Short abstract

This commentary focuses on the cytopathology laboratory, the authors' experiences with coronavirus (COVID‐19) in Taiwan, and current guidelines on COVID‐19 infection prevention and control. The objective of this report is to provide cytopathology professionals a timely, in‐depth, evidence‐based review of biosafety practices for those at risk for coronavirus (COVID‐19) infection.

Keywords: biosafety, coronavirus, COVID‐19, cytology, pneumonia

Introduction

The outbreak of a novel coronavirus‐associated acute respiratory disease called coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19) was first detected in China in December 2019, spreading worldwide including in Taiwan to emerge as a pandemic. COVID‐19 is caused by a novel coronavirus and was named severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS–CoV‐2) by the Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 1 As of March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID‐19 a pandemic, 2 and 657,140 cases have been confirmed as of March 29 in 195 countries and territories, with 30,451 deaths. 3 The largest COVID‐19 case series of 72,314 cases in China included 19% individuals with severe symptoms or critical status, 3.8% health care workers, and a mortality rate of 2.3%. 4 Despite the phylogenetic similarities among SARS–CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐CoV), and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV), the differences in the clinical characteristics, such as greater transmissibility, relatively lower frequency of gastrointestinal symptoms, more patients with mild symptoms, and fewer fatalities, distinguish COVID‐19. 4 , 5 , 6

Although characteristics of the transmissibility and natural history of COVID‐19 are only beginning to be defined, confirmed cases of COVID‐19 disease have presented in various ways: sometimes as an asymptomatic infection or, in many cases, as respiratory symptoms ranging from mild to severe, life‐threatening pneumonia. 7 , 8 Notably, COVID‐19 appears to be transmitted early during the incubation period, when patients with COVID‐19 either lack symptoms or have nonspecific symptoms. 9 , 10 Several issues have complicated the diagnosis and management of patients with COVID‐19, including the availability of point‐of‐care diagnostic assays, although, at the time of writing this article, rapid advances are being made in fast on‐site testing. With regard to health care professionals, they are at risk of exposure to the virus because of several factors, including contact with asymptomatic individuals or patients with nonspecific symptoms who are potential sources of COVID‐19 infection, 11 limited availability of personal protective equipment (PPE), the concealing of epidemiological histories, and inadequate training for infectious outbreaks in some health care departments. In addition, laboratory professionals, including pathologists and cytopathologists, are also at potential risk through exposure to certain patient specimens.

This commentary focuses on the cytopathology laboratory, our experiences in Taiwan, and current guidelines on infection prevention and control.

COVID‐19 in Taiwan

On January 21, 2020, the Taiwanese Central Epidemic Command Center announced the first confirmed COVID‐19 case in Taiwan: a woman aged >50 years who was working in Wuhan, China, and was taking a flight to Taiwan for the Lunar New Year. Because Taiwan has 23 million citizens, of whom 850,000 reside in China and 404,000 work in China, it was subsequently expected that Taiwan would have the second highest number of COVID‐19 cases. 12 However, as of March 28, 2020, a cumulative total of 283 COVID‐19 cases were confirmed in Taiwan among 29,389 suspected cases. Of these 283 cases in Taiwan, 241 were imported, and 42 were indigenous.

Taiwan's case numbers were far fewer than the initial model's prediction, in part because the government responded quickly and instituted specific approaches for case identification, containment, and resource allocation to protect the public health. 13 In Taiwan, all cytopathology laboratories and other clinical laboratories strictly followed the guidance and instructions of the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. In response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control implemented a laboratory biosafety checklist in January 14 and provided timely updates of its guidance for transporting, packing, handling, and processing specimens associated with COVID‐19. 15 To date, no biohazard events have been reported to be associated with COVID‐19 in medical laboratories in Taiwan.

