Abstract

Targeted inhibition of the c‐Jun N‐terminal kinases (JNKs) has shown therapeutic potential in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA)‐related tumorigenesis. However, the cell‐type‐specific role and mechanisms triggered by JNK in liver parenchymal cells during CCA remain largely unknown. Here, we aimed to investigate the relevance of JNK1 and JNK2 function in hepatocytes in two different models of experimental carcinogenesis, the dethylnitrosamine (DEN) model and in nuclear factor kappa B essential modulator (NEMO)hepatocyte‐specific knockout (Δhepa) mice, focusing on liver damage, cell death, compensatory proliferation, fibrogenesis, and tumor development. Moreover, regulation of essential genes was assessed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, immunoblottings, and immunostainings. Additionally, specific Jnk2 inhibition in hepatocytes of NEMOΔhepa/JNK1Δhepa mice was performed using small interfering (si) RNA (siJnk2) nanodelivery. Finally, active signaling pathways were blocked using specific inhibitors. Compound deletion of Jnk1 and Jnk2 in hepatocytes diminished hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in both the DEN model and in NEMOΔhepa mice but in contrast caused massive proliferation of the biliary ducts. Indeed, Jnk1/2 deficiency in hepatocytes of NEMOΔhepa (NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa) animals caused elevated fibrosis, increased apoptosis, increased compensatory proliferation, and elevated inflammatory cytokines expression but reduced HCC. Furthermore, siJnk2 treatment in NEMOΔhepa/JNK1Δhepa mice recapitulated the phenotype of NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice. Next, we sought to investigate the impact of molecular pathways in response to compound JNK deficiency in NEMOΔhepa mice. We found that NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers exhibited overexpression of the interleukin‐6/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathway in addition to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)‐rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (Raf)‐mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)‐extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK) cascade. The functional relevance was tested by administering lapatinib, which is a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor of erythroblastic oncogene B‐2 (ErbB2) and EGFR signaling, to NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice. Lapatinib effectively inhibited cystogenesis, improved transaminases, and effectively blocked EGFR‐Raf‐MEK‐ERK signaling. Conclusion: We define a novel function of JNK1/2 in cholangiocyte hyperproliferation. This opens new therapeutic avenues devised to inhibit pathways of cholangiocarcinogenesis.

Abbreviations

- α‐SMA

alpha smooth muscle actin

- Δhepa

hepatocyte‐specific knockout

- A6

Notch‐1

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BW

body weight

- CAF

cancer‐associated fibroblast

- CC3

cleaved caspase 3

- CCA

cholangiocarcinoma

- CK

creatine kinase

- CLD

chronic liver disease

- Col1A1

collagen type I alpha 1

- DEN

diethylnitrosamine

- dmbt1

deleted in malignant brain tumors 1

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- ERBB

erythroblastic oncogene B

- ERK

extracellular signal‐regulated kinase

- f/f

floxed mice

- gabrp

gamma‐aminobutyric acid A receptor, pi

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HER

human epidermal growth factor receptor

- HNF

hepatocyte nuclear factor

- HPF

high‐power field

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IL

interleukin

- JAK

Janus kinase

- JNK

c‐Jun N‐terminal kinases

- LoxP

locus of X‐over P1

- LPC

liver parenchymal cell

- LW

liver weight

- MAPK

mitogen‐activated protein kinase

- MEK

mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MUC

mucin

- NEMO

nuclear factor kappa B essential modulator

- NF‐κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- OSM

oncostatin M

- p

phosphorylated

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- qRT‐PCR

quantitative reverse‐transcription polymerase chain reaction

- Raf

rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma

- RIPK

receptor‐interacting serine/threonine‐protein kinase

- si

small interfering

- SOCS3

suppressor of cytokine signaling 3

- SOX‐9

transcription factor SOX 9

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TKI

tyrosine kinase inhibitor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick‐end labeling

Bile duct hyperplasia and aberrant cholangiocyte growth can result in hepatic cystogenesis, differentially diagnosed on the basis of cholangioma, cholangiofibrosis, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), and oval cell hyperplasia.( 1 , 2 ) CCA, a malignancy that arises in the setting of chronic inflammation of biliary epithelium cells, has an increasing incidence and is the second most common primary liver cancer globally. Unfortunately, survival beyond a year of diagnosis is less than 5% and therapeutic options are scarce.( 3 )

Several in vivo and in vitro models as well as research with human tissue samples help to elucidate the main pathways implicated in CCA formation. However, none of these studies recapitulates the human disease, and translation into improved patient outcome has not been achieved. In addition, the pathophysiology of CCA remains poorly understood. Thus, there is an urgent need for new models to improve the management of this insidious and devastating disease.

The c‐Jun N‐terminal kinases (JNKs) are evolutionarily conserved mitogen‐activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and play an important role in converting extracellular stimuli into a wide range of cellular responses, including inflammatory response, stress response, differentiation, and survival.( 4 ) In tumorigenesis, JNK has been shown to have tumor suppressive function in breast,( 5 ) prostate,( 6 ) lung,( 7 ) and pancreas( 8 ) cancer. However, the pro‐oncogenic role for JNK has also been well documented.( 9 , 10 , 11 ) Importantly, JNK has lineage‐determinant functions in liver parenchymal cells (LPCs) where it not only favors proliferation of biliary cells but also directly biases biliary cell‐fate decisions in bipotential hepatic cells. It has been reported that JNK inhibition delays CCA progression( 12 ) by impeding JNK‐mediating biliary proliferation. These data indicate that JNK modulation would be of therapeutic benefit in patients with CCA. Nevertheless, little is known about the cell‐type‐specific role and mechanism of JNK in biliary overgrowth in order to have a targeted and definite therapy against CCA.

In the present study, we investigated the implications of hepatocyte‐defective JNK signaling in experimental carcinogenesis. Unexpectedly, loss of Jnk1/2 in LPCs inhibited hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) but triggered biliary epithelium hyperproliferation and features compatible with CCA. Overall, our data uniformly suggest that hepatocytic JNK is pivotal for biliary epithelial hyperproliferation resulting in ducto/cystogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Mice and Animal Experiments

Albumin (Alb)‐Cre and Jnk2‐deficient mice in a C57BL/6J background were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Jnk1 locus of X‐over P1 (LoxP ) /LoxP/Jnk2 −/− (Hepatocyte‐specific knockout of Jnk1 [JNK1Δhepa]) mice were created as reported.( 13 , 14 , 15 ) We used male mice for all experiments. For in vivo experiments, mice were treated with a daily dose of lapatinib (150 mg/ kg weight; n = 7 mice per group) or vehicle (0.5% hydroxypropylmethylcellulose/1% Tween 80) (n = 6) by oral gavage starting at 6 weeks of age over a period of 6 weeks. For small interfering (si)RNA‐mediated knockdown experiments, 8‐week‐old nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐κB) essential modulator (NEMO)Δhepa/JNK1Δhepa were injected with a dose of 0.2 mg/kg body weight (BW) siJnk2 or small interfering luciferase (siLuc) once per week over a period of 4 weeks. In parallel, lapatinib was given orally to siJnk2‐treated NEMOΔhepa/JNK1Δhepa mice on the same day of the first siJnk2‐ injection. Induction of tumorigenesis was performed by intraperitoneal injection of 25 mg/kg BW of diethylnitrosamine (DEN; Sigma‐Aldrich, Munich, Germany) at 14 days of age. Mice were killed 24 weeks later. Vehicle‐injected (saline) male mice served as controls.

Animal experiments were carried out according to the German legal requirements and animal protection law and approved by the authority for environment conservation and consumer protection of the state of North Rhine‐Westfalia (LANUV; Germany). All strains were crossed on a C57BL/6 background. The mice were housed in the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science at the University Hospital RWTH‐Aachen University according to German legal requirements (Animal Welfare Act [DeutschesTierschutzgesetz], Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations [FELASA], Society of Laboratory Animal Science [GV‐SOLAS]) under a permit of the Veterinäramt der Städteregion Aachen. All animals received humane care according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Animal Models. All organ explants and animal experiments were approved by the local authority for environment conservation and consumer protection of LANUV on the following animal grants: 30034G (AZ‐84‐02.04.2016.A080) and TVA‐11324GZ (AZ‐84‐02.04.2016.A490).

