To the Editor:

Viral acute respiratory infections (ARI) are associated with thrombotic events, 1 and the pathophysiology of this association is multifactorial. 2 Although most ARIs are mild, subpopulation of patients can progress to severe disease with excessive proinflammatory response, and downstream uncontrolled cytokine storm being partially implicated for this severe manifestation. 3 As there is extensive crosstalk between inflammation and coagulation, it is likely the prothrombotic mechanisms in viral ARI could be further exacerbated in patients suffering from severe ARI. The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is an evolving pandemic. Approximately one‐fifth of the infected individuals develops severe to critical disease 4 requiring intensive care support. These critically ill patients often exhibit marked elevation of proinflammatory cytokines and C‐reactive protein (CRP) 4 consistent with hyperinflammation. Nonetheless, the effects of COVID‐19 infection on haemostatic functions remain unknown at the present moment.

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)‐based clot waveform analysis (CWA) is a form of global haemostatic assay in which lower and higher CWA parameters are associated with bleeding and hypercoagulability respectively. 5 We postulated COVID‐19 patients requiring intensive care unit (ICU) support would exhibit haemostatic disturbances and interrogated their aPTT‐based CWA parameters as surrogates of their haemostatic functions.

In February 2020, three COVID‐19 patients were admitted to ICU of Singapore General Hospital and Sengkang General Hospital, Singapore and we examined their clinical and hematological data. The aPTT tests were performed as part of their routine clinical management. The associated CWA data; maximum velocity (min1), maximum acceleration (min2) and maximum deceleration (max2) were retrieved from the CS2100i and CS2500 automated coagulation analysers (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) from the respective hospitals. Dade Actin FSL (Siemens Healthcare, Marburg, Germany) reagent was used.

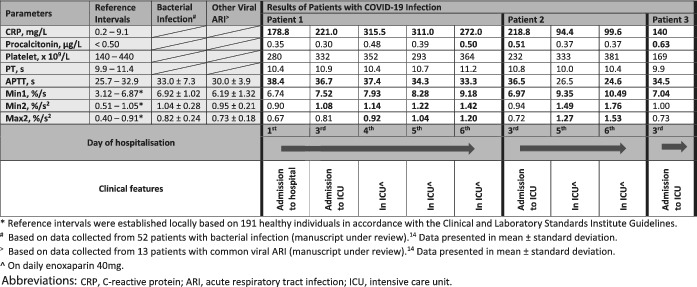

All three COVID‐19 patients in the ICU at the time were included. All three patients did not have any pre‐existing malignancy, bleeding or thrombotic conditions and were not on any antithrombotic drugs on admission. Two patients (ages 39 and 64) had no pre‐existing conditions and one patient (age 54) had hypertension and hyperlipidemia. None had other superimposed infection or overt disseminated intravascular coagulation by the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria. Their clinical and laboratory features are summarized in Table 1. Only patient 2 had a single D‐dimer value of 0.64 mg/L fibrinogen equivalent unit (FEU) (normal range: 0.19‐0.55 mg/L FEU) performed upon the ICU admission. Whilst aPTT showed mild prolongation in most of the results and no biphasic waveform was noted, analyses of their CWA revealed interesting findings. All three patients had elevated min1 when their clinical conditions deteriorated to the point of requiring ICU support. Furthermore, all their CWA parameters became markedly raised as their ICU stay progressed. Serial CWA data for patient 1 shed some interesting light on how the overall dynamic haemostatic status changed with clinical deterioration; from fairly normal CWA on initial hospitalization to having markedly raised parameters in ICU. This suggested a positive association between the rise in CWA parameters and the worsening severity of COVID‐19 infection.

TABLE 1.

