Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused significant shifts in patient care including a steep decline in ambulatory visits and a marked increase in the use of telemedicine. Infantile hemangiomas (IH) can require urgent evaluation and risk stratification to determine which infants need treatment and which can be managed with continued observation. For those requiring treatment, prompt initiation decreases morbidity and improves long‐term outcomes. The Hemangioma Investigator Group has created consensus recommendations for management of IH via telemedicine. FDA/EMA‐approved monitoring guidelines, clinical practice guidelines, and relevant, up‐to‐date publications regarding initiation and monitoring of beta‐blocker therapy were used to inform the recommendations. Clinical decision‐making guidelines about when telehealth is an appropriate alternative to in‐office visits, including medication initiation, dosage changes, and ongoing evaluation, are included. The importance of communication with caregivers in the context of telemedicine is discussed, and online resources for both hemangioma education and propranolol therapy are provided.

Keywords: health care delivery, hemangiomas/vascular tumors, therapy‐systemic

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic has drastically altered health care delivery including widespread reductions in ambulatory visits to minimize exposure to and transmission of COVID‐19 resulting in unprecedented adoption of virtual care via telemedicine platforms. In light of these significant shifts in patient care, the Hemangioma Investigator Group (HIG) met with the goal of creating consensus recommendations to provide timely care for infants with infantile hemangioma (IH) via telehealth. The use of beta‐blockers in the treatment of IH has revolutionized care, and recent American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines (CPG) emphasize that early therapeutic intervention is critical for complicated IH to prevent medical complications or permanent disfigurement. 1 In this statement, we review FDA/EMA‐approved monitoring guidelines, information derived from several clinical practice guidelines, and other publications regarding initiation and monitoring of beta‐blocker therapy, including newly published information which could help inform modification of these practices. We give recommendations to help guide decisions about when telehealth may be an alternative to in‐office visits, including initiation, dosage changes, and continued evaluation for those patients requiring treatment. We also provide tools for patient communication in context of telemedicine. While these recommendations were prompted by the COVID‐19 pandemic, we recognize that they might be relevant in analogous settings where there is a disruption of the normal delivery of medical care and potentially in settings with lack of access to practitioners with expertise in IH management.

2. METHODS

The Hemangioma Investigator Group (HIG) met via videoconferencing on March 22, 2020, and subdivided members into 3 groups: one to work on the introduction and discussion, one to create a table of inclusion and exclusion criteria for telemedicine use of beta‐blockers, and one to curate available patient‐education materials for practitioners and parents. Through an iterative process of review of these 3 domains, we were able to achieve unanimous consensus regarding the content of these recommendations.

2.1. Risk stratification and timing of therapeutic intervention, when needed

The most rapid IH growth occurs between 1 and 3 months of age, and there is a “window of opportunity” to treat problematic IHs in order to prevent morbidities. Telemedicine has a critical role to play in facilitating early evaluation and risk stratification. In areas where access to specialists has long been challenging, telemedicine triage has the potential to improve care for high‐risk IH. Early consultation ideally by 1 month of age or as soon as high‐risk features are recognized is warranted. Table 1, from the AAP CPG, delineates risk categories of IH and potential associated morbidities.

TABLE 1.

Risk level of IHs of varying types

| Risk level | Clinical examples and reason(s) for concern |

|---|---|

| Highest |

|

| High |

|

| Intermediate |

|

| Low |

|

(Reprinted with permission from Ref. 1).

