Abstract

Cost‐effectiveness analysis depends on generalizable health‐state utilities. Unfortunately, the available utilities for cirrhosis are dated, may not reflect contemporary patients, and do not capture the impact of cirrhosis symptoms. We aimed to determine health‐state utilities for cirrhosis, using both the standard gamble (SG) and visual analog scale (VAS). We prospectively enrolled 305 patients. Disease severity (Child‐Pugh [Child] class, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease with sodium [MELD‐Na] scores), symptom burden (sleep quality, cramps, falls, pruritus), and disability (activities of daily living) were assessed. Multivariable models were constructed to determine independent clinical associations with utility values. The mean age was 57 ± 13 years, 54% were men, 30% had nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, 26% had alcohol‐related cirrhosis, 49% were Child class A, and the median MELD‐Na score was 12 (interquartile range [IQR], 8‐18). VAS displayed a normal distribution with a wider range than SG. The Child‐specific SG‐derived utilities had a median value of 0.85 (IQR, 0.68‐0.98) for Child A, 0.78 (IQR, 0.58‐0.93) for Child B, and 0.78 (IQR, 0.58‐0.93) for Child C. VAS‐derived utilities had a median value of 0.70 (IQR, 0.60‐0.85) for Child A, 0.61 (IQR, 0.50‐0.75) for Child B, and 0.55 (IQR, 0.40‐0.70) for Child C. VAS and SG were weakly correlated (Spearman's rank correlation coefficient, 0.12; 95% confidence interval, 0.006‐0.23). In multivariable models, disability, muscle cramps, and MELD‐Na were significantly associated with SG utilities. More clinical covariates were significantly associated with the VAS utilities, including poor sleep, MELD‐Na, disability, falls, cramps, and ascites. Conclusion: We provide health‐state utilities for contemporary patients with cirrhosis as well as estimates of the independent impact of specific symptoms on each patient’s reported utility.

Abbreviations

- ADL

activities of daily living

- Child

Child‐Pugh

- CI

confidence interval

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- HRQOL

health‐related quality of life

- IQR

interquartile range

- MELD‐Na

Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease with sodium

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- rs

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

- SG

standard gamble

- VAS

visual analog scale

Cirrhosis is increasingly common and morbid. Since the 2000s, its U.S. prevalence has risen by 50%,( 1 ) cirrhosis‐related hospitalizations have increased by 90%,( 2 ) and its mortality has risen by 65%.( 3 ) Cirrhosis is associated with a substantial symptom burden that diminishes the patient’s health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) and causes disability, which in turn affects the HRQOL and productivity of their caregivers.( 4 , 5 ) Interventions and therapies aimed at improving HRQOL carry increased costs. The value of any intervention, however, is defined not only by the magnitude of the investment required but also by its ability to improve quality‐adjusted life‐years (QALYs). To compute QALYs and evaluate the cost‐effectiveness of an intervention, representative health‐state utility data are needed.

Health‐state utilities reflect the multidimensionality of the patient’s present health status. Utilities are ideally derived directly from patients using exercises that allow them to make a quantifiable assessment of the quality of their life on a relative scale from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health).( 6 ) Unfortunately, published utilities may not accurately represent contemporary persons with cirrhosis. The epidemiology of cirrhosis has shifted, now characterized by aging persons with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), alcohol‐related disease, or treated hepatitis C.( 7 )

Cost‐effectiveness analyses depend on generalizable utilities but continue to use extremely dated values that are often more than 20 years old and derived from patients with viremic hepatitis C, few of whom had decompensated cirrhosis and few of which capture the contribution of specific cirrhosis symptoms.( 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ) Updated heath‐state utilities are therefore needed in order to execute meaningful cost‐effectiveness studies that represent contemporary patients. Herein, we prospectively evaluated health‐state utilities in a large cohort of patients with cirrhosis.

Materials and Methods

From December 2018 to June 2019, we prospectively administered verbal in‐person surveys to 305 English‐speaking adults with cirrhosis presenting to the University of Michigan outpatient Hepatology clinic and inpatient Hepatology ward. At the time of their enrollment, no patient had altered mental status, as assessed by their treating clinician and confirmed by a trained research assistant. All subjects provided written consent.

