Abstract

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection has recently spread globally and is now a pandemic. As a result, university hospitals have had to take unprecedented measures of containment, including asking nonessential staff to stay at home. Medical students practicing in the surgical departments find themselves idle, as nonurgent surgical activity has been canceled, until further notice. Likewise, universities are closed and medical training for students is likely to suffer if teachers do not implement urgent measures to provide continuing education. Thus, we sought to set up a daily medical education procedure for surgical students confined to their homes. We report a simple and free teaching method intended to compensate for the disappearance of daily lessons performed in the surgery department using the Google Hangouts application. This video conference method can be applied to clinical as well as anatomy lessons.

Keywords: anatomical learning, anatomy, COVID‐19 pandemic, medical education

1. INTRODUCTION

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection has recently spread global and is now a pandemic (Bedford et al., 2020). As a result, the university public hospitals have had to take unprecedented measures of containment, including asking nonessential medical staff to stay at home. In fact, medical students practicing in the surgical departments find themselves idle, as nonurgent surgical activity has been canceled, until further notice. Likewise, universities are closed and medical training for students is likely to suffer if teachers do not implement urgent measures to provide continuing education. Thus, we sought to set up a daily medical education procedure for surgical students confined to their homes.

2. SIMPLE VIDEOCONFERENCE SOLUTION FOR CONFINED STUDENTS

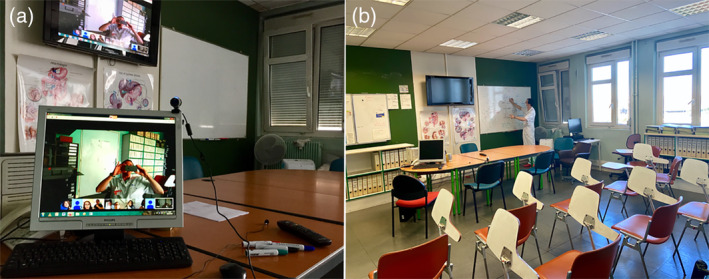

The purpose of this method is to compensate for the withdrawal of clinical lessons performed daily on the board in the surgery department. This videoconference method can be applied to clinical lessons as well as anatomy lessons. We used the Google Hangouts app, which is available to all at no cost, and easily found in the application list for Gmail users. A webcam and a microphone are required on the workstation. A working group is then created using their email addresses. Similar to regular lessons, an appointment is given to students, allowing them to connect at the right time (Figure 1a). Up to 10 students can access the live lesson at the same time (Figure 1b). They can see and hear the teacher and also ask questions that are audible to the whole group. There is no time limitation.

FIGURE 1.

(a) The teacher is visible in the center of the screen and the confined students connected to Google Hangouts app, at the bottom of the screen. (b) The empty classroom is shown; the teacher gives a lesson on the whiteboard (about colonic diverticulitis). The webcam and microphone are located at a good distance [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3. RETHINKING ANATOMICAL AND MEDICAL EDUCATION

In the recent past, anatomical and medical education have been mainly based on traditional schooling, with lecturing and blackboard chalk drawings, the predominant teaching method with students being primarily passive (the “little frozen,” as French philosopher Michel Serres called them). Due to the easy access to online knowledge, high absenteeism has become one of the main problems facing medical schools. In addition, the costs of human tissue and ethical issues are significant burdens that are not easily overcome and make practical training with cadaveric courses an unavailable option for many institutions. Finally, environmental constraints are changing and, as a result, multiple reasons motivate students to stay at home.

Once the COVID pandemic has been brought under control, it will be necessary to continue to rethink medical teaching, by implementing different teaching techniques complementary to conventional face‐to‐face education. Blended learning, defined as the combination of conventional face‐to‐face learning and asynchronous or synchronous e‐learning, has grown quickly and is now extensively used in medical education (Liu et al., 2016; Vodovar et al., 2020). In the same way, the flipped classroom approach to teaching has been increasingly used in scholarly medical education. In such classroom applications, students are first exposed to content via online resources. Subsequent face‐to‐face class time can then be devoted to student‐centered activities that enhance active learning (Ramnanan et al., 2017).

Blended learning has been shown to be effective, complementary to traditional education for teaching human anatomy, as well (Khalil et al., 2018). Anatomical education has been greatly enriched by recent online accessible technological improvements in simulation and material sciences, namely, 3D printing (Clifton et al., 2020), virtual interactive anatomy dissection table, and 3D reconstruction models (Moszkowicz et al., 2011).

4. CONCLUSIONS

As the behavior of students and environmental constraints evolve, the priority that must be placed on educational research is self‐evident. Usable in confinement, blended‐learning methods and modern educational tools develop and can be a response to student nonattendance to lectures.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Moszkowicz D, Duboc H, Dubertret C, Roux D, Bretagnol F. Daily medical education for confined students during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A simple videoconference solution. Clin Anat. 2020;33:927–928. 10.1002/ca.23601

REFERENCES

- Bedford, J. , Enria, D. , Giesecke, J. , Heymann, D. L. , Ihekweazu, C. , Kobinger, G. , … for theWHO Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Infectious Hazards . (2020). COVID‐19: Towards controlling of a pandemic. The Lancet, 395(10229), 1015–1018. pii: S0140‐6736(20)30673‐5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30673-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, W. , Damon, A. , Nottmeier, E. , & Pichelmann, M. (2020). The importance of teaching clinical anatomy in surgical skills education: Spare the patient, use a Sim! Clinical Anatomy, 33(1), 124–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, M. K. , Abdel Meguid, E. M. , & Elkhider, I. A. (2018). Teaching of anatomical sciences: A blended learning approach. Clinical Anatomy, 31(3), 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Peng W, Zhang F, Hu R, Li Y, Yan W. 2016. The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 4;18(1):e2. 10.2196/jmir.4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moszkowicz, D. , Alsaid, B. , Bessede, T. , Penna, C. , Benoit, G. , & Peschaud, F. (2011). Female pelvic autonomic neuroanatomy based on conventional macroscopic and computer‐assisted anatomic dissections. Surgical and Radiological Anatomy, 33(5), 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramnanan, C. J. , & Pound, L. D. (2017). Advances in medical education and practice: Student perceptions of the flipped classroom. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 13(8), 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovar, D. , Ricard, J. D. , Zafrani, L. , Weiss, E. , Desrentes, E. , & Roux, D. (2020). Assessment of a newly‐implemented blended teaching of intensive care and emergency medicine at Paris‐Diderot University. La Revue de Médecine Interne pii: S0248‐8663(20)30009‐6. 10.1016/j.revmed.2019.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]