Abstract

Head and neck examinations are commonly performed by all physicians. In the era of the COVID‐19 pandemic caused by the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus, which has a high viral load in the upper airways, these examinations and procedures of the upper aerodigestive tract must be approached with caution. Based on experience and evidence from SARS‐CoV‐1 and early experience with SARS‐CoV‐2, we provide our perspective and guidance on mitigating transmission risk during head and neck examination, upper airway endoscopy, and head and neck mucosal surgery including tracheostomy.

Keywords: COVID‐19, head and neck examination, pandemic, practical guide

On 27 March 2020, the Center for Disease Control reported that 85 356 individuals in the United States were infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2)—exceeding, for the first time, the number of cases in Wuhan, China, where the pandemic began in November 2019. US federal, state, and local agencies are facing an unprecedented public health emergency. The scale of the pandemic has never been seen in United States; the way forward uncertain.

In 2003, the Hong Kong SAR (HK) health care system was thrust into a similar crisis, responding to an outbreak of SARS coronavirus 1 (SARS‐CoV‐1), which developed in Guangdong Province, China, in late 2002. Lessons from how HK physicians adapted their practices to this new disease may hold important lessons for the many countries now facing the pandemic. 1

Based on experience and evidence from SARS‐CoV‐1 and early experience with SARS‐CoV‐2, we provide our perspective and guidance on mitigating transmission risk during head and neck examination, upper airway endoscopy, and head and neck mucosal surgery including tracheostomy. We set out the following recommendations that every physician performing head and neck examination should consider. The goal is to protect health care workers (HCW), caregivers, patients, and the community at large in this personal protective equipment (PPE) limited environment, while conforming to their local guidelines.

Early on in the 2003 SARS epidemic, the risk of nosocomial spread of infection to HCW posed a critical challenge. At the Prince of Wales Hospital, HK, a single infected patient caused an outbreak, of which over 50% were HCW, devastating human resources to treat and contain the infection. 2 Seventeen years later, HK was inflicted with SARS‐CoV‐2 late January 2020. A benefit of SARS‐COV‐1 in HK HCW has been the modus operandi since 2003: including wearing surgical masks in hospital wards, wearing gowns and surgical masks in outpatient clinics and scrubs only in the operating room. The resultant individual and institutional appreciation of infection control measures has served HK well in the current pandemic, relative to other countries, with no HCW COVID‐19 nosocomial infections to date. 1

In the 2003 SARS‐CoV‐1 outbreak in HK, an otolaryngologist died after being infected during a routine head and neck examination. In 2020, the first COVID‐19 physician fatality was an otolaryngologist in Wuhan, China. Patients with COVID‐19 caused by SARS‐CoV‐2 can carry high viral load in the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, and throat. 3 The anatomic viral distribution of these SARS‐CoV viruses in the nasopharynx and mucosal airways, coupled with these disquieting cases, indicates that head and neck examinations and procedures must be approached cautiously with thoughtful preparation and protections. HCW who have these exposures are at heightened risk of transmission.

In the outpatient setting, all nonessential clinic visits should be transitioned to virtual “video visits” or postponed. This will reduce the number of patients in the clinic, minimizing patient flow and potential contamination and freeing up valuable medical resources. On 18 March 2020, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the United States released recommendations to postpone all nonessential dental exams and procedures until further notice. 4

Within the clinic, separate gown up and gown down areas must be designated to prevent cross‐contamination. Visual guides and mirrors for self‐visualization in these areas on the steps involved in gowning up and gowning down have, from past experience, proven extremely useful particularly for gowning down, where most HCW self‐contaminate (Figure 1). Another critical area is the bedside examination of patients. Currently, there are no CDC guidelines on respiratory and aerosol‐generating procedures within the scope of the head and neck surgery, but our experience with SARS‐CoV‐1 highlights that these are potentially high‐risk examinations. Therefore, in HK, there is official guidance for Otolaryngology departments to label several common head and neck examination and procedures as having a potential risk of aerosol generation. This designation carries implications on PPE allocations of as seen in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

The red diagram on the left represents the steps in gowning up and the green diagram on the right illustrates the gowning down steps which needs great care. These are readily available in all gown up and gown down areas with a mirror [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 1.

Recommended personal protective equipment for different procedures in an otolaryngology clinic

| Normal head and neck examination | Procedures in the endoscopy room | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible laryngoscopy/nasoendoscopy | Oral and nasal and ear open suction | Change of tracheostomy tube | Endoscopic guided insertion of feeding tube | Change of tracheoesophageal prosthesis | ||

| Hand hygiene | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Surgical mask | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| N95 mask | Yes a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Isolation gown | No | AAMI level 1 | AAMI level 1 | AAMI level 1 | AAMI level 1 | AAMI level 1 |

| Disposable gloves | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Eye protection | Visor/face shield a | Face shield | Face shield | Face shield | Face shield | Face shield |

| Hair cover | Optional | Optional | Optional | Optional | Optional | Optional |

Note: These procedures are usually done in bundle by a single otolaryngology specialist for the most prudent use of appropriate PPEs.

N95 and face shield are only for deep throat examinations (eg, checking of tonsil mass, ulcer at retromolar trigone region) usually done with flexible laryngoscopy in the endoscopy room.

Anesthetic practices vary but local anesthetic is commonly administered via aerosolized spray in the head and neck examination and procedures. This practice has been abandoned in HK since the SARS‐COV‐1 epidemic and must be avoided in the current COVID‐19 environment. Aerosol spray should be replaced by topical local anesthetic on pledgets or dripped via syringe. Table 1 shows guidelines of PPE use within the outpatient clinic with a dedicated endoscopy room, including flexible laryngoscopy—one of the most common procedures performed in head and neck examination. Unless there is gross contamination, there is no need to change the gown, mask, or eye protection between each patient.