Interference RNA against Jnk2 (siJnk2)

The siRNA molecules were purchased from Axolabs GmbH (Kulmbach, Germany) and were chosen due to their ability to specifically target Jnk2 in mice with mismatches to Jnk1 (2‐18 nucleotides) to increase in vivo stability and suppression of the immune‐stimulatory properties, as described.( 16 )

Data and Software Availability

Affymetrix Microarray was performed as described,( 17 ) and data were deposited with the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE140498.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Student t test or by one‐way ANOVA followed by a Newman‐Keuls multicomparison test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Combined Loss of Jnk1/2 Function in Hepatocytes Triggers Biliary Hyperproliferation and Ducto/Cystogenesis in an Experimental Model of Chronic Liver Disease

Mice lacking NEMO in LPCs spontaneously develop HCC, rendering these animals an ideal model that perfectly mimics progression of chronic liver disease (CLD) as observed in humans.( 18 ) We previously established that Jnk1 and Jnk2 have specific roles for the progression of NEMO∆hepa‐dependent chronic liver injury, indicating that the MAPK genes expressed in liver cells have pivotal functions in cell death and inflammation.( 19 ) We then found that combined activities of Jnk1 and Jnk2 specifically in hepatocytes protected against toxic liver injury (CCl4 and acetaminophen).( 15 ) However, Jnk1/2 deficiency in hepatocytes increased tumor burden in an experimental model of HCC.( 10 ) Therefore, in the present study we aimed to investigate the definitive contribution of JNK genes to liver cancer.

For this purpose, we generated NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa and their respective controls NEMO∆hepa and NEMOfloxed (f/f) mice (Supporting Fig. S1) and examined the progression of liver disease. At 13 weeks of age, histologic evaluation of NEMO∆hepa unveiled the presence of dysplastic nodules, steatohepatitis, and cell death (Supporting Fig. S2A,B). All NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers with no external signs of nodules spontaneously showed hyperproliferation of biliary epithelium translated into hepatic ducto/cystogenesis and lymphoid aggregates surrounding these structures (Supporting Fig. S2A,B).

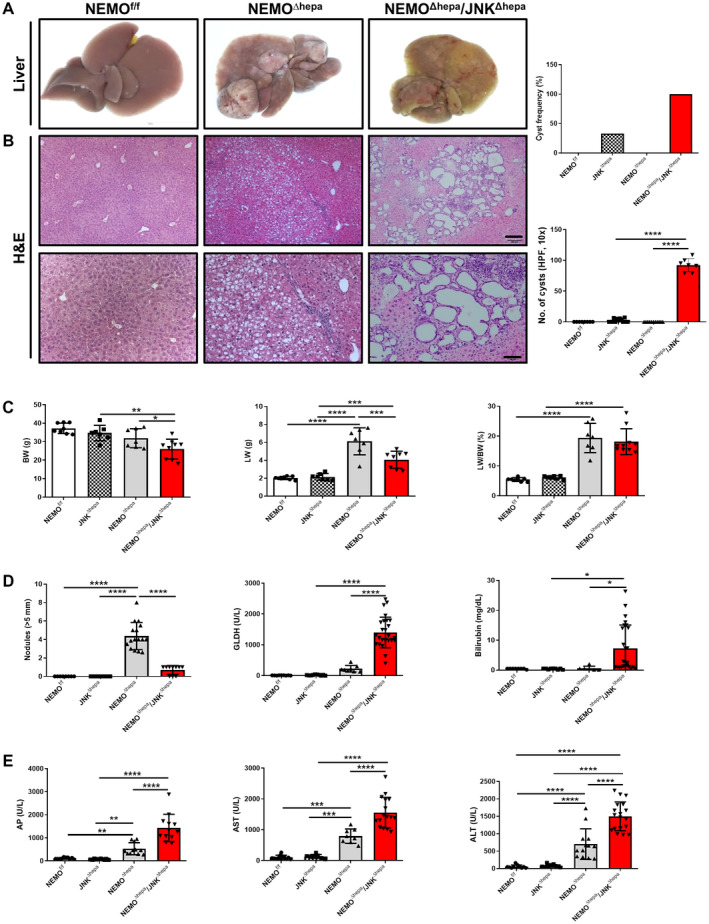

Development of HCC is characteristic of 1‐year‐old NEMOΔhepa mice, visible both macroscopically and histologically. However, most 52‐week‐old NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice displayed no signs of HCC. Here, yellowish coloration of the liver parenchyma was associated with hyperproliferation of biliary epithelial cells and lymphoid cell accumulation. This was much more pronounced than at earlier stages of CLD. Interestingly, histopathological examination of these specimens in two different institutes (Utrecht and Graz) revealed that approximately 33% of 52‐week‐old JNKΔhepa livers presented small cysts while an increased frequency and a higher number of ductular cells were evident in the hepatic parenchyma of all NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa, with atypia compatible with CCA (Fig. 1A,B; Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Deletion of Jnk1/2 in 52‐week‐old NEMOΔhepa livers triggers cyst formation. (A) Macroscopic view of livers from 52‐week‐old NEMOf/f (wild type), NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice. (B) Representative H&E staining of liver sections of NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers at 52 weeks of age. Different magnifications were used (left). Scale bar 200 µm. Cyst frequency and number of visible microscopic cysts per 10× view field were calculated and graphed (right), magnification is 10× for upper and magnification is 20× for lower. (C) BW (left); LW (center); LW/BW ratio (right). (D) Tumor burden for each individual mouse was characterized by calculating total number of visible tumors >5 mm in diameter per mouse (left); serum levels of GLDH (center); bilirubin (right). (E) Serum levels of AP (left), AST (center), and ALT (right), in 52‐week‐old NEMOf/f, JNKΔhepa, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Abbreviations: AP, alkaline phosphatase; GLDH, glutamate dehydrogenase; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Table 1.

Histopathological Characteristics of the Different Mouse Groups (Scale, 0‐4)

| NEMO∆hepa | NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa | |

|---|---|---|

| Neoplasia | HCC | Cystic cholangioma Mucinous CCA |

| Anisokaryosis | 3.5 | 2.0 |

| Altered foci | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Mitosis/HPF (40×) | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| Cellular hypertrophy | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Dysplasia | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Oval cell proliferation | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Portal inflammation | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Overall inflammation | 3.0 | 3.5 |

| Ductular reaction | 1.5 | 2.0 |

| Apoptosis | 1.0 | 3.0 |

| Fibrosis | 3.0 | 4.0 |

| Steatosis | 1.4 | 0.0 |

| Others | Pale cytoplasm hepatocytes | Massive bile duct proliferation |

Moreover, combined JNK1/JNK2 deletion in hepatocytes of NEMO∆hepa mice triggered significantly reduced BW and liver weight (LW) compared with NEMO∆hepa mice but a similar LW/BW ratio as hepatocyte‐specific NEMO‐deficient mice (Fig. 1C). Notably, at 13 weeks of age, NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa animals had a significantly increased hepatosomatic ratio compared with NEMO∆hepa mice, albeit no differences in BW or LW (Supporting Fig. S2C).

Surprisingly, 1 year‐old NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers exhibited reduced HCC compared with NEMO∆hepa animals (Fig. 1D). In contrast, JNK1/2‐deleted NEMO mice displayed ducto/cystogenesis that was much more pronounced than at earlier stages of CLD (Fig. 1B; Supporting Fig. S2D). NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers exhibited significantly elevated glutamate dehydrogenase, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels compared with NEMO∆hepa mice, already detectable at 13 weeks (Fig. 1D,E; Supporting Fig. S2D,E). Altogether, these data indicated that deletion of Jnk1/2 in an experimental model of CLD has pivotal implications in cell death, cholestasis development, and ductular proliferation of cholangiocytes.