2.2. Potential risks associated with beta‐blocker treatment

Oral beta‐blockers are the gold standard when systemic treatment is indicated for IH and propranolol solution is the only FDA/EMA‐approved treatment. Methods for initiation of oral propranolol have evolved over time. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Consensus recommendations prior to the FDA/EMA approval in 2014 included the following 10 : (a) screening for contraindications to propranolol, (b) performing or obtaining documentation of, a recent normal cardiovascular and pulmonary history and examination, (c) obtaining key historical data including poor feeding, dyspnea, tachypnea, diaphoresis, wheezing, heart murmur, or family history of heart block or arrhythmia, and (d) prolonged in‐office monitoring. The FDA/EMA‐approved administration monitoring recommendations include in‐office heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP) monitoring for 2 hours after the first dose of propranolol or for increasing the dose (>0.5 mg/kg/d) for infants 5 weeks of adjusted gestational age or older. 10 , 11 More recent consensus statements 1 , 12 , 13 , 14 vary in specific recommendations for propranolol initiation. Both Australian and British guidelines 13 , 14 recommend full‐term healthy infants without comorbidities may undergo outpatient initiation without in‐office monitoring with initial doses of 1 mg/kg/d. 13 , 14 Both state that a thorough medical history and clinical examination including HR are prerequisites to initiation of systemic therapy. A recent study by Puttgen et al 15 of 783 patients with in‐office monitoring during medication initiation found no symptomatic bradycardia or hypotension occurred during the in‐office monitoring and minimal, clinically insignificant decrease in HR (mean decrease of 8 to 9 beats per minute). Many practitioners have moved away from in‐office monitoring for those infants of gestationally corrected age of 5 weeks or older with normal birthweight unless other risk factors exist.

While rare, hypoglycemia, seen primarily with intercurrent illness or decreased feeding, is a serious potentially life‐threatening risk, 16 other risks include bronchospasm and wheezing, usually in the context of a respiratory illness, cold hands and feet, gastrointestinal upset, and sleep disturbances. All of these potential adverse events require anticipatory guidance of parents, which should still be a part of clinical care, whether in person or via telemedicine.

2.3. Other orally administered beta‐blockers and topical beta‐blockers

Other non‐FDA‐approved beta‐blocking agents, including oral atenolol and nadolol, have been used for the treatment of IH with several publications supporting their efficacy. However, the group was unable to reach consensus recommendation regarding telemedicine for initiation of either of these medications. Topical timolol has been widely used for treating IH with efficacy reported, particularly for small, superficial IH. 9 , 15 Systemic absorption is variable but does occur, 17 , 18 suggesting that similar prescreening should be performed to assure that infants are healthy and have had a normal cardiovascular and pulmonary examinations, for example, via recent history and physical examination (see discussion below).

3. RECOMMENDATIONS

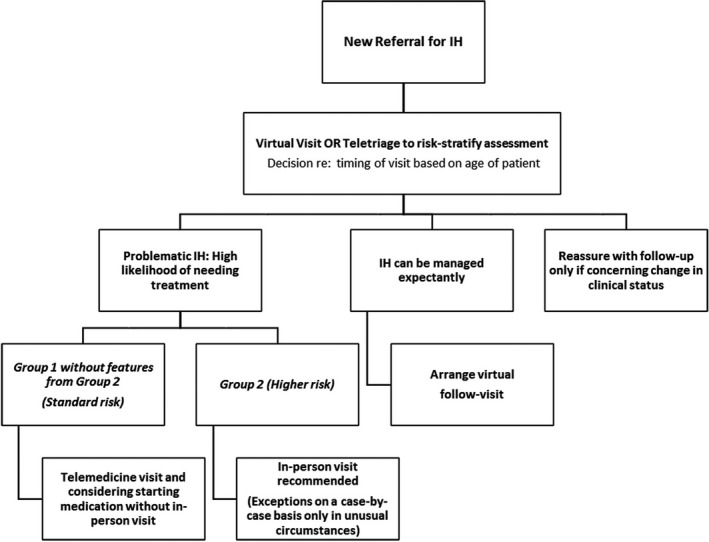

Our recommendations regarding telemedicine initiation of beta‐blocker therapy are summarized in Table 2 with an accompanying algorithm (Figure 1). They were developed after review of relative and absolute contraindications for propranolol, reported adverse events, FDA/EMA labeling recommendations, and published guidelines, with group consensus. They are made with the goal of supporting practicing clinicians in delivering high‐quality care in a dramatically altered care delivery model. They apply primarily to new patients, but also for return patients who are being started on a systemic beta‐blocker.

TABLE 2.