Body Fluids and Virus Transmission

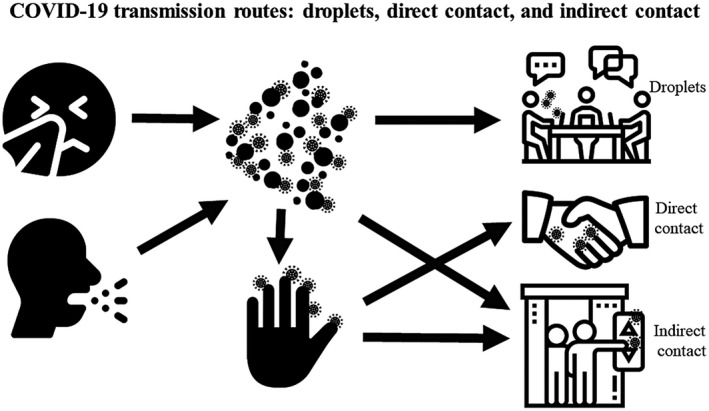

A thorough understanding of the routes of SARS–CoV‐2 transmission is essential for prevention and biosafety. The major routes of transmission of SARS–CoV‐2 are believed to be person‐to‐person transmission through respiratory droplets, close unprotected contact with an infectious individual, and touching items that have been contaminated (Fig. 1). 16 , 17 Droplet transmission is spread by small droplet nuclei >5 µm in diameter that can travel in the air through a short distance (usually <1 meter). Airborne transmission (droplet nuclei <5 µm in diameter and traveling >1 meter) is currently not evident but may play a role if certain aerosol‐generating procedures are conducted. 18 The fecal‐oral route is not a significant driver of COVID‐19 transmission, but it warrants further investigation. 18 , 19 , 20

Figure 1.

Drivers of transmission of coronavirus (COVID‐19) infection consist of short‐range, large‐droplet transmission (>5 µm in diameter, traveling <1 meter); close, unprotected, direct contact; and indirect contact with contaminated surfaces.

To date, there are limited data concerning the detection of SARS–CoV‐2 RNA and viable virus particles in clinical specimens; however, with molecular approaches, such as next‐generation sequencing or real‐time reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction, SARS–CoV‐2 RNA has been detected in a wide range of upper and lower respiratory tract specimens (eg, sputum samples, oral swabs, nasopharyngeal swabs, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid) as well as anal swabs, feces, blood, tears, and conjunctival secretions. 5 , 8 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 The precise timeframe for the shedding of SARS–CoV‐2 RNA in upper and lower respiratory tract specimens and in extrapulmonary specimens from infected patients remains unknown but could be several weeks. However, the detection of viral RNA is not equivalent to the detection of a live infectious virus.

Because polymerase chain reaction assays only detect a small portion of RNA, they cannot replace culture‐based methods in determining viability. Viable SARS–CoV‐2 virus had been isolated from upper respiratory tract specimens and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples, but not from other clinical samples. 18 , 24 Cytopathic effects, such as a lack of beating cilia and bronchial epithelial denudation using light microcopy, were observed 96 hours after inoculation on surface layers of human airway epithelial cells. 24 Although the existence of infectious SARS–CoV‐2 in extrapulmonary specimens remains to be defined, the infectious SARS‐CoV that caused a global outbreak in 2003 was isolated from respiratory, urine, and fecal specimens. 25

Specimen Collection, Transportation, Handling, and Processing

Among the various routinely processed cytology samples, upper and lower respiratory tract specimens, including pleural effusion, bronchoalveolar lavage, bronchoalveolar washing, transbronchial needle aspiration, and sputum samples, are deemed to be the most potentially infectious. Our laboratories in Taiwan have followed WHO guidelines to avoid potential exposures. To prevent unintentional exposure to pathogens or their accidental release, the WHO recently published guidance on specimen collection, transportation, and storage for suspected COVID‐19 cases, 26 as summarized in Table 1. All specimens collected for laboratory testing should be considered potentially infectious. Generally, all specimens should be collected in appropriate containers, transported at 2°C to 8°C, and stored at 2°C to 8°C (short term) or −70°C (long term; on a dry‐ice pack) until testing is performed. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has echoed WHO guidance and announced that clinical laboratories should collect specimens for routine testing of respiratory pathogens and store these specimens at 2°C to 8°C within 72 hours after collection or at −70°C in cases for which there will be a delay in testing. 27 , 28

Table 1.

Specimen Collection, Transportation, and Storage a

| Specimen Type | Collection Materials | Transport to Laboratory | Storage Until Testing | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs | Dacron or polyester flocked swabs | 2°C‐8°C | ≤5 d, 2°C‐8°C | The nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs should be placed in the same tube to increase the viral load |

| >5 d, −70°C (dry ice) | ||||

| Bronchoalveolar lavages | Sterile container | 2°C‐8°C | ≤48 h, 2°C‐8°C | There may be some dilution of the pathogen, but it is still a worthwhile specimen |

| >48 h, −70°C (dry ice) | ||||

| (Endo)tracheal aspirates, nasopharyngeal or nasal wash/aspirates | Sterile container | 2°C‐8°C | ≤48 h, 2°C‐8°C | |