For inpatient rounds, all physicians are recommended to wear a surgical mask and scrubs, which are changed daily prior to leaving the hospital. Patient visitors to the hospital should be severely restricted, and visiting hours cut, to minimize people flow and maintain social distancing.

For all operative procedures, intubation represents an aerosol‐generating procedure as first learned during the 2003 SARS‐COV‐1 epidemic. Therefore, during intubation, anyone in the operating room should have appropriate PPE including a fit‐tested N95 mask. This should similarly apply to all open airway procedures such as direct laryngoscopy where they may be a leak during ventilation, tracheostomy, or laryngectomy.

Tracheostomies for patients with known COVID‐19 should be delayed where possible to minimize viral shedding from the patient, as we know from SARS‐COV‐1, delaying the tracheostomy does not negatively impact the patient. Guidance for a safe tracheostomy emerged from the 2003 epidemic. 5 The following should be considered for tracheostomies in the COVID‐19 pandemic:

PPE: Asociation for the advancement of medical instrumentation (AAMI) level 3 or waterproof apron on top of AAMI level I isolation gown, N95 mask, face shield, waterproof cap and disposable shoe covers. Powered air purifying respirators may be needed in cases with high viral load.

Minimize personnel: One intensivist, one surgeon, and one nursing member.

Procedure: Use a negative pressure operating room. The patient should be completely paralyzed and preoxygenated. Stop ventilation before tracheotomy and only resume once tracheostomy tube balloon cuff is inflated

Postprocedure: Gown down safely and shower.

Ideally, the procedure should be done in a negative pressure operating room with senior personnel and not used as a training procedure. Cautery use should be limited as this can produce small particles that may act as a vehicle for the virus. 5 Again, gowning down following the procedure is of utmost importance and is often overlooked. Dry runs prior to the actual procedure may also help reduce errors and prevent the contamination of HCW.

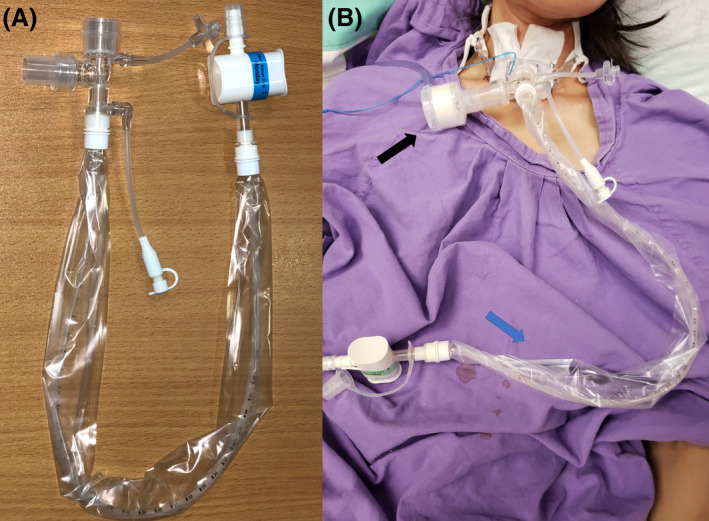

For patients with a tracheostomy, they should all be covered with a closed system (Figure 2) identical to a patient who is connected to a mechanical ventilator to minimize the aerosol generated that could cross‐contaminate the surrounding patients and HCW, given the suction requirements of these patients. 6 Humidified tracheostomy collars and nebulized therapies must be avoided. All bedside procedures should be performed in a separate treatment room away from patient cubicles with all HCW wearing PPE. The requirements for PPE will be the same as in the outpatient clinic.

FIGURE 2.

A, The closed suction kit used with a tracheostomy on the open ward. B, The black arrow points to the heat moisture exchange and the blue arrow to the closed suction kit [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In summary, with the use of these broad guidelines that reduce the number of procedures and patients seen, coupled with an appreciation that the head and neck examination cannot be taken lightly in the current pandemic, the risk of exposure and contamination in clinics of patients, HCW, and in particular, physicians performing a head and neck examination should be reduced.

Chan JYK, Tsang RKY, Yeung KW, et al. There is no routine head and neck exam during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Head & Neck. 2020;42:1235–1239. 10.1002/hed.26168

Raymond K. Y. Tsang is considered as the co‐first author.

Contributor Information

Jason Y. K. Chan, Email: jasonchan@ent.cuhk.edu.hk.

F. Christopher Holsinger, Email: holsinger@stanford.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gawande A. Keeping the Coronavirus from Infecting Health‐Care Workers 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/keeping-the-coronavirus-from-infecting-health-care-workers. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- 2. Cheng VC, Chan JF, To KK, Yuen KY. Clinical management and infection control of SARS: lessons learned. Antiviral Res. 2013;100:407‐419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967‐1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CMS Adult Elective Surgery and Procedures Recommendations: Limit all non‐essential planned surgeries and procedures, including dental, until further notice 2020. Anonymous. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/31820-cms-adult-elective-surgery-and-procedures-recommendations.pdf). Accessed March 20, 2020.

- 5. Wei WI, Tuen HH, Ng RW, Lam LK. Safe tracheostomy for patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1777‐1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan JYK, Lam W. Practical aspects of otolaryngologic clinical services during the 2019 novel coronavirus epidemic: an experience in Hong Kong. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020. 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]