Health‐State Utilities

Health‐state utility was measured on a scale of 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health) using two validated tools, the visual analog scale (VAS) and the standard gamble (SG). Subjects were told to consider both the physical and emotional influences of their quality of life only in the moment that their survey response was elicited. The VAS asked subjects to rate their own quality of life on a thermometer scale from 0 (representing the worst imaginable health state) to 100 (representing the best imaginable health state). Population means ± SD for the VAS are variable and have been reported as 71.3 ± 19.2 or lower.( 12 , 13 ) VAS scores are always lower than values derived from the SG,( 13 , 14 ) likely because of the framing (SG deals in uncertainty in the face of mortal risk). The SG activity presented patients with a thought experiment. It asked them to imagine that there was a hypothetical magic pill that had a certain probability (p) of completely curing them of all negative effects of their health conditions and a certain probability (1 – p) of leading to an immediate and painless death. Importantly, subjects were told that, if cured, the remaining duration of their life would remain unaffected despite the quality of their remaining years increasing from their enhanced health. A computer algorithm was used to incrementally vary these probabilities with a ping‐pong approach.( 15 ) At each stage, subjects observed the probabilities visually through pie charts and decided whether they would take the hypothetical magic pill. This continued until the subject reached the point of indifference (POI), defined as the point at which the subject was indifferent to either taking the magic pill or not taking the magic pill. The utility was calculated as the probability of being cured by the magic pill at the POI.

Clinical Covariates

We collected demographic, etiologic, and disease severity data for each subject and confirmed all data with reference to the medical record. Disease severity was assessed through the Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease with sodium (MELD‐Na) score and Child‐Pugh [Child] classification (A‐C). Ascites grading and West Haven grading of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) were assessed at the time of enrollment as was the need for paracentesis, diuretics, and/or lactulose. The history of hepatocellular carcinoma was also confirmed using the medical record. All laboratory data used for these calculations were extracted from medical records within 4 weeks of enrollment. In addition, patients were surveyed for symptoms known to influence quality of life. Each subject was asked whether they had experienced several of the common symptoms associated with cirrhosis, including falls, muscle cramps, severe itching, and leg edema. The time frame for each of these symptoms was within the last 6 months. Patients who were not currently hospitalized were asked if they had been hospitalized within the past 90 days. Functional disability was assessed by a Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale with disability defined dichotomously as the inability to execute at least one ADL (Supporting Table S1). Subjects were asked the summary question from the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index,( 16 ) namely to rate their sleep quality as either very good, good, neither good nor bad, bad, or very bad.

Analysis

We evaluated the construct validity of our health‐state utility assessments by administering them to 27 healthy controls. To obtain the responses of healthy controls who reported not having liver disease, we administered an anonymous online‐survey questionnaire using the Amazon MTurk platform. This platform provides control data that are equivalent to in‐person surveys of healthy controls enrolled from convenience samples.( 17 ) In order to ensure that we were using only active online participants (as opposed to those who passively clicked through the exercise), we included a test of attention. All respondents were told that cirrhosis is the twelfth leading cause of death, and we only included responses from those who correctly recalled the ranking. We evaluated the correlation between SG and VAS values using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient [rs]. To evaluate the independent associations between cirrhosis symptoms and health‐state utilities, we performed a multivariable forward‐selection linear regression model using a minimum Akaike information criterion with forced inclusion of MELD‐Na.

Results

Cohort Description

We enrolled 305 patients in our study. The demographic characteristics and clinical data are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 57 ± 13 years, 54% were men, more than 63% achieved higher than a high school diploma, 49% were Child A, 37% were Child B, 14% were Child C, and the median MELD‐Na score was 12 (interquartile range [IQR], 8‐18). NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatoheptitis (NASH) (30%) was the most common etiology followed by alcohol (26%) and aviremic/cured‐hepatitis C virus (14%). Overall, 44% of patients had a history of HE, with 42% actively taking lactulose. A majority (60%) of patients had limited to no ascites at enrollment, 62% were currently on diuretics, and 10% had moderate to large ascites requiring serial paracentesis. The majority (64%) reported muscle cramps. The burden of symptoms stratified by Child class is detailed in Supporting Table S2. The 27 included healthy controls were 70% men aged 31 ± 9 years, 78% with a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 70% taking ≤1 medication.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Population

| Adults With Cirrhosis (n = 305) | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 57.68 (13.20) |

| Male sex, % | 54.4 |

| Education level, % | |

| Less than high school | 9.2 |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 23.28 |

| Attended some college (no degree) | 28.52 |

| Trade/technical/vocational training | 3.61 |

| Associate degree | 8.20 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 13.44 |