| >48 h, −70°C (dry ice) | ||||

| Sputum | Sterile container | 2°C‐8°C | ≤48 h, 2°C‐8°C | Ensure that the material is from the lower respiratory tract |

| >48 h, −70°C (dry ice) | ||||

| Tissue from biopsy or autopsy including from the lung | Sterile container with saline | 2°C‐8°C | ≤24 h, 2°C‐8°C | |

| >24 h, −70°C (dry ice) | ||||

| Serum | Serum separator tubes (adults, collect 3‐5 mL whole blood) | 2°C‐8°C | ≤5 d, 2°C‐8°C | Collect paired samples: |

| >5 d, −70°C (dry ice) |

|

|||

| Whole blood | Collection tube | 2°C‐8°C | ≤5 d, 2°C‐8°C | For antigen detection, particularly in the first wk of illness |

| >5 d,−70°C (dry ice) | ||||

| Stool | Stool container | 2°C‐8°C | ≤5 d, 2°C‐8°C | |

| >5 d, −70°C (dry ice) | ||||

| Urine | Urine collection container | 2°C‐8°C | ≤5 d, 2°C‐8°C | |

| >5 d, −70°C (dry ice) |

Data are based on World Health Organization interim guidance. 26

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Recommendations and guidance on safe handling and processing of specimens with suspected COVID‐19 infection were published by the WHO, 29 , 30 the US CDC, 31 , 32 the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, 33 , 34 and Asian countries, such as Taiwan, 14 , 15 and China. 35 On the basis of our experience in Taiwan, we use a stepwise biosafety strategy for general cytopathology practices based on WHO guidelines (Table 2). 29 , 30 , 36 The cytopathology biosafety strategy for COVID‐19 infection includes a combination of education and supply, environmental protection, transportation, handling and processing, and special recommendations for rapid on‐site evaluations (ROSE). For education and supply, the US CDC recommends that all laboratories perform a site‐specific and activity‐specific risk assessment, which depends on the procedures performed, identification of the biohazards, the competency level of the laboratory workers, the laboratory equipment and facility, and the resources that are available. 31 Moreover, the WHO recommends that the laboratory director provide proper employee training, updates about COVID‐19 infection, adequate PPE supplies, and counseling resources, and ensure that all professionals follow basic good microbiological practices and procedures for laboratory biosafety. 29 , 36

Table 2.

A Summary of Biosafety Recommendations to Prevent Coronavirus (COVID‐19) for Cytopathology Laboratories a

| Education and supply |

|

| Environmental protection |

|

| Transportation |

|

| Handling and processing |

|

| ROSE for FNA and EUS‐FNA |

|

| ROSE for EBUS‐TBNA |

|

Abbreviations: BSL‐2, biosafety level 2; EBUS‐TBNA, endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration; EU, European Union; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound‐guided; FFP2, European Union filtering face piece Class 2; National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; NIOSH, FNA, fine‐needle aspiration; PPE, personal protective equipment; ROSE, rapid on‐site examination.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

Because SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV, and the influenza virus, especially from human secretions, can survive on dry surfaces for extended periods of time, 37 SARS‐CoV may have a similar viability, requiring enhanced cleaning and disinfection of surfaces to assure effective infection prevention and control. The disinfectants with proven activity against enveloped viruses include 0.1% sodium hypochlorite, 62% to 71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, quaternary ammonium compounds, and phenolic compounds. 29 , 38 , 39 Other biocidal agents, such as benzalkonium chloride (0.05%‐0.2%) and chlorhexidine digluconate (0.02%), are less effective. 39 Although both formalin and alcohol solutions with >70% alcohol are considered effective to inactivate SARS–CoV‐2, it is unknown whether fixatives using alcohol solutions with lower concentrations, such as PreservCyt and CytoLyt (Hologic, Inc) and SurePath (Becton, Dickinson and Company), are adequately inactivating for SARS–CoV‐2. 40 In addition, the WHO has recommended establishing a blame‐free environment for workers to report incidents, encouraging self‐assessment and symptom reporting, and arranging appropriate work hours with breaks. 36

Clinical specimens from suspected or confirmed COVID‐19–positive patients should be transported as UN3373 Biological Substance Category B. 31 The packaging for UN3373 consists of 3 components: 1) a leak‐proof primary receptacle, 2) a leak‐proof secondary packaging, and 3) an outer packaging of adequate strength with at least 1 surface having minimum dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm. All specimens are delivered by hand instead of using pneumatic tube systems, and the personnel who transport specimens are trained in safe handling practices and spill decontamination procedures. The submitting health care professional should give the laboratory timely notification that the specimen is being transported. In addition, it is very important that all specimens are correctly labeled with essential information on standard requisition forms.