Analysis of the Microenvironment Driving Massive Bile Duct Proliferation in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa Animals

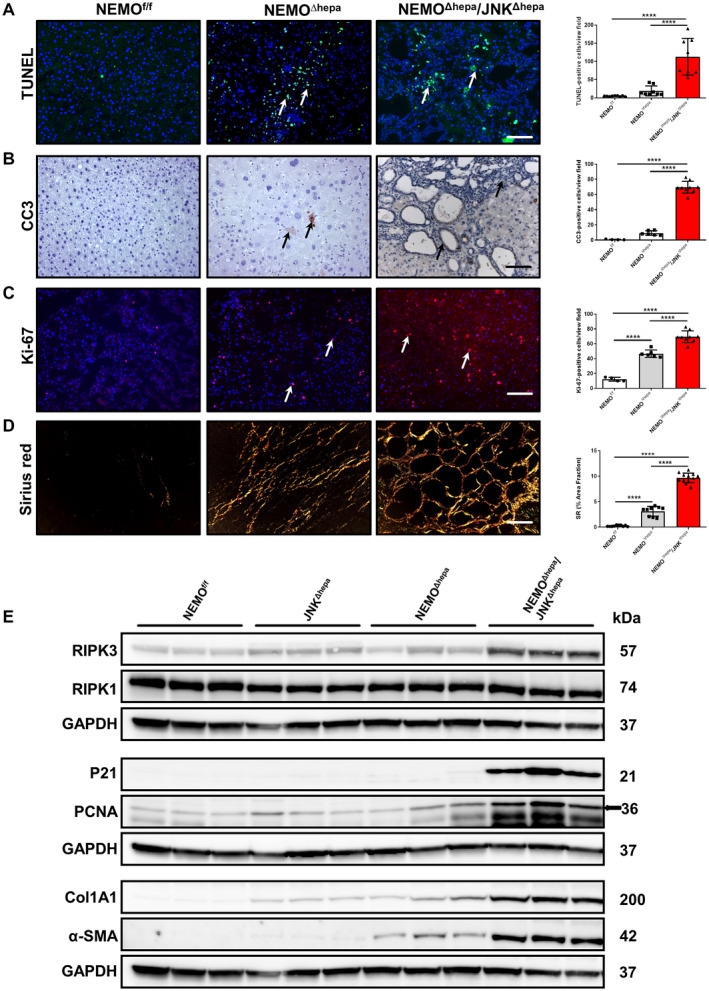

Lack of NF‐κB activity in hepatocytes triggers spontaneous HCC. In turn, 52‐week‐old NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice displayed significantly increased bile duct proliferation. We next investigated liver damage associated with the phenotype of these animals. We first applied terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick‐end labeling (TUNEL) staining, which detects several types of cell death, including necrosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis.( 20 ) NEMO∆hepa livers displayed a high percentage of TUNEL‐positive cells, while NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers showed significantly increased levels of cell death (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of cell death, cell proliferation, and collagen deposition in 52‐week‐old NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice. (A) Representative TUNEL staining of liver sections of NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers at 52 weeks of age (left). TUNEL‐positive cells were quantified and graphed (right). (B) Representative IHC staining for CC3 of the same livers (left). CC3‐positive cells were quantified and graphed (right). (C) Immunofluorescent staining for Ki‐67 of liver cryosections from the same livers (left). Ki‐67‐positive cells were quantified and graphed (right). (D) Representative sirius red staining of paraffin sections from the indicated genotypes (left). Quantification of the positive sirius red area fraction was performed with Image J and graphed (right). (A‐D) Scale bars, 200 μm. Arrows (→) indicate positive cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; ****P < 0.0001. (E) Protein levels of α‐SMA, Col1A1, PCNA, p21, RIPK1, and RIPK3 from whole‐liver extracts of 52‐week‐old NEMOf/f, JNKΔhepa, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice were analyzed by western blot with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Apoptosis and necroptosis are two relevant forms of cell death in the pathogenesis of human and murine liver disease.( 21 , 22 ) To discriminate between these two types of cell death, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) analyses, which revealed significantly higher levels of the apoptosis marker cleaved caspase 3 (CC3) in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers, especially in cholangiocytes but also in immune infiltrates of these livers (Fig. 2B). We subsequently studied proteins involved in necroptosis, e.g., receptor‐interacting serine/threonine‐protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) by western blot and IHC, which was found overexpressed in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers, while no difference in RIPK1 protein expression was found (Fig. 2E; Supporting Fig. S3A).

Cell‐cycle dysregulation is characteristic of biliary overgrowth, resulting in CCA. Increased Ki‐67‐positive and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)‐positive cells were observed in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa frozen and paraffin sections, respectively, the latter further confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2C,E; Supporting Fig. S3B). Moreover, the number of transcripts for PCNA and cyclin D1 was up‐regulated in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers (Supporting Fig. S3C). P21 has been shown to induce cell‐cycle arrest and promote the DNA repair gene, thus acting as a tumor suppressor.( 23 , 24 ) Interestingly, we observed p21 overexpression in Jnk1/2‐deficient NEMO∆hepa mice (Fig. 3E). Moreover, oxidative stress in the liver microenvironment has a definitive role in CCA development. We thus measured lipid peroxidation and the antioxidant defense of these animals. Interestingly, strong 4‐hydroxynonena immunostaining and catalase depletion (Supporting Fig. S3D,E) in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers confirmed elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production associated with cholangiocellular proliferation.

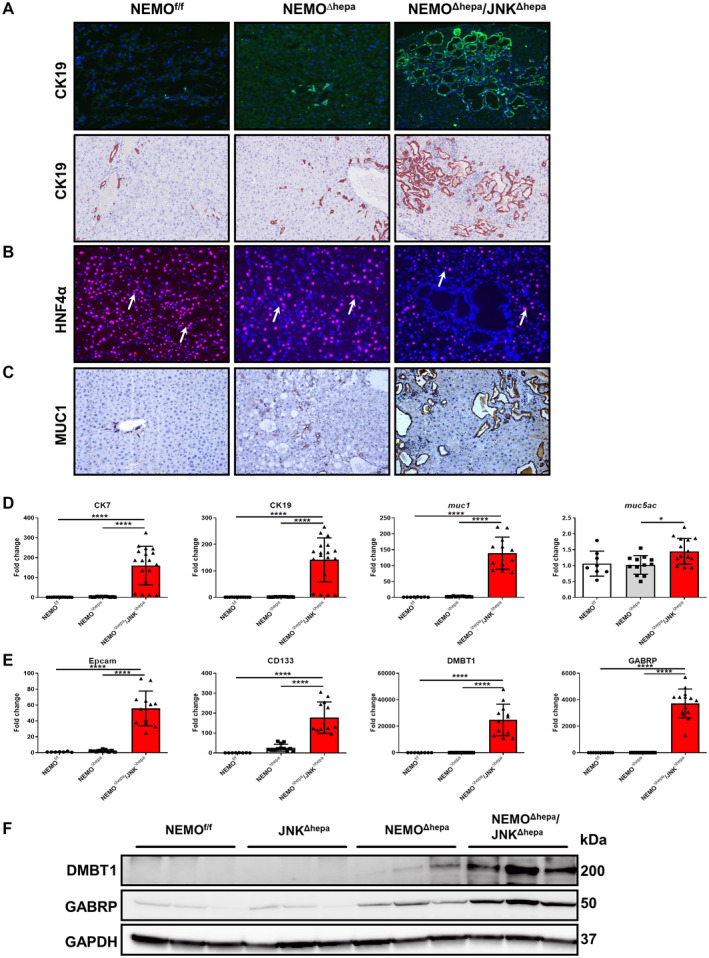

Fig. 3.

Loss of Jnk1/2 in NEMOΔhepa hepatocytes triggers cholangiocellular proliferation. (A) Representative IF for CK19 of liver cryosections was performed in 52‐week‐old NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers (upper panel). IHC staining for CK19 reveals densely packed cholangiocellular proliferates with a tubular growth pattern mimicking morphologic features of well‐differentiated human CCA (lower panel), magnification is 20×. (B) Representative IF staining for HNF‐4α of the same livers, magnification is 20×. (C) Representative IHC staining for Muc1, magnification is 20×. (D) mRNA expression analysis of CK7 (left), CK19, and muc1 (center) and muc5ac (right) was quantified by qRT‐PCR in the same livers. (E) mRNA expression analysis of Epcam (left), CD133 and DMBT1 (center), and GABRP (right) was quantified by qRT‐PCR of samples taken from NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers killed at 52 weeks. (F) Protein expressions of GABRP and DMBT1 from whole‐liver extracts of 52‐week‐old NEMOf/f, JNKΔhepa, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice were analyzed by western blot with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH served as loading control. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001. Abbreviations: CD, cluster of differentiation; Epcam, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; IF, immunofluorescence.