| Greater than bachelor’s degree | 14.82 |

| Causes, % | |

| Alcohol/NAFLD/HCV/HBV/PBC/PSC/Other | 26.26/29.84/13.44/1.64/4.92/3.61/11.15 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 6.85 |

| Child class A/B/C, % | 49.51/36.72/13.77 |

| MELD‐Na, median (IQR) | 12 (8‐18) |

| Albumin, median (IQR) | 3.60 (3.10‐4.20) |

| Bilirubin, median (IQR) | 1.30 (0.70‐2.80) |

| INR, median (IQR) | 1.20 (1.10‐1.40) |

| Independent in all ADLs, % | 68.85 |

| Fluid overload, % | |

| Any history of ascites | 46.23 |

| Moderate‐large ascites | 10.65 |

| Diuretics | 61.97 |

| Leg edema | 55.74 |

| HE, % | 43.61 |

| Any history of HE | 43.61 |

| Actively taking lactulose | 41.97 |

| Falls | 26.56 |

| Muscle cramps | 63.61 |

| Pruritus | 38.69 |

| Stopped driving | 22.95 |

| Hospital admission in prior 90 days | 35.08 |

Abbreviations: HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; INR, international normalized ratio; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Overall Health‐State Utilities

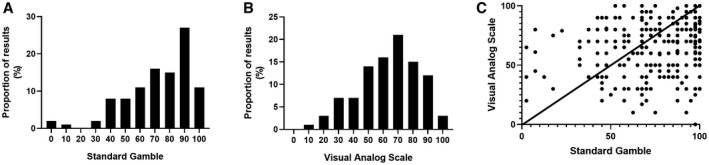

The mean health‐state utilities derived from the SG and VAS are presented in Table 2. The distribution of utilities across the study sample is displayed in Fig. 1A,B. The SG takes a nonparametric right‐shifted distribution, while the VAS follows a normal distribution. Utilities are plotted against each other in Fig. 1C, demonstrating a weak correlation (rs, 0.12; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.006‐0.23; P = 0.04). Patients with Child A produced a higher median utility for both the SG and the VAS compared to patients with Child B and Child C. The SG produced a median utility of 0.85 (IQR, 0.68‐0.98) for Child A, 0.78 (IQR, 0.58‐0.93) for Child B, and 0.78 (IQR, 0.58‐0.93) for Child C. The VAS produced a median utility of 0.70 (IQR, 0.60‐0.85) for Child A, 0.61 (IQR, 0.50‐0.75) for Child B, and 0.55 (IQR, 0.40‐0.70) for Child C. Twenty‐seven healthy controls completed the same SG and VAS prompts. Overall, healthy controls reported higher health‐state utilities using both the SG and the VAS with scores of 0.98 (IQR, 0.82‐1.00) and 0.74 (IQR, 0.64‐0.88), respectively.

Table 2.

Health‐State Utilities With Univariable Associations

| Health‐State Utilities | ||

|---|---|---|

| SG | VAS | |

| Overall | 0.83 (0.65‐0.98) | 0.70 (0.50‐0.80) |

| Child A | 0.85 (0.68‐0.98) | 0.70 (0.60‐0.85) |

| Child B | 0.78 (0.58‐0.93) | 0.61 (0.50‐0.75) |

| Child C | 0.78 (0.58‐0.93) | 0.55 (0.40‐0.70) |

| NAFLD | 0.84 (0.66‐0.98) | 0.65 (0.50‐0.80) |

| ALD | 0.78 (0.60‐0.94) | 0.61 (0.50‐0.80) |

| Other etiology | 0.86 (0.68‐0.98) | 0.70 (0.50‐0.81) |

| HE (history of) | 0.78 (0.60‐0.93) | 0.60 (0.50‐0.75) |

| Ascites (moderate‐severe) | 0.75 (0.58‐0.88) | 0.59 (0.40‐0.70) |

| Any ADL disability | 0.80 (0.53‐0.93) | 0.60 (0.40‐0.70) |

| Recent hospitalization | 0.78 (0.60‐0.98) | 0.60 (0.45‐0.70) |

| Cramps | 0.78 (0.58‐0.95) | 0.63 (0.50‐0.76) |

| Falls | 0.78 (0.58‐0.96) | 0.60 (0.40‐0.75) |

| Poor sleep | 0.78 (0.58‐0.98) | 0.55 (0.40‐0.70) |

| Pruritus | 0.85 (0.65‐0.98) | 0.60 (0.50‐0.80) |

| Recently stopped driving | 0.78 (0.58‐0.93) | 0.63 (0.49‐0.74) |

Abbreviation: ALD, alcohol‐related liver disease.