Risk stratification when considering beta‐blocker treatment

|

Group 1 (Standard risk): May consider telemedicine initiation of oral or topical beta‐blocker therapy a as long as infant does not have additional features listed for Group 2

|

|

Group 2 (Higher risk): Recommend in‐person evaluation unless local circumstances make this impossible prior to initiation of systemic beta‐blocker therapy b

|

In ordinary circumstances, infants are being seen regularly for well‐child visits by primary care providers, who weigh and measure infants and perform heart and lung examinations as a standard part of their care. If these examinations are not occurring due to disruptions in healthcare, it becomes much more difficult to ascertain whether there is a normal cardiovascular or pulmonary examination, if normal growth is occurring and other baseline characteristics. In such cases, decisions about initiating therapy must be done on a case‐by‐case basis.

During this pandemic and other unusual circumstances, in‐person visits may not be possible in a timely fashion. In these settings, triage and management decisions need to be made on a case‐by‐case basis, ideally in conjunction with relevant specialists as needed (eg, ENT and cardiology).

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm for management

Group 1 patients have characteristics which confer a standard risk. These infants can be considered as appropriate candidates for telemedicine initiation of oral or topical beta‐blocker therapy even in the absence of an in‐person visit. Group 2 includes patients with higher risk characteristics, where the risk‐benefit ratio favors in‐person visit, not only for propranolol initiation but also to discuss management, risk of extra‐cutaneous disease, and to arrange for imaging studies if needed. These characteristics might be considered relative or absolute exclusion criteria for initiation of medication via telemedicine, particularly systemic beta‐blockers, and for these infants, telemedicine should be used only in exceptional circumstances.

There was broad consensus that in settings where there are not disruptions of ambulatory care delivery, in‐person evaluation for new patients, particularly young infants, is the best approach. Physical examination is more thorough and may provide a more accurate assessment of baseline status including subtle clues (such as duskiness) suggestive of impending ulceration, and the presence of deeper hemangioma not evident with photographs or video without palpation. Other advantages of in‐person assessment include more accurate assessment of weight, confirmation of respiratory and cardiovascular status, and the opportunity for face‐to‐face counseling and establishing rapport with families, the latter being particularly important for infants who need treatment, since the medications used for IH are typically continued for many months or longer.

The most commonly used target doses of propranolol are between 2 and 3 mg/kg/d divided twice daily with FDA/EMA recommendations for starting with 1 mg/kg/d and increasing weekly by 1 mg/kg/d to target dose. However in the context of outpatient initiation via telemedicine, our group unanimously agreed that starting with a lower dose of 0.5 mg/kg/d divided twice daily, and increasing every 3 to 4 days by 0.5 mg/kg/d to the target dose was a preferred approach. A minority commented that in a typical standard risk infant, they would consider starting at 1 mg/kg/d divided twice, increasing in 0.5 mg/k/d increments every 3 to 4 days to target dosing.

There was uniform consensus that in most cases, follow‐up visits can be performed via telemedicine either via two‐way synchronous video or asynchronous store‐and‐forward photographs with telephone counseling as long as it is possible to examine the infant's hemangioma adequately and to provide sufficient parental counseling. Even if video visits are used, having photographs of the IH uploaded shortly before a telemedicine visit is often necessary to be able to adequate evaluate the IH, given the variability of visualization with live‐interactive portals.

Clinical situations which may be less optimal for follow‐up telemedicine visits include diagnostic uncertainty, unexpected IH growth, functional impairment, or significant or worsening ulceration. If there is medication intolerance or lack of efficacy requiring consideration of another treatment modality (eg, transition from topical to systemic therapy or addition of another systemic agent), then providers should consider whether a telemedicine visit is sufficient to address the clinical scenario or if an in‐person visit is indicated.

3.1. Use of topical timolol

Topical timolol is efficacious for smaller, thin IH. 17 , 19 , 20 Although rigorous safety studies have not been performed, if used in small amounts, the rate of adverse events is very low. 19 Systemic absorption occurs to varying degrees measurable in both urine and plasma; plasma concentrations demonstrated to have measurable systemic β‐blocking activity in adults have been reported. 17 , 18 , 21 Based on this information, we recommend that timolol application should be limited to the dose for which safety data have been most often reported, 1 drop twice daily of timolol 0.5%. Timolol is not recommended for the treatment of thick or deep IH, both because it is less effective and systemic absorption may be greater. 18 Because of the potential for systemic exposure of topical application, pre‐screening should be performed to assure that infants are healthy with normal cardiopulmonary examinations via recent history and physical examination. As with oral beta‐blockers, temporary discontinuation is recommended if patients experience respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. Infants under 3 months of age, and those whose history suggests ongoing IH growth, should be monitored via frequent visits or photographs submitted by parents to assure that therapy does not need to be switched from topical to oral. Such follow‐up visits can often be done via telemedicine.

4. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused an abrupt shift from ambulatory visits to telemedicine platforms. This consensus statement provides guidance on timely treatment for patients with IH requiring early intervention while prioritizing patient safety. While we acknowledge the benefits of in‐person visits when health care systems are operating normally, there was group consensus that telehealth visits could provide an alternative method of evaluation and treatment as long as safeguards are in place to minimize risks. Our recommendations are based upon first ensuring that there are no contraindications for therapy, documentation of a recent normal physical examination, and no signs or symptoms of active illness (Table 2). We suggest that these patients are amenable to initiation of therapy through a process of limited physical examination coupled with virtual counseling and education about the natural history, treatment options, administration of medication, and potential adverse reactions to therapy.

We recognize that there are other circumstances in which these recommendations may be applicable including natural disasters (eg, earthquakes, hurricanes). In addition, there are patients whose access to specialty care is severely limited due to geographic constraints (eg, living many hours away from a center with expertise in the evaluation and management of IH) where these recommendations may prove beneficial.

With or without telemedicine, all patients with IH require careful consideration of risks and benefits of any proposed treatment, discussion with families regarding treatment options, and recommendations and information about possible adverse events from prescribed medications (Table 3). For IH still in the rapid growth phase, we recommend particularly close follow‐up, ideally within 1‐2 weeks. Telemedicine is particularly well‐suited for these typically brief follow‐up visits to assure that the IH is behaving as anticipated. Parents should be advised to reach out to practitioners in the context of changes in the IH (eg, ulceration, ongoing growth, development/progression of functional impairment). If the patient develops respiratory symptoms (eg, cough, wheezing, respiratory distress), gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, vomiting, diarrhea, decreased intake), or lethargy, medication should be immediately discontinued and a physician notified. 22 Although infection with COVID‐19 in young infants and toddlers most often does not result in severe symptoms, it can cause symptomatic infection including respiratory illness. Similar to other infections which can result in fever or respiratory symptoms, we recommend temporarily stopping propranolol in the setting of active infant COVID‐19 infection until symptoms from the infection cease. Comprehensive counseling and communication of potential risks and benefits of treatment are of paramount importance both for anticipatory guidance and to help minimize side effects. Online resources (Table 3) can be very helpful both in reinforcing education regarding the diagnosis of IH and specifics of treatment and possible side effects.

TABLE 3.

Online Infantile Hemangioma Resources a

|

General hemangioma information |

|

Beta‐blocker therapy information |

These links created or vetted by HIG members.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Ilona J. Frieden is a member of Venthera Medical Advisory Board; Other: Pfizer (Data Safety Monitoring Board and investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01) Beth A. Drolet reports an investigator‐initiated trial funded by Pierre Fabre, Venthera consultant and medical advisory, and founder of Peds Derm Development, LLC and investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01). Maria C. Garzon MD is an investigaror NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01). Sarah L. Chamlin MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01). Other: Sarah L. Chamlin MD is a consultant in Regeneron and Sanofi. Elena Pope MD investigator in Pierre Fabre. Dawn H. Siegel MD is reviewer in ArQule (expert reviewer) and investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01). Deepti Gupta MD has no conflicts of interest to declare. Anita N. Haggstrom MD is investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01), Anthony J. Mancini MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01), Megha M. Tollefson MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01), Christine T. Lauren MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01), Erin F. Mathes MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01). Eulalia Baselga MD is a consultant and advisory board member in Pierre Fabre, Venthera co‐founder and medical advisor. Kristen E. Holland MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01); Other: Kristen E. Holland MD is an investigator and consultant in Pfizer, consultant in Regeneron, and investigator in Celgene and Sanofi. Denise M. Adams MD is an advisory board member in Venthera and Novartis. Katherine B. Püttgen MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01), Kimberly A. Horii MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01), Kimberly D. Morel MD, is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01), Kimberly A. Horii MD is an investigator NCT02913612 Pediatric Trials Network‐NIH Efficacy, Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Topical Timolol in Infants With Infantile Hemangioma (IH) (TIM01), Brandon D. Newell MD, Catherine C. McCuaig, Amy J. Nopper MD, Denise W. Metry MD, Sheilagh Maguiness and Sonal D. Shah MD have no conflicts of interest to declare. Julie Powell MD is a member of advisory board and speaker in Pierre‐Fabre Dermatology.

Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412–418. 10.1111/pde.14196

REFERENCES

- 1. Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ et al Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20183475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y et al Epidemiology of COVID‐19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020. pii: e20200702. 10.1542/peds.2020-0702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garzon MC, Epstein LG, Heyer GL et al PHACE Syndrome: consensus‐derived diagnosis and care recommendations. J Pediatr. 2016;178:24‐33.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Graaf M, Knol MJ, Totté JE et al E‐learning enables parents to assess an infantile hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):893‐898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Léauté‐Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L et al The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145(4):e20191628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Effective health care program. Diagnosis and management of infantile heamngioma. Available at: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/infantile‐hemangioma/research Accessed March 30, 2020.

- 7. Léauté‐Labrèze C, Hoeger P, Mazereeuw‐Hautier J et al A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):735‐746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hemangeol (propranolol hydrochloride oral solution) [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Pierre Fabre Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robert J, Tavernier E, Boccara O, Mashiah J, Mazereeuw‐Hautier J, Maruani A. Modalities of use of oral propranolol in proliferative infantile hemangiomas: an international survey among practitioners. Br J Dermatol. 2020. 10.1111/bjd.19047. [Epub ahead of print]. PubMed PMID: 32221977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Drolet BA, Frommelt PC, Chamlin SL et al Initiation and use of propranolol for infantile hemangioma: report of a consensus conference. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):128‐140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Putterman E, Wan J, Streicher JL, Yan AC. Evaluation of a modified outpatient model for using propranolol to treat infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(4):471‐476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoeger PH, Harper JI, Baselga E et al Treatment of infantile haemangiomas: recommendations of a European expert group. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(7):855‐865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Solman L, Glover M, Beattie PE et al Oral propranolol in the treatment of proliferating infantile haemangiomas: British Society for Paediatric Dermatology consensus guidelines. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(3):582‐589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smithson SL, Rademaker M, Adams S et al Consensus statement for the treatment of infantile haemangiomas with propranolol. Australasian J Derm. 2017;58(2):155‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Püttgen KB, Hansen LM, Lauren C et al Limited utility of repeated vital sign monitoring during initiation of oral propranolol for complicated infantile hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020. pii: S0190‐9622(20)30553‐3. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.013. [Epub ahead of print]. PubMed PMID: 32289387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wedgeworth E, Glover M, Irvine AD et al Propranolol in the treatment of infantile haemangiomas: lessons from the European Propranolol In the Treatment of Complicated Haemangiomas (PITCH) taskforce survey. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(3):594‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borok J, Gangar P, Admani S, Proudfoot J, Friedlander SF. Safety and efficacy of topical timolol treatment of infantile haemangioma: a prospective trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):e51‐e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Drolet BA, Boakye‐Agyeman F, Harper B et al Systemic timolol exposure following topical application to infantile hemangiomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):733‐736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Puttgen K, Lucky A, Adams D et al Hemangioma Investigator Group. Topical timolol maleate treatment of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20160355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khan M, Boyce A, Prieto‐Merino D, Svensson Å, Wedgeworth E, Flohr C. The role of topical timolol in the treatment of infantile hemangiomas: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(10):1167‐1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weibel L, Barysch MJ, Scheer HS et al Topical timolol for infantile hemangiomas: evidence for efficacy and degree of systemic absorption. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(2):184‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin K, Blei F, Chamlin SL et al Propranolol treatment of infantile hemangiomas: anticipatory guidance for parents and caretakers. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(1):155‐159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]