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are important cells shaping the hepatic microenvironment after liver damage. Hence, HSCs are involved in the high number of α‐smooth muscle actin (α‐SMA)‐positive myofibroblasts and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition associated with CCA development.( 25 ) Sirius red staining and quantification confirmed strong collagen deposition in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers (Fig. 2D; Supporting Fig. S4A). Furthermore, collagen type I alpha 1 (Col1A1) and α‐SMA were dramatically overexpressed in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa liver protein lysates (Fig. 2E) and were associated with significantly increased transcripts of col IA1, matrix metalloproteinase (mmp)7/9/12, and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (timp)1 (Supporting Fig. S4B,C). Cytokine‐mediated tissue fibrosis was also measured, and levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (mcp1), tumor necrosis factor (tnf), interleukin (il)1β, and regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed, and secreted (rantes) were significantly up‐regulated in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice (Supporting Fig. S4D,E). Altogether, these data suggest that fibrogenesis and unresolved inflammation are involved in CCA development in the NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa context while HCC‐related tumorigenesis is diminished as confirmed by low glutamine synthase expression (Supporting Fig. S5A).

NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa Livers Exhibit Typical Features of Human CCA

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that many ductules were composed of creatine kinase (CK)19‐positive cells. In fact, NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa cystic and CCA‐like structures exhibited CK19‐positive staining that was corroborated by dramatically elevated CK7/19 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in these livers (Fig. 3A,D). NEMOf/f had regular small bile ducts, and NEMO∆hepa exhibited mild to moderate ductular proliferates similar to a ductular reaction in humans. Noticeably, livers of NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice displayed cholangiocellular proliferates with a tubular architecture resembling the morphology of human well‐differentiated CCA, highlighted by a strong‐positive CK19 signal. In contrast, hepatocyte nuclear factor (HNF)‐4α staining was characteristic of pericystic areas and hepatocytes of NEMO∆hepa and NEMOf/f livers (Fig. 3B). Cells containing cytoplasmic mucin (MUC) granules are common in CCA tissues.( 26 ) Thus, we assessed the expression of MUC1 and MUC5AC, which are closely related to dedifferentiation, infiltrative growth pattern, and patient survival.( 26 ) Whereas MUC1 staining was limited to areas of ductogenesis or oval cell reaction in NEMO∆hepa livers, it was very strong in cysts of NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers, which were associated with significantly increased muc1 and muc5ac mRNA levels in these mice (Fig. 3C,D).

High expression of cholangiocyte markers, including cluster of differentiation (cd)133 and expression of CCA/tumor‐enriched markers, including epithelial cell adhesion molecule (epcam), deleted in malignant brain tumors 1 (dmbt1), and gamma‐aminobutyric acid A receptor, pi (gabrp),( 27 ) together with the accumulation of transcription factor SOX 9 (SOX‐9)‐positive cells (Fig. 3E,F; Supporting Fig. S5B) suggest that loss of Jnk1/2 function in hepatocytes promotes the shift from HCC to CCA in this experimental model of CLD.

Administration of DEN to JNKΔhepa Mice Triggers Hepatic Ducto/Cystogenesis Without Hepatocarcinogenesis

To validate the relevance of Jnk1/2 in mediating the shift from HCC to CCA, we applied a second model of carcinogenesis, the DEN model. Previously, Das and colleagues,( 10 ) using mice with compound deficiency of Jnk1/2 in hepatocytes, demonstrated that the JNK genes possess tumor‐suppressing roles in liver carcinogenesis that depend on the cell types of the liver. Additionally, we showed that hepatocyte‐specific Jnk1/2 knockout female and male mice have no phenotype affecting the correct function of the liver.( 15 ) These previous results are confirmed in the present study in a larger pool of animals ranging from 13 to 52 weeks of age (Supporting Figs. S6A‐D and S7A‐D). However, approximately 33% of these mice from week 30 of age histologically displayed tumors resembling human CCA in their liver parenchyma that did not affect liver function (Fig. 1A,B; Supporting Fig. S7A‐D).

JNKΔhepa mice were challenged with the carcinogen DEN. Interestingly, these mice exhibited jaundice and the liver was yellowish albeit with decreased tumor load (Supporting Fig. S8A). The LW/BW ratio was significantly decreased in JNKΔhepa compared with JNKf/f mice (Supporting Fig. S8B). Histologic evaluation performed by two blinded pathologists demonstrated the presence of cystogenesis and cholangioma‐like structures in liver parenchyma accompanied by strong infiltration of immune cells (Fig. S8C). The analysis of serum transaminases in JNKΔhepa demonstrated decreased ALT and AST levels in these animals (Fig. S8D,E). These results indicated that JNK1 and JNK2 might influence cell fate during liver tumorigenesis.

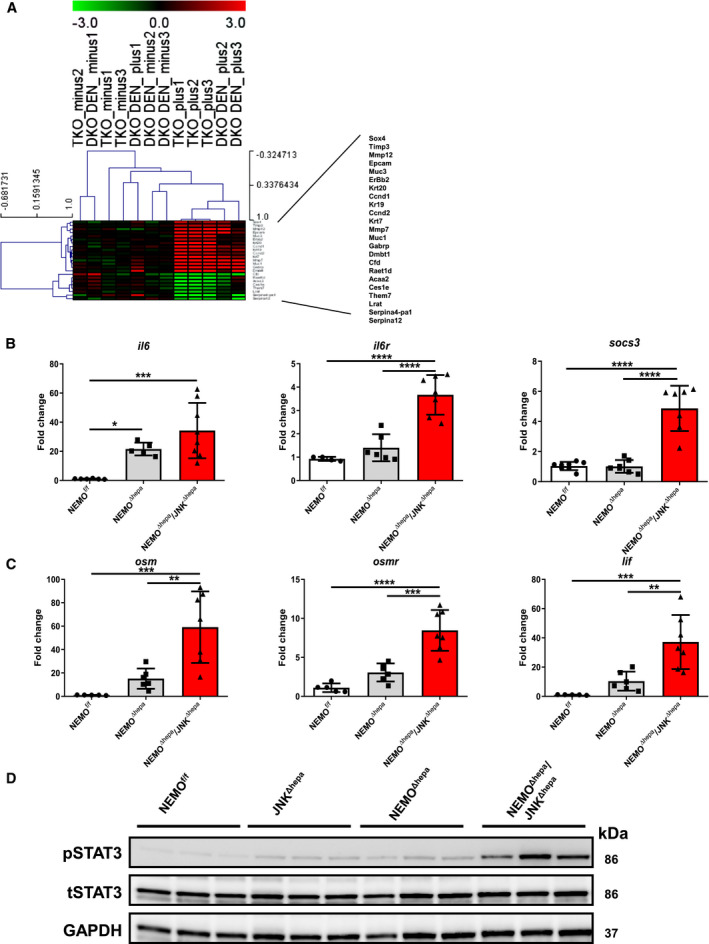

To further analyze the differences between both animal models, age progression versus chemically induced HCC, we performed a microarray analysis (Supporting Fig. S9A,B). Interestingly, dmbt1, muc1, gabrp, and immunoglobulin heavy chain (gamma polypeptide) (ighg)2b were commonly up‐regulated in Jnk1/2‐deficient NEMO∆hepa mice and Jnk1/2‐deficient mice challenged with DEN, indicating that epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) might be modulated through a JNK‐dependent mechanism.

Next, we analyzed total common up‐regulated and down‐regulated genes in NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa versus JNKΔhepa + DEN, which were the majority compared to specific changes of each experimental model (Supporting Fig. S9C,D). Heat map analysis of these genes showed up‐regulation of genes related to CCA, like dmbt1, muc1, gabrp, and matrix deposition, including timp1 and mmp12, and down‐regulation of serpines, which are often implicated in HCC development (Fig. 4A). Altogether, these data reinforce the notion that the JNK signaling pathway modulates cell fate during liver carcinogenesis.

Fig. 4.

The IL‐6/STAT3 pathway is pivotal in biliary cell proliferation during liver carcinogenesis. (A) Gene array analysis was performed in 8‐week‐old NEMOΔhepa/JNKf/f and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers in addition to 26‐week‐old wild type and JNKf/f and JNKΔhepa livers challenged with DEN. Correlation of the fold induction of gene expression in liver is shown. Log2 expression values of the individual mice were divided by the mean of the NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice. Log ratios were saved in a .txt file and analyzed with the Multiple Experiment Viewer. Top up‐regulated and down‐regulated target substrates are shown (red, up‐regulated; green, down‐regulated; n = 3, 3.0< fold change >3.0). (B) mRNA expression analysis of il6 (left); il6r (center), and socs3 (right). (C) mRNA expression analysis of osm (left), osmr (center), and lif (right) was quantified by qRT‐PCR of samples taken from NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers killed at 52 weeks. (D) Protein expression levels of STAT3 and pSTAT3 from whole‐liver extracts of 52‐week‐old NEMOf/f, JNKΔhepa, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice were analyzed by western blot with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH served as loading control. Abbreviations: DKO, JNK1f/f/JNK2−/− + DEN; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; osmr, oncostatin M receptor; TKO, NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa.