Fig. 1.

Health‐state utilities, distributions, and correlation. (A) The distribution of health‐state utilities obtained by SG demonstrates a right skew. (B) The distribution of health‐state utilities obtained by VAS demonstrates a normal distribution with a wider range than observed for the SG. (C) In the plot of each patient’s VAS and SG results, there is a limited correlation (rs, 0.12; 95% CI 0.006‐0.23).

Health‐State Utilities According to Symptom

There were minimal variations among the mean health‐state utilities reported for the SG for each cirrhotic symptom. However, there was substantially more variance in health utilities when evaluating the impact of symptoms on the VAS. For example, the utility associated with HE for the SG fell 8% from 0.85 in Child A to 0.78 in Child A with a history of HE; for the VAS, the utility fell 14% from 0.70 to 0.60, respectively. A tabulation of utilities stratified by ADLs is provided in Supporting Table S3.

Independent Associations with Utility

Our linear regression model showed that disability and muscle cramps were significantly associated with the SG utilities. The respective coefficients were –2.95 (–5.67 to –0.23) and –2.72 (–5.29 to –0.15). Disease severity, which was assessed through MELD‐Na score, was also associated with the SG utilities, with a coefficient of –0.34 (–0.69 to –0.01). More clinical covariates were associated with the VAS utilities, including poor sleep, MELD‐Na, disability, falls, cramps, and ascites (Table 3).

Table 3.

Independent Associations With Health‐State Utilities

| SG | VAS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Beta Effect Estimate (95% CI) | Covariates | Beta Effect Estimate (95% CI) |

| ADL‐dependence | −2.95 (−5.67 to −0.23) | Poor sleep | −6.20 (−8.38 to −4.01) |

| Cramps | −2.72 (−5.29 to −0.15) | MELD‐Na (per point) | −0.46 (−0.79 to −0.12) |

| MELD‐Na (per point) | −0.34 (−0.69 to −0.01) | ADL‐dependence | −2.95 (−5.32 to −0.58) |

| Falls | −2.57 (−5.01 to −0.14) | ||

| Cramps | −2.16 (−4.40 to −0.08) | ||

| Ascites | −2.75 (−5.63 to −0.12) | ||

Multivariable linear regression models were constructed using a forward‐selection procedure. For ease of interpretation, the utility scale has been inflated to 0‐100 (from 0 to 1). The beta estimate reflects the number of points on that scale with which each given exposure is associated, adjusting for the others.

Discussion

Cirrhosis poses many physiological and emotional challenges for patients due to the nature of its often debilitating symptoms. Interventions to treat the complications of cirrhosis and resolve chronic liver disease to forestall the development of cirrhosis will have costs that can be offset by their effectiveness in improving one’s present and future HRQOL. Robust health‐state utilities are necessary to perform cost‐effectiveness studies. In this prospective study of a contemporary cohort of patients with cirrhosis, we provide updated utilities to power cost‐effectiveness analyses that evaluate the impact of interventions tailored toward the complications of cirrhosis.

We extend the literature on health utility assessment in cirrhosis with three major findings. First, as expected, we confirm that worsening disease severity (Child class, MELD‐Na) influences health utilities in a cohort that is both larger and more representative of contemporary patients by including persons with NASH, alcohol‐related cirrhosis, and cured/aviremic hepatitis C. In a prior systematic review that recovered only five studies with directly elicited utilities from 202 patients with cirrhosis, nearly all of whom had viremic hepatitis C, decompensation (although not categorized by the Child classification) was independently associated with poor health utility.( 8 ) In their study of patients enrolled in a trial of interferon for hepatitis C, Siebert et al.( 18 ) assessed the VAS for 37 patients with decompensated cirrhosis (mean ± SD, 0.81 ± 0.03) and 74 patients with compensated cirrhosis (mean ± SD, 0.89 ± 0.02). In another study of patients with viremia and hepatitis C, Sherman et al.( 19 ) evaluated the VAS and SG for 29 patients with compensated cirrhosis (mean ± SD, 0.65 ± 0.04 and 0.83 ± 0.04, respectively) and 8 patients with decompensated cirrhosis (mean ± SD, 0.66 ± 0.07 and 0.72 ± 0.12, respectively), and Chong et al.( 20 ) assessed the VAS and SG in another study of patients with viremia and hepatitis C, including 24 patients with compensated cirrhosis (mean ± SD, 0.65 ± 0.04 and 0.80 ± 0.05, respectively) and 9 with decompensated cirrhosis (mean ± SD, 0.57 ± 0.08 and 0.60 ± 0.12, respectively). By enrolling a much larger cohort, we could perform multivariable analyses to demonstrate the specific decrements in health‐state utility associated with decompensated disease. Furthermore, we only enrolled patients with cleared hepatitis C. Younossi et al.( 21 , 22 ) has shown that hepatitis C eradication is associated with marked durable improvements in HRQOL, rendering utilities derived from patients with viremia less generalizable to contemporary cured patients.