Before handling and processing specimens, cytopathology professionals should wear appropriate PPE. It is advised that laboratory professionals wear standard medical masks or N95 respirators, goggles, gowns or aprons, and disposable gloves as a basic protection. 16 The US CDC has recommended that any procedure with the potential to generate aerosols or droplets (eg, vortexing, centrifuging, pipetting) should be performed in a certified Class II biosafety cabinet (BSC). If there is no certified Class II BSC available, or if the instruments (eg, centrifuges) cannot be used inside a cabinet, then extra precautions should be followed to provide a barrier between the specimen and the laboratory specialists. 31 Because cytopathology belongs to nonpropagative diagnostic laboratory works according to the WHO definition, manual decapping and opening containers, splitting or diluting samples, vortexing, centrifuging, pipetting, mixing, and preparation for staining on smears should be conducted using procedures equivalent to biosafety level 2. 29 All technical procedures are performed in a way that minimizes the generation of aerosols and droplets, and work surfaces are routinely decontaminated after completion of the procedure. Moreover, performing frozen sections on suspected or confirmed COVID‐19–positive cases should be avoided unless the laboratory is confident that aerosols are contained within the cryostat. 39

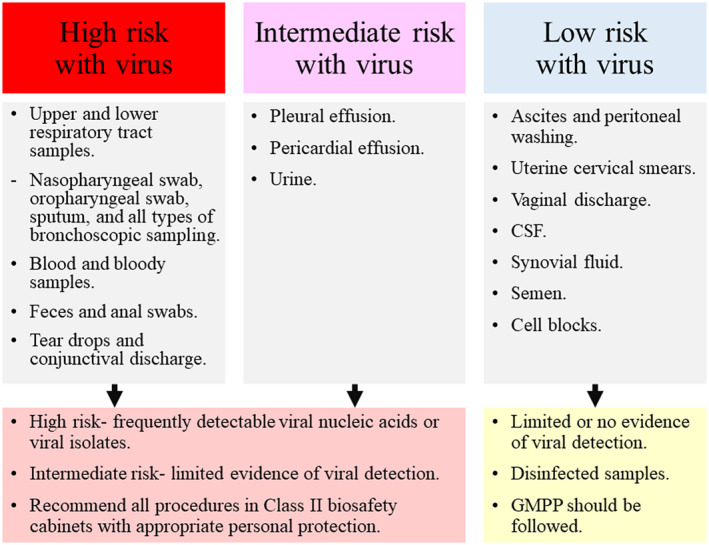

Because viral nucleic acids or cultured viral isolates have been detected in different types of clinical samples, cytopathology specimens can be categorized into 3 groups: high‐risk, intermediate‐risk, and low‐risk for COVID‐19 infection (Fig. 2). 5 , 8 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 Because formalin fixation and paraffin embedding can inactivate SARS–CoV‐2, 39 cell blocks would be categorized into the low‐risk group. It is recommended that high‐risk and intermediate‐risk samples be processed in a Class II BSC with appropriate PPE and that processing for any low‐risk samples be performed using standard good microbiological practices and procedures. 16 , 29 Both the WHO and the US CDC have recommended that virus isolation should not be performed in clinical laboratories. 26 , 28

Figure 2.

According to the frequency and viability of viral detection in published articles, cytopathology samples could be categorized into 3 groups, high‐risk, intermediate‐risk, and low‐risk for coronavirus (COVID‐19) infection. 5 , 8 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 The high‐risk and intermediate‐risk samples are recommended to be processed in a Class II biosafety cabinet with appropriate personal protection equipment, whereas the processing for low‐risk samples can be done using good microbiological practices and procedures (GMPP). 16 , 29 CSF indicates cerebrospinal fluid.

Precautions for Cytopathology Professionals Performing Rose or Fine‐Needle Aspiration

Although most cytotechnologists and cytopathologists have limited patient contact, the specialists who perform fine‐needle aspiration (FNA) or ROSE may be at increased risk for exposure to COVID‐19. ROSE is particularly useful in the assessment of lesions from deep‐seated organs sampled nonsurgically using radiologic guidance, such as endoscopic ultrasound‐guided (EUS)‐FNA and endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS‐TBNA). Because COVID‐19 is highly contagious and may transmit viral particles through respiratory droplets in contaminated samples and equipment, the performance of FNA or ROSE warrants an advanced biosafety policy to prevent infections.