Overexpression of the IL‐6/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 Pathway is Characteristic for NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa Livers

Cytokines play an important role during carcinogenesis by shaping the inflammatory microenvironment toward malignant transformation. In particular, IL‐6 has been demonstrated to have an integral role in CCA biology and other cancers as a growth and survival factor.( 28 ) Under physiologic conditions, IL‐6 through a Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 pathway induces expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), accelerating inflammation, cell growth, and tumor formation. We found overexpression of il6, il6 receptor (il6r), and socs3 mRNA as well as other IL‐6 family members, including LIF IL‐6 family cytokine (lif) and oncostatin M (osm) (Fig. 4B,C; Supporting Fig. S10A). OSM has recently been identified as an important regulator of the EMT/cancer stem cell plasticity program that promotes tumorigenic properties.( 29 ) Osm was significantly increased in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers.

Concomitantly, high phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) levels were evident in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa compared with NEMO∆hepa livers (Fig. 4D; Supporting Fig. S10B), indicating that this pathway is strongly activated in our murine model.

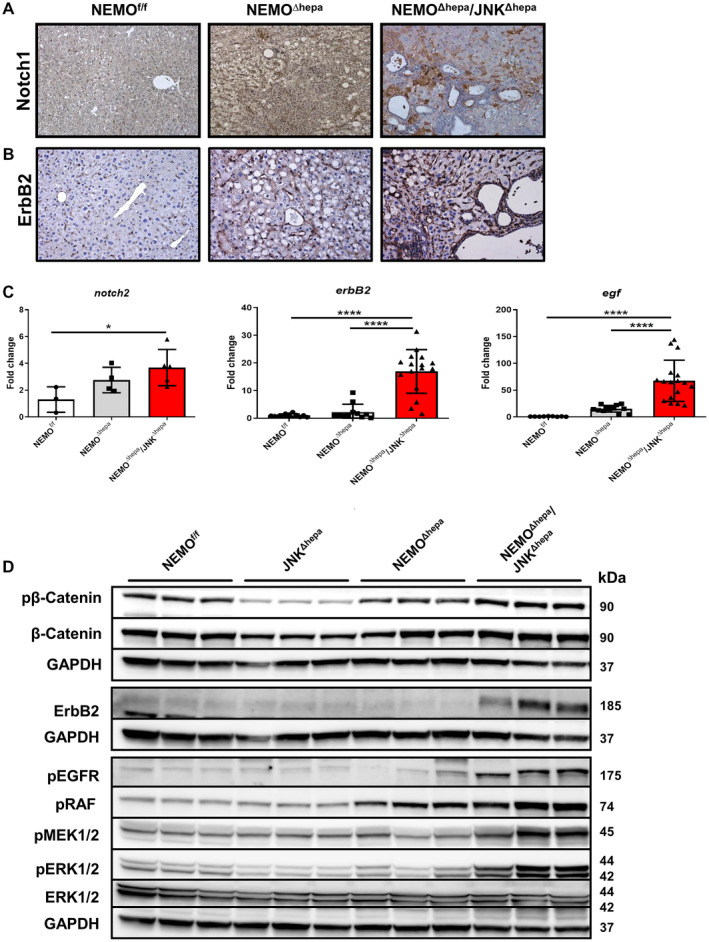

The EGF‐Raf‐MEK‐ERK1/2 Pathway is Overexpressed in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa Animals

Activation of Notch and Wnt signaling pathways stimulates proliferation of the hepatic progenitor cell compartment. In particular, NOTCH signaling is implicated in the commitment toward the cholangiocyte fate, while WNT can trigger differentiation toward the hepatocyte lineage.( 30 ) Therefore, we first assessed the relevance of Notch‐1 (A6) in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers. Interestingly, A6 staining was positive in clusters of immune cells in NEMO∆hepa livers. NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers exhibited increased Notch‐1 expression throughout the liver parenchyma (Fig. 5A). In fact, other family members, including Notch2, were significantly up‐regulated or had a tendency toward increased mRNA levels in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers (Fig. 5C; Supporting Fig. S11A‐F). However, no differences in β‐catenin expression between NEMO∆hepa and NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers were observed (Fig. 5D). Of note, JNK1/2‐knockout mice had reduced phosphorylation of β‐catenin, indicating that JNK is necessary for β‐catenin phosphorylation, as suggested.( 31 )

Fig. 5.

Activation of EGF‐EGFR‐RAF‐MEK1/2‐ERK1/2 is distinctive of NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice. (A) Representative IHC for NOTCH‐1 staining of liver sections of 52‐week‐old NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers, magnification is 20×. (B) Representative IHC for ErbB2 staining of liver sections of the same livers. (C) mRNA expression analysis of notch‐2 (left), erbB2 (center), and egf (right) was quantified by qRT‐PCR of samples taken from NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice killed at 52 weeks. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001. (D) Protein expressions of phospho‐β‐catenin, β‐catenin, ErbB2, phospho‐EGFR, phospho‐RAF, phospho‐MEK1/2, phospho‐ERK1/2, and total ERK1/2 from whole‐liver extracts of 52‐week‐old NEMOf/f, JNK1Δhepa/JNK2−/−, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice were analyzed by western blot with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH served as loading control. Abbreviation: phospho, phosphorylated.

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family includes erythroblastic oncogene B (ERBB)1, 2, 3, and 4, with ERBB1/EGFR and ERBB2/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (Neu in rodents) being frequently implicated in the multistep carcinogenesis of CCA.( 32 ) Specifically, HER2 is a well‐described predictive biomarker for positive anti‐HER2 therapy response in breast and gastric cancer and, lately, in CCA.( 33 , 34 ) Our first results showed dramatically increased ErbB2 protein and mRNA levels in livers of NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa compared with NEMO∆hepa hepatic tissue (Fig. 5B‐D). Interestingly, we also found increased expression of the EGFR ligand egf (Fig. 5C). Consistently, the levels of EGFR phosphorylation (pEGFR) were markedly elevated in the livers of NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice (Fig. 5D).

The rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF)‐mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)‐extracellular signal‐regulated kinase (ERK) transduction pathway is a key signaling cascade that regulates cellular proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis and is frequently dysregulated in HCC( 35 ) and in biliary tract cancer.( 36 ) Binding of EGF to EGFR triggers its tyrosine kinase activity downstream signaling leading to the end phosphorylation of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2, with translocation of ERK to the nucleus and expression of genes related to proliferation. Increased phosphorylation (i.e., activation) of RAF, MEK1/2, and ERK/2 was found in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice (Fig. 5D) associated with biliary overgrowth. These results were further corroborated in livers of 13‐week‐old mice (Supporting Fig. S12), indicating that the RAF‐MEK‐ERK pathway was constitutively activated at early stages of cholangiocarcinogenesis.