Second, we now show that, after adjusting for disease severity, the factors that are significantly linked with poor health utility are disability, muscle cramps, falls, poor sleep, and ascites. As we previously reviewed, it is well known that the symptoms of cirrhosis influence HRQOL.( 5 ) These data, however, are the first to evaluate the independent contributions of cirrhosis symptoms to health utility, holding other factors constant, and underscore the highest yield targets for interventions aimed at improving overall well‐being. These data may help clinicians prioritize the symptoms to be evaluated and addressed during clinical care and could help explain to families and caregivers the disproportionate impact of a symptom when experienced by a patient with cirrhosis.

Third, we show that the VAS appears to be more variable and sensitive to symptoms than the SG. Although the VAS yields systematically lower values,( 8 ) its variance and normal distribution may make it more useful in this population. In a 2004 study of 74 patients with decompensated cirrhosis, Bryce et al.( 23 ) also found that in contrast to other methods, such as the SG, the VAS has a normal distribution and was more strongly associated with validated measures of HRQOL. We extend these data by showing similar effects when examining associations with cirrhosis symptoms. The limited correlation observed between the SG and VAS, furthermore, implies that each may be measuring different factors. While future research may be able to resolve the reasons underlying this discordance, the VAS appears to be more suitable for studies that examine the impact of an intervention on the population with cirrhosis.

These data must be interpreted in the context of the study design. First, this large cohort was derived from a Midwestern U.S. referral center. American patients with cirrhosis are risk averse, potentially more so than patients from abroad.( 24 ) It is therefore unclear whether the framing of the SG in terms of the risk of death led to the lack of variance across symptoms. Second, by querying specific symptoms in our multivariable modeling, some disease‐state effects may have been lost. For example, HE is associated with poor physical and mental health.( 25 ) HE is also associated with falls, poor sleep, and disability.( 26 , 27 ) Accordingly, these data do not suggest that programs to address disability per se should be prioritized as a biomarker or target over the identification and management of HE, only that HE is de‐emphasized in the adjusted models in the presence of its complications. Third, we did not assess recent active alcohol consumption. Fourth, other social factors that could impact utilities, such as marital status, employment, and income, were not queried. The null association between education and utility, however, suggests that if effects could be present for employment and income, they would likely be weak. Fifth, these data may or may not generalize to other direct measures of utility, such as the time tradeoff, or less desirable “indirect” measures of utility, such as the short form (item 36) or EuroQol‐5D. These measures are highly correlated with the VAS but would have added additional information about the validity of our assessments.( 12 , 28 ) Finally, it must be noted that the VAS retrieves utilities that are systematically lower than the SG for persons with cirrhosis as well as healthy controls.( 13 , 14 , 18 ) Although speculative, the reasons for this observation, which was confirmed in our study, likely reflect the framing of the questions, namely that the VAS is open ended and the SG is influenced by uncertainty and risk aversion.

Health‐state utility estimates for persons with cirrhosis required updating. These data provide utility estimates that generalize to the aging population with NAFLD/NASH and treated hepatitis C, diseases that are sensitive to the symptoms of cirrhosis. Our findings will be useful for future cost‐effectiveness analyses that evaluate the economic impact of interventions aimed at patients with or at risk for cirrhosis.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (1K23DK117055‐01A1 to E.T.).

Potential conflict of interest: Dr. Tapper consults for Kaleido, Allergan, Novartis, and Axcella; he advises Bausch, Rebiotix, and Mallinckrodt. The other authors have nothing to report.