Laboratory results and clinical features of COVID‐19 infected patients in reference to the normal intervals of clot waveform analysis (CWA) parameters and CWA data of patients with bacterial and other viral acute respiratory tract infections.

|

|

On day 1 of hospitalization, although patient 1 had CWA parameters within normal intervals, COVID‐19 infection resulted in some interesting differences in CWA, compared to CWA findings caused by other infections. Compared with other common viral ARI and bacterial infection, 7 min1 in COVID‐19 infection was higher than other ARIs and tracked closer to bacterial infection. However, min2 and max2 were lower than the other infections. This suggests that COVID‐19 infection causes dissimilar haemostatic derangement, even in non‐critical cases, compared to other ARI. The higher min1 value could possibly suggest an overall elevated prothrombotic state in COVID‐19 infection given our previous finding that min1, in comparison to min2 and max2, is more strongly associated with thrombotic events. 5

Consistent with published reports, 4 all the patients expressed high CRP levels even on initial assessment during hospitalization, while procalcitonin remained unremarkable (data not shown). We did not observe a definitive pattern of association between CRP and ICU admission ‐ patient 3 had a CRP upon ICU admission that was lower than that of patient 1 upon initial hospitalization. In contrast, as these patients’ clinical conditions turned critical, min1 seemed to be the first CWA parameter to rise, with all three patients exhibiting raised min1 upon ICU admission. This raises the exciting possibility that high min1 may be a useful biomarker to predict severity in COVID‐19 infected patients, but further study is needed.

From the second day of ICU admission onward, all the CWA parameters became markedly elevated for at least the ensuing 4 days of ICU stay. Many of the levels were at least as high as what we noted in acute venous thromboembolism, which had an odds ratio of four or greater for thrombotic events. 5 Of note, although none of our cases developed thrombosis, our patients’ CWA parameters remained remarkably high despite the use of thromboprophylaxis during their ICU stay. It is possible that CWA and other thrombin generation assays might not be sensitive enough to detect the haemostatic changes caused by the standard prophylactic dose of low molecular weight heparin. All three patients recovered from COVID‐19 infection.

Thatour findings of markedly raised CWA parameters in critically ill infected cases are possibly consistent with hypercoagulability is not unexpected. Such patients exhibit hyperinflammation and cytokine overdrive, and extensive crosstalk is known to exist in the cytokines, the inflammatory system, and coagulation. 6 Critically ill COVID‐19 patients have been shown to have increased proinflammatory cytokines including IL‐2 and TNF‐α, 4 and these factors could upregulate the coagulation system. 6 We speculate that this could partially account for the CWA changes observed.

Although our findings are limited by the relatively few patients and data points and by the lack of other correlation studies with other coagulation assays, we believe there are still valuable points to take away. Many of the specialized and research haemostatic assays cannot be safely and easily performed on samples collected from COVID‐19 patients in view of laboratory biosafety concerns. As COVID‐19 infection is spreading relentlessly worldwide, there is an urgent need for rapid and readily accessible biomarkers that can aid clinical stratification and management. So, CWA represents a simple, automated and rapid test, which fulfills these biosafety criteria. Whenever an aPTT is performed, an aPTT waveform is generated automatically by commonly used optical analysers worldwide.

In conclusion, the rise of CWA parameters precedes and coincides with ICU admission and warrant further study to confirm its utility in the routine management of COVID‐19 patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study received no specific funding from any public or commercial agency.

REFERENCES

- 1. Smeeth L, Cook C, Thomas S, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Vallance P. Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after acute infection in a community setting. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1075‐1079. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68474-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. VAN WISSEN M, KELLER TT, VAN GORP ECM, et al. Acute respiratory tract infection leads to procoagulant changes in human subjects. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(7):1432‐1434. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04340.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu Q, Zhou YH, Yang ZQ. The cytokine storm of severe influenza and development of immunomodulatory therapy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13(1):3‐10. 10.1038/cmi.2015.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tan CW, Cheen MHH, Wong WH, et al. Elevated activated partial thromboplastin time‐based clot waveform analysis markers have strong positive association with acute venous thromboembolism. Biochem Med. 2019;29(2):020710. 10.11613/BM.2019.020710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foley JH, Conway EM. Cross Talk Pathways between Coagulation and Inflammation. Circ Res. 2016;118(9):1392‐1408. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence Ng CK, Tan CW, Cheen HHM, Wong WH, Chu MHY, Lim SS, Yeo GDD, Morvil G, Joo Ng H. APTT‐based clot waveform analysis in various infections. EHA Library. 2018;215813:PS1530. [Google Scholar]