On the basis of the experience with SARS in 2003, the use of a dedicated sonography room and associated equipment can decrease the risk for transmission from patients that have suspected or confirmed COVID‐19. 45 , 46 When performing FNA, including EUS‐FNA, empiric contact and droplet precautions should be implemented, including a procedure room with adequate ventilation and air flow at 60 liters per second per patient; standard preprocedure and postprocedure hand hygiene should be performed; and PPE, including surgical masks, eye protection, water‐resistant gowns or waterproof aprons, and gloves, should be used and properly disposed of at the conclusion of the procedure.

EBUS‐TBNA has the potential to pose an even greater risk for exposure to virus because it is an aerosol‐generating procedure. Health care workers involved in this protocol should follow the WHO guidance on airborne precautions for aerosol‐generating procedures. 30 First, the EBUS‐TBNA should be conducted in an adequately ventilated room with air flow of at least 160 liters per second per patient or in a negative pressure room with at least 12 air changes per hour. 30 Second, those conducting the test should wear particulate respirators, eye protection, gloves, and long‐sleeved, water‐resistant gowns or waterproof aprons. The WHO recommends that respirators should be National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health‐certified N95, European Union filtering face pieces Class 2 (FFP2) equivalent, or a higher level of protection. 30 Third, the number of individuals present in the procedure room should be kept to a minimum. Fourth, hand hygiene should be performed before and after contact with the patient and the surroundings and after PPE removal. All materials that were used during the EBUS‐TBNA should be appropriately disposed of, work areas disinfected, and possible spills of blood or infectious body fluids decontaminated with effective disinfectants. The precautions mentioned above are summarized in Table 2. An awareness of methods for the prevention of infection in health care professionals who perform ROSE or FNA is essential because following established biosafety recommendations will help avoid nosocomial infection.

Conclusion

COVID‐19 is unique, differing from other human coronaviruses by its combination of high transmissibility, its increased mortality among the elderly and those with chronic disease, and its ability to cause major socioeconomic disruption. While confronting the global spread of COVID‐19, the effectiveness of the health system is critical for building public trust and ultimately eliminating infection. Laboratory biosafety, including administrative strategies and containment principles, practices, and procedures, is an important aspect of this. Following guidelines recommended by the WHO, US CDC, and the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, as described above, our cytology laboratories in Taiwan, along with other laboratories around the world, are using a strategy that is crucial for the prevention of COVID‐19 infection by our health care professionals and their families.

Funding Support

No specific funding was disclosed.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

The authors made no disclosures.

Please see related articles on pages https://doi.org/10.1002/cncy.22275, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncy.22276, and https://doi.org/10.1002/cncy.22281, this issue.

References

- 1. Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses . The species severe acute respiratory syndrome‐related coronavirus: classifying 2019‐nCoV and naming it SARS–CoV‐2. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:536‐544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) . Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐2019) Situation Report‐51. WHO; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_4 [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control ( ECDC ) . Situation Update Worldwide, as of 29 March 2020. ECDC; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. Published online February 24, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. Published online February 28, 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID‐19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. Published online March 5, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, et al. Transmission of 2019‐nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:970‐971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person‐to‐person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514‐523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Callaway E, Cyranoski D. China coronavirus: six questions scientists are asking. Nature. 2020;577:605‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou P, Huang Z, Xiao Y, Huang X, Fan XG. Protecting Chinese healthcare workers while combating the 2019 novel coronavirus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. Published online March 5, 2020. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gardner L. Update January 31: Modeling the Spreading Risk of 2019‐nCoV. Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering, Center for Systems Science and Engineering; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov-model-2 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID‐19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. Published online March 3, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taiwan Centers for Disease Control . Laboratory Biosafety Checklist for Medical Laboratories Handling Specimens With the Novel Coronavirus, 2019‐nCoV [in Chinese]. Taiwan Centers for Disease Control; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov.tw/File/Get/OgiAj0wKREECPgQvFwUqOQ [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taiwan Centers for Disease Control . Laboratory Biosafety Guidance Related to SARS–CoV‐2 [in Chinese]. Taiwan Centers for Disease Control; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov.tw/File/Get/ZGt2DPrzrqK8KX-KoDL8yw [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization (WHO) . Rational Use of Personal Protective Equipment for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Interim Guidance, 19 March 2020. WHO; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331498/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPCPPE_use-2020.2-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu YC, Chen CS, Chan Y. The outbreak of COVID‐19: an overview. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83:217‐220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization (WHO) . Report of the WHO‐China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). WHO; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang J, Wang S, Xue Y. Fecal specimen diagnosis 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia. J Med Virol. Published online March 3, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yeo C, Kaushal S, Yeo D. Enteric involvement of coronaviruses: is faecal‐oral transmission of SARS–CoV‐2 possible? Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:335‐337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019‐nCoV infected patients: implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:386‐389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Young BE, Ong SWX, Kalimuddin S, et al. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS–CoV‐2 in Singapore. JAMA. Published online March 3, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xia J, Tong J, Liu M, Shen Y, Guo D. Evaluation of coronavirus in tears and conjunctival secretions of patients with SARS–CoV‐2 infection. J Med Virol. Published online February 26, 2020. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chan KH, Poon LL, Cheng VC, et al. Detection of SARS coronavirus in patients with suspected SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:294‐299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization (WHO) . Laboratory Testing for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Suspected Human Cases. Interim Guidance, 19 March 2020. WHO; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1272454/retrieve [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Evaluating and Testing Persons for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). CDC; 2019. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/clinical-criteria.html [Google Scholar]