References

- 1. Mellinger JL, Shedden K, Winder GS, Tapper E, Adams M, Fontana RJ, et al. The high burden of alcoholic cirrhosis in privately insured persons in the United States. Hepatology 2018;68:872‐882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asrani SK, Kouznetsova M, Ogola G, Taylor T, Masica A, Pope B, et al. Increasing health care burden of chronic liver disease compared with other chronic diseases, 2004‐2013. Gastroenterology 2018;155:719‐729.e714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999‐2016: observational study. BMJ 2018;362:k2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bajaj JS, Wade JB, Gibson DP, Heuman DM, Thacker LR, Sterling RK, et al. The multi‐dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1646‐1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tapper E, Kanwal F, Asrani S, Ho C, Ovchinsky N, Poterucha J, et al. Patient reported outcomes in cirrhosis: a scoping review of the literature. Hepatology 2018;67:2375‐2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wells CD, Murrill WB, Arguedas MR. Comparison of health‐related quality of life preferences between physicians and cirrhotic patients: implications for cost‐utility analyses in chronic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci 2004;49:453‐458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moon AM, Singal AG, Tapper EB. Contemporary epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McLernon DJ, Dillon J, Donnan PT. Health‐state utilities in liver disease: a systematic review. Med Decis Making 2008;28:582‐592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farhang Zangneh H, Wong WW, Sander B, Bell CM, Mumtaz K, Kowgier M, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance after a sustained virologic response to therapy in patients with hepatitis C virus infection and advanced fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:1840‐1849.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klebanoff MJ, Corey KE, Samur S, Choi JG, Kaplan LM, Chhatwal J, et al. Cost‐effectiveness analysis of bariatric surgery for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e190047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chhatwal J, Kanwal F, Roberts MS, Dunn MA. Cost‐effectiveness and budget impact of hepatitis C virus treatment with sofosbuvir and ledipasvir in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:397‐406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shmueli A. The relationship between the visual analog scale and the SF‐36 scales in the general population: an update. Med Decis Making 2004;24:61‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boyd NF, Sutherland HJ, Heasman KZ, Tritchler DL, Cummings BJ. Whose utilities for decision analysis? Med Decis Making 1990;10:58‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Torrance GW, Feeny D, Furlong W. Visual analog scales: do they have a role in the measurement of preferences for health states? Med Decis Making 2001;21:329‐334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hammerschmidt T, Zeitler HP, Gulich M, Leidl R. A comparison of different strategies to collect standard gamble utilities. Med Decis Making 2004;24:493‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hamby T, Taylor W. Survey satisficing inflates reliability and validity measures: an experimental comparison of college and Amazon Mechanical Turk samples. Educ Psychol Measur 2016;76:912‐932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siebert U, Sroczynski G, Rossol S, Wasem J, Ravens‐Sieberer U, Kurth B, et al.; German Hepatitis C Model ( GEHMO ) Group; International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy ( IHIT ) Group . Cost effectiveness of peginterferon alpha‐2b plus ribavirin versus interferon alpha‐2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gut 2003;52:425‐432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sherman KE, Sherman SN, Chenier T, Tsevat J. Health values of patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:2377‐2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chong CA, Gulamhussein A, Heathcote EJ, Lilly L, Sherman M, Naglie G, et al. Health‐state utilities and quality of life in hepatitis C patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:630‐638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Jacobson I, Muir AJ, Pol S, Zeuzem S, et al. Not achieving sustained viral eradication of hepatitis C virus after treatment leads to worsening patient‐reported outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 2020;70:628‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Reddy R, Manns MP, Bourliere M, Gordon SC, et al. Viral eradication is required for sustained improvement of patient‐reported outcomes in patients with hepatitis C. Liver Int 2019;39:54‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bryce CL, Angus DC, Switala J, Roberts MS, Tsevat J. Health status versus utilities of patients with end‐stage liver disease. Qual Life Res 2004;13:773‐782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rathi S, Fagan A, Wade JB, Chopra M, White MB, Ganapathy D, et al. Patient acceptance of lactulose varies between Indian and American cohorts: implications for comparing and designing global hepatic encephalopathy trials. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2018;8:109‐115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arguedas MR, DeLawrence TG, McGuire BM. Influence of hepatic encephalopathy on health‐related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci 2003;48:1622‐1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tapper EB, Konerman M, Murphy S, Sonnenday CJ. Hepatic encephalopathy impacts the predictive value of the Fried Frailty Index. Am J Transplant 2018;18:2566‐2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tapper EB, Baki J, Parikh ND, Lok AS. Frailty, psychoactive medications, and cognitive dysfunction are associated with poor patient‐reported outcomes in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2019;69:1676‐1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCaffrey N, Kaambwa B, Currow DC, Ratcliffe J. Health‐related quality of life measured using the EQ‐5D–5L: South Australian population norms. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;14:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material