and the power of narrative messaging in the public sphere. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, 2(2), 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, A. J. (2010). Social network theory and educational change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Del Fresno, M. , Daly, A. J. , & Segado, S.‐C. S. (2016). Identifying the new influencers in the Internet era: Social media and social network analysis. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 153, 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. L. , DeCamp, M. , Dredze, M. , Chisolm, M. S. , & Berger, Z. D. (2014). What are health‐related users tweeting? A qualitative content analysis of health‐related users and their messages on twitter. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(10), e237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative . (March 17, 2020). Statement on infant feeding during the Covid‐19 outbreak. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/about/statements/

- Victora, C. , Bahl, R. , Barros, A. , França, G. , Horton, S. , Krasevec, J. , … Rollins, N. C. (2016). Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet, 30, 475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (March 16, 2020). Breastfeeding advice during Covid‐19 outbreak. Retrieved from http://www.emro.who.int/nutrition/nutrition-infocus/breastfeeding-advice-during-covid-19-outbreak.html