- 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Interim Guidelines for Collecting, Handling, and Testing Clinical Specimens From Persons for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). CDC; 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization (WHO) . Laboratory Biosafety Guidance Related to Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19). Interim Guidance, 19 March 2020. WHO; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331500/WHO-WPE-GIH-2020.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1%26isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization (WHO) . Infection Prevention and Control During Health Care When Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection Is Suspected. Interim Guidance, 19 March 2020. WHO; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1272420/retrieve [Google Scholar]

- 31. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Interim Laboratory Biosafety Guidelines for Handling and Processing Specimens Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). CDC; 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/lab/lab-biosafety-guidelines.html [Google Scholar]

- 32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Frequently Asked Questions About Biosafety and COVID‐19. CDC; 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/biosafety-faqs.html [Google Scholar]

- 33. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control ( ECDC ) . ECDC Technical Report: Infection Prevention and Control for COVID‐19 in Healthcare Settings. ECDC; 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/COVID-19-infection-prevention-and-control-healthcare-settings-march-2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34. European Committee for Standardization (CEN) . CEN Workshop Agreement (CWA) 15793—Laboratory Biorisk Management. CEN; 2011. Accessed March 15, 2020. https://www.uab.cat/doc/CWA15793_2011 [Google Scholar]

- 35. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China . Laboratory Biosafety Guide of 2019 Novel Coronavirus, Version 2 [in Chinese]. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 2020. Accessed March 15, 2020. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202001/0909555408d842a58828611dde2e6a26.shtml [Google Scholar]

- 36. World Health Organization (WHO) . Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) Outbreak: Rights, Roles and Responsibilities of Health Workers, Including Key Considerations for Occupational Safety and Health. WHO; 2020. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-rights-roles-respon-hw-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=bcabd401_0 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Otter JA, Donskey C, Yezli S, Douthwaite S, Goldenberg SD, Weber DJ. Transmission of SARS and MERS coronaviruses and influenza virus in healthcare settings: the possible role of dry surface contamination. J Hosp Infect. 2016;92:235‐250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kampf G. Potential role of inanimate surfaces for the spread of coronaviruses and their inactivation with disinfectant agents. Inf Prev Prac. 2020;2:100044. doi: 10.1016/j.infpip.2020.100044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Henwood AF. Coronavirus disinfection in histopathology. J Histotechnol. Published online ahead of print March 1, 2020. doi: 10.1080/01478885.2020.1734718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pambuccian SE. The COVID‐19 pandemic: implications for the cytology laboratory. J Am Soc Cytopathol. Published online March 26, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2020.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang X, Sun W, Shang S, et al. Principles and suggestions on biosafety protection of biological sample preservation during prevalence of coronavirus‐infected disease‐2019 (COVID‐19). J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020;49:1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol. Published online March 27, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ling Y, Xu SB, Lin YX, et al. Persistence and clearance of viral RNA in 2019 novel coronavirus disease rehabilitation patients. Chin Med J (Engl). Published online February 28, 2020. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Salehi S, Abedi A, Balakrishnan S, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): a systematic review of imaging findings in 919 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. Published online March 14, 2020. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barkham TM. Laboratory safety aspects of SARS at Biosafety Level 2. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:252‐256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kooraki S, Hosseiny M, Myers L, Gholamrezanezhad A. Coronavirus (COVID‐19) outbreak: what the department of radiology should know. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17:447‐451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]