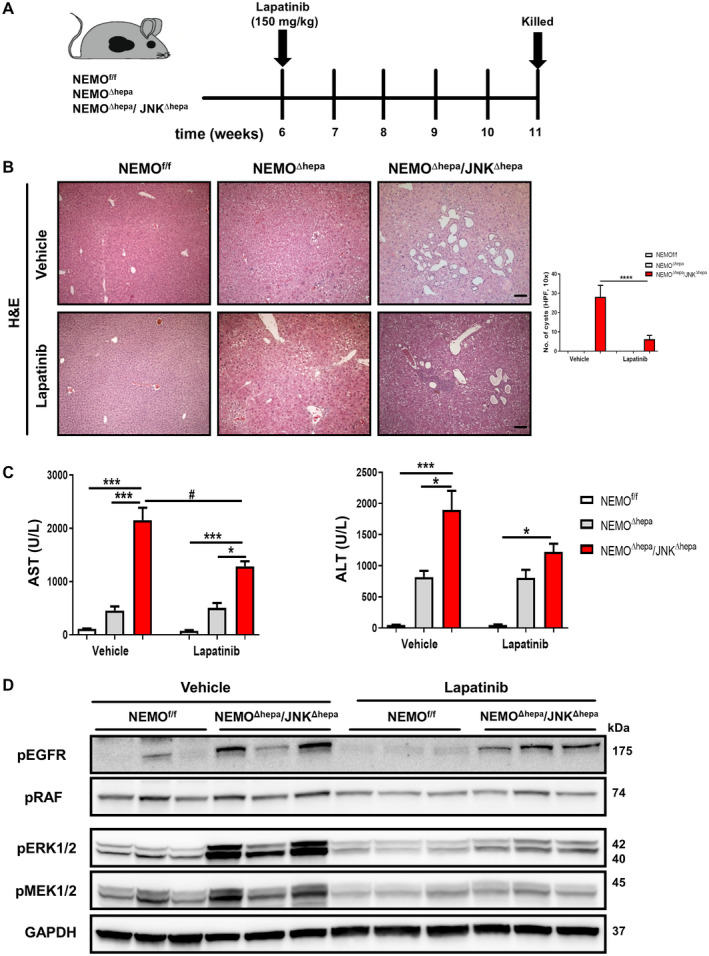

Lapatinib Treatment Prevents Biliary Expansion and Ducto/Cystogenesis in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa Mice

Our data strongly indicate the EGFR‐HER2 pathway being involved in biliary cell hypergrowth and cholangiocarcinogenesis in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers. Lapatinib is a dual EGFR2/HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) targeting both EGFR and HER2.( 37 , 38 ) It successfully inhibited the growth of HER‐overexpressing breast cancer cells in culture and in tumor xenografts.( 39 ) Taking into consideration the promising therapeutic option of lapatinib, we subsequently explored the potential beneficial effect of this dual TKI in our model of cholangiocellular proliferation.

Lapatinib was administered daily by oral gavage for 6 weeks in NEMOf/f, NEMO∆hepa, and NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice (Fig. 6A). The TKI did not cause any relevant histopathological or serum biochemistry alterations to NEMOf/f or NEMO∆hepa animals (Fig. 6B). However, lapatinib treatment of NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice resulted in a significant reduction of cyst‐like structures (Fig. 6B). Lapatinib also significantly reduced serum AST and ALT levels in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa compared with NEMOf/f and NEMO∆hepa animals (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Lapatinib, a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor, protects against hyperbiliary proliferation in 52‐week‐old NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa animals. (A) Experimental design of lapatinib (150 mg/kg BW) or vehicle administration to 6‐week‐old NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice. (B) Representative H&E staining of liver sections of NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa livers treated with either vehicle or lapatinib for 6 weeks (left), magnification is 10×. Number of visible microscopic cysts per 10× view field were calculated and graphed (right). (C) Serum levels of AST and ALT, in NEMOf/f, NEMOΔhepa, and NEMOΔhepa/JNKΔhepa mice after 6 weeks of lapatinib treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, # P < 0.05 (intergroup). (D) Levels of phospho‐ERK1/2, phospho‐MEK1/2, phospho‐RAF, and phospho‐EGFR from whole‐liver extracts of the indicated genotypes treated with vehicle or lapatinib were analyzed by western blot with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH served as loading control. Abbreviations: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; phospho, phosphorylated.

Next, the impact of lapatinib on EGFR/HER2 signaling was tested by investigating the downstream RAF‐MEK‐ERK pathway below EGFR/HER2. Decreased activation of EGFR and abrogation of RAF, MEK, and ERK signaling pathways were found in lapatinib‐treated livers compared with vehicle‐administrated NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that lapatinib successfully decreases EGFR‐HER2 signaling and functionally links inhibition of this pathway with biliary overgrowth in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers.

Combined JNK1/JNK2 Deletion is Essential for Hyperproliferation of Bile Ducts

Our data were generated in global JNK2−/− mice. Hence, we aimed to distinguish if hepatocytic or nonparenchymal JNK2 function is essential to direct bile duct proliferation. We applied our recently developed hepatocyte‐specific Jnk2 siRNA (siJnk2) protocol using lipid nanoparticles( 16 ); siLuc served as controls. We included 6‐ to 8‐week‐old untreated floxed NEMOf/f/JNKf/f, siLuc‐treated NEMO∆hepa/JNK1Δhepa, and siJnk2‐challenged NEMO∆hepa/JNK1Δhepa mice in this analysis. In parallel, animals were treated with vehicle or lapatinib.

Interestingly, Jnk2 knockdown in hepatocytes triggered massive biliary cyst formation in livers of vehicle‐treated NEMO∆hepa/JNK1Δhepa animals compared with siLuc‐NEMO∆hepa/JNK1Δhepa and untreated floxed NEMOf/f/JNKf/f mice (Supporting Fig. S13A). These results demonstrate that combined Jnk1/2 deletion in hepatocytes is responsible for directing biliary hyperproliferation in this model. Additionally, lapatinib treatment successfully reduced liver cystogenesis and significantly ameliorated serum transaminases in NEMO∆hepa/JNK1Δhepa + siJnk2 livers, confirming the efficacy of this TKI in experimental biliary cystogenesis (Supporting Fig. S13B‐D).

Discussion

Hyperplasia of the biliary epithelia with variable atypia in cystic bile ducts may give rise to malignant transformation leading to intrahepatic CCA for which an enormous unmet clinical and research need exists. CCA is an epithelial neoplasm derived from primary and secondary bile tracts and accounts for 5%‐10% of primary liver cancer, the incidence and mortality of which are steadily increasing. The 5‐year survival of patients with CCA remains unacceptably low, and survival has not dramatically improved in the past 20 years.( 40 ) This is in part due to a lack of understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying CCA. Because biliary tract cancer is often diagnosed late, the success of the only curative procedure (surgical resection) is limited, and the lack of biomarkers or diagnostic tools that would lead to early diagnosis is a matter of concern.( 41 )

A recent study( 12 ) opened a Pandora´s box for therapeutic options targeting the JNK signaling pathway, a major regulator of cell proliferation, against CCA. Earlier, several studies confirmed the critical role of the JNK signaling pathway in liver cancer.( 10 , 19 , 42 , 43 , 44 ) At present, little is known on the role of JNK in directing differentiation of LPCs and more specifically of bipotential hepatic cells not only in liver homeostasis but also following liver injury.

We first focused on the specific roles of the Jnk genes in the progression of experimental chronic liver disease using NEMO mice and showed how Jnk1 or Jnk2 tipped the balance toward HCC or necroinflammation, respectively.( 19 ) We later demonstrated that combined Jnk1/2 deletion in hepatocytes triggers more severe liver injury, inflammation, and progression after toxic liver injury.( 15 )

Thus, we next sought to investigate the consequences of hepatocytic Jnk1/2 ablation in liver parenchymal proliferation and growth in experimental HCC. For this purpose, we generated NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa mice, which displayed reduced tumor burden, despite the fact that they had signs of jaundice and hyperbilirubinemia, compared to NEMO‐deficient mice developing HCC.( 18 ) Remarkably, Jnk1/2‐deleted NEMO∆hepa livers exhibited hyperproliferation of the biliary epithelium, forming cyst‐like structures compatible with cholangioma or malignant CCA, as assessed by two independent pathologists (Table 1).

These livers were characterized by cell death, inflammatory microenvironment, and ECM deposition. Necroptosis‐associated hepatic cytokine microenvironment induces the shift from HCC to CCA development.( 22 ) NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers display considerable CC3 staining and RIPK3 protein levels, triggering exacerbated compensatory proliferation of LPCs, which are associated with increased ROS production and failure of the antioxidant defense.

Moreover, deposition of ECM and periductural/pericystic scar formation was a prominent feature in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers. A unique characteristic of CCA is the presence of cancer‐associated fibroblasts (CAFs) surrounded by numerous immune cells.( 41 ) CAFs promote the secretion of chemokines/cytokines including EGF in CCA cell lines.( 45 ) Moreover, TNF might be another important culprit in CCA development, as suggested.( 12 )

In parallel with proliferating hepatocytes and a marked expansion of the biliary epithelium, the liver parenchyma of NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa animals was positive for CK19 and SOX‐9 and negative for HNF‐4α. Moreover, we found increased expression of mucin genes. Considering that CCA tissues are characterized by the presence of mucin‐secreting cells, this finding further supports the CCA diagnosis.( 46 ) Interestingly, analysis of gene expression showed the occurrence of CCA/epithelial‐transformed neoplasia‐enriched markers, including Dmbt1 and Gabrp, not only in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa liver but also in a second model of liver carcinogenesis, the DEN model. Confirmation in the two models suggests that CCA development relies on Jnk1/2 combined function in hepatocytes but is independent of NF‐κB activity in LPCs. Moreover, microarray studies highlighted the pivotal role of Jnk1/2 in modulating cell fate by promoting hepatocarcinogenesis and under‐regulating cascades linked with cholangiocarcinogenesis. Our data undoubtedly indicate that loss of Jnk1/2 function promoted CCA in both experimental CLD and chemically induced HCC.

Jnk1/2‐deleted NEMO livers exhibited strong expression of NOTCH‐1/A6 and Notch‐2 and a clear tendency toward increased expression of Notch signaling pathway effectors. These results are consistent with evidence from mouse studies, suggesting that NOTCH and WNT/β‐catenin are key drivers of CCA development. Specifically, NOTCH‐1, ‐2, and ‐3 were shown to be overexpressed in human cholangiocellular injury.( 47 ) In contrast, no differences in β‐catenin expression between NEMO∆hepa and NEMO∆hepa/JNK∆hepa were observed, indicating that hepatocyte differentiation in our model is inhibited in favor of ductular reaction and cholangiocyte differentiation. Of note, JNK1/2‐knockout mice have reduced phosphorylation of β‐catenin, suggesting that JNK is necessary for β‐catenin phosphorylation, as suggested.( 31 )

Our protein and mRNA data overwhelmingly indicated that overexpression and activation of the EGFR/ErbB2 family was implicated in multistep cystogenesis toward CCA in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers. Indeed, EGFR overexpression occurs in 11%‐27% of human CCA, whereas HER2 overexpression is less frequent but very characteristic in transgenic mouse models.( 36 , 48 ) It has been reported that EGF is released by tumor‐associated macrophages (TAM).( 49 ) Binding of EGF to its receptors induces their homodimerization or heterodimerization, which in turn activates downstream signaling pathways that regulate cell differentiation, migration, angiogenesis, and survival.( 50 ) In our study, we specifically focused on RAF‐MEK1/2‐ERK2 and JAK/STAT signaling. Both pathways were dramatically induced in NEMO∆hepa/JNKΔhepa livers, suggestive of the strong proliferative and inflammatory microenvironment within the hepatic parenchyma.

Therefore, we tested the possibility of blocking EGFR/HER2 signaling as a novel strategy in treating hyperproliferation of the biliary epithelium. We used lapatinib, a dual TKI that efficiently inhibits both EGFR and HER2. Treatment not only prevented RAF‐MEK‐ERK activation but also inhibited biliary cyst formation. However, its efficacy in clinical translation may highly depend on enrollment of patients with EGFR/HER2 hyperactivation or overexpression.

Recently, Heikenwalder’s group showed the therapeutic relevance of inhibiting JNK in CCA both in vivo and in cell lines.( 12 ) LPC‐specific Jnk1/2 knockout mice were used in two different CCA models. In contrast to our observations, they found reduced cholangiocellular injury in both models. This apparent discrepancy between both studies may be reconciled considering that adeno‐associated virus‐mediated Cre expression in hepatocytes might not exactly resemble Alb‐Cre excision since birth, as employed in our study. To further confirm the implications of Jnk1/2 ablation in hepatocytes, we blocked Jnk2 specifically in hepatocytes using a liposome‐delivery system coupled to an siRNA that was recently reported by our laboratory.( 16 ) Our data undoubtedly indicated that Jnk1/2 in hepatocytes prevents biliary cell hyperproliferation. In addition, lapatinib successfully prevented activation of the EGFR‐RAF‐MEK1/2‐ERK1/2 pathway in Jnk1/2 mice. However, more studies (e.g, assessment of JNK levels in vitro and in organoids) need to be performed to better define the specific role of JNK for CCA initiation.

Overall, our results show that complete inhibition of JNK signaling in hepatocytes in an experimental HCC model triggers binding of EGF (most likely released by the increased TAM‐derived environment) to its receptor activating EGFR‐RAF‐MEK1/2‐ERK1/2 signaling. This cascade is essential to drive EMT transdifferentiation of oval cells into biliary cells and massive ducto/cystogenesis, which shares the molecular features of CCA. Here, CAF‐derived cytokines, including tnf or transforming growth factor beta (tgfβ), might further contribute to exacerbated proliferation of biliary cells (Supporting Fig. S14).

Our study better delineates the pathogenesis of CCA by describing a novel function of JNK in cholangiocyte hyperproliferation. It also defines new therapeutic options to inhibit pathways involved in cholangiocarcinogenesis.

Supporting information

FigS1

FigS2

FigS3

FigS4

FigS5

FigS6

FigS7

FigS8

FigS9

FigS10

FigS11

FigS12

FigS13

FigS14

Supinfo

Supinfo

Supported by the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF), the SFB TRR 57, the CRC 1382, the DFG TR285‐10/1, the German Krebshilfe (Grant 70113000), the RTG 2375 Tumor‐Targeted Drug Delivery to CT. The START Program of the Faculty of Medicine, RWTH Aachen (#691405), the MINECO Retos (RyC‐2014‐13242 and SAF2016‐78711), EXOHEP‐CM (S2017/BMD‐3727), NanoLiver‐CM (Y2018/NMT‐4949), ERAB (Ref. EA 18/14) AMMF 2018/117, UCM‐25‐2019, COST Action (CA17112) to FJC, Gilead Research Award 2018. Grant PI16/01126 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) co‐financed by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) Una manera de hacer Europa, AECC 2017 Research Grant for Rare and Childhood tumors and Hepacare Project “la Caixa” to MAA. The SFB/TRR57/P04, SFB 1382‐403224013/A02, the DFG NE 2128/2‐1, MINECO Retos (RyC‐2015‐17438 and SAF2017‐87919R) to YAN. MRM is a recipient of full funded PhD scholarship provided by both German academic exchange service (DAAD) and the Egyptian ministry of higher education (MoHe) (GERLS‐German Egyptian Research Long‐Term scholarship Program).

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Contributor Information

Francisco Javier Cubero, Email: fcubero@ucm.es.

Christian Trautwein, Email: ctrautwein@ukaachen.de.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co‐first authorship.

- 1. Sirica AE, Nathanson MH, Gores GJ, Larusso NF. Pathobiology of biliary epithelia and cholangiocarcinoma: proceedings of the Henry M. and Lillian Stratton Basic Research Single‐Topic Conference. Hepatology 2008;48:2040‐2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thoolen B, Maronpot RR, Harada T, Nyska A, Rousseaux C, Nolte T, et al. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse hepatobiliary system. Toxicol Pathol 2010;38(Suppl.):5S‐81S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zabron A, Edwards RJ, Khan SA. The challenge of cholangiocarcinoma: dissecting the molecular mechanisms of an insidious cancer. Dis Model Mech 2013;6:281‐292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seki E, Brenner DA, Karin M. A liver full of JNK: signaling in regulation of cell function and disease pathogenesis, and clinical approaches. Gastroenterology 2012;143:307‐320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Girnius N, Edwards YJ, Garlick DS, Davis RJ. The cJUN NH2‐terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway promotes genome stability and prevents tumor initiation. Elife 2018;7:e36389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hubner A, Mulholland DJ, Standen CL, Karasarides M, Cavanagh‐Kyros J, Barrett T, et al. JNK and PTEN cooperatively control the development of invasive adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:12046‐12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu J, Wang T, Creighton CJ, Wu SP, Ray M, Janardhan KS, et al. JNK(1/2) represses Lkb(1)‐deficiency‐induced lung squamous cell carcinoma progression. Nat Commun 2019;10:2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davies CC, Harvey E, McMahon RF, Finegan KG, Connor F, Davis RJ, et al. Impaired JNK signaling cooperates with KrasG12D expression to accelerate pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2014;74:3344‐3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cellurale C, Sabio G, Kennedy NJ, Das M, Barlow M, Sandy P, et al. Requirement of c‐Jun NH(2)‐terminal kinase for Ras‐initiated tumor formation. Mol Cell Biol 2011;31:1565‐1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Das M, Garlick DS, Greiner DL, Davis RJ. The role of JNK in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dev 2011;25:634‐645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Han MS, Barrett T, Brehm MA, Davis RJ. Inflammation mediated by JNK in myeloid cells promotes the development of hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Rep 2016;15:19‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yuan D, Huang S, Berger E, Liu L, Gross N, Heinzmann F, et al. Kupffer cell‐derived Tnf triggers cholangiocellular tumorigenesis through JNK due to chronic mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS. Cancer Cell 2017;31:771‐789.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Das M, Jiang F, Sluss HK, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Flavell RA, et al. Suppression of p53‐dependent senescence by the JNK signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:15759‐15764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Das M, Sabio G, Jiang F, Rincon M, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Induction of hepatitis by JNK‐mediated expression of TNF‐alpha. Cell 2009;136:249‐260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cubero FJ, Zoubek ME, Hu W, Peng J, Zhao G, Nevzorova YA, et al. Combined activities of JNK1 and JNK2 in hepatocytes protect against toxic liver injury. Gastroenterology 2016;150:968‐981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zoubek ME, Woitok MM, Sydor S, Nelson LJ, Bechmann LP, Lucena MI, et al. Protective role of c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase‐2 (JNK2) in ibuprofen‐induced acute liver injury. J Pathol 2019;247:110‐122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cubero FJ, Singh A, Borkham‐Kamphorst E, Nevzorova YA, Al Masaoudi M, Haas U, et al. TNFR1 determines progression of chronic liver injury in the IKKgamma/Nemo genetic model. Cell Death Differ 2013;20:1580‐1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luedde T, Beraza N, Kotsikoris V, van Loo G, Nenci A, De Vos R, et al. Deletion of NEMO/IKKgamma in liver parenchymal cells causes steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2007;11:119‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cubero FJ, Zhao G, Nevzorova YA, Hatting M, Al Masaoudi M, Verdier J, et al. Haematopoietic cell‐derived Jnk1 is crucial for chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis in an experimental model of liver injury. J Hepatol 2015;62:140‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grasl‐Kraupp B, Ruttkay‐Nedecky B, Koudelka H, Bukowska K, Bursch W, Schulte‐Hermann R. In situ detection of fragmented DNA (TUNEL assay) fails to discriminate among apoptosis, necrosis, and autolytic cell death: a cautionary note. Hepatology 1995;21:1465‐1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cubero FJ, Peng J, Liao L, Su H, Zhao G, Zoubek ME, et al. Inactivation of caspase 8 in liver parenchymal cells confers protection against murine obstructive cholestasis. J Hepatol 2018;69:1326‐1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seehawer M, Heinzmann F, D'Artista L, Harbig J, Roux PF, Hoenicke L, et al. Necroptosis microenvironment directs lineage commitment in liver cancer. Nature 2018;562:69‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ehedego H, Boekschoten MV, Hu W, Doler C, Haybaeck J, Gabetaler N, et al. p21 ablation in liver enhances DNA damage, cholestasis, and carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2015;75:1144‐1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Willenbring H, Sharma AD, Vogel A, Lee AY, Rothfuss A, Wang Z, et al. Loss of p21 permits carcinogenesis from chronically damaged liver and kidney epithelial cells despite unchecked apoptosis. Cancer Cell 2008;14:59‐67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Affo S, Yu LX, Schwabe RF. The role of cancer‐associated fibroblasts and fibrosis in liver cancer. Annu Rev Pathol 2017;12:153‐186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Park SY, Roh SJ, Kim YN, Kim SZ, Park HS, Jang KY, et al. Expression of MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6 in cholangiocarcinoma: prognostic impact. Oncol Rep 2009;22:649‐657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mu X, Pradere JP, Affo S, Dapito DH, Friedman R, Lefkovitch JH, et al. Epithelial transforming growth factor‐beta signaling does not contribute to liver fibrosis but protects mice from cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2016;150:720‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Isomoto H, Mott JL, Kobayashi S, Werneburg NW, Bronk SF, Haan S, et al. Sustained IL‐6/STAT‐3 signaling in cholangiocarcinoma cells due to SOCS‐3 epigenetic silencing. Gastroenterology 2007;132:384‐396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smigiel JM, Parameswaran N, Jackson MW. Potent EMT and CSC phenotypes are induced by oncostatin‐M in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2017;15:478‐488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carpino G, Cardinale V, Folseraas T, Overi D, Floreani A, Franchitto A, et al. Hepatic stem/progenitor cell activation differs between primary sclerosing and primary biliary cholangitis. Am J Pathol 2018;188:627‐639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee MH, Koria P, Qu J, Andreadis ST. JNK phosphorylates beta‐catenin and regulates adherens junctions. FASEB J 2009;23:3874‐3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andersen JB. Molecular pathogenesis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2015;22:101‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Galdy S, Lamarca A, McNamara MG, Hubner RA, Cella CA, Fazio N, et al. HER2/HER3 pathway in biliary tract malignancies; systematic review and meta‐analysis: a potential therapeutic target? Cancer Metastasis Rev 2017;36:141‐157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nam AR, Kim JW, Cha Y, Ha H, Park JE, Bang JH, et al. Therapeutic implication of HER2 in advanced biliary tract cancer. Oncotarget 2016;7:58007‐58021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li L, Zhao GD, Shi Z, Qi LL, Zhou LY, Fu ZX. The Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway and its role in the occurrence and development of HCC. Oncol Lett 2016;12:3045‐3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chong DQ, Zhu AX. The landscape of targeted therapies for cholangiocarcinoma: current status and emerging targets. Oncotarget 2016;7:46750‐46767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baselga J. Targeting tyrosine kinases in cancer: the second wave. Science 2006;312:1175‐1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wood ER, Truesdale AT, McDonald OB, Yuan D, Hassell A, Dickerson SH, et al. A unique structure for epidermal growth factor receptor bound to GW572016 (Lapatinib): relationships among protein conformation, inhibitor off‐rate, and receptor activity in tumor cells. Cancer Res 2004;64:6652‐6659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Scaltriti M, Verma C, Guzman M, Jimenez J, Parra JL, Pedersen K, et al. Lapatinib, a HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, induces stabilization and accumulation of HER2 and potentiates trastuzumab‐dependent cell cytotoxicity. Oncogene 2009;28:803‐814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blechacz B, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma: advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Hepatology 2008;48:308‐321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guest RV, Boulter L, Dwyer BJ, Forbes SJ. Understanding liver regeneration to bring new insights to the mechanisms driving cholangiocarcinoma. NPJ Regen Med 2017;2:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Eferl R, Ricci R, Kenner L, Zenz R, David JP, Rath M, et al. Liver tumor development. c‐Jun antagonizes the proapoptotic activity of p53. Cell 2003;112:181‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hui L, Zatloukal K, Scheuch H, Stepniak E, Wagner EF. Proliferation of human HCC cells and chemically induced mouse liver cancers requires JNK1‐dependent p21 downregulation. J Clin Invest 2008;118:3943‐3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sakurai T, Maeda S, Chang L, Karin M. Loss of hepatic NF‐kappa B activity enhances chemical hepatocarcinogenesis through sustained c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase 1 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:10544‐10551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim Y, Kim MO, Shin JS, Park SH, Kim SB, Kim J, et al. Hedgehog signaling between cancer cells and hepatic stellate cells in promoting cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:2684‐2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mall AS, Tyler MG, Ho SB, Krige JE, Kahn D, Spearman W, et al. The expression of MUC mucin in cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol Res Pract 2010;206:805‐809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zender S, Nickeleit I, Wuestefeld T, Sorensen I, Dauch D, Bozko P, et al. A critical role for notch signaling in the formation of cholangiocellular carcinomas. Cancer Cell 2013;23:784‐795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kiguchi K, Carbajal S, Chan K, Beltran L, Ruffino L, Shen J, et al. Constitutive expression of ErbB‐2 in gallbladder epithelium results in development of adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2001;61:6971‐6976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lindsey S, Langhans SA. Epidermal growth factor signaling in transformed cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2015;314:1‐41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schneider MR, Yarden Y. The EGFR‐HER2 module: a stem cell approach to understanding a prime target and driver of solid tumors. Oncogene 2016;35:2949‐2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FigS1

FigS2

FigS3

FigS4

FigS5

FigS6

FigS7

FigS8

FigS9

FigS10

FigS11

FigS12

FigS13

FigS14

Supinfo

Supinfo

Data Availability Statement

Affymetrix Microarray was performed as described,( 17 ) and data were deposited with the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE140498.